The Editors | January 16, 2025

Courtesy of Fantagraphics, today we are pleased to share an excerpt from Tell Me A Story Where The Bad Girl Wins: The Life and Art of Barbara Shermund by Caitlin McGurk. Below is McGurk's selection from chapter 2, but first, a few words from Emily Flake's foreword:

Is that Shermund’s story—one where the bad little girl wins out? Not exactly. Shifting societal preferences—which no longer found her provocations amusing—hobbled her postwar work. The freedom afforded women in the flapper era, the Depression, and in their wartime employment in traditionally male roles contracted as the men came home, weary and desperate for a conflict-free version of normalcy. Society didn’t want to see women in bars, it wanted to see them in kitchens. And so Shermund’s work was tamed. Keeping a roof over her head required defanging her wit. But the trail she blazed never grew over entirely, and her work—brash, sexy, and, above all, funny, remains an inspiration even today. Barbara Shermund, in her diabolically dainty little heels, danced so that we could run.

-Emily Flake

The first issue of The New Yorker debuted on February 21, 1925, with Irvin’s Eustace Tilley creation adorning the cover, gazing, unimpressed, at a butterfly through his monocle. Thirty thousand copies were printed, 18,000 of which hit newsstands across New York City and sold out within forty-eight hours. The remaining 12,000 were distributed across the country. Subscriptions could be ordered at the rates of 26 issues for $2.50, and 52 issues for $5.00. Surprised and encouraged by the success of the first issue, they set forth printing 40,000 copies of the second issue. Filling those first dozen or so issues proved to be a challenge. Unable to pay much beyond stock— he relied largely on friends who were established writers and artists with loyal affiliations and steady paychecks from elsewhere (often contributing to The New Yorker under pen names)—Ross needed new blood. In Dale Kramer’s definitive book, Ross and The New Yorker, he describes some of the artistic failings of those early issues: “To the aesthetic eye, the magazine’s typography was, however, unappealing. Department heads were cluttered with gingerbread. Vowels about one sixth of the size of the consonants made the heading type outlandish.”

The cartoons included were also not quite hitting the mark. Leaning too hard on the style of the old humor weeklies—despite Ross’s best intentions—the almost indefinable recipe of what “a New Yorker cartoon” would come to mean had still not found its form. The old style of captioned cartoons generally relied on a two-line format—the set up and the punch line—often a conversation between two characters. One early piece of feed- back Ross received that didn’t sit right with him was the interpretation of The New Yorker as a humor magazine. He wanted it to be witty and biting; of equal importance, it need- ed to be topical and smart. Ross also had a distinct recipe in mind for the sort of cartoons The New Yorker could run. He wanted the artwork—be it the section mastheads, the illustrations and covers, and especially the cartoons—to be illustrative of ideas, rather than decorative. In a letter to the art contributors in early 1925, Ross outlines his vision for the magazine’s art: “We want drawings which portray or satirize a situation, drawings which tell a story. We want to record what is going on, to put down metropolitan life and we want this record to be based on fact—plausible situations with authentic back- grounds. A test for these is, ‘could this have happened.’”

LEFT: Barbara Shermund’s first cover for The New Yorker, June 13 1925. RIGHT: Barbara Shermund’s second cover for The New Yorker, October 3, 1925.

