Hagai Palevsky | December 20, 2024

The principle at the heart of Annie Baker's plays can most easily be described as the "communality born of circumstance." Most of Baker's plays are some variation on the following premise: A group of otherwise-unrelated strangers are brought together in a single purgatorial space; slowly, the exterior world melts away. When they leave the room, that whole world dies with them.

Sometimes, as is the case in Infinite Life, they are guests at a health resort; elsewhere, in The Flick and The Antipodes (my personal favorite, which you would know, if you cared about me), they are colleagues. The stage, to Baker, is static, stilted; set-pieces do not change. For the next two hours or so, she seems to tell her viewers, this room is all that exists in the world.

Not coincidentally, this is very much what it feels like to be at a comic convention: seven hours, or thereabouts, in a hall where time, casino-like, slips away, and the two most frequent questions you are asked — if you're me, at least — are "Hey, how are you doing?" (to which the answer is usually "Who's to say, man") and "Is that all you bought so far?" (to which the answer is "No, I got three more bags full, I just put them behind a friend's table, I have a problem, I know"). But, triumphant and physically burdened, I returned from England — the country so joyful that on Christmas of 2003 the #1 song on the charts was Gary Jules' godawful cover of Tears for Fears' "Mad World" — with several pounds of books purchased at this year's Thought Bubble Festival. I now intend to tell you about three of them. I hope that's okay with you.

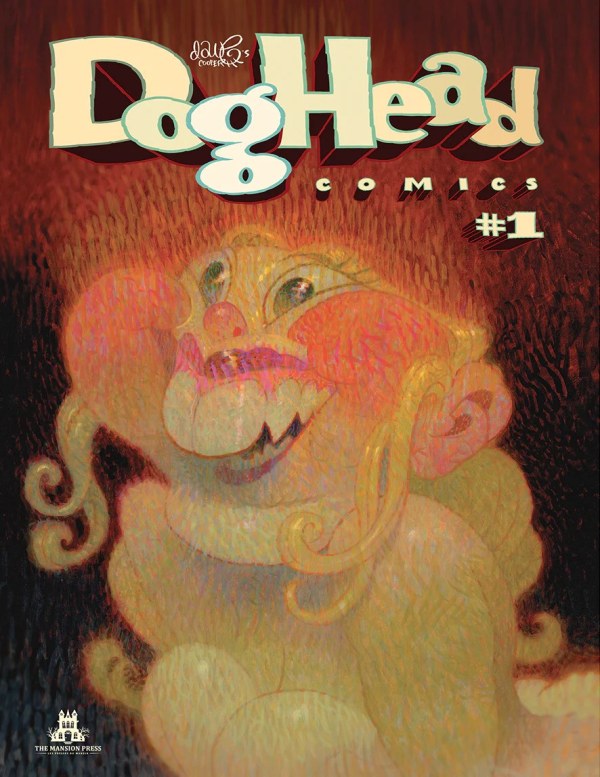

Jon Chandler's Dogbo, the latest release from London's Breakdown Press, purports to collect "all of its titular character's appearances." This is, in its own way, a misdirection, not because the riso-printed 32-pager is incomplete but because, in truth, there is no one Dogbo. Key to this comic is a total malleability of tone and character, more akin to Kevin Huizenga's portrayal of Glenn Ganges as "actor" rather than protagonist.

When Chandler goes for humor, it's the Jason Murphy type, pushing slapstick into emotional territories it isn't equipped for. In one comic, two guys try to force our canine-anthropomorphic protagonist, still alive, into a coffin, and a third man slips on a banana peel (left, one imagines, by Dogbo himself) – but this third guy is holding a pistol, and as he slips he accidentally pulls the trigger, the bullet going straight into the coffin. In another, set in a theme park, Dogbo tries to escape from the maddening crowd, climbing on a large egg. What happens next? "The visitors on the day of the big quake," the narrator tells us, "couldn't believe their luck."

