Jake Zawlacki | March 18, 2025

“Celebrate 25 years of the Phoo Action universe created by the creative polymath Jamie Hewlett and long-time collaborator Mat Wakeham, with this definitive Silver Jubilee compilation of comics, scripts, and an assortment of behind-the-scenes material of the franchise.” – Solicit for Phoo Action

In reading the above solicit for Phoo Action, my first thought was, “Wait, who’s Mat Wakeham?” which, in retrospect, is a surprising reaction considering just how close Wakeham was to the British indie comic scene of the early ‘90s. And by “close,” I mean he was literally right there with Jamie Hewlett, Alan Martin, Philip Bond, Peter Milligan, Steve and Glyn Dillon, and others, hanging out in Worthing, contributing to Deadline magazine, tagging along on the Tank Girl set in Los Angeles, and eventually pitching a sequel of sorts to Hewlett’s Get the Freebies. Now, to celebrate its silver jubilee, Phoo Action has finally found its way to proper publication.

Phoo Action is my kind of book: a carefully curated assemblage of comics, art, photographs, scripts, and ephemera that brings a lost gem back into the collective consciousness. Phoo Action also offers a compelling story as to how it was made, and much more often, how it wasn’t. Additionally, we get the fully collected Get the Freebies for the first time in English, a new Phoo Action prose novel written by Wakeham with illustrations by Philip Bond, and the original script and storyboards for the pilot episode for BBC. As both an archive and an art object in itself, Hewlett and Wakeham’s Phoo Action presents a satisfying completion to what would have otherwise amounted to a series of false starts, cancelled deals, and dashed hopes.

For Hewlett, we can see Phoo Action as filling the creative gap between Tank Girl, its panned film production, and his superstardom as co-creator of Gorillaz. But if Phoo Action is anything, it’s a testament to the resiliency of Wakeham’s creative vision. Sure, there have been respites in the quarter century-long project since Phoo Action was planned and pitched, but the itch was never quite scratched, bringing Wakeham back to these characters again and again.

The book also stands as a cautionary tale to eager creators looking to sign the first deal in front of them, to put their heart and soul out into the world for all to see, and to finally get paid for all their hard work. While those are understandable impulses, reading the book as well as hearing Wakeham discuss it here, may spark some introspection.

Mat and I spoke through computer screens for hours about Phoo Action, living in Worthing, his role in Gorillaz, the genius of Jamie Hewlett, Wakeham’s meditation practice, what it means to be creative, and why superheroes are preposterous. The initial transcript was long, but through editing, asking more questions, expanding answers, relishing in the lack of digital page counts, adding images from his personal collection, Britishizing spellings, and arriving at 71 occurrences of the word “fuck,” it’s become epic.

It’s Mat Wakeham.

JAKE ZAWLACKI: All right, let’s start at the beginning. The big question everyone has is how you and Jamie Hewlett began working together, which you cover in the book introduction in a great story. I’m curious about who you were before you met him as a student in Worthing. What kind of things were you making? Who were your influences? What motivated you?

MAT WAKEHAM: That’s a very good question. I’ve got to think a long way back. We’re talking 1988? I was very young. 17. What were my influences? A lot of childhood ones still, I suppose. '70s U.S. superhero TV, cartoons, Hanna Barbera, G Force, and pop music, but it was the late '80s and I was massively into the first wave of hip-hop – Afrika Bambaataa, Run DMC, Stetsasonic, and Acid House too. British alternative comedy, The Young Ones and The Comic Strip Presents, were big cultural influences for my whole generation. We used to quote them in the playground. Outside of that, British folklore, the old gods and monsters, and Tolkein. Martial arts. Like everyone who grew up in the '70s I had wanted to be Bruce Lee at some point, then later, I fell for the lures of Arnie and Sly … but artistically I wanted to be a comic book artist. Which I guess all fits together. There’s a synergy.

I went to the local art school, which is Northbrook College of Art and Design, to do the B-Tech in graphic design. As a working-class kid, from a blue-collar family, I had no idea about anything creative as a career path. I just knew I wanted to work in comics, but I didn’t have a clue how you actually did that for a living. Someone – I can’t even remember who – had suggested graphic design as a way in, probably because it had an illustration element to it. My dad worked in the local factory. He was an engineer there. My mum, what was she doing? At that time, I think she was working for my cousin’s cleaning supplies firm. I didn’t have a clue about the creative industry. I remember asking my dad when I was a kid, “How do you get a job as an artist?” And he said to me, “You don’t." I look back on it now, and think … fuck, was he right? But there’s a double-edged sword there, isn’t there? The creative sector is one of our largest export industries in the UK. So, anyway, I went to art school.

Comics wise, I was reading Love and Rockets at the time. But also shit like The Freak Brothers. 2000 AD of course. All comics heads in the UK read that. What was coming out? The Killing Joke just came out, Watchmen.

What we call the “British Invasion”?

They weren’t an invasion for me. I live here. It was the burgeoning Renaissance of British comics. I was into that work. Steve Dillon was doing the werewolves Judge Dredd story. Brett Ewins was doing Bad Company. Brendan McCarthy and Pete Milligan had done Strange Days. Grant Morrison and Steve Yeowell were working on Zenith in 2000. It’s like the British Invasion of musicians in the ’60s, where they were taking the American music they loved, repackaging it, and sending it back with their own spin. British comic creators were absorbing all these influences and turning them into something uniquely their own.

My graphic design tutor, Mike Skinner, who had also taught Jamie and Alan [Martin], mentioned there were others who had studied at the school who were into comics. Little did I know! I had no clue about them when I started, but it didn’t take long to find out that Alan, Jamie, and Philip [Bond] had put together Atom Tan while they were students. They took it to the UK Comic Convention, where Brett Ewins and Steve Dillon saw it and brought them on board for Deadline. My first term started in September 1988, and Deadline #1 hit the shelves that October. Right place, right time.

So, yeah, I started school in September, and then Tank Girl came out in October. Everyone on my course was like, “Fuck yeah! We’re into this.” Then we very quickly found out, “Oh my god, they were in the years before us and had just left!”

So it seemed very possible.

It seemed totally possible – it really did – but at the same time, it was pretty intimidating. Jamie, Alan, and Philip weren’t working on a fanzine with the idea that in three years’ time, they’d be exactly where they wanted to be. I mean, sure that was the ambition, but to dream’s one thing, making it real, that’s rare. And, if you look at how Jamie’s work evolved over that period, it’s insane. The level he reached and what he was drawing by the time he was working on Tank Girl #1 compared to his art for “Max Nasty,” “Sexy Barmaid,” or the one page ad for the proto “Tank Girl” in Atom Tan #1. I shit you not. It’s crazy. Anyway, that was my plan too, to follow that path.

You meet Jamie and then Alan, and eventually you make it into the pages of Deadline magazine yourself. I found “Mr. Wonky” credited to both you and Alan Martin in issue 17, promising a story in the next issue, but didn’t make it until #23. What’s the story behind “Mr. Wonky”?

”Mr. Wonky” in Deadline #17, by Alan Martin, featuring Mat Wakeham.

”Mr. Wonky” in Deadline #17, by Alan Martin, featuring Mat Wakeham.Well, actually, Mr. Wonky was the secret agent of the Groovy Goggle Gang. If you go back through Deadline and Tank Girl, Alan and Jamie were always inserting little three panel strips or half or three-quarter page asides that might take the form of promotional giveaway items or coming soon ideas, but always with some sort of satirical twist. The Groovy Goggle Gang started like this before becoming a one pager itself. So, it was just a joke. We’d all been mucking around at Jamie’s flat while he and Alan were working, and he had all sorts of things. I think I say in the book how the inside of Jamie’s flat was like the inside of Tank Girl’s tank. Full of things everywhere. Piles of magazines and records, postcards, toy guns, plants with names, silly hats, second hand military paraphernalia and such like. Among it all he had a pair of swimming goggles hanging up. Somebody put them on and pulled their eyes open like that. [Peels eyelids open] And everyone was laughing. Everyone tried them on and then started taking photographs. We’re all art school idiots, right? Then you photocopy them and put them together and do a collage on top of Robert DeNiro’s body from Taxi Driver, of course.

Voila. Before we knew it, there was this thing called the Groovy Goggle Gang. It started off as just a one-panel joke about a bunch of shit-for-brains mercenaries for hire, trying to save the world or whatever, kind of like a proto-anarchist, human rights, eco-warrior version of the A-Team. Then, later on, we did Mr. Wonky – the Groovy Goggle Gang’s “most secret agent,” apparently. Whatever that means.

I remember this one time, there was an interview with Jamie and Alan for a TV show on Channel4 called Buzz (I think). It was super fast-paced, hyperkinetic editing, in that early ‘90s, MTV-inspired style. They wanted a piece on Tank Girl and its creators, so Jamie and Alan came up with the idea of having me appear as Mr. Wonky. It was basically an extension of the joke world they were building in the comics, a little throwaway gag within the larger story. The idea was that Mr. Wonky was their special agent for providing them with offbeat, swearing vernacular.