LEFT: Barbara Shermund’s first cover for The New Yorker, June 13 1925. RIGHT: Barbara Shermund’s second cover for The New Yorker, October 3, 1925.This last line became the mantra of the art meetings held each Tuesday. This was the one day per week that Rea Irvin came into the office. Together, with Ross and a rotating cast of editors and staff (in the early days of the magazine, editors and contributors were often interchangeable, and everyone played different parts) reviewed submissions. Ross was particularly wary of what he frequently described as “custard pie” humor and situations—slapstick was the standard fare for most magazine and newspaper cartoons of the era. He wanted sophisticated humor, but not alienating—ironic, in retrospect, considering the reputation that The New Yorker cartoons would eventually hold.16 Further, while having a sophisticated sensibility, the cartoons could and should poke fun at the very urbanites it depicted and was read by. Situations with smart settings were encouraged, such as scenes on Fifth Avenue or in the theater, drawing room, garden, or gallery. He wanted the rest of the world to see New York life through the lens of the magazine’s art, and he encouraged the contributors to go out and sketch what they saw and experienced to capture situations around the city that felt particular to New York. The cartoons were to be as much about the vogue of the time as they were about mood and manner. It was essential that the artists keep up with current events and trends: think ahead to the coming seasons and what activities they would yield. While the focus was on metropolitan types, the settings should match anywhere these types might go throughout the year. Tennis courts and country houses in the summer, with tea and cocktails served on the lawn. In the winter issues there should be mountain resorts, cruises bound for Europe, the opera: scenes of warm sitting rooms and dining rooms abound. Just as important as the setting were the characters and the humor that could be born from the relations between them: mother and child, lovers, hostess and guest, borrower and lender, custom- er and counter staff.

The art was not, however, to be without opinion—they sought a unifying editorial vision for the magazine: it was not only about what they wanted to reflect, it was also about what they wanted to ridicule. At the time, things that fell into that category included Rotarians, lecturers, out-of-towners, go-getters, and generally, in Ross’s mind, “everything that is vulgar and dull.”17 But important nuance needed to be struck even in the lampooning of such types: the art should be “satirical without being bitter or person- al.” To reach outside his Round Table sphere, Ross posted help-wanted notices on bulletin boards—specifically seeking contributions about life in New York to the magazine. Finding writing talent had come easy enough with a swath of gifted friends to choose from, but without knowing much about cartooning, he needed a proper recruitment drive. To give Irvin an idea of what he wanted, Ross flipped through various humor publications of the time and pointed out what worked and what didn’t, in his opinion, and who to reach out to for contributions.

This spot illustration was Shermund’s first non-cover contribution to The New Yorker, and appeared in the October 3, 1925 issue.

This spot illustration was Shermund’s first non-cover contribution to The New Yorker, and appeared in the October 3, 1925 issue.Most of the art throughout the rest of the magazine was spot illustrations, department heads, and humorous caricatures. There was a steady dedication to “illustrated jokes”—not quite cartoons, but a plain picture with an explanation below. Al Frueh was one of the few who got it. He was a veteran newspaper cartoonist (first for The St. Louis Dispatch and then The World), and he had an innate grasp of what Ross was going for—a localized, intrinsic humor—clever and intelligent, but not asking so much of the reader as to perplex.18 With the exception of Frueh, few cartoons in the early issues inspired more than a smirk. More importantly, few qualified as uniquely metropolitan, and one could imagine them running in countless other publications. The stylized illustrations and caricatures of Miguel Covarrubias and Ralph Barton decorated accompanying prose but did not carry much heft of their own. Herb Roth, another transplant from San Francisco but about a decade before Barbara, may have piquedRoss’s interest because of his 1913 newspaper strip Oh, That New York!, for The New York World, but here the jokes fell short, and were more situated from the perspective of an exasperated tourist. Other early contributors included Gus Mager, Reginald Marsh, Hans Stengel, Isidore Klein, Peter Arno, James Daugherty, Gardner Rea, and Ross’s childhood friend John Held Jr. Many were aspiring painters, and captions sat awkwardly below their brushwork. Many were British, or German, Cuban, or Mexican. Nearly all were men.