By the time this well-trodden early-Hollywood-comedy motif appears in Dogbo, around halfway through the book, we know perfectly well that the crowd's luck is our man's lack thereof. Dogbo may be an anthropomorphic animal within a partly-human world, but his fate is more Elmer Fudd than Bugs Bunny: when he makes people laugh, it's not because of what he does – it's because of what is done to him.

In other comics, Dogbo isn't a dog at all. In one piece we are introduced to a different Dogbo – or, rather, an actor with dwarfism who portrays him. He is good enough at his job that his performance will live on in CGI, but not worthwhile enough to actually keep him on the payroll. Even his girlfriend ghosts him, for all the world to see. A Clowesian view of life: here's this guy, this figure of absolute whimsy, portrayed by a total sad-sack without a single ray of light to redeem his life. It's a complete derailment of the pre-established tone, yet it fits seamlessly. If the humor is one of humiliation, why should the drama be any different?

By the end of Dogbo, our hero has had enough. In the concluding short, he is part of a group of friends, though 'friends' appears only nominal; the leader of the group, Gibbo, treats the rest of them like subordinates, and when Dogbo — "Doggie," here — disappears they all go down to his house to try and find him, but to no avail. It's the way they talk about him (and to him, though he isn't there to hear) that proves him entirely right in escaping. Chandler portrays, in perfect detail, the point where a friendship is no longer based on love so much as on long-cemented patterns of abuse; their jokes don't seem playful, only mean-spirited in a casual enough way. In an epilogue, sixty years later, one member of the group thinks he sees Doggie on the street. The man appears oblivious, but maybe he's just faking it. Alive or dead, Doggie still haunts them – whether as a specter or shame or as a longing for an easy victim.

Like Dogbo, Chandler's style shifts and turns, from a cartoonish scrawl reminiscent of Brian Chippendale or Mat Brinkman in the more comedic stories to a flat, stiff, Ebisu-esque deadpan on the more sedate end. Form, here, deftly follows function, the cartoonist reinventing himself to reveal different emanations of the same fundament: No matter who or what you are, Chandler tells you,or how much the world around you should change, there's one thing you can count on: you'll always be the butt of the joke.

Lily Vie's self-published Dogbody, for its part, humbly dissents. One of several self-published comics at Thought Bubble that began in digital form as part of this year's ShortBox Comics Fair (Vie's second appearance in the virtual fair, after last year's House for Rent: Good Condition), Vie's cartooning is immediately appealing: her palette — rich, warm, subdued tones — is reminiscent of fellow UK small-presser Theo Plum; her lines and ink-work are crisp and uniformly weighted, occasionally calling to mind Linnea Sterte (a favorite cartoonist of mine, so I am immediately biased). Throughout the work there is a total control of graphic communication, not a line out of place, elevating Vie's layouts, both breathless (there are hardly any gutters between panels, one action cascading into the other) and ornate.

Vie's narrative follows a medieval-esque fantasy town whose veterinarian possesses the gift of speaking to animals. Living on the outskirts of town affords him the luxury of keeping to himself, only venturing into the human world when he needs groceries; otherwise, people come to him, and only with transactional requests entirely bereft of pretense – my calf won't eat, my horse has a limp. It's when he diverges from this well-cemented habit of isolation that our protagonist finds himself powerless. He finds a fair maiden to sleep with — one of the most visually striking pages in the book, as the cartoonist breaks away from the standard solidity of her objects and the two figures melt into one another, melt into pure Molly Mendoza-esque energy — and the next day he wakes up not only incapable of carrying out his duties but also unable to keep the voices of the human world, which he'd deftly ignored up until now, at bay. At once, he is beset by chatter and gossip, overpowering and really quite off-putting; at once, he is forced to speak to people, not in gesture but in voice.

