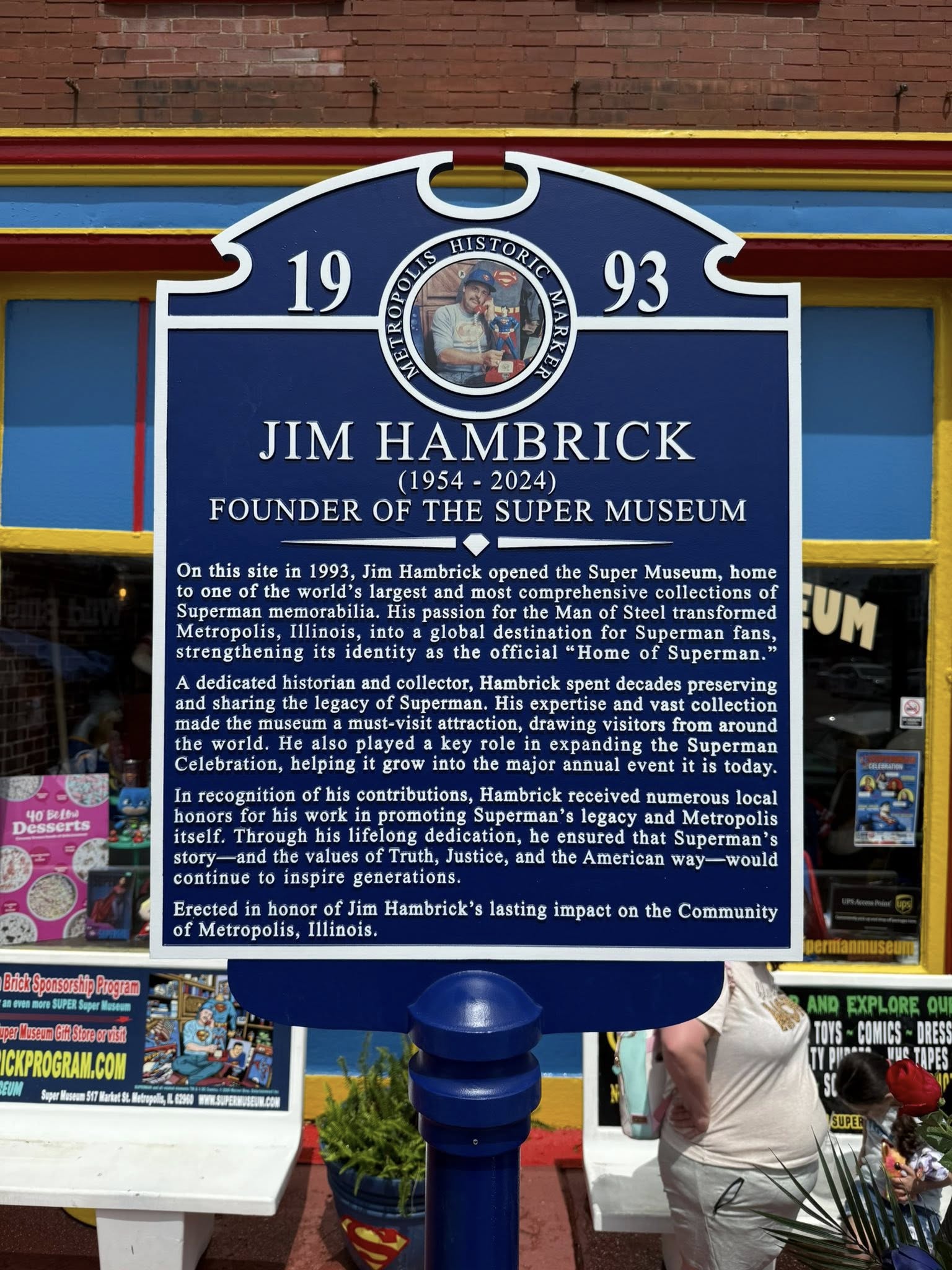

Robert Aman | June 11, 2025

Jean-Louis Gauthey at the Cornélius office.

Jean-Louis Gauthey at the Cornélius office.The story of one of France’s most influential publishing houses was almost over before it had even begun. Founder Jean-Louis Gauthey had started on a small scale. Barely 20 years old, he founded Cornélius in 1991 while helping out at a small printing house in Pigalle, one of Paris’s more notorious entertainment districts. The first product to bear the Cornélius name was a screen-printed and varnished cardboard puppet featuring Robert Crumb characters. Gauthey brought them to the festival in Angoulême hoping to earn a buck, but the sales were a failure. The discerning Angoulême audience considered the price tag far too high.

Gauthey responded by aiming even higher—this time by publishing Crumb’s chapbook Harlem in French, released in January 1993. The book collected Harlem and Bulgaria, two pictorial place-essays Crumb created in the mid-1960s for Harvey Kurtzman’s Help magazine. The publication featured twenty-eight pages of silkscreen illustrations, including one-fold-out page that doubled in size, along with a one-page hand-lettered introduction by Crumb. A first glimpse of what would define Cornélius’ signature style emerged: silkscreen prints—particularly on covers—and a meticulous dedication to the book as an art object. However, the print quality of Harlem fell far short of Gauthey’s expectations due to the poor-quality copies of Crumb’s pages he had to work with. Unwilling to compromise, he chose to destroy the entire print run, nearly bankrupting the newly founded company in the process.