Women were, however, there from the start. Though their numbers were few, there was a female influence on staff and behind the articles and artwork. Katharine Angell (later Katharine White) impacted the magazine’s contents significantly, in addition to Jane Grant. She was hired as an editor early on. As is the case for the staff of most new ventures, she wore various hats and attended the weekly art meetings.19 The first art contribution by a female creator appeared in the premier issue on February 21, 1925—a captioned cartoon by Ethel Plummer—a mildly amusing play-on-words gag between a flapper and her uncle observing a poster for Wages of Sin. Plummer’s drawings were typical for the time—loose and sketchy, reminiscent of the Dana Gibson illustration style. Soon after, on April 4, 1925, the first cover contribution by a woman artist appeared—a scene of city buildings by Hungarian-born Ilonka Karasz, who would eventually contribute more than one-hundred-and-eighty covers to the magazine in her lifetime. This was followed shortly by a May 2, 1925 cover by the lesser-known Margaret SchloemannFrisch. A steady sprinkling of other cartoons by women contributors followed, most famously Helen Hokinson—beloved by Ross— and Alice Harvey. Hokinson and Harvey would become two of the most prolific of the early New Yorker years, and other contributing women artists in that inaugural year included Peggy Bacon, Nora Benjamin, and Nancy Fay.

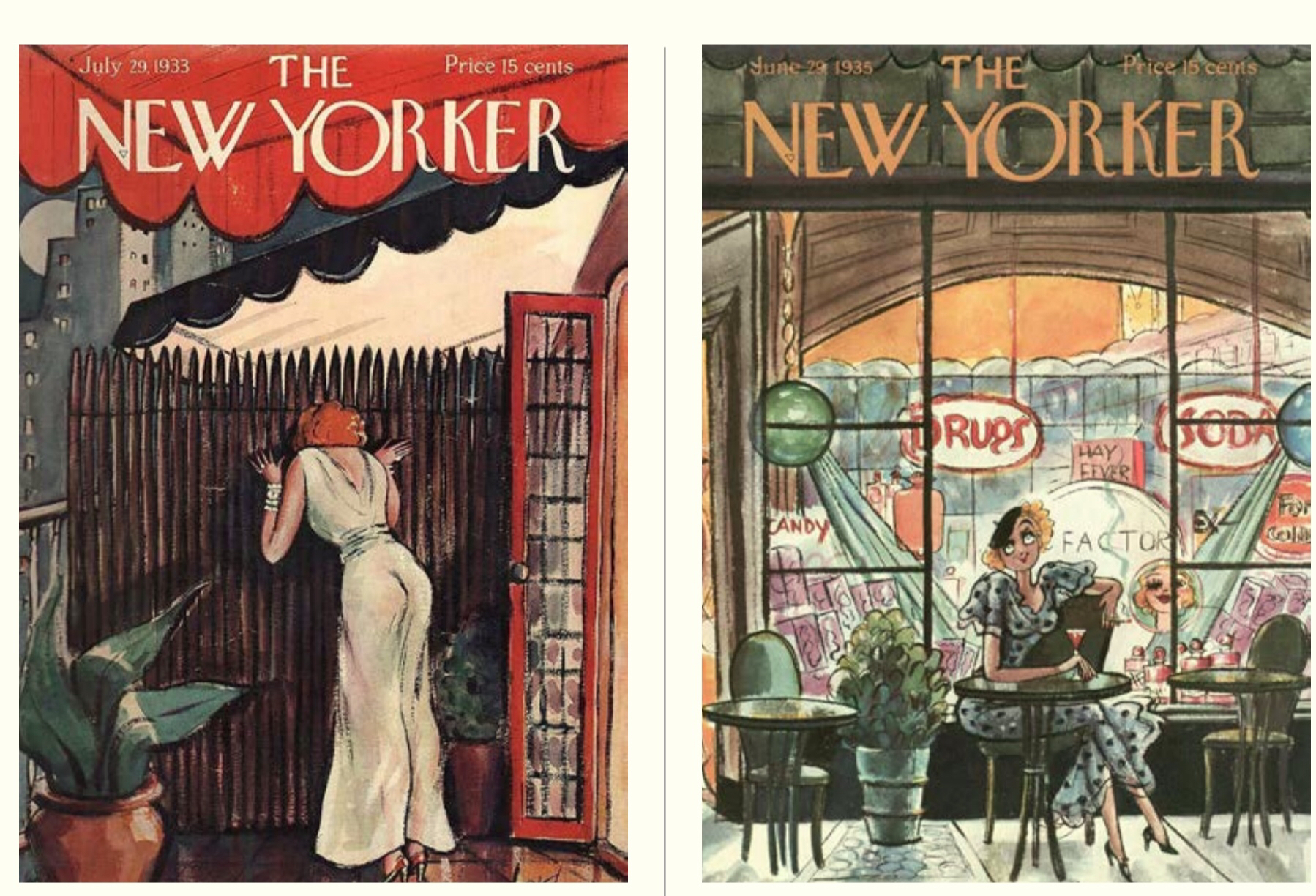

On June 13, 1925, the seventeenth issue, Shermund became the third woman artist whose work made it onto the magazine’s cover—her debut contribution. This first cover by Shermund depicts an alluring but unaffected woman in profile, riding, perhaps down Fifth Avenue, atop an open-air motor bus on a starry night. Her hair, untethered by hats or pins, flows in the night air behind her, and her arm is slung casually over the side of the guard rail as she eyes the city below. It is a perfect cover for capturing Ross’s vision: the young woman is confidently poised, with stylish but not gaudy or overtly wealthy dress, and looks down upon the street below with an air of sophistication and judgment... all while riding public transit. Barbara would experiment with her signature for quite some time. And in this piece, as well as a few others, she seemed to be mimicking Margaret Schloemann’s block “MS” signature with her similarly structured “BS” block letters. Her art appears on the cover again a few months later, on October 3, 1925. This second