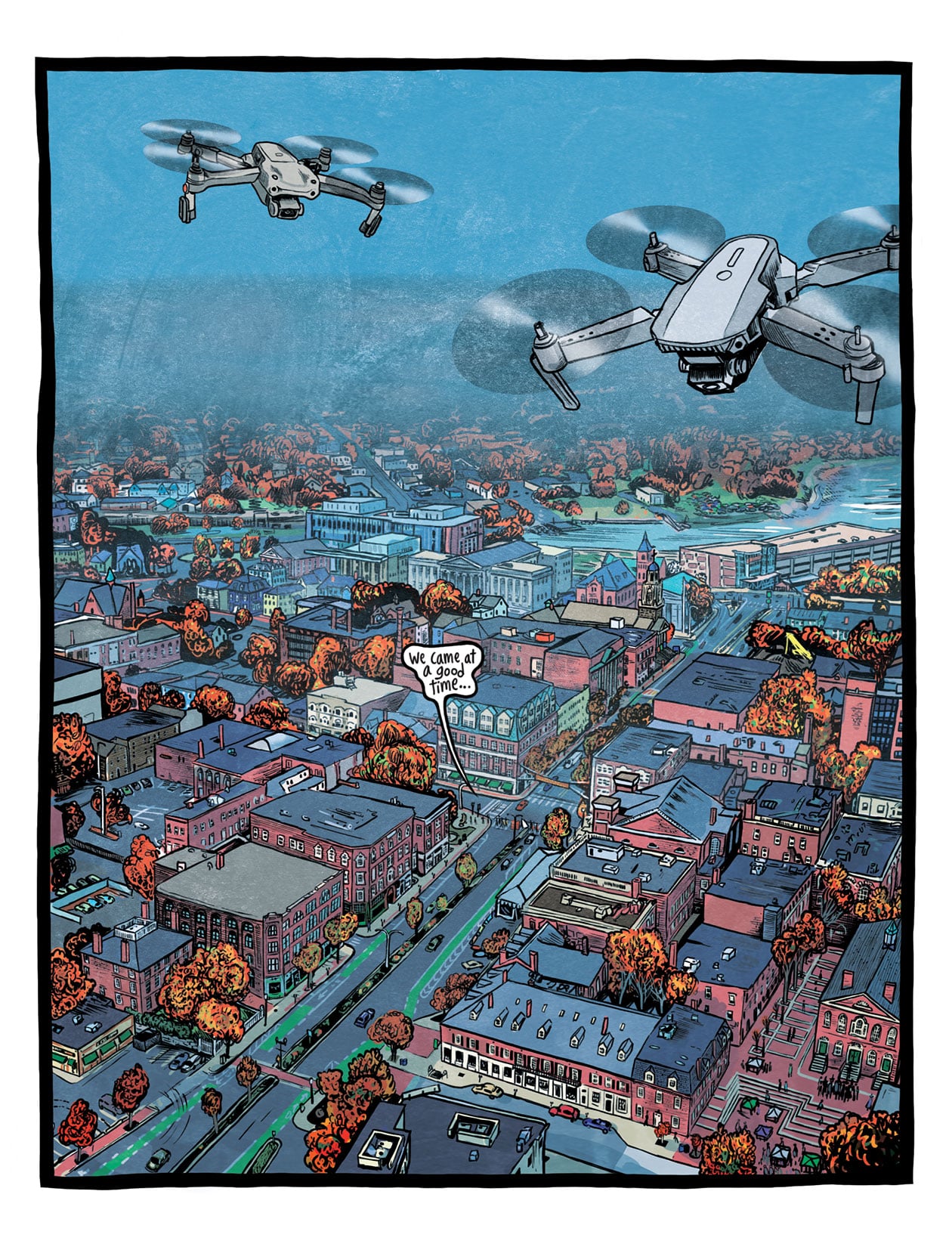

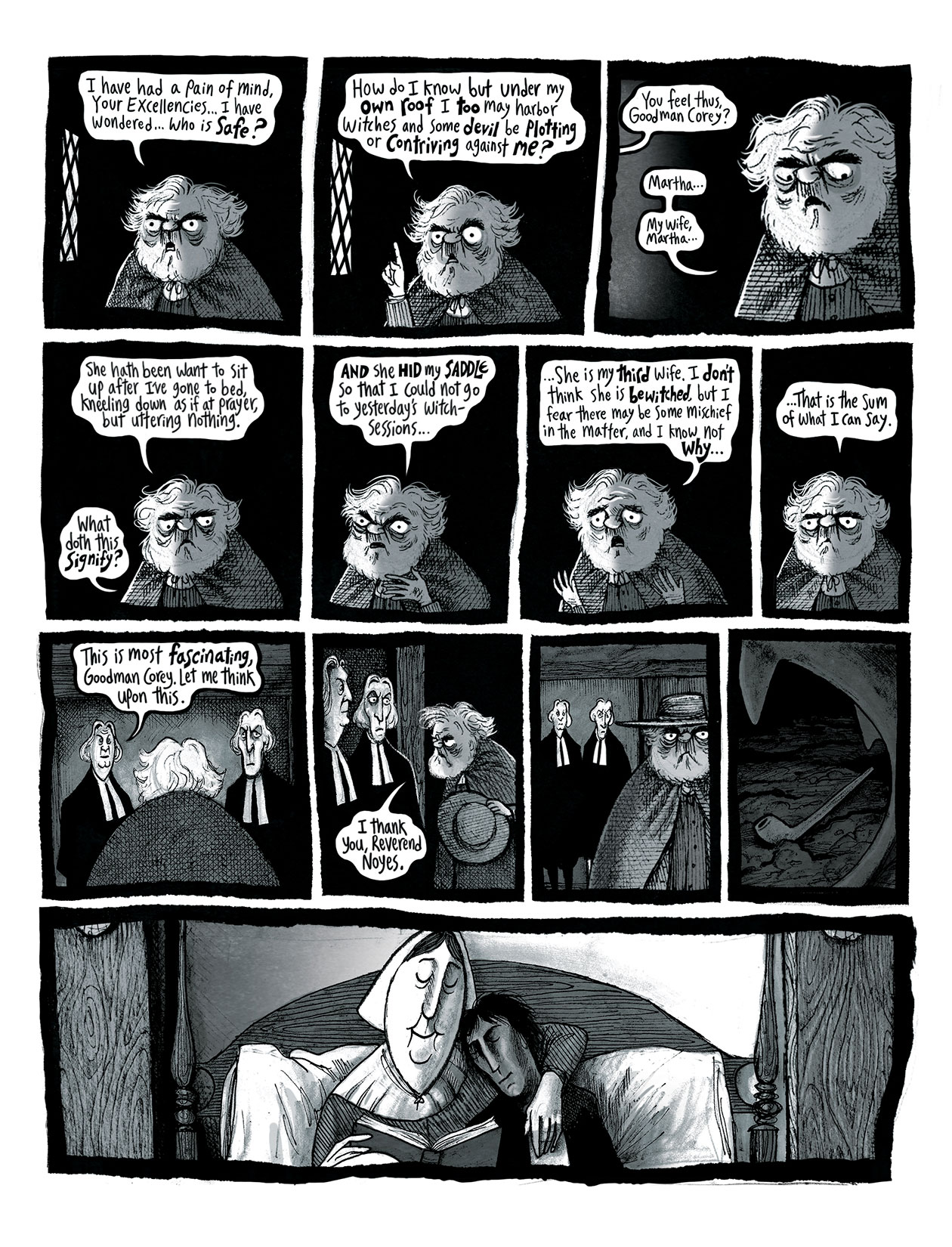

Known for his macabre visuals and hauntingly expressive characters, Ben Wickey is no stranger to bold storytelling. Now, he’s turning his eye toward one of the darkest chapters in American history in his first full-length graphic novel, titled More Weight, a searing, visually arresting reimagining of the Salem Witch Trials that dives headfirst into the psychological and societal tensions of 1692 and brings a fresh, visceral energy to an important historical event that’s often been reduced to moral allegory.

