Hank Kennedy | July 31, 2025

“Just like a mule

A goddamn fool

Will scab until he dies”

— Coal miner’s song, quoted in The Labor Wars: From the Molly Maguires to the Sit Downs by Sidney Lens

Political cartoonist Art Young’s response to the 1913 West Virginia coal miner’s strike almost landed in prison. The longtime socialist drew a cartoon showing the president of the Associated Press slipping a vial of poison into a pool labeled “the News.” If a similar cartoon ran today, the vial would be labeled “fake news.” The cartoon appeared in the Masses, alongside an editorial by Max Eastman accusing the AP with being “The Worst Monopoly.” The news service suppressed information about the strike. Their own representative in West Virginia (Cal Young) served on a military tribunal charged with trying strikers, a clear conflict of interest. Eastman argued the AP’s practices showed the truth was “for sale to organized capital in the United States.”

The accusations would be substantiated decades later in muckraker Upton Sinclair’s The Brass Check, but at the time the AP fought back by bringing cases of criminal libel against Young and Eastman. When it became clear that a trial would bring to light damaging information about the AP and its biased news coverage, they determined discretion was the better part of valor and dropped the case. With his characteristic humor, Young remarked, “the AP was in the position of the hunter who had a bear by the tail and didn’t know how to let go of it.”

The accusations would be substantiated decades later in muckraker Upton Sinclair’s The Brass Check, but at the time the AP fought back by bringing cases of criminal libel against Young and Eastman. When it became clear that a trial would bring to light damaging information about the AP and its biased news coverage, they determined discretion was the better part of valor and dropped the case. With his characteristic humor, Young remarked, “the AP was in the position of the hunter who had a bear by the tail and didn’t know how to let go of it.”

Black Coal & Red Bandannas: An Illustrated History of the West Virginia Mine Wars, written by Raymond Tyler and illustrated Summer McClinton and brought to us via a collaboration between PM Press and Working Class History, returns cartoons and comics to this volatile period. McClinton is an old hand at this type of material, as attested to by her drawings in Harvey Pekar’s Huntington West Virginia, “On the Fly”and Masks of Anarchy: The History of a Radical Poem, from Percy Shelley to the Triangle Factory Fire. The latter comic depicted another bloodbath in labor’s 20th century story, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire.

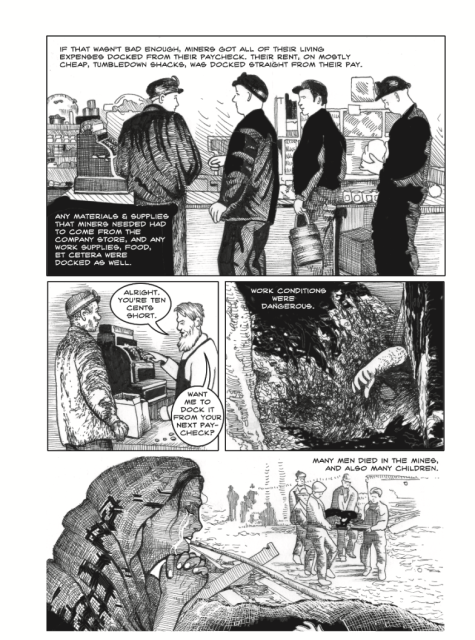

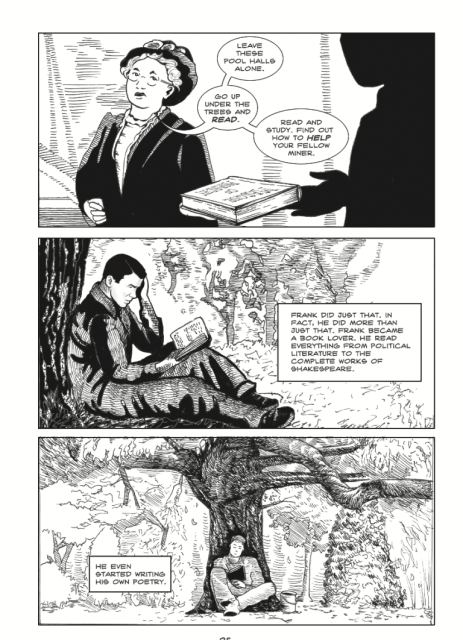

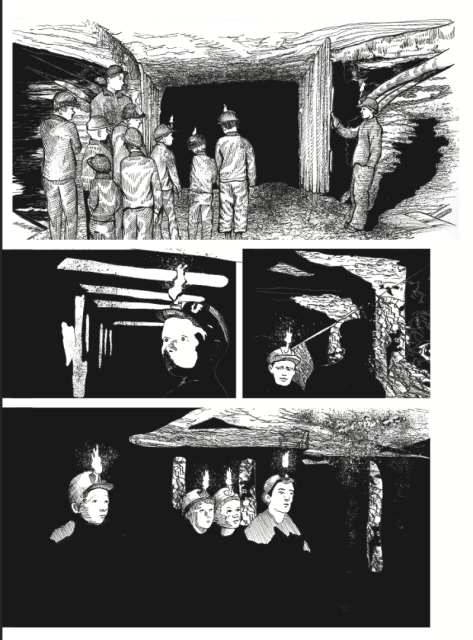

Like the girls and women of that factory, miners were exploited and abused. Children working in coal mines was a common sight. Workers lived in company towns owned by their boss. They could be removed at the bosses discretion if they were suspected of union sympathies. The costs of equipment and food were deducted straight from a miner’s paycheck. Health and safety legislation was nonexistent. A commission sent by the mayor of New York assessed the condition of coal miners as “worse than the serfs of Russia or the slaves before the Civil War.”