These are just a few of the many mishaps recounted in Cornélius ou l’art de la mouscaille et du pinaillage (2007), a book in which Gauthey reflects on the first 16 years of Cornélius. Rather than being filled with self-congratulatory anecdotes, the book focuses on the various challenges the publishing house has faced—a conscious choice, according to Gauthey, who explains that it was intended as a slightly satirical work, spotlighting the less flattering aspects of the company’s history. At the same time, the ability to take such a lighthearted approach is a privilege reserved for a publisher that knows that his company stands on a solid foundation of success. After all, Cornélius is widely considered as a bastion of independent comics in France. Alongside other influential alternative publishers such as L’Association, Ego comme X, and Amok, Cornélius was a key player in the ”new comics” movement of the 1990s that revitalized French comics culture. Together, these publishers challenged the dominance of commercial storytelling in the mainstream industry and transformed bande dessinée into a fertile ground for artistic expression.

In 1993, Gauthey began publishing comics by Jean-Christophe Menu, Lewis Trondheim, and David B.—all founding members of L’Association—with silkscreened covers and photocopied interiors. The connection between Cornélius and L’Association remained strong for years. Not only did several artists publish with both houses, but Menu also described Cornélius as L’Association’s closest ally in Plates-bandes (2005), his polemical manifesto that sought to distinguish alternative publishing from the mainstream. Moreover, under his pseudonym Jean-Louis Capron, Gauthey collaborated on comics with Patrice Killoffer, another one of L’Association’s co-founders, while also publishing his own work in edited collections released by L’Association. However, in contrast to L’Association—which has been the focus of numerous books and academic studies— little has been written about Cornélius, even in French.

Nevertheless, Cornélius has made its mark in its own right. In the 1990s, alongside the previously mentioned works of Menu, Trondheim, and David B, the publishing house helped launch the careers of Blutch, Pierre La Police, Joann Sfar, and other notable names on the French comics scene. Soon after, Gauthey began expanding Cornélius’ catalog of international cartoonists in two geographical directions: West and East. The publisher added works by Daniel Clowes, Chester Brown, and Charles Burns to its growing roster of North American artists. Notably, Cornélius has become Burns’ primary publisher—so much so that his latest book, Final Cut, was released in French before it became available to English-speaking audiences.

For many French readers, however, Cornélius has also served as a gateway to Japanese comics. Since the early 2000s, the publishing house has introduced some of the most revered gekiga artists, including Yoshihiro Tatsumi, Shigeru Mizuki, and Yoshiharu Tsuge—many of whom are familiar to English-speaking audiences thanks to Drawn & Quarterly. Mizuki even won the prestigious Fauve d’Or for Best Book at Angoulême in 2007 for NonNonBa.

Cornélius continues to blend past and present, reprinting alternative comics from the 1970s—such as the works of Nicole Claveloux in newly restored hardcover editions—while also championing contemporary artists, primarily from the French comics scene. Among its notable authors are Antoine Cossé and Jérôme Dubois, the latter of whom was shortlisted for Best Book at this year’s Angoulême festival with his latest work, Immatériel.

Cornélius office located in a warehouse on the right bank of the Garonne River in Bordeaux.

Cornélius office located in a warehouse on the right bank of the Garonne River in Bordeaux.In 2014, the publishing house relocated from Paris to Bordeaux, in southwestern France, to escape what one employee described as the “pollution, cramped conditions, and high costs of Paris.” Its headquarters is now based in Fabrique Pola, a former warehouse transformed into a creative hub for companies dedicated to the visual arts. The building sits along the Garonne, the wide river that divides the city in two, but on the right bank, where streets filled with trucks and construction sites dominate the landscape—in stark contrast to the postcard-perfect, picturesque 18th-century city center on the opposite shore.

Gauthey opens the door. He wears slim-fit jeans, a red sweater, and black boots. His voice is soft, almost quiet. His demeanor is kind yet slightly reserved, his gaze focused. He takes frequent puffs from his vape—so often, in fact, that he could rival Art Spiegelman as the comics scene’s foremost nicotine addict.

After a brief tour of the office—two rooms filled with books, including a large shelf that houses parts of Gauthey’s private library—we sit down at the table to discuss, among other things, the history of the company, disastrous financial decisions, and what he looks for in a cartoonist. But also, his upbringing, his relationship with L’Association, and how he made headlines after a contentious dispute with the publishing house Delcourt over the rights to Daniel Clowes’ works.

— Robert Aman

ROBERT AMAN: You’ve spent more than half of your life publishing comics. What first drew you to becoming a publisher?

JEAN-LOUIS GAUTHEY: My journey toward publishing started when I was a kid, probably around six or seven years old. I wanted to create my own fanzine, even though I had no idea what a fanzine was at the time. So, I made one, and my father printed copies using the office Xerox machine. I put together one or two issues, incorporating some of my own drawings, but most of it consisted of photocopied pages from Mickey Mouse and other Disney comics.

So, you re-drew your favorite Disney stories?

No, I was far too lazy to redraw anything. I just cut out a few stories from magazines and pasted them into my own fanzine. Later, when I was around 18 or 19, I realized that a regular 9-to-5 job wasn’t for me. After finishing high school, I moved out on my own. My parents helped me rent a small apartment in Paris, but to cover my expenses, I had to take a series of really lousy jobs. Those experiences made me determined to find a career that offered me as much freedom as possible. I knew I couldn’t work under a boss constantly telling me what to do. I started working in a bookstore, then moved on to a book distributor. Eventually, I became an apprentice at a small silkscreen printing company in Pigalle. It was during that apprenticeship that I decided to launch Cornélius. I borrowed money from people I had met through my apprenticeship to get started.