So there I was, sitting in a chair wearing this flowery sun hat, which Jamie or Alan had named “The Penelope Keith Hat.” Penelope Keith was an actress from the ‘70s, known for playing an uptight, middle-class housewife on the British sitcom The Good Life and the hat looked like something her character would have worn. I had the hat on, along with a pair of swimming goggles, my eyes wide open, dribbling, and talking nonsense. They basically just shoved a camera in my face and said, “Be funny.” So I did my thing, acting like a performing monkey, and then they filmed Jamie and Alan riding around the local park on their ‘70s Raleigh Chopper bikes, doing skids and wheelies. Highbrow stuff.

We were just a bunch of kids having fun, and getting to put whatever we were laughing about that week or month into print was a blast. I recently watched the excellent Mignola: Drawing Monsters documentary about Hellboy, and I was struck by how similar that period was to our own. Mike Mignola, Steve Purcell, and Arthur Adams all lived in the same building together, old art-school friends who’d become comic professionals, working, hanging out, goofing off, and putting that real-life chemistry into their work. It felt like a parallel to our scene in Worthing, with Jamie, Alan, Philip, Glyn, me, and a bunch of other young creatives, musicians, and old art school friends, all just doing our thing.

A couple of years later, you wrote an issue of Planet Swerve. At this point, did you think your future was in comics? Or, as you were saying, did it feel like you were just messing around with this magazine?

I wasn’t the main writer on Planet Swerve, that was Alan and Glyn’s thing. It was their love letter to sci-fi, art school students, and flower power. However, they did hand over the reins for one guest writer episode, and that’s where I took the opportunity to kill off one of the central characters in a dramatic collision with a gang of intergalactic alien Mods looking for a fight with hippie types. It also featured some questionable transgender imagery and themes, mixed with Hindu mythology, which nearly got Deadline pulled from the shelves, at least that’s what the publisher told me. Anyway, that was my one point of entry into the Planet Swerve universe, and it left Alan with some head-scratching to do in terms of amending the story world. Sorry about that, Al!

”Planet Swerve” in Deadline #32, written by Wakeham, illustrated by Glyn Dillon.

”Planet Swerve” in Deadline #32, written by Wakeham, illustrated by Glyn Dillon.Other than that, I had no real sense of what my future looked like. I knew I was into story, art, graphic design, films, music, TV – just culture in general – but I had no clue where it would all lead. I didn’t really know what my entry point was going to be, and post my first stint at art school I didn’t necessarily think it would be comics.

When money was getting tight, and I thought, “I really should buckle down and get a job,” I’d go to interviews, check out what creative jobs were available. I’d have meetings, and people would tell me, “You’re too creative.” And I’d be like, “What the fuck does that mean? How can you be too creative for a creative job?” Now, as a senior creative myself, I get what they were trying to say. I wasn’t as singularly focussed as someone like Jamie, who just draws comics. That’s his thing. He’s really good at capturing the zeitgeist, capturing lightning in a bottle over and over. He’s got this mental rolodex of pop culture, and he can tap into it effortlessly, adding detail and nuance in a way that’s pretty mind-blowing. But Jamie doesn’t cartoon, produce films, write books, do graphic design or host embodiment podcasts. He’s focussed on cartooning. Me? I’ve always had a broader range of interests, and that’s why I was just into making things, expressing myself. I never thought comics would be the only thing I’d end up doing.

When I first went to art school, I thought maybe I was going to draw comics. But as soon as I got there, I opened up a bit. We were doing life drawing, printmaking, photography, different experiments – it was a graphic design course, after all. And I realized I liked all kinds of creative work. So I quickly pulled away from the idea of just focussing on comics. Also, then I met Philip and Jamie, and I started feeling a lot of self-doubt. I thought, “Why am I even bothering to try when these guys are doing that?” They were so focussed, so skilled and talented, and it felt like they had it all figured out. But looking back, I shouldn’t have compared myself to them. The thing is, I did. I was so caught up in what they were doing, thinking I had to measure up or follow the same path. But that’s the trap, right? You can’t compare yourself to other people. Everyone’s got their own thing, their own journey. You just need to focus on your own work, on what you want to say, and not worry about what anyone else is doing or what they think you should be doing. It’s about finding your own voice and expressing yourself, no one else’s expectations. But at the time, I didn’t really get that. I was young, and it’s so easy to get lost in that comparison game, thinking you should be doing what they’re doing or that you’re not enough. You just have to block that out and keep working on your own thing, even if it takes time to figure out what that is.

When you’re young, you’re trying to develop your craft, and I had such a wide focus that I wasn’t honing any one skill. Jamie, on the other hand, would sit and draw for hours and hours. I did that for a while, I was always drawing up until about the age of 18 but then, I’m gonna be really candid, I discovered hallucinogens. Hallucinogens took me away from the drawing desk. They propelled me out into the universe and deep into inner space and big questions about life. It’s like, drawing suddenly felt small compared to everything else going on in my head.

Existential?

Yeah, really existential. Big time. I was interested in everything. Philosophy. Theosophy. Cultural theory. I wasn’t career focused at all. I did bits and pieces because it was fun and I could.

That makes sense because you mentioned doing design for Fireball and then I saw you have a credit for the logo design of Peter Milligan’s Egypt.

Yeah. Graphic design. Logos. Both for Fireball and Egypt. I did some Fireball merch with Jamie too as well as odd bits and pieces for him and Alan on Tank Girl.

“Fireball” in Deadline #28 by Jamie Hewlett, “FIREBALL” design by Mat Wakeham]

“Fireball” in Deadline #28 by Jamie Hewlett, “FIREBALL” design by Mat Wakeham]Those are some random credits to have. You’re in this milieu of UK colleagues, all these people, but you seem to be on the edge…

We all lived pretty close to each other. Look, I shared a flat with Alan Martin and before that Alan’s mum and dad lived just up the road from mine, so Alan would walk down to my place, knock on my door, not too early mind you, or I’d pop up to his where he had a photocopy machine, and we’d knock something together on that, maybe a poster or a fanzine of some sort, before heading into town together. Sometimes, we’d go down to the seafront, grab a cup of tea at this café where we all used to meet. We’d sit around chatting about films, books, music, art, culture, you name it. Alan always had his notepad with him, scribbling stuff down, and Jamie would be back at his place, where we’d inevitably end up, waiting on Alan, saying “I really need you to finish this script.” I mean, this was such a regular occurrence with those two that this dynamic ended up, at least once, on the pages of the comics themselves. It was a scene.

I had flats with both Alan and Glyn Dillon at different times. We were all living in each other’s pockets. Alan and Jamie shared a flat, and Philip lived right next door to Jamie. Alan, Jamie, and Philip had all had multiple flat shares over the years. It was a small town, and since we all went to the same art school, it just made sense that we’d stick together. We were a proper group of mates. We worked together, hung out together.

Every Friday without fail, we’d go to the same pub. They’d have a happy hour where you could get two pints for the price of one. After that, we’d hit the local nightclub, dancing to indie music. In fact, we even decorated the inside of that nightclub with collages, paintings, and drawings in exchange for free entry. It was just one of those times when everything felt connected, like we were all part of something, even if we didn’t quite know what that “something” was at the time.

It sounds like the early nineties indie comic equivalent of the Parisian cafe scene in the twenties.

We wanted it to be. And we tried. Something like the Beatnik scene, or the Merry Pranksters: wild, freewheeling, full of creative energy. We wanted to be like the South Bank too, where you could imagine ideas flying around like sparks in smoky rooms. We idolized those kinds of creative communities: Warhol’s Factory, hippy communes, and their British equivalents, like the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Bloomsbury Set. We weren’t just inspired by highbrow art movements; we loved the absurd and anarchic too. So as much as we loved Dada’s nonsense and Bauhaus’ rebellion we saw clear connections to The Goon Show’s mocking of post-war British conformity, Monty Python upending everything sacred, and the hilarious '80s alternative comedy railing against Thatcherism. It was all part of the same thread: rejecting tradition, breaking the rules, and having a laugh doing it.

But the reality? We were in Worthing. A crap little seaside town in Thatcher’s Britain, where communities were gutted, and the whole place just felt deflated, like the air had been let out of everything. We were idealizing all that bohemian, countercultural glamour in a landscape more Mike Leigh than Andy Warhol, a kind of Life is Sweet version of creative rebellion with comics thrown in.

We called ourselves The Big Underwear Comics Society. There’s a name to conjure with, isn’t it? It was tongue-in-cheek, a nod to the ridiculousness of it all. We were like the South Bank, but on the South Coast. And instead of dazzling sophisticates, we were . . . well, idiots. As Logan Roy would later say about his kids in Succession: “These are not serious people.” Only, we were serious. Deadly serious: about satire, about fun, about art, about music. [Laughs]

It was our way of thumbing our noses at the world, taking the piss out of high art while trying to make something meaningful ourselves. There was something deeply transgressive about it too. We weren’t just drawing comics; we were skewering the conventions of a country that seemed to have had the creativity beaten out of it by decades of economic austerity and cultural conservatism.

