Jacob Ahana-Laba | May 15, 2025

In manga, the "tobirae" (or frontispiece) is often a full-page illustration introducing a story — literally, a "door-page." Tobirae hint at what’s to come, a first impression of sorts. So when manga caption the tobirae with a question, it’s usually followed by another inquiry: who’s asking? Unanswered, a tobirae leans into the confusion of character, narrator and reader. In his manga Rapid Commuter Underground, the mangaka Zjirogh embraces that confusion throughout the story: "What do you do," it asks, "While you’re on the subway?"

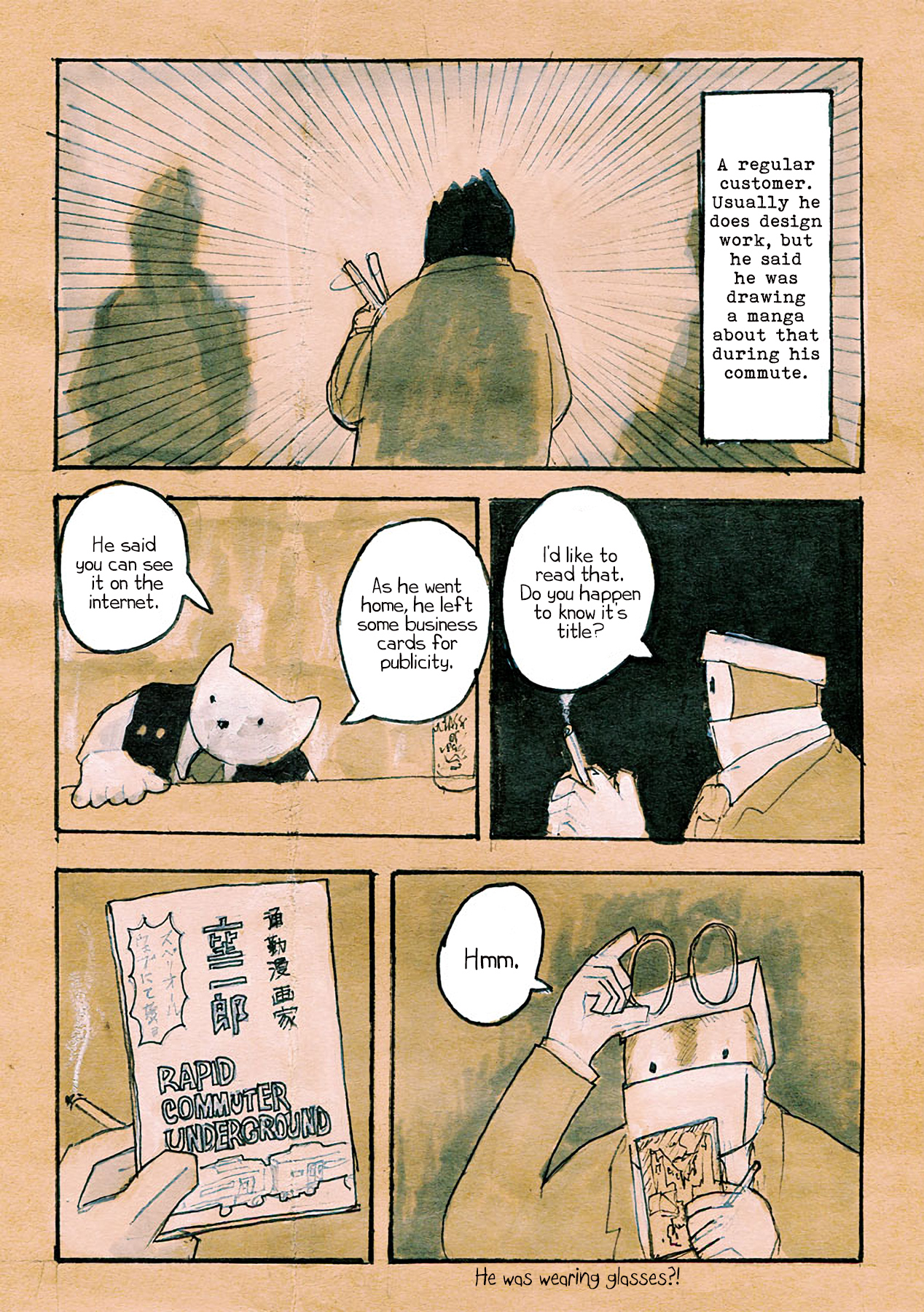

From Rapid Commuter Underground. Note that all English captions have been done by Jacob Ahana-Laba.