Before we discuss the early days of Cornélius, I’d like to learn more about your background. When and where were you born?

I was born in 1969 and grew up in the outskirts of Paris. The area was split into two parts—one wealthy, one poor—and I lived right in between them.

So, in more ways than one, you were middle class?

Yes, lower middle class.

What did your parents do for a living?

My mother was a high school teacher, and my father worked for the French national electricity company.

How was your experience in school?

School was tough. My junior high school was rough and violent—there were constant fights, drugs, even prostitution. I was bullied and attacked daily. When I went to high school in a wealthier part of the city, I faced a different kind of hostility. To those students, I was the poor, miserable kid. On top of that, I was physically small, which didn’t help. All of these experiences shaped my personality. I always felt caught between social classes. At first, I reacted to the abuse by rebelling and acting out, which is one reason my parents agreed to let me move to Paris and start living independently.

What kind of comics did you read growing up?

My favorite was Lucky Luke by Morris and René Goscinny. I still admire and read it today. Back then, though, I didn’t have a specific taste—I read anything I could get my hands on. I loved Pif [a magazine published by the French Communist Party] which featured great artists like Hugo Pratt and Gotlib. Gotlib’s work had a huge influence on me. I would read whatever comics I found at friends’ houses, but I never liked Tintin. It made me anxious for some reason.

Why do you think Tintin had that effect on you?

I’m surprised no one talks about the paranoia in Tintin. Death and danger lurk around every corner. Take Tintin in America, for example—he can’t even get into a car without a mobster trying to kill him. If someone is kind to him, it almost always turns out they're secretly a gangster. Many Tintin stories work that way.

A not-so-bold psychoanalytic interpretation would be that your school experiences shaped this reaction. It’s hardly surprising that someone who spent their school years constantly on edge, always aware that an attack could come at any moment, wouldn’t find much enjoyment in a story where the hero is perpetually facing death.

Maybe. Yeah, you’re probably right. Actually, yes—you’re right.

Founding Cornélius

In 1991, you created Cornélius. Where did the name come from?

Nowhere—straight from my subconscious. I was searching for a name, so I visited bookstores for inspiration, looking at the names of other publishing houses. I noticed they mostly fell into two categories: either they carried the founder’s last name—always a man, never a woman—or they had a symbolic, poetic name that hinted at their identity. I found the idea of using my own name ridiculous, so I went with the second option. For days, I made lists of potential names—expressions, symbols—all of them terrible. The whole exercise felt absurd, but I was barely in my twenties, so I’ll blame it on that.

At one point, I thought I’d struck gold with Éditions de Minuit, only to realize, to my horror, that it already existed—and was one of France’s most important literary publishers. I felt completely ridiculous. That’s when I decided to take another approach: what if I just invented a name for a fictional publisher? I made a new list, and the first name I wrote down was Cornélius. It sounded good, so I ran with it. Then I had a beer [laughs]. Later, I realized the name wasn’t entirely random. There’s a fairly well-known French pulp fiction writer, Gustave Le Rouge, who wrote The Mysterious Doctor Cornélius, which I read as a kid. Cornélius was also the name of Roddy McDowall’s character in my favorite film, Planet of the Apes, and, of course, the grandfather in Babar is called Cornélius too. So, in the end, I guess it wasn’t just pulled out of thin air.

And you also created the fictional character Sagamore Cornélius—the invented father of the company—who frequently signs editorials and other texts published by Cornélius. Not to mention his many fictional children, who write about their father in company publications. Social media posts are often signed by Gilbert, who…

…is our pig! Since the family was so poor, he has been killed and eaten many times.

Ah yes, the Sæhrímnir of alternative comics—like the mythical Norse pig that is eaten every night and reborn the next day.

I actually came up with the first name Sagamore later. Initially, he was just “Cornélius.” I was really pleased with the idea—and believe me, I’m not often pleased with my own ideas—so I ran with it. Sagamore is a man with a ridiculous number of children from different women. In the end, they all became so poor that he had to put them together in one house, and that house became a publishing company. That’s the story, that’s the legend.

I even designed the characters, and for every annual catalog we published, I asked a different Cornélius artist to contribute their vision of them. Plus, all our book collections—Paul, Kim, Solange, etc.—are named after Sagamore’s children.

Okay. But I’m still not sure I get the point of this elaborate backstory. Why go through all the trouble of creating a family tree?

I thought it was funny. So why not?

First steps in the world of publishing

The first project released under the Cornélius name was a set of puppets based on Robert Crumb’s characters.

Anouk Ricard’s interpretation of Sagamore Cornélius on the cover of a Cornélius book catalogue.

Anouk Ricard’s interpretation of Sagamore Cornélius on the cover of a Cornélius book catalogue.At the start of Cornélius, I worked with silkscreen printing, and the puppets were produced using that technique. At the same time, I was also creating silkscreen posters in collaboration with Jean-Christophe Menu, Yves Got, and Killoffer. I had a wishlist of artists I hoped to work with, including both Crumb and Willem. Publishing Crumb felt impossible at the time—he was a huge star, and I was just a small-time publisher starting out. The puppets were a relatively minor project, but they still required some effort to make them work. I reached out to his agent, Lora—who was Gilbert Shelton’s wife—and she was initially skeptical about granting me permission, as I was an unknown. However, since it was such a small project, she eventually agreed. When I met Robert Crumb at the Angoulême festival the following year, he told me he was pleased with the results. That was my first contact with him. Since he liked my work, I suggested publishing a small silkscreen-printed book of his drawings. He was open to the idea.

