“Honestly, the closest I can think of [MCU films], as well made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks. It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.” — Martin Scorsese, EMPIRE Magazine, 2019.

Yes, that’s right. This essay is yet another belated fan-ish response to Martin Scorsese’s remarks on MCU superhero movies– which remarks can, with some fairness, be extended to all superhero movies– as to whether they belong to “the cinema of human beings.” It’s also another “best hundred” list, much like Scorsese’s list of favorites in 2022, though he upped his count to 125 in that one. (And yes, I know he’s got a longer list too, but I’m going to reference the one that comes closest in range to my own.)

So, even on a list of the one hundred best superhero movies, are the majority of them comparable to the thrill rides one finds in amusement parks? Possibly, if one thinks only that they’re both focused on kinetic situations that suggest peril (the rollercoaster) or confusion (the house of mirrors). But possibly not, in that people participating in theme-park attractions are generally their own personal thrills, or, at a stretch, the thrills of associates in their company, of people they know. But even superhero movies require the audiences to identify with people on the screen as proxies, and that’s where the comparison breaks down– just as it would if one were attacking the more “thrilling” movies on Scorsese’s best 125 list– CAT PEOPLE (1942), DUEL IN THE SUN (1946), DIAL M FOR MURDER (1954), HOUSE OF WAX (1953), FORTY GUNS (1957), CAPE FEAR (1962), and the one entry I’d deem “superhero-adjacent,” JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS (1963).

In a later essay, Scorsese admitted that Alfred Hitchcock in particular was a master of “thrills,” but he also claimed that the audiences came to Sir Alfred’s movies for other things besides thrills. For every film on my list, I will show something in addition to thrills that makes these super-flicks attractive.

Now the superhero genre has one big problem that one doesn’t encounter in westerns, horror films and suspense movies. The problem is not that superheroes have no human relevance– if they did, no one could identify with them, even minimally– but that the heroes run around dressed in attire completely out of step with the fashion of the times. Dozens of film-characters, whether adapted or original, are “superhero-adjacent,” but most of them wear the clothing appropriate to their cultures. Jason wears what the well-dressed Greek warrior should wear, Buck Rogers has his au courant jetpack, and Tarzan sports only the finest anthropoid apparel. Tarzan and Buck Rogers don’t get a whole lot of respect, but no one makes fun of their clothes– or lack of same.

