Tom Shapira | December 2, 2025

I had just finished reviewing Will Eisner: A Comics Biography, not a minute since the final edits, when a passing paperboy shattered my front window with a well-aimed throw. The glass-hurling package contained another comics biography of a famous author, again published by that long-running outfit NBM (still chasing the impossible high of Billie Holliday). Is that their thing right now? Not that I’m against publishers having a thing, but comics biographies don’t seem like such a promising "thing" — not in terms of sales, not in terms of critical praise. Maybe they’re aiming for the library market? As if young folks still rely on Classics Illustrated for a last-minute book report instead of asking Grok and hoping the answer isn’t too racist. Considering my less-than-stellar reaction to the Eisner book, as well as previous non-reviewed biographies from the same outfit, I opened John Muir: To the Heart of Solitude by European writer-artist Lomig (this appears to be their first work in English) with all the caution of a bomb-disposal technician.

It's nice to be pleasantly surprised.

John Muir is a good book. Not a great book. Not a decent book. A good book. We need more of these.

Maybe my reason for enjoyment is that I know little-to-nothing about its subject. It’s possible that for the John Muir-hip the book is full of inaccuracies and misrepresentations. But to me, uninitiated, it works as a story and a presentation of emotional state. Muir is a famous environmentalist and naturalist, co-founder of the Sierra Club and one of the forefathers of nature writing in the United States. All of this I know via the magic of Wikipedia. While there are dry details in John Muir they are saved for the end of the book, after the comics section is already over. The meat of this text is not a biography in the traditional (read: dull) sense. We don’t have early life, we don’t have rise and fall, we don’t have death, we don’t have the obligatory "his influence is felt today" postscript. What we do have is a description of two long journeys Muir took across North America (not just the U.S.), trying to find a direction after an industrial accident makes him reconsider a life as mechanical engineer.

This is a good choice. A comics writer-artist like Lomig is probably not going to be able to compete in terms of pure research with more established biographers. Even something like Tom Scioli’s Jack Kirby biography, which is annotated to the gills, is all based on previous works – no new revelations from archives or interviews to be found. Instead of ending up with a cliff-notes version of a person in an attempt to present a full life, Lomig picks a particularly important moment, the long journey that tuned Muir’s life around, and expands upon it. A tiny rock which, when looked at via microscope, becomes a reflection of the mountain that holds it.

The early chapters of the book are not very promising. A talky, COD psychology introduction that exists to give a definitive explanation for the "why" of John Muir: he worked with machines and machines wounded him so now he goes to nature. That’s less of a personal insight and more of a supervillain origin story. Likewise, the various flashback scenes to Muir’s difficult upbringing, a stern father who worships work the way other men worship God, add little to our understanding of Muir. Or rather, they simplify our understanding to such a degree they might as well not exist. Muir’s father in these scenes is not a person but a cartoon, and thus Muir himself becomes a cartoon counterbalance. An illusion of personal depth on both ends.

