John Kelly | May 5, 2025

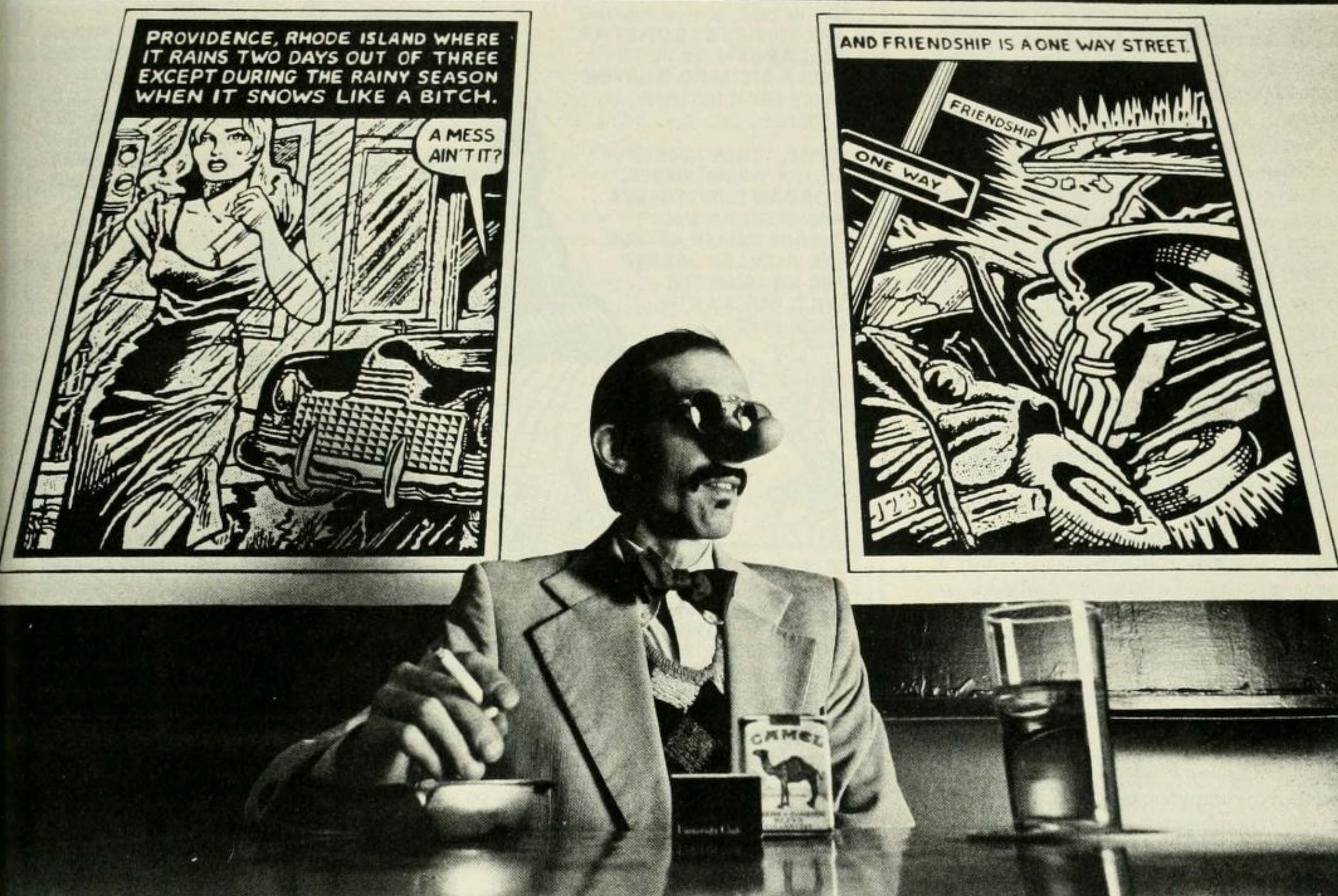

The Mad Peck, with his customary pack of unfiltered Camel cigarettes, ca. 1980. Image courtesy Brown University.

The Mad Peck, with his customary pack of unfiltered Camel cigarettes, ca. 1980. Image courtesy Brown University."The entire history of underground comix has two stories: One revolves around a handful of able, slightly ajar minds; the other is part of an ongoing American tradition–anti-bullshit and pro-fun." — John Peck, from a history of underground comics in Fusion #36, 1970.

In his long and very diverse career, the Mad Peck straddled both camps.

John Peck, the underground cartoonist, music and comics historian, disc jockey, pack rat, and many other things, better known as the Mad Peck, and sometimes known as Dr. Oldie, died on March 15 in Providence, Rhode Island. He was 82. The New York Times reported the cause of death to be a ruptured aneurysm in his aorta.

A representative example of Peck's comics that ran in national publications in the 1970s and '80s. This one featured his Masked Marvel and I.C. Lotz characters, along with a host of guest stars lifted from the funny pages and elsewhere.

A representative example of Peck's comics that ran in national publications in the 1970s and '80s. This one featured his Masked Marvel and I.C. Lotz characters, along with a host of guest stars lifted from the funny pages and elsewhere.A mysterious figure on the fringe of the underground scene, Peck was the designer and a writer for his friend Les Daniels' groundbreaking book on comics history, Comix: A History of Comic Books in America (Bonanza Books/Crown, 1971), one of the very first books to seriously explore the comics medium. He also published several small booklets and novelty catalogs featuring his work through his Mad Peck Studios during that era and his strips appeared in important counterculture publications like the East Village Other and the Chicago Seed. As a music critic, he concocted a style of reviewing albums in comic strip form; several versions of this series ran in many alternative and music publications, including The Village Voice, Rolling Stone, Creem, Fusion and, briefly, SPIN. Peck later revamped the strip as "This Week in TV History," which focused on television programs. Another incarnation, "Flash Burn Funnies," included Peck's suggestions for making the best mixed tapes.