In this exclusive interview, The Beat sat down with Wickey at San Diego Comic-Con 2025 to talk about More Weight, the challenges of adapting real history into a graphic medium (maps, and lots of ’em!), and what readers can expect from this haunting new work.

Photo Credit: Ben Wickey

Photo Credit: Ben WickeyOLLIE KAPLAN: Can you introduce yourself to our readers?

BEN WICKEY: My name is Ben Wickey. I’m a cartoonist, animator, and the author of More Weight, which will be released in September 2025.

KAPLAN: Can you tell me a little bit about your creative journey? Wasn’t your first graphic novel with Alan Moore?

WICKEY: What happened was that for about 10 years, I’d been working on this graphic novel about the Salem Witch Trials called More Weight, and doing animation, too. I made animated films and other things at CalArts and worked on Marcel the Shell. Still, always in the background, I was working on this kind of labour of love about the Salem Witch Trials, which is such a departure from things I usually do, because it is a very dark, bleak book. Usually, I do very fun, light-hearted things, and this is not that.

It was a thing that I started very simply. In high school, I saw a play by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow about Giles Corey, an 80-year-old farmer who was pressed to death in Salem in 1692, and basically, I said, “Oh, I should do a comic book version of that play.” But of course, over 10 years, the more I researched, the more it became my book because it became something I was passionate about. Around the winter of 2019, I felt very discouraged because I thought, “Who wants to read a book about the Salem Witch Trials in which there are no witches? Who wants to read this dark, heavy thing? I’m hundreds of pages in and don’t know where I’m going. I should write to Alan Moore.” This is not just because I was doing a comic book, but because Giles Corey, the main character of my book, comes from Northampton, England, where Alan Moore famously grew up and currently lives. So I sent him a letter to his house, basically saying–

Photo Credit: Top Shelf

Photo Credit: Top ShelfKAPLAN: A physical letter?

WICKEY: Yes, it has to be. I don’t think he has an internet connection. At that point, he was publicly retiring from comics, so I sent him a physical letter basically saying, “I’m doing a comic book; however, that’s not why I’m talking to you. Corey, who was pressed to death in Salem, led one of the first documented protests in American history.” Corey came from Northampton, and, of course, he is mentioned in Moore’s books, Providence and Jerusalem. And so, Moore knew that Corey was from Northampton, but I don’t know if he knew quite so much about the impact that this very gruesome death had upon America, on American history.

A few weeks later, Moore wrote back; it was a longer letter than I had sent him. And this was one of the best letters I’d received. He said, “I can’t wait to look at your book. Here’s what Northampton would have been like when Corey was growing up, there were heads on spikes, and there were all these different things. You should show this, you should show that, and you should do this.” It was such an encouraging shot in the arm for me. That was early, like January 2020.

Photo Credit: Top Shelf

Photo Credit: Top ShelfThen, in February 2020, I moved to Los Angeles, California, to work on the Marcel movie. I’m from Massachusetts, about 30 minutes north of Salem. I moved in with my now wife, Mariana Yovanovich, and then COVID hit, and we were all sent home. So I thought, “Oh, I should just cut my book in half and self-publish it,” like get it printed as a physical copy, part one of More Weight. And so, I sent it to Alan in the mail, along with a copy of a book I’d done with Ki Longfellow called The Illustrated Vivian Stanshall: A Fairytale of Grimm Art.

In the spring of the following year, his wonderful assistant, Joe, got back to me and said, “Oh, Alan apologises for not writing back. He’s doing The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic, and he wants to know if you have the time or interest in doing 50 pages of comics.” And I thought, “You don’t say no to that. No, no, no, no, no.” So, that was amazing. I didn’t expect to get a job from him. I didn’t expect anything from him because he was publicly retiring from comics. So, it’s not like I had any expectations or presumptions that he would give me a job as an illustrator to do comic book art. And I, like the rest of the world, was waiting for that book, the Bumper Book of Magic, to come out. I was like all the other fans, wondering, “When will that book come out? That’s going to be great.” So, through 2021 and 2022, I took a break from More Weight, which was a good, much-needed break. That came out through Top Shelf, and they took an interest in what I was doing and what else I was doing. I said, “Well, I’ve been writing this book about the Salem Witch Trials, which will probably be 500 pages when it’s done.”

