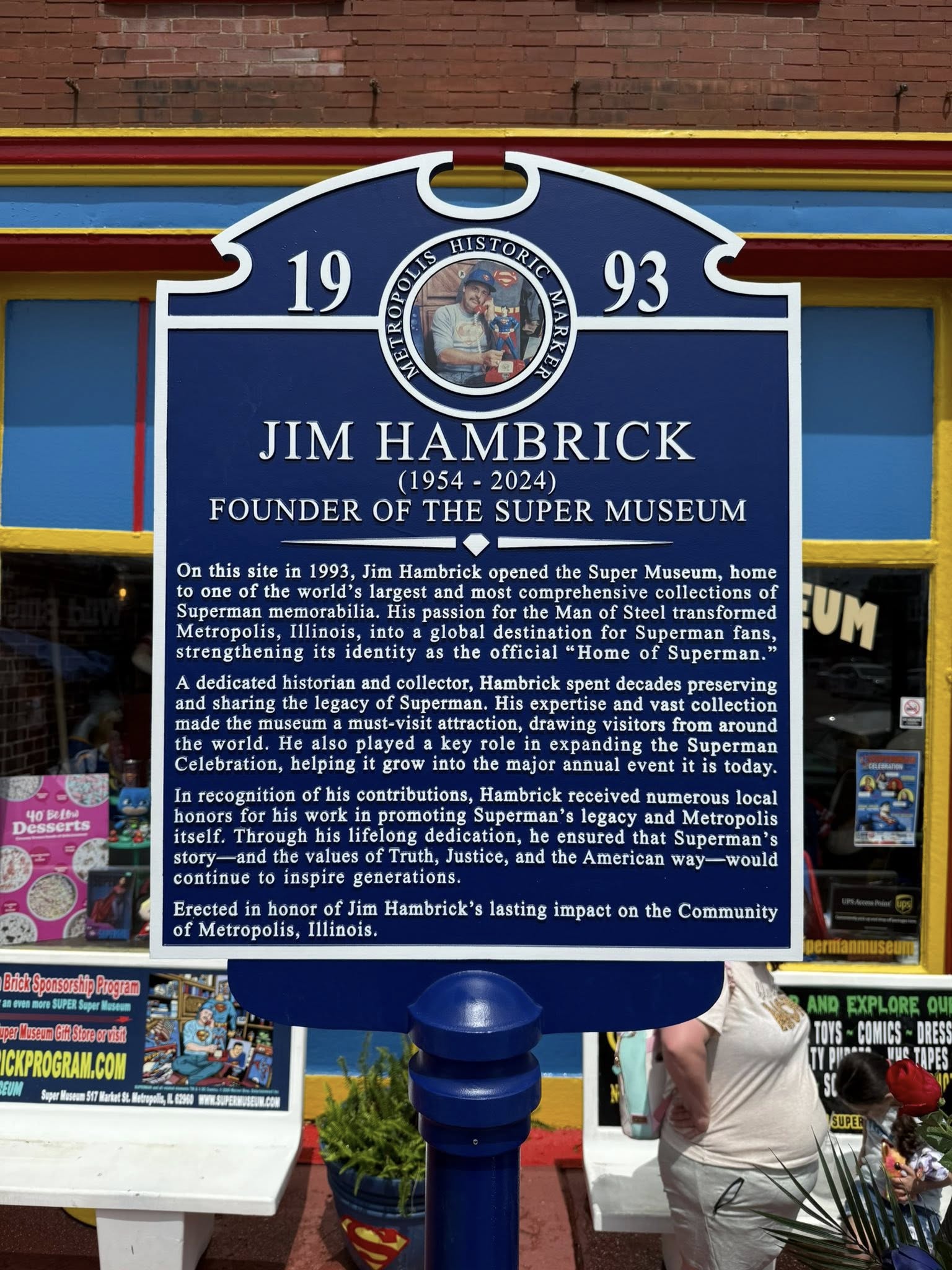

Tom Shapira | June 12, 2025

In ye olden times, on a social media platform that now only exists as a maggot-infested zombie, I asked my fellows: “Who was the best artist on popular British fantasy strip Sláine?” The answers divided the audience into two groups. The first, comprised of longtime fans of the veteran anthology 2000 AD, gave a myriad number of responses from the black and white period: Massimo Belardinelli, Glenn Fabry, Mick McMahon. The second group, those who were not “Squaxx dek Thargo” chose Simon Bisley. Someone, an artist himself, went further and claimed that Bisley was the only artist worthy of even being considered.