From Rapid Commuter Underground. Note that all English captions have been done by Jacob Ahana-Laba.Questions are presumptuous in comics. They’re invitations (if not demands) for reader participation. In the above image, we see the frontispiece with a good deal of people, sitting on a train. They’re distinct, too — one’s exasperated, pinching the bridge of their nose; another sleeps on their guitar’s gig bag, while beside them a woman has an arm-full of shopping bags, maybe held tight to her chest so as not to disturb the man beside her — cross-legged, he reads from a too-big newspaper with slim, slanted glasses. There are nineteen such people (the reader makes twenty). One of them is the main character.

Though they all act, nap, and wear a diverse set of outfits, Zajirogh’s trademark figuration flattens hierarchy. Here, all are stripped of color, indeterminate. All are consumed by the backdrop: watercolor, texture, ink splashing freely. Like clouds in distinct, dynamic shapes, the characters are bent into their aggregate along the paint’s watery skin, as the ecosystem behind — the subway — soaks and dilutes the human form, and makes dominant the collective networks of transportation.

In manga, anime, and Japanese media broadly, trains are a common public space setting. One well-known scene in Miyazaki Hayao’s Spirited Away is the "train scene." Escaping from a bathhouse operable in excesses — overconsumption, commodification of life-forms (even supernatural), working-class deprivation — the train is a place at once beautiful and wholly mundane. In contrast, the novel Night on the Galactic Railroad is an escape into — not from — pure, blissful fantasy, journeying to heavenly hope, celestial excitement. It’s a staple in Japanese literature (even adapted into the manga Galaxy Express 999, itself adapted into numerous animated shows and films).

Really, from the action-packed Demon Slayer: Mugen Train and the hype mystique of Baccano!, to romance-dramas like 5 Centimeters Per Second, the train is dematerialized. Its inner-world is cut to constant, unrelenting motion. Trains exist to drive "off-track," for delays and waiting. Loss of control as a narrative turn, or control as contrast. However, in Rapid Commuter Underground, the story doesn’t merely take place in trains — it is the train.

***

Zajirogh, known in Japan as the "commuter mangaka," studied architecture at Waseda University and worked in design. His corpus’ themes of student- and work-life admit it was anything but strenuous, and his manga (especially the early works) are often adjacent to his weird and weirdly normal life. (“Zajirogh-san’s great at talking about himself,” Taniguchi Natsuko, a mangaka-friend, said jokingly.) Drudgery crops up in his sporadic, largely discontinued work, like the short story Resignation Letter (taishokutodoke), or in longer serializations, like Quit★Salaryman ! Girigiri-kun or Struggling Days: Becoming. In them, he details his dislike of Japanese workplace culture or insecurity in academia, often odds with his character — a lost student without aspirations who constantly retreats to his headspace.

He needed to teach himself to escape. When the inner world collides with the outer world, it manifests as drawing — and soon, his weird, scattered associations make material the true him, in art. For example, in the frankly titled Struggling Days, an earlier work on student life, he’s assigned to read the poem "L’Azur" by Stéphane Mallarmé and express the sky with a model and artwork. He has no clue what to do. But for some reason, he suddenly sees a Lego figure, who declares: "There’s nothing wrong with not knowing." "Eh, who’s that?" wonders the weirded-out student.

"Me?" asks the Lego-person, smile wide, "I’m Mallarmé, of course." And Lego Mallarmé guides our student through his Lego garden, piece-by-piece. Like a mentor, Lego Mallarmé suggests that withholding associations — however weird or disruptive — defeats authenticity.

It all works out: he gives a stand-out performance, scores high. But most importantly, he accepts neurodivergence — and with it, his art. This interplay between experience and physicality redefines his language in architecture. Art, once bland, is now rich and imaginative. He sees worlds anew, and if he sees them, he must draw them.

Zajirogh, Mallarmé’s Skies (mararume no sora) from Struggling Days: Becoming chapter 3, 2021.

Zajirogh, Mallarmé’s Skies (mararume no sora) from Struggling Days: Becoming chapter 3, 2021.Throughout life, being a "salaryman" — a trope of working-class masculinity — weighed on Zajirogh's shoulders. Under the status of an everyday employee, he dreamt of discovering something else, hidden but available. He was educated, knew life in New York briefly as a child and later as an art student. He was eccentric. He had ambitions about art and life.

Eventually, he ended up at a construction company, doing desk work. But between long days and brief rests, he was on the subway, four hours round-trip each day. While on the subway, he dreamt, but not passively. Through his dreams, he created Rapid Commuter Underground. "I continue to draw," he said, "because [if I don’t], I’ll regret the twenty years of life commuting."

