This Place Kills Me

This Place Kills Me

Writer: Mariko Tamaki

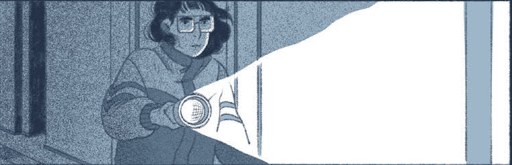

Artist: Nicole Goux

Publisher: Abrams

Publication Date: August 2025

One of the worst things in the world is having people talk about you behind your back. The reason for this is rather obvious: They think you can’t hear them. This is especially true in small communities like a town or a private school for teenage girls. Everyone knows everyone else — or, at the very least, their names. The truth is that everyone has their secrets, the parts of themselves that no one needs to know.

The heart of a good noir, then, is uncovering those deeply repressed secrets. This is true of works like Brick, which moves the noir to the community of High School students with their own cliques, secrets, and cruelties. Equally, the history of noir going all the way back to at least The Maltese Falcon has a tight connection with queer fiction. In the 1940s/1950s, when noir cinema was at its peak, homosexuality was, to say the least, not in vogue. Oftentimes suspects were painted with a queer subtext to make them more suspicious to our square jawed American detectives.

The more interesting texts, however, engaged with the queerness of the detectives, though these noirs often came out after the height of noir cinema. Cruising, for example, has its lead detective slowly discover the full extent of his own sexuality in a rather problematic but fascinating way. James Ellroy’s The Big Nowhere, likewise, uses the queerness to confront the detective’s own view of himself (albeit to a tragic end) as well as the context of the era of McCarthyism.

While not set in the 40s/50s, Mariko Tamaki and Nicole Goux’s This Place Kills Me likewise utilizes the noir implications of queerness to a startling degree. Set in an all girl’s private school in the 1980s, This Place Kills Me follows a new student named Abby Kita with secrets of her own, as so many noir detectives do. As with the noir detective, Abby is a figure of scorn in her environment, always at odds with the establishment and faculty as well as the various cliques running the halls.

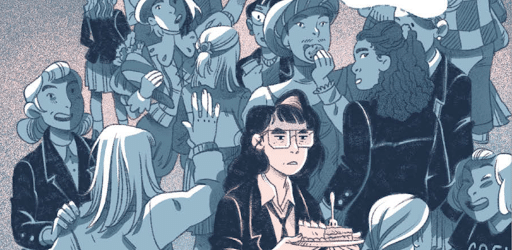

This is nowhere as prevalent than in the show stopping opening sequence. Here, Goux draws Abby alone in a sea of people, navigating the various party goers who all talk about her, even as they actively try not to talk to her. Goux’s use of framing and color constantly highlights Abby’s isolation, be it by having everyone shaded in blues and Abby in pinks or highlighting her path walking around the crowd.

At the same time, Tamaki’s skills as a writer highlight the moral rot at the heart of Wilberton Academy, but in such an incidental way as to make the reader forget it in the tangled web of self-loathing, conspiracy, and homophobia. We can see this in the dynamics and hierarchies of the students and school. The sequence begins with Abby being looked down upon by her roommate before that very same roommate is ignored by the popular girls who are, in turn, condescended to by the faculty.

Furthermore, Tamaki paints her various characters — both investigators and suspects — with an empathetic brush. That is not to say they are all sympathetic; even characters we’re meant to align with morally have their weak points and cruelties. But rather, Tamaki makes the reader understand who these girls are as people. She does this not through long monologues about the nature of their character, but rather through small, intimate moments coupled with Goux’s character designs and acting.

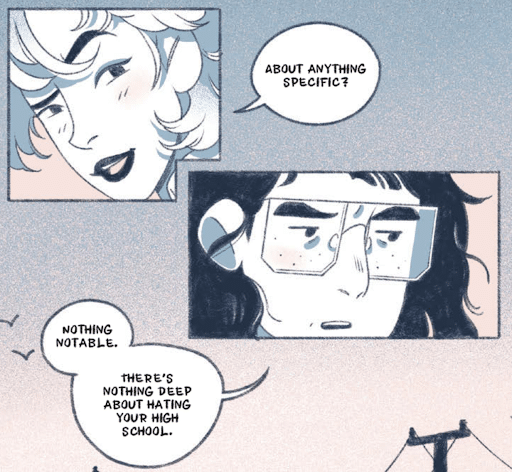

Take, for example, the murder victim: Elizabeth Woodward. We only see her alive for ten of the book’s roughly 300 pages. And yet, we get a portrait of her. Our first moment with her is a single page spread. Much like Abby, for all that everyone is talking about how great she was, no one is actually talking to her. Goux draws this introduction to have Elizabeth centralized in the image — spotlit like the movie star her peers compare her to. At the same time, she is boxed in by her fellow students, not allowed to move from outside the spotlight as her pained expression clearly highlights she wants to.

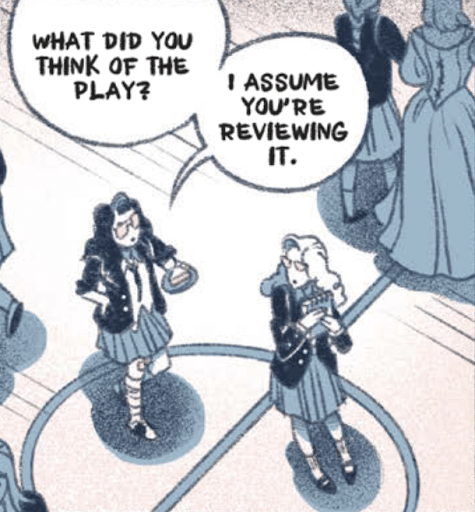

But when Abby actually does talk to the girl, we can see a fuller picture of who Elizabeth was. Not anything specific about her home life or her friend dynamic or even the dark secret she had uncovered. But rather, we get a sense of a frustrated young girl trying to figure out her place in a world that hates her and tells her she should hate herself too. Tamaki’s script highlights a lack of full connection between the two girls, often having panels highlight their separation. But you can feel a small connection between them, even if it’s just in this moment.

What’s more, there’s a sense of the tension within Elizabeth in that introductory splash page being unwound when talking to Abby. She doesn’t need to pretend with the girl, even as she is still caught in a web of conspiracy that goes to the absolute top. She can just be and express a dissatisfaction with the systems of the world. Even as she’s boxed in, she can be free. We, the readers, can hope that there was another way this could’ve ended, even if it’s clear there wasn’t.

There is often a fatalism to noir. That the events that happened could not be avoided. That perhaps they shouldn’t be avoided. Not that the people needed to die the deaths forced upon them, but rather the cruelties at the heart of the world needed to be expunged. That the tower of cards simply could not stand forever, and that trying to keep things the way they are can only result in more cruelty.

This Place Kills Me is a fantastic work of YA Noir that highlights the strengths of that genre in a way that engages with the implicit queerness of things. Ic, both out of petulance and as a means of escaping the cruelty of the world around them. It’s a thrilling story highly worth recommending.

This Place Kills Me is out this month via Abrams

Read more great reviews from The Beat!

!["Superman" (2025) Brings Heart, High Stakes, and Surprising Twists [SPOILER-FILLED REVIEW]](https://www.supermansupersite.com/Superman_2025_Retro_Poster.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·