Dan Nadel should be a name familiar to most Comics Journal readers. He is, after all, the former publisher of PictureBox, the author of such books as Art Out of Time, co-founder of the Comics Comics blog and — let's not forget — a former editor of The Comics Journal.

But now Nadel has wrapped up what might be his biggest challenge yet, penning a biography of none other than Robert Crumb, one of the most influential, talented and controversial cartoonists to ever wield a pen nib. Written with the artist's cooperation, in Crumb: A Cartoonist's Life, Nadel digs deep into the Zap Comics creator's history, offering new revelations about his family, milieu and paramours, as well as trenchant analysis of his art and what makes it worthwhile, even, as Nadel says, "at its most depraved." Refusing to dodge or excuse (at, it should be mentioned, Crumb's specific urging) the racist and misogynistic content that has drawn understandable anger over the decades, the book is a well-rounded, thoughtful portrait of the artist that I believe will be pored over and discussed for many years to come.

I spoke with Dan back in mid-January about the book, shortly after Trump's second inauguration and Jules Feiffer's passing, both of which we remarked on at various points. It was an enjoyable, insightful discussion, if occasionally rambling due to my own inability to stay on topic. Dan is a sharp, knowledgable guy and it was a lot of fun to talk about art and comics with him

Note that this interview has been edited for clarity by both myself and Nadel — Chris Mautner

CHRIS MAUTNER: I wanted to begin by asking you about your own personal journey with Crumb’s work. How did you first come across his comics? What was the first Crumb comic you read and what was it about that particular story or image that set you on this path, where now you're his official biographer?

DAN NADEL: [laughs] You’re starting light.

Oh, I'm jumping right in the pool here.

The first Crumb comic I remember seeing was American Splendor, and I think I even still have the book. Yeah, I do. It was the first American Splendor collection, and I got it at a comic book convention in Bethesda, Maryland, I believe.

Sequence from "A Fantasy," from the first issue of American Splendor. Written by Harvey Pekar, art by Robert Crumb.

Sequence from "A Fantasy," from the first issue of American Splendor. Written by Harvey Pekar, art by Robert Crumb.Pre-SPX I assume.

Oh, yeah. I was probably 12, so it would have been in ’88. My local comic book store growing up was Big Planet Comics. And at some point, as a young teenager or preteen they handed me Maus and of course it blew my mind. And I remember going to a convention and the dealer saying, “What are you interested in, kid?” And I said, “Oh, I like Maus.” And he handed me this American Splendor collection. Which I still have.

And it completely changed my life. I mean, there's strips in there that I memorized. And then the next thing I discovered was Head Comics, which was the Fireside reprint from the ‘80s, at a used bookstore and my dad bought it for me. Amazing, right? I must have been in 8th or 9th grade.

Was he aware of Crumb at the time? Did he know what he was buying you?

No idea, no. [laughs] And it was similar to the feeling I had many, many years later in the early 2000s, when I first saw Ron Rege’s comics or CF’s comics, Ben Jones' comics. It was like, “Oh, now I'm home. This makes sense.”

Partly because I was an alienated kid, but also because by then I had spent a huge amount of time in the Bethesda Public Library, reading the handful of histories of comics, the Smithsonian Books. The late, great Jules Feiffer's book. But really, those two Smithsonian books were the thing for me. I think there were some Ron Goulart books there.

There was a small host of coffee table books at that time. I remember there's one I've been trying to track down that had a vague, breezy history of comic books. I think that's how I first learned about EC.

I always tell the story of how my library in Bergen County, New Jersey, had The Celebrated Cases of Dick Tracy. I had a banana-seat bicycle and I would just take that book and balance it on my handlebars. I was constantly taking that book home.

I begged my mom to buy me the Smithsonian book. We got a flyer about it in the mail, and I was like, “You have to get me this.” And bless her heart, she did.

Awesome.

