Animal Pound HC

Animal Pound HC

Writer: Tom King

Artist: Peter Gross

Colorist: Tamra Bonvillain

Letterer: Clayton Cowles

Publisher: Boom! Studios

Publication Date: April 2025

George Orwell’s legacy might be cursed. In the 75 years since his death, his work has constantly been appropriated and misunderstood by political forces who want to cash in on his influence and audience but sand away all the rough edges of his life and perspective. From the CIA’s interest in Animal Farm, to Silicon Valley’s repeated evocation of Nineteen Eighty-Four, you’re left to wonder if we should perhaps throw the baby out with the bath water.

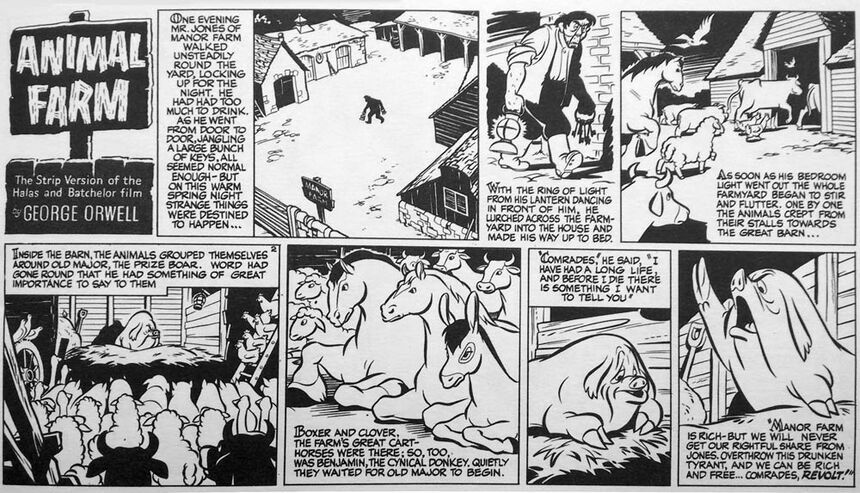

In Orwell’s Animal Farm, farm animals rally behind the prospect of a better world based on the teachings of Old Major, uniting to revolt against their oppressors at the Manor Farm, run by Mr. Jones. After which they have to contend with the political realities of revolution and the nature of power to corrupt even the best of intentions. Orwell’s thinly veiled allegory features several one-to-one parallels with Communism and the history of the Soviet Union, from the Marxist-Leninist Old Major/Trotskyist Snowball/Stalinst Napoleon, all the way to the Pigs’ appropriation of milk as a metaphor for the Kronstadt revolt. In fact, Orwell’s original is so layered in these connections that you would be hard-pressed to find any detail that isn’t in some way or another a reference to the history of the Bolshevik revolution and the Soviet Union’s eventual ideological and material decline under Stalin.

Due to how explicit these connections are, Orwell had a hard time finding a publisher who would take on the risk of releasing the book. As it was written, World War II was still in its final days and the USSR was considered an ally by America and Britain. As such, there was presumed to be no audience for the novella, politically inclined or otherwise. His own former publisher, Victor Gollancz said he “could not possibly publish a general attack of this nature.” When it was finally released in 1945, and following Orwell’s death in 1950, the political landscape had significantly changed. Suddenly the tragic folktale of the allure and decline of socialist principles in Russia turned into an easily distributable pamphlet that the CIA and other intelligence agencies could use to stoke anti-communist sentiment across Europe.

For example, in 1950 the British Information Research Department (IRD) commissioned a comic-strip version of Animal Farm by Norman Pett and Don Freeman that was subsequently distributed throughout Britain’s sphere of influence. The US Army contacted Orwell’s estate to gain the film rights for Animal Farm, eventually leading to the CIA financing and heavily influencing the 1954 animated film. This film was itself adapted into another propagandistic comic strip in 1954 by Harold Whitaker, an animator on the film. Orwell’s books were also heavily distributed and ingrained into the culture of European countries to discourage the possibility of allying with the Soviet Union, with Animal Farm being particularly popular in the West German school curriculum.

Today we must contend with the legacy of these actions. Is Orwell worth reading or was he just a tool in a government psyop? Has his name become too poisoned to take seriously? And is it worth parsing out the appropriated legacy from the work’s own context? These are difficult questions to answer, but one thing is for sure: Tom King writing Animal Pound makes the task that much harder.

Animal Pound — by Tom King, Peter Gross, Tamra Bonvillain, and Clayton Cowles — is a reimagining of George Orwell’s Animal Farm that relocates the story to a present day American pound. The series follows three central characters: Madam Fifi, the Good Boy Titan, and the unruly Piggy as the three liberate Manfield Pound in the name of freedom, and then wrestle with how to justly organize the cats, dogs and rabbits that all still have to live there.

Whereas Animal Farm was a fairly direct allegory, Animal Pound takes the route of a cautionary tale. The series is an amalgamation of various political ideas depicted with the iconography of Orwell rather than directly parallelling a series of watershed historical events. There are many allusions and references throughout, but nothing is quite one-to-one in the style of Animal Farm.

