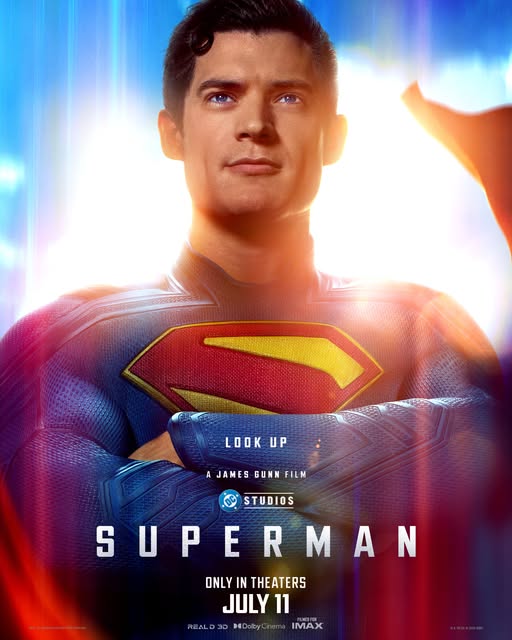

Andrew Farago | May 19, 2025

Jackson “Butch” Guice, one of the most acclaimed comic book artists of his generation, passed away on May 1, 2025, after a prolonged bout with pneumonia. He is survived by his beloved wife, Julie, and their daughter, Elizabeth Diane.

Guice was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and grew up on a steady diet of classic adventure comic strips, comic books, and sci-fi movies, and was especially fond of the films of stop-motion animator and special effects master Ray Harryhausen, whose works directly influenced several of Guice’s own projects, including his 2015 Olympus graphic novel, published by Humanoids.

The precocious artist decided on his career path at a young age, and made a name for himself in fanzines, contributing several covers to The Comics Buyer’s Guide, beginning in December 1977, when he was 16 years old. Through his fanzine work and networking at comic book conventions, Guice caught the attention of editors, publishers and artists, and in 1982, he landed his first professional work, an uncredited assistant to penciler Pat Broderick on Marvel’s Rom Annual #1 as well as his first ongoing series, The Crusaders (rebranded as Southern Knights with its second issue), a self-published comic created by the husband-and-wife writing team of Henry and Audrey Vogel.

An issue of Comics Buyer's Guide featuring cover art by Guice.

An issue of Comics Buyer's Guide featuring cover art by Guice.“Butch unintentionally taught me a lot about scripting comic books,” said Henry Vogel. “My script for the first six pages of Crusaders #1 (aka Southern Knights #1) was intentionally terse, with little in the way of descriptions or flavor text.

“When Butch was inking those pages, he added more dialogue and some great flavor text. His additions made the opening scene much better. I took what he showed me, and ran with it. He didn’t ask for any credit, nor did he make a big deal of it. But his scripting contribution showed me what I was doing wrong with my script. It’s something I never forgot, and I am forever thankful to him for pointing me in the right direction.”

On the strength of his portfolio and his ever-increasing body of published work, Guice got his foot in the door at Marvel Comics. Bob McLeod was one of the first professional artists to take notice of Guice in those early years. “Sometime in the early 1980s I was at a comic con and [Butch] asked if I would look at his sample pages,” McLeod said. “They were very impressive and I couldn’t believe he wasn’t already getting work. I asked him to help me pencil an Iron Man job I really didn’t have time to do, and he did a good job. I showed the pages to my editor, Al Milgrom, and he went on to have a great career.”

His work on the Rom annual impressed series writer Bill Mantlo, who encouraged Milgrom to offer Guice a tryout on another Marvel toy tie-in, Micronauts. Guice passed the audition and would pencil the series for eleven consecutive issues, #48-58. The prolific young artist also contributed a pin-up section to Marvel Fanfare and several entries for The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe, as well as the X-Men and the Micronauts limited series, along with several fill-in issues and guest spots through 1983 and 1984.

A two-page sequence from Swords of the Swashbucklers.

A two-page sequence from Swords of the Swashbucklers.The in-demand artist was tapped for increasingly high-profile and varied projects, including the official Marvel adaptation of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and the Marvel Graphic Novel The Swords of the Swashbucklers, written by Bill Mantlo, so Guice reluctantly had to step aside from Micronauts, although he knew that he was leaving the series in good hands.