An ad for Peck's first financial success, a T-shirt for the J Geils Band.

An ad for Peck's first financial success, a T-shirt for the J Geils Band.Peck's reviews/comics strips were acted out by a rotating cast of static cartoon characters Peck had devised and at times his work employed the skills of other artists and writers–thus the Mad Peck Studio title. He said he chose to employ the voices of other collaborators to bring differing viewpoints to the piece of pop culture being examined.

"By employing more than one character in a review, that gives you many voices," he told NPR's Terry Gross in a 1987 interview. "I would not necessarily be speaking to you, but perhaps the people who appear in another panel of the cartoons would be [speaking to your interest.]"

And he also did many, many other things. He produced numerous ads for local Providence businesses, created popular post cards, concert posters, flyers and T-shirts for rock bands, including one for the J. Geils Band which was his first financial success. As a student at Brown University, he developed a computer analytic system for predicting the the outcomes for the Monopoly board game. He had a "T-shirt of the Month" scheme. For a time, he owned a thrift shop called Airline Salvage. He even worked as a male model for a clothing store. And he collected things. More things than you could imagine.

Peck's 1968 poster for the band Cream's final U.S. concert. Courtesy Dummy Archives.

Peck's 1968 poster for the band Cream's final U.S. concert. Courtesy Dummy Archives."He had his fingers in a lot of pies," said Robert Yeremian, owner of the Providence comic shop The Time Capsule and longtime friend of Peck's. "He was consulting with Time Life when they were putting out all those CD collections you'd see advertised on TV in the early '90s ... there's so much ... every night I find something new about him or something I forgot about."

Despite having very limited drawing skills himself, Peck had a great eye for the work of other artists and blatantly sampled and remixed existing artwork for his own purposes. His artistic style was a combination of swipes, collage, clip art, tracing and vintage advertising image détournement. But whenever a Peck image appeared in a publication, it was immediately recognizable as his, because, like everything else about him, it was ... odd. An intensely private person, Peck told me in a 2022 interview that he had not been photographed without wearing a mask or disguise in more than 50 years. He told many others the same thing.

"He wanted to be able to go to the grocery store without being recognized," said Darren Hill, owner of POP, a popular culture emporium and entertainment venue in Providence, where Peck was a regular visitor. "He was very quiet, but if you showed some interest, the information would flow out of him and he was just so knowledgeable about everything, from rock and roll to comics to art in general and even things like engineering. He was just a wealth of information."

"I think he'd wanna be remembered through his work," said Ben Berke, who profiled Peck for the Providence Journal in 2018. "He was never really that hungry to be written about. He refused to be photographed ever, so he definitely wouldn't wanna be remembered by a photograph. His work was brilliant and I think, like so many artists, that was the most comfortable way he knew how to interface with the world. He left a lot of good work behind so I'd say he'd want you to go find his stuff and read it."

***

Peck as a fashion model for a clothing company advertisement, ca. late 1960s/early 1970s. Note the unfiltered Camel cigarette. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.

Peck as a fashion model for a clothing company advertisement, ca. late 1960s/early 1970s. Note the unfiltered Camel cigarette. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.John Frederick Peck was born on Nov. 16, 1942 in Brooklyn, NY. He grew up in Fairfield, Connecticut, listening to New York City radio programs, including an influential one hosted by DJ Alan Freed on WINS-AM. A gifted high school student (he had considered attending the Massachusetts Institute of Technology), he graduated from Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, in the mid-1960s, majoring in engineering. Peck hated engineering and it took him seven years to graduate from Brown; he also briefly studied at the Rhode Island School of Design and New York University. After Brown, he settled in Providence, where he established himself as a local entrepreneur and colorful character, creating, among a host of other things, a popular poster about the city that celebrated it in a loving and acerbic fashion.

"It's hard to describe how he fit in so well in Providence's weird scene, from always present at area flea markets scrounging through boxes for artifacts, comics and otherwise, to local comics get-togethers, where he would pull out his checklists, all written in microscopic yet legible handwriting, as he rummages through coverless comics in search for a Matt Baker-drawn treasure," said comics historian and Rhode Island resident Jon B. Cooke.

Peck collected records, a great many of them, and other items of popular culture, including comic books. He is said to have had a record collection of more than 15,000 LPs and 30,000 45s. During much of the 1970s, and up until 1983, he hosted the "Dr. Oldie's University of Musical Perversity" radio program on Brown University's radio station WBRU-FM. On the show, he played a wide variety of obscure music from his massive collection, which he called his "Giant Jukebox."

Peck's Dr. Oldie persona.

Peck's Dr. Oldie persona."When I was a kid, I thought I'd like to have a radio format where people could call up and ask to hear any record and that's essentially what the 'Giant Jukebox' is," Peck told the Brown University alumni magazine in 1980.

While the "private citizen" Peck regularly frequented comic conventions, swap meets and flea markets, he slipped through the crowds anonymously and without fanfare, often dressed in a trench coat and hat. But in his Dr. Oldie persona, Peck would appear in public adorned in a lab coat, gloves, stethoscope and head mirror. By comparison, his "Mad Peck" costume was simpler; a large rubber nose and dark glasses. In the Providence community, for many, he was far better known as Dr. Oldie than he was the Mad Peck. Some never made the connection that they were he same person.

Peck's Dr. Oldie (left) and Mad Peck (right) disguise kits. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.

