Rare Flavours

Rare Flavours

Writer: Ram V

Artist: Filipe Andrade

Letterer: Andworld Design

Publisher: Boom! Studios

Collects: Rare Flavours #1-6

Publication: August 2024

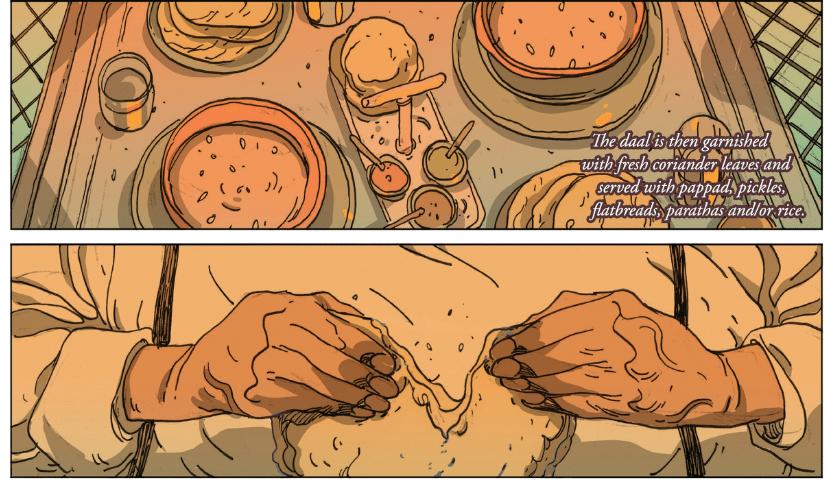

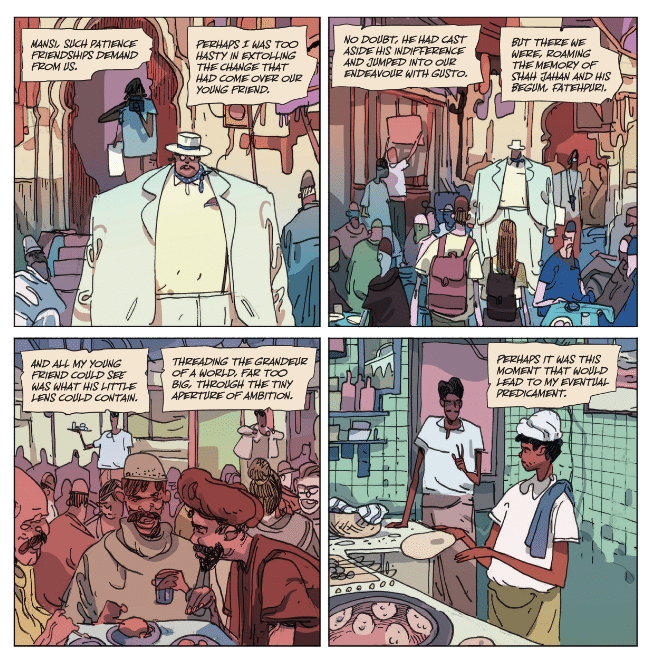

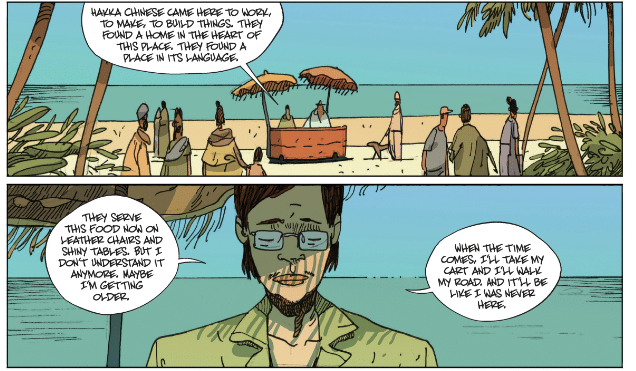

India is a culture of food. From the poorest slums to the largest cities, every area has a culinary identity composed of its geographical and economic history. Street food in particular is a staple of India that is so diverse that you could travel from one end of the country to the other and still find something new everyday. From pav bhaji in the streets of Mumbai to a finely crafted, sweet prasad in Delhi, Indian food is a labor of love from artisans that reflect their socio-economic background, religious ideology and family traditions. Like all human crafts, food is an art in both its culinary preparation by the artist and the judgment and appreciation of it by the audience. The art of food is co-constituted by this relationship that forces us to work at understanding each other. Sure, you can always just consume but the joy of it all is in tasting.