That choice regrettably puts Animal Pound in the same category as most, if not all, adaptations of Orwell. Animal Pound’s inability to substitute a sharp historical and political view with anything but a familiar aesthetic renders this cautionary tale inert and ideologically confused, in a way that specifically highlights the flaw in most of King’s political comics from Sheriff of Babylon and The Omega Men all the way to Strange Adventures. Peter Gross and Tamra Bonvillain do their part to create instantly recognizable (and adorable) animals, which is a commendable feat, but it’s all in service to a script that thinks it’s saying far more than it actually is.

Animal Pound’s core misstep is in being more aligned with the cultural impression of Orwell rather than George Orwell himself, and as such its “Orwellian” elements are not tangible, material aspects of a wider political perspective, but rather follows the trend of the brazen fear mongering that was employed by governments to popularize Orwell post-World War II. This seems unavoidable as Tom King, a former CIA officer himself, is well aware of the agency’s part in Orwell’s legacy and still calls them “my people,” without ever using the comic to interrogate the implications of that connection. While Animal Pound resists being propaganda in the same vein as the 1954 animated film, at the very least that unambiguous intention would give us something more complex to unpack and discuss. Instead, King’s work is largely abstract, gesturing as classical problems of freedom in liberal political theory and merging the concept of Animal Farm with the notable elements of Trump’s MAGA movement without ever saying very much or reflecting on the medium, the history of Orwell’s story, or even the real world politics it claims to care about.

