Henry Chamberlain | June 5, 2025

This is the story of Taha Siddiqui, a journalist-in-exile who survived a kidnapping and assassination attempt, and went on in 2020 to found The Dissident Club, a bar and literary cafe in Paris that embraces dissidents from around the world. How Siddiqui went from a strict Muslim fundamentalist upbringing to becoming an outspoken journalist is what informs this memoir. Immediately, I think of any number of graphic narratives, from Persepolis to Blankets, with a protagonist confronting the limitations of a strict religious authority and their need for self-autonomy. What strikes me right away about Siddiqui’s approach is its even-handed and steady pace.

No birthday parties.

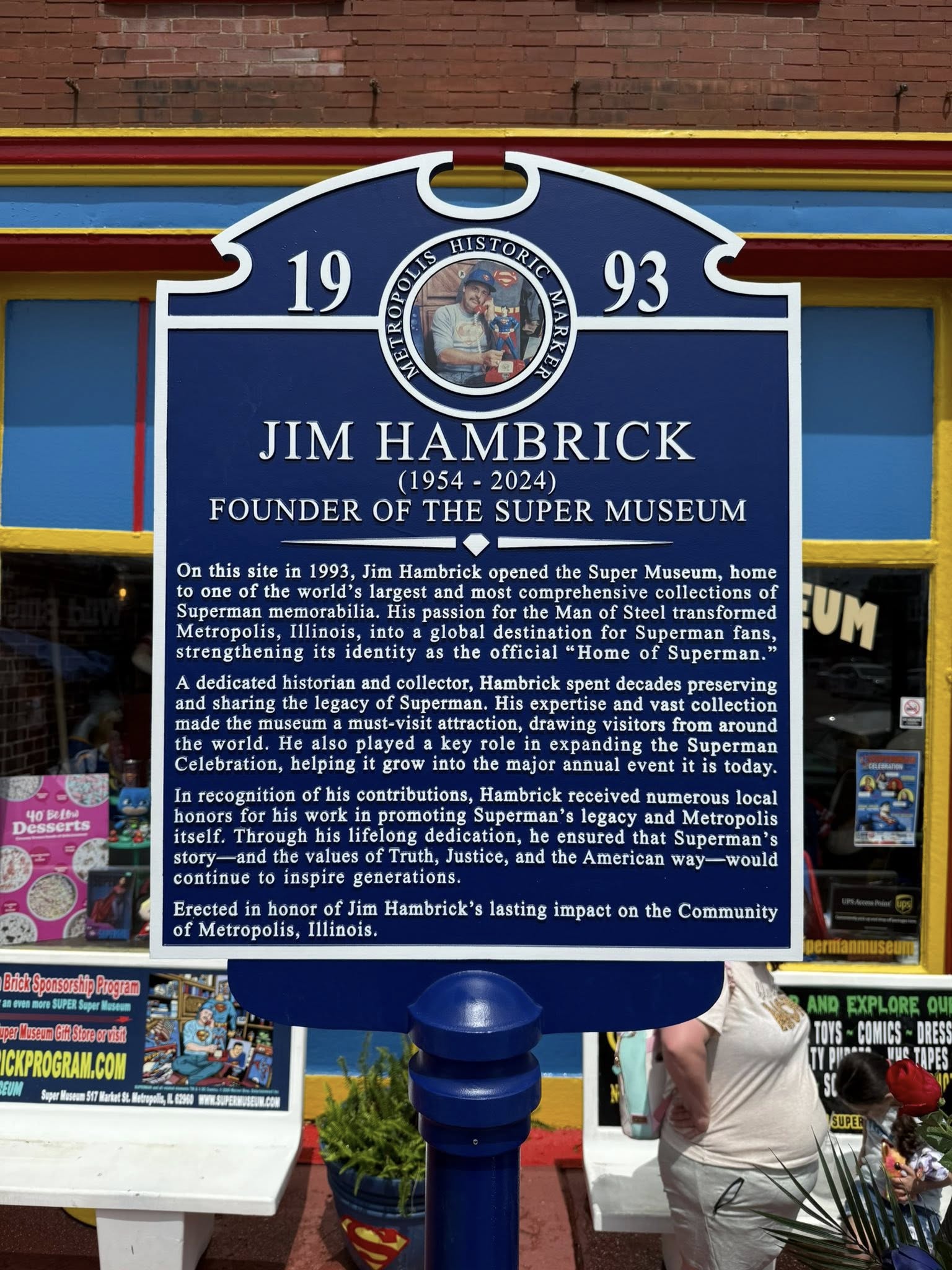

No birthday parties.Siddiqui chose to tell his story in a very meticulous chronological order, starting with his growing up in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan in the 1990s. Thankfully, he does alternate, from time to time, with some present-day narration that did wonders for my reading as I assessed the author’s point of view. Interestingly enough, Siddiqui adopts an initially kind-hearted and tolerant tone in depicting his father’s ever-increasing religious demands upon his family. No, the children must not call him, “Papa,” since that is Western; they must call him, “Baba,” as in any good Muslim family. No, the children must stop reading comic books, watching TV or any movies. And no birthday parties, as it would insult Allah to be so selfish. Siddiqui chalks this up as simply having to mind his parents but the steady drip of restrictions eventually becomes too much. Taha and his friends don’t dare play soccer and miss a call to prayers in fear of being scooped up by the Muttawa, “the religious Pakistani police,” and getting tortured.