“In 1982 Marvel hired me out of the blue to be the regular inker on Micronauts,” said Kelley Jones. “Really, it was Butch who hired me, Marvel just made the offer. He liked a couple pinups I did over him and that was all he needed. I had no track record or anything. He just liked what he saw. I was thrilled beyond belief as Butch was becoming a star and when the incredible pages he drew arrived I simply froze. I turned in the first ten or so pages and the reaction from the office was cool to say the least."

“Butch called me and I expected the worst. Butch had another trait I loved, he told the truth. He didn't mince words,” Jones continued. “I wasn't good on those pages. Yes, he acknowledged the lackluster work I did but he went on to press the point — he went through the same thing himself when he started drawing the book. ‘Just make it your own, and I'm on your side,’ he said in his wonderful Shelby Foote accent.”

“The next batch were much better and the final pages made Butch say, ’You have a career in this business.’ If not for his support and understanding I would have crashed and burned. Such calm patience with a new untried artist was amazing but not as amazing as the fact he wasn't much older than me yet so mature about it all.

“His art stunned me as it had no under drawing, no hesitant sketching it out. It was just drawn, and drawn perfectly. His natural talent was immense but not as big as his incredible imagination. Butch could draw anything and when I'd ask him how he did it he simply said it's what we're born to do.”

When Guice, a self-described restless artist, left Micronauts to pursue other challenges, Jones was concerned that his own fledgling career would end with Guice’s departure, but thanks in part to Guice’s recommendation, he was offered the opportunity to pencil Micronauts the following month. “I called Butch and said I’d taken the job but now was regretting it because I really didn't know how to produce monthly work at a level that readers would expect,” Jones recalled. “His kindness was now even more marvelous to me at that time. He calmly said he'd talk me through it and to call him with any questions but take the job and make it my own. So for the next few months Butch tutored and advised me with all kinds of insights that I use to this day in making comics.

“Years later I was drawing Batman monthly for DC and I got an envelope in a package of scripts and make-readys and such. It was from Butch and all it said was, 'I told you.' I'm grateful to have got to make comics all these years and I'm really grateful my first real experience on how great it can be was because of the big heart of Butch Guice.”

A dramatic Guice-drawn sequence from the first issue of X-Factor.

A dramatic Guice-drawn sequence from the first issue of X-Factor.Among the opportunities that Guice explored after Micronauts were several titles published by First Comics with writer Mike Baron under the editorial guidance of Mike Gold, including Badger, Nexus, and the Michael Moorcock sword and sorcery series The Chronicles of Corum. This work allowed Guice to showcase his artistic range beyond superhero adventures, although he maintained a strong presence at Marvel on titles like The New Mutants and the launch of X-Factor, a series that reunited the original X-Men for the first time in more than a decade, under the guidance of writer and inker Bob Layton.

“I met Butch early in his career when he was penciler on the Micronauts,” said Layton. “It was one of those chance meetings where the two of us became instant friends. Of course, we immediately wanted to team up on a few projects.

“I lived three blocks from the Marvel offices in Manhattan at the time, so I offered my couch as a place for him to crash when he visited NYC from his abode in Asheville, North Carolina. One evening, while hanging out at my place, I asked the easy-going Southerner if ‘Butch’ was his real name. He replied that his given name was Jackson. Since he was beginning his Marvel career, I implored him to use Jackson as his official pen name. I said it sounds classy. I said that I could see an art book in his future entitled ‘The Collected Works of Jackson Guice.’ So, he did … to his eternal regret.

“From that point on, fans started writing letters to Marvel asking if Butch and Jackson were related or maybe even brothers? Needless to say, after almost a decade of confusion, Jackson Guice quietly disappeared and Butch Guice reappeared.

“In spite of all of that, ‘Butcherhead,’ (as I lovingly nicknamed him) remained a steadfast friend and followed me to Iron Man in 1988 and to Valiant years later where he did some amazing illustrations as one of our best storytellers," Layton said. “Although I’m responsible for giving my pal some really disastrous advice, his friendship and loyalty never wavered. But … he did tease the hell out of me!”

The 1987 cover to Flash #1 with art by Guice.

The 1987 cover to Flash #1 with art by Guice.Guice’s talent, speed, and southern charm made him a favorite with editors, including Mike Gold, who recruited him to illustrate the high-profile relaunch of The Flash in 1987 with writer Mike Baron making former teen sidekick Wally West an all-new Scarlet Speedster for the Reagan era.