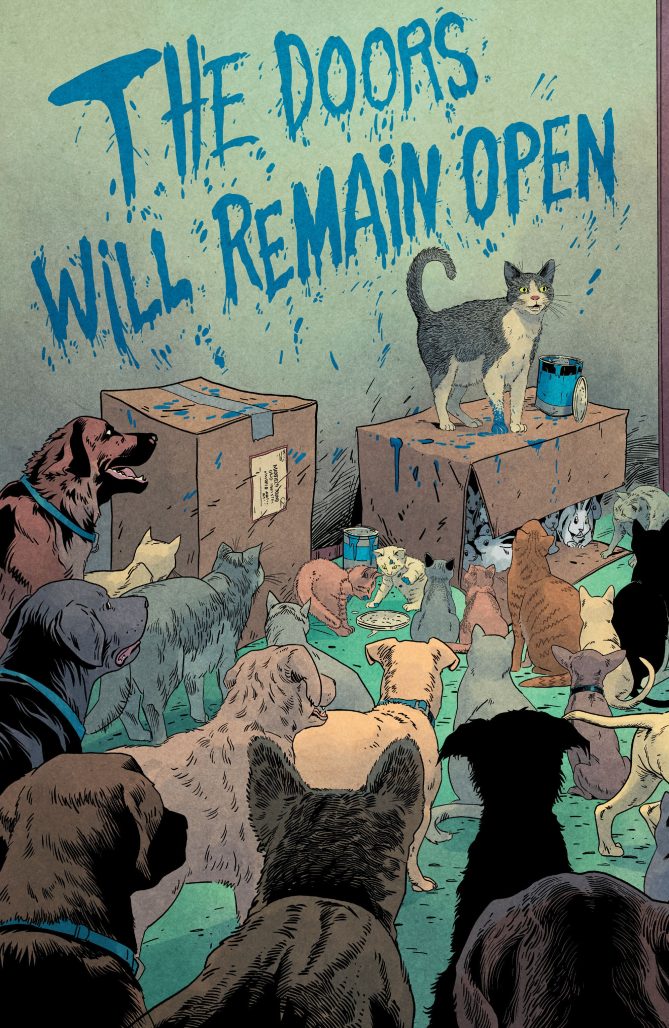

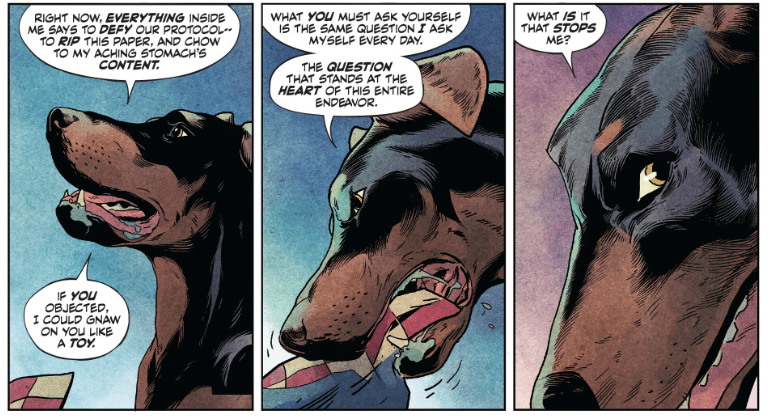

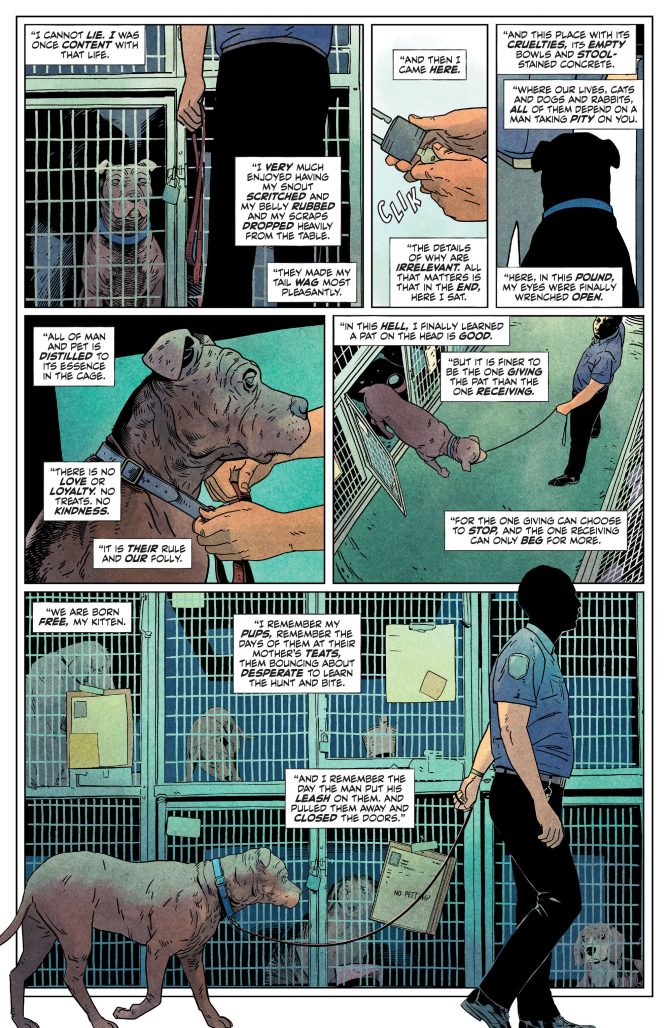

Animal Pound sets up its central conflict well by having Fifi in the first issue claim freedom demands nothing, the implications of which form the bedrock of the entire series. Lucky (the replacement for Old Major) opens the series by articulating the lack of freedom experienced by dogs, how their entire life from birth to death is dictated by the hand that feeds them. He explains “The doors you see, the doors. That is our burden. That is man’s true gift to us. Doors to contain us, doors to separate us, doors to control us. We spend our entire lifetime staring at the door, scratching at the door, howling at the door. Pathetically praying for someone to please, please open it for us.” Thus an end to the doors, the unlocking of cages and the freedom they represent, is the ultimate dream of the animals, a dream that is ill equipped to contend with the reality of real governance.

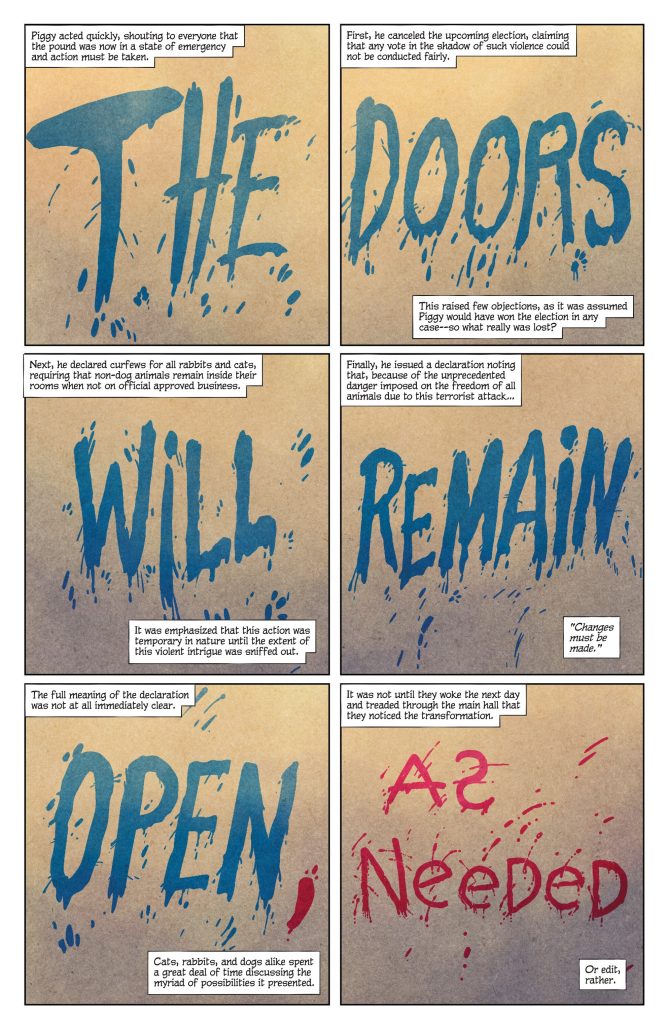

This concept of the door as a device for freedom becomes so central that King replaces Orwell’s Seven Commandments of Animalism with one simple principle.

After the successful revolt against the pound workers, Fifi and Titan see very quickly that freedom does indeed have demands, and that the lack of control they previously experienced hid that cost from them. The animals realize the dogs can eat the rabbits, and the cats outnumber the dogs, all the while there is no money for food. The masters are gone, but what stops the animals from devolving into a State of Nature on their own and retroactively admitting the need for someone to control them? Titan asks this very question to Fifi, for which she does not have an immediate answer.

King here isn’t paralleling American history in the way Orwell was paralleling Soviet history. We are not moving from the American Revolution to the war of 1812, all the way down the line of America’s life. Instead, he’s reiterating the philosophical problems of freedom that were discussed and addressed in early American political theory. If America was founded in conversation with the likes of John Locke, Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, then King here is distilling those core conversations down to questions of how one escapes the State of Nature, why freedom on its own terms is valuable, the existence of a good Will, and how the institution of representational democracy can address competing needs.

