Greg Hunter | May 29, 2025

An old cliche cautions against judging a book by its cover; then again, a good detective studies every clue. And a reader inspecting Paul Auster’s The New York Trilogy: The Graphic Adaptation should consider the hints its jacket—a collaboration between the adaptation’s overseer Paul Karasik and book-design luminary Chip Kidd—offers about the book. Each of the adaptation’s cartoonists contributes a horizontal bar, forming a single figure out of the trilogy’s three protagonists. The talents involved are formidable: Lorenzo Mattotti and David Mazzucchelli alongside Karasik. The result is obvious, awkwardly executed, and a measure of what readers find inside.

An old cliche cautions against judging a book by its cover; then again, a good detective studies every clue. And a reader inspecting Paul Auster’s The New York Trilogy: The Graphic Adaptation should consider the hints its jacket—a collaboration between the adaptation’s overseer Paul Karasik and book-design luminary Chip Kidd—offers about the book. Each of the adaptation’s cartoonists contributes a horizontal bar, forming a single figure out of the trilogy’s three protagonists. The talents involved are formidable: Lorenzo Mattotti and David Mazzucchelli alongside Karasik. The result is obvious, awkwardly executed, and a measure of what readers find inside.

Locating the Paul Auster novels adapted for the new collection means looking to a tradition within detective fiction, one that seized the genre’s potential post-Edgar Allan Poe and Arthur Conan Doyle. The original New York Trilogy owes a debt to the existential detective, a genre archetype whose cases carry themes of choice, isolation, meaninglessness; not just murder but mortality. Dashiell Hammett introduced private detective the Continental Op in the decade after World War I; Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe stories began a decade later, in the years before US involvement in World War II. Together, these figures span a few decades of destabilized assumptions, characters whose searches resonate beyond the details of their cases.

George Simeon’s Maigret books offer a continental version of these efforts; in Maigret et le Clochard (1963), for example, investigating a beating leads to an encounter with an alien worldview. Fiction’s most notable investigators in the decades afterward don’t stray from existential concerns. The Harlem Detective novels of Chester Himes have violent and absurdist streaks; power is contested through swindles and identities are changeable. The Factory novels of Derek Raymond pose the detective as Sisyphus, persisting in the face of societal apathy. Parallel to these works, writers approached the detective from more experimental angles. Samuel Beckett’s Molloy (1951), for example, which Auster has praised directly, involves a private detective, Moran, in its study of death and identity, but Beckett departs from most of the genre’s prose conventions, subsuming elements of the detective story into a more formally challenging work.

Auster’s New York Trilogy falls in between these traditions. As with Beckett, Auster is willing to disrupt a reader’s notion of what his story’s reality is, although his trilogy does not go as far out as Beckett’s in its line-by-line prose. (Auster’s voice is straightforward, somewhat clinical, with occasional deliberate dips into the language of a genre potboiler.) The New York Trilogy also follows (more closely than Beckett’s work) the plot beats of a detective story, particularly the detective story as a story of descent. Auster’s characters chase clues into confusion, obsession, oblivion.

City of Glass, the first novel in Auster’s trilogy, arrived one year after Raymond’s first Factory novel, He Died with His Eyes Open (1984). Glass is a more face-value literary work than Raymond’s, but by some measures a less subtle one. Consider the original New York Trilogy as a Pompidou Center version of detective fiction’s philosophical architecture: self-conscious and demonstrative, though expertly assembled. Auster published the three novels in 1985 and 1986, before a collected volume in 1987.

Paul Karasik, with David Mazzucchelli, began adapting these works not long afterward. Their comics version of City of Glass arrived in 1994. The Paul Auster’s The New York Trilogy of 2025 reprints Karasik and Mazzucchelli’s collaboration alongside a Karasik and Lorenzo Mattotti adaptation of Ghosts and Karasik’s solo adaptation of The Locked Room. More time has passed between Auster’s original City of Glass and this completed graphic trilogy than the time between City of Glass and Raymond Chandler’s The Long Good-bye (1953). The new collection invites readers to gauge the remaining resonance of the existential detective, as the talents behind the adaptation continue the dialogue that Auster started. And, multiple Eisners between them, this group is not short on talent. But questions of purpose surround the graphic New York Trilogy—unrelated to any existential searching. Too often, adaptation in the book reads like an act without a motive.

