Matthew Perpetua | May 28, 2025

Photo of Julia Gfrörer provided by the artist.

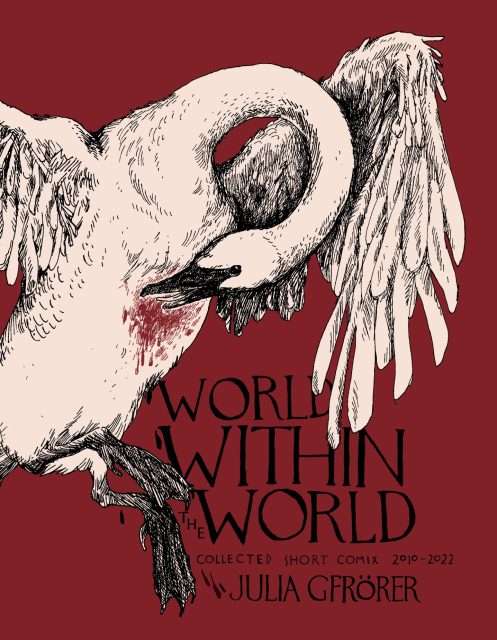

Photo of Julia Gfrörer provided by the artist.Julia Gfrörer has built an acclaimed body of work over the past decade and a half with a steady stream of self-published mini-comics and zines, as well as three graphic novels — Black Is the Color, Laid Waste, and Vision — that have been published by Fantagraphics. Gfrörer's stories frequently explore transgressive sexuality, horror, the occult, and religion throughout history, and are meticulously illustrated with her distinctively sharp and severe linework. Gfrörer's new book, World Within the World, is a collection of 39 short works that were originally published between 2010 and 2022.

In this conversation, Gfrörer discusses how she started in comics, her early artistic inspirations, the creative freedom of making zines, her personal rules for depicting extreme violence, and why some people have a hard time understanding comics as a form of serious literature.

MATTHEW PERPETUA: So where does comics begin for you, as a reader and as an artist?

JULIA GFRÖRER: I don't remember feeling any particular affinity towards comics as a kid. I was interested in a lot of different art forms. I was drawing comics, but I was also writing prose fiction, I wanted to sing and I wanted to act, and I took lessons in a few musical instruments and I learned to sew. My mother is very handy, so we were always making things at home. It just kind of came naturally to me that I would play with dolls and then I would decide they needed some kind of item and I would make it.

Making books came naturally out of that. And I read a lot. When I was real small, I had a subscription to Cricket Magazine, which was a literary magazine for children. They would have kind of a running commentary of comics along the bottom of the pages that was like different insects that would make comments on the stories and things like that, and explain to you what the words meant.

Were you drawing from young age?

Sure, but who doesn’t, though? Like, I see that in people's bios all the time. They say “I’ve been drawing since I could hold a pencil.” Like you and everybody, right? For some reason or other, that became the thing that I was identified as being good at, but I don't think I was actually good at it. But that was like, my thing. My best friend growing up wanted to be an author. So when we would work on stories together, I would draw them and she would write them. I believed that I was good at it before it was actually something that I was good at or trying to trying to do.

My earliest memories of drawing and creating like an emotion out of it. I would have these wild fantasies or I would see something in a book or on TV and I just wouldn't be able to stop thinking about it and I would have to draw it. And then I would have to hide the drawing because I was embarrassed of how intensely I felt about it. And in retrospect, that's a very similar impulse to what I do now when I'm looking for a story idea. I have to go after that simultaneous terror and attraction.