Peck's Dr. Oldie (left) and Mad Peck (right) disguise kits. Courtesy Robert Yeremian."Dr. Oldie was his bread and butter at that time," said Yeremian. "Him being Dr. Oldie was probably more prominent for a long time, when he was doing the shows on FM radio, and he was doing local DJ nights."

Some boxes of Peck's Dr. Oldie programming logs. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.

Some boxes of Peck's Dr. Oldie programming logs. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.Peck was a regular at POP, an enormous space that serves as a gathering place for the local arts scene, and for the past decade he could often be found sitting in the same chair near the cash resister where a sampling of his work was on display.

"I had known about him, you know, the myth and the legend, ever since I moved to Providence in 1989," said Hill, a former musician (Red Rockers) who also manages bands and acts. "But I didn't actually meet him — I didn't know he was still alive — until he came wobbling into POP one day and introduced himself to me. It was our grand opening ... and ever since then he would come into POP every Saturday or Sunday, consistently, until the week before he died. Sometimes customers would recognize him, but mostly they had no idea they were in the presence of greatness."

Yeremian was a teenager when he first met Peck at a comic convention and had no idea who he was at the time. A few months after their first meeting, Yeremian bought some comic books off Peck at another convention; Peck then invited him to come over to his house.

"And when I went over the house, that's when I realized he was the Mad Peck," he said, adding that the sheer amount of collectible material he saw was overwhelming. "When I walked into his kitchen for the first time I knew this guy was a hardcore collector. There was just boxes and piles of comics and magazines everywhere. I put two and two together and our friendship just grew from there."

Over the past several decades, their relationship had several different incarnations.

"He was family to me," Yeremian told me in a Zoom interview. "He wasn't my blood relative, but … he was my family. He started off as a friend and then he sort of became a father figure and then sort of morphed into more like an uncle and then a brother and, you know, by the end, he was like my kid ... I was taking care of him."

Up until a few years ago, when he moved into a smaller location in nearby Pawtucket, Peck lived a large brick home, constructed in the 1800s, in the Providence's Federal Hill district.

"It was the oldest home in the area," said Yeremian. "It should have been on the historical register. It was built when that was still all farmlands. So it was a three-family house and he occupied the second and third floors, and there was a tenant on the first floor. By the time when I first met him, it was already kind of run down."

Peck owned a lot of stuff and the house was filled with it, to the extent that the piles and boxes of magazines, records, comics and other ephemera collected over the course of six decades of scavenger hunting made it difficult for visitors to navigate.

"Over the years, the house just got a little bit more run down, and more run down, and got more full and...I'm a big guy and toward the end, it was tough to maneuver because [Peck] was so super thin...his pathways were for somebody his size, not for somebody my size," Yeremian said.

A sampling of Peck's archives. The sheer amount of material, all meticulously cataloged but under piles of debris, was head spinning. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.

A sampling of Peck's archives. The sheer amount of material, all meticulously cataloged but under piles of debris, was head spinning. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.Hill said that despite receiving several invitations, he never visited Peck's house.

"He invited me a couple of times, but I was a little apprehensive about that. I had heard stories," Hill said. "The ceiling was literally collapsing above him and I heard stories that you could barely walk between the stacks of stuff. It was all, I think, nicely organized but just massive amounts of it."

So, was Peck a hoarder, or just someone who had a lot of things? Yeremian: "He was 20 percent hoarder, and 80 percent collector. If anybody else had gone over to that house, or his current house that he was living in, they would look at him and be like, this guy is a hoarder. Because the top layer of everything was disorganized and just sort of piled on top of each other. But that's because he just wasn't feeling well for the last few years and didn't have the energy to really keep up on things. But once you remove that 20 percent of clutter, all of a sudden you're like, whoa, this is a very well organized collection. His 45s are all in alphabetical order by record label and all of his comics are organized by genre or publisher and decade."

Original art by Peck, 1980. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.

Original art by Peck, 1980. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.When asked if there was much of Peck's original art left behind, Yeremian paused for a moment.

"The problem is when we say 'original artwork' and 'Mad Peck' ... those words don't exactly jibe together because everything he did was traced."

***

"Never draw anything you can copy, never copy anything you can trace, never trace anything you can cut out and paste up." — An often repeated quote that is attributed to Wallace Wood. Whether or not Wood ever actually said it, Peck claimed that, in a "chance encounter," Wood once repeated a version of the quote to him as career advice. Whether or not that actually happened, it was an approach Peck enthusiastically employed in his own art.