In a way, it was absurdly ambitious. The Warhols and Pre-Raphaelites had their lofts and salons; we had the back bedrooms of rented houses and flats with posters covering the crappy wallpaper, tatty, smoky pubs and seaside cafes. But that ambition, that sense of striving for something, was there. We were taking those highbrow ideals, the Pre-Raphaelite devotion to beauty, the Bloomsbury intellectualism, the Merry Pranksters’ narcotics-induced counter-culture energy, and dragging them through a distinctly British filter, where they came out the other side battered, beer and tea-stained, and somehow more authentically our own.

Comics were the perfect medium for it at that time. They’re inherently rebellious, and transgressive, a space where high art and lowbrow humour collide in four colour separation. They’re made for outsiders, for people who don’t fit in and don’t care to. And that’s what we were: outsiders. But at least we were outsiders together, dreaming big in a crap little town.

This environment helps to explain your gonzo sensibilities. Considering the ways psychedelics influenced you on an existential and spiritual level, how much was literature, especially of writers like Hunter S. Thompson, part of your development and interests?

Hunter S. Thompson’s writing, and the way he lived, was a huge influence on me. Not just the gonzo style, though that was part of it, but the whole ethos: the full-throttle, no-holds-barred approach to art and life. But he wasn’t working in isolation. He was part of this bigger thread, this massive lineage of countercultural writers and artists, and I was drawn to all of it. The Beatniks before him, for example, “stoned immaculate” as Jim Morrison would’ve said, were like the start of this weird family tree of rebellion and creativity.

Ginsberg had a particularly big impact on me. Alan Martin loved Kerouac, but I never really vibed with him in the same way. Kerouac felt like someone who’d burned out, you know? He started out exploring Eastern philosophy and then ended up this embittered, alcoholic Catholic. Ginsberg, though, he was something else. He inspired a generation to break out of the stiff, repressive attitudes of the time and focus on art, beauty, pleasure, self-knowledge. His writing, his life, his whole energy, it opened the door for me to explore my own path. It’s through Ginsberg that I found Tibetan Buddhism, which eventually led me to Theravāda Buddhism. It felt like a natural progression, moving toward something that emphasized mindfulness, clarity, and a kind of direct, no-nonsense pursuit of self knowledge.

Of course, it wasn’t all calm enlightenment back then. I was as much drawn to the hedonism as I was to the insight. That’s where Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters come into it, their Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test world, with Neal Cassady behind the wheel, transforming from Kerouac’s Dean Moriarty into this larger-than-life, LSD-fuelled superhero, literally driving the whole thing forward. That mythology was irresistible to me.

And it doesn’t stop there. The thread runs deep, all the way from Aldous Huxley’s Doors of Perception to Tim Leary’s acid evangelism which inspired the Freebies’ Albert Squares spiking of The Face Magazine Christmas party in Jamie’s Get the Freebies, Kesey’s “Further” bus, and Ginsberg’s Be-Ins high on Owsley Stanley’s White Lightning. It’s all connected, from the psychedelic highs to the eventual crash. Manson, the CIA, the brown acid at Woodstock. It’s a story of rebellion, creativity, and excess, constantly cycling back on itself.

Get the Freebies detail, Episode 7, by Hewlett and Wakeham, from Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.

Get the Freebies detail, Episode 7, by Hewlett and Wakeham, from Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.That lineage winds its way through everything that’s shaped me. It’s Lou Reed frozen in a Mick Rock frame, Iggy Pop painted silver and off his head, Bowie in Berlin, punk smashing through, rave culture rising out of the ashes. It’s Blake and Shelley, the mystics and the visionaries, meeting Buddha somewhere along the way. And yeah, even Andy Warhol, Albert Hofmann, and George Harrison funding The Rutles at a CBGB’s after-party in Ibiza. That’s the chaos and creativity ouroboros I’ve always been drawn to, constantly eating its own arse and spitting out something new.

And that’s barely scratching the surface. You could say that’s just the psychedelic, queer, white-boy counterculture tip of the iceberg. I haven’t even touched on the rest of it, the massive intersectional, inter-dimensional influences. Angela Davis, obviously. Spike Lee. She’s Gotta Have It and Do the Right Thing blew my mind. George Clinton. Gil Scott-Heron, of course. The Revolution Will Not Televised, Whitey On the fucking Moon! Fela Kuti. Jimi Hendrix. Grace Jones. Prince. His goddamn royal purpleness. The Last Poets. Shit, James Baldwin! Bell Hooks! Grandmaster Flash. Benjamin Zephaniah. Don Letts. Chuck D! You get the picture. Fight the bloody Power! The whole crew of the Intergalactic P-Funk Mothership. And then there’s the late ‘70s ska-punky-reggae scene, where suddenly Ginsberg pops up again on a Clash album like some beatnik Zelig, high on impromptu prose poetry and the gravitational pull of pretty British punk boys. It’s all in the mix, swirling together into this messy, brilliant, impossible cocktail of influences. I see the world through a tangle of pop culture, counterculture, and cultural theory – everything connects, everything cross-pollinates, and I’m always tracing the through-lines between them. Real or imagined, y’know?

I remember being at Megatripolis in London, tripping on LSD, watching Timothy Leary live-streamed on this clunky early internet broadcast. It felt like all the pieces were colliding, technology, counterculture, psychedelics, and the sense that we were all just on the edge of something huge and undefined. What I took from all of this wasn’t just the hedonism or the thrill of altered states, though there was plenty of that. It was the search for something bigger. For insight, understanding, connection. Over time, that wild pursuit of exuberance and experience gave way to something quieter and more deliberate. I moved beyond the psychedelics and into meditation, beyond the chemical highs to a practice rooted in presence and stillness. But that energy, that rebellious spirit, is still there. It’s just channelled differently now.

All of these influences resurface in the Phoo Action prose novel I’ve written for the book. The spiritual questioning, the countercultural energy, the constant challenging of norms. It’s all in there, woven through the story. There’s this relentless drive to explore bigger questions about identity, power, and freedom, but it’s done with the same surreal humour and anarchic spirit that defines the whole Phoo Action universe. It’s not just about rebellion for rebellion’s sake; it’s about pushing boundaries and smashing expectations, while still having a laugh along the way. That blend of the spiritual and the absurd, the profound, the profane, and the ridiculous, is at the heart of the novel. It’s all the chaos and questioning of counterculture filtered through the lens of satire and superheroic madness.

Phoo Action, Prose Novel, Chapter 3, written by Wakeham, illustrated by Philip Bond, from Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.

Phoo Action, Prose Novel, Chapter 3, written by Wakeham, illustrated by Philip Bond, from Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.Are these some of the underpinnings of The Body Knows Podcast you hosted?

Okay, yeah, sure. Let’s talk about that. I hosted the podcast with my wife for a year. We devised that during Covid. Something we could collaborate on together while we, and the rest of the world, were stuck in the house with no one else to talk to. It seemed like a good idea. And a lot of this stuff pops up in there. Especially in the episodes with my friend, integrative psychedelic therapist Michelle Baker Jones, my Buddhist meditation master Ajahn Sucitto, and the inspirational psychedelic anthropologist, explorer, documentarian, and ecological activist Bruce Parry. Through these conversations, we explored the intersections of psychedelics, spirituality, and embodied wisdom. They reflect tangentially back on how my journey, from gonzo counterculture to meditative stillness, has evolved and continues to inform my creative and spiritual practices, albeit from an entirely different entry point of well-being.

This helps frame your story in Penthouse Comix #33, the last issue, with artist Philip Bond. At first I was unsure of how a comic in Penthouse would be the key moment for Jamie to bring you into Phoo Action, but there’s this absurdist, gonzo, erotic style that Phoo Action would pick up on. Not as explicitly so, but it’s still there.

The thing is though, I’d just come straight out of undergraduate art school. I’d left Worthing, everyone was doing their thing, and I realized that actually all of that stuff wasn’t my thing. I was contributing bits and pieces. I was doing bits of graphic design. I was contributing bits of dialogue. I was part of it, but actually it wasn’t my thing. I went off to do something else by myself. I went and did a fine art degree. There I got very deep into cultural studies.

So, I return to Worthing and Philip’s got this offer to do a Penthouse comic and it’s Dave Elliott, who was the former Deadline editor, who’s the editor of Penthouse Comix then. So he knew me and — I can’t remember how it got to me writing it, but I did write it. It’s quite uncomfortable. I tried to write something that would actually be unsettling. I look back at it’s like why are you trying to fucking upset this applecart? Why didn’t you just write an erotic comic? I wrote this thing that was part absurdist, part transgressive and it’s only the second comic I’d ever written and it’s overwritten.

I’m not particularly proud of that work. Philip’s artwork in it is fantastic. He really nailed it. But my writing? Not so much. Not just the form, but the content too. Looking back, there’s this uncomfortable realization that it was steeped in the kind of male entitlement we didn’t even realize we had at the time.

In the '90s, there was this feeling that we’d seen off all the specters of racism and sexism, all that overt race-baiting and misogyny that had been staples of mainstream British culture in the '70s and '80s. We thought we’d moved past it. Apartheid was over, Thatcher was out, the National Front and the British far-right were defeated, or so we believed. So there was this big ironic laugh we thought we could all have at it now, like, “Oh, wasn’t that awful? But look how enlightened we are.”