“To employ the Ditko standard, Butch’s work speaks for itself," Gold said. “Actually, it doesn’t just speak — it shouts. Working with him was equally enjoyable. His sense of humor and his sense of self made every phone call a joy."

Although Guice’s artistry on Flash met with almost universal acclaim, reader response to the adventures of conservative Republican Wally West was mixed at best. Guice left the title after eleven issues, and Baron departed soon after. By the time he left DC, Guice had already lined up a full slate of freelance work at Marvel, including extended runs on Iron Man, Dr. Strange, Nick Fury: Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., a pair of Fantastic Four annuals, and a brief tenure inking Steve Ditko’s Speedball, as well as short stories for the anthology titles Marvel Comics Presents, Marvel Fanfare and Solo Avengers and an acclaimed X-Factor graphic novel, Prisoner of Love, written by Jim Starlin.

In the midst of this incredibly prolific period, Guice teamed with Gregory Wright and Dwayne McDuffie to reinvent the cyborg Deathlok for a new generation of Marvel readers. “I met Butch as many editors do, by calling them up and asking them to do some work,” Wright said. “At the time he was Jackson ... but he quickly became 'BUTCH.' We hit it off immediately and the first job he did for me was a chapter in Avengers Annual #16 with inks by Kevin Nowlan. He was thrilled.

“I continued to try to work with him as often as possible which of course led to many conversations about just about everything and we quickly became friends. ... Dwayne and I would tap him to create the new version of Deathlok and I'm sure his artwork helped us get that gig."

Guice's cover to Action comics #706.

Guice's cover to Action comics #706.By the early 1990s, Guice was living in Asheville, North Carolina, a mid-sized southern city known for its architecture and thriving art scene. “I didn’t really know who he was, since he kept such a low profile and was really shy, but one day I was at the shop and he had a new book coming out and that shop owner introduced us, and we hit it off,” said graphic designer and publisher Chris Sparks. “By the time I owned my own comic shop, which I did for about five years, we’d meet up for breakfast every couple of weeks and talk, or I’d visit his studio."

“It was a proper studio, too, before the computer age. Golden and Silver Age books just stacked all around, piled up on his shelves. He had the first six issues of Bone sitting around, and that was my introduction to Bone. And he introduced me to so many comic strips, too, like Terry and the Pirates. You just name it, anything around that era, he was so into it,” Sparks said. “It was fun for me as a mid-twenty-year old to learn all this from Butch. His knowledge of strips was just amazing. He always wanted to be an adventure strip artist. We just laughed and joked. Lots of wonderful memories.

“We were lucky to get to know him, and to see issues of Action Comics and Resurrection Man as they were produced, right there on the boards. He’d lay things out in his head, and he made it look so easy. That’s what I enjoyed the most about his work. I know it was a lot of effort, but it never looked that way when you watched him.”

Overseeing Guice on Action Comics was editor Mike Carlin, who was at the helm during the 1992-93 "Death of Superman" storyline that broke sales records and made headlines.

“It was easy to appreciate Butch’s abilities as a draftsman … and I had worked with him as an inker/finisher, at Marvel, as well in the early ‘80s,” Carlin said. “Butch was so reliable and steady, if he agreed to do a job, it was done on time and well.

“When Bob McLeod ended his stint on Action Comics, it was easy to imagine Butch’s realism would go well with Roger Stern’s down-to-earth stories. It was also a plus knowing that Butch was the ultimate team player, which is what we needed on the Superman titles at that time,” he continued. “And when we finally got to doing the Superman Wedding Special, Butch wasn’t on the team anymore but ... [he] came back to do a few pages of inking over a Curt Swan inventory job I had in the drawer, … so that Curt could be ‘at’ the wedding posthumously, too! I knew Butch for over 40 years and it was always easy to work with a friend who happened to be responsible and superlative.”

The four ongoing Superman titles shared a week-to-week continuity, and readers were encouraged to buy each title and follow the serialized storyline through the books’ “Triangle” numbering that guided them from Superman: The Man of Steel to Superman to Adventures of Superman to Action Comics each month. Maintaining continuity between the four titles required superhuman effort from the editorial and creative teams as they essentially published a weekly Superman title, but one where each individual title maintained its own separate subplots and character arcs. Mike Carlin and all four creative teams would gather together once a year for an editorial retreat called “The Superman Summit,” where they would brainstorm, discuss upcoming storylines and spend quality time with their fellow creators.