I decided to print a selection of drawings from a sketchbook he had created for Harvey Kurtzman’s magazine Help!. These included sketches from Harlem as well as from a vacation in Bulgaria with his wife. However, I only had my own copies of Help! to work with and the printing in those were of a very poor quality. I also had the Complete Crumb books from Fantagraphics, but they used the same low-quality source material. I went ahead with the book but had to spend an inordinate amount of time trying to clean up the messy lines and enhance the images. Despite my efforts, it was impossible to get the quality I wanted. I was deeply dissatisfied with the final result and couldn’t stand by it. In the end, I pulled all the books from the bookstores and destroyed them. It was my first failure.

Sounds like an expensive failure. How many copies did you destroy?

In 2007, Cornélius published a book about its early years, with a cover illustrated by Robert Crumb, who reimagined Sagamore Cornélius—the company’s fictional patriarch.

In 2007, Cornélius published a book about its early years, with a cover illustrated by Robert Crumb, who reimagined Sagamore Cornélius—the company’s fictional patriarch.All 500 copies I had printed. It was indeed costly. I lost all my savings because of it and had to return to working as a silkscreener to keep Cornélius afloat. However, I promised Robert that I would try to track down the original drawings and, if I found them, I would make the book the way I had originally intended. He suggested that Kurtzman might still have them. I called Kurtzman, and when he picked up, he told me, ”Okay, let me check.” He left me on hold for about fifteen minutes, during which all I could think about was how much this long-distance call was going to cost me. Eventually, he returned and said, ”Sorry, I can’t find them, but I’ll keep looking. Call me back in three weeks.” Three weeks later, he was dead.

Seven years later, Robert called me to say that he had gained access to Harvey’s archives. He hadn't found the originals but had come across a set of Xerox copies that were far better than the ones I had previously used. He sent them to me, and I was able to create a new version of the book. The clarity was so much better that it finally turned out as I had envisioned. That was a small personal victory, but the first fifteen years of Cornélius were marked by a long string of failures and a constant lack of money.

In the book Cornélius ou l'art de la mouscaille et du pinaillage, you describe some of these struggles. One of them involved the second book you published, Willem’s Alphabet Capone in 1993.

The book itself was well done, and Willem was very happy with it, but I couldn’t get the binding to work properly. I was doing it manually, and I just couldn’t get it right. I printed 500 copies, but in the end, I only managed to complete 350. The remaining pages are still sitting in boxes in my storage. It’s far too late to finish them now.

Were you a big fan of Crumb and Willem growing up? They both emerged in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, which makes them an unconventional choice for a new publisher. It would have been more typical to launch the careers of artists from your own generation.

I was more curious than a die-hard fan of underground comics. My feelings were mixed. When I first read Crumb, I was both attracted and repulsed. The French translations were often poor, making some of the stories difficult to fully grasp. But even beyond that, there was an aggressiveness in his work that unsettled me as a teenager. Over time, though, his work grew on me, and he became one of my favorite artists.

Fair enough. My question was probably poorly formulated. What I was getting at is the fact that you initially published well-known cartoonists and only later started publishing work featuring France’s up-and-coming artists. You’ve already mentioned Jean-Christophe Menu, whose Mune Comix you published, along with Lewis Trondheim’s Approximate Continuum Comics and David B’s Le Nain Jaune. Walk me through that.

Jean-Christophe Menu’s Mune Comix, featuring a screen-printed cover.

Jean-Christophe Menu’s Mune Comix, featuring a screen-printed cover.When I worked as a clerk at a bookstore in Pigalle, I met Jean-Christophe Menu because he lived in the neighborhood. We weren’t close friends yet, but we knew each other and kept in touch. Our friendship developed after we collaborated on the silkscreen poster I mentioned earlier. After that, I encouraged him to make comics. His challenge was that soon after launching L’Association, he became too busy with publishing. But I kept pushing him, and one day he suggested that perhaps I could publish his work instead. Of course, I agreed. In 1993, we released the first issue of Mune Comix.

Soon after, Trondheim and David B approached me, saying that L’Association couldn’t publish all the books they wanted to release. They asked if I could publish some of their works instead. Again, I said yes. It was a fantastic opportunity, but it also created a problem: for a long time, Cornélius was perceived as a satellite of L’Association. People assumed we were an extension of them rather than an independent publisher. It took years to shake off that misconception.

Jean-Christophe Menu’s Mune Comix, featuring xeroxed interiors.

Jean-Christophe Menu’s Mune Comix, featuring xeroxed interiors.One distinguishing feature of Mune Comix, Approximate Continuum Comics, and the other comics you published was that the covers were high-quality silkscreen prints, while the interiors were just simple Xerox copies.

I was poor, so I worked with what I had. Since I was still employed at a silkscreen printing house, making covers that way was easy. The interiors were Xeroxed because it was the cheapest option. I had a friend who worked with photocopiers and would call me whenever he got a new machine. The one I used for these comics was excellent—it made the black lines really pop. The Xerox machines from the ’90s were great.

How did they sell?

Not bad at all. It wasn’t a massive success, but each issue sold better than the last. The real problem was me—I was too slow at reprinting issues when they sold out. Eventually, another issue arose: Menu and I had a falling out when he decided to compile pages from Mune Comix into a book, which he published with L’Association.