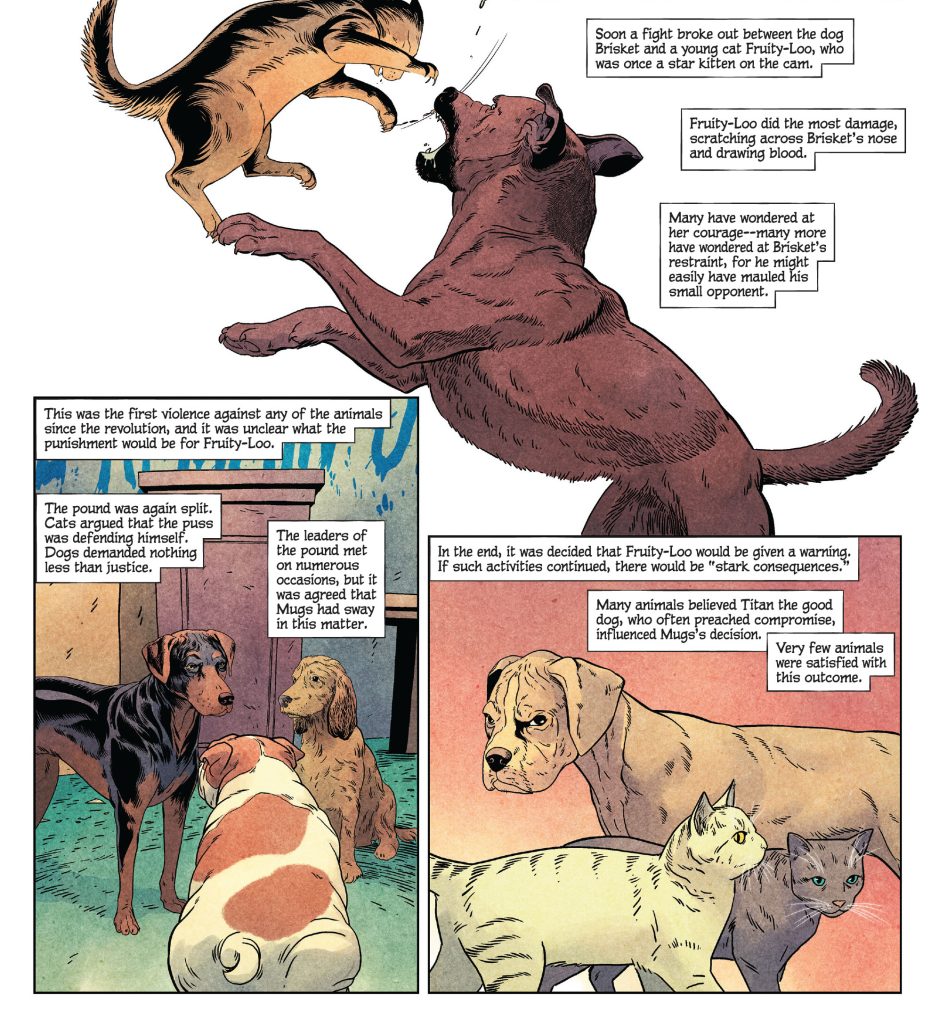

The conflict of dogs, cats and rabbits is ultimately one of positive liberty vs negative liberty. The rabbits, for example, are seeking negative liberty or freedom from being consumed by the dogs. Meanwhile, the dogs are seeking positive liberty or the freedom to do whatever they want, namely eat the rabbits. The cats are in the center, with a desire for both negative liberty that would protect them from the dogs and positive liberty that would let them go about their days of lazily napping and roaming the grounds. The problems of lack of food and lack of government introduce the question of what barriers stop the dogs from simply acting in the interest of their positive liberty? Even if there were rules, laws and a government, what reason does one have to obey them aside from just being a good person animal to begin with? And is a system that cannot enforce such behavior one that has the ability to survive? As the series progresses, we see this problem manifest when cats and dogs come to blows but the representational democracy in place cannot come to any consensus on punishment for those that break the rules.

Ultimately, like Orwell’s original, these problems continue until the system itself collapses, for nothing united any of the animals in achieving their dream aside from the dream itself. With no protections, no shared interests and no way of enforcing a set of protections or interests, the cats, dogs and rabbits merely traded out one prison for another.

Gross and Bonvillain are essential here for representing the struggle of freedom through the paneling. The opening pages of Animal Pound are in imposing grids, not just copious symmetrical panels but literal bars and cages inside the already prison-like panels. This choice feels appropriately oppressive and even tedious. As I discussed in Helen of Wyndhorn, King’s scripting has evolved to be more novelistic and so we spend far more time on every page. Spending several minutes reading while looking at these sad, imprisoned animals truly weighs on you, and I couldn’t help but feel sympathy for Fifi’s misguided but understandable assertion that freedom demands nothing, for what demand could ever equal the depressing material conditions of the pound?

These pages are compounded over the course of the whole series, moving from prisons of a literal kind to the prisons of political gridlock that make up the comic’s ongoing drama. Over and over, you read about the idea of freedom, about the promise of a better world but over and over all you see is stagnation, and the repetitive motions of political maneuvering that makes you wonder if life was perhaps better before. Either way, a prison is a prison.

