Photo of Josh Pettinger by Chris Anthony Diaz.

Photo of Josh Pettinger by Chris Anthony Diaz.There’s an old saying about London buses; “You wait ages for one, and then two come along at once.” And the same could be said for books by British cartoonist Josh Pettinger. Since emigrating to the US in 2014, Pettinger has spent the past decade toiling away on the margins of the comics scene, publishing eight issues of his series Goiter and a bunch of one-shots featuring his character Tedward for a devoted and steadily growing audience. But all of a sudden his career seems to have shifted into a higher gear, with two major collections appearing in quick succession. In 2024 Floating World published an (almost) complete edition of Goiter, the French version of which made the Official Selection at that year’s Angoulȇme Festival. And then, less than a year later, Fantagraphics compiled all the Tedward stories into a single volume, finally bringing Pettinger’s signature blend of dry, absurdist humor and highly distinctive cartooning to the wider audience it deserves. Meanwhile, he’s also been pursuing an ongoing collaboration with his close friend Simon Hanselmann, both in print (in 2023’s Werewolf Jones & Sons Deluxe Summer Fun Annual) and on YouTube, with Manga Chat, their semi-regular look at the indie comics scene.

Although Pettinger is a highly accomplished humorist (and in case it needs emphasizing, his comics are very funny indeed), the surface comedy of his work often conceals much darker undercurrents. His stories are populated by a gallery of loners and misfits leading precarious lives, overwhelmed by forces outside their control, and drawn into shadowy places which border on nightmare. From hapless ventriloquist Henry Kildare, who ends up accused of child murder after an out-of-town gig, to Michael, the weak-willed protagonist of Amazon-baiting dystopian fantasy Victory Squad, these are people stymied by their own apathy and existential ennui, trapped in a universe which hovers somewhere between indifference and outright hostility. And then there’s Tedward, a perfectly realized comic character (and self-styled “old-fashioned guy”) whose unfortunate blend of social awkwardness, innocence, and idiocy constantly propels him into unsettling situations involving sex trousers, cum parties, and papier maché modeling rivalry.

With the first issue of his new series, Pleasure Beach, not long off the press, it seemed like an ideal time to catch up with Pettinger and get some idea of what makes him tick. This wide-ranging conversation touches on everything from his formative years in the UK and his early comics work to the economics of self-publishing and the delicate balance between autobiography and fiction that underpins much of his work. With a self-deprecating sense of humor and deep-rooted perfectionism, Pettinger comes across as an intensely self-critical artist, dedicated to improving his craft with every new project. At times, he might even give the impression that none of his work is even worth reading. But rest assured, nothing could be further from the truth.

This interview was conducted in two sessions via Zoom in July 2025. It has been edited for clarity.

Early years

RICHARD POUND: Let’s start right at the beginning. I know you were born on the Isle of Wight, but do you want to give a quick description of what (and where) that is for anyone who isn’t familiar with UK geography?

JOSH PETTINGER: It’s an island off the south coast of England. I believe it’s about eight by twenty-one miles, so it’s very small, kind of cut off a little bit, very rural, and a little bit backwards. It felt like it was ten years behind with fashion, culture, and that sort of thing. It was very stifling. It’s also known for having the three major prisons in England.

Parkhurst being one of them, right? [Note: Long known as one of the UK’s most notorious and violent prisons, Parkhurst’s famous inmates have included serial killer Peter Sutcliffe (‘The Yorkshire Ripper’), Moors Murderer Ian Brady, and East End gangsters the Kray Twins.]

Yeah, Parkhurst, Camphill, and Albany prisons. So, in terms of career options when I was growing up, it was basically a choice between servicing the tourists or being a Corrections Officer.

The island is only about two miles from the mainland, though, so it’s not like the Shetland Islands or something. Not too remote?

No, I mean there’s a ferry, but it was quite expensive when I was growing up, so the mainland felt pretty inaccessible.

So there was a real sense of isolation when you were young?

Yeah, definitely. I grew up on a council estate, which is a kind of government housing. And we lived in probably the roughest part of it. Our estate was like the punchline for people there, you know? “Oh, that person’s from Pan Estate!” It was the rough, quite grimy part of the Isle of Wight. One thing I really remember growing up was, where I went to school there were two sheds for the parents to wait when they picked you up from school, and one was just quite normal middle-class kinds of people, and then the shed where I got picked up was all mums smoking cigarettes in the playground. Although one thing that always stuck with me was that there was so much laughter coming out of that shed and not so much from the buttoned-up, middle-class shed. The class divide was very obvious on the Isle of Wight. And I was very much on the bottom end of it.

What did your parents do there?

My dad worked various manual labor stuff. The longest job I remember him having was working on cranes, but I never really, fully knew what he did. My mum was a stay-at-home parent until my Dad died when I was 17, and then she worked at a clothing store as a manager.

Was your father an absent figure when you were young? It’s interesting that quite a few of your characters, like Tedward or Beryl in Pleasure Beach, have mothers but not fathers. Is that absence of father figures related to your own experience?

I wouldn’t say absent, but he worked away a lot, so he was never in the house that much. He had to do long stretches in other places because the economy for manual laborers was so bad. It was like that TV show, Auf Wiedersehen, Pet, where they all had to go and work in Germany for a year or something. He ended up dying in an accident at work. He drowned while digging wells. So I feel like I have a complicated relationship with what a father is, as opposed to what a mother is, and perhaps when I create a character, that’s territory that I’m either not equipped to explore or just don’t want to explore. The only way I have explored it is by writing those stories in the Werewolf Jones book with Simon. Because I’m doing it with his character and his world, I have a layer of distance, so I did end up putting some stuff in there that was quite personal to me. In those stories, it doesn’t specify who wrote what, so I used that as a way to say some stuff about my relationship with my Dad.

Working on that book in particular, I guess you were forced to deal with the idea of a father figure. It was unavoidable.

Exactly. And I could also do it in a funny way. Without that distance, I don't think I could have done it.

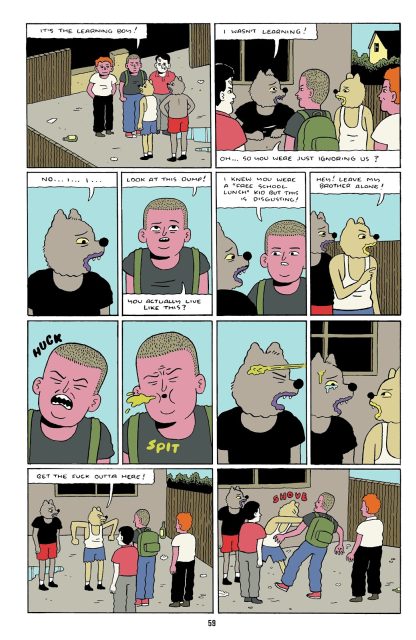

From "Bully," one of the Pettinger-drawn stories from Werewolf Jones & Sons Deluxe Summer Fun Annual.

From "Bully," one of the Pettinger-drawn stories from Werewolf Jones & Sons Deluxe Summer Fun Annual.Were your parents born on the island as well? Does your family have a long history there?

They actually don’t. My dad was from Birmingham, and my mum was from London. I think they moved there as very young children. We had family there, but we didn’t have roots or anything. But the goal was always to move away. For as long as I can remember, the main goal was to get off that island.

What kind of things did you do for amusement or distraction?

Basically I just withdrew into drawing at a very young age. As long as I can remember, from maybe seven years old or something, drawing has been the main thing I’ve done. But I also played in punk bands when I was a teenager. There was a bit of a local music thing going on. But mostly it was just drawing. I have weird memories of growing up, though. On one hand, it was quite a violent place. It felt like, just leaving the house, the chances of being beaten up were really high for some reason! I was constantly getting in, well, I wouldn’t call them fights, but I was just always getting beaten up. It felt like being indoors drawing was the safer option. But then, on the other side of my house, there were fields and trees as far as you could see, so I also had this weirdly idyllic aspect to my childhood, hanging out in forests. Although I remember wandering through this big, enchanted, magical forest, and then seeing two teenagers having sex in a hammock, or somebody completely fucked up on drugs. Those are early memories of mine.

So even the idyllic side of it was tainted.

Exactly.

What about school? Was that any better, or was it a nightmare too?

It was good up until it wasn’t. I was on the soccer team, kind of popular, and then one year I was suddenly the smallest kid, and subjected to quite horrible bullying, so it became a much more threatening, horrible place. All my memories of high school are quite horrible. So I was just withdrawing into art and finding ways to express myself through music or drawing.

Does Bully, one of the stories you drew for the Werewolf Jones & Sons Annual, reflect that experience to some degree?

Simon actually wrote the first half of that story. On that book, we had bits and pieces of ideas and it was like, “I’ll go finish this idea and put my spin on it.” But that one was based on a very specific experience of his; his mum chasing down a bully and threatening to kill or stab him (laughs). But I drew that one because I could relate to it. There’s also the thing of them getting bullied because they’re poorer kids, and I put that in there because it was a personal experience. The schools nearest to my house had really bad reputations, but my mum wrote to schools further away saying, “My kids are really smart, they deserve to go to the good school, blah, blah, blah.” So she managed to get us into what were still regular state schools, but closer to better neighborhoods. But that turned out to be a double-edged sword because suddenly we were surrounded by kids who, like I said before, see where I’m from as a punchline. But it was still preferable to where I would’ve ended up otherwise.