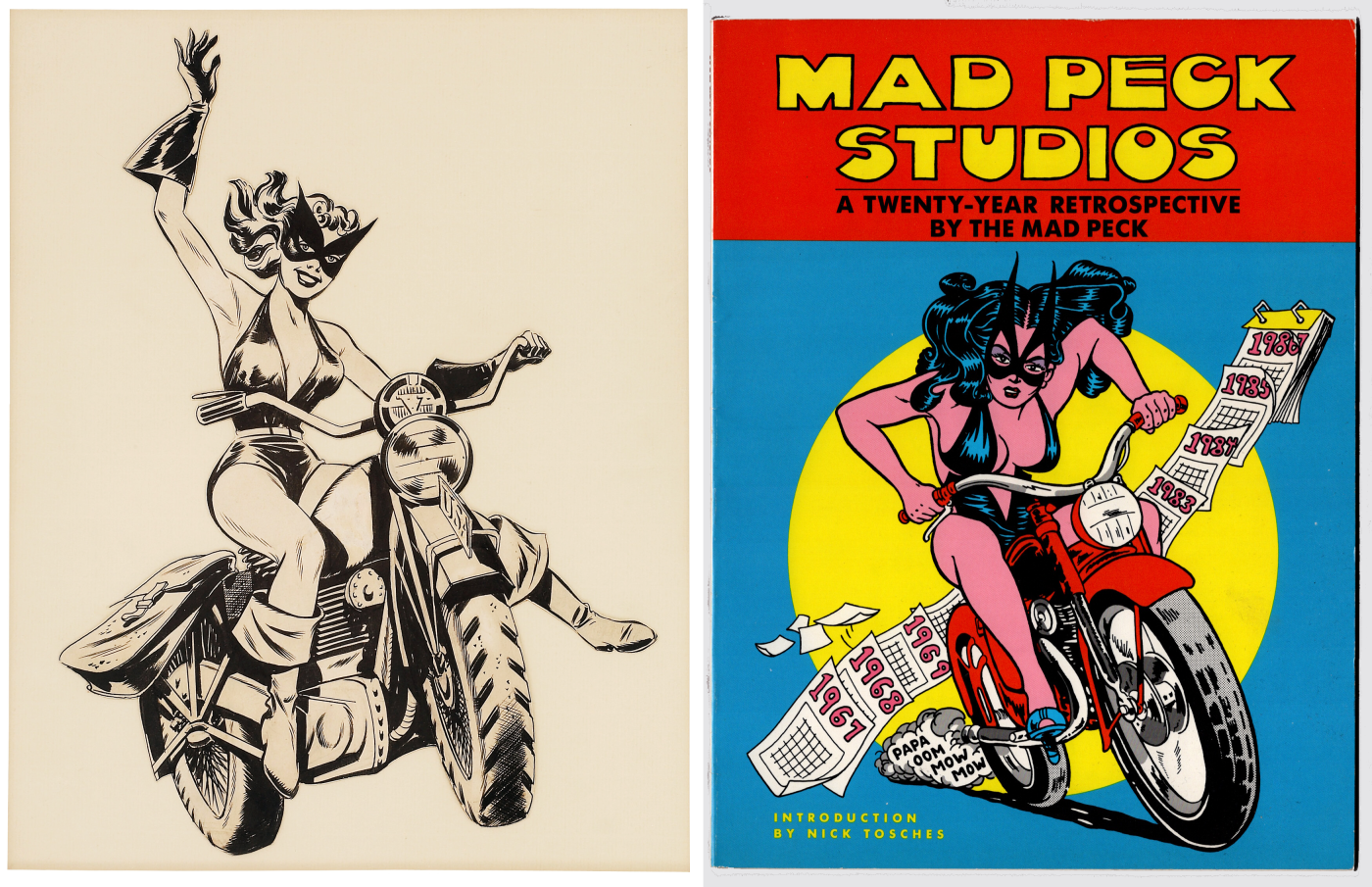

(Left) Lee Elias, original art for the cover of Black Cat Comics #1, 1948. (Right) Peck's art for the cover of Mad Peck Studios: A Twenty Year Retrospective (Dolphin/Doubleday), 1987. Elias art courtesy Heritage Auctions.

(Left) Lee Elias, original art for the cover of Black Cat Comics #1, 1948. (Right) Peck's art for the cover of Mad Peck Studios: A Twenty Year Retrospective (Dolphin/Doubleday), 1987. Elias art courtesy Heritage Auctions.An admittedly limited draftsman ("I can't draw anything myself, except for psychedelic hand lettering," he told me), Peck was a master of the swipe and reuse of pasteups. He used variations of the same images over and over. A number of his stock characters had two basic, often repeated, poses–looking in one direction, or looking in a different direction–sometimes with some limited image manipulation to convey mood. Pittsburgh native Matt Baker is the most often cited source for providing Peck with reference material, but there were countless others. He "borrowed" images from a wide array of anonymous 1940s and '50s advertising artists, animators and fairly obscure Golden Age comic book cartoonists.

A Peck image from Mad Peck Studio: A 20 Year Retrospective (left) and a Matt Baker Flamingo promotional illustration (right) from 1952, Baker image courtesy Heritage Auctions.

A Peck image from Mad Peck Studio: A 20 Year Retrospective (left) and a Matt Baker Flamingo promotional illustration (right) from 1952, Baker image courtesy Heritage Auctions."I became an avid fan of John Peck's strips and faux advertisements when I was a late teen," the graphic design historian Steven Heller wrote in his Daily Heller column after Peck's death. "He was among the first comics artists I saw in the late 1960s who was copping an old-school '50s-era style, not just for nostalgic reasons alone but because he was a conservator of passé pop culture that he interwove as a narrative conceit."

This mishmash of vintage or forgotten influences is found throughout all of Peck's work–a hybrid of comic, film, television music and advertising images.

"All popular culture is connected," Peck told NPR's Terry Gross in 1987. "I mean, when you get down there on the street level or on the consumer level, people don't really make the distinctions between one medium and the other. And in fact, if you watch television, television is actually bringing you every other medium of entertainment and advertising. And when you go out on the street, you're bombarded with TV images to reinforce what they've told you on TV. So it's not a question of being for or against it. It's going with the flow."

A page from Peck's Mad Peck Studio: A 20 Year Retrospective which shows examples of a few of the artists he cribbed from in his work. Examples of work from Jack Cole, Gilbert Shelton, William Glackens, among many others, can be seen here. Image courtesy Patrick Rosenkranz.