This is until the final issue, when we get a beautiful 2-page spread, depicting the promise of freedom that would have made all the risk of revolution worth it. The open field and the concept of animal liberation doesn’t just open up life for the characters, but it opens up life for the reader as they finally get to move their eyes and see a whole image rather than being systematically forced into small boxes stacked on top of each other. It is a truly wonderful effect, and one that takes patience to pay off.

But this page is bittersweet, coming after established democracy has already been usurped. We get a glimpse at the promise of freedom in a manner that enriches the suffering, as a reminder that this is not only what we fought for but what we lost. One is also left to wonder, with the fence still prominently in the background drawing the reader from Fifi to Titan across the page, if freedom itself might have been an illusion? There is no true, perfectly open space, just bars and cages that are further away.

King famously states in The Omega Men that the 9 panel grid represented “bars on a cage,” separating fiction from reality in a way that was unnatural, unaware of the impact the two have on each other. His career in comics has been defined by probalitizing that separation from Omega Men to Mr. Miracle to Rorschach and most recently Helen of Wyndhorn. Clearly the real always pushes and pulls on the unreal, and it’s simply a question of what we allow ourselves to see as fiction vs reality. Thus, Animal Pound’s collapse of its political project isn’t just a cautionary tale, but one that enforces King’s usual concern of the connection between the comic’s ideals and our own. In King’s own words, Animal Pound originated as he witnessed the January 6th Insurrection:

“This is people trying to take advantage of a system that is working, and take the flaws in the system — that are built into the system — take advantage of those flaws to overthrow democracy.

I wanted to write something that addresses that problem — a problem of today and the problem that we’re facing now — and to use the tools that Orwell used: the idea of using animals as allegories.”

-Tom King, Screen Rant, 11/10/23

In my opinion, this statement is worth interrogating in relation to Orwell’s own origins for Animal Farm, which was rooted in the betrayal of the socialist project. Following his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, Orwell was disillusioned by Stalin’s regime and political practices. Animal Farm wasn’t anti-communist so much as it was anti-Stalin (as Orwell explained to Victor Gollancz when he attempted to publish the book). This is often a point of contention with interpretations of Animal Farm and of Orwell’s wider views, as well as the victim of flatout distortions by some trying to appropriate his work for their own ends. Daniel J. Leab documents much of this in the early chapters of Orwell Subverted: The CIA and the Filming of Animal Farm:

“A good example is C. M. Woodhouse’s introduction to a 1956 American paperback edition of Animal Farm. Woodhouse praises Orwell for his political insights and acumen and quotes one of Orwell’s more famous essays (“Why I Write”): ‘Every line I have written since 1936 has been against totalitarianism.’ As John Rodden points out, however, Woodhouse leaves off the end of the sentence, which continues, ‘and for democratic socialism.’ …His shortening of Orwell’s sentence is an act of deception and distortion designed to adapt Orwell’s book to a particular point of view.”

As historian Ben Pimlott notes under no uncertain terms, “Orwell was a socialist… for there are many who have preferred to ignore this fundamental aspect of his life and work.”

King ultimately has more in common with Woodhouse than Orwell, frequently using the phrase “totalitarianism,” whether it’s in relation to Rorschach or Animal Pound, but rarely providing a solid counter view that isn’t merely gesturing at abstract American Ideals. He respects Orwell’s craft but never engages with what that craft was striving towards. His political works are of someone who wants to be political without defining their own politics. Thus, what can we really glean from Animal Pound other than an idealistic portrait of American principles and a cynical statement about their eventual consequences?

King’s treatment of Orwell’s source material betrays a common weakness in fiction of this style. No allegory or cautionary tale, whether it uses one-to-one comparisons or not, can escape questions about whether the allegory itself appropriately captures its target and subject. Orwell picked a farm because farms are a mode of production. The animals are laboring, and they are arguing about what their labor is in service to and who reaps the benefit of it, all as a thinly veiled parallel to the actual agricultural workers of Russia. But what is a pound in relation to King’s vision of America? The abstract notions of positive and negative liberty can be applied just about anywhere, even his metaphor of doors isn’t new in articulating this issue, so what is his idea of the Pound adding?

The animals here do labor, but they labor as internet celebrities, clowning on a camera to earn money. This is surely a concept meant to poke at reality-star-turned-president Donald Trump, but how is this device criticized or paralleled to real world issues of the internet in a border sense? This cannot be a criticism of America’s founding and its economic capital, and it’s surely not a criticism of the present moment of tech oligarchy since the webcam is just how the pound pays its bills. It’s a choice that exists to arrive at the Trump parallel, but it’s not one that makes coherent narrative sense in the wider allegory of the series.

