J.D. Harlock | December 2, 2025

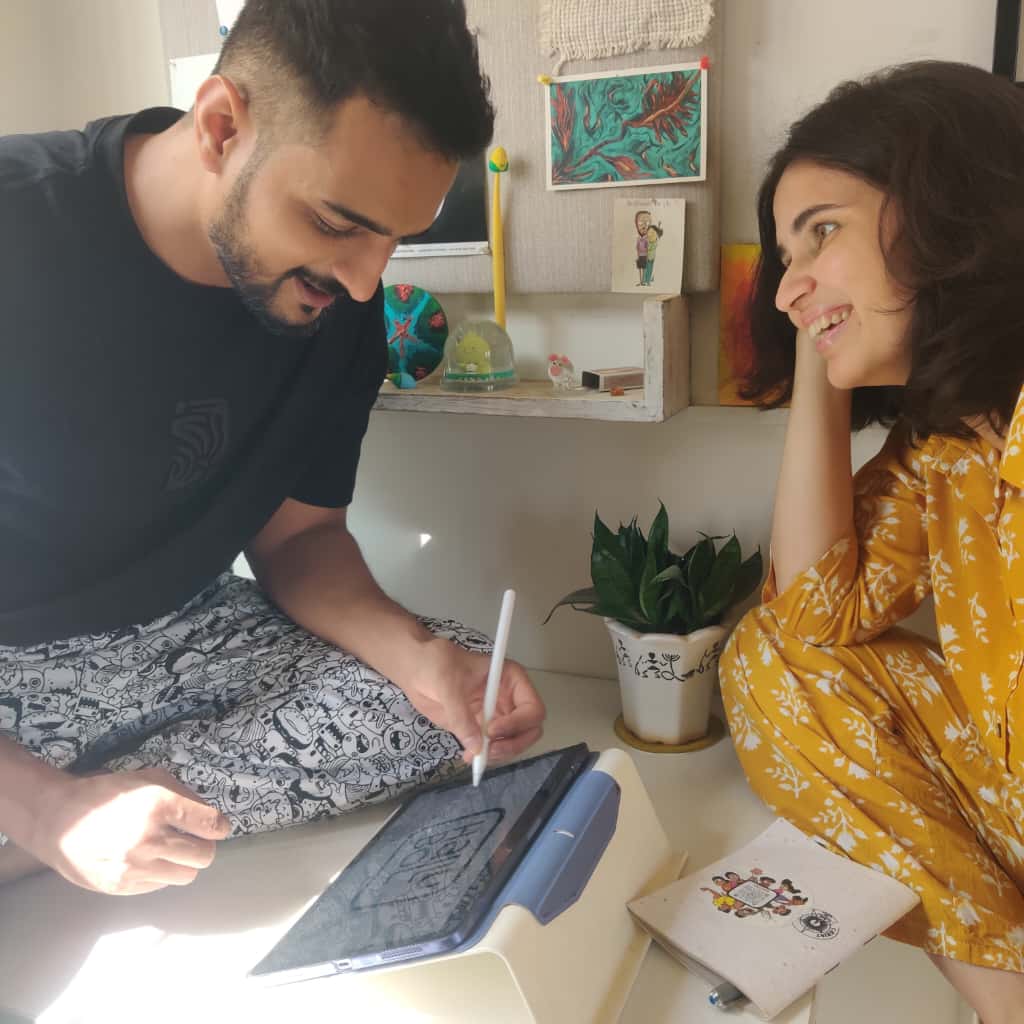

Rahil Mohsin at his home studio in Bangalore. Photo by Shrikant Parab.

Rahil Mohsin at his home studio in Bangalore. Photo by Shrikant Parab.Rahil Mohsin is a cartoonist based in Bangalore who has become a familiar face in the Indian comic book market. With various titles showcased at events like Comic Con India and Indie Comix Fest over the last twelve years, he’s recently made waves in the scene as the co-founder of Hallubol, the world’s first comic book series in Dakhni. Dakhni is an Indo-Aryan language that survives today in South-Central India primarily in spoken form. In addition to promoting collaboration among Dakhni-speaking creators, artists, and musicians, Hallubol aims to preserve and raise awareness about the endangered language, which has historically been marginalized, as well as present an authentic depiction of a community that is often ridiculed in India’s mainstream media. In September 2025, Mohsin kindly agreed to an online interview to discuss his career leading up to Hallubol in-depth. Join us as we dive into the latest creation of one of the most promising rising cartoonists in South Asia.

