I've been thinking a lot about where exactly new superheroes come from over the course of the last few months, thanks largely to some of the books I've been reading: Annie Hunter Eriksen and Lee Gatlin's picture book biographies of Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, Douglas Wolk's All Of The Marvels and the late Lou Mougin's Secondary Superheroes of Golden Age Comics. I've also been thinking about the subject because of what I've been blogging about lately, like the Thunderbolts* movie, with its cast of characters created by almost 25 writers and artists over the course of some seven decades, and, of course, the related issue of who, exactly, created The Sentry and how.

Mougin's book, an exhaustive survey of Golden Age super-comics, rounds up the scores of characters created by over a dozen different publishers in the years following the first appearances of Joel Siegel and Joe Shuster's Superman comics (and some of the more distinct characters to follow in his immediate wake, like Batman, Wonder Woman, The Human Torch and Captain America).

Given the pace at which this army of superheroes appeared and then disappeared from the pages of the comic books of the time, one imagines that most were created on-the-fly by the guys who wrote and/or drew them.

When a modern reader thinks of how someone might have got the idea for a Cat-Man or a Crimebuster, a Wizard or a Boy King, a Daredevil or a Black Hood, a Mother Hubbard or The Face, it's easy to imagine that sort of out-of-the-blue, lightning bolt-style of inspiration, a deadline-driven act of creation that rushed from an image in someone's head to the drawing board to the printed page (For the more unique characters, anyway; a lot of these heroes seemed to come from artists doing their own riffs on a Superman, or trying a different animal theme for a Batman, or rearranging the stars and stripes on a costume to get their own Captain America).

As for the heroes of later generations, though?

Well, they had these Golden Agers (and their peers from the pulps and radio and film serials and comic strips) as a vast reservoir of inspiration. Not only could later creators find various templates among the biggest successes of those early years who are still starring in their own comic books today (Superman, Batman, Captain America, etc), but also the heroes I would consider the true second stringers (the characters who ended up on the JSA, for example, and those of publishers Fawcett, Quality and maybe MLJ). And then the more random-sounding also-rans that fill Mougin's book, like White Streak or The Conqueror or The Blue Bolt or Magno or the guys named The Reckoner, of whom there was more than one.

Many of the later heroes of the late 1950s and 1960s created for DC and Marvel and Charlton and others could be traced back to Golden Age ancestors, and contemplating such second-generation heroes now, it's actually kind of hard to think of a character whose name, power or gimmick doesn't have Golden Age antecedents of some sort. (Seriously, try it!)

But still, there are some. Jack Kirby and Stan Lee's The Thing, for example, seems to be born more of monster comics than old superhero comics, and wow, where did the idea for the Silver Surfer come from exactly, you know?

Anyway, some bits of Wolk's book that I found particularly interesting were the examples he gives when discussing the creation of certain characters.

In the weeks since I read All of the Marvels, these examples seemed to only become more resonant, as I thought about Lee's work with Kirby and Ditko on the first wave of Marvel heroes while reading those picture books and then later reading of the avalanche of superheroes of the 1940s in Mougin's book.

Very early in Wolk's book—page 5, actually—he mentions that the "Marvel's narrative," the focus of his book, "has a peculiar relationship with his authorship":

This passage then leads to an extensive footnote, during which he notes the difficulties involved in untangling who created what.