A page from Peck's Mad Peck Studio: A 20 Year Retrospective which shows examples of a few of the artists he cribbed from in his work. Examples of work from Jack Cole, Gilbert Shelton, William Glackens, among many others, can be seen here. Image courtesy Patrick Rosenkranz.###

"If someday you should be walking down the street in Rio, Paris or Palm Springs and we should meet by chance, let's just pretend we don't know each other, okay?" — From Peck's Afterword to Mad Peck Studios: A Twenty Year Retrospective

Peck was a very private person and one who seemingly had a phobia to cameras, as very few images of him exist. Several of the images of him shown in this article have never been seen by the public.

"He was the J.D. Salinger of comics," Hill said.

When asked why he was so averse to being photographed, Peck told me, "Since I had the likeness of Dr. Oldie, which I consider much more handsome than myself, I thought, 'why should I let myself be photographed when I had this wickedly handsome cartoon representation to show to the public?'" This posed a challenge to cartoonist Drew Friedman when he chose Peck as a subject for Maverix and Lunatix: Icons of Underground Comix (Fantagraphics, 2022), his book of portraits of members of the underground comics era. Somehow, Friedman was able to uncover an image of Peck for his illustration.

"When I finally found out what he looked like, I realized that he was a John Waters doppelganger," Friedman said.

Peck at the Brown University radio station, WBRU-FM, ca, 1970s. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.

Peck at the Brown University radio station, WBRU-FM, ca, 1970s. Courtesy Robert Yeremian."People tell me I look like John Waters," Peck told me in 2022. "Which is fine with me because people used to say that I looked like Frank Zappa cuz I used to have a mustache and a little bitty goatee ... I'm really grateful that Drew included me [in the book] and as the saying goes, even though I have no real idea what I was doing, I'd say that I did a half-decent job."

Peck in a rare photo, holding a copy of Drew Friedman's Maverix and Lunatix, 2022. Photos courtesy John Peck.

Peck in a rare photo, holding a copy of Drew Friedman's Maverix and Lunatix, 2022. Photos courtesy John Peck.When I spoke with Peck in 2022, he expressed surprise — and gratitude — for his inclusion in Friedman's book of notable underground artists.

"He was always very bitter that the underground comics community hadn't embraced him more," said Yeremian. "He definitely felt like he got snubbed. There definitely were guys in the scene back in the day who didn't like him because he was tracing everything. But then, there were others, like Justin Green. They were very close."

"[Peck was] an underground press pioneer," said cartoonist Bobby London, a contemporary of Peck's. "He was ahead of his time and if I made a list of all the artists swiping his licks today, I'd be in more trouble than I already am."

"Mad Peck was an enigma," said Gary Hallgren, another underground cartoonist. "Never came close to meeting him. He has always been in my library, though."

A note from Robert Crumb to Peck from 1969. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.

A note from Robert Crumb to Peck from 1969. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.Among the thousands of letter of correspondence in Peck's archives is a complimentary handwritten postcard from Robert Crumb. But the alienation from his underground peers existed and it bothered Peck. In a post on his Facebook page at the time of the publication of Friedman's book, Peck wrote: "I wish to thank Drew Friedman for using his artistic vision to suss out my secret physical identity beneath my Dr. Oldie disguise since I haven't allowed myself to be photographed in over fifty years. It was an unexpected honor since I was 'expelled' by the comix establishment in the early 1970s for selling out to the rock press; Creem, Fusion, etc."

When I asked him how it was even possible to be "expelled" from the underground comic establishment, he said: "The nicest way that I can put the situation is that living in Providence and not wanting to leave Providence, I was never able to pal around with the underground comics establishment particularly. I did go into New York a few times. Primarily became friendly with Spain Rodriguez and Kim Deitch, who was editing Gothic Blimp Works (the comix supplement connected to the East Village Other hippie newspaper) at the time. So I contributed some work to some of their later issues. I always felt a kinship to the East Village Other because that's how I got started. There was a little variety store near the Rhode Island School of Design and somebody arranged for them to carry the East Village Other there. And that's where I got the idea of advertising for, like, pipes and papers ... because some friends of mine who were instrument makers, they made banjos and guitars and they cut blocks of hardwood, like rosewood and ebony and so forth, to make extra instruments, and then they made pipes out of the pieces they cut out. And also, I found out where to buy cigarette papers wholesale. So I decided to advertise in the East Village Other, little ads that you see in the beginning of my anthology (Mad Peck Studios), and like everybody else I was influenced by Harvey Kurtzman, who had once done a parody of those little ads that appeared in men's magazines. And that's how the catalog got started. And then people from the Rhode Island School of Design and other local artists and myself started filling out pages of the catalog with cartoons. And that's how I fell into the whole thing."

A spread for The Mad Peck Catalog of Good Stuff, 1969. Courtesy Dummy Archives.

A spread for The Mad Peck Catalog of Good Stuff, 1969. Courtesy Dummy Archives.The "whole thing," or what got his comics career started, came in the form of the often whimsical ads for unlikely products Peck designed and distributed through the Underground Press Syndicate (UPS), which had been providing free content to alternative and counterculture publications since the mid-1960s. Each week, Peck would send a selection of ads for hippie novelty items and some of his early comics strips to UPS and his work would appear in small newspapers around the country. He soon began self publishings tiny catalogs that contained the ads, as well as comic strips for filler. Ads for the catalogs were also distributed via UPS.

A few of the novelty items produced and sold through his ads and catalogs. Courtesy of Robert Yeremian.

A few of the novelty items produced and sold through his ads and catalogs. Courtesy of Robert Yeremian."All it cost was a stamp a week, which was a great scam," he said, "I think most of [my] customers sent away for [the catalog] just to see what the hell they'd get. [I] didn't care. [I] made a nickel for every catalog sold."

Peck's 1969 catalog of hippie novelty items and comics. Courtesy Dummy Archives.

