Kristian Williams | June 4, 2025

Sue Coe — political cartoonist, visual essayist, and long-time contributor to World War 3 Illustrated — naturally has a lot to say about the state of Trumpian America. The Young Person's Illustrated Guide to American Fascism features well over a hundred of Coe's illustrations, depicting aspects of our once-creeping, now-racing authoritarianism — propaganda, poverty, war, police brutality, medical neglect, environmental destruction, animal cruelty.

Animals, in fact, occupy a central place in Coe's iconography. Idealized and innocent, they sometimes stand in for all victims of pointless abuse; they incarnate (one is tempted to say "personify") the natural environment; and in at least one instance, they serve as a symbol of hope. That image shows a multiracial circle of children, sun rising behind them, as they release a bird and it takes flight. Another child, hair in pigtails and shovel in hand, stands over a fresh grave marked:

RIP

HATE

FASCISM

WAR

Some of Coe's images stand out with the simplicity of a classic newspaper cartoon; others, like "Triumph of Death Cult" are complex grotesqueries, somehow simultaneously surreal and medieval in appearance, like a twenty-first century Hieronymus Bosch. In her depiction of the January 6 revolt, however, surrealism converges with realism. They can no longer be distinguished, so delirious has our reality become. It is a paradox of our time that Trump's inherent intemperance and native absurdity frustrate all attempts at satire while lending themselves so well to caricature.

Coe's work makes the most of this contradiction, exaggerating the president's physical features to depict the inanity, insanity, and ugliness of his policies. Whatever the approach and tone of a particular piece, Coe's work always displays a nightmare clarity. It is only unfortunate that in this collection the small size of the pages makes it difficult to appreciate the grueling detail of the more intricate images.