“Butch first made his mark at Marvel in 1982, as the new artist of the Micronauts series, and his early work is even more impressive when you realize that he was just in his very early twenties,” Stern, his writing partner on Action Comics, said. “About a year later, I got a good look at Butch’s penciled art for an Avengers Annual. On those pages, Guice juggled eight Avengers, a Fantastic Four cameo, and the entire city of the Inhumans — and he made them all look good. As I looked over the pages, the thought kept running through my mind, ‘I want to work with this guy some day!' About five years later, that day finally arrived.

“And in the meantime, Butch just kept getting better and better with each new assignment, whether penciling high adventure, super-heroics, or sword-and-sorcery — or adding his inking prowess to the pencils of Ron Frenz, Paul Chadwick, and John Buscema, among others. It was actually Guice the inker whom I first worked with, back when we both got the opportunity to contribute to Steve Ditko’s Speedball series. Butch gave Ditko’s pencils a sharp, crisp line, enhancing the art without overpowering it. I’m no artist, but to my eye, he made Steve’s art look more like it had back in the days when Ditko inked his own stories on the old twice-up art boards.

“Then, sometime in 1992, Butch ... and I finally got to collaborate. ... We’d been working together for some months before we first met during one of the Superman Summit story conferences. I think it was the summit that was held in Minneapolis in 1993. For about two years we got to create new stories about the Man of Steel,” Stern said. “Jackson’s storytelling was clear and exciting, and it was always a pleasure to script his pages. Also during our run, Jackson somehow found time to ink June Brigman’s pencils on the Supergirl comics I was writing. It was all great, crazy fun while it lasted.

“Almost thirty years later, Jackson and I reunited for a ten-page Guardian story on a Superman anniversary special. Working with him again was a real joy. It felt like picking up right where we’d left off. The only difference was that Jackson had become an even more accomplished artist over the intervening years.”

Writer-artist Dan Jurgens, whose initial tenure on Superman spanned the entire decade of the 1990s, generally worked parallel to Guice, but he fondly recalls one of their rare direct collaborations early in 1992: “Of all the Superman stories I wrote, one of my personal favorites was actually drawn by Butch. It was Superman #64, a Christmas story called ‘Metropolis Mailbag.’ I was buried in deadlines and needed a bit of a break and Butch was nice enough to step in and do it — quite brilliantly, by the way. He gave it a sense of humanity that was critical to the story.

“More than anything, he really was a very nice and kind human being," Jurgens said. "So good to work with— always willing and able to tackle the hard stuff and make things work for those around him. A wonderful collaborator.”

Man of Steel artist Jon Bogdanove agrees with that assessment. “When you study Butch’s storytelling, you see outstanding naturalistic realism, clean, genuine draftsmanship, and taut, cinematic storytelling that was almost terse, and definitely no-nonsense," he said. "It wasn’t showy or stylized. It resisted all the flashy tropes and trends that dates so much of '90s comic art in retrospect. It was staunchly professional, timeless, and always annoyingly great."

“He was a good pairing with Roger Stern," Bogdanove added. "Both men were rocks—reliable anchors that helped keep the team on course, especially in our stormier moments. ... Butch was a good artist, and a good teammate. Whenever the rest of us gather at various "Death of Superman" retrospectives, panels etc, Butch’s absence will be strongly felt.”

Two-page Guice spread from Resurrection Man #1.

Two-page Guice spread from Resurrection Man #1.After three years illustrating DC’s first superhero during the "Death" and "Return" storylines that turned Superman into one of the industry’s top-selling titles, Guice felt it was time to take a break from traditional superhero comics, and he teamed with writers Dan Abnett and Andy Lanning on an original title, Resurrection Man, a dark quasi-superhero tale set within the DC Universe that played to Guice’s interests and his strengths as an artist. Each time the series’ immortal protagonist Mitch Shelley died, he would return to life fully healed and in possession of a new superpower, while losing whichever power he had previously. Shelley’s gradual recollection of his past memories allowed Guice to draw settings and characters not seen in typical DC Comics, and he enjoyed the opportunity to flex his creative muscles and demonstrate his full range as an artist.