cover by Shermund also depicts a woman in profile, one who appears to be a nightclub performer, playing cymbals, and adorned with wine grapes for earrings and leaves woven into her hair—described by Judith Yaross Lee as a “female Bacchus.” Both covers employ thick lines and a simple three- or four-color palette of deeply saturated flat colors with an art deco design. It is fitting that Shermund’s first subjects for the magazine were young women: these types would become emblematic of her best work.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Draft of unpublished cover for The New Yorker, c. 1935. Courtesy of Chris Meyer and Rose O’Connor-Meyer Collection. Draft of unpublished cover from The New Yorker c. 1935. Courtesy of Brian Coppola. Published cover art for The New Yorker, March 18, 1939. Draft of cover for The New Yorker, March 18 1939. From the International Museum of Cartoon Art Collection at The Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Draft of unpublished cover for The New Yorker, c. 1935. Courtesy of Chris Meyer and Rose O’Connor-Meyer Collection. Draft of unpublished cover from The New Yorker c. 1935. Courtesy of Brian Coppola. Published cover art for The New Yorker, March 18, 1939. Draft of cover for The New Yorker, March 18 1939. From the International Museum of Cartoon Art Collection at The Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. LEFT: Cover for The New Yorker, July 29, 1933. RIGHT: Cover for The New Yorker, June 29, 1935.

LEFT: Cover for The New Yorker, July 29, 1933. RIGHT: Cover for The New Yorker, June 29, 1935. Cover for The New Yorker, June 8, 1940.

Cover for The New Yorker, June 8, 1940.Whether it was by way of an introduction from Neill Compton Wilson, word of mouth about the new magazine, or other- wise, within a year of moving to Manhattan, Barbara was sending submissions into The New Yorker, possibly via post at first. According to stories passed down by the relatives of Nina Cool and Charles Matthey (Barbara’s maternal aunt and uncle), she hid her gender from the editors and took them by surprise, at least at the start. As family legend has it, after receiving some submis- sions they liked, in hopes of solidifying a relationship with the artist behind them, one of the editors paid a visit to the return address listed on the envelope. “We’d like to speak to Shermund,” they said when the small, shy, round-faced young woman answered the door. “I’m Shermund,” replied Barbara. “No, we’re looking for Shermund, the cartoonist,” they reiterated.

