Nicholas Burman | November 26, 2024

Dave Cooper has made a career out of creating work that makes you look twice. At first glance his comics could be mistaken for a still from a Fleischer Studios cartoon, one where the artist has been given a little more free reign than usual, perhaps. Then you check again, and start to see the weirdness of it all – the unusual bulging bodies, characters who seem elated, but are actually deeply disturbed. You spot that Cooper's worlds aren’t solely composed of concrete and steel, but, in – a manner reminiscent of Jim Woodring – of organic matter, bubbling up. Cooper's latest book, Dog Head, teeters atop ramshackle foundations: in one story, the aesthetic style actually becomes a plot point, as an architect hopes to build something that metabolises and is “able to grow."

Dog Head #1 is the first in a new six-part series by the Ottawa-based artist. Cooper is an autodidact, high school dropout inspired by Jodorowsky, and has won praise from Guillermo del Toro and David Cronenberg. This series is composed of two distinct stories and is, like 2018’s Mudbite, bound tête-bêche, meaning that the two stories start on the opposite ends and flipped sides. Another similarity to Mudbite is that Eddy Table, a recurring character in the Cooper universe, makes a return.

Eddy appears in ‘The Great Hierarchy," wherein he is living in an apartment in the reto-futurist Atro City (one can spot here signs of Cooper’s involvement in Matt Groening’s Futurama). There is also a very different level of this reality where pagan gods bring people to life, mostly by harvesting them from the ground and then BBQ-ing them into consciousness. The tagline to this story is "a love letter/goodbye note to creativity" and Cooper is arguably developing an allegory about the creative process. It’s not so much a daydream from whence gentle ideas come, but a painful and often disappointing process beset by little devils waiting to spoil the party.

It won’t surprise Cooper's long-term that the creative process also involves quite a bit of surrealistic investigation into the subconscious. Throughout Dog Head, there’s enough primal eroticism, pestilence and flesh to make Robert Crumb proud (though Crumb allegedly found Cooper’s 1990s Puke and Explode a bit much). In the case of the "The Great Hierarchy," its gods are bulbous sacks. The feminine ones have their hair, eyes and breasts accentuated (one with large eyes where her nipples should be), while the masculine one has a head resembling a phallus with a massive eyeball on the end, and boasts a prominent phallus that is identical in structure to his head.

It won’t surprise Cooper's long-term that the creative process also involves quite a bit of surrealistic investigation into the subconscious. Throughout Dog Head, there’s enough primal eroticism, pestilence and flesh to make Robert Crumb proud (though Crumb allegedly found Cooper’s 1990s Puke and Explode a bit much). In the case of the "The Great Hierarchy," its gods are bulbous sacks. The feminine ones have their hair, eyes and breasts accentuated (one with large eyes where her nipples should be), while the masculine one has a head resembling a phallus with a massive eyeball on the end, and boasts a prominent phallus that is identical in structure to his head.

Drawing on his passion for music, Cooper originally planned to make this story an opera. The characters themselves were first devised for a reimagining of Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, which makes this the second time this year I’m discussing a comic that has been explicitly inspired by Bosch and that work specifically. But Cooper isn’t elaborating on art history here, instead he takes the characters in the Garden literally, asking what their world would be like, and recognizing an approximation between creationist myths and the act of human creation.

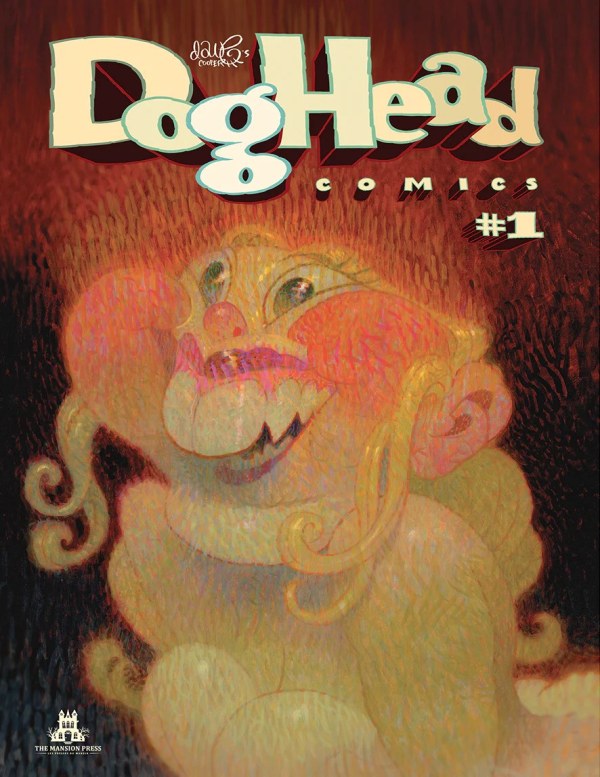

Cooper has made a name for himself as a fine artist, and one of Dog Head #1’s covers, portraying a buxom and buck-toothed woman, is an oil painting done in his typical, dreamlike (or nightmarish, depending on your POV) style. Other critics have referenced Otto Dix in relation to Cooper’s work and, like the New Objectivity movement (and a tendency for male alt-cartoonists since the days of Zap), Cooper is interested in accentuating the fleshy, erotic elements of the female body, depicting his subjects at their most sexual, while also having a somewhat critical filter over proceedings. It’s a paradoxical interest into the outré in which the narrative eye can’t help but look, but also can’t help but feel bad about looking, placing a degree of moral concern on its subjects. This is decidedly the case in "L’architecte," in which an architect visits a visionary peer. The story is full of references, explicit and otherwise, to sex the people at this secluded residence are having, with our architect protagonist both shocked and clearly keen to stick around and see more.

Despite Cooper's time spent in the fine art world, Dog Head is certainly not weighed down with pretension. The art is hyper cartoonish. The main flourish Cooper has allowed himself is the offbeat color palette. A burgundy red is used for characters and the foreground, while a chalk black is used for the background and buildings. In an interview with Cartoonist Kayfabe, Cooper describes oil paint as “lurid and sensual”. That might speak more to his application of his tools, as that phrase could certainly also be attributed to Dog Head’s kinetic visual style.

Being the first in a series, there’s a limit to what can be said about the story overall at this point. What I can say is that Dog Head is a strange, engrossing read from a master cartoonist. Completists will also appreciate that the limited edition hardback version of #1 comes with additional pages of doodles from Cooper’s sketchbook. Not everything on show here is necessarily pretty, but like one of Cooper’s protagonists, I can’t seem to look away.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·