Furious and helpless, the veterinarian attacks his would-be paramour in a tantrum (giving the people even more to gossip about) and runs away. He meets a wounded wild dog and begs, pleads for the dog to kill him and end his misery, but to no avail. Calming down somewhat, the two get to talking, and the veterinarian sees himself in the dog – no longer of use to society, a mangy old mutt. He understands what he must do: make amends with the girl and heal the dog, healing himself in the process.

Though the vessel that contains it appears perhaps simplistic (as far as communal connection goes, romance is a limited shorthand, as presumably even if we don't dislike most of the society around us we don't particularly wish to marry them), Vie's message is nonetheless a worthwhile one, if only because it doesn't seek a one-sided affirmation of implicit entitlement but a pointed critique: avoid the world all you want, but all that will do is ensure that your aversion becomes mutual. Much better, then, to embrace the connection that comes your way rather than reject it. Much better, indeed, to adapt. "Most of my fantasies," sings Bill Callahan, "are of / to be of use" – a perfectly beautiful sentiment, but one, fundamentally, bound to expire. By asking the logical next question — that is, what happens when you are no longer of use — Lily Vie pokes an elegant hole: Is that all, she asks, that you can dream of? Wouldn't you rather simply be present instead?

Allow me now to return to Annie Baker, this time in the context of cartoonist C A Strike's latest offering, Customer Service Eternity (another comic, in truth, from this year's ShortBox Comics Fair). Though structurally different from Baker's work—the cartoonist employs the tried-and-true Slacker formula of interconnected vignettes — there is nonetheless that feeling that the present space is all that there is, whether the present space is a café, a supermarket, or a vape shop.

If Lily Vie's cartooning is appealing for its neatness and solidity, Strike's appeal is the very opposite. This is a comic profoundly aware of its artifice, which largely works in its favor. The linework is pleasantly rocky (the figure work is particularly simplified and lumpy), faithful to "model" but not to any focused perspective; physicality will fish-eye and warble as the cartoonist strives for an overall tone of casual mock-histrionics.

Case in point: there's a sequence nearly halfway into the book, where the manager of one of the shops goes to buy a new vape cartridge at a store called Kingdom of Vape. The man knows what he wants (a sour apple cartridge, simple and straightforward), but the employee at the register — Annabel, though they have crowned themselves "The King" — is all too eager to recommend increasingly-contrived flavors (the final punchline is called the "Full English Breakfast," and its flavor profile, our cartoonist informs us, is "Toast (white) x2, sausage (vegan), tomato (fried), hash brown x 2, egg (fried) (not vegan), [and] baked beans"). It's a funny enough joke on its own, but it is elevated by cartooning tricks that call to mind Milton Glaser, or even Damion Scott: characters surrounded by simplified multi-layer haloes, backgrounds cluttering with warring textures. Strike's approach to comics is astute and immediately endearing. Under their pen, it is simultaneously a form of rhetoric and of representation; characters bring their own reality into life through sheer performance.

Yet there is a tension here, a circle the cartoonist can't seem to fully square. In one of the most charming sequences of the book (one of the peaks of Strike's approach to a Glaseresque montage), a character monologues about an excursion to the countryside (their first time out of the city in a very long while we are told); on the drive over they see some sheep, and though it is not their first time seeing sheep it sends them into a dissociative spiral over the intensity of their work-sleep-work cycle. From this monologue, the routine sounds grueling, the spiral justified. But the work itself, as portrayed in the comic, is exhausting only in comedic fashions: there's a customer you avoid, but at least you can joke about him; your colleagues are pleasant, and there's fairly little friction. There's a tendency toward coziness here, so as to keep from tonal whiplash, weighing down, slightly, an otherwise exceedingly charming piece of work.

Is the eight-hour workday a purgatory, like the landscapes of Annie Baker? Perhaps. But, under C A Strike's pen, maybe purgatory isn't so bad. Your friends are there, too, and if you're lucky you can even duck out to the next shop over and buy a vape cart that tastes like baked beans. And isn't that what life is all about?

English (US) ·

English (US) ·