***

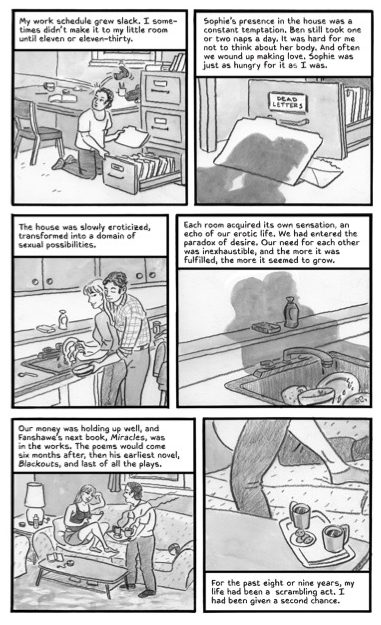

City of Glass follows Quinn, a writer called by someone seeking “Paul Auster, of the Auster Detective Agency,” and who impersonates “Auster” to take the client’s case. Later, Quinn encounters the in-story Auster directly, learning he’s not a detective but a writer himself. By that time, Quinn has devoted himself to shadowing Peter Stillman, a disgraced, eccentric academic. (Quinn’s client is Stillman’s son, also named Peter.) Quinn pursues the mysteries of the Stillmans beyond any advisable point, toward his own degradation.

City of Glass is a counterintuitive candidate for adaptation. Some of its concerns exist on the level of language: the elder Peter Stillman seeks to develop a new one, a more precise language to suit a fallen world, and has traumatized his son in his early efforts. Even without Auster’s metafictional self-insert, the original Glass would be a prose novel about prose. Yet its setting, puzzles, and Quinn’s decline provide plenty of opportunities for its adaptors.

A scene in which Quinn waits for the elder Stillman at a train station exemplifies Mazzucchelli’s contributions. On one page, a straightforward but elegant series of panels conveys Quinn’s environment and mission before the shift to an efficient, adventurous bottom tier. The sound effects at bottom convey all of the following: Quinn’s sensory experience; Stillman’s idiosyncratic philosophy of language (with the familiar onomatopoeia of CLACK followed by an alien phrase, subtly distinguished by variations in lettering); and the trauma of Stillman’s son, as well as Quinn’s identification with his client (as Quinn’s face gives way to a sketchier rendering of primal pain).

Auster writes the same moments like so:

At six-thirty he posted himself in front of gate twenty-four. The train was due to arrive on time, and from his vantage in the center of the doorway, Quinn judged that his chances of seeing Stillman were good. He took out the photograph from his pocket and studied it again, paying special attention to the eyes. [...] Once again, however, Stillman’s face told him nothing.

The train pulled into the station, and Quinn felt the noise of it shoot through his body: a random, hectic din that seemed to join with his pulse, pumping his blood in raucous spurts. His head filled with Peter Stillman’s voice, as a barrage of nonsense words clattered against the walls of his skull.

Karasik and Mazzucchelli display a judicious sense of what comics do well and of the artist’s specific strengths. Where Auster’s prose includes hard-boiled rhetorical flourishes about pumping blood and a clattering skull, Mazzucchelli adds density to his panels with spot blacks and frames his figure against an oppressive urban environment—not a precise phrase-by-phrase trade, but an effective one.

Later in the scene, Quinn must identify Stillman by a photograph years out of date. He finds an additional challenge: two possible Stillmans enter the station, both resembling older versions of the man in the photo. Here again, compare Karasik and Mazzucchelli to Auster:

Directly behind Stillman, heaving into view just inches behind his right shoulder, another man stopped, took a lighter out of his pocket, and lit a cigarette. His face was the exact twin of Stillman’s. For a second Quinn thought it was an illusion, a kind of aura thrown off by the electromagnetic currents in Stillman’s body. But no, this other Stillman moved, breathed, blinked his eyes; his actions were clearly independent of the first Stillman. The second Stillman had a prosperous air about him. He was dressed in an expensive blue suit; his shoes were shined; his white hair was combed; and in his eyes there was the shrewd look of a man of the world. He, too, was carrying a single bag: an elegant black suitcase, about the same size as the other Stillman’s.