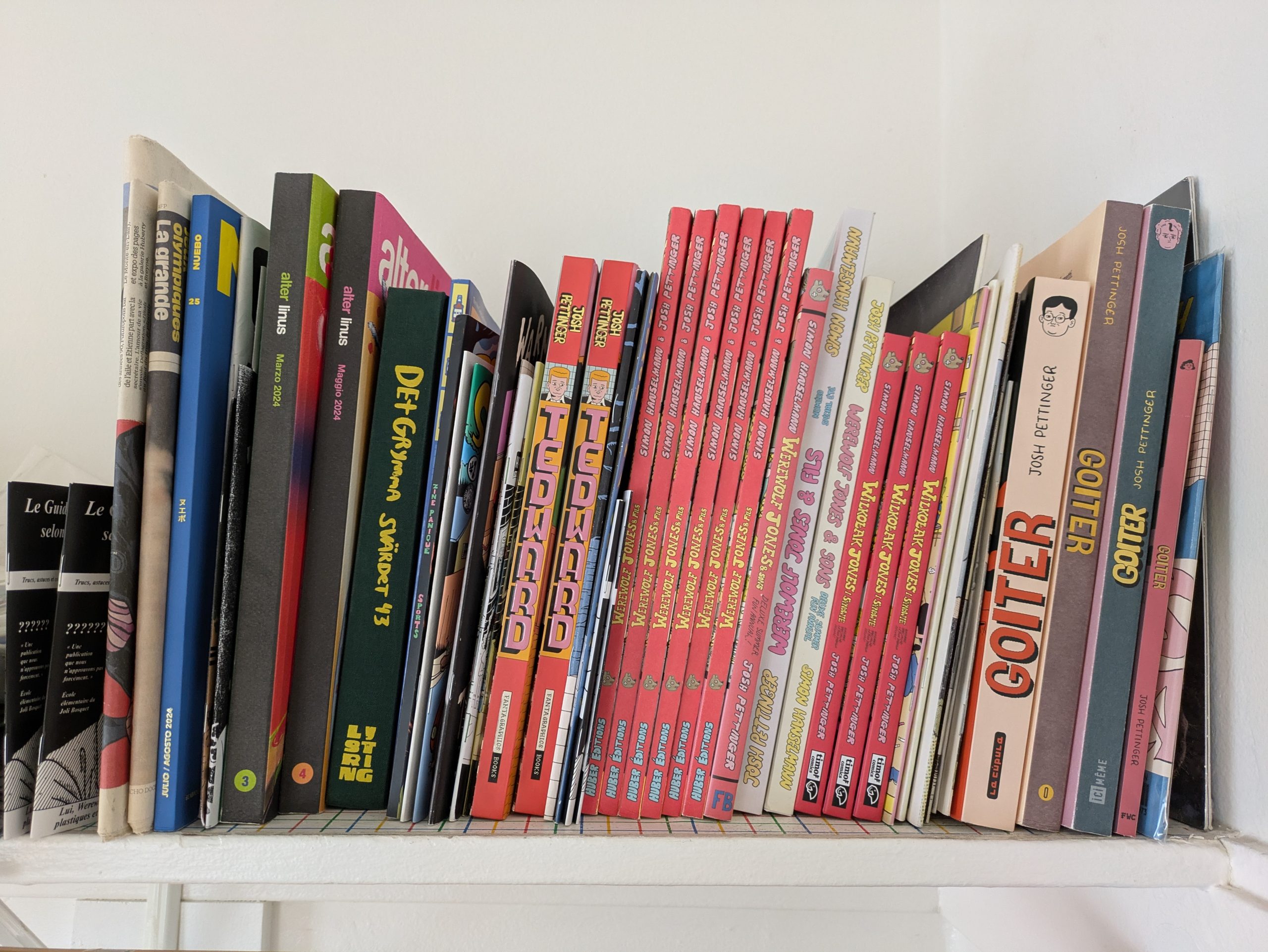

Photo of Pettinger's body of work to date provided by the cartoonist.

Photo of Pettinger's body of work to date provided by the cartoonist.Comics

So, amongst all this turmoil, what was your first exposure to comics? You said you’d been drawing from a young age, but was that a response to seeing comics, or were you drawn to comics because you loved drawing?

It was more like cartoons, specifically those early Simpsons episodes. I didn’t have much access to comics growing up. There was one store near me, I believe it was called Musical Sounds, which sold Nu-Metal T-shirts, wrestling DVDs, and a few comics. For some reason they had every issue of Orion and Manhunter, so I’d go in and constantly buy those and just always be disappointed. I wanted them to be so much better than they actually were. I just hated them so much, but I kept buying them because there was something about the medium. I loved having them, but I just hated reading them!

[Laughs.]

Do you remember the Simpsons comics in the larger format?

Sure, the British magazine-sized editions.

Yeah. Well, my older brother’s friend had all the issues in the smaller American format, and there was something so cool about that to me, and I became obsessed with them. My grandmother also had a lot of old Beano and Dandy annuals, and I loved looking at those and re-drawing them, but there was also something really depressing about them because there were, like, kids getting beaten up by their teachers. It was all very seventies, very bleak and horrible.

A bit too close to home?

Exactly. And the other thing I was really into as a kid was Raymond Briggs. I really liked Fungus the Bogeyman, and we also had Unlucky Wally. There was one bit I remember where he’d joined the army, and they pulled down his trousers, cupped his testicles, and made him cough. I just remember being so horrified by that as a kid, but it also made such an impression on me artistically; this horrible, depressing image that scared me. It was like, “this is what adulthood is!?”

[Laughs.] Those random moments of indignity. And most of the characters you’ve created have to suffer through those. It’s kind of a theme in your work.

Yeah, I think it really made an impression on me. Weirdly, my biggest influence is probably that panel of him having his testicles cupped! But then, when I left the island, I went to university in London. And one day I walked into Forbidden Planet and discovered all these American comics, independent comics, and the whole world opened up.

What were the first things you came across?

The first thing I bought there was Pussey! by Dan Clowes, then Paying for It (Chester Brown), and My New York Diary (Julie Doucet). After that, it was just a flood of everything. I just started reading through the history of it all, and buying every book.