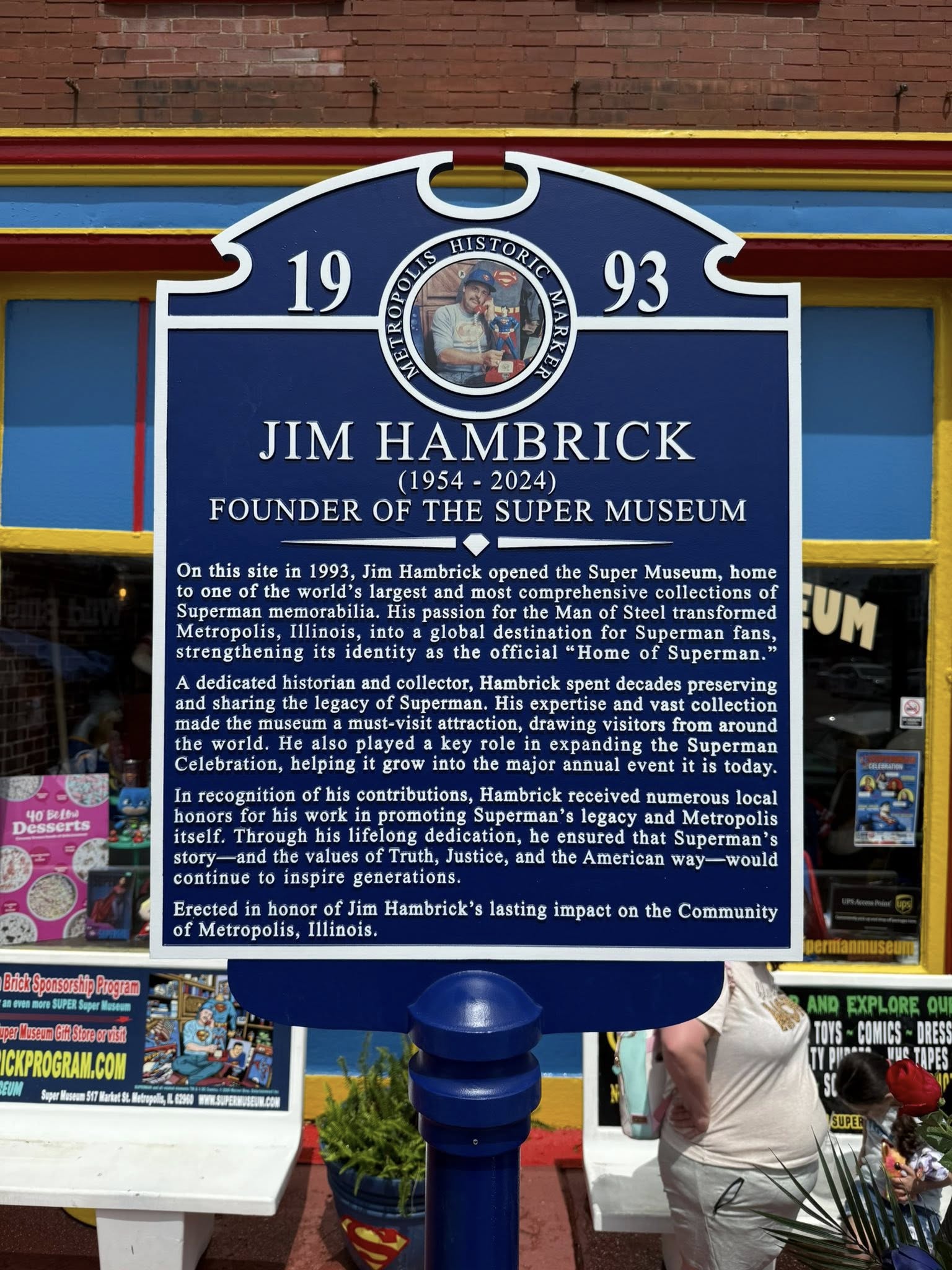

Cover to World Within the World.

Cover to World Within the World.Did you eventually become more exhibitionistic about it, as opposed to hiding it from your parents?

Yeah, when I was a teenager, I had a sketchbook with me all the time. This is when I was like maybe 14 or 15. All the drawings in it were really sad. I remember the few times that I let my friends look through it, because if you carry a sketchbook, people are like, “Oh, can I look at your drawings?” They would always be like, “geez, Julia, what the fuck?” It was a lot of drawings of me committing suicide in various ways or like, attempts to literally illustrate Smashing Pumpkins lyrics. But things that felt kind of illicit, is what I'm trying to get at. And then when I got to be a little older and start to have opinions about fine art, I realized that what I was drawn to was artists who were pursuing a similar feeling shamelessly. We're clearly chasing down things that were uncomfortable and embarrassing and just refusing to shut up about them.

Who are some good examples of that early on?

By the time I was 15, maybe 16, alternative had kind of given way to the pop explosion of the mid nineties. And likewise, I was moving away from what I could find on MTV or on the radio and towards indie music. So I was looking in zines or magazines, and not really on the internet so much yet. Except for Usenet. People would talk about stuff there and I would check that out. One of the things that I discovered that way was the Rachel’s album Music for Egon Schiele, and that was a very big deal for me.

Did that bring you to Schiele as well?

Yeah, absolutely. I really loved the pre-Raphaelites, and Maxfield Parrish, who is a local hero in New Hampshire, where I'm from. Art Nouveau, Golden Age illustration, that kind of thing because I read a lot of storybooks, including very old editions of books when I was small, because my mother is a collector of anything old and beautiful.

Edmund Dulac's illustrations for The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam were incredibly powerful to me, which is funny looking back on it because that and also Parrish are just young women in languorous poses with flowers and twilight gardens and things like that. But it excited my sense of romance and sensuality. And then coming to the Austrian expressionists like Schiele, who sort of naturally progress out of that Art Nouveau sensibility into something that is sensuous in a more confrontational and challenging way. That resonated with me as I became a little more emotionally mature.

Were you clocking a lot of technique at the time, or was it just the overall vibe and the subject matter?

Oh, not at all. I really had no idea how these things were made. At that point, I was so private about my drawing that I didn't know how to draw, and I wasn't asking either. But Schiele is very approachable, just with his mark making. It feels very spontaneous. It looks very like it's just charcoal, watercolor gouache. As opposed to something like Parrish, which has many, many layers of glazes on canvases with models and Schiele is just drawing himself in his room on a piece of paper with a piece of vine charcoal. I could understand how that was done. That began to feel more truthful to me, a more energetic and spontaneous expression.

How did your style as an artist emerge? Is your art at this time recognizable as your drawing now?

No, I don't think so. Let me rephrase that: I think that when you look at my work now, you can probably identify those early influences in it. I think Schiele is one of the artists that I've been compared to more, probably because his influence is more obvious because I draw a lot of skinny, miserable people in various states of tumescence. But if you look at the work that I was doing when I was a teenager, I had no idea how to even start to express myself that way. I didn't know how to draw. I wasn't really in conversation with a community of visual artists. I was like, inventing from scratch.

I was was reading comics a little bit, and I was getting into anime and manga. I was reading David Mack's Kabuki, which is funny now because it has kind of an Art Nouveau sensibility, also with the Orientalism. There's something very self-indulgent and very lush about it. But I wasn't really trying to replicate that.

At what point does your art start looking like you, like your hands are doing what you want them to?

I wasn't really drawing comics as part of my regular artistic practice until maybe when I was around 25. When I moved to Portland, basically. Before that, I drew a few comics in college. They had a class you could take as an elective about making comics, and I was like, yeah, I'm kind of interested in that. I had done little comics like the ones in Crooked Magazine to illustrate zines that my friends and I had made in in high school and and junior high, but I wasn't thinking of that as my core work. I went to college at a time when comics was not really something that you could study at art school. I remember my teachers being nonplussed like by the fact that I wanted to make representational work, and that I wanted to make work that conveyed a narrative.