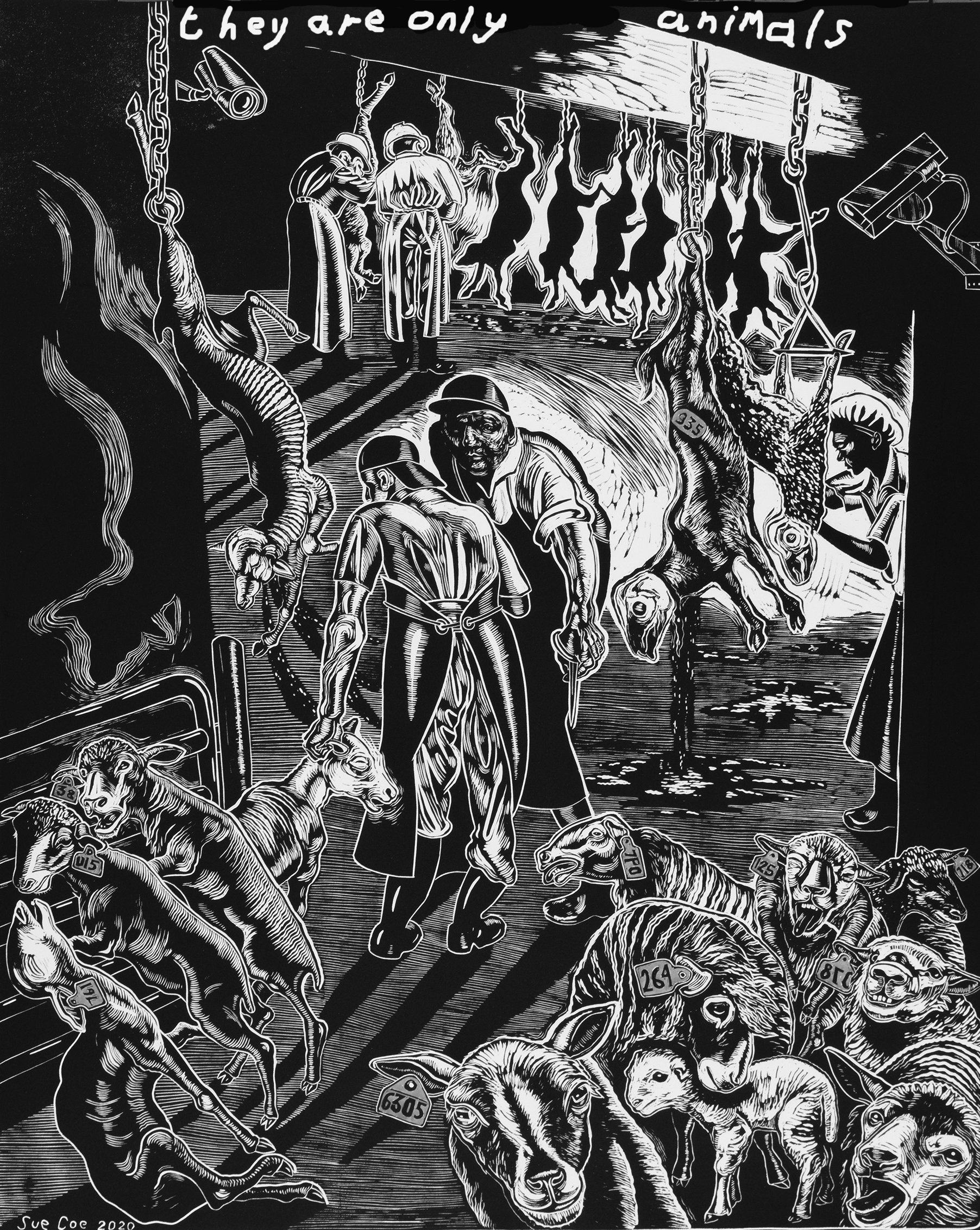

An essay by art historian Stephen F. Eisenman introduces the volume — and comprises a fifth of its total page count. Eisenman attempts to supply the context for Coe's work by relating it both to the history of fascism and to the present state of the country. It is a lot to take in, and largely unnecessary. Though Coe's images are dense and could no doubt be profitably analyzed at some length, their impact is visceral and does not really require explication. The images of children in handcuffs, of animals being slaughtered, of Trump molesting the Statue of Liberty — these all speak for themselves. Moreover, Coe's expresses her intuitive moral grasp that all injustice is connected quite powerfully in visual terms without any need for theorizing in prose. Viewing the slaughterhouse scene in "They are only animals," one either relates the suffering of the terrified and dying sheep to that of the two workers standing in the center of the frame, monitored from all sides by surveillance cameras — or one fails to. A ten-part definition of fascism is unlikely to help.

There is a great deal of interesting historical detail in Eisenman's essay (who know that Fred Trump was once arrested at a Klan rally?), but its political analysis is unfortunately muddy. Eisenman tries to argue both that fascism is imperiling American democracy and that the United States has always been fascist. There is a lot to be said for either proposition, but together each would seem to undercut the other. To reconcile the two, Eisenman proposes a perspectival understanding of fascism, by which slavery, segregation, and lynch-law were fascist from the point of view of African-Americans, just as colonization and genocide were fascist from the point of view of the indigenous population. It is a powerful rhetorical move, if an over-familiar one, but it also seems to rob fascism of any distinctive character, rendering it merely a synonym for oppression.

Of course, oppression is bad enough, and perhaps it is worse if the oppression is also fascist. But I suspect that the need to bend all injustice so that it points back to a purported fascist center, or else to expand the definition of fascism so that it covers every conceivable cruelty, evinces a certain poverty of our political or moral imagination. We have accepted a single absolute evil, and so it becomes the standard by which all else is judged. Of course, there is still a very good case to be made that Trump, or at least his regime, is fascist. But Eisenman doesn't make it, and Sue Coe doesn't need it.

![How To Read The Animorphs Graphic Novels [Guide + Reading Order]](https://www.howtolovecomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/animorphs-guide-feature.webp)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·