Regardless of their rumored surprise over her gender, the editors made quick work of getting Shermund established at the magazine. The presence and influence of Jane Grant and Katharine Angell undoubtedly helped create space for Shermund’s work at The New Yorker. While Grant was not working directly with her, Ross would not have had the sensibility to publish work like Shermund’s without Grant’s influence on the tone and taste of the magazine (as well as his personal politics). By the end of the magazine’s inaugural year—and for the next two decades to come— Shermund’s work appeared regularly in the magazine in five categories: cover art, spot illustrations, department (or section) header illustrations, captioned cartoons, and advertisements. Her distinct style was woven through nearly every issue during the most crucial years of establishing and securing the magazine’s look and reputation and is inextricable from its foundational aesthetic.

TOP: Early spot illustration for The New Yorker, November 14, 1925. BOTTOM: Early spot illustration for The New Yorker, December 5, 1925.

TOP: Early spot illustration for The New Yorker, November 14, 1925. BOTTOM: Early spot illustration for The New Yorker, December 5, 1925.Shermund’s first contribution to the interior pages of the magazine appeared in the same issue as her second cover, October 3, 1925. For that issue and those that followed in the next few months, she contributed striking graphic spot illustrations placed randomly throughout the magazine and distinctly themed imagery to accompany department headings. Spot illustration refers to the small, often icon-like images created by artists that would fill a space between articles, inserted by the editor where they needed to complete the spacing for the page layout. Each early illustration depicted silent scenes of finely dressed men and women with elegant, elongated bodies and heavily lidded eyes, moving through dimly lit rooms, frequently in furs, or whispering in social groups. They were elevated to accompany department headings by the following month, first for “Tables for Two”— the magazine’s restaurant section—and then for “On and Off the Avenue,” the style section. Shermund’s department head illustrations and spot drawings are iconic and immediately identifiable, and they helped set the visual style for the magazine. They borrow from her art school training at CSFA and can be taken for engravings or linocuts but are all brush, dip pen, and ink. These stark black- and-white images were sometimes abstract—a series of wiggles or angular lines forming some aesthetic appeal, occasionally almost hieroglyphic in appearance. Others had a distinct subject: swimmers, lions, a couple dancing, or audience members. They straddle a line between art deco and tribal art, and it is in their regular repetition that a reader could absorb the specific aesthetic brand unique to The New Yorker.

Department head illustrations refers to the thematic illustrations that ran along with specific repeated sections of the magazine—small panels that served as little windows into the feel of what the section would be about. Shermund created dozens of these, used over the course of decades. Some were square, while others were long, horizontally oriented designs that sandwiched the section title. Shermund’s most enduring designs for department heads were for “On and Off the Avenue,” “Goings on About Town,” “Current Cinema,” “Tables for Two,” “Musical Events,” and “Recent Books.” Others that repeat less frequent- lyacross the decades include: “The Race Track,” “Football,” “Restaurants,” “About the House,” “Popular Records,” “As To Men,” “Tennis Courts,” “Motors,” “Art Galleries,” and “This and That.” Like gargoyles on old city buildings, these drawings are tiny arche- types for the magazine’s sensibility. They are bold, enigmatic, and a little joyful. These section and spot illustrations were reprinted from issue to issue, hundreds upon hundreds of times, over her two decades with The New Yorker. When accounted for in addition to her cartoons, they render her presence in the magazine to over 1,000 appearances.

Goings On About Town spot illustration for The New Yorker, July 18, 1931. From

Goings On About Town spot illustration for The New Yorker, July 18, 1931. Fromthe International Museum of Cartoon Art Collection at The Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum.

TOP TO BOTTOM: Shermund’s spot illustration for E.B. White’s poem, “A Library Lion Speaks” from The New Yorker, January 8, 1927. Courtesy of Chris Myer & Rose O’Connor-Myer Collection. The New Yorker, March 27, 1926. The New Yorker, May 15, 1926.