Peck's 1969 catalog of hippie novelty items and comics. Courtesy Dummy Archives.The catalogs offered drug paraphernalia, hippie posters, T-shirts, and a number of items whose function was unclear. They also had Peck's comics. A digest size version of the catalog, complete with a color cover, was produced in 1969. That same year, Peck published Ghost Mother Comics (Pirate Press), featuring his work, as well as art by S. Clay Wilson and some of Justin Green's earliest comics. Green had met Peck in 1967, before he became a cartoonist and while he was studying painting at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence. When I interviewed Peck in 2022, he told me that he and Green bonded over their shared love of music and comics.

Peck's Ghost Mother Comics, 1969. Courtesy Dummy Archives.

Peck's Ghost Mother Comics, 1969. Courtesy Dummy Archives."The Mad Peck...was really a seminal influence," Green told The Comics Journal in 1986. "He encouraged me in my drawing, and he was a very knowledgeable music critic. He did all kinds of little cartoons with the help of assistants, and he published the Providence Extra." In a 1972 letter to the underground comix historian Patrick Rosenkranz, Green wrote: "The Mad Peck started to promote me to the Providence Extra, much to the consternation of the editors there. They didn’t dig my work. A lot of people are really turned off by my drawing style, but that’s another story."

Early Justin Green work from Ghost Mother Comics, 1969. Courtesy Dummy Archives.

Early Justin Green work from Ghost Mother Comics, 1969. Courtesy Dummy Archives.Peck achieved his greatest financial success through an often reprinted poster celebrating the city of Providence that first ran as a page in Loose Art #1, a Providence literary journal in 1978. Developed with frequent collaborator Les Daniels, Peck composed the image as a series of comic strip panels, referencing Providence streets in a humorous manner.

Production art for a postcard version of Peck's Providence poster. Courtesy Dummy Archives.

Production art for a postcard version of Peck's Providence poster. Courtesy Dummy Archives."That's what kept him alive for a lot of years because there's this saying around here that every freshman at Brown University, for 40 years, had that poster hanging in their dorm room," Yeremian said.

Over the years, POP has sold hundreds of copies of the poster, as well as the postcard version. When I spoke with Hill, he said he hoped that the iconic poster will remain available for sale now that Peck was no longer alive. Yeremian said he plans to "keep his stuff in print. That is part of my responsibility in carrying on his legacy."

Peck's shining moment for comics historians, Comix: A History of Comics Books in America, 1971. Courtesy Dummy Archives.

Peck's shining moment for comics historians, Comix: A History of Comics Books in America, 1971. Courtesy Dummy Archives.But it was his 1971 work with Daniels on Comix that is likely to have had the biggest impact on members of the comics community, at least those of a certain age. The book was a thorough and serious look at the history of comic books and it arrived at a time when there were very few of its kind. Perhaps as a result, Comix seemed widely available at public libraries across the country and today's older comic artists and fans remember it fondly. And it was comprehensive, containing not only large sections on "funny animals," EC comics, and underground comix, but also pages about such forbidden, but informative, adult subjects like Tijuana Bibles. How it ever slipped by the eyes of so many librarians and ended up on the shelves is anybody's guess. My guess is that nobody in charge of such things bothered to actually look at it; in my public library, the book was located in the children's section. And for that, I remain forever grateful; I know that I'm not the only comics historian who can say that the book was life-altering.

From it's cover (a strange looking superhero character, swinging from a rope, with a banana emblem on his back, bopping a plane-flying pig in the snout) to its unexpected contents, Comix stood out in a somewhat baffling way. The cover, emboldened in bright yellow, red, orange and black colors, snuck a "Miss Under Stood" tag on the side of the plane. It also had a "Approved by Kids for Earth" stamp where the Comics Code Authority image appeared on comic books of the time. The back cover featured a slightly altered version of the weird house ad that ran on the back of Peck's Ghost Mother Comics. It was a history of comics books, to be sure, but one with a decidedly counterculture vibe.

The back cover of Comix. Courtesy Dummy Archives.

The back cover of Comix. Courtesy Dummy Archives."When I was a little kid, I used to take this book, Comix by Les Daniels, out from the library on a routine basis," the late Ed Piskor said in 2010. "That's where I first heard the name 'Mad Peck Studios' and it has totally stuck with me most of my life. I love that name."

In a 1971 holiday gift guide review, the New York Times called Comix "as good a history as has yet appeared, with a solid chapter on underground comics, and reproductions of complete episodes from Superman, Plastic Man, Batman, Captain America, Sub-Mariner, Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, The Fox and the Crow, Donald Duck and those terrible, awful, mind-rotting E.G, [sic] books (Crypt of Terror and Vault of Horror) which I couldn't get enough of as a youth, especially after Frederic Wertham's muck-raking Seduction of the Innocent put an end to them. To be given with discretion."

"Yeah, Comix was good," Peck wrote in Mad Peck Studios: A Twenty Year Retrospective. "Maybe a little too good. It's been stolen from every public library I've ever been in."

Perhaps it's time for a reprinting, though getting legal clearance (from Marvel, DC, Disney and others) to reprint those long, full color stories that ran in the 1971 edition will probably be harder today than it was 55 years ago. Yeremian says the book's mechanicals are likely among the materials Peck left behind. Along with a whole lot more. He is now charged with the formidable task of sorting through and cataloging Peck's massive archive of personal effects and historical artifacts. He is planning on "scanning and photographing everything that [Peck] created to share with the world. ... So I'm gathering up all this stuff and John Cook is going to help me organize it and we're going to start putting it on a madpeck.com website at some point so we can share his contributions with everybody."