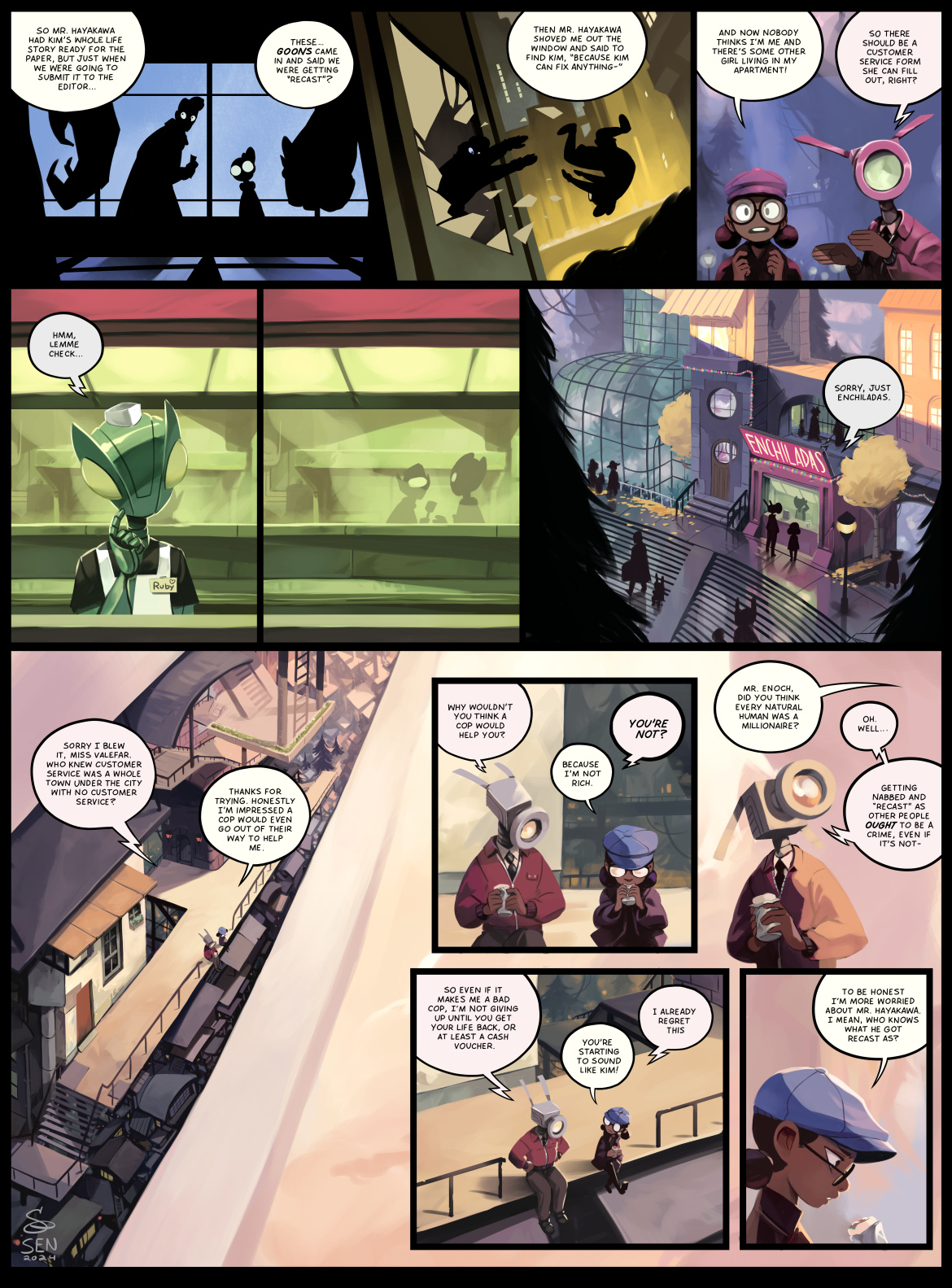

The outfit of the superhero– whether it’s a literal costume, or a physical form that looks like a costume (Hulk, Hellboy, the Ninja Turtles) — gets no respect from critics because the costume is a middle finger to standards of naturalistic representation. In support of that defiance of consensual reality, all the film on my “top 100” feature what I have termed (in my blog THE GRAND SUPERHERO OPERA, plug plug) as “costumed crusaders.” That means no heroes who wear either space-gear, or lionskins, or business suits– unless they’ve got something along the lines of a domino mask as an add-on. So, no heroes who just wear big floppy hats (Judex from 1916) or big black dusters (Blade from 1998). And since the crusade for the public good is almost as much a fantasy as fighting crime in a costume, I exclude outright villains even when costumed, be it Fantomas or the Suicide Squad. Some monsters meet my criteria as crusaders (the aforesaid Hulk) and some don’t (Swamp Thing– not that he has a really outstanding feature film anyway).

I define a “feature film” as being at least an hour long. There’s no upper limit, though the longest films on the list are about four hours, all of which are multi-chapter American serials. I include television films as long as they actually premiered on television as movies. The pilot for THE INCREDIBLE HULK program first appeared in a slot for a television movie, even if the film later got chopped up into two separate episodes for series-syndication. But if the show’s producers took some two-part episode and schlepped it out to video stores as a “movie,” that’s a big no. Same thing for compilations of whole serials into feature-film length. The list includes animated movies in addition to the live-action entries.

Each entry for each choice will get a paragraph to explain what’s good about it. Since that would make a very long single post, the current plan is to follow this prelude with ten posts, each of which will have ten alphabetically arranged choices. Anyone interested in arguing about things I’ve left out, or about things I ought to include down the line, is welcome to kibitz.