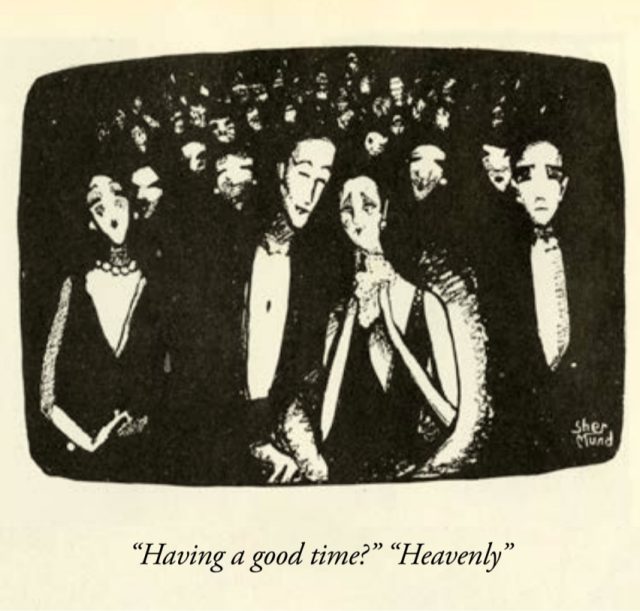

TOP TO BOTTOM: Shermund’s spot illustration for E.B. White’s poem, “A Library Lion Speaks” from The New Yorker, January 8, 1927. Courtesy of Chris Myer & Rose O’Connor-Myer Collection. The New Yorker, March 27, 1926. The New Yorker, May 15, 1926.After three months of contributing these small, iconic drawings to the magazine, the editors had to nudge Shermund to start “adding lines”—as in writing captions—to the art she was submitting. After all, she had not set out to be a cartoonist. But the imagery they had seen from her so far had potential—the rooms felt like rooms you could be in, the people felt like types you might know. With a little effort and the right phrasing, they could be more than a picture; they could be a scene. While she clearly had a knack for creating purely decorative illustrations when the occasion called for it, her line-work had a sense of wit and humor that signaled her potential to do something more. Plus, the nascent magazine was hungry for content and new talent. Shermund’s first captioned cartoon for the magazine appeared on January 16, 1926, and perfectly demonstrates this transition from illustration to cartoon. The image depicts a couple in a dark theater, viewed from thestage. The faces next to and around them fade into the background: attention is on the man and woman in the center front row. She dabs her eyes while her date asks, “Having a good time?” “Heavenly,” she responds, tears in her eyes and the slightest smile on her face. Without a caption, this image could have run just as easily as a department head for Current Cinema, for example. But what we see in it is Shermund developing a sense for that alchemical union between caption and image and a growing understanding of the language of cartooning—the beauty of boiling lines and text down to their simplest forms to deliver an emotional visual impact—and the pleasure of blending words and pictures together to create meaningful contrast.

This gradual easing into the form followed suit for her next few cartoon contributions. In the March 27, 1926 issue, her third captioned cartoon appeared—another quiet image of two finely dressed women in an art gallery, looking upon a large still life painting. The drawing itself does not have anything particularly comedic about it. But the caption, “My dear! It’s eggplant! I simply loathe it, don’t you?” leaves the viewer to wonder whether the question applies to the vegetable or the art and what exactly these two know about the latter. This is a perfect example of the liminal state her earliest cartoons straddled: with the caption removed, they repurposed that exact image for a department head for Art Galleries. The same repurposing would occur with another early cartoon of hers that appeared on May 5, 1926 (“Yeah, the air’s grand.”). Usually in the form of paste-ups of previously published work, editors kept scrapbooks of the artist’s contributions.7 They likely determined these cartoons could speak for themselves without the caption when they needed to fill layout space in a pinch.