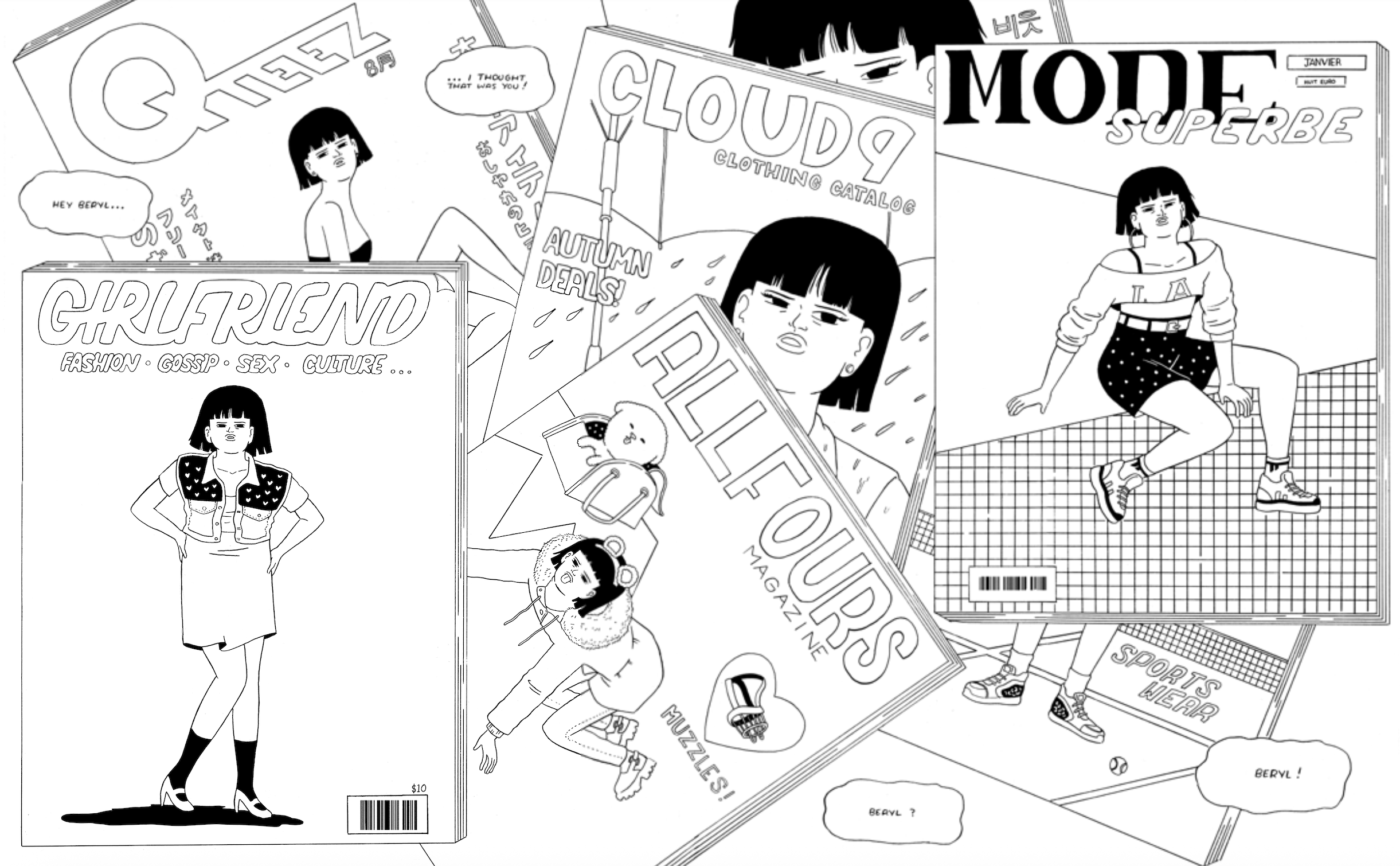

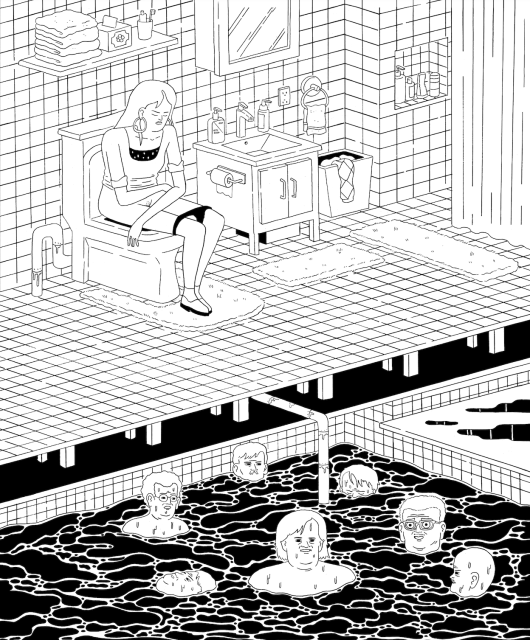

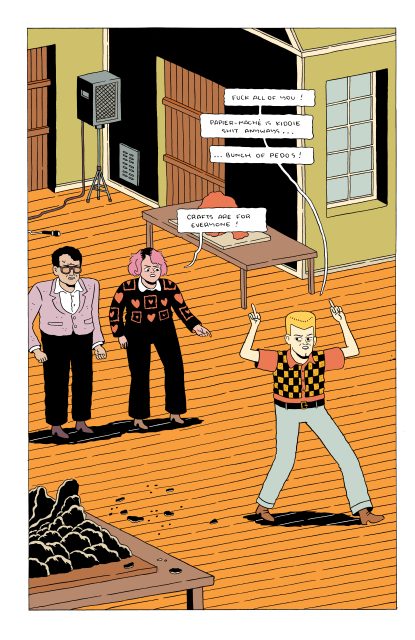

Sequence from Pleasure Beach.

Sequence from Pleasure Beach.Like a kid in a candy store.

Yeah. I was studying animation at the time, and my experience of comics was still so limited. But as soon as that opened up, I almost completely lost interest in animation, and everything was suddenly like, “I’m going to make comics.” But I still had to finish that degree.

Where were you studying?

The University of Westminster.

So that would have been three years of animation?

Yeah, although I ended up doing four years. I failed my dissertation and had to go back and finish that.

Was that back when you could still get a student grant, or did you have to work your way through?

I think I was in the last year that could still get them. For any American readers, in England you used to be able to go to university for three years and not pay anything. Not only that, but you’d be paid to live, basically. So I felt very lucky about that. Coming from where I did, and the class that I came from, opportunities to move to the big city, meet like-minded people, and expand your world in that way, just didn’t exist outside of going to university. I really feel for younger people these days. It’s almost like nobody who comes from a working-class background is going to be able to make it as an artist.

What year would this have been?

2008 or 2009. Around the same time, I started discovering what was happening on Tumblr, and suddenly got excited by people like Matt Furie and Alex Schubert. But that may have been a few years later. It’s all kind of a fog when it comes to time frames and stuff.

The other obvious influence on your work is British TV comedy, especially from the ‘90s onwards.

Yeah, I was really into collecting DVDs of comedy. Chris Morris, Alan Partridge, Peep Show … British comedy was so massive to me at the time. The Day Today was really big, and Jam. My first series, Goiter, was actually named after a special feature on the Jam DVD.

Jam is pretty unforgettable. It was one of the darkest shows ever to appear on British television, but also one of the funniest.

Some of it was quite nauseating. Good stuff!

So, after four years in London, did you move back to the Isle of Wight before you left for the States?

No, I moved straight from London to Chicago and lived there for seven years. That’s where I started drawing comics. I drew maybe the first six issues of Goiter there. And then, right at the beginning of the pandemic, I moved to Los Angeles, then to Philadelphia two years after that, and I recently moved again to San Francisco.

So you’ve been over there for more than a decade now?

Yeah, I think I moved in 2014. Ten years later, it feels like home. It’s all I’ve really known in my adult life.

What kind of jobs were you doing when you first got to Chicago, before you started making a living from comics?

First I worked in the stock room at Gap for two years, folding t-shirts. A point of pride with me, even now, is that I’m still really good at organizing my drawers and folding stuff. To this day, my clothes drawer looks like a storefront [Laughs.] Then I worked as a server in restaurants, which I would actually recommend to any artist who needs to have a job. It was really good money, and so flexible. I was working four days a week, on five-hour shifts, and more than getting by. I’d work five hours and then have four hours to draw. And the days I wasn’t working, I could draw for eight or ten hours. It’s the best possible job for a cartoonist. The whole of Goiter was basically drawn while working in restaurants.

What about animation? After studying it for three or four years at university, have you ever done any professional work in the field?

Yeah. I started making a living from comics at the beginning of the pandemic, so five years ago now, but I’ll still do maybe one animation gig a year as an extra income stream. Nothing I’d be desperate for people to see though! I worked on a music video for the band Journey, did something for Notion, a tech company. Nothing for television, just weird little things like that here and there to keep things afloat.

It must be quite time-consuming when you’re trying to focus on the comics.

It depends. Sometimes you have such a tight deadline that you can get the job done in one intense burst of work that doesn’t take up too much time throughout the year. But everything else has to stop. I can’t do comics at the same time. I just have to go hard on that project for a month or whatever. So I try to take as few of those gigs as I possibly can. They’ve always been helpful, but it’s just not really my thing. Making comics is like playing with action figures, but animation feels like work.

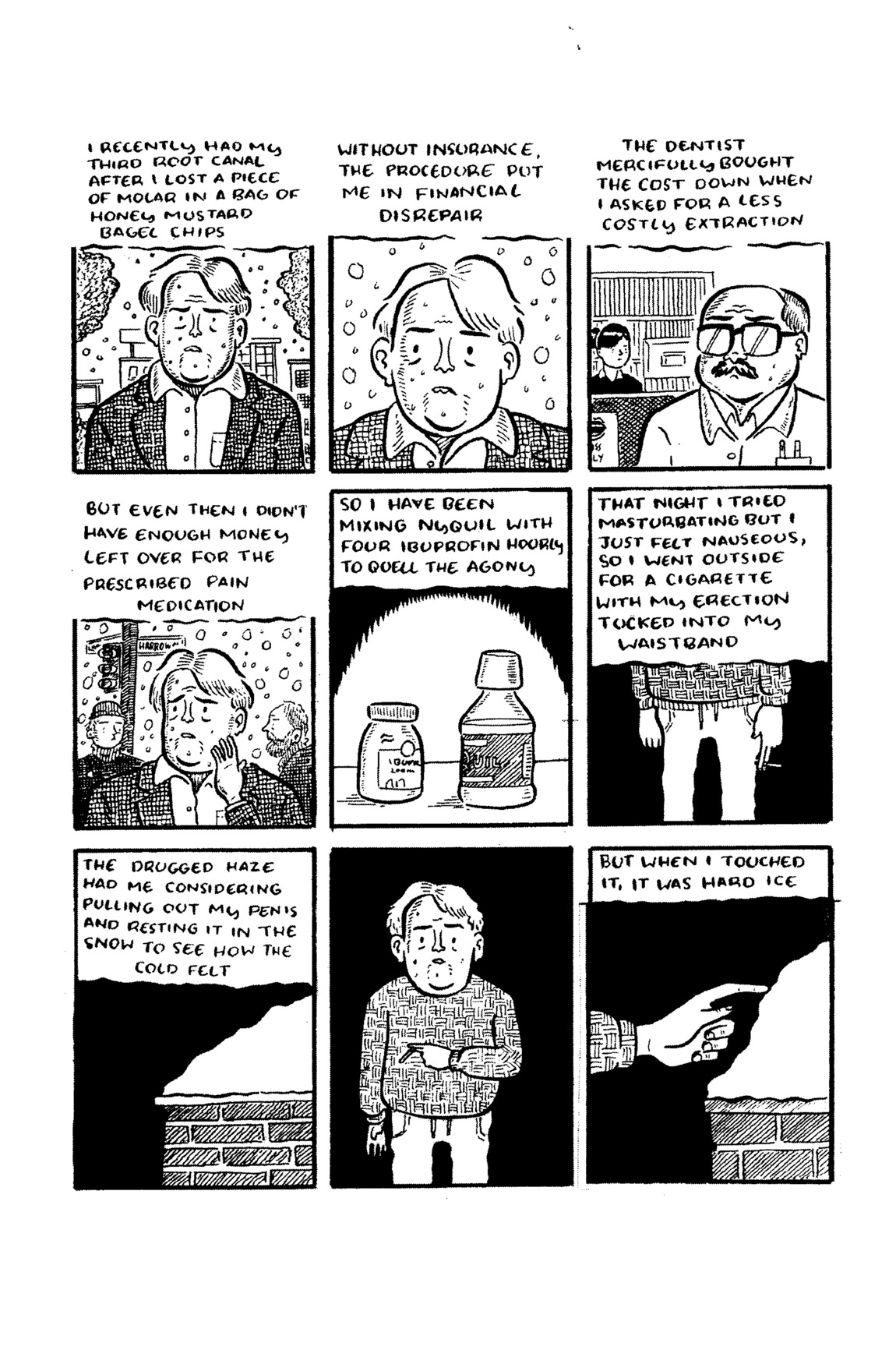

From Pleasure Beach.