Quinn froze. There was nothing he could do now that would not be a mistake. Whatever choice he made—and he had to make a choice—would be arbitrary, a submission to chance. Uncertainty would haunt him to the end. At that moment, the two Stillmans started on their way again. The first turned right, the second turned left. Quinn craved an amoeba’s body, wanting to cut himself in half and run off in two directions at once. “Do something,” he said to himself, “do something now, you idiot.”

The passage above captures Quinn as an existential detective; his choice is arbitrary yet freighted with consequence, a true crisis of meaning. Comparing prose to cartooning here also shows how much Mazzucchelli does in four panels, and what Karasik and Mazzucchelli understand they can lose. To adequately draw the similarities and differences between the two Stillmans would be easy. Mazzucchelli’s page goes further; in his staging, the two figures jockey unknowingly for Quinn’s focus, with Quinn stuck at a crossroads, receding in the face of an unexpected complication. Both pages above find the City of Glass adaptation at its best, with a controlled tone, graceful compositions, and a restraint that’s sometimes missing—not just in Glass but in the next two volumes.

Karasik and Mazzucchelli use visual metaphors often throughout Glass, especially during moments of heavy exposition. As a character describes the younger Stillman’s trauma—nine years of confinement by his father—readers see a white grid on a black panel, evoking the locked room and its covered windows; a stack of calendars, evoking the duration of the stay; and panels mimicking safety signage to evoke the young Stillman’s rescue and his father’s sentencing. Such moves are logical and, as the story advances, wear out their welcome.

An inflection point comes around two-thirds of the way through the graphic Glass, as Karasik and Mazzucchelli repeat an early image of a thumbprint turning into a maze. It’s clever visual shorthand—crime-scene iconography leading to more profound searching—diminished by repetition. At their least effective, these formal gambits work against the controlled tone of Auster’s prose. Take a page in which Quinn, now excessively committed to surveilling the elder Stillman, becomes further removed from fellow humans and less differentiated from his city. The brick person, the crying building—these images solve the problem of how to compose a page about a character sitting and watching, but tilt the story toward silliness in doing so.

Near the end of City of Glass, Quinn, undone by his relentless surveillance of Stillman, enters the man’s apartment to find it empty. The scene has the quality of metaphor—perhaps beyond the adaptors’ intentions. The best pages of the graphic Glass showcase Mazzucchelli’s gifts for composition and mood. Such pages aren’t mutually exclusive with the adaptors’ conspicuous formal gestures; many are fairly adventurous. But the self-conscious formalism of other scenes affects a busyness that, paradoxically, makes the adaptation feel empty.

***

The passage of time has likely blunted the impact of Karasik and Mazzucchelli’s City of Glass adaptation, even if a 2025 edition asks for 2025 eyes. A year removed from Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics (1993), the formal flourishes of Glass might have read like a revelation. The work also compares favorably to many other prose-to-comics adaptations (an area of the medium with a skewed respectability-to-quality ratio). Karasik rejects an assumption, common in these works, that illustrating the motions of a novel’s plot is sufficient. He understands that a novel’s effects come not just from incident but from language.

The best-case scenario for adaptation into comics has to follow this understanding, to move beyond substitution (of speech balloon for quotation marks, of drawn motion for written motion). A measure of success might be an image so potent a reader can’t imagine a written referent, one that seems impossible to reverse-engineer into prose. Lorenzo Mattotti is as poised as anyone to meet this challenge, and has chased it before in works such as his vibrant 2003 take on Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Adapting The New York Trilogy’s second book, Ghosts, he’s a match for the material too, providing dark, coarsely textured settings and figures that resemble mid-century sculptures. He’s also victim of and accomplice to Karasik’s errors in judgment, producing a number of heavy-handed visual metaphors across the book.