The truth is, that was just our privilege talking. It was us — young, white men — thinking we were above it all, parodying the bigotry of previous generations but not really understanding what we were playing with and how it still underpinned everything. And when you look back at some of the stuff from that period, this comic included, along with things like Loaded magazine and Blur doing their whole Benny Hill routine with Page 3 girls, it’s just more of the same, repackaged as irony. We weren’t as clever or as progressive as we thought we were, and it’s uncomfortable to admit, but it’s true.

I was trying to write something absurdist like the Marquis de Sade meets Carry On and it’s just not that. It doesn’t land. It’s not as clever, subversive, or even funny as I thought it was at the time. Instead, it ends up being this clumsy attempt at something provocative that just comes across as misguided. Looking back, I can see what I was trying to do, but I just didn’t have the skill, or, frankly, the awareness, to pull it off. It feels like I was pushing buttons for the sake of it without really understanding the bigger picture.

Page from “Big Top Eddie” in Penthouse Comix #33, written by Wakeham, illustrated by Philip Bond.

Page from “Big Top Eddie” in Penthouse Comix #33, written by Wakeham, illustrated by Philip Bond.For the quality of the average Penthouse Comix, it’s pretty unique.

But that’s just what I was like at the time. If someone gave me an opportunity, my first thought was, “Okay, how can I fuck with this?” That was my attitude, always about pushing the limits and then stepping right over them. Edgelord-ery, plain and simple. That’s what it was. It was everywhere back then, from Ren & Stimpy to stuff like Jackass and Vice Magazine, where it was all about shock for the sake of it, just seeing how far you could push things. But there were times when it actually worked. Chris Morris with Brass Eye – genius. He made you laugh and squirm, but there was always a point to it. That’s the difference, really – pushing boundaries because you’ve got something to say versus just seeing how far you can go. At the time, though, I definitely had a tendency to be in the second camp.

That said, I can still see what Jamie might’ve seen in it. I know what I was aiming for, even if I didn’t hit the mark, and I think Jamie thought he could take that energy and guide it into something more. In Get the Freebies, Jamie was absolutely riding that wave too, but he did it with so much style. He had this incredible knack for taking that edgy, provocative energy and making it feel sharp, clever, and visually stunning. It worked. But for me, coming back to it all these years later, to write those characters and that world, I’ve had to look at it differently. I’ve had to balance it out, really reflect on the time, the culture, and what we were all tapping into back then. It’s not just about the style or the edge; it’s about understanding what it all meant and where it sits now.

Anyway, by that point, his and Alan’s working relationship had kind of broken down. Hollywood had properly broken them both. Alan had said, “I’m fucking out of here,” and just distanced himself from it all. The Tank Girl movie got completely panned at the time, and while I think that’s a bit unwarranted — it was a big swing, and lots of people love it now — Alan and Jamie weren’t two of those people. They both hated it. So Alan just fucked off. By then, Jamie had done the twelve Get the Freebies comics on his own, and they were brilliant. I think Jamie’s so undervalued as a writer. People see the fun and the jokes and the playfulness, but they don’t realize how much story and character he packs in there. Those comics are three pages long, sometimes four, and maybe a third of the space is given over to this elaborate fart joke, and yet he still tells these big, layered stories. It’s deceptively good writing.

But I think Jamie was lonely at that point. He’d been working on his own for a while, and I think he liked the sense of ingenuity and energy I brought to the table, even if I didn’t have the polish. I don’t want to bang on about that Penthouse Comix story too much, though, because, like I said, it’s crap. I don’t want people rushing out to dig it up and start talking about it too much, you know? It’s one of those things that’s best left buried. Trust me. The work we did together on the second season of comics, to be titled Phoo Action. That was something else entirely though.

At the time, you’re trying to become a music video director in London. This is ’97, after your arts degree. You’ve been working in comics, you’ve been working in a bunch of other stuff. What led you to finally pick music video director? As you’re saying, you’re kind of a polymath, you’re looking at all these different options. What led you to that?

Well, when I was doing my fine art degree, I found myself getting more and more drawn to film as a medium. It just felt like the ultimate art form. It has everything a comic book has, but then you add set design, music, costumes, sound design, cinematography, performance; it includes all the plastic arts. It’s this complete manipulation of reality, and yet people accept it as truth more readily than any other art form. I just found that absolutely fascinating. The thing is, I’d done a fine art degree, not film school, and, like I said earlier, I didn’t have anyone in my family guiding me, saying, “This is how you become an artist.” So, you don’t. You just fumble your way through and figure it out as you go. If I’d known at 18 what I know now, I’d have gone to study film and worked my way through the film industry. But that wasn’t my path. I kind of stumbled into it sideways.

It all started with music videos. They were massive back then. I started directing them in ’97 or ’98, just after leaving art school. I moved to London, got a job, and ended up staying with a girl whose ex was this established music video director. He’d just set up his own company, and she phoned him up on my behalf. I wasn’t even thinking about work at the time, never thinking, “What’s my next career move?” She arranged for me to meet him, and I just blathered on about art and music and film, and somehow, he gave me a job as a runner. I wouldn’t have gotten that chance myself. I wasn’t out there hustling for work or planning some grand trajectory. I was always more focussed on what I could experience and what was next. Honestly, at the time, I was way more interested in where the next party was. Not in a reckless way, but in this wide-eyed, "What’s out there to discover?" kind of way. It wasn’t about work. It was about life. Not in a …

Shallow, just-to-get-drunk way?

No, I wasn’t like, “Where’s the brewskis at?” The party scene when I moved to London was completely different. It was all the people who were rapidly becoming the Britpop stars. It was continuing what we’d been doing in Worthing when we were trying to recreate some kind of Left Bank vibe. It was about becoming part of this massive cultural moment, this big, burgeoning scene. That’s what I was always chasing, being in the middle of something creative, expressive and alive.

It’s not that I didn’t care about what I was doing for work, it was creative and laden with potential. But I was still more interested in what gigs I could go to, what music I could hear, what art and film I could see, and what conversations I could have. Mostly, anyway. That was what mattered to me. Although I was beginning to get more focussed on what I could create and what my contribution could be. I wasn’t just looking to work as a means to an end.

Most party scenes don’t feel that creative.

It was super, super creative. Everything about it. The whole scene felt like this massive kickback against the mainstream. You could hear it in the pop lyrics too. In Pulp’s song “Mis-Shapes,” Jarvis Cocker sings about misfits uniting and challenging the mainstream. That was exactly it. All of us weirdos, all the art school idiots in thrift store clothes, the ones the football hooligans used to want to beat up, suddenly, we were taking hold of the culture. And not just that, we were being embraced and celebrated for it. It was incredible to be around all of that, right in the middle of it. But at the same time, I was starting to think, “What can I do? How can I build my career and contribute to all of this?” I knew I had to figure it out and make something happen.

I guess I’m contradicting myself a bit here. When I say I wasn’t focussed on what I was doing work-wise, I mean being a music video director wasn’t a job-job, not a regular wage or anything like that. Not unless you were one of the big ones, the Michel Gondrys, Chris Cunnghams or Mark Romeneks. Being a music video director back then was pitching ideas to record companies. They’d send out cassettes of new singles to a select group of directors, and you’d have to pitch your ideas for free. That was the gig.

But before all that, I was a runner. One day, a tape came in that none of the directors on the roster wanted, and the team knew I wanted to direct. They said, “Mat, why don’t you write a treatment for it? It’s good practice, and we’ll send it off.” So I did. And they sent it off. And I got the job. Looking back, I can see why. I could write, I was visually literate, and I’d just done a fine art degree. Plus, I’d spent my formative years immersed in the avant-garde of the British comic scene, so I had all of this weird visual and narrative vocabulary floating around in my head. I wrote the treatment, and they let me do it. It was just a small dance music video, but it was something. Apart from the Tank Girl movie, it was the first proper set I stepped onto as a professional, and I was the director. I was shit scared. Absolutely terrified.

Someone’s going to find out.

Yeah, the reality police were definitely circling. “No, no, son, you’re nicked. Off you fuck.” That’s how it felt. The night before I went on set, I shaved my hair into a Travis Bickle mohawk, like that was going to somehow give me presence or get me into the right mindset. But honestly, I was drowning in self-doubt. Massive imposter syndrome. I didn’t know what I was doing, but I just got on with it.

I had hired a great Director of Photography, though, and he was brilliant. He framed up exactly what I wanted, and as the shoot progressed I became more self-assured. I did know what I wanted. I just hadn’t trusted myself until I was in the thick of it. Once you’re there, on the job, you either sink or swim, right? So I swam.

Did I ever really “make it” as a music video director? Depends how you look at it. Is me becoming part of Gorillaz my making it? Is that where my music video career was leading? It’s debatable. I did some decent clips, alright promos for smaller bands, but it was all just me figuring things out, learning as I went. Nothing groundbreaking, but it was a start.

Single page ad for a cancelled strip by Jamie Hewlett. From Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.

Single page ad for a cancelled strip by Jamie Hewlett. From Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.Let’s get to Phoo Action. You and Jamie get the pitch accepted and begin working on it. You’ve mentioned that you both worked in the “Marvel method” with Jamie drawing the page layout and then you coming in to add scripting, just like Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, right?