Photo Credit: Top Shelf

Photo Credit: Top ShelfKAPLAN: Can you explain that a little more for people unfamiliar with the influence and the play?

WICKEY: Longfellow was like the rock star of the 19th century, back when poets were the equivalent of rock stars. And he was America’s premier poet. As far as European people were concerned, if you’re thinking about American poetry and what it offers, you think of Longfellow. Subsequently, people like Edgar Allan Poe thought he was overrated. And, you know, of course, Poe believed that because, as we know, he had a bag of chips on his shoulder. But, of course, we know Longfellow from “Paul Revere’s Ride,” “The Song of Hiawatha,” “The Village Blacksmith,” and things like that.

When I was in high school, we read The Crucible, like so many American high schools do, and we had an assignment. My excellent English teacher, Julie Calzini, said, “Your assignment is to take a character from this play that you find interesting and create a piece as that character.” I chose Corey because he seemed to be such a strange, rambunctious, mischievous person. I like crusty older people, you know? I like feisty elderly people. It’s just my thing, and I like drawing them. So he appealed to me on a deep level.

And so, I looked around for other material, not just Arthur Miller, but who else had something to write about Corey. Sure enough, I found this play, a play by Longfellow, which was very weird because he didn’t really write plays. In 1868, he wrote a book called “The New England Tragedies,” a collection of two plays—one is John Endicott, about the Quakers’ persecution, and the other is Corey of the Salem Farms—and it’s bleaker than his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne would get when talking about 17th-century Puritans. I mean, he got into the character of Corey in this very bleak, not quite nihilistic, way. Still, it’s a massive departure from the kind of moralizing, optimistic work he had done previously. So part of More Weight also involved me trying to figure out what happened to Longfellow in that decade, you know, the U.S. Civil War, the death of his wife. And I realized that Corey was a character who appealed to him personally, and I wanted to explore that.

It started, as all menaces to one’s life are, simple enough. I decided to illustrate this play. I wanted to do a comic book version of it for fun. And then, you do a little bit of research and go, “Well, of course, I have access to information that Longfellow didn’t have.” Okay, well, Corey didn’t live on the Ipswich River. All right, well, I’ll change that bit. Or, well, this didn’t happen the next day; it happened months later. All right, well, I’ll change that and make it months. Over time, the more I researched (and I researched as I drew), I became more obsessed and impassioned about the facts, which are far crazier and infuriating than anything Miller could make up, and they’re so overlooked. This incredible, frustrating, barbaric history of not only what happened in Salem that year, but also the whole aftermath that we don’t talk about. It had consequences. Usually in movies or TV shows that deal with it, after the last people are hanged, everybody gets sad, and then they go home, and that’s the end. But this event had enormous consequences on Salem, where it happened, and American history, and I wanted to explore that. And so, the Longfellow bits got smaller and smaller as I went, and my bits got more and more.

Then, when I was halfway through, a cousin in Michigan said, “Oh, by the way, we’re descendants of Mary Eastey, one of the last people to be executed.” So, then it became personal. It felt like an obligation, almost, without getting to whatever about it. But it did feel, at that point, “Oh Jesus, this is family now,” and I have to explore this.

Photo Credit: Top Shelf

Photo Credit: Top ShelfKAPLAN: Then, I want to hear more about Salem as a character in and of itself.

WICKEY: It begins with a whole kind of acceptance of this history.

KAPLAN: I didn’t know you grew up near Salem, and I would love to hear more about that. I’ve talked to others who write Salem stories, and much research is involved in accurately telling them, often including travel to Salem itself. But then, the town also has this weird relationship with its history and mythology because it also brings in these tourists.

WICKEY: I grew up in Rockport, Massachusetts, a fishing village about 30 minutes north of Salem. And Salem, to me, is just a place I’ve always visited. It’s one of my favorite cities. Oh, and as a descendant…even before I knew that, Salem was just a place with this wonderful microcosm of spookiness. It’s its own planet, but it’s also where most of my friends lived when I was growing up, so I always looked forward to going there.