J. D. HARLOCK: Let’s start at the very beginning. Can you tell us a little bit about your early life?

RAHIL MOHSIN: So I was born in Bangalore back in 1990, and this is where I was brought up. At the time, it was a humble city with a rich history, storied heritage, and magnificent gardens. Every time my father visited us during our summer holidays from his work abroad in Riyadh, we would have the best time. Come evening, he would take us to visit Cubbon Park, where we’d stroll around the greenery, eat some mouth-watering street food, especially roasted corn, while we’d pass some major historical landmarks, which were all within a ten-kilometer radius. This included iconic landmarks such as Chinnaswamy Cricket Stadium, Brigade Road promenade, Manekshaw Parade Ground, and MG Road that still inspire me as an artist to this day.

So what drew you into the exciting world of sequential art?

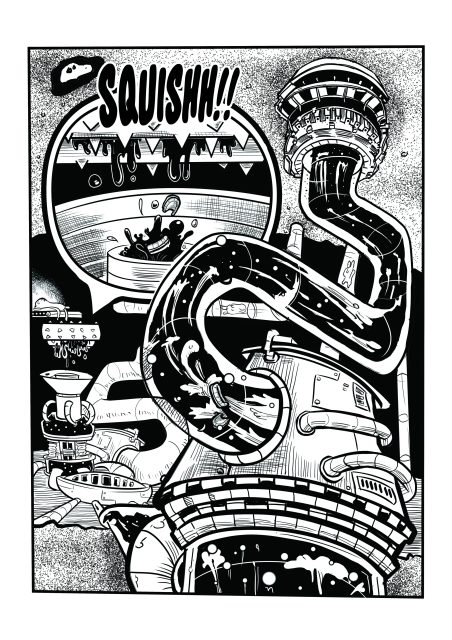

The mighty corpse destroyer unit appearance in Snot published in Inklab #2: Consume.

The mighty corpse destroyer unit appearance in Snot published in Inklab #2: Consume.Abbu, my father, is a bibliophile, and he was the first person to teach me how to read comics. There wasn't a moment in my childhood when I wouldn’t see a tattered novel in his hand. He was a huge fan of John Grisham in the early 1990s, but later moved on to more conservative works, such as Shogun and Jeffrey Archer’s titles. We are now on MG Road, one of the quainter parts of Bangalore’s shopping district. This area was known for providing branded, smuggled, and counterfeit clothes, accessories, electronics, and books. Back in the day, I’d watch Abbu have a spring in his step as he strutted towards sketchy-looking characters here standing at the side of the footpath, selling pirated novels that were sprawled before him on a bedsheet. Every time we visited MG Road, Abbu would take us to comic book shops that hadn’t been flooded by Marvel and DC, but provided a variety of comics — some mythological, some regional, and some set in Indian settings. Many times, Abbu would sneakily buy me an extra comic as a gift for performing well at school, eventually turning me into a curious and avid comic reader. Of course, I would eventually be introduced to American superheroes much later in my teens, but until then, I was hooked on the likes of Indian comics and magazines like Amar Chitra Katha, Wisdom, Children’s Digest, Champak, and Indrajal Comics, to name a few.

And how did you end up learning the craft?

Living through the ever-changing political landscape of South India was not easy, but drawing helped me cope with the anxiety. Much to my parents’ chagrin, I’d spend hours a day copying panels from comics I read into a plain sheet art notebook instead of studying. Eventually, they were forced to allot me a specific time limit to draw each day, depending on how I performed at school, which determined how much drawing time I got. It was sometimes fifteen minutes, an hour, or sometimes none at all. Unconsciously, this prepared me for life as a cartoonist.

What was it that led you to decide on a career in comics?