“Resurrection Man was [Dan Abnett’s and my] first ongoing book at DC and we were so fortunate to have Butch as our artist,” Lanning said. “The success of that book was in no small way due to his amazing art – the blend of realism and superhero dynamics helped to give the series its unique voice. We never really go to work together much after the series ended but I always followed any title Butch drew because I knew it would have quality art and storytelling. I am forever grateful for the time we got to work together and for the page of original art that he generously gave me.”

Chris Sparks, who was a regular visitor to Guice’s Asheville studio while he was drawing Resurrection Man, said that the artist really enjoyed the series, and the challenges that came with illustrating a title that spanned several millennia.

“One of the best things about his art is his attention to detail. Short story, full issue, didn’t matter, he’d put so much care and detail into each panel,” Sparks said. “I’ve never witnessed an artist who can do that the way that he did. He continued to grow from book to book, Micronauts to X-Factor to Flash to Action to Resurrection Man, he was always challenging himself to do better. Every project he pushed himself to do his best work. He never phoned it in.”

Though critically acclaimed, Resurrection Man was never a top-selling title for DC, and the series wrapped up after a respectable 28-issue run. Guice immediately found more work at DC, joining writer Chuck Dixon on Birds of Prey. “In November of the year 2000, it was 3 p.m. on one of those regular Wednesdays at DC Comics, when the Editorial Department sat in an hour-long meeting led by Executive Editor Mike Carlin,” said Joseph Illidge, Guice’s editor on Birds of Prey. “When your book was called, you had to speak up and tell the detailed status in relation to the printing schedule for timely production. Way ahead of schedule? On time? Late? God have mercy on you if your book was running late.

“Birds of Prey #15, the first issue of the new year, first issue of my true editorial vision for the series, and first issue with new penciller Butch Guice was called. It was not ‘way ahead of schedule’ at all. Butch had just finished his duties on another book for editor Joey Cavalieri, so we were off to a slightly-behind-schedule start.

“He received the whole package of materials I sent him: script, character reference, Batman universe bible, and a thick stack of Bristol board upon which to work his magic. Before he started the issue, we had a talk on the phone, and Butch said something to me that I didn’t see coming from someone of his artistic skill and tenure in comics.

“He wasn’t sure how to follow after the series founding artist Greg Land. Greg’s art style, which was one part glamour, one part photorealism, and one part dynamism, had become indelible in the minds of the dedicated Birds of Prey fans. ... There was no doubt in my mind that Butch was the right artist for the job, but we both looked [nervous] about the task.

“I told Butch to think about Birds of Prey like an apartment,” Illidge said. “Greg Land lived in the apartment before you, and made it his home for a while. Now he’s moved out, and you’re entering the empty place. Bare walls, nothing anywhere, broom-swept floors. You’re going to clean it, bring in some new furniture, put up some curtains, paint the walls, hang up some art, and one day before you know it … it will be your home. Birds of Prey is yours now, for as long as you’re here. Have fun with it.

“Two weeks later, the first pages started coming in, and Butch began his journey on one of the most beloved runs of the series across different volumes, and the franchise in general. Issue #15 was completed on schedule, as was every issue Butch and I worked on together after that. Butch was respectful enough of the artist who came before him to recognize the impact and the responsibility of carrying the baton afterwards, and he was humble enough to have already drawn some of the most popular characters at The Big Two publishers and yet realize that Birds of Prey was a unique kind of responsibility beyond The Man of Steel and Marvel’s uncanny mutants.

“He was smart enough to consult his wife Julie when it came to hairstyles and fashion sense for the series’ lead characters, Dinah Lance and Barbara Gordon. He was humane enough to show us the different sides of humanity in his art with equal application of truth and care. He was gentlemanly enough to always appreciate the opportunity to speak to the world through his art. He was kind enough to be a friend to a fan-turned-caretaker. That’s the guy comics gained. The guy we’ve all lost. A great artist and an old soul, flying through the heavens like a beautiful bird.”

Cover to Ruse #1.

Cover to Ruse #1.During his run on Birds of Prey, Guice was invited to join upstart publisher CrossGen, which provided healthcare and employee benefits to its editorial and creative teams provided they relocated to work regular office hours out of its headquarters in Oldsmar, Florida, just outside of Tampa.