And that’s how Tank Girl was done before as well.

Yeah, you mentioned Alan Martin.

There was a loose agreement on what the story was. “Loose” meaning flexible, an agreed framework, not a full script. We knew the action, character beats, start, middle, end, jokes. Outlined, not scripted. There was a loose agreement on the story.

Jamie just gets on with it. Jamie’s got ants in his pants. Just fucking starts. No overthinking. Just start. It just has to keep going, and you have to keep up.

This method is really rare for contemporary comics. It’s also pretty controversial, too, because people will endlessly debate who actually created the Marvel Universe. Who wrote it? Who created the characters?

Yeah, we all know Stan’s best creation was Stan, right? I was always really mindful to always give the credit to Jamie in the Silver Jubilee book. The original characters are his creations. There are others I’ve added over the years, through the TV adaptation rabbit hole and others that we created together for Phoo Action after Get the Freebies. We own them all together now. The way that works, this Worthing version of The Marvel Method, is he’d be busy drawing characters and then we’re talking about who they are. Then I’m taking ideas and running with them and going, “What about this? What about this?” Jamie would take what he wanted from that, put it in, start on pages before or while things are being scripted, maybe turning it into something else entirely, or just messing with it for the sake of it. He likes to fuck with things too. It was fluid, reactive, less about precision, more about keeping the momentum going and seeing where it led.

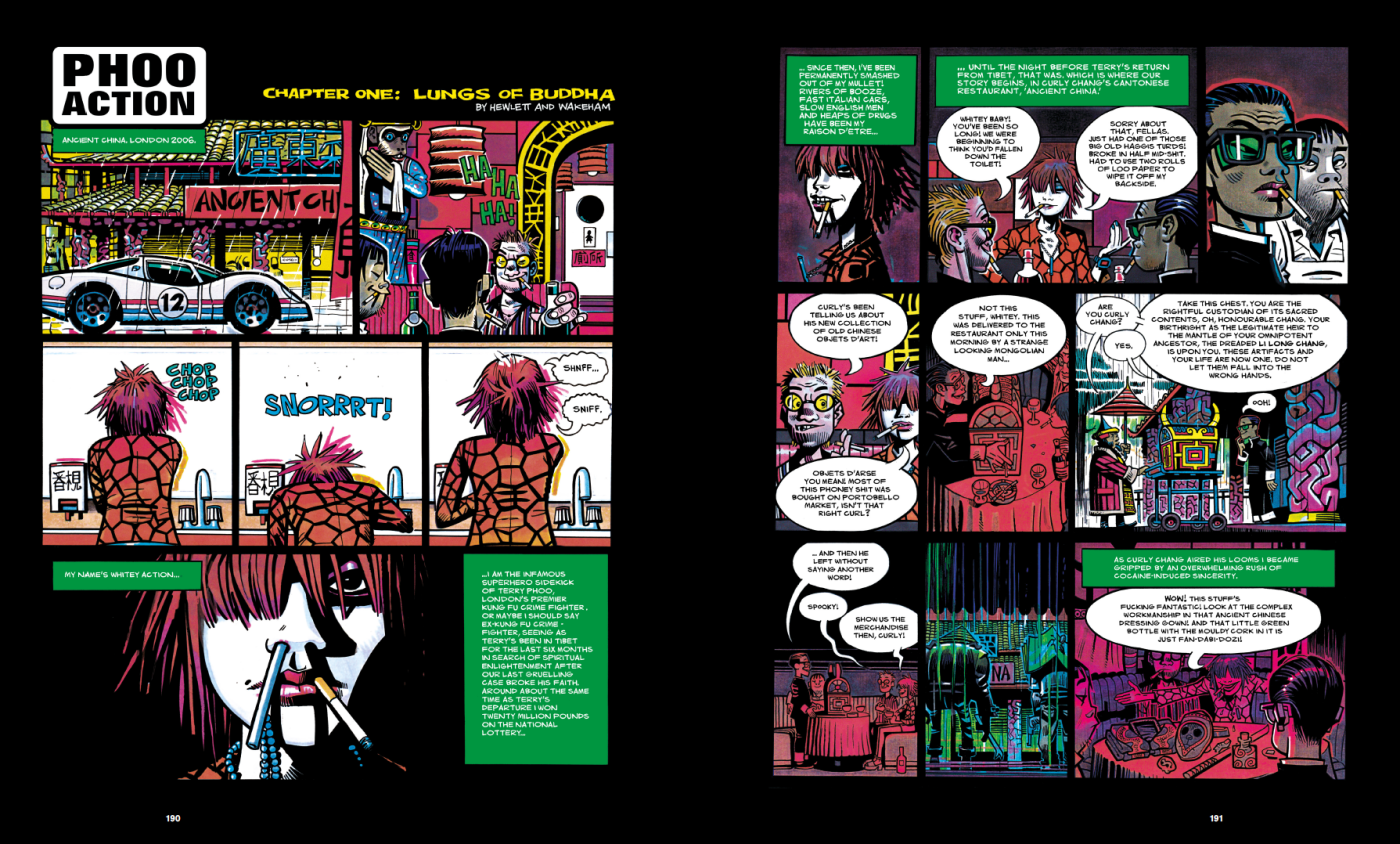

By then, we were really close. Proper good mates. And when you’re creatives, the conversation always turns to ideas. You throw stuff out and one thing leads to another. Half the time, you don’t even realize you’re building something. It just happens. This is exactly how Jamie and Damon came up with Gorillaz just three years later when they were living together. I’d stayed at his house for one whole summer holiday the year before when I was still at art school. He put me up, so I’d always been there while he was working, I was just there when he was hitting deadlines. I knew how he worked. We were always cracking jokes. We understood one another. We just had a shorthand. I don’t think it’s controversial to say that you can tell the Tank Girl stories that Jamie’s taken the lead on and the ones Alan’s taken the lead on. The opening episode of Phoo Action, “Lungs of Buddha,” Jamie had outlined that and he told me what parts he’d wanted me to script and through that process I put some other ideas into it.

Phoo Action, Ch. 1, by Hewlett and Wakeham, found in Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.

Phoo Action, Ch. 1, by Hewlett and Wakeham, found in Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.Jamie pitched the rest of the story to me too, “This is the start. This is where I want to get to. Let’s join the dots together.” The plan was to then build it episode by episode, month by month, rather than me sitting down and writing a full script for him to draw, like he’d done with Tank Girl: The Odyssey. That just isn’t how Jamie works. When he’s locked into a rigid script, something dies inside him, and on the page.

Instead, the idea was to spend the first two weeks of the month drinking tea, cracking jokes, and throwing ideas around, and then, as the deadline loomed, actually start making the thing. Of course, Jamie would probably start in week one, then by week two, he’d be like, “Mat, have you fucking done anything?” And I’d need to scramble. But we kept it fluid because we wanted to keep the satire sharp, right up to the deadline, so it could stay reactive and contemporary. Even now, someone recently wrote a review of Phoo Action saying they kept forgetting it was set in the future because everything about it felt so tied to the late ’90s culture we were living in.

We still wanted to keep that element of being able to make jokes about whoever was in the cultural spotlight at the time: Liam [Gallagher], Louise Wener, Northern Uproar, Steve Lamacq, Peter Andre, whoever we decided on that month. We’d already planned for one of the villains to be Brian Harvey from East 17, and the gag was that he’d somehow taken his own skull off; he’s low-hanging fruit, to be fair. A lot of Get the Freebies was cruel, even spiteful, if I’m honest.

That was just the attitude in the press back then. This was pre-internet, so what people now call “clap back” on social media, where everyone’s chasing clout, was happening in the music press instead. And Jamie was part of that. It was this weird, drawn-out dialogue between creatives shit-talking each other to see what would come back. But it wasn’t instant. You’d throw something out, put it into the world, and then just wait to see what happened next.

Brian Harvey. Looking back now, as an adult, you see the bigger picture. He’s struggled with mental health issues, clinical depression. But at the time, he’d famously run himself over with his own car and blamed it on eating too many baked potatoes. And we just thought, “That is the best supervillain origin story we’ve ever heard.” It was so ridiculous, so Phoo Action. A pop star turning into a supervillain based on something that had actually happened in real life. It was too good not to use.

That was the kind of thing we were playing with, but at the same time, we wanted it to be an ongoing, proper, collectible graphic novel story. With a single, big story arc, unlike Get the Freebies. We were only doing four or five pages a month, so in total, it would have been what, 60-, 70-odd pages? But even then, when it got cancelled, there were great ideas in it, a complete story outline I wasn’t going to throw away. This – [holds up story outline treatment] – this is the original story treatment.

[Reading treatment] Each episode is 10 pages in length, appearing as five-page monthly installments. The action will be devised and divided to deliver high action, sharp humour, and nifty storytelling throughout every installment. Not forgetting the crowd-pleasing Hewlett big fat knob joke. TMS.

Original story treatment and Ep. 1, Xeroxes, from Phoo Action.

Original story treatment and Ep. 1, Xeroxes, from Phoo Action.That’s it. That’s our fucking pitch. You know what I mean? The brass balls of it, like, “Oh yeah, we’ve got this one sorted. It’s in the bag.” No you fucking haven’t.