It wasn’t until I went to middle school in Danvers, Massachusetts, which, in 1692, was Salem Village, ground zero for the beginnings of this witch panic, that I started to learn more. My middle school was in a 17th-century farmhouse, so it was the perfect area to seriously learn about what happened in 1692. And of course, if you’re going to middle school in Danvers, where will you go for field trips? You’re going to go to Salem. That’s the closest place with all the museums and things to see. So, I remember being a teenager, standing under this giant, wax figure of Corey. He’s bald, has a long beard, and is short, like Danny DeVito-size. It was sort of my introduction to him, and I don’t know, but it captivated me. Who is this guy, you know? I think that the wax figure is still there.

I grew up wandering around Salem, and it was tame. But increasingly, October tourism has gotten so big there. I think over 1.3 million people came just in October alone last year, and it’s a tiny city designed in the 17th century, when you could fit all of New England in Fenway Park. However, people treat it as a witch theme park, and they forget that people live there, and God forbid, they need an ambulance in October. Traffic is horrible. I know some people who had to park half a mile from where they live because they couldn’t find parking near their house.

But of course, I do creepy stop motion films. It’s not like I don’t like spooky things. I love that kind of thing, and Salem’s my favorite city, and Halloween’s my favorite holiday. But there was always this kind of nagging thing in my conscience, of like, “All right, but none of this stuff would be going on if 25 innocent people hadn’t died. You know, 19 men and women were hanged, five people died in prison, including a newborn baby, and one man, Corey, was pressed to death.” So, I was wandering around like anybody going there, asking, “How did this come to be? How did this happen?” And so, one of the book’s last chapters is the aftermath, between 1692 and early this year, of everything that happened in terms of how Salem has dealt with its history in different ways.

Photo Credit: Top Shelf

Photo Credit: Top ShelfKAPLAN: Why is it important to retell the Salem story in the current political climate?

WICKEY: This story must be told to every new generation. Many of the facts are infuriating, so you read it, and get angry, and there are so many notes at the end to say, “No, I have proof of this. It comes from this document.” Sometimes it’s just too much to stand when reading about this. I believe that we kind of, as Gore Vidal said, “We live in the United States of amnesia.” We as Americans remember what is convenient for us, and we mythologize Salem to the point where, because the word witch is involved, and witchcraft is a man-made thing, it’s like a thing that’s out of Scooby-Doo. We don’t think this happened; that innocent people were involved. People can distance themselves. They don’t have to think about it; there’s a distance between these two things. What happened in Salem is, I believe, America’s clearest example of what happens when a community can tear itself apart. What happens when a community fails, when a society fails, from petty vengeance, hatred, intolerance, and all the things we’re seeing now.

This is an incredibly relevant time for this book, and I don’t think it’s right that we gloss over what happened here. I sometimes feel like there are lessons to be learned from this that are sometimes squandered. Opportunities to teach this story in an empathetic way that demands that you, as human beings, empathize with these people. Sometimes Salem has a weird blend of pseudoscience and pseudohistory that has stunted the city from reaching its true height. If any town could say, “No, no, no, we should stand for evidence and critical thinking. We should stand for enlightenment principles that we take for granted,” it should be that city where superstition’s bloodiest American victory took place. We can’t forget that history doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It happens in our backyards, and everything has a place.

I hope this book is helpful whether you live in Salem or are visiting. You can almost use the book as a guide. I tried to follow the topography to the point where you can tell where things happened. My wife, Mariana, did the maps at the front of the book, which are incredibly helpful for anyone who wants to visit all the locations and sites and see what’s still there and what isn’t, to reconnect and realize that this happened, real people suffered, and this still means something. It will never not be relevant.

Photo Credit: Top Shelf

Photo Credit: Top ShelfKAPLAN: I was struck by how timely it felt. I’m trans, and it felt so timely to read this right now because it feels like a similar thing is happening, not just to our community, but across other communities too, of this villainization of others by supposedly religious people.

WICKEY: Exactly.

KAPLAN: Rather than getting on my high horse, I want to discuss the maps and that collaborative process with you and Mariana.