You mean Livret de phamille (1995)?

Yes. I felt betrayed, and we had a heated argument. Around the same time, Trondheim had just finished his Approximate Continuum Comics story, and David B was growing tired of Le Nain Jaune, so I decided to stop producing those fanzines. Trondheim later pitched me another project, but it leaned too heavily into heroic fantasy, which wasn’t my taste. That project eventually became Donjon [big and long running series published with Delcourt]. Instead of focusing on comic book-style publications, I shifted to publishing works in a more traditional book format, leading to Blutch’s Mitchum and David B’s Les 4 Savantes [both in 1996]. At this point, I also abandoned silkscreen printing for covers—it was too labor-intensive for print runs of 1,500 copies. Instead, the entire book was produced in offset printing.

You didn’t get to publish Livret de phamille, but you did publish the collected Approximate Continuum Comics [published in English by Fantagraphics in 2011]. Was that your first commercial success?

Oh yes. For a long time—probably around 15 years—Approximate Continuum Comics was Cornélius’ bestseller. Then we acquired Crumb’s Mister Nostalgia and a few other titles that performed very well.

L’Association was vocal about pushing the boundaries of the medium by publishing works that defied the conventions of major publishers. Were you guided by a similar credo?

Not at all. Firstly, I was more uncertain about what I wanted to do and why I was doing it than the guys at L’Association. I was guided more by instinct than by theory or ideology. I’ve always been suspicious of my own taste. It probably took me 10-15 years to develop a strong sense of what I was looking for.

Secondly, L’Association benefited from significant media attention, while Cornélius largely went unnoticed. I rarely had opportunities to discuss the books I published or share my opinions on the state of comics.

Thirdly, I had a big problem with capitalism, selling books, and making money. I had a romantic notion of publishing, which, in hindsight, was naive—after all, when you’re a publisher, you’re also a seller. It’s all commerce. At the end of the day, publishing is more business than art. To sum up, my approach was simply to create beautiful books that made the artists I collaborated with happy.

With your focus on design and the book as an artistic object, there seems to be a kinship between you and Étienne Robial at Futuropolis.

I don’t know. I think I was more interested in comics than Robial. He was more into design than I was. We have very different personalities. I don’t feel much connection to him.

I own a lot of Futuropolis books that I bought at a sale, but I’m not like Jean-Christophe Menu, who is very nostalgic about Futuropolis. It was never my favorite publishing house. I preferred a small company called Artefact, which published Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, and Italian and Spanish artists from the 1970s. That was much more my taste. It was also through Artefact that I first discovered the works of Yoshihiro Tatsumi.

Before we get to Tatsumi, I’d like to discuss the French artists you started publishing and promoting in the ‘90s. You’ve already mentioned Blutch, but there’s also Pierre La Police, Dupuy & Berberian, and others.

I was very lucky to come across these artists. The comics scene in Paris wasn’t that large, so you would run into people making comics or get recommendations like, “You have to check out this comic by Pierre La Police.”

At the same time, as I said earlier, I didn’t trust my own taste. I knew that I didn’t know enough. So I had to teach myself. It was a constant internal struggle between my curiosity and my lack of confidence.

Did you seek advice from others when deciding what to publish?

No, never. I preferred making mistakes on my own rather than relying on others.

That sounds rather proud of you.

Thankfully, I’ve changed since then. But that’s not to say I was uninformed or uncultivated—I read extensively and felt more knowledgeable than many others in the French comics scene at the time.

Were you self-taught?

Yes. David B was a great person to talk literature with—he’s incredibly knowledgeable.

Early Cornélius publications by David B. and Blutch.

Early Cornélius publications by David B. and Blutch.Since you published several co-founders of L’Association and even some of the same artists – for instance, Joann Sfar, Dupuy & Berberian, Blutch, and others – I find it understandable that many people may not have seen a clear distinction between Cornélius and L’Association.

It was a special relationship because the guys at L’Association could be intimidating—they were warriors. But individually, they were very different. I had friendly relationships with Menu, David B, and Killoffer. I also got along with Lewis Trondheim, though maybe not as closely. Same with Mattt Konture. They helped me several times because they wanted Cornélius to survive. So, it’s complex.

A page from Jean-Louis Gauthey’s comic reflecting on his interactions with L’Association over the years, published in Quoi! (L’Association, 2011).

A page from Jean-Louis Gauthey’s comic reflecting on his interactions with L’Association over the years, published in Quoi! (L’Association, 2011).When was the first time you could live off Cornélius?

In 1998, I concluded that I would never be able to live off Cornélius—it was impossible.

Was Cornélius still a one-man show at that time, or did you have employees?

I hired my first employee in 1998. Although I had stopped making silkscreen covers for my own books, I still worked as a silkscreener for other publishers. Most of the money needed to publish our books came from that job.

I knew that working with Cornélius meant I would stay poor my whole life. By 1998, I was debating whether to shut it down or find additional work. A friend suggested I try writing for television. He said, “You have a great imagination; you can make easy money this way.” I asked what I needed to do. He gave me a contact, I made the call, took a writing test, and was hired.

Inside Cornélius office.

Inside Cornélius office.This was during the early days of France’s animation boom, with Gaumont and Pathé launching their own studios. I arrived at the right time because studios were desperate for writers. But working in animation scared me. The pay was so good that I couldn’t understand why it was so easy to make money in animation but impossible with Cornélius. One day, I challenged myself to spend my entire advance in a single day. I took taxis around Paris, bought books and clothes, and ate in fancy restaurants. By the evening, I was exhausted, but content because I had not even managed to spend half of the money—it reassured me that I was still a simple guy at heart.