“I met and got to work with Butch during the CrossGen days,” said Mark Waid, who served as one of the publisher’s creative directors. “All the artists there, working in cubicles in a giant bullpen, were required to post copies of all the work they'd done that day, the idea being that a friendly sense of competition would raise everyone's bar. Without fail, Butch's pages were the ones that got the most internal praise and attention, and deservedly so.

“He was a friendly man as well as a talented one; we spent many lunches talking out stories for our series, Ruse, and he was a generous and smart contributor with no real ego about it. He loved to draw. In fact, he loved to draw so much that whenever I gave him a plot for a Ruse issue, he'd draw twice as many panels as I'd called for, so half my time was spent trying to figure out what the hell the characters could be saying, which is why that book is so verbose. But the end result was always better than either of us could have done with a different partner.”

Ruse, a Victorian-era detective serial, drew critical acclaim and proved to be one of CrossGen’s most successful titles, earning five Eisner nominations, with Laura Martin winning for Best Coloring. Inker Mike Perkins was on board with Ruse from the beginning, having lobbied for the book when he heard that Guice was joining CrossGen.

“I was a follower of his work from just before he created X-Factor and I continued to follow his name around wherever he lay his hat,” says Perkins. “I was always assured of quality. Great figurework, dynamic realism, comic book brilliance. When I was asked to work at CrossGen, I was originally brought in to ink another marvelous artist but then I heard that Butch had been recruited and I fought for the chance to collaborate with him instead as I felt our approach to illustration hit the same base points. I don't regret a single day, even when Butch left the company. ... 'Don’t ink my pencils. Ink my intent,’ is what he told me, and I did my best to follow that advice."

“Soon after, we shared studio space in Safety Harbor alongside Laura Martin and Drew Hennessy for another three years and we continued to relish each other's company. Joking. laughing, curmudgeoning, putting the world to rights and helping each other out. Oh, and working together ... even when we weren't meant to be doing so.

"He adored the Thin Man movies, Steed and Mrs. Peel, and this was reflected in the work we produced together on Ruse. He was fascinated with WW2 history and kept a picture of the young Queen Elizabeth II on his wall. His direct influences, and constant inspiration, came from the newspaper strips of Terry and The Pirates and Noel Sickles. An old soul but, if reincarnation should have a place in this universe, perhaps it's a soul that I'll be lucky enough to encounter again."

“Despite him being an old soul, I could tell he loved his youth. A childhood of adventures in the woods. A playground of imagination. He never left that playground, really.”

A two-page spread from Olympus.

A two-page spread from Olympus.As with Resurrection Man, Ruse saw Guice take his work to the next level, and to demonstrate his incredible range as an artist. “To this day, I think he’s one of the most underappreciated artists of our generation,” says Chris Sparks. “But Ruse is when people finally took notice and got a sense of just how talented he was.”

Guice left CrossGen just prior to the company’s mass layoffs and eventual closure, and once again had no trouble finding work when he resumed his freelance career. His first major project was the graphic novel Olympus, written by Geoff Johns and Kris Grimminger and published by Humanoids. "I've been interested in working with Paul Benjamin and Humanoids for several years now... [their] approach to their material, both in quality and design of product, as well as the extensive worldwide market they've cultivated with a variety of genres, held enormous interest for me,” Guice said in a 2004 Newsarama interview. “After my resignation from the CrossGen staff, I contacted Paul and we started talking about possibilities. Once I read the two scripts for Olympus, I knew it was exactly the type of thing I would enjoy drawing. Having it be written by Geoff and Kris was a very pleasurable bonus.”

In 2006, Guice teamed with writer Warren Ellis on the JLA Classified story arc "New Maps of Hell," followed by Aquaman: Sword of Atlantis, part of DC’s “One Year Later” storyline, in which every ongoing DC Comics title experienced a one-year narrative jump in the aftermath of the Infinite Crisis crossover. The series centered on a new Aquaman finding his place in the undersea kingdom as the fate of the original King of the Seven Seas remained shrouded in mystery.

“I only met Butch a few times at conventions, and while we were working on Aquaman, we only did email and an occasional phone call,” recalled Kurt Busiek. “We talked about our mutual admiration for Terry and the Pirates, and I told him I'd try to get some of that adventure feel into Aquaman. He did say that what he enjoyed a lot about the Aquaman run was that we didn't have any cities in it, mostly just natural environments, and those were much more fun to draw. He said that any time he didn't have to use a ruler or reference a car, he was happier.”