Initially, I pursued a career in 3D animation. It was a rather unconventional choice for a Dakhni boy from a conservative yet vaguely liberal Muslim family, but then again, I hadn’t really shown an interest in anything else growing up. I’d spend most of my time in our college library, reading books on various animation styles and occasionally browsing the internet for obscure comics to read online. It was during this period that I came across Jhonen Vasquez’s graphic novel series Johnny the Homicidal Maniac. The dark, gothic nature of these underground comics, published by Slave Labor Graphics, captivated me. The striking contrasts and innovative panel layouts were something I’d never seen, and I began studying each panel with great interest, leading me to spend more time doodling little comic strips, almost mimicking Vasquez’s style to help create my first iteration of self-expression borrowed from a Western artist. Unfortunately, my extended hours in the library were not well-received by the school administration, which led to my skipping most of the crucial classes I needed to earn my degree. I, on the other hand, had already decided to ditch the prospects of being an animator to pursue a career in comic-book making instead. Thanks to my time doodling in the library, I’d created a series of crudely drawn black-and-white comics, and having received enough validation from my peers and some encouraging art instructors, I’d developed a sense of certainty that I’d be able to have a career in comics.

For a lot of creators, that leap from knowing that you want to pursue a career in comics to actually pursuing it is a story in itself. How did it come about for you?

Well, it wasn’t long until the administration got whiff of my talent, and thanks to a kind principal, I was the only student to graduate by submitting a comic as my final project. But here’s the catch: I was only awarded enough points to barely pass. Not that it mattered. After graduation, I began doing odd jobs like interning as a storyboard artist at a local animation studio, where I began creating an original comic series, similar to Vasquez’s style, borrowing elements of dark fantasy and American school drama into the storyline. This choice reflected part of the media I’d consumed growing up, which later bled into my professional life, but still, it felt inauthentic. However, it did help me secure some small projects for magazines that I could contribute to. Among them was Teacher’s Plus, an English comic strip series titled Mom, Ma’am and Me. It was a short slice of life where I experimented with a different style, still drawing influences from Vasquez’s style.