Then there were the chapters: Enter the Flying Scotsman, Banquet of Evil, Up The Middle Path, Opium Zen. That was the original structure. I stuck to that, but I added more chapters along the way. Expanded it, built on it. But that was the backbone I honored writing the prose novel adaptation, twenty five years later.

It was green lit and then canceled under new editorial direction — which happens a lot around this property. Did you ever think it would see print or were you already looking towards live action?

Jamie had also asked me to write the comics because I’d gone to him and said, “I think Get the Freebies should be a feature film.” That was the big plan I’d started piecing together. I’d been on the Tank Girl set back in ’93 or ’94, whatever year it was, and the arrogance — I mean, I was 22, 23 — standing there thinking, “The reason this isn’t working is because the studio just doesn’t get it. We should be making this ourselves.” Without a single clue what that actually meant.

And Jamie was like, “Yeah, let’s do it. Let’s get this adaptation up and running.” From his perspective, it was, “Well, I’ve done it with Tank Girl, why the fuck can’t I do it with this?” But this time, sisters are doing it for themselves. No studios, no execs, no one to mess it up, just us, taking charge.

That was another reason he’d said, “Okay, let’s write this next season of comics together.” It was about cementing us as a team, as the rightful owners of this property. The idea was, “We write the comics, put them out there, and that gets people interested in making the film.” It was a strong pitch. Jamie and I co-writing the book meant we were fully in control.

When it all collapsed, I don’t really know why. Jamie’s manager at the time, Tom Astor, who used to be the publisher of Deadline, was involved, but looking back, I don’t understand why we didn’t go and talk to other comics publishers. We just put everything in Tom’s hands. Jamie was the senior creative partner, and I was coming in with no industry experience or connections, so I didn’t have the knowledge to push for other options.

If that happened to me now, like when I walked away from the Z2 contract on this book, I wouldn’t just sit there going, “Can somebody please help me?” I’d do what I did with the Silver Jubilee: go out, meet publishers, and make it happen myself. I went to the London Book Fair, laid it out: “This is what I want to do. This is what I’ve got.” No waiting around, no hoping someone else would sort it. Just taking control and doing it on my own terms.

But I think, for Jamie, this was never really about getting deeper into comics. He wasn’t looking to expand Get the Freebies into some big, long-running series or a trade monthly. He didn’t want that. He liked the five-page format. Short, sharp, fully in his control. He could pencil it, ink it, color it, co-write it, letter it. It was his, completely.

It’s funny when you look at Tank Girl: The Odyssey. The drawing and inks are beautiful. I love that artwork – but the coloring has this flat, mechanical feel. And it’s not that the colorist did a bad job; they were a good colorist. But it wasn’t him. It wasn’t Jamie putting his full stamp on it, and I think that’s what he wanted to avoid.

There’s a great Cartoonist Kayfabe episode where they go through his Taschen book, and Ed [Piskor] talks about this exact thing, how no colorist would ever make the choices Jamie does. It’s all hand-colored with felt tips, which is just mad when you think about it. The idea that you can start in one corner and work your way down with felt tips and have it come out looking like that is insane. [Holds up a page of Get the Freebies]

So, circling back to the beginning of our conversation. Imagine I wanted to be a comic book artist. I’m looking at this, I’m looking at that, and I’m just thinking, “What the hell?” Yeah . . . maybe I’ll do something else. It’s that whole "comparison is the thief of joy" thing. You see someone operating on a completely different level, and instead of it inspiring you, it just makes you question why you’re even bothering.

Panel from the Freebies, Ep. 4, by Jamie Hewlett. Reprinted in Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.

Panel from the Freebies, Ep. 4, by Jamie Hewlett. Reprinted in Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.There is something about those Deadline artists and their coloring process that seemed really different from the norm of American comics.

Their approach to comics was different. We were influenced by different things. Geographically, we’re closer to Europe, and while we share a lot with the U.S. because of the language, we were more drawn to European cinema, painting, and fine art traditions also. We loved American comics and pop culture, but we were just as into British comics, the European scene, and early manga and anime.

The palette in Akira was massively influential. The way they handled color, otherworldly hues against hyper-saturated neons, felt cinematic, like fine art meets Blade Runner. We were art school kids, so that stuff hit hard. Paris, Texas, for example. The bold colors, the atmosphere. It all fed into how we approached comics. Creative, individual, atmospheric, but still fun and punchy.

Let’s talk a little bit about the live action adaptation. To me, it counts as one more strike against mainstream trying to adapt gonzo. I’ve never seen it done successfully, to get that “One step to the left,” right. I don’t know if you can do it at BBC.

No, you just nailed it. You can do it, but you probably can’t do it on the BBC. They genuinely loved Phoo, they really did. But at the same time, they were the BBC. It was like, “We love your wackiness, but actually, we’re the authority. And no, no, you don’t do it like that.”

So immediately, our hubris, thinking we were the ones calling the shots, was out the window. They kept telling us, “We don’t want it to look like Doctor Who; we want it to be your vision.” But I was going mad, because at the same time, I was reading Ricky Gervais’ scripts for Extras, where his character gets commissioned by the BBC to make When the Whistle Blows, and they just butcher it.

There’s that famous scene where David Bowie sings “Funny Little Fat Man,” completely humiliating him. And I remember thinking, “Oh fuck, is that happening to me? Am I the sellout?” And at the same time, while I’m reading the scripts I’m thinking; but Extras is the BBC, so, “Maybe it’s fine?”

But the thing is, we got commissioned in-house at the BBC. If Nira Park had done it [Edgar Wright’s producer] or if we’d gone with Baby Cow [Steve Coogan’s production company] or if we’d at least had a producer between us and them fighting for our vision, it would have been different. But when push came to shove, the same people who said, “We don’t want it to look like Doctor Who,” went and hired an award-winning Doctor Who director.

And he’s great. I’m always at pains to say that. Not because I’m trying to be diplomatic ...

I don’t think it’s a bad show. I just don’t think it’s Phoo Action.

No. The reason I put the script and the boards in the book is because, while it’s not quite Phoo Action, it’s still more Phoo Action than what actually got made. I wanted people to be able to read it, see the storyboards, and picture something different. Obviously, it’s the 54th draft or whatever, after going over it again and again and again, but at least it gives a sense of what it could have been.

The BBC3 Pilot script cover and storyboard detail. Art by Glyn Dillon. From Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.

The BBC3 Pilot script cover and storyboard detail. Art by Glyn Dillon. From Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.Were you giving up ground in every revision?

Yeah, when the series finally got cancelled, they took me out to dinner and said, “If it’s any consolation, you were right.” And I just said, point blank, “It’s not.”

At that point, the only consolation was that the series hadn’t gone ahead and been even more wrecked. It had taken so long to get made, and it had been such a fight for all the reasons I’ve told you. It took a long time to get to the point where the BBC fucked it. By this point, it’s 2008, a full decade after Jamie and I first agreed to do it, and already eight years after Gorillaz took off.

There’s this old saying, alright, I’m going to quote a knobhead here, I’m going to quote Morrissey: “You Just Haven’t Earned It Yet, Baby.” And honestly, that’s so true in the U.K.

I remember going to the U.S. for the Tank Girl premiere. There was all this excitement around us. An executive from Hanna-Barbera came up and said, “Come and have a meeting, we’d love to hear what ideas you’ve got,” just because I was part of the team. In the U.K, if you turned up to that same party, they’d kick you out. The establishment here didn’t want to hear your ideas.

And it wasn’t like Hanna-Barbera actually wanted to do something good. We were like, “Yeah, if this was ‘70s Hanna-Barbera, maybe we’d be interested.” But it was hard for me to get in anywhere. I’d been pitching Phoo Action for years, pitched it with Rachel Talalay, even had a development deal offered from ITV Studios when they were working with the Red Dwarf production company.

Maybe that would’ve been the right version of it. But honestly, I just don’t think British terrestrial TV at the time could’ve pulled it off. And then when Kick-Ass came out? I was like that Leonardo DiCaprio Once Upon a Time in Hollywood meme, pointing at the screen. We’d already told them: Look at Kung Fu Hustle. Look at the Beastie Boys’ "Body Movin'" and "Intergalactic." We spelled it out. But they just didn’t get it.

It reminds me of Scott Pilgrim vs. The World in a way where it had to be so far removed from the norm to be true to the source material.

There you go. That’s Edgar being able to stay true to himself, calling the shots. But he had Nira backing him, and of course Jess [Stevenson] and Simon [Pegg].

We’re going back again, but I just didn’t have that self-confidence at the time. Who was I to say no? I’d been trying to get this done for so long. Who was I to turn down a BBC deal? Whereas now, after everything, I know that just because a deal is offered doesn’t mean you should take it. That whole experience shaped my mindset when I finally decided, “If I’m going to do this book, it has to be the Phoo Action book I believe in, mine and Jamie’s, or nothing.” Whether that’s good or bad ... that’s up to everyone else.