Slaine: The Definitive Edition. Art by Mick McMahon.

Slaine: The Definitive Edition. Art by Mick McMahon.This, like choosing Citizen Kane as your favorite film or The Beatles as your favorite rock band, is not so much a "wrong answer" as a "too obvious answer." Yet it speaks plainly to the outsized influence Bisley’s run (collected many times over as Sláine: The Horned God) had not just on the strip but on the face of mainstream British comics. Open a 2000 AD issue in the 1990s and you would usually find someone trying their hand (and brush) at imitating Bisley painted style. Often failing miserably. Like Jim Lee across the pond, an artist of considerable chops with populist appeal who spread his style like a contagion. The Horned God outsold any other Sláine collection many times over (it was the first printed in Hachette’s massive reprint program, 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection), and overwhelmed much that came before and after. So, to most, you said “Sláine,” you also said “Bisley.”

A darn shame, if you ask me. A shame that can now be corrected thanks to the first volume in Rebellion’s The Definitive Sláine, a new series of collections reprinting the series in chronological order (following The Definitive Nemesis the Warlock, and hopefully leading to a definitive The Balls Brothers one day). The first of these collections contains material originally published in the early 1980s and you can certainly see that decade’s notion of fantasy, both good and bad, flashed all over the page. It’s a wild adventure story, not refined or crafted, and all the better for it. Like its hero, it is a story that forever looks for itself, and finds something new.

Slaine: The Definitive Edition. Art by Massimo Belardinelli

Slaine: The Definitive Edition. Art by Massimo BelardinelliBut what is Sláine? Who is Sláine? It's a rarity, a pure fantasy strip in the days when 2000 AD was still adhering to the notion of being a "pure" science fiction magazine. The series focuses on the adventure of the titular barbarian warrior, usually accompanied by his dwarf friend/hustler/chronicler Ukko, as they travel around The Land of the Young, a sort of proto-mythical land of the Celtics, fighting all sorts of monsters and mad magicians. Sláine’s gimmick is the warp-spasm, a rare ability possessed by a select few warriors of his tribe, which allows him to temporarily gain monstrous appearance and even more monstrous strength; and also allows any artist who draws him to go all-out with the weirdness.

Slaine: The Definitive Edition. Art by Angie Kinkaid

Slaine: The Definitive Edition. Art by Angie KinkaidAnother rarity, Sláine is the first strip in 2000 AD to be co-created by a woman. Artist Angela Kincaid drew the first strip, and only the first strip, which was written by her then-husband Pat Mills (Mills remained on the strip and has been the sole author to this day). Mills had a history in Girl Comics, the type of British magazine aimed at a young female crowed, and while Sláine is a certainly strip involving macho action there is something in Kincaid’s more gentle drawing ethos and Mills’ desire to appeal to girls that remained attached to the series as male artists supplemented the first co-creator. Sláine is something of a pretty-boy figure when he first appears, creating a stronger contrast with his warp-spasm transformation, and stands out amongst the gruff and scruffy protagonists of strips like Judge Dredd, Rogue Trooper or Strontium Dog. In future stories Mills would develop the idea of Sláine’s society as a matriarchy, with evil male priests usurping the power of a rightful female goddess.

That is pure Mills, an author forever in tension between well-honed commercial interests, forever pushing for a toy or a movie deal, but also a political firebrand shouting to bring down the man. Even in these stories, more fantastic than the work he was doing in Invasion or Ro-Busters, the writer finds time to stick it to religion, or organized religion at least. The main threat in these stories is Lord Weird Slough Feg, leader of the wicked Drunes who oppress the population. It's a population that usually accepts its lot, because they have been brought up to respect religious authority. Even when writing high-adventure, Mills’ personal politics were front and center; likewise the romanticism towards the ancient Celts as a noble savage type (though with more of the "savage" aspect than usual), compared to the morally-compromised civilized societies of later eras.