I used part of my animation earnings to keep Cornélius afloat. Then, in 2000, my father passed away, and I inherited a decent sum, which also helped. I even had a meeting with Delcourt when they expressed interest in buying Cornélius. In the end, they declined, saying we were too small. But talking to Guy Delcourt taught me a lot about running a business. He asked for financial documents that I couldn’t provide because we didn’t even have an accountant. That experience pushed me to professionalize Cornélius. From that point on, I decided to publish only what I truly loved.

Bringing Clowes and Burns to France

In the late ‘90s and early 2000s, Cornélius introduced some of the most prominent American alternative cartoonists, like Daniel Clowes and Charles Burns. Were you a loyal reader of Eightball?

I loved American comics in the ‘90s. I wasn’t a fan of Lloyd Llewellyn—it felt too influenced by the French scene of the ‘80s. But when I picked up the first issue of Eightball, I knew Clowes was special. I asked for the rights early on but didn’t want to publish his work in a comic book format, I wanted to wait for a book. The first book we published was Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron.

Did it sell well in France?

Not so good. David Boring did slightly better, but it took time. Even today, Clowes isn’t a big seller in France and that’s a shame—Burns, however, is. It’s the opposite of the U.S., where Clowes is the bigger name.

Dan and I had a good relationship, and he’s a big admirer of the Cornélius catalog. I think he was a bit skeptical at first, though, since the cover I designed for Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron wasn’t my best work. That wasn’t entirely my fault—I had very little material to work with, and Dan didn’t want to draw a new cover for the French edition. But after that, he gave me free rein over the design. At the time, imported comics were widely available in French bookshops, so it was important for us to create a distinct visual identity for the French editions.

And shortly after, you added Burns, Chester Brown, and others to your roster?

I never had to work very hard to bring artists to Cornélius. When you publish great books by great artists, other great artists naturally want to join you. If you’re already publishing Crumb and Clowes, it becomes easier to attract Burns—it’s all connected.

In Burns’ case, he was already aware of Cornélius. He had visited France several times and frequented Un Regard Moderne, an excellent bookshop in Paris where he had seen our books. So when I reached out to propose new editions of Big Baby and El Borbah, he was immediately on board.

Parts of Gauthey’s bookshelf at the Cornélius office.

Parts of Gauthey’s bookshelf at the Cornélius office.Now you publish Burns’ books in French before they appear in English.

Yes. We have a very strong relationship. I like to think I have closer ties with my artists than most publishers do. Although I complain a lot about my life and the state of Cornélius, getting to work with someone like Burns just proves how incredibly lucky I really am.

Another thing we need to discuss is that you recently lost the rights to Clowes’ work after Fantagraphics increased the fees, and you were outbid by Delcourt.

I found the situation a bit ironic, considering Delcourt has tried to buy Cornélius four or five times. Guy Delcourt must have realized he made a mistake by not acquiring us back in the late ’90s. We’ve never been a huge success, but the company has steadily grown over time. Every time he approached me about buying Cornélius, I said, “Thanks, but no thanks. And it’s thanks to you that I learned how to run a company properly.”

We’ve had our share of disputes over the years, and I believe Delcourt is someone who neither gives up nor forgives. I think he saw an opportunity to retaliate, to punish Cornélius—and me personally. In Les éditeurs de bande dessinée (2005), a book about publishers in the ’90s, Delcourt even states that his dream is to publish Daniel Clowes.

In the end, we lost the rights to four of Clowes’ books, which Delcourt took from us, as well as two more they acquired from Rakham, in addition to Monica, Clowes’ latest masterpiece. What’s interesting financially is that Delcourt isn’t selling more of Clowes’ books than we did, despite being a much larger company with a major distribution network. Of course, Monica has sold well, especially after winning the Fauve d’Or at Angoulême in 2024. But it’s still far from what they expected, for what I know.

In my opinion, Clowes is among the top three greatest cartoonists in the world, but there’s something inherently American about his work that doesn’t necessarily resonate with French readers the same way other artists do. He has a following here, of course, but it’s nowhere near as large as in the U.S. The best-selling Clowes book we ever published sold somewhere between 15,000 and 20,000 copies. Except Ghost World, of course, which was a big hit.

You didn’t stay quiet after losing the rights to Clowes’ work. You continued selling his books at a discount, got sued by Delcourt for it, and launched a crowdfunding to cover your legal fees.

I have a strong moral and political stance when it comes to the book business in France. While I don’t see myself as an activist in the same way, it’s not so different from what Menu did at L’Association. As the publisher of an independent press that’s been around for quite a while, I’ve gained some insight into the industry. One thing I know for certain is that in France, we destroy more books than we sell. And I have a serious problem with that—ecologically, economically, and morally.

And that’s why you sold your backstock of Clowes’ books for 15 euros apiece, despite no longer holding the rights?

Exactly. We launched the campaign for two reasons. First, at Cornélius, we don’t destroy books. I’d rather give them away for free than have them pulped. Second, I see it as my moral obligation as a publisher to produce the best books possible and ensure they reach as many readers as possible.

Without getting into too much detail, Fantagraphics didn’t give us all the necessary information when we lost the rights. They never sent an official letter stating that our contract had been terminated, and they continued accepting the royalties we sent them. From our perspective, the agreement had never been formally dissolved. Under both French and American law, we had every legal right to do what we did.