Like the girls and women of that factory, miners were exploited and abused. Children working in coal mines was a common sight. Workers lived in company towns owned by their boss. They could be removed at the bosses discretion if they were suspected of union sympathies. The costs of equipment and food were deducted straight from a miner’s paycheck. Health and safety legislation was nonexistent. A commission sent by the mayor of New York assessed the condition of coal miners as “worse than the serfs of Russia or the slaves before the Civil War.”

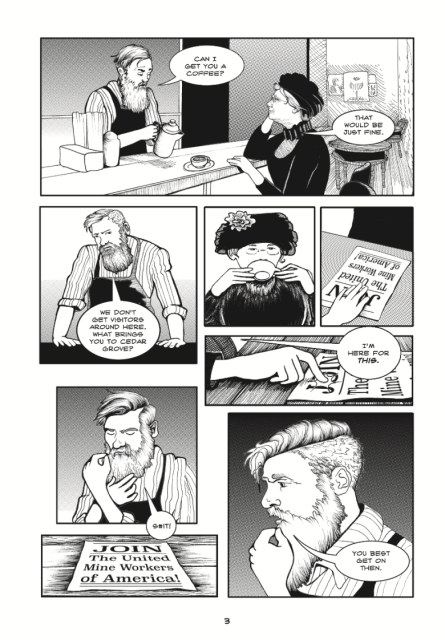

The comic begins with Mother Jones, alias Mary Harris Jones. Jones is a legendary figure in labor history. An Irish immigrant, she lost her husband and children to disease before dedicating her life to the cause of labor. She steps off the train and saunters into the saloon, like a gunfighter from an old western. Upon receiving directions to a miners’ camp, that image is undercut. She struggles to make the rocky hike, reminding readers that this is still a woman in her 70s. At one point she paraphrases Lethal Weapon, saying she’s “too old for this stuff.” Instances like this remind one that for all the larger-than-life figures met in Black Coal & Red Bandannas, they too are people.

Raymond Tyler’s writing manages to compress twenty years of history into roughly 100 pages of comics. He incorporates real-life quotes into his dialogue. When Mother Jones is jailed, tried and convicted by a military tribunal that Cal Young probably served on, her cellmate tells her he stole shoes. She replies, “If you’d stolen a railroad, you’d be a U.S, senator!” In other instances, the dialogue is cleaned up, to allow the book to be used in classrooms and union halls alike. It seems unlikely that coal company gunmen would yell out “Don’t fricking run!” or “Nobody fricking move!”

McClinton uses many filmic conventions in telling this story. Aside from the aforementioned train arrival, the Battle of Matewan is framed like a classic western. Westerns traditionally heralded the victory of capitalist development over nature and the natives. Reframing the battle between miners and coal company gunmen as a western flips this this narrative. Her beautiful landscapes capture the environment of West Virginia coal country, particularly in the double page spread that ends the comic.

As the title indicates, color is essential to the work. Black backgrounds emphasize despair and desperation. The fate of Mother Jones’s husband and children and the cave-in that nearly killed union organizer Frank Keeny are both accompanied by them. By contrast, red indicates action and resistance. Miner’s headlights, the Great Chicago Fire, sound effects, and certain lines of dialogue share the color of the titular bananas.

In her compositions, McClinton evokes the labor cartoonists that would have been familiar to early union miners. Coal bosses sit drinking while complaining, “People these days expect things handed to them. Not me and my brother, no, we made our way ourselves.” In the panel below, miners bent-double dig away. The boss cradles his wine class, arguing “We created our own wealth!” The next panel shows a miner covered with dirt. A chain is in the foreground, symbolizing his confinement to poverty and misery. McClinton subtly homages her predecessors by drawing characters reading the socialist newspapers Appeal to Reason and the Liberator (successor to Young’s Masses).

In her compositions, McClinton evokes the labor cartoonists that would have been familiar to early union miners. Coal bosses sit drinking while complaining, “People these days expect things handed to them. Not me and my brother, no, we made our way ourselves.” In the panel below, miners bent-double dig away. The boss cradles his wine class, arguing “We created our own wealth!” The next panel shows a miner covered with dirt. A chain is in the foreground, symbolizing his confinement to poverty and misery. McClinton subtly homages her predecessors by drawing characters reading the socialist newspapers Appeal to Reason and the Liberator (successor to Young’s Masses).

The United States has perhaps the bloodiest history of class conflict in the Global North. The Ludlow Massacre, the Calumet Disaster, the Everett Massacre, the lynching of Frank Little, the Memorial Day Massacre. These are but a few examples in addition to the material covered in this book. That citizens of this country are not taught much of this history is surely a reason why the rich always seem to be winning that conflict. Even helpful historians have let us down in this regard. Creative director of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum Shaun Silfer points out in his introduction that Howard Zinn left out the Mine Wars in his landmark A People’s History of the United States.

The United States has perhaps the bloodiest history of class conflict in the Global North. The Ludlow Massacre, the Calumet Disaster, the Everett Massacre, the lynching of Frank Little, the Memorial Day Massacre. These are but a few examples in addition to the material covered in this book. That citizens of this country are not taught much of this history is surely a reason why the rich always seem to be winning that conflict. Even helpful historians have let us down in this regard. Creative director of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum Shaun Silfer points out in his introduction that Howard Zinn left out the Mine Wars in his landmark A People’s History of the United States.

Black Coal & Red Bandannas brings to life a violent period in U.S. labor history, full of heroic deeds and dastardly betrayals. Tyler and McLinton leave pair the aforementioned mountain view with this text: “These mountains and these folks are beautiful...but if the capitalists could make a dollar off it, they’d level these hills and all the people in it.” That could augur a sequel about the fight against mountaintop removal mining, another battle in this country’s long-running economic war.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·