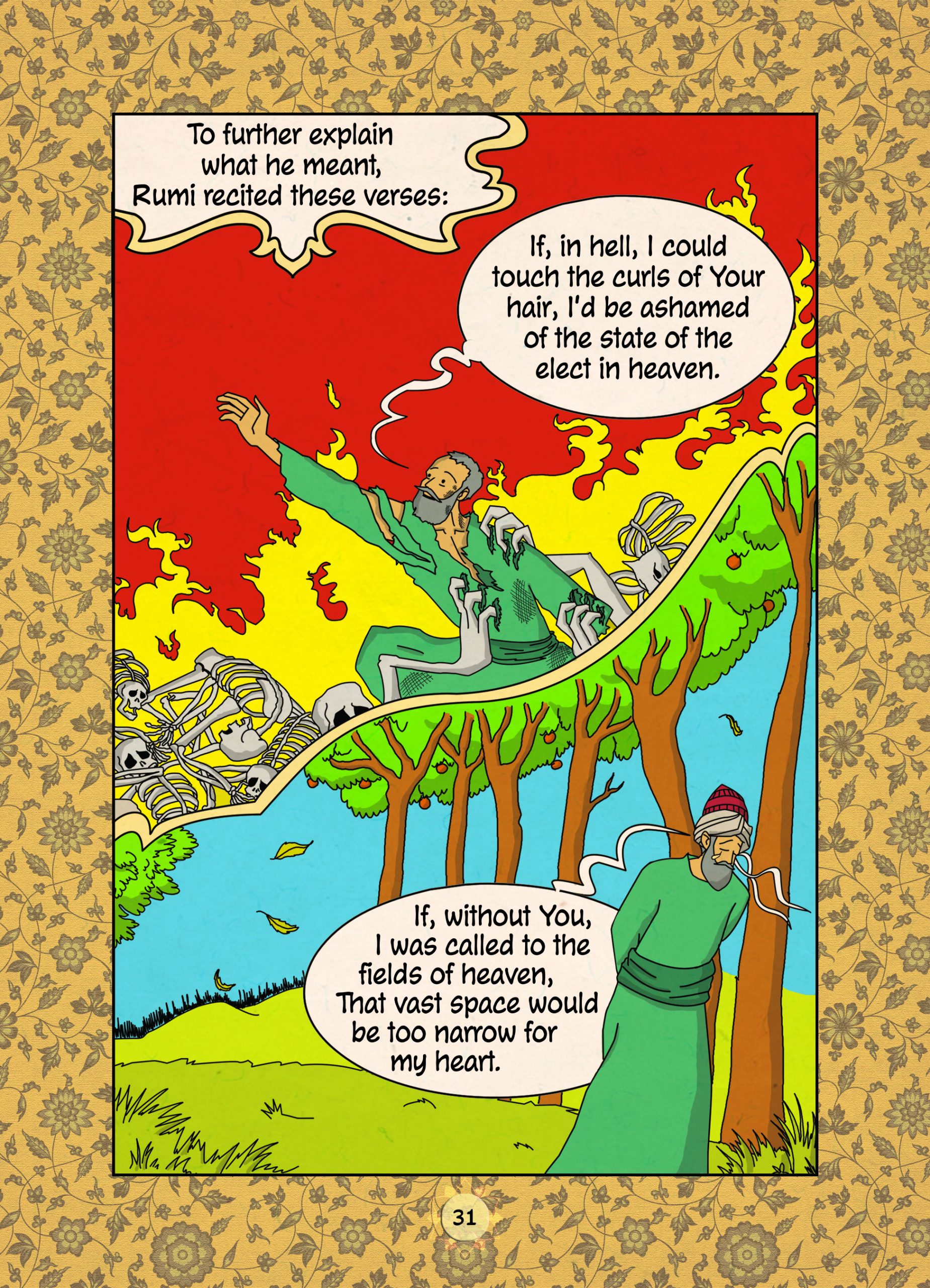

Page from Rumi Vol. 2, Compiled & Edited by Mohammed Ali Vakil, storyboard & art by Rahil Mohsin, color by Mahdi Tabatabaie Yazdi, production by

Page from Rumi Vol. 2, Compiled & Edited by Mohammed Ali Vakil, storyboard & art by Rahil Mohsin, color by Mahdi Tabatabaie Yazdi, production byAbdul Gafur Madinal and calligraphy by Muqtar Ahmed.

Vasquez’s influence is still apparent in your work, but your style has evolved significantly since then, and I’m wondering how that came about as your career progressed in the last decade or so.

Having realized the importance of individual artistic expression, I began amassing graphic novels to further study different styles. I eventually came across Craig Thompson’s Blankets, and I became obsessed with it. Around this time, in 2012, India was beginning to see the emergence of a new comics market. Events like Comic Con India provided a platform for young, up-and-coming creators and fledgling comic book studios to stand shoulder to shoulder with veteran comic publishers, engaging with local audiences in several metropolitan cities. One such publishing house was Sufi Comics, an entrepreneurial venture by two brothers, Arif Vakil and Ali Vakil. Sufi Comics was looking for an artist to work on several of their projects, and I applied with a few personal comics under my belt. Soon, I began working on three graphic novels: The Wise Fool of Baghdad, Rumi Vol. 1, and Vol. 2. The comics created with Sufi Comics serve as collections of illustrated stories and poems, mostly popular in the Middle East. For us, they served as a glimpse into timeless tales of a culture and religion that have been a boogeyman in the post-9/11 era. Given the nature of the stories, I began to adapt my art style to best represent them with as much respect as they deserve.

Having worked on these three graphic novels over a span of four years, I began to feel the stagnation caused by the limitations of my artistic expression and started looking for projects beyond the local landscape. I reached out to like-minded individuals online through Facebook groups populated by people looking to hire artists for commissions.

Driven by a desire to experiment, I've taken on projects from various genres, including horror comic scripts, slice-of-life stories, historical fiction, sci-fi, mythological tales, romantic comedies, and noir. These comics boasted different styles but still differed significantly from their mainstream counterparts. Following two indie titles in collaboration with Andre Mateus, which were The Big Sheep: A Farm Noir and Kiss Kiss Blam Blam: A Killer Date, I began to circuit the Indian comics scene, making appearances at events like Comic Con India and Indie Comix Fest to sell my titles and interact with our core demographic. Along with the above titles, I have also self-published my other works, such as Blame it on Rahil, a collection of my commissioned pieces with various international creators. While these comics helped me establish myself as an artist for hire in the Indian market, with Comics Beat honoring me with the title "artistic chameleon," I lacked a genuine voice that truly reflected me and my authentic self — something that would reflect my background. I’d managed to secure two ongoing comic series as a comic artist for Scout Comics — Catdad & Supermom and Misfitz Clubhouse — helping me pay the bills as much as a freelancer can afford, and by then, I was married to my longtime friend and children’s book author, Alankrita Amaya.