MARIANA YOVANOVICH: Ben was overworked. I work in animation as well. We met in college, actually, at an animation college. But before that, I went to architecture school. Back in my country, one of my research projects was to draw maps of cities and how much green space there was in them. So, he was overwhelmed by the maps, and I said, “I got this. I did a lot of that for a lot of years.” When we return home for Christmas, we visit Salem every year, so I know the stomping grounds pretty well. I go back and forth with him, so it was a pleasure to help out a little bit besides taking photo references around the city.

KAPLAN: There are certain photo references that you helped with, too?

YOVANOVICH: I found Ben in the middle of the night in the kitchen wearing period clothes and posing for photos. So yeah, I also did reference pictures and things like that.

WICKEY: I’ll be here at 3 a.m. stomping in our apartment, with a full suit and big dress shoes in the kitchen. We live in L.A., too, and I’m usually sweating. And then, the cat’s going around, and he’s like, “Get out of there, get out of there,” like with the timer. [Laughs.]

Photo Credit: Top Shelf

Photo Credit: Top ShelfKAPLAN: Can you tell me more about the research process, which I think you both can speak to in different ways?

YOVANOVICH: Ben found the original maps and was really happy about them.

WICKEY: Our biggest challenge was that back then, maps weren’t always that accurate when doing land topography, so we had to be careful with the landmarks and where they would meet because rivers move. Also, we have a more accurate position of things with Google Maps. But back then, they didn’t because the Earth is not flat. Newsflash, Earth is not flat.

It isn’t easy to do the topography. So for us, it was a lot of back-and-forth, like, “Okay, this river was here and got moved there. Some blocks in Salem are still pretty solid where they are, so we can pinpoint from there.”

YOVANOVICH: And Ben found out that some places are not quite what they used to be.

WICKEY: Yeah. Massachusetts has had lots of land-making since the 17th century. The outline of Boston looks nothing like it would have at the time. Likewise, with Salem, the South River used to come up to a place in Salem called Front Street because it was the original waterfront. But now, you can walk around that area, no problem. So I did full-page illustrations in different regions from the same angle to see what had changed. The funny thing is, the layout of the streets and roads hasn’t changed much, but some houses have been moved—literally the whole house.

Photo Credit: Top Shelf

Photo Credit: Top ShelfYOVANOVICH: But also, there were locations that Ben said back in the day they thought, for example, that some people were buried in a specific area, or where one or the hangings happened, it happened where a Dunkin’ Donuts gas station is now.

WICKEY: Before, they thought it was in another location. People were executed on a place that in 2016 was finally confirmed as the spot called Proctor’s Ledge. And now, there’s a memorial because so much new stuff has come out of Salem in the past 10 years. Before that, it was just known as a place called Gallows Hill, which was like a larger hill, sort of further behind this Ledge, because all of this stuff was intentionally forgotten. Salem was a shameful event. And so it’s not just forgetfulness, but it’s willful forgetfulness.

We have the documentation of the preliminary interrogations that happened in the spring of 1692, and they read like a play. It’s question, answer, question, answer. They’re harrowing and riveting, and these people come to life when you read these documents. I’ve handled a few, and there’s no experience like handling actual documents like this. They come alive in your hands.

There is no record book from the actual court; that does not exist anymore. We don’t have about 11 documents, and it makes you wonder, “What happened to those? Where did that go? And what do they contain?”

Photo Credit: Top Shelf

Photo Credit: Top ShelfKAPLAN: Maybe they’re like Emily Dickinson’s letters and will suddenly be discovered one day.

WICKEY: The thing about it is, these were Puritans. I don’t know if they would have burnt the documents because they have this idea of God’s eye always being on them. But I don’t know.

Check out more preview pages from Wickey’s graphic novel, More Weight, below:

Photo Credit: Top Shelf

Photo Credit: Top Shelf Photo Credit: Top Shelf

Photo Credit: Top Shelf Photo Credit: Top Shelf

Photo Credit: Top Shelf Photo Credit: Top Shelf

Photo Credit: Top ShelfLearn more about where to purchase More Weight by Ben Wickey here.

Stay tuned to The Beat for more coverage from SDCC ’25.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·