Kincaid, alas, survived only one story. By all accounts it was difficult enough to get that chapter published. She was more used to illustrated books and her drawings are somewhat stilted; She draws a good Sláine, a handsome Sláine, and a mediocre everything else. In that she is contrasted with the artist to follow — Massimo Belardinelli. An old-hand for the magazine, the Italian artist drew the revival of Dan Dare that was on the cover of the first issue of 2000 AD. Belardinelli excelled in monsters and gory details. When asked to depict something horrible, a man being consumed by spiders from the inside, a woman turning into a serpent, a trip to the underworld, he never falters. His depiction of Sláine under warp-spasm, is like something Richard Corben would draw — the muscles impossibly huge, the body contracted, the figure only barely keeping its humanity. His drawings are visceral and vital, straddling the edge of excitement and grossness.

Slaine: The Definitive Edition. Art by Massimo Belardinelli

Slaine: The Definitive Edition. Art by Massimo BelardinelliAll of which means his drawing of the protagonist at rest, Sláine when his body was not a screaming pile of muscle-meat, felt oddly out of place. It’s as if the protagonist was the part that excited him the least about the story (you can make a similar charge about his Dan Dare). It doesn’t help that the first long-form story, “The Beast in the Broch,” is a rather confused affair that doesn’t really know what to do with its characters: Having established a status quo of a wandering warrior with Kincaid, Mills immediately set out to upend it, allowing Sláine to go back to his tribe (in theory).

Still, whatever problems there are in the script, Mills always seems to be writing by the seat of his pants, with new notions coming in to shape the story halfway through, only to be overcome whenever Belardinelli gets a chance to draw a particularly horrible tablature. By the time Mick McMahon comes in as a second main artist, Mills has more of a handle on what he wants to do with the strip.

Speaking of McMahon ... well, one cannot help but speak of McMahon. Possibly the finest artist (comics or otherwise) that was birthed on British soil. An exaggeration, but not too much of an exaggeration. Starting out as a Carlos Ezquerra clone by editorial mandate, McMahon quickly went to define his own unique style; one that cannot be defined with any words other than "shaggy" — his figures have this strange lumbering quality to them, a presence unlike anything else. He would continue to refine himself throughout the years, reaching a sort of zenith in the mid 1990s that involved stylizing and flattening the figures while keeping a complete three dimensional awareness. But we’re still ahead of the narrative. His work on Sláine, particularly his longest story, “Sky Chariots,” is still recognizable in a classical British illustration style, with attention given to uniform and filling out the scene with extras. Yet at the same time his drawings are unlike anything else. The figures are exaggerated and realistic for their exaggeration at the same time – the limbs are long and constantly moving, the bodies twist and the mouths open wide agape.

Slaine: The Definitive Edition. Art by Mick McMahon.

Slaine: The Definitive Edition. Art by Mick McMahon.Belardinelli needed scenes of the fantastic to arouse his spirit. McMahon could make any scene, something as simple as an establishing shot of a village, fantastic. It is the kind of work that is pure comics-making, you cannot imagine it transferred into any other medium. There is a true timeless sense to it, forty years later the stuff McMahon drew still looks cutting edge, as if not printed on paper so much as carved on iron; it cannot be dented by the passage of time.

“Sky Chariots” has everything a boy could want, certainly enough to make a grown man remember being a boy again. It’s not a long story, less pages than a typical American story arc, but it has the sense of an epic. Mills does his best to cram events into every page and McMahon rises to the challenge to draw them with an outburst of energy (all without losing his vital mood). Even if everything else in The Definitive Edition was a dross, instead of being uneven, the presence of the McMahon-drawn stories would catapult it to the zenith of fantasy comics. It’s the type of work that seems counter-intuitive, the way the line of figures matches the line of the background without ever getting lost in it, that you have to wonder both why did he go through all that hard labor and how did he even manage it?

Slaine: The Definitive Edition. Art by Mick McMahon.

Slaine: The Definitive Edition. Art by Mick McMahon.Which, on what must be my sixth time or so re-reading that particular story, explains why “Sky Chariots” still works: the art evokes the sense of wonder the characters feel because it is, by itself, a wonder. Forty years later, the story still kicks, slaps and brains you with a mighty axe. It is a mess, in many ways, but such a fine mess.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·