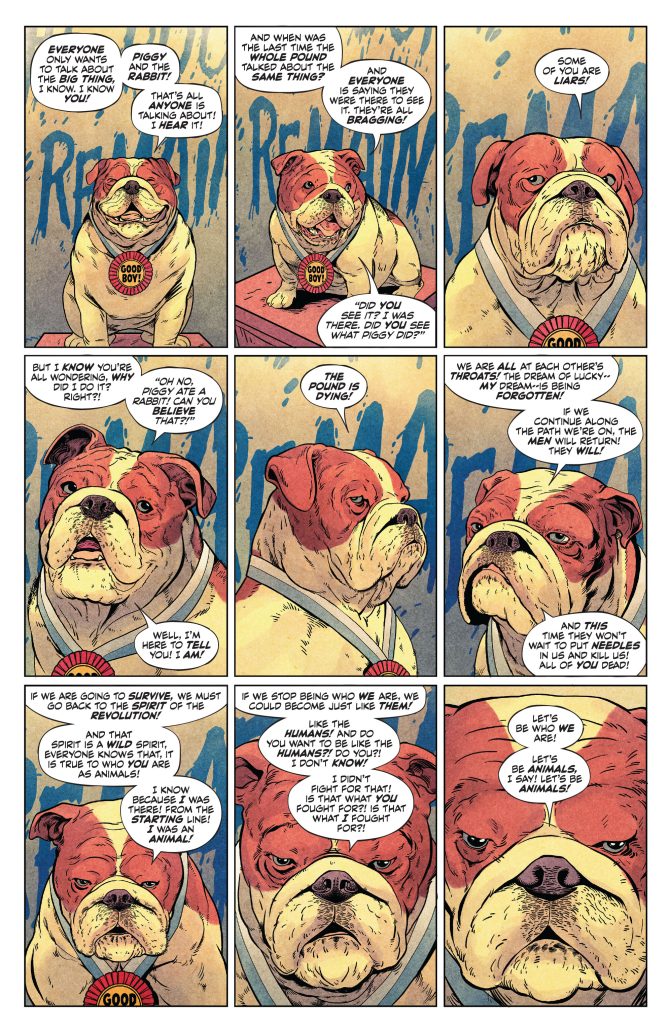

Piggy, the last justly elected leader of the pound and the one who ushers in the end of democracy, is in no uncertain terms an allegory for Trump down to his slogan and red hat. His name is a call back to the class of Pigs in Animal Farm who betray the spirit of the revolution and become indistinguishable from the capitalists the animals sought to escape. The most interesting thing about Animal Pound to me is Piggy and King’s own point about the “flaws… that are built into the system.” Piggy was present at the start of the revolution, cowardly waiting in the wings and letting Fifi and Titan carry on without him. After the successful liberation of the Pound, Piggy takes credit for being a hero present since the start of this endeavor. His lies about his actual participation rarely come up but in the early days of Animal Pound we feel like everyone already knows Piggy’s boasting is merely just that. As the series goes on, and the animals’ immediate needs outweigh their long term memory, Piggy is able to take advantage of the discontent of the animals and gain power. Following this, he breaks the established traditions of two terms as leader and undoes the work of the past leaders, ushering in an age of his dictatorship under the slogan “Let’s be animals again.”

King is paralleling quite a few things here but he’s saying very little. As we watch Trump today insist on a third term, as we watch past traditions and agencies gutted, as we hear constant lying from the oval office, Piggy is obviously a much clearer one-to-one than anything else in Animal Pound. So much so that Issue 5 even opens with a note that it was completed prior to the assassination attempt on Trump, an event that also occurs in the comic.

But these connections do not help the allegory come to any concrete conclusions or point of view that can be illuminating. King’s best choice is to plant Piggy in the first issue, as a way to insist that the flaws of the system are there from the start. But one is left to wonder: if the flaws are there from the start, if they can always be exploited, then was this not inevitable?

In Orwell’s Animal Farm, the liberated animals draw up the Seven Commandments of Animalism:

- Whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy.

- Whatever goes upon four legs, or has wings, is a friend.

- No animal shall wear clothes.

- No animal shall sleep in a bed.

- No animal shall drink alcohol.

- No animal shall kill any other animal.

- All animals are equal.

These are not just principles to live by, but also laws, the two working together to create a picture of a just society in the eyes of the animals. As the story goes on and as the Pigs take control, these laws are constantly modified, adding amendments and exceptions that the animals are gaslit into thinking always existed, all culminating in “All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others.” In contrast, Animal Pound has but one central principle/law: “The doors shall remain open.” The terror of Piggy is not merely that he’s rewriting the governing laws of animal society, but that he’s going back on the spirit with which this society was founded. He modifies this principle to “The doors shall remain open, as needed” ultimately as a symbol of what Piggy thinks of the democratic process, that those in power can circumvent tradition and no one can stop them because tradition is not law.

Once again, the paneling is exceptional here, taking the full page spread that originally introduced this mantra and replacing it with panels, a page that puts the animals back into cages spatially just as they are now spiritually, and soon will be literally.

This fatalistic approach to government that Piggy reveals to us is something that Animal Pound fails to properly interrogate. The observation that Piggy and his ilk, the people who would take advantage of the system’s intentional flaws have always been there, is a good starting point but it’s not a sufficient critique of the system. For if this can happen, what’s to stop it from always happening? King may want to argue here that the consequences of Piggy are a natural risk for any democracy, but democracy in spirit is better than not. But if fascism is at the core of democracy to begin with, is this not an indictment of the whole system? This is a conclusion which is consistent with King’s other political writings but not one that he properly investigates anywhere.