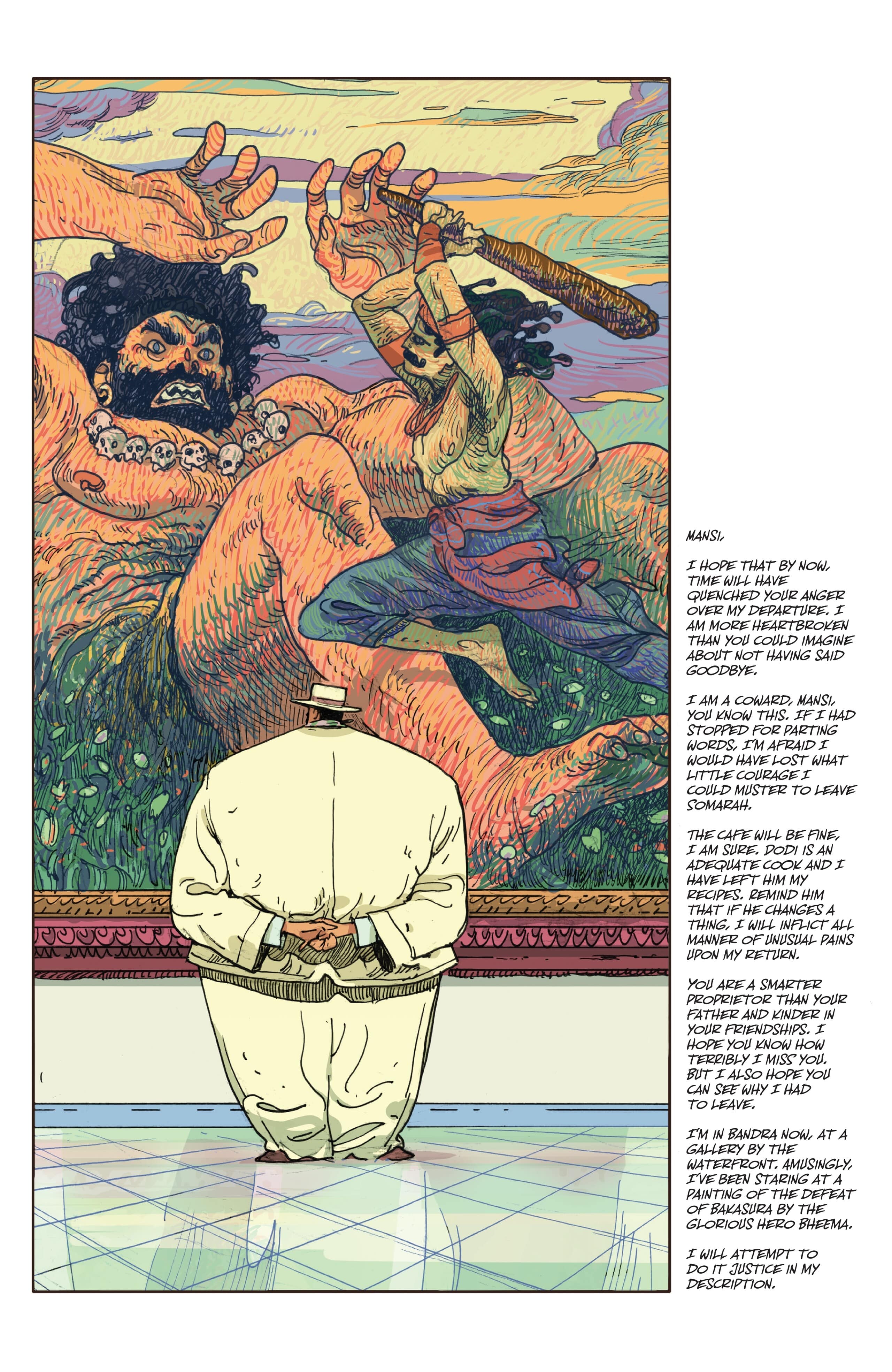

This love of food, and its expression as both a love of art and a eulogy to artisans whose craft has been crushed under the heel of capitalism is at the heart of Rare Flavours. The book reteams Ram V and Filipe Andrade who previously created one of the best comics of the decade in The Many Deaths of Laila Starr. Here they once again combine grand themes of humanity’s purpose with hindu mythology to take the reader on a journey through the various dishes of Indian cuisine. Their combined efforts creates one of the finest comics of the year, an aesthetically and emotional complex tapestry that helps us understand not only food, not only art, but the humanity inherent to acts of creation, and how, or if, that can be reconciled with an automated, industrialized world of destruction.