Of course, I knew Delcourt wouldn’t be pleased that we were selling our remaining stock of Clowes’ books, and I fully expected them to sue us. But that didn’t scare me—in fact, I looked forward to the opportunity to present my side of the story in court. It was also a chance for Clowes to reach a new audience. I’ve personally discovered plenty of great artists in discount bins. But naturally, Delcourt saw things very differently. To be honest, I doubt Delcourt even likes comics—he’s a businessman. He operates with a checklist, and signing Clowes was on it. Punishing Cornélius might have been on it, too.

In any case, I think we managed to introduce Clowes to a few new readers by selling his books at an affordable price. And while we ultimately lost the lawsuit, it was a small victory for Delcourt. He sued us for around 80,000 euros, but in the end, we only had to pay 3,000—a symbolic sum, based on the revenue we made from selling Clowes’ books at a discount.

And then you launched the crowdfunding campaign to cover the legal fees.

When Delcourt sued us, I made it clear to both him and his lawyer that I refused to stay silent about the situation. I told them I would share every detail at every opportunity so people could get the full picture. So, I made a public post explaining everything—how we lost the rights to Dan’s work, the lawsuit, and the whole sequence of events.

We actually received a lot of support, both in terms of encouragement and financial contributions. The campaign was quite successful, so in a way, the trial wasn’t so bad after all as it offered a good opportunity to explain how the market push to destroy books without any moral consideration.

Has Daniel Clowes said anything about the whole thing?

Yes, he has. But I can’t repeat what he said—it will stay between us.

Discovering Japanese Artists

You mentioned Yoshihiro Tatsumi earlier. In the early 2000s, Cornélius started publishing various gekiga artists, including Tatsumi, Shigeru Mizuki, and Yoshiharu Tsuge. Walk me through what led you to start publishing Japanese artists.

I first became aware of Japanese comics as a teenager in the 1980s when I found a book by Tatsumi in a secondhand bookstore. The book in question was Hiroshima, published by Artefact.

Was Artefact the only publisher releasing Japanese comics aimed at an adult audience in the 1980s?

Not entirely. Les Humanoïdes Associés made an attempt with Barefoot Gen [by Keiji Nakazawa, translated into French in 1983], but it was a commercial failure. Then Artefact published a book by Tatsumi, and it was an even bigger failure. There was also a Swiss magazine called Le Cri qui tue [published between 1978 and 1981], which tried to introduce French readers to the idea that manga could be just as sophisticated and compelling as American or European comics. But they were ahead of their time, and they failed as well.

So what made you decide to start publishing manga after all?

Parts of Gauthey’s bookshelf at the Cornélius office.

Parts of Gauthey’s bookshelf at the Cornélius office.Initially, I had no interest in publishing manga because I didn’t know enough about it. And in the ’90s and early 2000s, several French publishers were already translating manga, so I assumed they knew what they were doing and that the best books were already being published. And frankly, they weren’t very good or interesting. But at one point, I met a Japanese independent publisher, Mitsuhiro Asakawa, who had come to France to sell works by underground Japanese artists. I remember reacting with surprise, saying something like, “Oh, so there’s an underground scene in Japan too?” And the moment I said it, I realized how stupid I sounded. Of course, there had to be an underground scene—every industry has one. It was obvious.

I told him, “Maybe I should visit Japan and learn more.” He responded, “Yes, come. I will teach you about the history of manga.” So, in 2002, I took my first trip to Japan, and I was completely overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of books I found there. The diversity and complexity of Japanese comics were far beyond anything I had imagined. I was astonished. I found so many incredible books that I started filling boxes—one after the other. By the end of that trip, I had shipped ten large boxes of comics back to France.

Over the following years, I traveled to Japan four times a year, trying to better understand the scene and what was being published.

I can tell by your fantastic collection of Japanese toys and books in your office.

Well, this is only a part of my collection. Anyway, the more I learned, the more I realized that I could contribute something new to the manga scene in France. At the time, the market was focused on a very specific kind of manga, while an entire side of Japanese comics remained invisible to French readers. I wanted to show that the scene was far more complex and diverse than people assumed.

Mizuki was a great starting point for introducing French readers to another side of Japanese comics because his work is quite accessible. Some aspects of his art style might have been a little strange for a French audience, but I was confident that his books would find a readership. It took a few years, but we succeeded.

I don’t think we changed the manga market in France—the market evolves on its own. But I do think we helped, even if just a little. Not least by the way we approached book design. Our editions were larger, better printed, and higher quality than most manga releases at the time. True, our books were more expensive, but they offered readers a completely different experience.

Through this, we introduced manga to new audiences—not necessarily teenagers, but older readers, intellectuals, and women. A much more diverse group. Mizuki has sold well, and Tatsumi has done decently. The other artists, unfortunately, haven’t sold as well. But even if someone like Katsumata didn’t sell much, I’m still incredibly proud to have published his work.

Given the popularity of Japanese comics in France—evident in the growing number of stores dedicated exclusively to manga and the expansive tent devoted to Japanese comics at Angoulême—one might assume that this segment represents a significant portion of Cornélius’ revenue.