I was really interested in poetry and medieval literature, and I did a bunch of paintings based on medieval hagiographies or the King Arthur stories, “The Knight of the Cart” and things like that. My advisors and my professors would come around and be like, “Okay, what is this?” And then I would have to give them like a 10-minute-long explanation and they couldn't understand why I would be doing that. And I'd be like, you know when John William Waterhouse does a painting of a lady and he tells you it's it's Circe, then you have to know who that is? Like, is it crazy for me to think that people are going to know? Is it crazy for me to expect that people would know these things that I'm writing for? Maybe it was unrealistic of me, but yeah, I remember them saying, “Don't you want to do something less ephemeral?”

What did they mean by that? Like, why aren't you making something like a fine art painting?

Yeah, I think that was the idea. Which is funny in a way because drawings, prints, and even paintings like I was doing then, there's only one of them and you could do hundreds in your lifetime and only a couple will be really remembered, if any. But when you do a book, you put hundreds of copies of it out into the world, or thousands. Like scores and scores of people read your story, share it with their friends, carry it with them. And it turns out to be much less ephemeral than a standalone image.

My work has really found its way into people's lives. That was something that surprised me about my first serious comic, which was Flesh and Bone, that I made for Dylan Williams of Sparkplug Comics in Portland. That's the first comic that I did that resembles the body of work that I have now and it's the earliest comic in World Within the World.

How did your style as a writer emerge? Was it separate from or in tandem with your visual art?

By the time I got to be in high school, I wasn't really writing prose for fun anymore, like I did when I was a kid, and I sort of never really did again, other than the rare fanfic. So I don't have a sense of myself as a writer, except in nonfiction. I had a column in The Comics Journal for a little bit, writing comics reviews or writing essays and writing things for the school newspaper. My sense of my own voice as a prose writer is that it’s really unpleasant. It's pedantic, it's convoluted. I mean, I can't help it. It's like, you've seen my tweets, but my prose is worse.

Why do you think you're very different in how you write for comics? Do you think of what you do in comics as writing?

Oh yeah, absolutely, I do. And I think that the illustration is part of the writing. They're not separate to me. A lot of people who don't read comics don't quite recognize this, that reading a comic is different from reading a picture book. There's not like a description of a thing and then a picture of a thing. You have to read the pictures in a series and you need to see each of them in order in the same way that you need to see each word in a sentence in order in order to follow along and glean a meaning from it. And the process of creating that visual sentence, I think that's a type of writing. It's distinct from prose writing, but it is a process of organizing your thoughts into a communicable form, into symbols that can be then shown to somebody else who will then get the information from the symbols. And you know, there's dialogue, but that's that's just one tiny part of it. My comics don't even have that much dialogue most of the time.