From Pleasure Beach.Pleasure Beach and fiction vs. autobiography

How do you feel about being British in America at the moment? Do people make assumptions about you and your “Britishness”? And do you think of yourself as British or English?

I’m 100% American!

[Laughs.] Of course. That’s the right answer!

No, this is really weird to say, but after being here so long, I feel American, you know? Obviously there’s an element of me being an observer, but that’s also just part of being an artist. I’m naturally just observing more than I’m participating.

So you don’t miss the UK all that much?

I get very nostalgic sometimes, but it’s nostalgia for things that don’t really exist anymore. Euro ‘96, Oasis, that sort of Tony Blair-era of the ‘90s. Also, when I came of age, that kind of indie thing was really big. The Libertines, Babyshambles, The Streets, The Cribs, that was all huge for me.

I love the stickers you did for the Werewolf Jones Annual (available with copies purchased at Gosh Comics in London), where he’s cosplaying as disgraced British celebrities like Morrissey and Jimmy Savile, both of whom would still have been considered fairly respectable back in the ‘90s.

[Laughs.] I was a bit worried about the Jimmy Savile one, but nobody seemed to get mad about it. Nobody seemed to get the joke. Or they got it and thought it was funny.

But the ‘90s in general is a historical era now. Long gone.

Yeah. I sometimes feel very wistful, like I’d love to go back and drink ten beers in a park. But you can never go home. I’m doing this new comic, Pleasure Beach, right now, and it’s about exactly that.

The first issue is literally about the fear and awkwardness of going home after making a new life somewhere else. And it’s even set on an island.

It’s probably the most autobiographical thing I’ve done. But it also came from this recurring nightmare that I’m in my childhood home, but I can’t figure out how to get back to my current life.

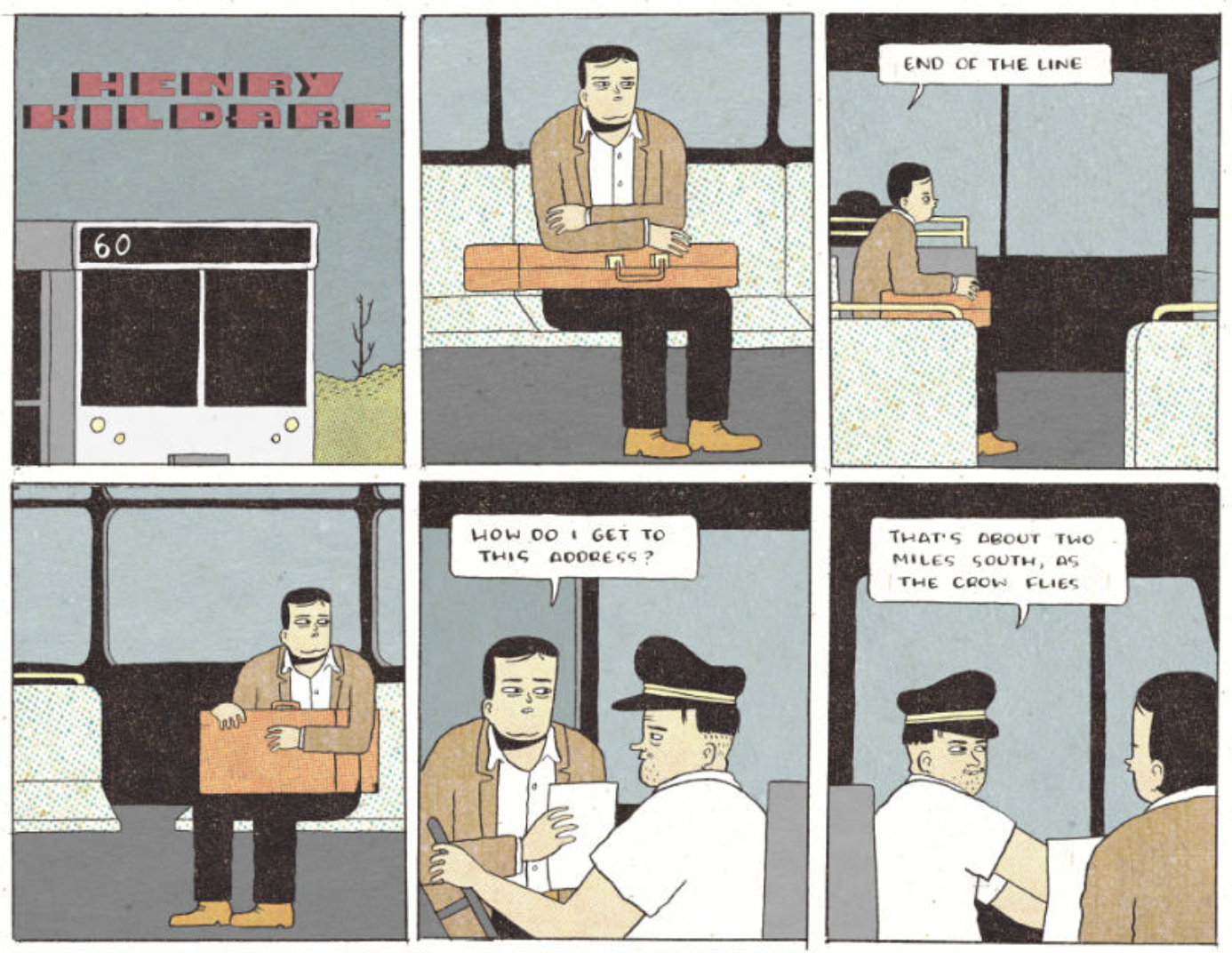

Henry Kildare from Goiter #6.

Henry Kildare from Goiter #6.That’s actually something I wanted to talk about. Despite their humor, there’s a real nightmarish quality to some of your work. Stories like Henry Kildare (from Goiter) or Fitting Room (from Tedward) start relatively normally, but the situations quickly go sour and just keep getting worse and worse. Have you ever suffered from anxiety dreams?

Yeah, I was in therapy for a little bit and told I have PTSD. Anxiety dreams or nightmares are an everyday occurrence. Sometimes I feel like I’m writing a straightforward story which feels relatively normal, like “here’s a fun little fiction for you!” And then later I realize that I’ve poured all these horrible anxieties into a character and recreated my nightmare scenario for them to deal with.

And part of that character has got to be you, of course.

It’s always a very thinly disguised “me”. I don’t think I’ve ever even drawn so much as a background character that isn’t me. Everybody’s a stand-in. I was recently reading Alex Graham’s The Devil’s Grin, and she writes these really well-thought-out ensemble casts, where every character is so deeply real, and that’s a skill I just don’t have. Which is why every comic I do is about one main character dealing with a scenario outside their control.

Having said that, Pleasure Beach feels like it’s shaping up to be your longest and most ambitious story so far. It certainly has a broader cast.

I think this is me trying to open up in that way, trying to take the writing more seriously. When you’re younger, you’re like an exposed nerve and just want to pour raw emotion into your art. But as I’m getting older, into my 30s now, I want to have more well-thought-out stories and characters.

What’s your approach when you’re working on a longer story like this one? Have you plotted the whole thing in advance?

Sort of. I know what happens from A to Z, but I try to leave enough space so there can be some improvisation during the writing phase, and even during the drawing. I know the story, but I’m also writing the story as I pencil it. I usually pencil a whole issue at a time and then ink it in one go. I don’t pencil and ink one page at a time. I like to let the writing happen on the page, so writing and drawing become one thing.