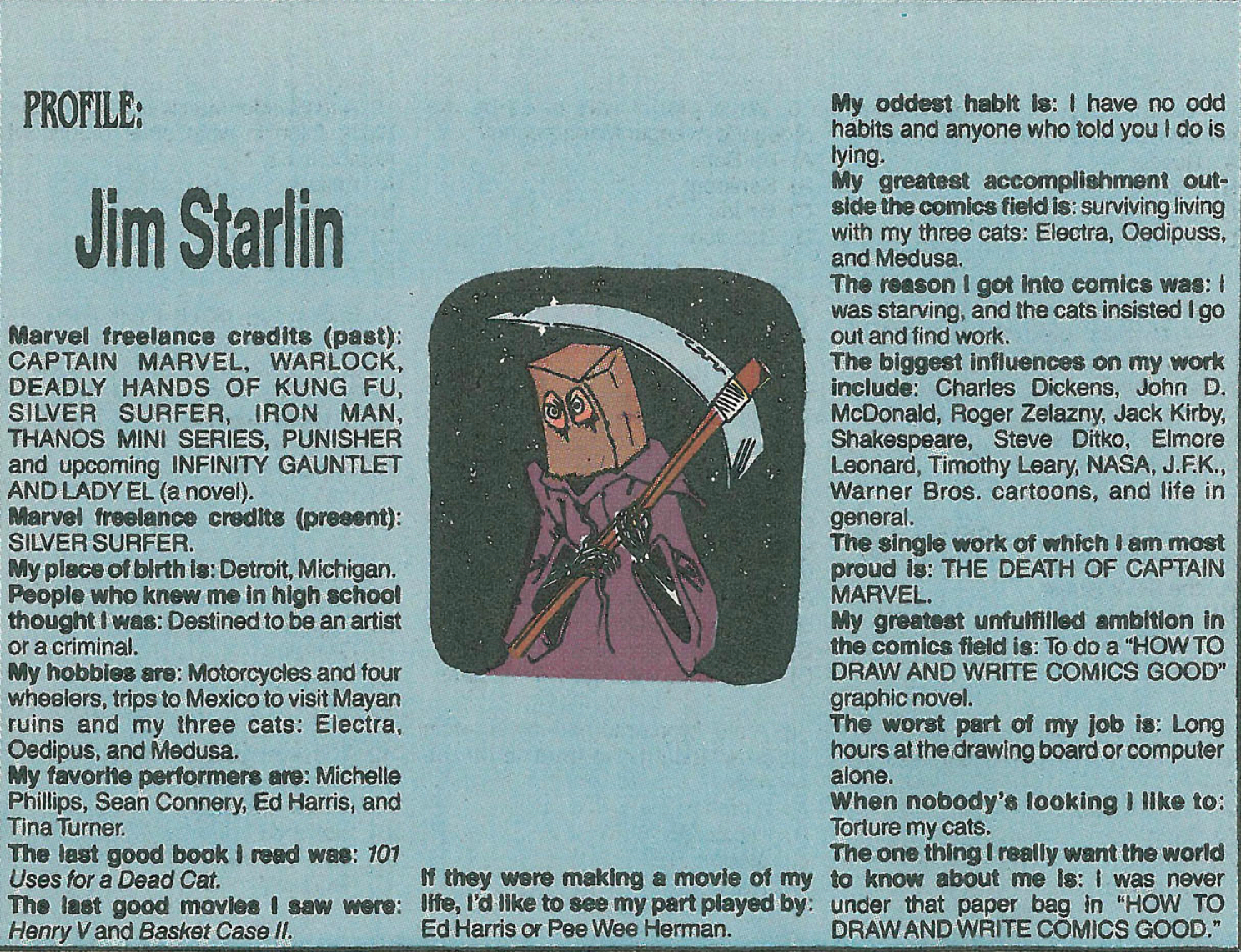

The upshot is that I think superheroes in all their manifestations have displayed fascinating creativity, and not just in some freak-show manner, as certain elitist critics have argued. We don’t have a canon for the genre in any medium, and there may never be one. My list includes things like dusty serials, not because I think anyone reading this will start poring over twelve chapters of SPY SMASHER, but to serve as my personal celebration of excellence, even for movies whose budgets wouldn’t have provided craft services for an MCU flick. People who love genres always love them for their history as much as for their most exceptional accomplishments.

As for a list of what I think is exceptional, and why– I’ll get to that in my next post.

*****

![Kid Heroes & ‘Lumpia’ Return to San Diego Comic-Con 2024 with Exclusives, More [UPDATE July 8]](https://sdccblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/SDCC24-Snapback-360x360.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·