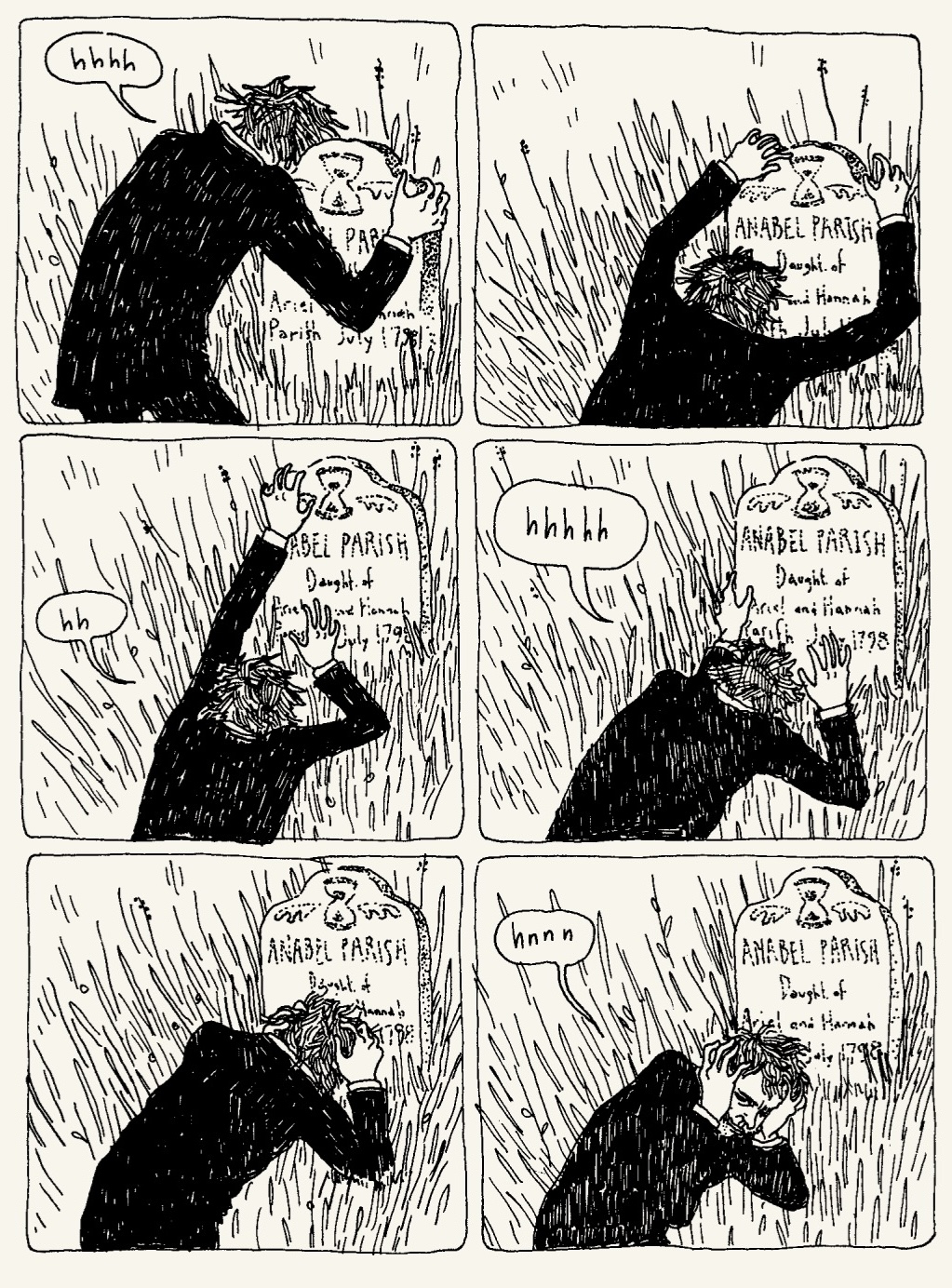

A six-panel page from "Flesh and Bone."

A six-panel page from "Flesh and Bone."Your comics are often fairly dense with panels. Is it equivalent to having very long sentences or a long paragraph? It can also be percussive, in musical terms.

You know, Flesh and Bone had six panels per page and my next long comic after that was Black is the Color, which also had six panels per page because that was the longest thing that I had ever committed to doing. And I knew that I could handle six panels per page. So I stuck with that. But my next book after that is only four panels per page, which is very few. I don't I don't know that I've ever seen a serious graphic novel that has only four panels per page. Have you?

Yeah, I'm sure. It’s funny, I don't always look at comics pages thinking about the the the density of panels. I’ve read interviews with comics artists who do work for hire who say they prefer fewer panels per page, that four or five per page is a good comfort zone. But it’s like, what’s the story? It depends on what you’re showing.

Yeah, you move through the page differently. I think the common wisdom on the subject is that more panels means that you're moving through the page more quickly, um which, you know, it it sort of looks at the page as like musical notation, where you have a certain rhythm to it and the page size is one and the panels, the number of panels is another. So, you know, with smaller panels, you've got 16th notes or something like that. But it's not necessarily the case, that you read a page more quickly when there are fewer panels or that you spend less time with each panel. I don’t think the amount of time that a reader spends with each page is consistent. It depends on the pace of the story and stuff.

A comic that I think about all the time is Cryptic Wit by Gerald Jablonski. That’s the densest comic that I have ever experienced, and it provokes a huge amount of anxiety when you look at the page. Reading one page of that book takes like an hour. So it's really the level of detail in the image that dictates how quickly you move through it. And a larger illustration tends to have more detail.