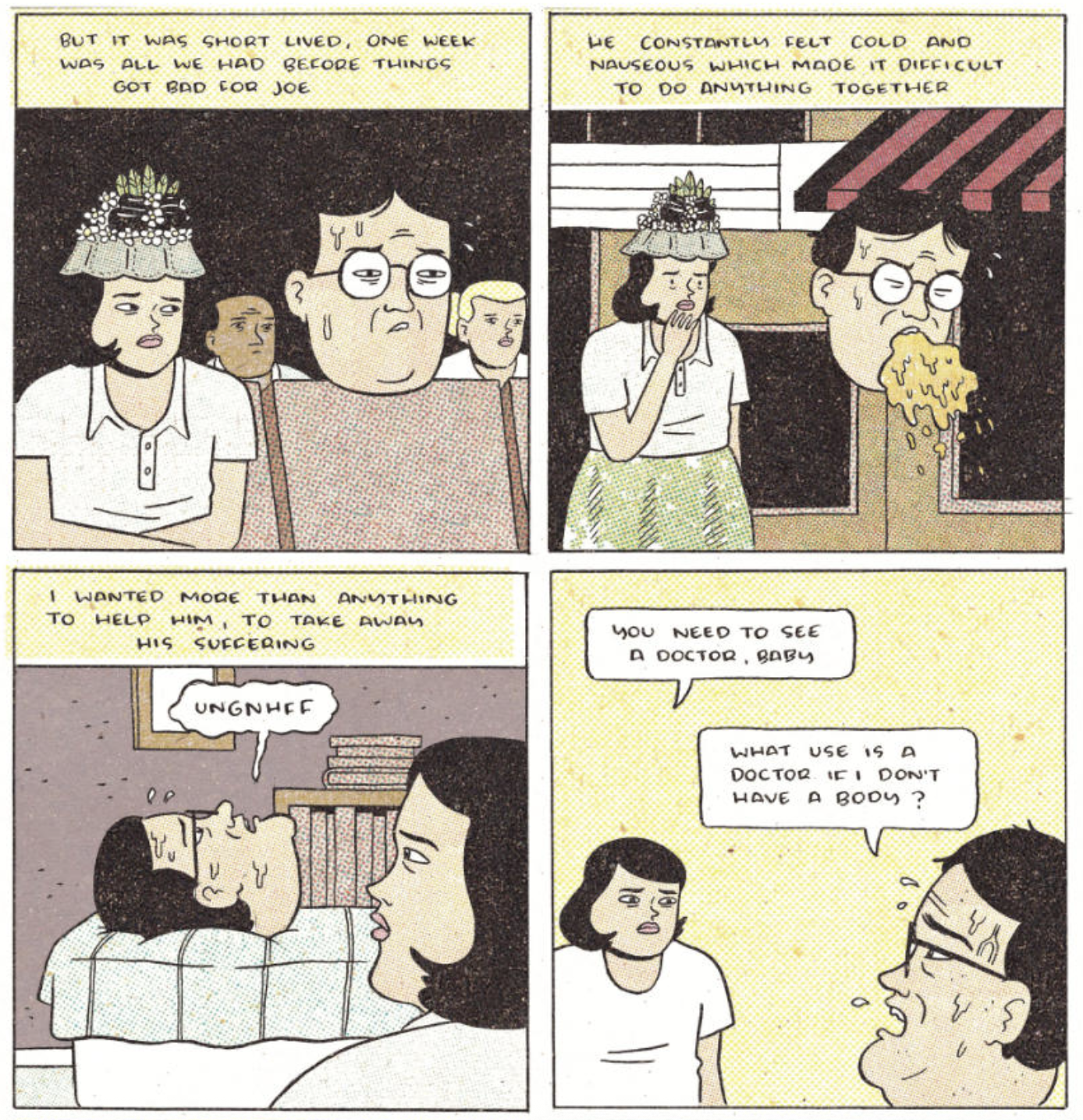

Page from Pleasure Beach.

Page from Pleasure Beach.It’s quite a leisurely beginning. The first issue sets up a number of plot strands, some quite straightforward, some utterly bizarre, but there’s no idea where it might go yet. What are your intentions for the story as it progresses?

It’s definitely my most personal story so far. I’ve created a sense of distance by making the main character a successful catalog model, so it’s not “me” exactly. But the story is going to explore a lot of weird and scary feelings that I have about my hometown, my family, and relationships with people I grew up with. But of course it’s heavily fictionalized. Sometimes, when you do that, I think you get to a deeper truth than just saying straight out, “here’s what happened." I think, unless you’re very careful, you can just end up telling a lot of lies that way.

Arguably, all autobiography is part fiction, even when it’s written in a relatively straightforward manner. It’s almost inevitable.

Exactly. Nobody ever perceives themself the way they really are. I get the feeling that a lot of autobio tends to lie about the important things, whereas if you fictionalize something, you actually end up lying about the unimportant parts of the story and can present, completely truthfully, the stuff that really matters; the more complicated parts of human relationships. And that’s not to denigrate anyone doing autobiography — there’s a lot of amazing autobio out there.

Are there any that you especially like? You mentioned Chester Brown earlier, for instance.

Yeah, there’s that. And I really like Julie Doucet, and Gabrielle Bell. One of my favorite comics of all time is Noah Van Sciver’s White River Junction (from Blammo #9), the one about the Center for Cartoon Studies. It’s so mean and funny, I love it. But in general I’m much more attracted to fiction. Comics are in a weird place right now, where concise, compelling stories are not necessarily the most celebrated thing. But it is the thing that will last. The pendulum will swing back and forth in terms of what’s fashionable, but compelling fiction will always be the thing that lasts. Although that’s just my opinion!

Do you have any idea how long the book will be when it’s finished?

I think about 250 pages, but I like the idea that it could be much longer.

Even 250 would make it your longest work by far.

Tedward was about 160 pages, and Goiter was just a collection of short stories, between four and thirty pages each. This is the first series I’ve done that isn’t just self-contained stories. With Tedward, there’s a narrative that runs through the whole thing, but it was originally designed to be individual zines, with a single story in each.

I always felt like Tedward could have gone on for a while longer. There could have been a lot more individual episodes.

I’d like to have done that, but I had these other characters and stories that started nagging at me, so I just let it end. But yeah, I agree, that’s a character that could have gone on. Maybe one day I’ll do another book with him.