It's no small task.

"There is no human being that has ever lived in this world who has a more thorough backlog of all of his work than [Peck]," he said. "I can tell you right now, he has every scrap of paper he's ever touched since high school. I mean, every scrap of paper. It's exciting and it's also daunting."

***

Peck was briefly married to Vicky (Oliver) Peck, a writer and collaborator of his who served as the basis for his I.C. Lotz character in many of his strips. Their marriage ended in the 1970s, but according to Yeremian, the pair remained in contact over the years. He is survived by his sisters, Marie Peck and Lois Barber.

An exhibit of Peck's work and tribute to his life is planned for this fall at POP, the Providence vintage shop and gallery space he frequented. An interview with Peck is scheduled to run in an upcoming issue of Kicks magazine.

I am planning on doing an in depth look at the life of the Mad Peck in a future issue of my comics history publication, Dummy.

A Peck eulogy for cartoonist Harold Gray that ran in Fusion after Gray's death in 1968. "It's a slick piece of work," Peck said of the piece. "But there's no future in doing illustrations for obituaries of famous cartoonists. How many die in any given year?"

A Peck eulogy for cartoonist Harold Gray that ran in Fusion after Gray's death in 1968. "It's a slick piece of work," Peck said of the piece. "But there's no future in doing illustrations for obituaries of famous cartoonists. How many die in any given year?"***

In the space below, a few people who knew Peck, or who just admired his work, share some thoughts about his remarkable life.

Peck with the Providence poster in an undated photo. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.

Peck with the Providence poster in an undated photo. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.Miriam Linna

musician/publisher, Kicks magazine. Norton Records

The Mad Peck always made me laugh with his astonishing record reviews delivered via his terrific comic strips. Getting a mention in a Mad Peck panel was better than anything. I interviewed him a few years ago for the still-simmering "new" issue of Kicks and I regret that he is not here to reminisce some more about Bridgeport and his early days as a foam-at-the-mouth doo-wop fan. The kid in that man never went away. His work on Earth has come to a finish but his humor and talent will continue to make us laugh. The Masked Marvel lives on!

Peck's high school graduation photo, ca. 1960. Courtesy Lois Peck Barber.

Peck's high school graduation photo, ca. 1960. Courtesy Lois Peck Barber.Jon B. Cooke

comics historian

Regardless of his Connecticut upbringing, John Peck was a particularly Rhode Island personality, educated by its premiere institution of higher learning — Brown University — and nurtured by the state's outré counter-culture, epitomized by the artists and creators who emerged from our other collegiate gem on Providence's East Side, the Rhode Island School of Design, which helped develop generations of quirky talents, including David Byrne and his band, the Talking Heads, film director Gus Van Sant, comics artists Walter Simonson and David Mazzucchelli, cartoonist Roz Chast, and graphic designer Shepard Fairey to name just a few. Rivaling Fairey's ubiquitous Andre the Giant/OBEY stickers adorning College Hill lampposts, the Mad Peck's iconic "Providence" poster was tacked to college dorm walls throughout the Ocean State. It was everywhere.

He was brilliant, acerbic, smart, reticent, funny, shy, cautious, and utterly ambitious with plan for fascinating projects, too many to count, and too many still that were left unfinished.

I was able to publish one article of his, a piece on comparing Mr. Coffee Nerves to the Crime Does Not Pay host, and there were plans for numerous other productions. One of my greatest regrets was not to conduct a career-spanning interview that he and I hoped to do together, but, though he is now passed, I will help promote his legacy to its rightful place in the history of underground comix.

His proudest achievement, it seems to me, was to co-produce the 1971 Comix: A History of Comic Books in America with his close pal and fellow Brown alumni, Les Daniels. When I put together a detailed, posthumous tribute for historian/horror writer/banjo player "Doc" Daniels, Peck revealed he was the writer of the Marvel Comics chapter and was likewise involved in all aspects of the book. That brilliant effort, the first history to treat equally super-hero, crime, horror, funny animal, and (especially) underground comix, is among the very best of its kind, and not only due to Les's smart writing but Peck's cheeky cover and overall design of the book.

I knew Peck for about the last 20 years and spoke to him infrequently. I'd say I earned his respect (no easy task that) with The Book of Weirdo, though he seemed to enjoy my magazine over the years, of which I always had comped him, in consideration for being one of the comix greats in his adopted state.

Peck, ca. 1980s. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.

Peck, ca. 1980s. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.Wayno

cartoonist

Like many of my generation, my first exposure to the mysterious name "Mad Peck Studios" came when the neon red and yellow cover of Comix caught my eye in a bookshop. Later, his record reviews in comic strip form made perfect sense to me as a kid whose only interests were comics and music. The combination of new drawings and text with collages of appropriated comic images and clip art was a welcome grubby alternative to Warhol and Lichtenstein.

From the late 1970s through the early 1980s, I was involved in several music fanzines. Among my duties was designing ads. I took inspiration from Peck's style and recognized its echoes in some Art Spiegelman comix and Bruce Carleton's punk-era ads for Trash & Vaudeville.

After a life of cultivated anonymity, it was fitting that a drawing by Drew Friedman was a prominent image accompanying Peck's New York Times obituary.

In 1974, Comix Book #2 (Kitchen Sink Press) ran a fake death notice announcement for Peck. The piece was written by Peck's Creem and Rolling Stone magazine colleague Richard Meltzer. "Meltzer had a wry and bizarre sense of humor, so, yes, he announced the death of Mad Peck as a joke," said publisher Denis Kitchen. "Virtually everything in his column was made up." Courtesy Denis Kitchen.