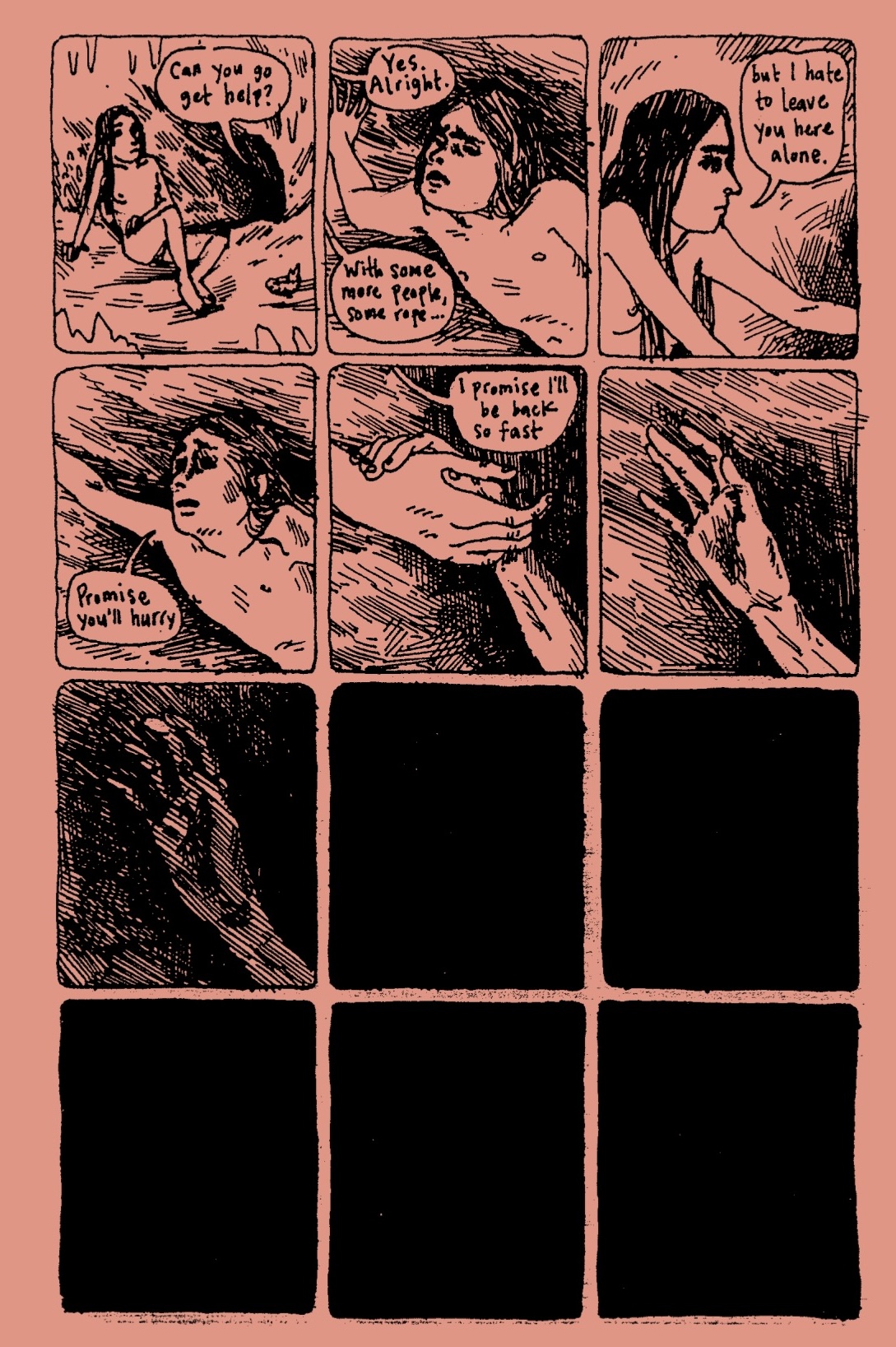

A page from "Forgiveness."

A page from "Forgiveness."You have one comic in World Within the World, “Forgiveness,” from 2013. And that one has, I think, something like 30 panels per page, and it’s four or five pages. Were you stunting there? That is kind of an absurd number of panels for a page.

It is. Well, that that was originally printed in Arthur magazine, which is a tabloid size newspaper style magazine. I was given a page at some absurd dimensions. I feel most comfortable drawing pretty small and with a very fine line. Nearly all of my comics are drawn with the same rapidograph, which is a 0.35 millimeters size nib. So I was immediately like, how am I going to fill up all this space? And the way that I decided to do it was by putting two stories side by side that ran concurrently. And so each of them was only the width of half the page. It was not a flex so much as just like a way for me to break up the space and not feel too intimidated by it. I don't think that those panels are actually that small. They might be, they're probably about one and a half inches square in the original.

I also sometimes I have to make the panel small so that I don't spend too much time on them. Because when you do have a lot of room, you can get kind of anxious about all the space and you start to fill it up with marks that just create noise and distraction and confusion. Making the panel smaller is one way to make it impossible to get caught up in the details.

What is your relationship with working in color? One of the things that's striking in this book is there's some pieces that will have monochromatic spot color, and then there's a lot of comics that are presented on different color paper, which I don't think I've actually seen in a collection like this before. How did you arrive at those ideas?

I don't really like to use color. I guess that's obvious. Some of the pieces in the book actually do have a color version that I probably did because the art director insisted and it's not included here because I don't like it as much as I like the black and white. Adding color to a comic is incredibly time consuming. And for me, it doesn't pull its weight. Usually it doesn't add enough information for me to double or quadruple the amount of time that I spend on a page that to me is complete once I finish the black and white ink.

I don't think that just because we can have color that we must. I think a lot of things are more interesting to look at when they're in black and white. And the drawing is more or less realism, but they're not really illusionistic, so I don't think that there is a need for me to try and create like a deeper illusion of, like, a photographic reality. We all know it's a drawing. So it's not where I choose to put my energy. I will also point out that the artists that are most influential to me, Schiele used some color, but not a lot. Tony Millionaire, Dame Darcy, and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell – I think those are the biggest influences from comics on the way that I draw. I think you can definitely see those styles in my work and none of those use color very much at all.

Do you know, the photographer Sally Mann?

Yeah, of course.

She's an artist that is one of my favorites. And again, you know, it's not that the work is entirely unfiltered because it certainly is, there are certain manipulations. But there is a confrontational nature to it. I think that you would lose that if the work was not black and white. She uses a very large format, silver nitrate. The medium has a beauty of its own, which is distinct from the reality that's being captured. You know what I mean? The content is just one part of it. And I kind of resent that color is the the default.

There are so many modern comics where the color just kind of stomps on the linework.

Right? I love the line.

The line, to me, is the most exciting part. You're seeing the work of hands. My two biggest obsessions are music and drawing, and both are ultimately about how people use their hands and bodies. You're getting something communicated with a body. Even in music that's programmed, like a drum machine, you can feel the hands of the artist.

Yeah, the artist's hand is essential. The reason that we are making art is to communicate with one another. The farce of AI-created quote unquote art is that nobody wants to hear something that is not from another person. That's the whole reason that we're doing this. It's so powerful when you see those little bits of humanity. What's the Sumerian copper merchant, Ea-nāṣir? This was a meme. Like, an angry letter that somebody wrote to a guy who had sold him some copper that turned out to be not the quality that he had hoped for. It's really just a letter to the manager, but the indignance speaks to you across the millennia. Things like that, these human moments, these little fingerprints that make us look at somebody else and say, oh, that's me. That’s so exciting.

Page from "Palm Ash."

Page from "Palm Ash."So, with the monochrome color pages, was that a decision to visually break up the stories in the anthology?

Yeah. One of the other reasons that I arrived at the style that I did in my work is that I am kind of a zine evangelist. I believe in self-publishing very strongly and even when I have had professional publishers to work with, I have always done self-publishing alongside it. Photocopying is significantly less expensive when it's black and white, and clear, dark black lines on white photocopy very well. It's a style that is designed to be easily reproduced. And then, in order to make the books a little more exciting to look at and easier to tell apart, I started copying them onto different colors of paper, which are usually available very inexpensively when you take your work to a copy shop. You can find partially used reams of paper at thrift stores often, or you can steal them from work. They're just easy to get and an easy way to make the zine more beautiful, basically for free.

And so I fell into a pattern of doing my zines like that where it would have the black and white line art. It would have a wraparound cover. A lot of these are decisions that I made partly just to relieve my future self the burden of making these decisions. They just all look like they’re of a piece so that I don't have to think about designing an entirely new aesthetic for each one. My zine, or mini comic, which is in the collection called “Palm Ash” was printed on an acid green colored paper. It might be gamma green. I did that because I was really obsessed with chartreuse at the time, like a bright, bright acid green. You can also see it in my comic “Phosphorus,” which has little spot colors in chartreuse. One of the two colors in “Forgiveness,” which I made around the same time, is like a acid yellow green.