Rapid Commuter Underground (or RCU) is surreal. Its exposition has the slow, certain sensibility of autobiography, but always with a vague sense of self-doubt, experienced simultaneously, almost joining the looking-glass of the reader, writer, and characters. Early on, he describes himself as "just an ordinary employee in a company-owned house, doing things like going to Kounan with his family on days off." He introduces us to his process: "Today, there’s a salaryman with an ordinary name drawing manga on the subway somewhere, again." Thoughts exist in captions (not an irregularity in manga). It resembles an I-novel (Shishōsetsu), with the page’s presence allowing a narrational authenticity alongside character-level unreliability. But, as opposed to postmodern play, there isn’t a writer directing us from above. No, Zajirogh is as confused as us. Everyone — narrator, character — is adjacent and equal to the reader. In the same chapter, he introduces his family, his wife. They’re cute. Normal. Then: "Now, I’ve got to get to work again today." And we zoom out, scarcely seeing him in an apartment in chain-link, train-like boxes, resembling a microcosm — and then we leave.

***

RCU takes place in trains, sure, but malleable, metamorphic trains. Trains that, in a split-second, may set walls between passengers, blocking them off from the world, simultaneously creating a collective experience. Trains are sometimes study spaces or apartment blocks. Sometimes long, dazzling train-chains resemble high-rises, or perhaps a bar, a table set.

In each chapter, Zajirogh slips into the subterranean, non-stationary ephemera of what I’d call a transcape. In the liminality of between-worlds, Zajirogh’s transcape marks an interstitial morass breaking through the transit spaces, which are sonically and substantively trance-like. Between the weave of trains, symbols relapse along subtle, self-reflexive recurrences, into a spectrum of seemingly infinite permutations that eventually delineate a narrative.

Without Zajirogh, one might not see the turtle conducting mini-trains as they circle around tracks to deliver sushi to patrons — but in the cracks between subway lines, in the minute-late wait times, anything, it seems, can happen. So let a kappa (a turtle-like river spirit) deliver kappa-maki (cucumber sushi). He sees elephants with ties. He commutes from late-night bars shaped like train cars — lengthy, with thin doors on each end — to the Kasai Rinkai Line, both a train and "an aquarium where you can see fish while riding," shuttling passengers tank to tank. In interwoven vignettes, the repressed imagery of the salaryman projects trains across landscapes. After all, the train — perhaps more than any other public space — is where the daydream crops up. The working-class salaryman is often seen resting on late trains, or fighting to stay upright after drinks with his boss. And Zajirogh notes the worker in all his forms.

What distinguishes RCU from other manga, and Zajirogh from other passengers, is attention. As an artist and aspiring mangaka, he doesn’t let dreams pass, but actively engages with them. Moreover, as a studious observer of city planning and architecture, his associative, collage-like art suggests the eye of an architect in its deeply detailed, interconnected systems of spatial and temporal experience, illustrating planes of macro- and micro-cosmic interaction. Recently, in his series The Superflous City with WIRED.jp, he describes places as breathing human activity. As in RCU, scale is in flux as he studies malls, shrines, mega stadiums and parks. Accompanying art of the Tsukuji Outer Market, he writes, "[Here] lots of people, goods, and wealth come and go. It’s not a building, but a huge 'living thing'." He also writes a great deal about the "Ninth City" — Tokyo — and transportation as an "indicator of time."

Zajirogh, from Moving Through The Times of Tokyo, Life in the Ninth City, 2019.

Zajirogh, from Moving Through The Times of Tokyo, Life in the Ninth City, 2019."I can’t believe I drew nine chapters of whatever came to mind," he admits in RCU. The automatism of RCU often feels like a train ride. Pausing at junctions, sure, but the moment the reader’s in another chapter, it’s as if they’ve never left. Chapters continue into each other, despite RCU’s episodic nature.

The sense of both going and being (as opposed to waiting) lap at each other. "Today I’ll draw the 10th," he writes in the ninth chapter — and it feels as though we’ve already arrived. Time eats itself in these comics, it's never a steady, continuous form. Perception isn’t either. We’ve seen sleeping, probably dreaming salarymen. We’ve seen children peeking out of windows, seeing superheroes on rooftops. When he becomes aware of his daydreams, the manga itself seems shocked, as if waking from a deep slumber. He loops us into the process of creation — RCU was born on his train rides, after all — and so this fourth wall collapse is gentle and expected. Block-like color and collage encroach on a semblance of reality or continuity. Throughout the manga he talks to himself, and he makes clear his perspective, both as a mangaka and as a character. The dream-world falls apart; he’s ashamed of daydreaming. It is then that he begins to lose confidence — and without confidence, he loses his sense of art. Soon, he departs.