There’s this old ’80s Swiss dance band, Yello, same era as Kraftwerk, but not as great. Kind of a cross between Sparks and Kraftwerk. Dieter Meyer, one of the members, said something that stuck with me: “When you’re making art, there’s always compromise. You can’t avoid that. But there’s no point compromising your vision to do what other people want, because if it fails, you’ll blame them. And if it works, they’ll take the credit. You have to succeed or fail on your own terms.” And that’s exactly it.

When people ask about Gorillaz, they’ll say, “Did you think it was going to be a big success?” Well, no, we didn’t have a fucking crystal ball. We just thought we were doing the right things.

The last time I saw Damon was ages ago, back when they first got back together and did that big showcase in 2017. I was at the Humanz party after that gig and I bumped into him. He gave me this massive hug and said, “You were part of this, part of the foundation. Can you believe how big it’s become?” And I just said, “This is what we always thought it could be.”

That’s the thing: anything can fail. There’s incredible art just left by the side of the road, dying for one reason or another. With the book, I just did what I believed in. The fact that I was reading Extras at the time of making the pilot with the BBC and doubting what was happening. That should’ve told me something. But I didn’t listen to my gut. I let my head take over. “It’s the BBC. You’ve got a deal. You’re doing a show. You should be happy. You’re in a privileged position. How many people would kill for this?” And so I went along with it.

But really, you can’t just let them fucking take over.

Because it doesn’t fit your material.

And because it was such a personal vision. That’s the mark of stand-out creativity. It has to come from a real place, not be watered down to fit some pre-approved mold. And our material’s fucking edgy. It was always meant to be. That’s what made it Phoo Action. You take that edge away, you smooth it out to make it more palatable, and suddenly, it’s just not the thing anymore. It loses its teeth.

In the book, you have character designs that really change from the early material. You have Get the Freebies which is almost pure gonzo, but then the actual TV series vision is way darker than how the pilot turned out with the character designs more apocalyptic and dystopian. You have these really creepy, horrific characters too. In looking at the designs and looking at the TV show, they couldn’t be more different. What did you imagine the TV show to be like?

The Uber Model and Jian Shi. Art by Jamie Hewlett, from Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.

The Uber Model and Jian Shi. Art by Jamie Hewlett, from Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.The TV series was leaning more into the Li Long Chang story, the antagonist we’d created for the cancelled Phoo Action comics. When you look at the prose story, which retells that arc, I feel like I’ve synthesized all of that. Even though I’m taking the story from ’97, I’m also bringing in that vision for what was meant to be the TV series.

At its core, it was a buddy cop comedy-drama, but with an ancient Chinese demon as the villain. Jamie and I were both massive horror heads, so we wanted to make this dark, comedic, still stupid, still Phoo series, but with that proper comedy-horror edge. Like Return of the Living Dead, “Tina! But I don’t care Darlin’, because I love you, and you’ve got to let me EAT YOUR BRAAAAAAAAAAAIIIIIIIIIIIINS!” We had those kinds of references baked in. In the pitch deck, we had pictures from Basket Case, and Jamie and I were both huge Mike Mignola fans, so that was another touchstone.

It was darker. The BBC had got scared by how cartoonish the Freebies were in the pilot. But the thing is, we purposely made them look like costumes. We wanted it to feel like the “Body Movin’” video by the Beastie Boys. We wanted that to be the joke. That you know there’s people in there and that’s funny. A bit shit, like League of Gentlemen, [The Mighty] Boosh, that kind of low-fi, knowingly ridiculous aesthetic.

But the BBC wanted it to be more serious. The concept art for the series also just followed where Jamie’s work was going at the time. If you look at the costume designs he did for Journey to the West, it’s right in line with that. The realization of that ended up more poppy, so who knows where it would’ve landed in the end on the series. We’ll never know.

I remember arguing with the producer. He was adamant you couldn’t do horror on TV, that even though HBO was making big, ongoing crime dramas, the BBC couldn’t do that kind of storytelling. And then, of course, they replaced Phoo with a show about ghosts, werewolves, and vampires – and that same producer went on to commission Peaky Blinders. Make of that what you will. The irony is, we’d actually hired a lead director who’d made a cult zombie movie, Outpost, about Nazi zombies, and his cinematographer was using Natural Born Killers as a reference. So there was hope. But at the same time, there was tons of BBC fuckery going on. So, who knows?

Back to the book. This has a whole new prose novel part of it. What were some challenges from adapting a story from one medium to another?

Well, it’s not just switching from one medium to another, it’s switching back to my 26-year-old brain. That was the first big question: “Can I legitimately do this?” In 2025, can a middle-aged white man legitimately write a story with an 18-year-old party-head junkie female lead and an Asian gay man, but who’s also a bit of a stereotype? Because Jamie does this thing where he creates characters that have some stereotypical traits and then flips them, but there’s definitely some late ’90s cultural bias and blindness in there with Terry.

So that was the first challenge. Can I find this voice again? But also, do I even want to? Plus, remember, I used to fuck with things just for the sake of it. I don’t want to be that same idiot writing without awareness, like I did for Penthouse. Another thing. In the interim, I actually trained as a sex coach, so I’m really aware now of all the unconscious attitudes towards sexuality flying around in the original material. That was another big thing for me. I wanted to reframe it, to make good on it, but without being heavy-handed. It still had to feel true to the characters and the property. I wasn’t interested in sanitizing it or turning it into something it wasn’t, but I was interested in making sure it wasn’t just replicating old biases without thinking. So I sat down and went back to the comics, with the prose novel and our old story treatment in mind, asking myself, “What do I actually want to resolve from this world?” What got left on the cutting room floor? The dynamics, the relationships, what was pushed aside while Jamie was barreling forward with three or four pages a month of satirical cartooning mayhem?

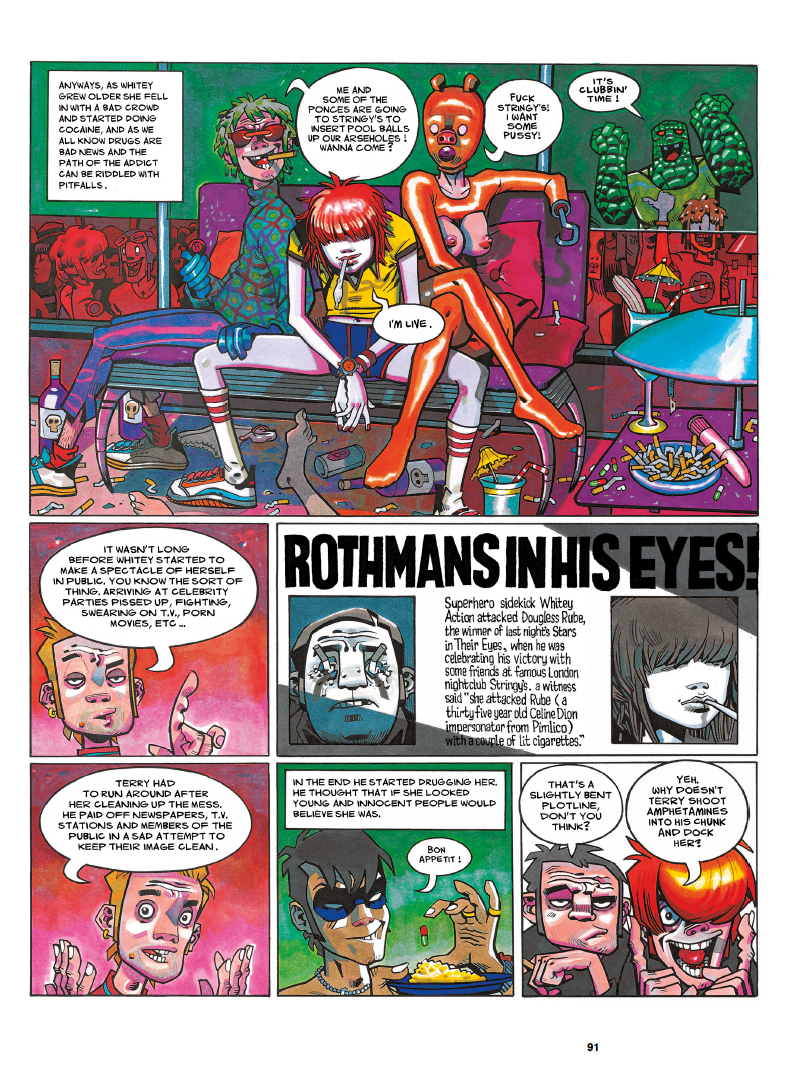

And then there’s this thing, just in the first episode of Get the Freebies, he’s got Terry putting Whitey on hormone retardants. She’s 16, and he’s drugging her with hormone blockers. And I thought, “Right, if I’m doing this book, I have to tackle that head-on.” Because, to use the word of the day, it’s problematic.

Get the Freebies, Ep. 1, by Jamie Hewlett. from Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.

Get the Freebies, Ep. 1, by Jamie Hewlett. from Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.And then there’s the bigger ideas: The Freebies coming back, dying, being reborn. And there are other threads too. Terry’s homosexuality, for example, is handled in this really deft way in the comics. There are these beautiful, quiet moments like Whitey going out for the night, and Terry’s just staying in with his flatulent boyfriend. It’s never a thing. It’s not played solely for laughs or shock, it just is, and it feels domestic and real. Jamie was so good at that.