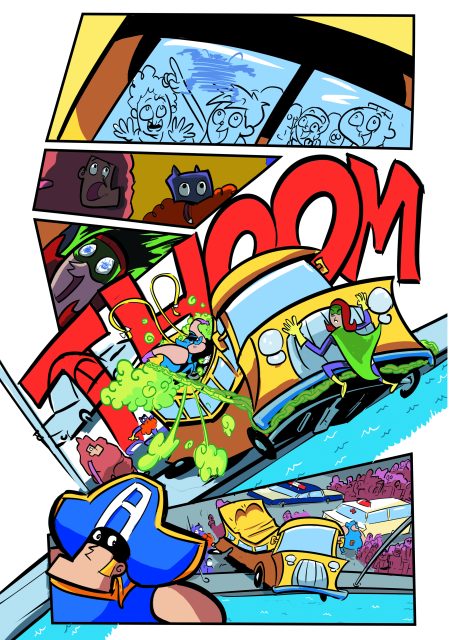

From Catdad and Supermom Issue 2 What Makes a Hero. Story by Robert Gregory and Art by Rahil Mohsin.

From Catdad and Supermom Issue 2 What Makes a Hero. Story by Robert Gregory and Art by Rahil Mohsin.So what sparked your interest in languages?

Bangalore’s multilingual culture helped expose me to several South Indian languages. People we interacted with in our daily lives came from diverse backgrounds, speaking languages such as Tamil, Kannada, and Hindi, which helped us look beyond our linguistic differences and come together to share and celebrate our respective cultures. Thanks to this, I managed to learn English, which we were taught in school, Hindi, a North Indian language, and Kannada, our state language. All the above languages were taught to me in school and were completely different from the cultural background and language I come from, which was Dakhni.

Since English-speaking readers are probably unfamiliar with Dakhni, can you tell us a little about it?

Dakhni speakers are considered a linguistic minority that have yet to receive their due recognition. Having survived mostly as a spoken language for over a century, Dakhni has always been a victim of being claimed and forcibly integrated into more popular languages in India, such as Urdu and Hindi. This unfortunate struggle is just one of the many struggles that everyday Dakhni speakers face. First of all, the language is spoken by mostly working-class Muslims and sometimes Tamil migrants. This is why Dakhni was deemed as a "lower" language in an imaginary hierarchy of languages in India, whose order changes depending on who’s talking. Along with the consistent ridicule in mainstream media, there is sometimes a religious angle to the vitriol against the language by certain politically motivated individuals. Having personally grown up in the community and often being exposed to such mockery, I began to express myself less in my comfortable linguistic expression and started speaking in English to appear less "uneducated." As a result, I grew up code-switching to further myself in the fields I've chosen.

So let’s finally talk about your latest project, Hallubol. Can you tell readers a little bit about it?

So, in 2023, I co-founded Hallubol, the world’s first bilingual Dakhni-English comic series, with my partner, Alankrita Amaya. Dakhni, a marginalized South Indian language often ridiculed in mainstream media, plays a central role in this project. Hallubol reclaims that space by portraying authentic Muslim voices and everyday life in Bangalore, with real-time Dakhni-English translations making the work accessible to wider audiences.