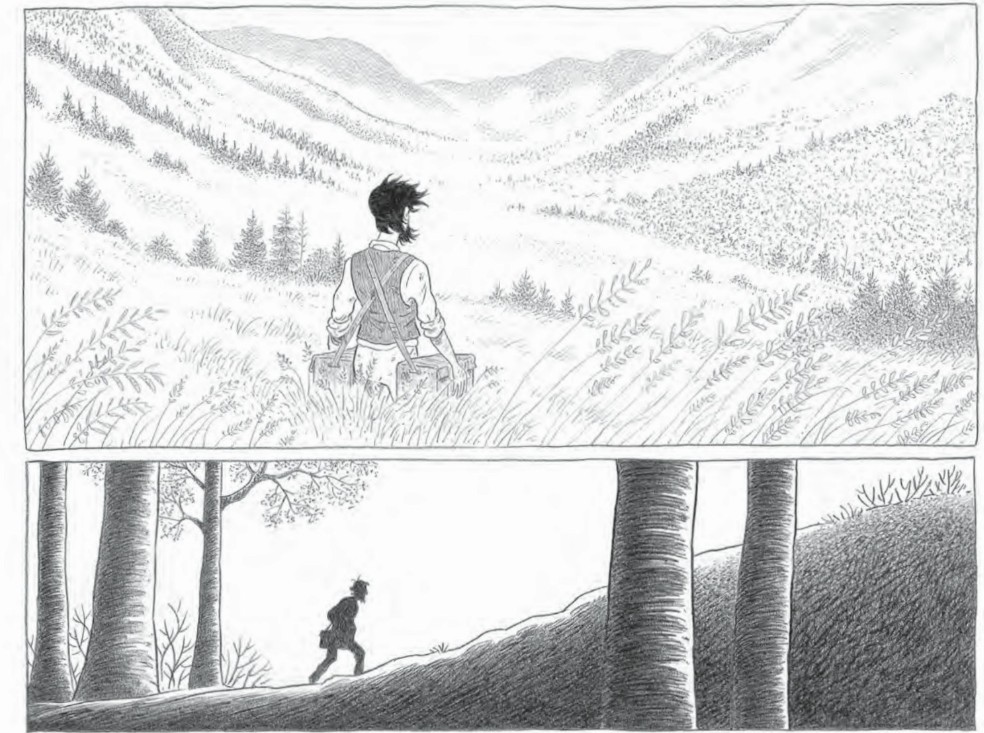

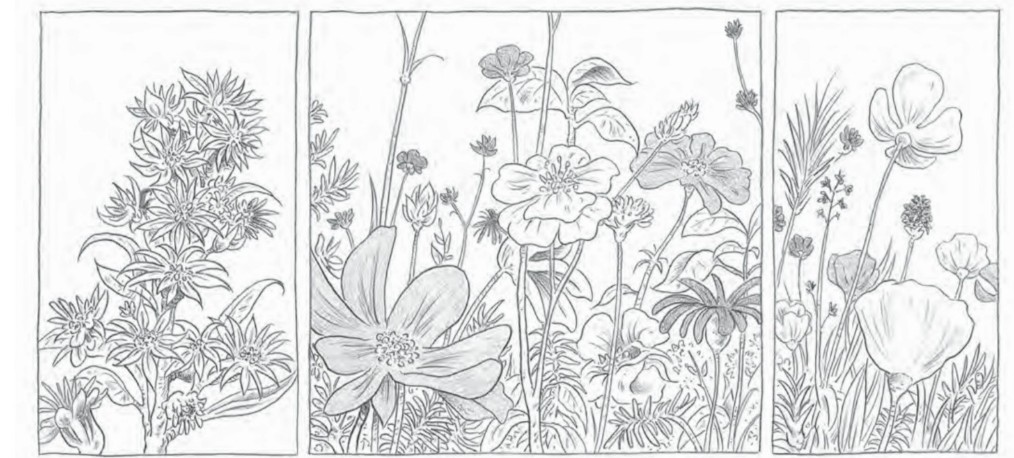

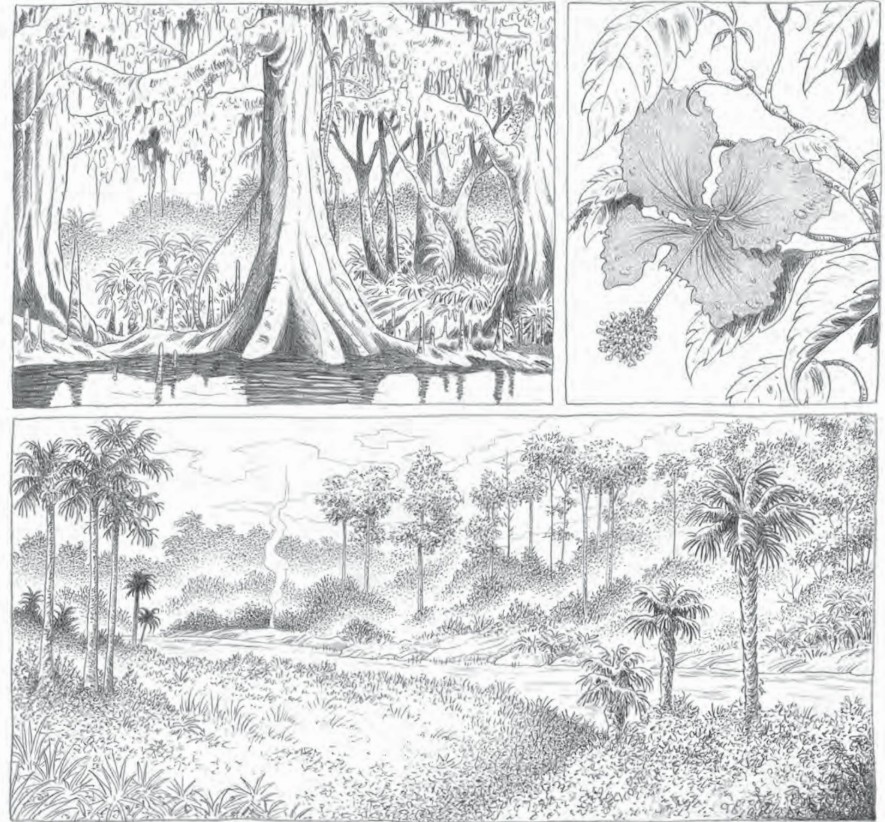

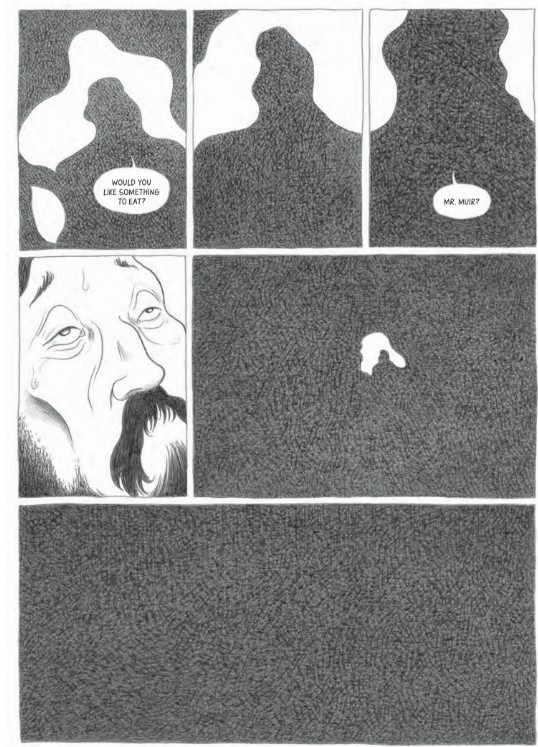

Thankfully, once the book finishes establishing character and goes out into the wilds it improves by leaps and bounds. Lomig’s art truly captures that sense of venturing into nature after spending long periods of one's life in cramped urban spaces. The openness and vividness of these nature scenes is the main draw of the book and Lomig finds exactly the right balance between cartoonish simplification and detailing the flowers, trees, etc. When Muir spends a silent page walking up a ridge before looking up in wonderment at the beauty of the surrounding regions the scene has the potential for cliché, but one must acknowledge that sometimes nature is simple in its beauty and beautiful in its simplicity.

Simplicity is a core theme throughout John Muir. While later journeys (and autobiographical writing) by the man would probably be more goal-oriented, with his self-identity as a naturalist established. John Muir shows a person still in search of himself. He is content to observe people and nature, instead of passing judgment, or trying to sway the reader into a particular point of view (other than his love of natural views).

John Muir is a book of joy. And while the cynic in me thinks Lomig adopts Muir’s sentimental and loving gaze of nature a bit too much, a biographer should never admire their subject too much to lose the critical gaze, I understand being swept up by Muir's philosophy. As a biography, an examination of a man’s life, John Muir fails. As an adaptation, a gaze into the world through another person’s point of view, it is a massive success.

Wanting to read Muir’s books was just the first sign of Lomig’s triumph here. The first thing I am going to do after the review is finished, assuming the paperboy isn’t threatening me with broken windows, is to close this computer, step outside and just start walking. I’ll probably turn back sooner rather than later, but maybe I’ll see something new and beautiful along the way.

***

![Ghost of Yōtei First Impressions [Spoiler Free]](https://attackongeek.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Ghost-of-Yotei.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·