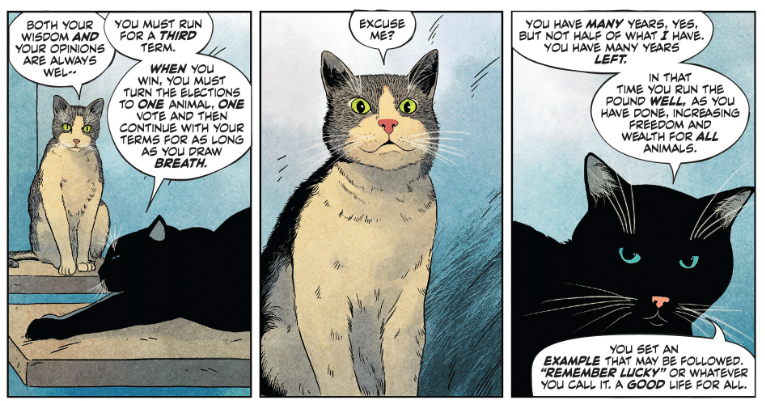

In issue #3, Raven asks Fifi quite directly to usurp democracy, for Raven understands that Piggy is inevitable and the only way to stop him is to beat him to the punch. Raven doesn’t hold any fondness for the revolutionary spirit or the government designed by the animals, but he pragmatically recognizes that the system is doomed to fail and it would be in everyone’s best interest, whether they like it or not, for Fifi to take control. The principled non-action of Fifi in this moment is contrasted with the opportunistic action of Piggy, but it leaves the comic in an awkward position.

As Animal Pound claims to warn us of those who would take advantage of democracy for their own gain, King has constantly reiterated that this seems like the inevitable consequence of any struggle, just or unjust. A majority of King’s comics and philosophical principles come down to the idea of suffering for its own sake. “The Trilogy of Best Intentions” is the gateway to this idea, taking away the horizon of idealism as it will always fail n the real world. In both Sheriff of Babylon and The Omega Men, characters walk into a politically complex situation they think they can fix but realize how far out of their depth they are.

In Sheriff, this ends with the realization that progress is never being made, that regardless of how many months after the fall of Baghdad we get, we are left eternally in limbo. Similarly, in The Omega Men, all of the revolutionary characters Kyle joins end up re-creating the very conflict they were fighting against, with the Viceroy saying to Kyle “Welcome to our fight. Just remember, remember the important lesson of all of this. It doesn’t really matter what side you’re on.”

This opening act of King’s career is characters coming to realize the trap they are in, that circumstances don’t change simply because you think you know how to help, and to assume otherwise is folly. This concept evolves in Mr. Miracle, Batman and Heroes in Crisis into how one comes to grips with that realization. If we are doomed to repeat the same mistakes, if the world will not get any better, what’s the point of carrying on? The meaningless suffering of striving for a better world leaves us traumatized but if circumstances don’t change, what should we do?

This next thematic trilogy answers this question in different ways, taking us through how we choose to be who we are and how we can handle the burden of an unjust world by forging community, family and finding purpose for ourselves even if the world won’t give it to us. This trilogy is one that doubles down on King’s ontology of suffering, that we cannot avoid it and it animates everything in our life. But that doesn’t mean we can’t find purpose and contentment for ourselves in the midst of it.

Finally, King revisits his musings on war and revolution’s ineffectual nature, the admission that things will always go back to the way they were despite best intentions, in Rorschach and Strange Adventures. In Strange Adventures, Adam’s war against the Pykkt is a statement on the eternal us vs them binary of war itself, where both sides corrupt each other, where all societal complexity is subsumed into the business of war. If King’s second trilogy was the right answer to how we deal with suffering, then his third trilogy embodies the wrong answer. Strange Adventures is ultimately “what if Mr. Miracle made the wrong choice?” and Rorschach is equally “what if the power fantasies of superheroes and masks were just fascism by another name?” These comics assert the cynical proposition that power is never good, not even when wielded with just intent, for all power is all corrupting.

However, in these comics, King’s cynicism works because he’s posing the question of how we would respond to a world he believes to be fundamentally unjust. In each of them, the story of these characters realizing their own place within a system they don’t have a say is compelling. But when we build on this idea consistently and arrive at its natural conclusion in Animal Pound, King ends up becoming something very much not in the tradition of Orwell. In each of these stories, there is decency to be found at the end of struggle, but there is no vision of liberation, there is no end to the struggle. King’s other comics ask how we respond to that realization. Animal Pound, on the other hand, simply asserts that premise. If Mr. Miracle is about “how do we respond to broken dreams?” then Animal Pound is about how the dream itself is the problem.

Orwell himself has written about this character of people, of ideas that end in a fatalistic concept of change:

“What you get over and over again is a movement of the proletariat which is promptly canalized and betrayed by astute people at the top, and then the growth of a new governing class. The one thing that never arrives is equality. The mass of the people never get the chance to bring their innate decency into the control of affairs, so that one is almost driven to the cynical thought that men are only decent when they are powerless.”

-The collected essays, Journalism and letters of George Orwell.

Animal Pound’s function as an allegory for today and a cautionary tale about democracy becomes swept away in a confused and cynical message about democracy’s own weakness, one that King never fully grapples with here or in any of his other work. Indeed, the character of all of King’s work is that the fight may be just but there is no justice in the end. If that is so, then what does King have to say at this moment? Orwell warned of principles being corrupted, King merely cautions that all principles will eventually be corrupted.