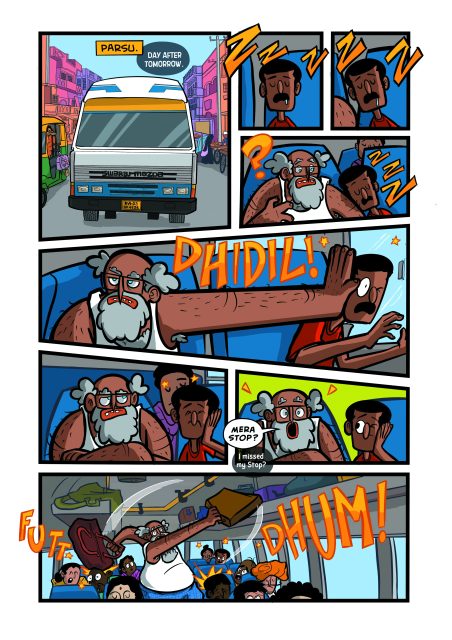

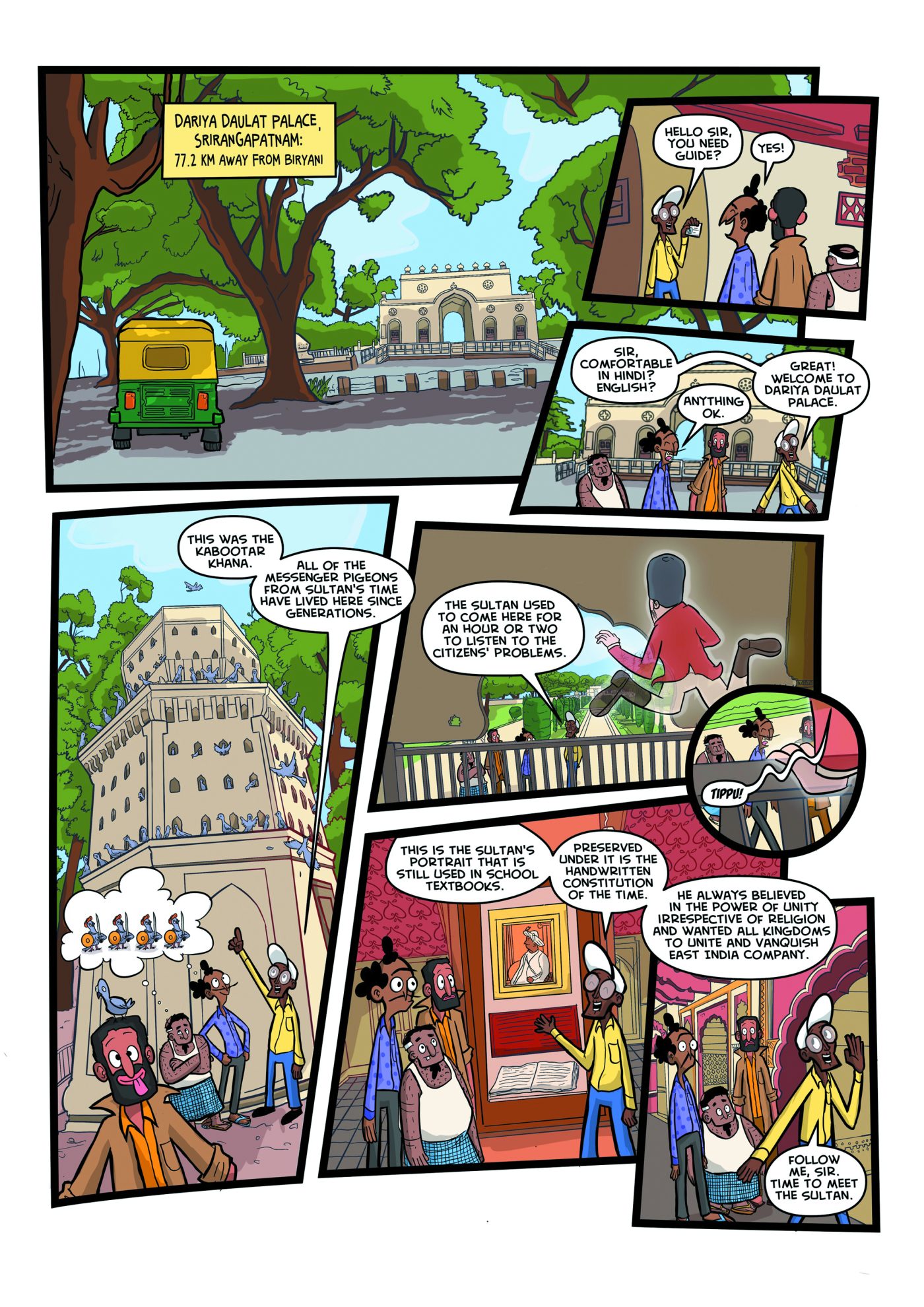

Out of the five-issue arc, two have been published. The first issue, "Mard Bann" (or "Be a Man"), tackles the concepts of toxic masculinity and generational trauma. This introductory issue follows Mansoor, a meek and humble juice seller, who is haunted by a nightmarish floating beard with glowing eyes that demands he “be a man.” Haunted to the point of seeing the beard on everyone’s face, Mansoor struggles to reconcile what it means to “man up” while trying to break free from the confines of societal expectations and generational trauma. The second issue, "Abba Aari" (or "Father’s Visiting"), introduces Abba, the patriarch of the family, who visits Mansoor and his household. The story explores aging patriarchs attempting to maintain control through whatever means necessary. And how the family, along with Mansoor, comes together in solidarity. Apart from these issues, there's an eight-page short comic in Comixense magazine (Volume 5, No. 2) titled "Biryani Khaane Jayinge." It pairs Mansoor with two of his friends as they set out on a road trip around town in search of biryani. Along the way, they encounter a ghost while exploring historical spots throughout their journey.