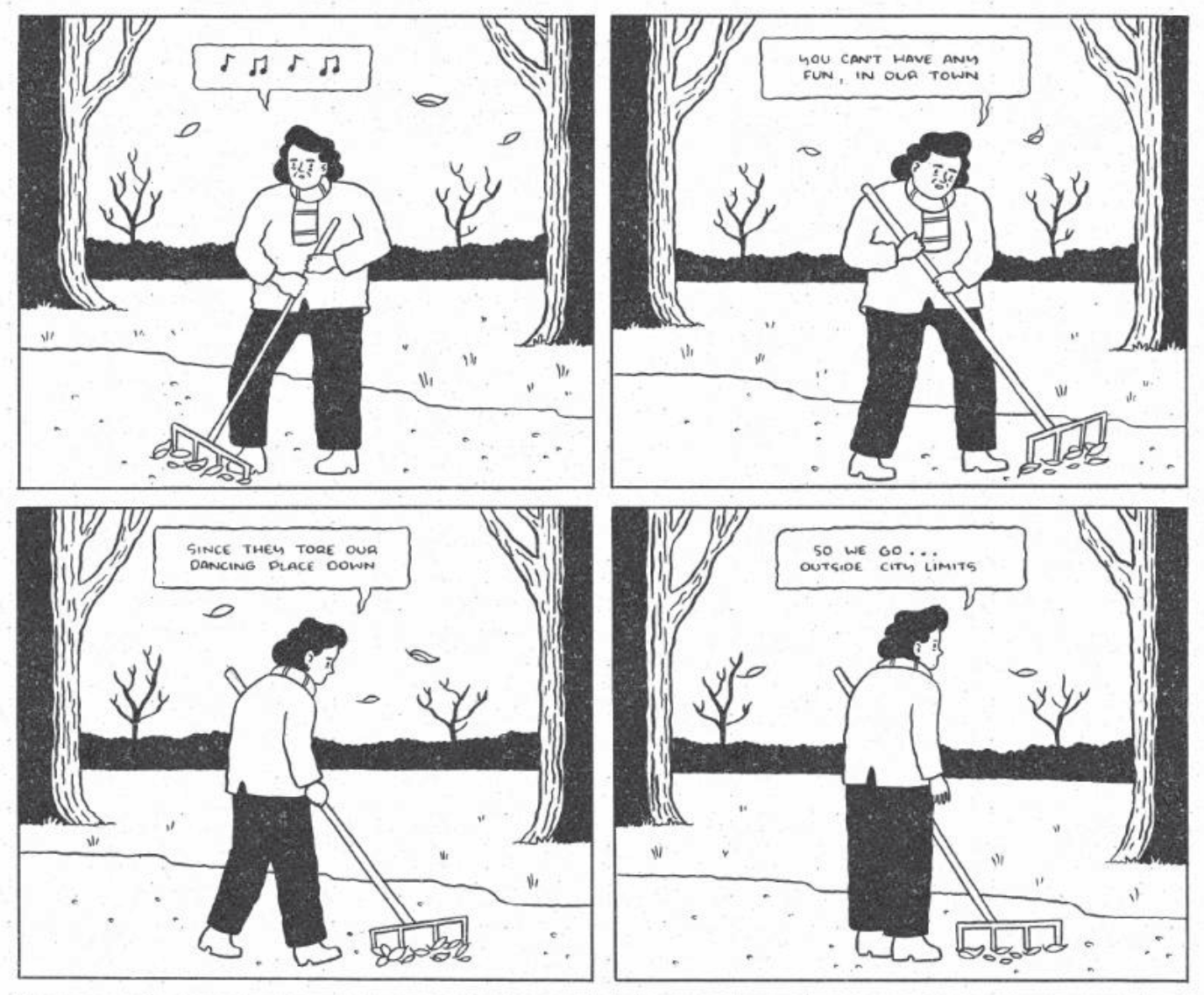

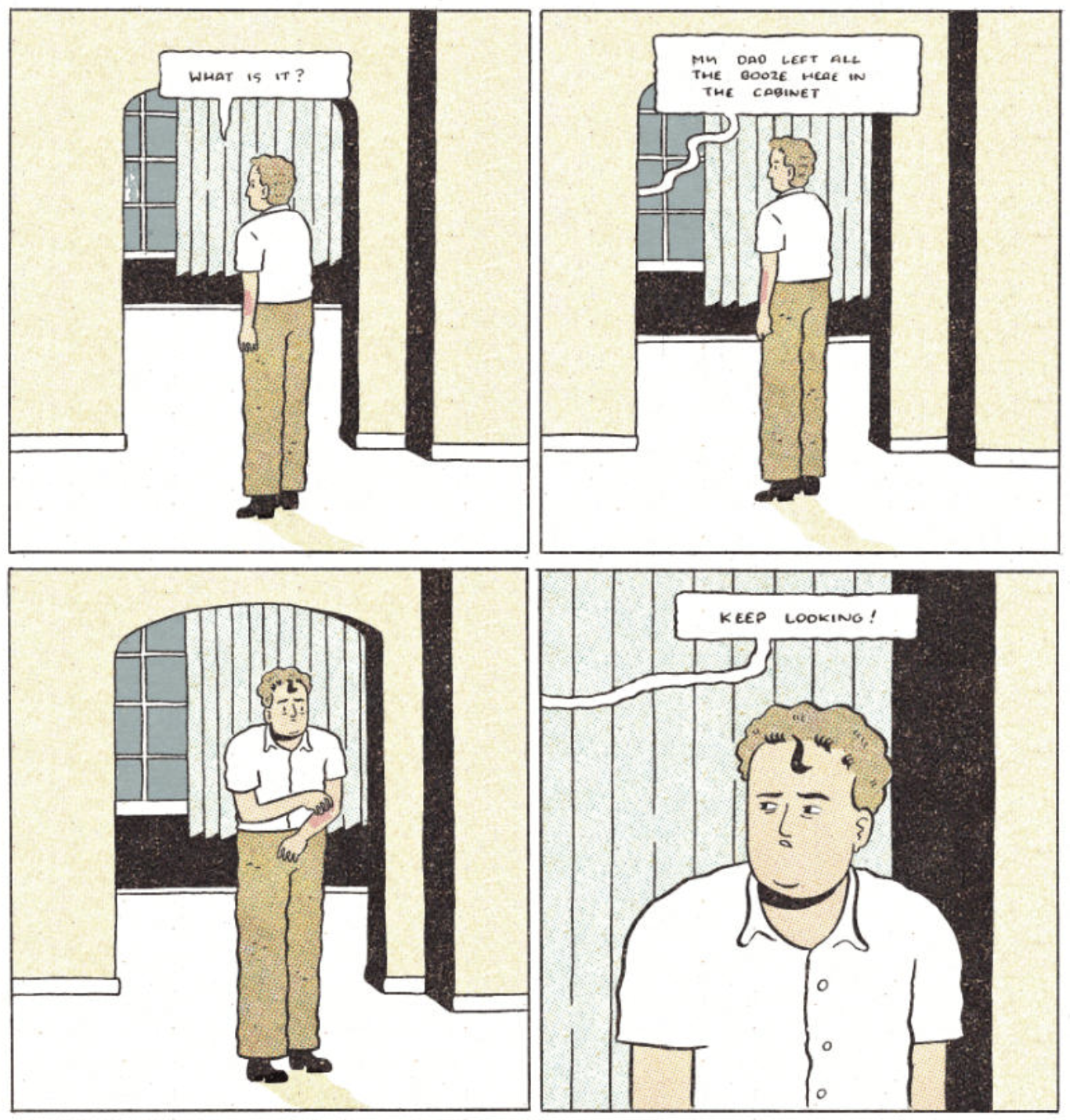

Sequence from the first issue of Goiter.

Sequence from the first issue of Goiter.Goiter

Skipping back a bit, your first experiment with comics was Goiter. The first issue was released in 2014, but the second didn’t appear until 2017. That’s quite a gap. What was happening between the two?

Goiter #1 was just 18 one-page stories, and then I basically had three years of false starts, trying to get the second issue going. But I just didn’t have the skills and didn’t know how to tell a longer story, so I was unhappy with everything I was doing. I was constantly making comics for three years, I was drawing the whole time, but there was nothing I wanted to put out. I was a little disappointed because I think I printed 30 copies of #1, but only one person wanted it (laughs). A nice little thing, though, is that the same guy still buys everything I put out. My most reliable reader! But the other 29 copies, I couldn’t give them away. So I thought I actually had to make something good, you know?

How were you promoting that first issue? How were you trying to get it out there?

Just Tumblr. Just failing at Tumblr, basically.

You were in Chicago at the time, which has quite a decent comics scene. Were you not a part of that?

No, I wouldn’t say so. My friend Alex Nall had a Drink & Draw, which we tried to get going for a long time. But most of the time it would end up with me and him, sad in a bar, just the two of us. I definitely felt like there was some kind of scene there, but I didn’t know how to integrate myself into it. A lot of it was connected to Columbia and the Ivan Brunetti comics course. A lot of people knew each other from there, and that felt like kind of a closed group.

So you were just doing your own thing?

Pretty much. Friday night, me and Alex, just drawing comics in a bar. Cool guys!

[Laughs.] If only people knew how cool that really was!

I know, right? And actually, coming towards the end of my time in Chicago, there was a place called The Chicago Publishers’ Resource Center, run by a guy called Johnny Misfit, and that was really cool. When they started hosting the Drink & Draw there, people started coming. But that kind of place isn’t financially sustainable, so it closed down. But it was a good place, with readings, events, and so on.

Sequence from Goiter #2.

Sequence from Goiter #2.But that three-year gap paid off, because your style had definitely matured by the second issue.

I think I was so frustrated with my inability to finish a comic and tell a story the way I wanted to, that it was simply a case of saying, “Alright, this is good enough!” In fact, I think pretty much all of Goiter is like that. I don’t love any of the work in the book, but it’s better to put out something rather than nothing.

Are you very self-critical in general? It seems like you tend to dismiss your earlier work as a matter of course.

Yeah, and my later work! [Laughs.] I think hating your own stuff is the only way to get better. If I thought that my comics were any good, I don’t think I’d work as hard as I do to try and get better at drawing and storytelling.

Sure, that makes perfect sense. In terms of improving your craft, do you draw every day?

Every day. The only thing that keeps me productive is momentum and routine. I wake up every day about 6:30, have my coffee, then I’ll go for a walk in the park, look at the ducks, and think about the story for the day. I usually start work at about 7:30 or 8 and work through to 5 o’clock. But it’s not constant, I’ll take a bunch of walks in between. Thinking walks, basically. That’s if I’m drawing. If I’m writing, it’s constant walks, every two hours. The stories only come together when I’m doing something else, like in the shower or walking. I have to be in the middle of a task.

Do you keep a sketchbook?

Not really. I’d be a better artist if I was a sketchbook person. But most of my drawing happens when I’m making comics. I get too perfectionist about it. Even if it’s just a sketchbook, I’m like, “this is a shit drawing,” and rip the page out. I’d just end up with a whole sketchbook of ripped-out pages.

[Laughs.]

I look at Tedward now, especially the earlier half of it, and I’m really horrified that it’s out there. Actually, I shouldn’t say that, because I want people to buy it! But this is just the way I view my own work. I didn’t feel that way when I was drawing it — I thought it was the best stuff I’d done so far. Right now, I’m very happy with the way Pleasure Beach looks, and I’m happy with the story, but I think I’ll come to hate it. That’s how the next thing will be better, you know?

Sequence from Goiter #3.

Sequence from Goiter #3.Are you ever tempted to redraw anything for the collected editions?

I know some people do that, and the books would be better for it, but I feel like I’d lose momentum on my current projects if I did the same. I like to release everything in black & white zines first and then have the book version in color, so I’ll do little fixes when I’m coloring. But a lot of that is just moving facial features around and little things like that, rather than redrawing anything.

So that’s done digitally?

Yeah, like a little Photoshop fix.

Quite a few of the original issues of Goiter were in color, though, not black & white. And the color has a really interesting, textural quality to it.

Yeah, it’s all taken from old comics and added to mine digitally. With those, I’d find an area of background color in an old comic book that was large enough, scan it into Photoshop, and then paste it in under the linework. But I look back on it now and realize that it was just a sort of crutch because I was unhappy with the drawing. When you do flat color, you fully see the drawing, so I was trying to do something interesting …

… to disguise the faults?

Exactly. But now I look back and don’t think it worked.

Still, it gives the whole series quite a nostalgic, retro feel. In fact, there’s something slightly “old-fashioned” about a lot of your work. It seems to exist somewhat out of time. Some of it could almost take place anywhere from the ‘50s to the ‘90s. There are no cellphones, the TVs are these enormous, blocky contraptions …

That’s all very much by design. I don’t want to set my comics in any specific time in the past because then you’re stuck with trying to recreate things accurately, and you have to depict certain attitudes of the time. But I also don’t want them to feel like they’re set in 2025 because, story-wise, it offers too many easy solutions. If you have a character who’s trying to figure something out, is it more interesting for them to Google it on a phone or go to the library? There are too many easy solutions that aren’t interesting to draw or read about. Pleasure Beach is probably set “now”, but I still haven’t included cellphones in it. The main character, Beryl, uses a paper schedule to catch the ferry, and once she gets to the island, she’s trying to get hold of her mum on a pay phone. I still like that sense of trying to find someone being difficult. I need that feeling to exist in a story.

The fashion in Goiter, and throughout your work in general, is also pretty unique. Especially the crazy hats. Are they inspired by anything in particular, or just products of your fevered imagination?

[Laughs.] No, the fancy hats are all from an old Sears & Roebuck catalog. All those hats are drawn directly from that.

It must be quite liberating to simply ignore a lot of 21st-century culture and technology, or pretend it never even existed. Would it be safe to say you’re not a fan of the internet in general?

Well, I need it for my career, and there are good things about it. I recently paid for the Criterion Channel and love having access to all those great movies. But if it was up to me and I could choose to have it obliterated tomorrow, would I turn it off? Probably. Although I’d also miss lots of it.

It’s an amazing tool, but has a habit of dominating our lives. And that’s one of the major themes of Victory Squad (serialized in Goiter #6-8), which is a sort of mash-up of dystopian classics like 1984 and Brave New World. Were they influences, or did it just develop out of a deep-rooted hatred of Amazon?

What happened there was, right at the beginning of the pandemic I was walking around my neighborhood in Chicago and I noticed that every single house on my street had multiple Amazon packages outside every morning, and I developed this real sense of paranoia that we were about to go through this massive shift, where Amazon was going to replace everything, and the story just developed from that; a sense that we were about to give one company a complete monopoly over everything in our lives.

It may still happen.