Indeed, Mizuki, for example, sells very well. However, there is no direct connection between the broader manga market in France and what Cornélius publishes. We never label our books as “manga,” nor do we make any distinctions between different types of comics—everything we publish is manga, comics, or bande dessinée. I see no value in categorizing works based on geographical origin. For instance, the Japanese artists we publish may not necessarily have anything in common aesthetically simply because they come from the same country. In the case of Mizuki—or even more obviously with [Toshio] Saeki—I see a clear artistic connection with American creators like Charles Burns. But there is no such connection between Saeki and [Osamu] Tezuka. For me, territorial distinctions are irrelevant.

Recent publications from the “Kim” collection, including works by Charles Burns, Antoine Cossé, and Louis Chalumeau.

Recent publications from the “Kim” collection, including works by Charles Burns, Antoine Cossé, and Louis Chalumeau.You also mentioned Tsuge earlier. It took me ten years to introduce his work to a French audience. While sales are modest, they are steady. However, I think Tsuge is a challenging read for many French readers. The world is constantly evolving, and his stories, written in the 1960s, were provocative even at the time. For today’s readers, they may seem particularly aggressive, insensitive to contemporary gender norms, or even offensive. I fully understand why some might feel shocked or insulted by his work. But that is part of the history of the medium. The same can be said for Crumb and many other great artists—their stories were created within a specific historical and cultural context, and we now read them through an entirely different lens.

Publishing Identity

In addition to publishing Japanese and American artists, as we’ve already discussed—along with classic French cartoonists like Nicole Claveloux—the fourth pillar of your publishing strategy seems to be contemporary French artists such as Antoine Cossé, Louis Chalumeau, and, not least, Jérôme Dubois, whose Immatériel was one of the best books published in 2024.

Parts of Gauthey’s bookshelf at the Cornélius office.

Parts of Gauthey’s bookshelf at the Cornélius office.Oh, cool! I’m glad to hear you enjoyed Jérôme’s book.

However, this is a big and difficult question. In the beginning, when Cornélius first started, I couldn’t even define its identity myself—what kind of books we were meant to publish felt too abstract and unclear. Over the years, I’ve met plenty of people who’ve told me what they think Cornélius is, and what we should or shouldn’t publish. You can listen to them, but you don’t have to believe them.

For example, in Cornélius’ early years, people used to say I was a publisher-printer, that Cornélius was synonymous with silkscreen covers—and that was it. Sure, that was part of what we did, but it wasn’t the whole picture, and we were already evolving in another direction. When I published Necron by Magnus, some people reacted by saying, “That’s not Cornélius. You’re a classy, highbrow publisher—you can’t sully your hands with this kind of grotesque pulp and pornography.” To them, I simply say: “Yes, I can publish it.” Because I find it interesting. And, in fact, I find it particularly interesting to place a book by Magnus next to one by Charles Burns—because there are connections between the two, even if people refuse to see them.

Then, when I started publishing manga, some people had an outright meltdown, claiming, “Cornélius isn’t Cornélius anymore!” You wouldn’t believe how many times I’ve heard that reaction. But after I actually get them to read the books, they always come back saying, “Oh, I was wrong. Manga is great.”

What would you say is the essence of Cornélius? And do you follow a specific publishing strategy or direction?

I would say Cornélius is built on three key pillars: the first one is creation. I’m interested in what’s being published today by new artists—discovering voices that push the aesthetics of what we already do. The second is heritage. We don’t come from nowhere. We’re part of a lineage. I was influenced by artists from the 1970s, who in turn were shaped by artists from the 1950s, and so on. I find it fascinating to publish works from different eras, placing them side by side to reveal their shared connections. The third is translation. We want to showcase the diversity of comics from around the world. I hope Cornélius can present a spectrum of tastes and aesthetics—across different countries, time periods, and artistic sensibilities. Whether it’s Crumb, Mizuki, or Jérôme Dubois, each of them speaks to me in different ways.

As a publisher, what do you look for when reviewing a submission? Or, to put it another way, what should a cartoonist do to catch your attention?

Just send me a PDF of what you’re working on. That’s it.

That said, we receive a lot of submissions—it takes me an entire day every month just to reply to them all. I actually have 25 pre-written drafts that I use for responses, but sometimes, I need to reply personally. The truth is, 90% of the submissions we receive aren’t right for Cornélius. They don’t match our editorial vision or our standards of quality, and it’s clear that many of the artists don’t even know what kind of books we publish. But when I do receive a solid submission that doesn’t quite fit our catalog, I try to recommend other, more suitable publishers.

And if a submission is really awful, you tell them to try Delcourt.

Gauthey next to a statue of Kitaro.

Gauthey next to a statue of Kitaro.[Laughter] No, I wouldn’t do that.

But sometimes, I do receive a submission that makes me hesitate. It may not feel exactly like a Cornélius book, but I’ll have this internal debate—maybe it’s not too far off, maybe it could enrich our catalog. Another challenge is that I’ve decided we can’t publish more than 15 books a year. Publishing a book isn’t just about producing it—it also takes time to promote and sell it properly. Since there are only 12 months in a year, that means some months we release two books, and I don’t want to put our artists in competition with each other. We need to be able to fully support every book we publish. Fifteen is the number that makes sense for us—it’s what we can handle.

What did Dubois do to catch your attention?

Actually, both he and Ludovic Lalliat sent their first manuscripts by mail. But I can’t explain exactly what I’m looking for—there’s no formula, nothing rationalized. It’s pure instinct.

So, basically, you just know it when you see it?

Yes. In that sense, I’m still the same as I was 30 years ago.

The transcript has been edited for clarity by both Aman and Gauthey.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·