From Zajirogh's Rapid Commuter Underground, chapters 10 (pages 3-4) and 11 (pages 1-2).

From Zajirogh's Rapid Commuter Underground, chapters 10 (pages 3-4) and 11 (pages 1-2).While the mangaka is eclipsed by the salaryman’s daily life, other personas — of himself, of us, collectively — take precedence. Because he draws RCU on trains, he’s riding working-class life with us, experiencing both the creation and expectation of art seen. The subway becomes a home he brands "the last sanctuary of the salaryman." And we experience the suddenness of self-reference together, assuming personality as an onlooker, but an onlooker of onlookers, a narrative ouroboros (perhaps a hyper-loop) recurring in the pluralities of temporal instance, retrospects and present times.

From Zajirogh's Rapid Commuter Underground, chapter 11 (pages 4-6).

From Zajirogh's Rapid Commuter Underground, chapter 11 (pages 4-6).A quiet, anti-capitalist criticism of the "salaryman" — and the institutions ensuring the image of hard work as personhood — emerges between the tight joints of working-class realism. RCU grows into a narrative centered around hidden dream-worlds. We see a fan, in love with his work; Zajirogh working, losing touch with himself; and above all, bourgeois dream-creatures hiding the worlds of "more" from the worker. When we lose Zajirogh, a monkey-man appears in his place. The monkey-man has an exaggerated, bourgeois nonchalance: hands in his pockets, hat tipped a touch. We see the monkey-man lead himself down ornate but lifeless hallways. He meets a shrouded, dark figure, like a boss or executive never seen, never known as human. They say: "So that mangaka —" before the monkey-man interrupts, saying, "No, just a salaryman." One can’t be both. Creatives and salarymen are contradictions. He describes the issue: "It seems like he’s drawing a manga about 'it' on his way to work." (There’s humor here: those "in charge" notice how much of an issue the "commuter mangaka" is because "he updates his twitter about it.") By living in art and dreams, this weird, anxious salaryman/mangaka thus becomes a creature of resistance.

This narrative turn is a silly, but deeply affecting satire: a sole fan searches for RCU’s mangaka. ("Awaken, Zajirogh! Rediscover your manga, your world!" we cheer from the sidelines.) She discovers a slouched salaryman on a train , dead to the world. It is, indeed, Zajirogh but he’s nearly forgotten he ever drew manga.

On a mission, she slips into the transcape. Throughout her adventure, symbols recur: a sparrow, an art store. She meets Zajirogh’s friends, crocodile and rabbit, and is shown the world’s labyrinthian map. But she never crosses paths with him. Instead, he’s at work, distressed and hyperventilating — he has a report due. To treat his anxiety, he talks to a doctor and is prescribed JZOLOFT. This is all, it seems, puppet-mastered by a low-profile but always-dominant bourgeoise. Though various dream-symbols appear, they don’t register with our hero. He’s lost: "Somehow I feel like I’ve been riding [the train] for some time," he says. "For days, no, maybe years…" When he returns to his messy, isolated home — no family, no children — the dark, somber panels feel suffocating.

From Zajirogh's Rapid Commuter Underground, chapter 21 (page 6-8).

From Zajirogh's Rapid Commuter Underground, chapter 21 (page 6-8).He soon encounters the girl again. They talk. She, about her search. It rings a bell, he thinks. There’s something, but it’s elusive. Then suddenly, he remembers. While he scrambles for his bag, immediately a voice of authority sounds from an overhead speaker to "Stop drawing things on the train!" He wakens and takes out his manga. The train makes an "emergency stop," but too late; he has rediscovered a life beyond work ("I actually do have a wife and kids!" he exclaims). Bright-colored panels return full-force, living not below, or adjacent, but within reality. He’s found himself. A hero of the ordinary, defeating an elite’s constraints, encroaching permanently on their thresholds, redrawing their boundaries. He’s revisited the world of dreams and realized it in his art.

As the manga winds-down, he’s discussing with his editor this manga — he’s actualized life lived as a passionate, real-life mangaka; sometimes disappointing, always fruitful. And while going about his colorful life, some bright-yellow elephants walk beside him. They shop, stroll and go about an everyday life, breathing the art of the world together.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·