Anyway, I printed “Palm Ash” on this kind of eye-watering paper that I just fell in love with, and then it was printed in Best American Comics that year. And whenever I would show it to somebody, you could pick it out easily because it was all white pages and then this strip of acid green. So I found that charming. And I was like, well, I could do that with all my comics. If I put them in a collection, each of them would be a different color. I thought that idea was really exciting and it does look beautiful.

I don't think I’ve ever seen anyone do this before, so it really does pop.

Well, in 10 years, everybody will be doing it.

Does the zine format take pressure off of you? To make something smaller, something that doesn’t have to be an enormous number of pages?

I think zines are a part of my most formative ideas about what art is. As I get older, I look back more and more on my early experiences and realize, you know, although that was zines, that was self-publishing.

My parents had a Quaker wedding and I grew up going to Quaker meeting and we would often sing. At every Quaker meeting, the children would sing because it's hard for children to sit through an hour long meeting for worship. And the books that we had with the lyrics of the songs that we would sing were handmade by the children of the meeting of the generation before who were now adults. Each one had a different hand drawn cover. They had each drawn little illustrations to go along with the photocopied lyrics and the bindings were hand stitched, which is so charming.

I also used to see the Bread and Puppet Theater, which is a radical puppet theater that originated in Greenwich Village, but by the late ‘70s had moved to a farm in Glover, Vermont, where as far as I know, they exist to this day. The philosophy behind Bread and Puppet is very low barrier to entry. The puppets and the props, they're deliberately very handmade looking, very rough. There's a lot of brown paper, cardboard, woodcut prints and handmade things. When you would see them perform they would often have their own little books available that they had made which, again, were zines.

I don't think I grew up with the idea that people need permission from some authority to make art. I feel like a lot of people have that now. Well, I know that they do because on Zine Crisis, my Discord server, they talk to me about it all the time. They say, “I don't know if I'm allowed to make this.” Like, well, who will stop you? If you self-publish, then you can do whatever the hell you want. And nobody can really do anything about it. It's the way that radical ideas get out into the world. Even an ISP can be a form of oversight, and I just don't think that things like that have a place in art. So I'm always kind of compulsively making things, which again, is kind of how I grew up.

Is this part of what has made you gravitate towards transgressive work? If you're doing it yourself and no one can say “you can't do this,” so you may as well go all the way?

I think maybe it goes in the opposite direction, that I have stayed kind of attached to these less mainstream publishing methods because I am not really fit for decent company. I don't think that I could make like a nice book if I wanted to, and I can't imagine wanting to.

What are you picturing when you say “a nice book”?

I don't know. I'm scared of saying something that exists and offending somebody.

Yeah. But not like overtly sexual, not overtly horrific?

Well, I don't know, like a flat color young adult story about sports.

Slice of life, basically.

Even if I if I wanted to, like, “Oh, I need this $40,000 advance, I've got to make the Babysitter's Club graphic novel.” I can't. I couldn't. I can't.

This body of work covers a bit over a decade of your work. What do you feel are the most important changes you've observed in yourself as an artist over the course of that time?

It's not the kind of thing that I like to reflect on. I don't like to think of myself changing. I like to think I got it right and I continue to get it right, from the beginning.

It does look very consistent. You could lie and say you just did this all in the past two years and people would believe you.

The comics in the book are deliberately not laid out in the order that I drew them, but they are roughly in the order that they take place, in their respective time period. Other than the very first comic, which is kind of outside of time and represents sort of a thesis statement for the work as a whole. The first comic in it takes place around like maybe 40 or 50,000 BC, and the last comic in it takes place in maybe like 2050, something like that, the near future.

I'm sure that if I had put them in the order in which they were made, there would be a probably a more gradual change in the way that I draw, but it probably would just consist of little tricks of illustration that I've learned over time. Probably the backgrounds are more distinct from the foregrounds, that kind of thing.

When I make a longer work, by which I mean anything over like two pages, really, I always draw it out of order. I will never draw a comic starting on page one. And that's one of many tricks in my arsenal to overcome my natural reluctance to put my thoughts and feelings down on paper for other people to see. I think that's a natural fear that people have that I have. So I always start with whatever looks like the most fun for me to draw, which is usually, you know, animals, hands, faces, drapery, maybe.

It’s funny, that’s a lot of things a lot of artists say they hate drawing, especially hands.

I know. I love hands. They're the greatest, so expressive.

Anyway, I start out by doing the pages that I'm most excited to draw and then by the time that I've drawn on all all of those, then it's like mostly done I'm like, well, I might as well do the rest. So it's partly motivational, but also part of the reason that I do it that way is because I'm trying to avoid that thing where your drawing style kind of gradually shifts and you can see it from the beginning to the end of the comic.

Your drawing style also changes naturally from day to day depending what mood you're in, and the weather can affect the flow of the ink. So the variations that come with experience, it's fine for them to be there, they can just be like another type of variation from page to page and become less obvious so that they don't seem like they're part of the narrative.