Ghosts repeats and rearranges many plot points and motifs from City of Glass. This time, a private investigator, Blue, surveils a man named Black at the bidding of a man named White. Uncertain about the purpose of this work, Blue nonetheless commits, falling toward obsession, then ruination, along a trajectory similar to Quinn in Glass. Blue vacillates between wishing for violence against and connection with his target, his identity undermined by the process of watching. Auster’s character names make it clear he’s working in archetypes, and although he grounds this novel in the 1940s, Mattotti’s contributions emphasize its otherworldly qualities.

Auster’s conversation with the genre is most compelling throughout Ghosts. It’s intuitive to think of the detective as a watcher or a seeker, but Auster finds layers within these ideas. One scene of Blue observing Black draws a parallel between the work of detection and the mind’s more reflexive meaning-making:

The beating of his heart, the sound of his breath, the blinking of his eyes—Blue is now aware of these tiny events, and try as he might to ignore them, they persist in his mind like a nonsensical phrase repeated over and over again. He knows it cannot be true, and yet little by little this phrase seems to be taking on a meaning.

Surveillance here leads Blue to a heightened pattern recognition—with his possible conclusions no more valid for it. The meaning-making we do is fundamentally fraught, the scene suggests.

Further into watching Black, Blue abandons much of his earlier life, and “discovers the inherent paradox of his situation. The more deeply entangled he becomes, the freer he is.” As with Quinn of the previous book, there is a lift before the character’s descent, a freedom through self-erasure. A later moment in Ghosts complicates this, turning the status of patsy into an existential dilemma:

It seems plausible to him that he is also being watched, in the same way that he has been observing Black. If that is the case, then he has never been free. From the very start he has been the man in the middle.

Karasik and Mattotti adapt these and other scenes mostly as illustrated prose. Passages from Auster’s novel usually appear one or two at a time, accompanied by a single image. Less often, Mattotti works in a more traditional cartooning mode. Even more rarely, the graphic Ghosts includes Auster’s prose with no accompanying image.

Mattotti is steady but versatile throughout his pages, a match for the story’s most outlandish and most subdued moments. When Blue meets his client White, the latter in some state of disguise, Mattotti captures the scene’s mixture of weirdness and menace. Some of his most effective illustrations are his most straightforward, including a look at Blue watching Black leave footprints in the snow, a tree of threatening branches to the right of both men, neither one’s face visible. There is a hushed potential here, an expert evocation of the calm before the storm.

For all this, the graphic Ghosts is a limited work, its component parts functioning uneasily together. The adaptation has a rhythm different from most comics, due to its illustrated-prose pages—except when it is comics, or when it is mostly prose. The result is disjointed in the immersion it offers a reader. And a reader, distracted, may start pondering material explanations for this (contractual terms, production-cycle efficiencies, etc.), because there’s no clear aesthetic one.

Pages with a single illustration challenge the adaptors to distill Auster’s prose to an image that’s apt but not obvious. Despite the gravity Mattotti gives these pieces, the results are sometimes clunkers. A page in which Blue writes to his mentor (retired to Florida) for guidance, and finds his mentor’s response dissatisfying, shows Blue literally drowning as his mentor dawdles in a boat nearby. The image has the texturedness and restraint characteristic of Mattotti’s work, but offers no room for interpretation. The graphic Ghosts holds the reader’s hand through most of its metaphors, making their meanings impossible to miss. It’s a significant departure from the steely remove of Auster’s prose.

These metaphors are not always confined to one page. Sometimes Karasik and Mattotti sustain sequences across a few pages, a reasonable approach in theory that can work against the adaptation. As with the thumbprint maze of Glass, images here lose their potency through repetition. A strong early page sees Blue shaking hands with White while levitating above a trap door, due to fall in time. It’s foreboding and effective, down to the pinstripes of Blue’s suit anticipating his vertical trajectory. The next page depicts his fall, with Blue tumbling before the backdrop of a typewriter page. The page after that shows Blue dropping next to his bed, in an innocuous, compositionally sound image that still lands far from the intrigue at the start of the sequence, with broad body language and little for a reader to consider.