Crucially, Hallubol does not stop at Dakhni; we also represent other Indian languages and cultures, portraying characters not as stereotypes but as real people. I believe no language exists in isolation, and multilingualism is what sustains coexistence and cultural diversity in the world.

Page from Hallubol #1: Mard Bann. Story and art by Rahil Mohsin and Alankrita Amaya.

Page from Hallubol #1: Mard Bann. Story and art by Rahil Mohsin and Alankrita Amaya.What sparked the idea for Hallubol?

Until 2019, my career trajectory was heading in the direction of being a freelance artist. But when the 2020 pandemic happened, things changed. With less work and more time, I reconnected with my family members, especially my younger cousins with whom I’d shared a wonderful childhood. We reminisced about days spent at our grandparents’ home watching reruns of cartoon shows. Realizing that all through our lives we had consumed entertainment in languages foreign to us, and now that most of my cousins were in their early thirties with families of their own, there was a need to leave behind, or at least pave the way for, some form of literature in our native language, Dakhni.

The idea marinated for a while until Alankrita and I began brainstorming ways to create a comic series in Dakhni. The idea was to make the language accessible to a larger, non-mainstream audience. Therefore, we decided to write the Dakhni dialogues phonetically in English script. Originally, Dakhni used the Persian/Arabic script, but over time, modern youth in Dakhni circles have become comfortable using the Roman script for daily communication and on social media.

We initially planned to create a comic series that would be a vague caricature-ish take on Dakhni life, but we realized that would defeat the purpose. We then began focusing on issues faced in Dakhni society that are almost never portrayed in mainstream media. Our motivation evolved from being just a linguistic awareness comic to a series that also provided social commentary. Now, our books focus on issues surrounding toxic patriarchy, generational trauma, societal expectations, and parental authoritarianism, while blending in concepts of hope, unity, inclusivity, and mutual support. Thus began Hallubol, which translates to Speak Softly, a phrase used in Dakhni circles to avoid being spotted in mixed linguistic groups and ridiculed under suppressed sniggers.

Hallubol founders Rahil and Alankrita doodling at their home studio in Bangalore. Photo by Zoya Noor.

Hallubol founders Rahil and Alankrita doodling at their home studio in Bangalore. Photo by Zoya Noor.It's interesting that you're collaborating with your wife on this. Is this the first time you've worked on something like this?

I’ve known Alankrita since 2008. She’s an award-winning children’s writer and a gifted illustrator with over 30 titles to her name. We had made several attempts in the past, experimenting with media such as stop-motion, picture books, and small comic strips during our college years. However, once our professions diverged, we missed out on the opportunity to collaborate. Although we often shared our work with each other for feedback and valued each other’s opinions, we weren’t able to shape any project that highlighted our strengths until Hallubol happened.

Most of the time, the ideas for each comic flowed seamlessly. I would narrate stories from my childhood, incorporating elements that would better suit the comic medium, and Alankrita would step in to make the story more coherent for non-Dakhni-speaking readers. Alankrita, being a non-Dakhni speaker, understood the audience well. Her experiences with my extended family also led to valuable observations about the culture that are often overlooked by Dakhnis themselves.

What did you draw inspiration from in crafting the series' plots and characters?

Abba misses his stop, from Hallubol #2: Abba Aari. Story and Art by Rahil Mohsin and Alankrita Amaya.

Abba misses his stop, from Hallubol #2: Abba Aari. Story and Art by Rahil Mohsin and Alankrita Amaya.Since I grew up in a Dakhni-speaking household, I was fortunate enough to interact with various colorful characters in the community. On my maternal side of the joint family, each person around me left a lasting impression. We eventually moved out, and I became more of a distant observer of my extended family’s quirks. These experiences served as inspiration for the world I wished to explore in the Hallubol series.