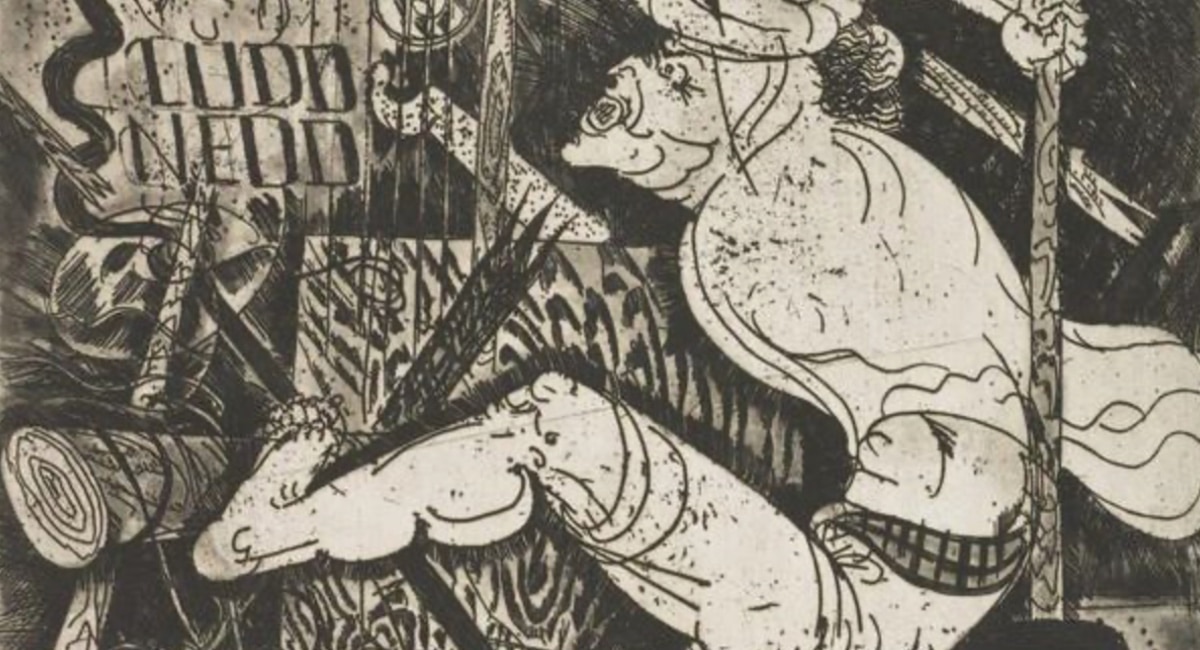

Sequence from "Too Dark to See."

Sequence from "Too Dark to See."Are there any self-imposed taboos in your work, like rules that you won't break?

Yes, there definitely are. Probably a lot of them are not things that I'm immediately conscious of. I won't put a beautiful girl on the cover of my book, just because I find it boring and kind of pandering, and also obviously kind of misogynist. I guess I don't really like to put people on the covers of my books at all.

I'm very careful about the way that I depict violence, domestic violence, sexual violence, things like that. I think it's important to show, and I won't hide them. There can be a tendency to think it's fine to show these things as long as you do it properly in a way that it telegraphs your true intentions, so you have to have a disclaimer on every page that says, well, this character is stomping on a duckling, but I would never stomp on a duckling.

I try to show things like that with as little judgment as possible, because when you encounter those things in real life, they don't usually come with a disclaimer. And usually when violence suddenly appears in your otherwise violence-free day-to-day life, it is difficult to know how you are supposed to feel about it. So I don't want to give the reader any help in that regard.

I also won't show things that I can't stomach. So if there's a certain type of violence that I show, like, for example, I don't know if I've ever shown somebody being burned alive. I think probably not. But if I were to show that, I would do my best to read firsthand accounts of that type of death, people who have come close to it, people have witnessed it, or maybe even watch videos of it if they exist. I mean, to my way of thinking, it's the least that I can do.

Like, to honor those who have been burned alive.

I guess it sounds kind of silly when you put it that way. I just don't think that I have any right to use that as part of my story if I can't face it. Does that make sense?

Well, you're taking a lot of time to draw it, so that's a sustained amount of time where you have to think about it.

Yeah, and that's part of how I choose the things that I write about. I will purposely choose things that are difficult for me to think about. I really hate drawing close-ups of people screaming. I hate to look at them, but I do sometimes think they're necessary. So I and make myself do it and I lean into the discomfort for my own sake to feel like I've earned it, maybe. It makes my entire process sound very masochistic. It's like the comic is just a byproduct of my own need to just kind of swim around in the cesspit of human experience. That can't be healthy.

And yet.

And yet. I mean, it’s more healthy than a lot of other ways that I could be chasing that feeling.

When do you feel surprised by your own work?

I don't know. Do I feel surprised by it?

I suppose that could be as small as a page turning out differently than you thought it might.

Sometimes, not always, but often the way that I draw something in pen, very small variations in the line can make a big difference, especially when you're drawing somebody's face. So sometimes something unintentional can happen that feels more right than the way that I'd planned it. Like the character, they turn out looking more surprised than angry. I'm not one of those writers who believes that their characters have independent life and dictate their stories themselves, but sometimes little quirks of chance and little muscular spasms in my drawing hand can create something kind of unexpected.

Like I said, I'm always writing things that I think will be engaging for me to draw. But sometimes something that I think is going to be not that interesting to draw, but feels necessary, will turn out to be pretty thrilling. Something like a landscape that I'm just like, well, there needs to be an establishing shot here, I suppose. And then I get really into the way that I'm rendering the trees or something and the landscape begins to have a personality and kind of asserts its importance on the page.

Do you feel like you ever have ideas that are beyond your capabilities as a draftsman?

Oh, for sure. I don't know about as a draftsman, but I do have ideas that I don't feel equipped to bring to fruition. Sometimes I write a story and then I feel like it is so miserable that I can't commit to spending enough time with it to make it into a finished thing.

I think I can draw anything that I'd want to draw. And if I don't know how, then I will learn. I have all of the necessary faculties, both mental and physical, to execute a lifelike drawing of anything. Or at least a convincing drawing of anything that I want to, but there is the question of whether or not the ideas that I have are worth the contemplation.