It is not obvious all at once, but that steady drip, drip, drip of one religious edict after another leads Siddiqui to see reality: his father joins a jihadi mosque; and his neighborhood harbors a compound owned by Osama bin Laden. It is this intimate experience that leads Siddiqui to his future endeavors as a journalist, confronting corruption and abuse. By 2000, Siddiqui’s family is in Pakistan, and he is completing high school. At the time, Pakistan appears to be in relatively stable hands after a military coup. It will be only a few years later that this same military government will attempt to kill him.

It would be an understatement to say that Siddiqui’s story must be told. Just the other day, I was in a conversation with a colleague who doubted just how efficient comics are at storytelling. I didn’t put a fine point on my disagreement because it wasn’t the time nor the place for it. But I will say here what I’ve said before: comics have a built-in mechanism to tell stories with great efficiency, from the medium's unique ability to be concise to its compelling use of words and pictures. That said, this graphic memoir is on a particular mission, and it succeeds. Siddiqui lays it all out: his upbringing; his rise as a journalist; and his ultimate experience in the never-ending fight of calling out truth to power. The story is not fancy; it leans more towards sticking to the facts. For the most part, you have your key players as if on a minimal stage, reciting their lines.

The artwork by Hubert Maury is very practical and plays its role quite well. It is not distracting while imbued with a subtle charm. What I appreciate about Maury’s art is that it adds another track of storytelling that seamlessly compliments Siddiqui’s narrative and keeps to the goal of being clear and concise. For example, Maury adds a wonderful emotional layer with his masterful facial expressions and body language. This is crucial in better appreciating the gray areas to the relationship between Siddiqui and his father. Even when his father is at his wit’s end and quite angry, I never lost sight, in part due to Maury’s depictions of him, of his humanity and vulnerability. In the end, it all adds up to a powerful, and efficient, narrative.

Taha is Sunni, and Sonya is Shiite, right out of Romeo and Juliet.