Most of the characters in the Hallubol universe are a mix of unique quirks inspired by real-life people. For example, the buffed-up bodybuilder character, Sattu, is based on my maternal uncles, who were obsessed with working out and following their Bollywood idols, especially Salman Khan. Sattu embodies the characteristics of a wannabe bodybuilder and social media influencer — sometimes naïve but with a heart of gold — which makes him endearing to readers, perhaps reminding them of someone they know, or even a version of themselves at some point in life. The series features a roster of around a dozen characters, each forming the mold of an archetype to further the plot.

Several influences over the years shaped Hallubol’s unique voice. While most of the plot elements are vague recollections of nostalgic memories, with plenty of animated drama and a dash of Dakhni charm, it would be unfair to say that no other projects inspired us. Ensemble casts in media, especially shows like The Office, helped me understand how to give varied characters enough screen time and do them justice. Local shows like Killer Soup helped us explore multilingualism in culturally rich backdrops. Graphic novels such as Habibi, Blankets, Newts, Invader Zim, Lenore, Ratman, and the works of Ian McGinty and Skottie Young inspired our tone and visual language. Nostalgic regional shows I grew up watching on Doordarshan, such as Captain Vyom, Shaktimaan, and Vartmaan, also helped me understand the pacing that our target audience would be comfortable with.

You've chosen to have it in Dakhni and English, rather than other regional languages you're familiar with. Why is that?

English is still a widely read language in India, which is why Dakhni-to-English seemed like a practical step for us. Our vision was to tap into a niche space, and so far, our books have made an impact, successfully serving our intention of creating awareness about Dakhni. By extension, we also attempt to break stereotypes about the community and paint a human picture of South Indian life, because by highlighting both joys and sorrows, the stories become universal. We hope that the shared humanity that transcends linguistic and national barriers reaches a wider audience, including the global English-speaking community.

You're offering the parts of the series for free online as opposed to the traditional publishing route, where most of your work has seen the light of day. What prompted this approach?

With Hallubol, we wanted to reach a wider audience beyond just Dakhni readers. To do that, we created short motion comics that capture the atmosphere of the Dakhni setting and shared them as reels on social media. These weren’t the full stories, but glimpses—small, standalone anecdotes that explore character relationships. The complete series itself isn’t available online; it’s being traditionally published and distributed at conventions like Comic Con India and Indie Comix Fest, and remains exclusively in print.

Biryani Khaane Jayinge - Quest for Biryani (A Hallubol sidequest) published in Comixense Magazine. Story and art by Rahil Mohsin and Alankrita Amaya.

Biryani Khaane Jayinge - Quest for Biryani (A Hallubol sidequest) published in Comixense Magazine. Story and art by Rahil Mohsin and Alankrita Amaya.How has it been received by local readers?

We’ve had a warm reception. Our quest to create awareness about Dakhni resonated with many, and thanks to the platform provided by events like Comic Con, Hallubol has become a fairly familiar name in the Indian comic market. In recent years, there has been a steady rise in Dakhni representation in Indian media, and Hallubol, being a bilingual comic with real-time translations of Dakhni dialogues, helps non-Dakhni readers connect with the language. We’ve even had instances at events where readers bought our merchandise and comics for their Dakhni friends — a heartwarming gesture of reconnection. Such wholesome experiences over the years have helped keep us going.

You've been working on this series for years. What are your plans for it moving forward?

Our plan is to create a limited series of five issues following an interconnected plot lived through the eyes of an ensemble cast of colorful Dakhni characters as they face everyday challenges, with a sprinkle of dark fantasy elements. So far, we’ve published two issues and are working on the third. We hope to conclude the series arc with issue five and eventually create a compilation issue with behind-the-scenes material to connect with readers beyond the main storyline.

Do you have any other exciting projects that you're working on at the moment that you can discuss, and if so, when can readers expect to see them released?

Apart from Hallubol, I’m working on a short picture book/comic hybrid. I’ve also illustrated two children’s books as part of Room to Read India’s literacy program and am currently working on some children’s book commissions. When I get some time off, I’d like to experiment with a Dakhni–English children’s book to further my aims of preserving our language and presenting our community authentically.

![Ghost of Yōtei First Impressions [Spoiler Free]](https://attackongeek.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Ghost-of-Yotei.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·