I wrote a comic many years ago now that it was maybe 30 or 40 pages long. At least half of it is a rape scene, and the woman is very badly burned during this process. And then the rest of it is her trying to get to safety with these extensive injuries that she then has. I really like the story. It means a lot to me but I don't want to draw it. I just don't want to.

Do story ideas tend to simmer for a while or do you more often draw them shortly after you come up with the plot?

Kind of both. Sometimes I'll have maybe one or two images for a story that stay with me for a long time, and then later something else will appear to connect to it. And then it suddenly makes sense. I compare it to like if you have like a chair that you really like, and then you have to be like, okay, now I have to find like a rug that goes with this chair, and maybe an end table that would fit where I want the chair to go. I have to find all this different stuff that is going to support the chair's existence or the chair's presence in your living space.

For example, in my book Vision, the central image is this woman who is having an affair with a a ghost that lives in her mirror on her vanity in her bedroom. I guess it's not really clear what kind of supernatural entity it is, but I think it's a ghost. Then a lot of the story comes from that, from like, what kind of person would you have to be in order to fall in love with a ghost that lives in a mirror? How would that make you feel? And also, what would you have had to experience beforehand in order to make you susceptible to this kind of bizarre circumstance? And then as I'm building that, other things appear or rise to the surface of this bog of my subconscious.

I saw a picture, probably on Tumblr, of a tool called a fleam, which is a type of lancet, which is a type of scalpel that is used for making a nick in a person's veins in order to bleed them therapeutically. And this particular fleam that I saw had a spring mechanism and multiple blades, maybe four or five blades. Like the Gillette of the future. So you just press the one button and it goes flick and creates several wounds for bloodletting all at once. I found that so captivating. And then I was like, the ghost story could have that fleam in it. So these things kind of expand from there.

Anyway, I'm constantly looking for new things to experience, new stories, new images, new ideas. You never run out of them, right?

Sequence from "Dark Age."

Sequence from "Dark Age."When you're working, how much do you think about the reader, or your audience in general?

Almost not at all. I really am just trying to indulge my own interests and passions. Because how can I know what effect these things will have on other people? There's no way to predict, right? Every day I try to anticipate somebody else's needs and get it wrong at least once. So other than the more mechanical concerns of like, if I say Gregor was here on page 20, then do I need to mention Gregor on page 2 so that it's not completely distracting or confusing?

The first comic in World Within the World, which is "Dark Age," has a pretty good sized section that is this young man and woman are are exploring a cave and the young man gets stuck. So the woman has to go for help, which means that she brings their one lamp with her and he's stuck. He's left there in the dark and the viewer stay with him. So then there's several pages that are just with the same structure of panels, the same rhythm, except they're all black. I did this with the sense that this would create some anxiety in the reader, understanding that that the person reading this story would not know whether or not this darkness would end.

I'm sensitive to the things that a reader might be ignorant about that I can either add or remove information to create the effect that I want in the story, but I would never even dare to try to make something that is appealing to anybody but me. I wouldn't know how.

I think that I got very lucky in that the kinds of things that get me excited have gotten other people excited. That was just luck.

What do you think is the most widely held misconception about comics, or specifically non-mainstream comics, like your part of the field?

My experience has been that when I talk to people who are not comics people about the work that I do, I have to find my way through a series of assumptions that they might have about it. So when you say comics, most people think of superheroes. So i have to say no, not that. And then they think, oh, for children. So I say no, not that. And then you bring them to from that point, to “oh, like Maus.” Most people who read have heard of Maus. And from there, they can conceive of comics about things that happened, documentary or memoir, or journalism in a comics medium.

I think that serious fiction in comics is a little harder for the average literary fiction reader to grasp. And I think that the reason for that, is that as lovers of books, intellectuals kind of fetishize the words, and having a large vocabulary and being able to parse a complicated sentence. These are necessary and important skills for literature in an academic sense, in the way that we are exposed to them in high school and college. So there's a misconception that reading pictures is subliterate, that pictures are the recourse of people who cannot express themselves in words.

It could also be vice-versa.

True.

We do learn to parse images in the same way that we learn to parse speech. If you don't develop that part of your brain when you're basically an infant, you can't do it later in life. You can't look at a picture of something and understand that it's something. So I think that the intellectual rigor required to glean meaning from a comic or a story told with images, people who haven't really bought into the medium as a whole and accepted the entire lifestyle have, I think, a pretty limited understanding of what that is.

There's the perennial joke among cartoonists about whether or not comics are serious literature. We joke about it because, I mean, it's true, right? If you see any mainstream coverage of comics as often as not, it's “comics are not for kids anymore.” There's this kind of incredulity. You and I, Matthew, know that comics have been not for kids since ... for longer than they have been for kids.

Certainly longer than either us has been alive.

Sure. A lot longer. And the primacy of verbal communication, I think it's artificial. I think that communication through images is easily at least as complex, but maybe requires less formal education and maybe for that reason it is denigrated. That's what I think is the biggest misconception that people have about comics is, that they're not serious literature, which they are.

A lot of your work is so dense with references to history and religion and mysticism. It’s all these things that if you were doing it in prose, you would be spelling out a lot of these things out. But you're throwing people in the middle of the ocean most of the time.

I'm taking for granted that they will know a lot of the things that I'm referring to, or else they'll figure it out on the way. As much as I dismiss my own abilities as a prose writer, if that was where I had chosen to focus my attention, I don't know if I would have had a career as a literary fiction writer fiction. But I think that I would have been able to do it with equal skill, and you know, I could spell all these things out if I wanted to but i don't want to. I want the reader to have to meet me there, I just think that's more exciting. It's more fun for both of us.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·