Following his stint at DC, Guice was invited to join colleagues Steve Epting and Mike Perkins at Marvel on Captain America, which had become a high-profile title again under writer Ed Brubaker, who garnered headlines by resurrecting Cap’s long-deceased sidekick Bucky Barnes as the deadly assassin known as The Winter Solider. Epting’s detail-oriented, realistic artwork set the tone for the series, and Guice made for a seamless addition to the creative rotation.

“Butch was one of the best craftsmen working in the field and a lot of fun to work with,” said Brubaker. “He had the skills of a classic era comics artist like John Buscema or Jim Steranko, and I think some of the work we did together, especially his double-page spreads on Captain America, rank with the best of the best. An underrated talent his entire career, who was always happy to be drawing comics anyway. I will miss him.”

Page from the first issue of Winter Soldier.

Page from the first issue of Winter Soldier.Guice served as the primary artist on Brubaker’s Winter Soldier spinoff series, and enjoyed a successful return to Marvel as he illustrated single issues, specials, short-story arcs, and the occasional ongoing series, including a modern-day relaunch of The Invaders, a World War II-era superhero team created by Roy Thomas and Sal Buscema in the late 1960s.

“Like everyone, I was a huge fan of his work. His relaunch of The Flash back in ‘87 is seared into my brain, filled with the kind of energy and power you can only find in comics while still feeling so incredibly real,” said Invaders writer Chip Zdarsky, via his newsletter. “A consummate draftsman who inherited the mantle of a style originated by greats like Alex Raymond and Al Williamson, Butch was their equal, the artist you went to when you needed to feel like these characters actually existed, actually had real, genuine emotions.”

Throughout his career, no matter how many accomplishments and accolade he received or how many best-selling titles he illustrated, Guice never forgot his roots as a small-town kid drawing fanzines and taking every gig that came his way.

“I was lucky to do some shows with him over the years, including his last time at San Diego, in 2015, when he won the Inkpot Award,” Sparks said. “And watching him with his fans, he was always so generous with his advice. He’d spend a lot of time with artists going over their work and talking shop, helping however he could. You don’t always see that with artists.”

One artist that Guice mentored, Shannon “S.L.” Gallant, can attest to Guice’s kindness and generosity toward younger artists.

“I can’t say I was close to Butch, but he was an incredibly important part of my own life. When I was in high school, other guys had swimsuit models in their locker, but I had images that Butch had drawn, and that isn’t an exaggeration,” Gallant said. “When Chris Sparks introduced me to him at HeroesCon, and Butch allowed me to hang out with him for an evening, I was like a kid meeting Santa Claus. In the years that followed, Butch was kind enough to correspond with me, and would pass along copies of pages he was working on. After getting an email from him, I wouldn’t shut up about it to my wife. I’d talk about why I admired his art so much, to the point that after I bought a batch of pages he had done, when she saw them, she was able to tell me, ‘You bought this page for that background, this one for that headshot, this one for those guys in the suits.’ She was spot on.

“Every page he would send was a master class in all aspects of comic art, from panel composition, page design, storytelling, figure work, down to drapery. My wife could always tell when I had gotten an email from him, saying, ‘You’re in a good mood. You must have gotten an email from Butch,’ which I usually had. Other artists have similar stories, and the lucky ones have even stronger memories, but I’m thankful for the ones I do. He was a great talent, and I will miss that excitement of a kid on Christmas morning I’d get when seeing an email from him.”

Over the past five years, Guice became more selective with his projects, preferring to concentrate on commissioned illustrations and the occasional one-off or mini-series, or sharing his knowledge and appreciation of classic comic strips with friends and fans on social media.

“Butch Guice was more than a phenomenal artist. He was one of those rare creators who could put differences aside and work with anyone who treated him with respect and gave him something to draw he could sink his teeth into,” said longtime friend and collaborator Greg Wright. “And you might never know what it would be that he'd be really jazzed to draw. And fans might not know that he was really funny. Bitingly so. He and I worked on a couple of funny stories and his ability to do visual humor was spot on. For all his talent, my favorite thing to do with him was just talk. Comics, art, whatever. He thought deep. Appreciated everyone's work more than his own. Everyone who knew him will miss him dearly.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·