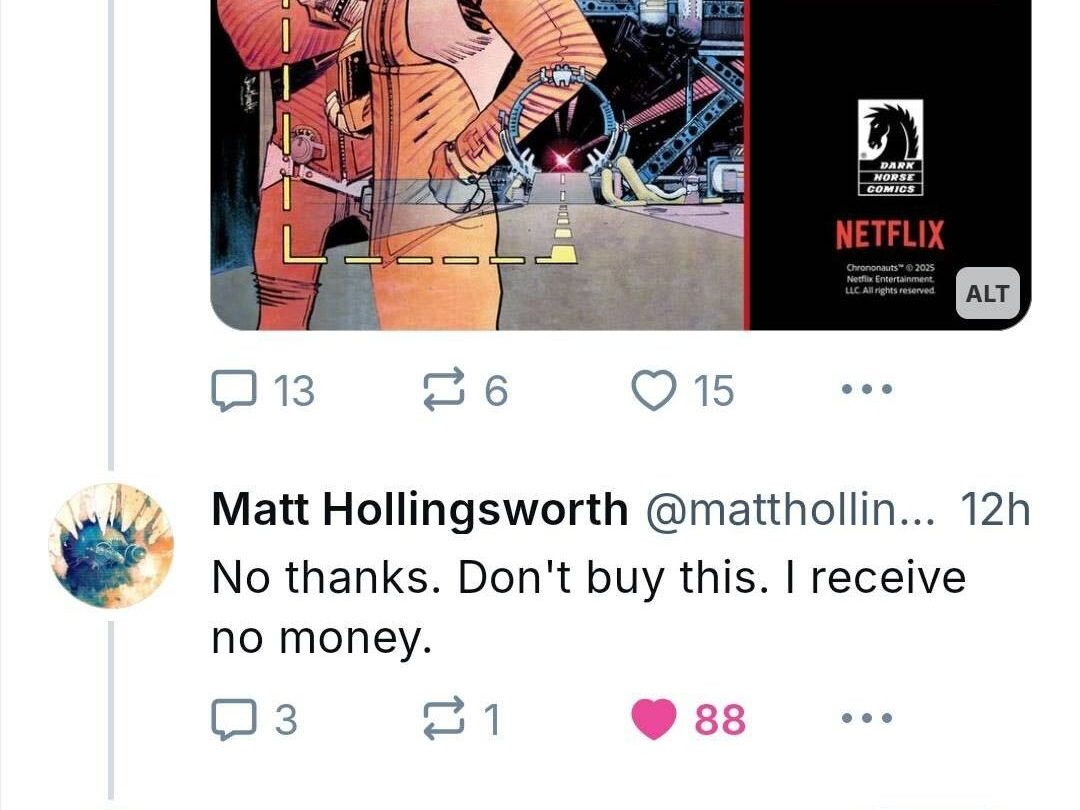

This can obviously be a contentious subject that fans and sometimes the creators themselves have argued about over the decades, be it how much (or even if) Stan Lee might have contributed to those early Marvel heroes with his collaborators Kirby and Ditko, or the later disagreements regarding the creation of Wolverine and Ghost Rider (the latter of which went to court), or the current issues with The Sentry.

Wolk writes:

He goes on to cite a few other relatively easier ones, like Captain America (Kirby and Joe Simon) and Doctor Strange (Ditko), before showing how quickly it can get rather convoluted.

Iron Man? That's a little trickier. Lee plotted his first story, but Larry Lieber wrote its dialogue; Kirby drew the first cover and designed the character's initial costume (which barely resembles the familiar rend-and-gold one, designed by Ditko a bit later); Don Heck drew the initial story and invented what its protagonists Tony Stark and Pepper Potts look like.So the Marvel Universe hadn't even been around a year yet, and there was already a character who seemed to have at least four primary creators, whom Wikipedia lists under "created by" in its article on Iron Man. (As for Ditko, who Wikipedia does not cite as a creator of the character, where does he fit in? Is a redesign considered an act of creation? If it comes some time after a character's debut, is it seen as somehow less important? Does it matter if that redesign becomes the primary, default one?)

The next example is more complicated still. Writes Wolk;

Wolk doesn't mention it at all here (this is just a footnote, long as it is, of course, and this is outside the purview of his book), but it's worth noting that Marvel's Daredevil, who debuted in 1964, was preceded by another comic book hero named Daredevil from an entirely different publisher.

The two-toned, boomerang-wielding Daredevil of Lev Gleason Publications, whose creation is credited to Jack Binder and Don Rico, debuted in a 1941 issue of Silver Streak and his own title ran 134 issues, not being canceled until 1956. (This is the character who, long since lapsed into the public domain, one might have seen more recently in the pages of Savage Dragon as "The Dynamic Daredevil" or in various Dynamite Comics as "The Death-Defying 'Devil".)

Mougin does mention the possible relationship between Lev Gleason's Daredevil and Marvel's Daredevil in his book:

Does that not sound plausible to you? If not, well, Mougin did say "legend", didn't he? (I am curious about his mention of Ditko here, as Wolk doesn't mention Ditko at all when he discusses the creation of Marvel's Daredevil.)

The sense I got while reading this very early bit of Wolk's book was that rather than being created by a single artist or a single writer or even a single writer/artists team, sometimes it's more of a group effort, a creation by committee. That certainly seems to been the case with Iron Man, for example.

As for the Daredevil example, it shows not only that sometimes it's a team or a staff (or, in Marvel's case, a bullpen) that might create a superhero character, but sometimes it can take multiple creative teams and multiple years—hell, here some 20 years!—before a corporate character like Marvel's Daredevil reaches what will ultimately be considered his essential, perfected form.

Far later in the book, in a chapter entitled "Good is a Thing You Do" that is devoted to the debut and early issues of the current Ms. Marvel Kamala Khan and to Ryan North, Erica Henderson, Derek Charm and company's Unbeatable Squirrel Girl (the latter of which was built around a 1991 character designed and originally drawn by Ditko), Wolk gives an even better example of a character being developed into creation, I think. He does so while also illustrating how newer Marvel characters are dependent on older ones, and how even their earliest antecedents can be traced back to still earlier, pre-Marvel ancestors.

"Kamala Khan is yet another of Marvel's collective creations, her real-world origin too complicated to be attributed to a single originator," Wolk writes.

Wolk also cites the particular creative choices made by colorist Ian Herring and letterer Joe Carmagna as distinct and important, each further defining and differentiating the initial Ms. Marvel comic book series from others in Marvel's line.

We could also note that while McKelvie designed Kamala's costume, a significant component of it, the lightning bolt-shaped symbol, was taken from Dave Cockrum's redesigned costume for the previous Ms. Marvel Carol Danvers dating back to the '70s.

And, of course, the superhero codename "Ms. Marvel" also came from Danvers, who was created, as Danvers, by Roy Thomas and Gene Colan in 1968, but made into the superhero Ms. Marvel by Gerry Conway and John Buscema in 1977.

And, just to make this into a game of superhero telephone, the original Ms. Marvel was a distaff version of the male hero Captain Marvel (created by Stan Lee and Gene Colan in 1967). He took his name from the Golden Age Fawcett Comics character Captain Marvel (created by Bill Parker and C.C. Beck in 1942), and that Captain Marvel was based on Siegel and Shuster's Superman...or at least, the company then known as Detective Comics was sure enough that he was that they took Fawcett to court, accusing them of copyright infringement (The case was eventually settled in 1953, in large part because, in Fawcett's estimation, superhero comics had by then ceased being profitable enough to fight over).

And thus we get from 2014's Ms. Marvel Kamala Khan all the way back to the very first superhero in 1938.

Anyway, both Wolk and Mougin's books are very interesting reads, and ones that should be of interest to anyone who reads superhero comics. I'll be formally reviewing them in the future, but I wanted to touch on this idea of superhero creation as a process of development in a post of its own.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·