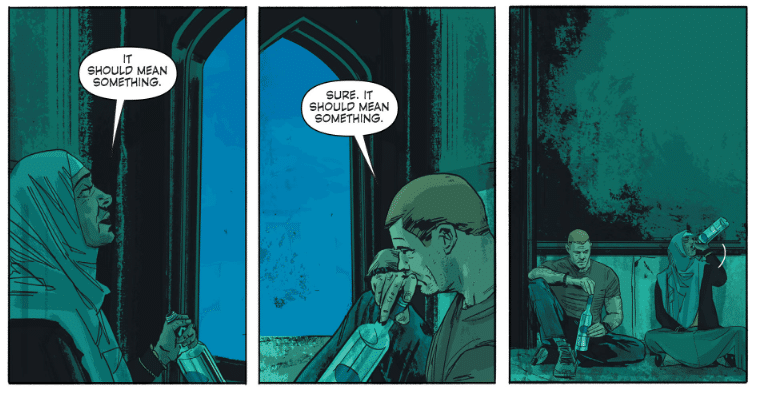

One cannot, or at least should not, discuss this overarching theme of cynicism without also addressing what King’s perspective is and who he does and does not write about. All of his comics on political themes center on the military (Sheriff) or superheroes. As such, his perspective on the realization of the world’s fatalistic nature is one that comes from a distance, from people with power outside the suffering class. King’s suffering hero is one who chooses to do good and finds horror, but could just as easily choose not to do good, to deny their own realizations and move on with their life, something the growing number of discontent cats in Animal Pound end up doing themselves. Thus, even if we accept King’s propositions, we still need to ask: what about everyone else?

In Animal Pound, this is embodied by the rabbits. Throughout the story, the rabbits are fed on by the larger dogs and as their safety becomes an issue, they choose to hide out with the cats. However, the cats do not feel any obligation to help them, and in fact find them a nuisance while they try to deal with their own problems. Fifi takes issue with this and sees the suffering of the rabbits as a failure of the revolutionary government’s goals. But the problem is that this is an indication to the reader that Fifi is good and just, and that Fifi does not have to be this way. She could have been like the other cats, she could have taken Raven’s advice but she chooses to do good and in turn reveals to herself the ledge this whole society is about to fall off of.

The rabbits are a token oppressed group, a stand in for people whose rights are dictated and whose salvation is ultimately in the hands of others. The rabbits are always the object of suffering, the ones who cannot choose to walk away unlike Fifi. But their perspective is only incidental to the governing of the pound, as the story all comes down to the negotiations between cats and dogs, the dominant parties.

This proves to be a fatal indication of the comic’s perspective. We cannot introduce and untangle Orwell’s perspective as we’ve done so far without also contextualizing King’s perspective too. We may or may not agree with the conclusions King draws about democracy’s flaws and the inherent ineffectual nature of revolution, but assuming for the sake of argument that we at least understand what he’s saying, where does that leave us? Where does that leave the people who lack the choice of these suffering heroes? King’s perspective, like all of us, is inherently limited to his experiences. But his conclusions only make sense in the context of someone who is not being eaten alive by both parties, someone who can choose to walk away from the table, someone who isn’t a rabbit.

A point of contention in the history of Animal Farm is the ending. For Orwell, the final meeting of the Pigs where they became indistinguishable from humans was meant to symbolize the Tehran conference in 1943 where Stalin sat shoulder to shoulder with Churchill and FDR, proof to him that Soviet society had not improved but rather became like everyone else. In other adaptations, like the 1954 animated film, the ending is drastically changed to show a united front of animals taking down the corrupt Pigs. This was heavily due to the CIA investors who wanted the film to be consistent with the American international campaign of “liberation” from communism, to show that the animals needed to roll-back their cause. Similar changes appear in other adaptations, including the 1999 animated film that allows all the main characters to escape and return after Napoleon has destroyed his own kingdom. While never particularly good, on some level one can understand why these changes are made, because Orwell’s original ending is extremely bleak.

King, for his part, keeps an ending that is spiritually consistent with the original. Piggy is befriended and loved by the humans, while the pound resumes normal operations ending us exactly where we started.

Absent the history of the ending getting changed, one wonders if Animal Pound really needed this final punchline. As it stands, the comic already feels very bleak about the prospect of any positive political institution, and to end it right back where it started cements this inescapable quality of suffering and compounds the larger problem of what the pound is meant to symbolize relative to Orwell’s farm. In this final blow to the animals, we realize that there is not a better distribution of working or living conditions. But rather, that all of it always ends with some form of prison.

Animal Pound is ultimately a very literal and clear example of artists wrestling with the Trump era, something King has done since 2016 but this is a point that’s consistently failed to evolve. King’s recurring themes of suffering for its own sake, and cynicism of institutions can be quite illuminating and powerful in other stories, in fact in most of his stories. But Animal Pound and its direct connection to George Orwell lays bare that his cynicism can only take us so far, and that without a more powerful imagination to show us not just the underside of our messy political project but also its future, there isn’t much to be gained by following this story’s cautionary signs. It gestures to us the dangers inherent in democracy, but never says much more than that. Many artists have taken to adapting Orwell, but all have sanded away his radical edges, regrettably King is no exception.

Despite its strong art and interesting deployment of paneling to capture the feelings of the animals, Animal Pound is otherwise a misguided attempt to distill down the dangers of our political moment. It reiterates themes present in better works by King, like Strange Adventures and The Omega Men, but it fails to evolve them. The work is ultimately less Orwellian than it claims, and that lack of understanding keeps the comic from ever finding its real message.

The Animal Pound HC is out this month via BOOM! Studios

Read more great reviews from The Beat!

English (US) ·

English (US) ·