Quite likely. But the downfall of that story was that it didn’t, and so I lost some of the fear and anger that I was feeling at the time, and stopped caring that much about it.

It does feel like it finished a bit abruptly. There could have easily been another chapter or two.

I think so, but I just wanted out of it.

And you wanted to finish Goiter (the series) too?

Yeah, I’d gotten to issue eight, and the idea of a continuing series started to feel less exciting. I wanted to start making work that felt like an event each time something came out.

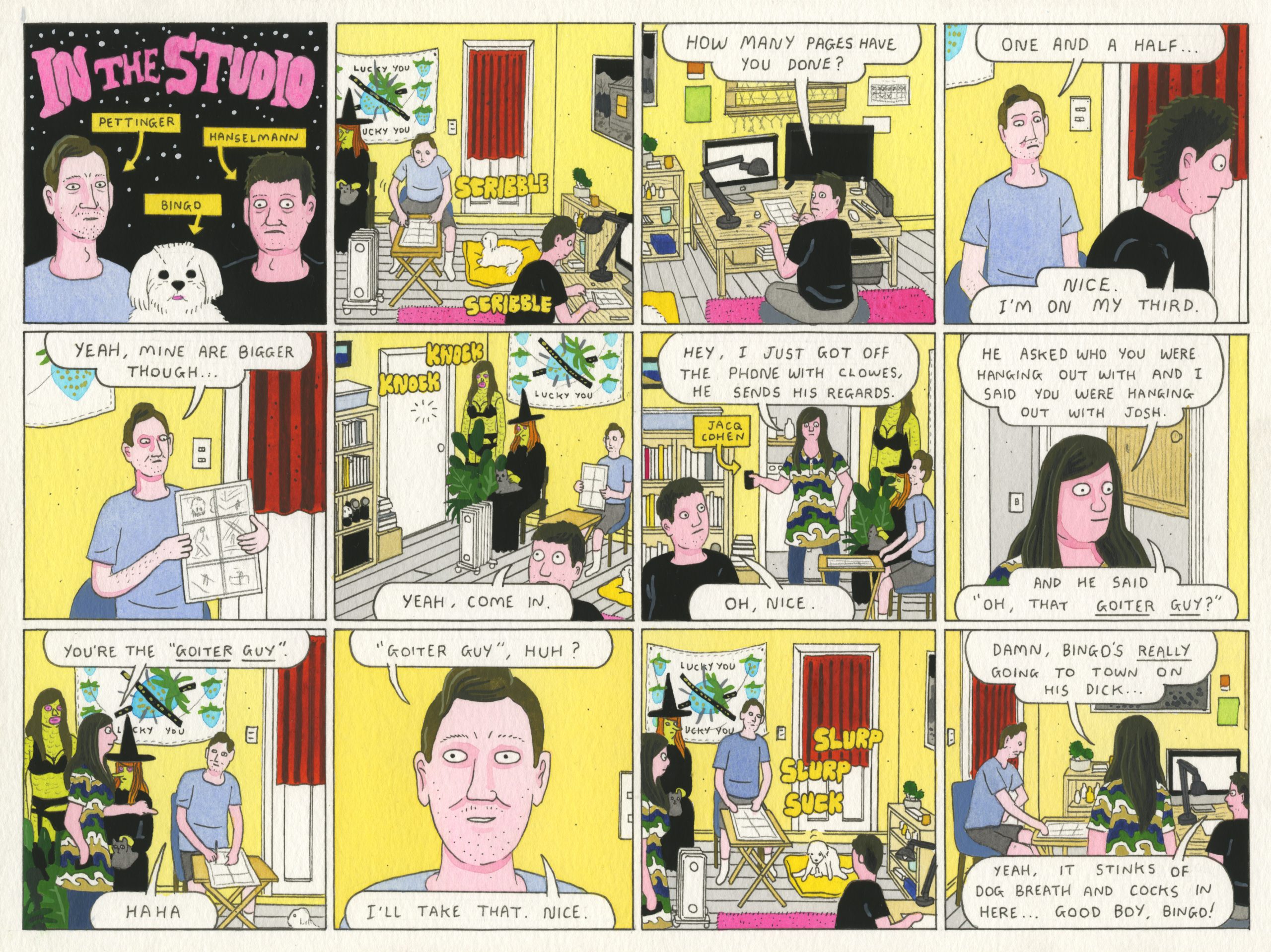

"In the Studio" by Simon Hanselmann

"In the Studio" by Simon HanselmannDid Dan Clowes really refer to you as “That Goiter guy”? (as recounted by Simon Hanselmann in the story In The Studio)

I wasn’t privy to the actual phone call, but that story Simon drew in the back of the Goiter collection did happen.

At least it proves that you had some brand recognition.

Although I actually hated the name of that comic pretty quickly.

It’s an odd one, certainly. It’s up there with The Fart Party (by Julia Wertz) when it comes to regrettable comics names.

At first, it seemed like an interesting name. It jumps out at you. But I’m not good at body horror stuff …

… So if you’re searching for “Goiter” on Google …

Yeah, it definitely makes it harder to Google myself. But there’s also that paranoia that I’ve said “Goiter” too many times in my head, I’ve thought about “Goiter” too many times … I’m going to end up giving myself one, you know? When I was first talking with my friend Jacq Cohen (then executive director of marketing, communications, and publicity at Fantagraphics) about a Tedward book, she was like, “I don’t want to work on a book called Goiter!” And that was understandable, I didn’t want to either.

In the end, the first collection of Goiter came out in France (from Ici Mȇme Éditions). All of a sudden you were like Charles Burns, having your books published in a foreign language before they’d even appeared in English.

Ici Mȇme was the first publisher to really believe in my work that way. They’ve been great. They somehow managed to get some proper mainstream press for it, it was nominated at Angoulȇme and did really well in France. It sold out its original run and is now in its second printing. I’m getting royalty checks. So that’s nice.

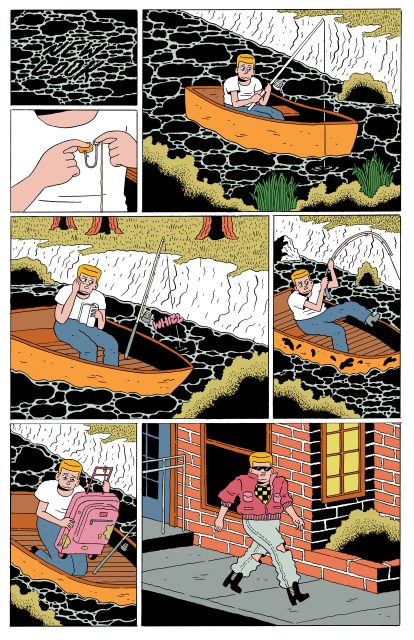

From Tedward.

From Tedward.I live in a small town in rural France, and even my local bookshop has copies.

Really? Make sure you print that. I definitely want people to know you can find me in rural France!

[Laughs.] Absolutely! That’s a real sign you’ve made it.

France has really embraced the sensibility of my work. If I didn’t live here, I have fantasies of living in a village in France and just working on comics there.

Well, you just moved from Philadelphia to San Francisco, and that’s pretty much the same trajectory that Crumb took back in the ‘60s. Maybe you’ll end up following his lead and eventually relocating to France as well.

[Laughs.] I didn’t think of that! But to distinguish myself, I’d move to the north of France. If my morning walk could involve a trip to the baker’s to buy a baguette or whatever, I’d love that, but otherwise I’ll stick it out here. Last year I got sent over there twice, both times all expenses paid. One of the festivals was in Colomiers, where Airbus is based. They basically fund the festival, and they’ll fly guests in and feed 300 people in these massive banquet halls. Angoulȇme felt very special too. The whole town is just about comics. This is not new, everybody says this, but the way they treat the arts is incredible. I got profiled in Libération and Le Monde, and then Italian and Spanish newspapers too. My work is by no means mainstream over there, but these weird indie comics can get mainstream press.

How many languages have you been translated into now?

French, Spanish, and Italian. The Werewolf Jones stuff I did with Simon has also been translated into Swedish and Polish.

There’s a huge difference between the French edition of Goiter, which is an enormous hardback printed on heavy paper, and the version published in the U.S. by Floating World, which is a slim paperback on newsprint. What was the reasoning behind that?

I’ve gotten some criticism about the Floating World edition, but they did exactly what I asked for. I said, “6 x 9, and can you do it on newsprint?” And, to their credit, they printed it the way I asked them to, although it’s quite difficult to read some of it! But I love Floating World.

Sure, they do some great books. And, despite the small size, it’s actually a very satisfying object in itself. It feels lovely in the hand, flicking through it, and the newsprint effect really works. But yeah, speaking as someone who’s quite shortsighted, there are certain stories where I had to use a magnifying glass.

I’ve heard that a lot. They did a great job printing it, but it’s definitely very tiny lettering. I can barely read some of it! But they did what I asked them to do, so I can only really blame myself. And there’s also this thing where I’m kind of embarrassed about this early work. So I see the French edition, and it’s printed big, and it’s beautiful, but I open it up and I can really see the flaws in it. So there was an element of trying to hide the mistakes.

[Laughs.] I see. That’s very cunning.

I also wanted it to feel a bit disposable. It really folds, and if you have the right coat, you can slip it into a pocket. It’s like a read-on-the-bus kind of a book. I don’t want this work to survive the apocalypse, you know? It’s like, as I improve, it’s OK if this early work just degrades and falls to pieces and ceases to exist.

Sequence from Goiter #5.

Sequence from Goiter #5.Self-publishing

The original issues of Goiter are actually more substantial than the collection. Most of them were self-published, except for #5 and #6, where you went with Tinto Press and Kilgore Books. How did that come about?