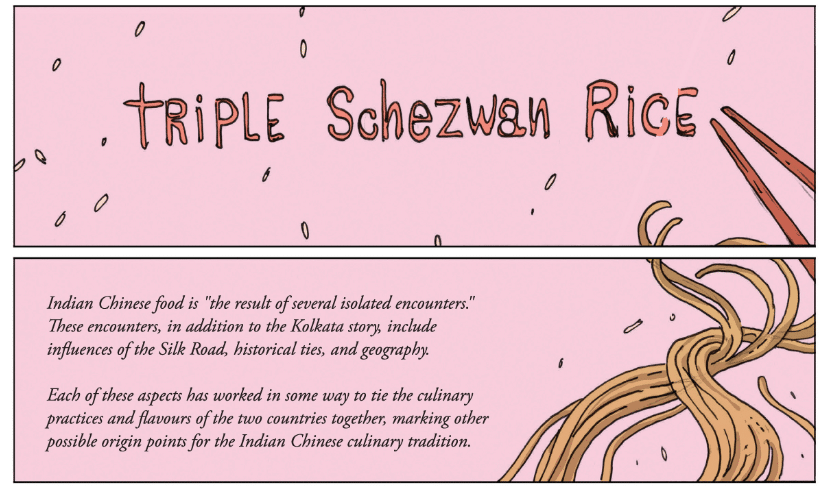

Rare Flavours follows Rubin Baksh (who is actually the forest dwelling demon Bakasura) as he convinces the human, Mohan, to help him make a documentary about Indian food. The pair travel across the country to find different stalls, food carts and restaurants. Rubin’s demon nature compels him to eat people, which ends up causing the pair to be pursued by the demon hunters Dilshan and Dilkush. Each issue is named for a specific dish, and the narrative alternates between Rubin’s journey and the recipe for the dish.

V and Andrade’s choice of structure forces the reader to not see the recipes as merely a list or steps, but rather a story in its own right. As an almost formalist exercise, the recipes are carefully spliced in between scenes so that we might begin to question the reasoning behind each ingredient and the history of the dish itself.

Essential to this choice is the lettering work of Andworld Design’s Deron Bennett. Each panel of recipes and ingredients balances an aesthetic between a cherished cookbook, and a storybook: bullet pointed and clear, but whimsical in its shapes that make the reader feel like they’re being told this sacred information with the same gravitas as magic.

To prepare a meal is to solve puzzles, to compose a unified whole that requires the cooperation and carefully measured influence of a variety of ingredients. The end result isn’t what matters, so much as the ability of the artist and audience to search for the meaning created by the connection between each individual piece. As we read through the steps, we’re allowed to stop and ask ourselves “how does this contribute to our final flavor? Where did each piece of the puzzle come from and how can I best arrange what I was given?”

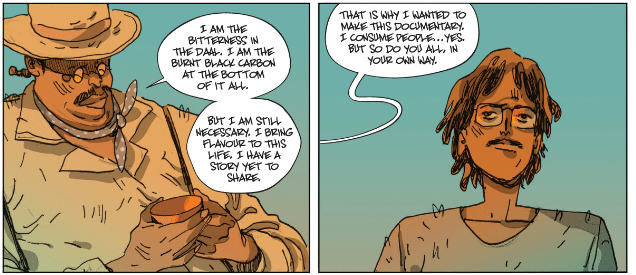

But an artist embarking on this journey must make some sacrifices and therefore Mohan has essentially entered a Faustian bargain, trading his soul for the pursuit of meaningful art. However, the negative connotation of this exchange is not where V and Andrade go. Rather, Rare Flavours is about the necessary sacrifice and labor inherent to acts of creation. Art is a reflection of our consciousness, and thus our pain, our history, our expectations are what pour into the work. Our lived experience and life is the flavor behind each dish, and as time goes on the work it takes to produce these meals becomes more and more difficult.

This concept contrasts with Ram V and Filipe Andrade’s previous collaboration, The Many Deaths of Laila Starr. Where Laila Starr was about a God, this is about a demon. Where one was about the essence of death, the other is about life. Laila Star begins in the bureaucratic, manicured prestige of Godhood that crashes down to reality, whereas Rare Flavours opens immediately opposed to that concept, with Rubin already fallen and without majesty.