By the end of Ghosts, a complex picture emerges of Karasik as the trilogy’s chief adaptor. He sees the necessity of visual language in adapting prose—certainly in order to achieve a similar impact. (In going beyond the most literal-minded options, he stays ahead of most prose-to-comics adaptors.) He’s also better at casting than directing. In Mazzucchelli and Mattotti, he has collaborators who excel at tone, creating compositions rich with suspensefulness. Yet the adaptations read as if Karasik can’t fully trust tone to carry a scene; even a groaner of a metaphor often wins out instead. And so readers find works of insight and invention that are also visually overdetermined and seem oddly insecure.

***

The adaptation of The New York Trilogy’s final section, The Locked Room, provides further evidence for Karasik as the primary culprit for the missteps of the first two stories. As adaptor and cartoonist here, he repeats the excesses of the previous adaptations, while trailing Mazzucchelli and Mattotti on the level of craft. His functional, unassuming cartooning (a fit for venues such as Fantagraphics’ Fletcher Hanks reprint collections, in which Karasik documents himself exploring the history of the golden-age superhero artist) suffers from proximity to Mazzucchelli and Mattotti. And while the essence of a detective story is in the searching, an anticlimax is still a crime.

The Locked Room returns to the premise of a writer taking the role of detective. The story’s lead character (name withheld) learns a fellow writer and childhood friend has disappeared. The friend, Fanshawe, has left him the duty of being Fanshawe’s literary executor. After accepting this responsibility, the lead also finds himself becoming involved with Fanshawe’s wife and acting as father to his son. (Doubling, a motif throughout the trilogy, intensifies here.) After shepherding Fanshawe’s manuscripts to book-world success, the lead agrees to write a biography of Fanshawe—having learned that Fanshawe still lives, and will kill to preserve the distance between them. As with City of Glass and Ghosts, the central character’s investigation of another figure leads him to obsession. Auster again uses this investigation to pair concepts such as connection and destruction, identity and erasure, and freedom and obligation, then unsettles the lines between them. Locked Room also accounts, more or less on plot level, for the overlap and repetition across the three stories.

More often than in Glass or Ghosts, blemishes in The Locked Room obscure its pleasures. Its pages feature a drab gray ink wash rather than the dynamic contrasts of the Mazzucchelli and Mattotti sections. The more ornate formalist sequences have the effect of a dad joke without humor, an elbow bump to the reader’s side to ensure they get a page’s meaning. One sequence sees the novel’s lead, after committing to read Fanshawe’s manuscripts, literally seated inside an enormous trunk full of stories. “There were over a hundred poems, three novels, and five one-act plays,” and the scope of the endeavor is impossible to miss. Another sequence features a variation on the maze metaphor, this time with the lead “looking for a way to begin” the writing of Fanshawe’s biography, and so walking the labyrinth of his own mind.

More so than in Glass or Ghosts, Karasik can stretch a metaphor to the point of silliness too. As the lead expands his research into Fanshawe’s life, readers see him digging for answers, shovel and all, and uncovering sources in a former classmate and former shipmate. This sequence ends as a tiny lead character leaps from a giant shovelhead into the entrance of a travel agency. The text of Locked Room is excerpted at length in captions throughout the sequence, and Karasik’s images are discordant with Auster’s restrained prose in such moments. Never in the first two volumes does the adaptation undermine itself to this degree.

A similar miscalculation occurs as the lead meets with Fanshawe’s mother, sleeping with her in the culmination of a boozy lunch. First, concerning women in these stories: it’s all pretty bad. Auster’s novels transport, unreconstructed, the misogyny common to hard-boiled crime fiction, not brazenly but consistently. Women appear as bodies, not characters, and Karasik et al. reproduce the novels' stance. There’s perhaps less to say on this topic than about the complexities of adaptation, if only because the stories do so little to complicate it.

Anyway, the lunch: as the lead character and Fanshawe’s mother grow intoxicated, readers find some compelling imagery which, in a pattern that will be familiar by this point, builds on itself until the sequence topples. Speech balloons rise and merge, floating upward and taking the lead character with them; he rests on them, losing his constitution and beginning to precipitate into the woman’s wine glass. It’s a weird, good page, notable for how much work the artist lets shape and contour do. Then, under Karasik’s heavy hand, pages afterward see the lead fully transformed into a human wine drop, a liquid man-torpedo, falling toward Fanshawe’s mother’s lips. The sequence reaches for the absurd and grasps the merely goofy.