I think I just wanted the sense of legitimacy. At the time, Blammo (by Noah Van Sciver) was being published by Kilgore, and Tinto had done some nice books too. I really loved stuff like Joseph Remnant, and there seemed to be a movement at the time with some publishers towards floppies, which gave them a kind of legitimacy.

Kilgore was doing great stuff at the time, by people like Inès Estrada, Robert Sergel, Alex Graham

Yeah, it seemed like a valid goal at the time, but you make much more money self-publishing. Financially, it doesn’t make sense to go with a publisher for floppies. I think I made maybe 300 or 500 dollars for each of those, and that’s all the money you’re going to see. Whereas, if you can sell like 1,000 copies self-publishing, you can make a lot more.

It’s the difference between paying the rent for a while and just buying a few groceries. It’s not like the ‘90s, when Eightball or Hate were selling in the thousands.

Exactly, yeah. It was nice at that point in my career to be published. It felt good, but it’s not a sustainable thing to have floppies published by somebody else.

So, by self-publishing the individual zines and having a publisher for the collections, you get the best of both worlds.

Yeah, and I’ve recently had a really great experience with the Tedward book being published by Fantagraphics. I love them, and I love the way they did the book. But I’ve kind of reframed it for myself now that the big, fancy, embossed hardcover books are like an advertisement for the self-published stuff, which is how I've managed to be a full-time cartoonist for the last five years.

How many copies of each issue are you printing these days?

It varies. Usually, I can sell around 1,000 of a zine. Pleasure Beach was a little less, but there’ll be a second printing, which will bring it up to over 1,000.

And you’re averaging, what, three or four per year?

Usually three main zines, so four months per zine.

Have you been hit by increased shipping costs, especially internationally?

Yeah, that’s been a nightmare. That’s basically why I printed fewer copies of Pleasure Beach. Since the French book came out, I’d been getting a really decent number of sales to France, and a decent amount to England, Spain, and Italy. But that’s dropped down to, like, single figures for each country because it’s $25 shipping for a $13 zine. That’s crazy!

And then they hit you with customs charges when it arrives!

Exactly. I’m quite lucky that some stores like Gosh (in London) and Mansion Press (in France) will buy a large amount from me, maybe 30 or 40 copies. It’s a fraction of what I used to sell to Europe, but I can still get some books out there. My sales in the US stay the same, or are slightly more with each new zine I put out, so there’s growth there, but since the post office has fucked their prices, everyone I know is getting completely screwed by the situation. We’re going to have to find a way around it somehow. I’ve tried selling PDFs, but that’s such an impersonal thing compared to getting the physical object directly from me. It’s kind of scary. I don’t know what’s going to happen, and what it’s going to do to comics.

Collaboration and Manga Chat

Let’s move on to your collaboration and friendship with Simon Hanselmann. Was he already in L.A. when you moved there?

No, I moved there a little bit before him. We became friends online. I think he’d read the interview with me in Bubbles fanzine and saw that we had some common interests. I think I mentioned Jam, and Chris Morris, and Alan Partridge, and that kind of thing, so we started talking online. And then he had a baby and moved to L.A. a little later in the pandemic to be closer to his wife Jacq’s family. Once he moved there, we started hanging out. I’d go to his house and draw for whole days, and the collaborations just grew from that.

You have similar sensibilities in many ways, and seem to slip into each other’s characters quite easily.

He’s always been someone who wants to collaborate. He’s done all those zines with HTML Flowers and other stuff. I’m less inclined to collaborate with people, but it appealed to me because I think he’s the funniest person in comics. One of the best comedy writers in any medium in fact. So of course I’d want to collaborate with him. He’s like my best friend.

And that led to Manga Chat, which is a great way to promote both yourselves and up-and-coming cartoonists.

Exactly. Simon is someone who’s very invested in his friends and wants them to have success. This is a medium where most people are pulling the ladder up after themselves, but he’s the opposite of that. He wanted to do Manga Chat to constantly be promoting other people’s work. He has a big platform, obviously, and he wanted to use it to promote the stuff he likes, and his friends, and create a kind of community. A lot of our friends live in different parts of the country, or all over the world, so he wanted to promote our side of comics, which doesn’t get written about as much.

Why do you think that is?

Maybe it’s harder to write about funny comics, or people aren’t as interested in doing it. But people read them, and people like them. Well-written comedy is like a magic trick, you know? In my opinion, it’s much harder to do than good drama. But maybe it’s harder to write about, and enthuse about, so it doesn’t usually get promoted in the same way. If you’re promoting a book about a meaningful life story or personal tragedy, it’s pretty straightforward to describe and promote. But if you have a really funny book that’s disguising personal tragedy with comedy then it can be more complicated to sell.

Although, once you get under the surface of your work, or Simon’s, you realise that there is a lot of emotional depth to it. It comes from a very personal place.

We know that, and the readers know that, so our thing with Manga Chat is to get this stuff talked about. To give it some visibility in “the scene” or whatever you want to call it. We have mixed results, of course. I mean, I’ll be the first to admit that I’m not a natural broadcaster. But we have a loyal audience that we love, so it’s fun to do. And we’ve started putting a little more “production value” into it recently. I’ve gotten really into birding since I moved to San Francisco, so we have a little birding section in there now. Then there’s Simon’s “DVD Corner” and a section about his gardening. We’re trying to make it a little more concise and structured.

Tedward

I’d like to end by talking about Tedward. Of all the characters you’ve created, he seems like the one who fits most easily into a very British kind of “comedy of social awkwardness.” He’s like a distant relative of Mark Corrigan (Peep Show), Howard Moon (The Mighty Boosh), and Alan Partridge; desperate to be liked, but without enough self-awareness to know how to behave around others. You’ve already said that there’s an element of autobiography in your work, but do you feel that way about yourself?

There’s a lot of autobio in Tedward. First, there’s the fish out of water element, which I think is like me being an English person living in America. And I think he represents a lot of the more repressed aspects of my personality. But he also does just come from that lineage of, like you say, Mark Corrigan, Alan Partridge, and a little bit of Pee Wee Herman as well. The way I’ve been describing this book to people is, “If Pee Wee Herman was in the movie Falling Down.”

The endpapers from the Tedward collection.

The endpapers from the Tedward collection.There’s a repeated image you use (on the endpapers and elsewhere) of Tedward being haunted by a massive version of his own head. It’s almost like he wants to escape himself, but can’t.

That’s exactly it. He’s the biggest victim of Tedward. That’s the vibe I was going for with that element of the book design. Obviously, I made this book to be funny first, but there are a lot of autobio elements in it, like in the story Warm Television. I don’t know if you ever experienced this, because I speak to Americans and they’re completely baffled by it, but we were so poor growing up that we couldn’t afford a television. And one option was this company that would give you a television for free, and it was coin-operated, so you could put a pound in and watch television for, like, an hour or something. We had that for a lot of my childhood.

I’d never heard of that. I honestly thought it was made up!

[Laughs.] No! I think I’ve only ever met one other person who’s heard of it. But I remember telling someone about it in casual conversation, and them being so baffled by it. That’s when I realized, “Oh yeah, there’s definitely a story there!” And then, Power Wash is a kind of metaphor for the service industry. I worked in restaurants for years, and they were mostly fine, but when you work in one of the higher-end ones it can feel a bit like you get treated the way Tedward does while he’s washing cum off rich orgy-goers. It’s using really absurd, heightened scenarios to try and get at something real.

From Tedward.

From Tedward.They’re incredibly funny stories, but they combine humor with these much darker, sometimes almost dream-like elements, which makes them quite unsettling and gives them a real depth.

I hope so, yeah. In a lot of reviews of my work, the word “strange” gets mentioned, but I really do feel sometimes that I’m telling a straight story, and that’s just the way it comes out. I don’t feel like I have a lot of control over my creativity. I don’t just sit down and say, “Oh, I’ve got to have an idea.” It comes through me from somewhere else, you know, and I don’t have control of what comes out. I mean, I do, obviously, but it’s limited.

There’s a moment in the story Tracy Island where Tedward says, “I have this idea that being recognized for doing something well is the same thing as being understood. I’m not asking for the whole world to see some special quality in me, just one or two people that appreciate me trying my best.” That almost sounded like it could be you addressing the audience directly.

Yeah, I think that’s me directly talking, maybe not in the healthiest way, about the kind of fulfillment you try and get from communicating something of yourself, putting it out in the world, and hoping that it speaks to other people. This weird experience of life you’re going through, you’re not alone in that. Especially now, when I think so many people are feeling untethered and afraid. Even on a personal level, relationships with other people, not specifically people you know, but everyone around you, it all feels a bit untethered and unhinged, like there’s a kind of disconnect. I don’t know …

It reminds me of another quote from Goiter: “Have you ever felt like life was happening around you, but not to you?”

That’s something I felt a lot, especially in my twenties. That was the feeling I was trying to get at in a lot of my work, the sense that things were moving too fast, so it was hard to grip onto something and have some control. I don’t feel that way so much now, but that was a constant feeling back then.

Did the therapy help with that?

It definitely helped. Therapy was great for a while. I’m not as anxious as I used to be, or, if I am, I can identify that feeling and use it with more intention in my work, rather than just grasping at thin air. Growing up, I was surrounded by a lot of aggression. But thanks to therapy, I’m really normal now. [Laughs.]

So does this mean the comics will suddenly become incredibly dull and boring?

Yeah, most likely I’ll start working on IPs.

[Laughs.] Sounds good. I look forward to seeing that next year.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·