The two books work together to tell a story about how we find our humanity, in all its mortal attachments and artistic expressions. Though with Rare Flavours, we’re left in a more ambiguous position, one that commands us to challenge how we live today and our relationship to art which has been reduced to mere content, something Rubin, for all his passion, is guilty of himself.

Rubin’s opening pitch to Mohan is to make this documentary and sell it to some giant streamer. His main goal is to put something out into the world that represents the complexity and richness of the flavors he’s experienced in his life. And yet, his choice of outlet is antithetical to this goal. Or as Mohan says, “Sometimes people don’t care about flavour… sometimes they just want to eat and move on.” That tension between the desire to create and the experience of creating plays out in Rubin and Mo’s relationship as they become increasingly frustrated with the abstract ideas that they are attempting to ground. Rubin early on laments his companion’s focus on the framing, on the technical without reference to the emotional content and goal of their work.

Rubin is the essence of what all good artists need: passion, experience in life, a perspective that is uniquely his that’s able to frame the world around him with intention. Yet, that skill comes at a cost. Like the streamer he wants to sell his documentary to, the act of capturing a culture that is meant to be lived into something that can be merely consumed runs the risk of destroying that which he wants to exalt.

Thus, Mohan’s innocence, his desire to tell a story that his mother would be proud of, is necessary to help us ground skills and knowledge of subject matter into something meaningful, something rooted in human connection and love. There is no art, whether that be food or film, without the consumption of something. All experience distilled down into story loses some level of its dimension, every chef’s work is predicated on the knowledge that their ingredients, skills and tools will someday lose their power. And yet, we do it all the same because love of art, making it and experiencing it, is how we stay alive, how we experience the meaning of our life and place in the world.

The arts thus run opposed to the consumptive nature of capital which takes all the ingredients and divorces the story behind the labor. Food carts and traditional methods of cooking lose more and more ground as the desire to mass produce overshadows the human stories we are all trying to tell; the love we put into our food that goes far beyond simple nourishment.

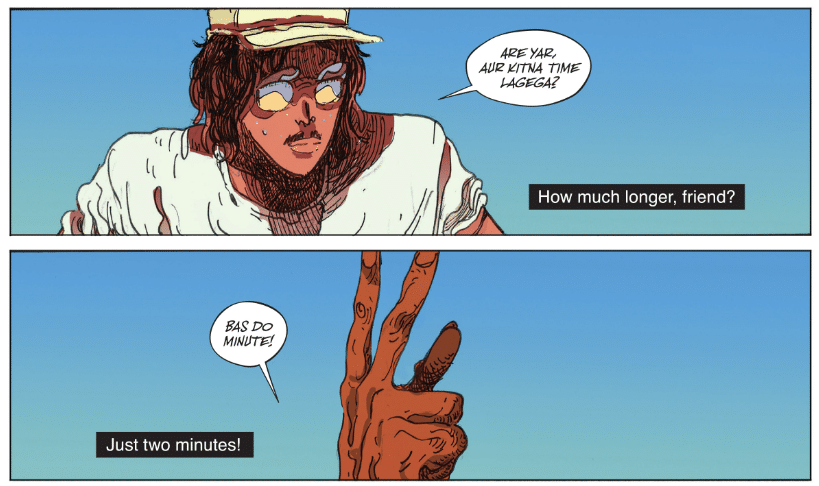

Once again, the lettering is essential here. Bennett does not resort to the typical signals of translation in western comics, like text between brackets and notes telling the reader “Translated from X language.” Instead, the hindi is written out at length, and the translation is presented like cinematic subtitles.

While it might seem like a minor touch, this added layer forces the reader to take the effort to experience the language, to say the words in the balloons and know that while they parallel the subtitles, they are distinct sentences. We arrive at the meaning of the words, but we like Rubin and Mohan are tourists here and are only able to loosely arrive at the meaning others embody.

Rubin and Mohan’s journey is one of bearing witness, of taking the life they’ve lived and transforming it into an art that others can connect with. And that consumption of emotional energy and desire to communicate does not have the ability to counteract that which was already consumed. Rather, it does its best to perverse what we can so that maybe the ghosts of our experiences might inspire others to question what’s on their plate. Maybe a flavor that is powerful enough can remind us that food is not just for subsistence and art is not just about consumption. Rather, it’s about the taste, the experience we have in the moment and that delight we spend the rest of our lives trying to recreate.

Check out The Beat’s reviews section for more great writing about comics!

English (US) ·

English (US) ·