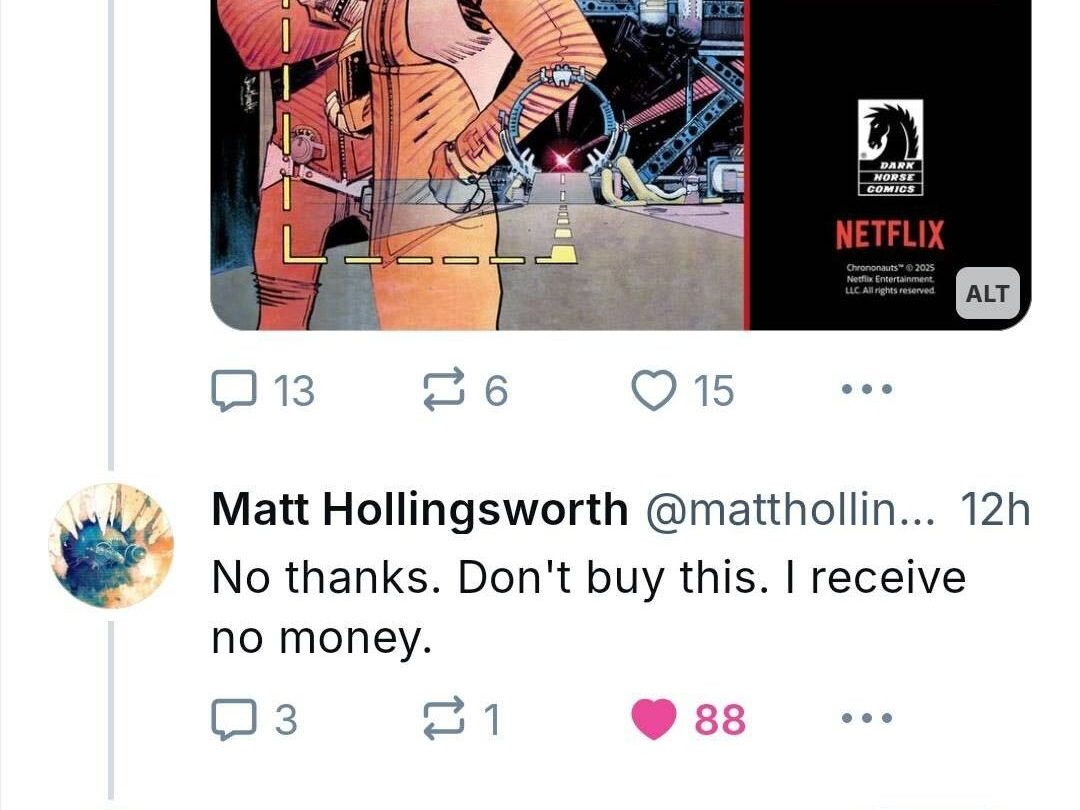

The question of why intensifies across a reading of The New York Trilogy: The Graphic Adaptation. Why a complete adaptation three decades after the graphic City of Glass, why the inconsistent approach in the Mattotti section, why all the cheap-seats semiotics? Market logic could be a red herring, but the idea resolves many questions around the book; the New York Trilogy adaptation as a safe bet for a house in the business of best-sellers, easy to market as a masterpiece on arrival. And if public opinion doesn’t break this way in the years that follow, book buyers will have already visited the empty room.

Auster’s original novels explore the existential detective tradition by making its elements as overt as possible, celebrating the body by showing its bones. His protagonists feel the gravity of choice, the effects of isolation. Death is never far off, both as a threat and an animating force. Each case, again, is a crisis of meaning. But that’s different from a work that lacks true purpose.

All images are from Paul Auster's The New York Trilogy: City of Glass, Ghosts, The Locked Room. Credit to author Paul Auster, and illustrators by Paul Karasik, Lorenzo Mattotti and David Mazzucchelli. Pantheon Books, 04/08/2025

English (US) ·

English (US) ·