By spring of 1926, she had found her footing as a cartoonist. In two of her contributions that season, which appeared on April 3 and May 29, Shermund’s distinct voice emerges—as does what would become the most enduring attitude of her art. In April, she first approaches what cartoonist and historian Liza Donnelly has described as a core principle of her work: “Shermund’s women did not need men.” A couple sit in the back of a carriage on their way home from an evening out. With a look of startled concern on his face, the man leans toward his companion, asking, “Huh! Well, what do I mean to you, any- way?” The woman, legs casually crossed and a sly smirk on her face, replies, “Oh—just an experience.” She has fully embodied Donnelly’s description come late May: two young women gab at a soda shop. One nonchalantly comments, “Well, of course, I do say I’ll never marry. But somehow, I’ve always wanted to be a widow.” From here, throughout the next decade, Shermund’s sharp and perceptive humor penetrates almost every issue. In 1927 alone, her drawings appeared over one-hundred and forty times in the magazine—from mast- heads to spot illustrations to some of her best cartoon work yet. Shermund’s work often appears multiple times per issue during these fertile years. Three captioned cartoons by Shermund appeared in the October 15, 1927 issue, a rarity which occurred again on December 1, 1928, and a testament to how valued and essential her work was to the magazine at the time. A week later, on December 8, 1928 between cartoons, illustrations, and section headings, her work appeared seven times in a single issue.

January 16, 1926. Shermund's first captioned cartoon for The New Yorker

January 16, 1926. Shermund's first captioned cartoon for The New YorkerWhen Shermund first began “adding lines” below her cartoons at the encourage- ment of the editors, she was finding her own voice in the process. That voice turned out to be an incredibly sharp and clever one: a fresh feminist perspective that was new to the magazine. She took common situations—even common conversations and characters—and tapped into that impossible-to-describe magic of observational humor that manages to expose some absurdity, foolhardiness, or unseen sentiment within the moment. Something explosive occurs when the perfect medley forms between an image and its caption; if separated, they’re completely benign. This relies on a risky level of subtlety, a recipe which, if not followed precisely, results in something quite inedible. Many of Shermund’s con- temporaries fell back on specific-and-repeated humorous character types or leaned into absurdism, creating imagery drawn in a way that automatically reads as silly or curious. This is a far more direct route for creating a cartoon, as there’s automatically something at which to laugh or raise an eyebrow. Part of the brilliance of Shermund’s work was that her scenes were not inherently funny— they were normal, real, and believable. They were scenes and situations readers experienced every day. She did not rely on preposterous situations, cheap visual gags, or over-the-top types. And for this reason, it’s easy to imagine why Ross valued her work so much. If asked his eternal question, “could this happen?”—in practically every instance of Shermund’s work, the answer is a resounding yes.

Shermund loved to draw women. There are several distinct themes that run through- out her work, but none as consistently as women talking to each other. In private parlors and bars, at perfume counters or on picnics, Shermund’s women confide in or conspire with each other, gossip or goad, and create scenes in which the reader feels privy to a private conversation. To that end, it comes as no surprise that one of her greatest inspirations was writing and drawing from life—and most of her captions read as bits of overheard conversation between friends, roommates, or family members. While her work may not always pass the Bechdel Test of today, when women discuss male counterparts, it’s most frequently at the latter’s expense. Her affinity for and fascination with how women interact with each other—the way they reveal themselves in the company of close friends, or lament life’s petty problems in operatic terms—is apparent. Often, her car- toons seem to serve up a dose of drama and ask, does any of this really matter? She delighted in contrasts: pitting the perspectives of youth and age against each other, a shy shopper and a brassy saleswoman, a clueless rich collector and the starving artist they admire. If someone took themselves—their troubles, their dreams, their tastes—too seriously, they made for the perfect subject. More often than not, the humor of Shermund’s work is in the sense of a shared experience of shock or amusement reflected in the face of whatever character is on the receiving end of her narrator’s quips. One gets the feeling that they are in on the joke with the other occupants of the scene by way of an inked eyebrow raise or eye roll in place of a real-life elbow nudge. Occasionally, they stare directly out at us, making eye contact with the reader as if to say, “can you believe this?” at life’s little ludicrous moments. In this way, her people bring us into the picture, situating us within a relatable scene. Although her work seemed to laugh hardest at wealthy society-types, she skewered everyone, including the elites, intellectuals, and artists to whom the magazine catered. As Dale Kramer put it in Ross and The New Yorker, “high society would be kidded, but preferably as if from the inside.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·