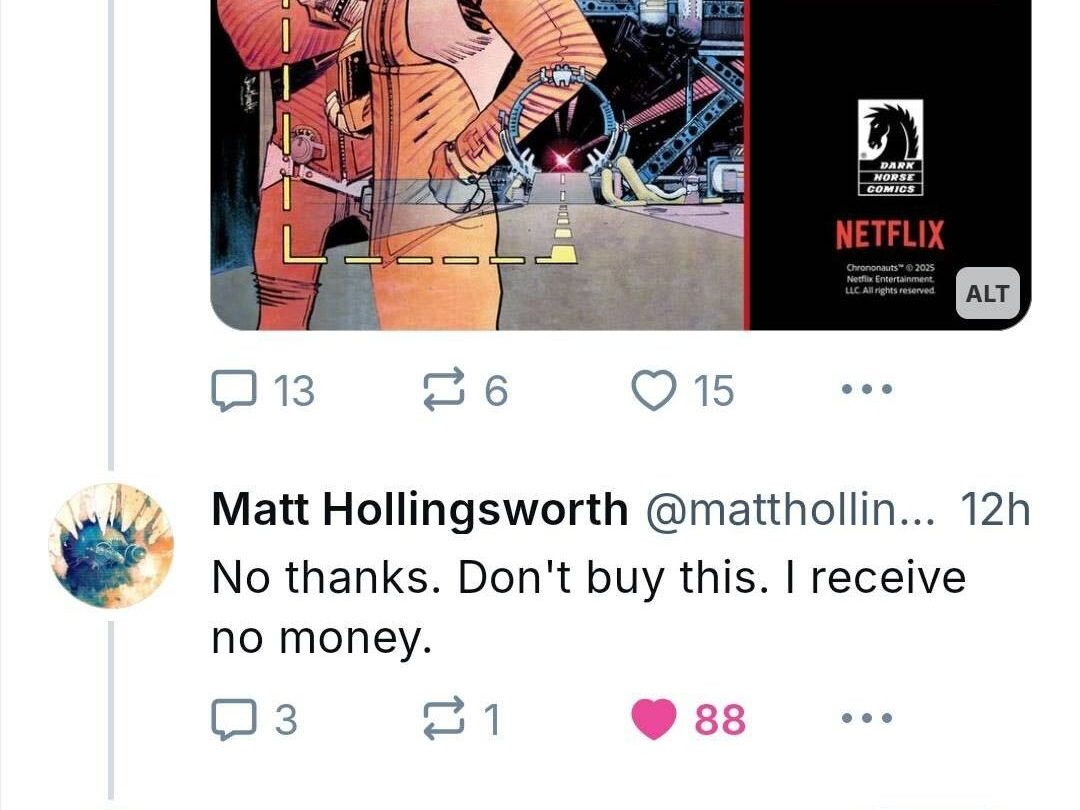

Taha is Sunni, and Sonya is Shiite, right out of Romeo and Juliet.Another essential aspect to this book is the translation by David Homel. Homel has translated some of my favorite graphic narratives: Saigon Calling, Such a Lovely Little War and Swimming in Darkness, titles that share the same publisher, Arsenal Pulp, as this book. I am always delighted by Homel’s work. His natural grace does not go unnoticed. Each of these titles was originally published in French and I can imagine that Homel took great care in preserving each title's unique flavor. The style and vernacular attached to this book is very smooth without a stilted passage to be found. And, as to comparisons to Persepolis or Blankets, I think the natural and authentic narrative, in the script, translation and artwork, all add up and this book holds its own in such esteemed company. There’s even a romantic subplot that will melt any reader’s heart.

Despite their troubled relationship, Siddiqui paints a balanced portrait of his father. They may not agree on anything, but father and son do not outright hate each other. The senior Siddiqui pays his son’s college tuition and supports him in every way possible but also does everything in his power to keep his son from being a journalist, including storming into the offices of his son’s employer to protest. But even that didn’t stop Siddiqui from being able to depict his father with humanity. By the same token, even when his own son did everything to thwart his plans for him, the senior Siddiqui managed to relax his rage and, going against his better judgement, allowed his son to finally slip through his fingers and have his own life.

It would be an understatement to say it takes courage to stand up and report on oppression. Siddiqui would be the first to say he is not alone in this fight. As Siddiqui shares his progress as a journalist, I am moved by his ability to maintain proper perspective. He makes a point of honoring his fellow activist-journalists like Sabeen Mahmud, Julien Fouchet and Hamid Mir. Siddiqui, and his colleagues, repeatedly reported on Pakistan harboring terrorists. According to Siddiqui, that will get you on a government hit list: Mahmud was murdered; Mir was nearly murdered; Fouchet was exiled; and Siddiqui was kidnapped and nearly murdered. His current life in Paris, operating a bar and haven for fellow dissidents, offers a fitting end to the story.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·