But I wanted to build on it. What does that actually mean? Terry is an openly gay hero in London. What does that mean? And he’s Asian. We say Giles is his boyfriend, but we know fuck all about him. And Whitey’s boyfriend? He’s literally in one panel in the first episode, never named. You only know it’s her boyfriend because she’s in bed with him, skinning up with a blue Ben Grimm. And so I was just like, “Oh. Okay, I need to look at that.”

That’s what was so great about it. If you look at how Jamie handles interiority in the comics, it’s all visual: no exposition, just expression. Like, look at this panel. [Holds up Phoo Action page]

Panel from Get the Freebies, Episode 4 by Jamie Hewlett. From Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.

Panel from Get the Freebies, Episode 4 by Jamie Hewlett. From Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.You see Whitey looking through the Phoomobile window. There’s no dialogue, but what the fuck is going on in her head? She looks wrecked. She’s a kid, but she’s a pop star, a celebrity crime fighter, a superhero in a world where she’s also a junkie and an orphan. And everyone’s excited to see her because she’s all over the kids’ magazines and the tabloids. So I had to ask, what is that world?

I wrote the prose novel in three months because I wanted to work in the same style as we wrote the comics. God, am I going to sound like a pompous idiot. ... Anyway, one of Jack Kerouac’s maxims was “First thought, best thought.” Just write it down. Everyone talks about the first draft being a vomit draft, and yeah, you come back and edit, but the key is to get it out, to keep pushing forward. Like we would’ve done back in Jamie’s home studio in Worthing.

And it had already taken a year just to do the deal on the book, leaving me three months to write and design the whole thing under the original Z2 deadline. So I just wrote — start to finish, no looking back. Honoring that gonzo style we’ve been talking about.

Once I finished a first pass chapter, I’d send it straight to my story editors, James Harvey, a British comic book artist, and his partner Penelope Root. Then I’d dive into the next chapter while they did an editorial pass. They’d send it back, and my first reaction was always, “What the fuck have you done to my writing?” Then we’d get on a Discord call, argue it out. The first time they sent me edits, I just changed it all back and sent it straight back to them. But then I realized this isn’t going to work. We didn’t have the time for endless back-and-forths.

That’s when James sent me this Cinderella gif of two fairy godmothers zapping each other. It cracked me up. And that’s when I knew I’d found the right collaborative partners.

So we got on a call and had a proper editorial, story discussion. And by this point in my career, I’d worked my way up in the film industry, and had all the ups and downs we’ve discussed. After being a music video director and messing around with that, then being in Gorillaz and on to the BBC fiasco. That said, one of the best things about working at the BBC was that I basically got a three-year internship in development. I was around people who were working on scripts day in, day out on daily TV shows. So I got schooled. I knew what development was. After that I’d been working in film finance, development, and production for a decade. I had learned what works and what doesn’t work and I don’t have to think about it or second guess myself too much.

So, this a long way to say; I’d been in story development meetings a lot. I wasn’t coming into this book thinking, “It’s mine, it’s my words, no one touches it.” But as you can probably tell, I’m also pretty clear about what I will and won’t let pass. I’ve been doing this long enough to know I’m not going to just roll over and say, “Well, if you say so.” I know where that ends.

At the same time, I know the best thing you can do is work with other brilliant creatives, people who want to make you look good. That’s how Pixar works, right? And looking back now, I realize Jamie was doing this with me when I was first hired to work on the original story with him and then later, on Gorillaz. He probably didn’t even realize that’s what he was doing, but that’s exactly what it was. Bringing me in because he knew how to get the best out of me.

For the prose novel, when you’re working with Philip, how did the process go? Were you doing rough layouts? Was he just given the whole script and chose what he wanted to do?

I wrote the novel first. I didn’t want to ask Philip to draw something and then realize later I had to change an important detail or scrap something completely. Even though I said I was writing it straight through, no looking back, I still gave myself that safety clause just in case there was some massive plot hole in my outline that meant I had to go back and rewrite something in the setup. That didn’t happen, I hasten to add. But I didn’t want him drawing something for “Enter the Flying Scotsman” only for me to reach “Two Become One” and go, “Oh fuck, I need to inject this earlier, and now it’s already drawn.”

So I waited until I’d finished writing, then had a chat with Philip via email. I asked him, “Do you just want to read it and choose what you want to draw? Or do you want me to tell you what to draw?” And Philip, being Philip, was like, “Oh, I don’t mind.”

What I ended up doing was, per chapter, giving him a selection of things he could illustrate. I pulled out visual references, so he had the text, plus more specifics for whatever part he was illustrating, and I wrote up a proper brief for each one: what people were wearing, who they were, the set and setting. And he wanted that too. I think he was really nervous because he was —

— stepping into Jamie’s shoes.

You’ve got to remember, even though he worked on Get the Freebies, he’s not credited. So it was really important to bring him into the limelight here because he did a lot on that.

At the same time, by the point I’m talking to him about it, he’s dropping in cold. But I’ve now re-lettered all the comics, I have written the chapter intros, I’m retouching artwork, I’ve written a 70,000-word prose novel. I’m deep in it. And he’s just like, “I’m not quite sure.” Which is fair enough. Jamie had asked for references of all the characters too for the big double page spread and cover he did for the book. It’s stuff neither of them have thought about for 25 years.

A Jamie Hewlett double-page spread for Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.

A Jamie Hewlett double-page spread for Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.So he’s asking me, “If you want them wearing anything specific, just tell me. Show me.” And yeah, I was really specific. I’m not comparing myself to Alan Moore — I’m not — but I know he writes very detailed action descriptions for his artists. And I get that, because I’m a visual artist too. I come from film. I know what I’m thinking of. I visualize what I’m writing. I’d written the book with a really clear sense of the world, and even though it’s silly, it’s also very precise. Very time and place specific to a mid-'00s London. So that’s how I wanted to help Philip, making sure everything was in alignment between text and image with enough room for him to do his magic. And he did!

Three months seems crazy to write a novel.

Well, it seems to be a recurring theme. The last thing I did on Gorillaz was a show called Charts of Darkness, which I wrote, directed, and edited, and it aired within three months. Cass Browne, who I co-wrote Charts of Darkness with and who later took over writing for Gorillaz, actually wrote Rise of the Ogre in three months as well.

I haven’t looked into it, but there’s got to be something about that timeframe. Like rock stars dying at 27, or the William Burroughs/Illuminatus! trilogy 23 enigma, or The Hitchhiker’s Guide [to the Galaxy] answer to “the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything” is 42. Shit like that.

Obviously, I already had the story outline. When I say I wrote it in three months, I mean the prose. I spent maybe another month before that going over what we had, looking at what was missing, what was problematic, what worked and what was weak and fixing the things we always knew needed attention.

There are whole chapters in there now that are completely mine, bridging gaps, adding new layers. There’s one that’s a pastiche of Speed, the Keanu Reeves and Sandra Bullock film, because that’s a very Worthing School of Comics, Big Underwear thing to do, throw in a film pastiche.

The Freebies weren’t originally part of this story either, but they’re just too iconic. I wanted to make sense of who they are and make them whole. And, like I’ve said, Terry and Whitey’s dynamic ... it’s dodgy as fuck in Get the Freebies. As well as their lovers, friends, accomplices. That all needed unpacking. Same with some of the other throwaway villains. It was all begging to be done properly, to actually do justice to what was there, the insanity of it all.

Character Personae of Phoo Action. Art by Phillip Bond. From Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.

Character Personae of Phoo Action. Art by Phillip Bond. From Phoo Action: Silver Jubilee.I want to talk about superheroes briefly. Whitey feels the most “super” character with the magical utility pants, but she’d be inconceivable in Marvel or DC. There’s just no way Whitey can exist there. Elanor and Bill stand in the superhero genre as well, but Whitey is our main character. How does a superhero fit in the British underground comic scene of the late '90s? Is Whitey the Britpop Wonder Woman?

Well, Whitey and Terry are both superheroes. Terry’s a street-level hero, like Iron Fist or Luke Cage. But in the UK, we’re naturally skeptical about supes. Superheroes are preposterous. They quite literally wouldn’t fly here. That’s why we’re always deconstructing them.

There’s that whole American tradition: big, vaudevillian, camp, larger than life. It works, but until I went to the States, I didn’t get it. I loved it, thought it was amazing, but it was the total antithesis of the small, grey reality we were still living in. We were still paying off World War II. I mean, it was brown. Everything was brown over here.

I remember going to the States for the Tank Girl shoot in the early ’90s, driving to set in this massive Ford Falcon, Guns N’ Roses on the radio. And I hated Guns N’ Roses. But there I was, middle of LA, and suddenly I went, “Oh yeah, I get it.” We also nearly got gang-banged in Compton in that car, but that’s another story.

Anyway, back to your question. Whitey actually has Captain America’s shield in the first couple of episodes of Get the Freebies. I don’t know if you clocked that in the comics. We even reference it in the prose. She had to give it back because Steve Rogers put a copyright suit against her. We said, “Steve Rogers, the miserable old git,” or something like that.