In 1974, Comix Book #2 (Kitchen Sink Press) ran a fake death notice announcement for Peck. The piece was written by Peck's Creem and Rolling Stone magazine colleague Richard Meltzer. "Meltzer had a wry and bizarre sense of humor, so, yes, he announced the death of Mad Peck as a joke," said publisher Denis Kitchen. "Virtually everything in his column was made up." Courtesy Denis Kitchen.Ariel Bordeaux

cartoonist

I didn’t know the Mad Peck, but I'll never forget my intro to "The Mad Peck" as a new resident of Providence. It was around 2002 or 2003, I was working at (one of) the comic book store, the Million Year Picnic's, short-lived locations on Thayer Street. I went out on a food run one day, and when I got back my friend and co-worker Susie G. was pretty worked up and upset about a customer interaction. She told me that a creepy jerk in a trench coat with long, yellow fingernails had yelled at her over some sort of petty dispute having to do with his Wednesday order. My memory is a bit fuzzy, but I do remember meeting him shortly after that — I think he came back into the store the same day or the next day. He was kind of a disheveled guy, and quite unpleasant, but I think we eventually straightened out his order. The manager, Paul L., knew him and filled me in. I'm sure we drew mean comics about him in the shared "log book" staff members kept at the counter.

His Providence poster is absolutely iconic in Providence, you see it all over town. It always struck me as a bit sad that no one seemed to know who the artist behind that poster was, but as a famously reclusive guy, maybe he kind of liked it that way — to be hiding in plain sight.

Mad Peck Studios, from Turned On Cuties (Golden Gate Publishing Company), 1972.

Mad Peck Studios, from Turned On Cuties (Golden Gate Publishing Company), 1972.Rob Tannenbaum

writer

John taught me how to build record shelves, and I still have two shelves I built under his purview. The deal was, he'd show you how to do it, but while you were building a shelf for yourself, you had to build one for him too. He'd show you how to do it and supervise you, but you had to buy the materials. A solid deal. I still have and use both shelves. And I'll never forget seeing him eat Elmer's glue while he supervised me. The shelves haven't buckled a bit in the past decades.

I met John at WBRU and our relationship did not get off to a good start. We were both in the programming office and he asked me to mark a record (write a small review on the front of it). I was in a hurry to leave and said no. He chuckled and said, "No drugs for you at Christmas." I don't recall what happened in the meantime, but it wasn't long before I worked the board for a couple of Dr. Oldie shows, which was a treat. He emailed me as recently as 2012 but I haven't been to Providence in years, so I didn't get a chance to see him. What an original.

The sign outside a thrift shop Peck operated for a time. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.

The sign outside a thrift shop Peck operated for a time. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.Chris Pitzer

AdHouse Books

I am probably the least qualified person to write a memorial for Mad Peck. The reason: I'm stupid. However, the book he worked on with Les Daniels, Comix: A History of Comic Books in America, is such a touchstone in my life that I felt I should at least try. Growing up in West Virginia in the '70s meant my access to comic books was somewhat limited. We had the spinner racks and the pawn shops, but both of those places took money, so you could always venture to the Public Library. Once I discovered Comix on the shelves, it became my favorite publication. (The only other choice at the time was Doonesbury collections, and I never really warmed to those.) So, here's the "stupid" part … of course I could figure out that Les Daniels wrote it, but graphics by Mad Peck Studios?!? What the hell did that mean? And for most of the rest of my life, I never knew who or what that meant. Just a few years ago on Spacebook (what my Dad would call it), I "friended" Mad Peck. And you know what? I still didn't really understand. However … I'm OK with that. Just being involved in the Comix book is enough for me to spend a few minutes putting my random thoughts down. I've encountered more than a few people who found this same book in their own library. What a legacy! Thank you, Mad Peck … who/whatever you were.

A 1971 letter from Harvey Kurtzman. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.

A 1971 letter from Harvey Kurtzman. Courtesy Robert Yeremian.Rick Altergott

cartoonist

When Mad Peck died suddenly at age 82, there was incredulity (and possibly jealousy) by some of his peers on social media because the New York Times gave him an extensive obituary in its pages. It was noticeable how this irked some, maybe because he was not seen as a true comics artist; his technique was more like transcribing and actually tracing imagery done by other hands.

That may be a fair criticism, especially if that were to be his sole contribution to the cartooning world. But he did a lot more than that, comics was just one of many lanes he travelled in.

His involvement in bringing out, Comix: A History of Comic Books in America would be enough for me to make him a notable and influential figure. Like many others, I had a copy of that book, at an early age, and it afforded me my first glimpses of what are now some of my favorite creators' work such as Crumb, Spain, EC, Warren.

That book's author, Les Daniels, had passed away before I had a chance to meet him here in Rhode Island. He is something of a legend in Providence. Like Peck, he was involved in many more enterprises than just Comix.

Both were also interested in daylighting obscure music and sharing that love with others in a kind of burgeoning fandom that they helped establish. I can imagine it was an exciting period for these guys with all kinds of interesting things happening to take in and promote. Peck, in particular, placed himself in the center of it all as a DJ, cartoonist, poster artist and publisher. But in a way that was always approachable and genuine; as a true fan himself.

I was lucky enough to meet Peck a couple of times before he passed. He was very kind and it was a real pleasure to talk with him, sharp as ever and still spinning new ideas and enterprises. I wish I had known earlier, but he had a kind of Phantom-like persona and I think he wanted it that way.

RIP Mad Peck

Drew Friedman's portrait of Peck from Maverix and Lunatix. Courtesy Drew Friedman.

Drew Friedman's portrait of Peck from Maverix and Lunatix. Courtesy Drew Friedman.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·