So by the time I got to Crumb, I was primed with the history of comics and it just made sense. It didn't mean I stopped reading everything else or it was a moment of conversion. I still deep into the X-Men and Chris Claremont. But this just resonated with me and I wound up, unbeknownst to my parents, spending most of my my Bar mitzvah money, which was like maybe $700 or something, forging a signature that I was 18 and buying underground comics from a mailing list from Don Donahue, Bob Sidebottom and the Bud Plant catalog.

Wow.

So I’m getting Zap and all this stuff coming to the house. [laughter] I don't know what I was thinking. I don't really know what I made of it all at the time, but I just needed to have it.

And then, like everybody else of our generation, I discovered Hate and Eightball and Love and Rockets. And once you're on that track, as you know, it just reinforces itself. And then you discover the Comics Journal and you start reading interviews …

And then all hope is gone.

[laughter] Yeah, all hope is gone.You briefly engage with Cerebus, then you go away, then you come back. [laughter]

And you think “I don’t want to read all these text pieces” and then you do.

Then 25 years later, you read his collected letters. You know, it's a mess. It's a disaster.

You talk about that feeling of being at home. Is there anything about Crumb in particular that stood out above the other work that you were seeing at that time? And if so, did you know at the time what that something was?

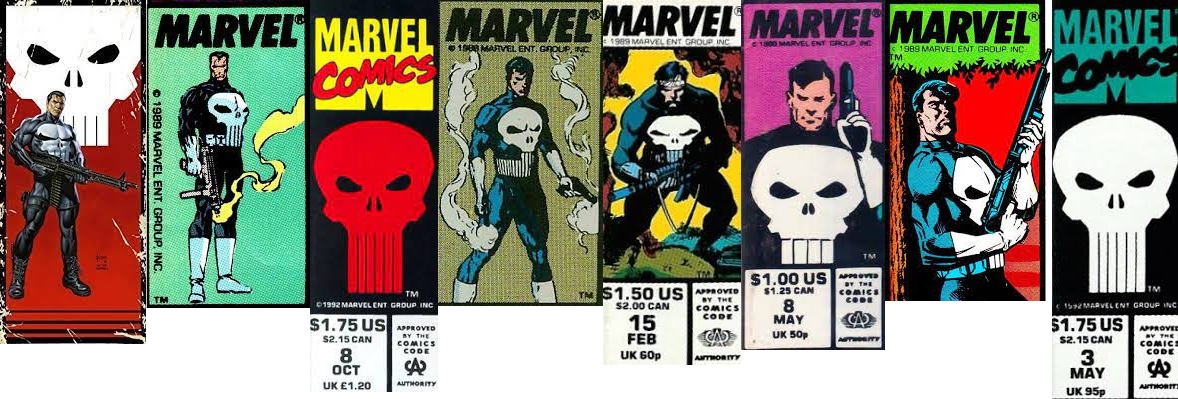

Good question. You know, the thing about Crumb is it's articulate. He's articulate in his comics. They are profoundly articulate, thoughtful comics. Even when they're at their at most depraved, they’re still ingenious in a way. I think I was probably responding to the incredibly varied ideas at work, combined with a really strong sense of craft. And craft in every sense of the word: storytelling mechanics, draftsmanship, lettering, the whole package. And I don't think I'd seen anything like that in visual culture at that time. You're growing up, you go to the pharmacy, you get Mike Zeck's Punisher, but this was something different.

But I knew this was a whole other thing. And the thoroughness of it, the completeness of the vision was really, really compelling for me. My criteria is still a complete vision executed with care and with real thoroughness and intentionality. It’s still the thing I respond to most in art in general. There are very few cartoonists who achieve that level of synthesis, to have both the complete vision and so much to say. You can count them on one hand. It's so unusual.

Was that what made you decide to approach him and ask him about doing his biography? What flipped that switch from what you're talking about to being like, “I need to write his story.”

You know, I was desperately trying to get on Comic Books are Burning in Hell and nobody would respond. [laughter]

I'm desperately trying to get on there too.

I just wanted your approval. I wanted Tucker to like me.

No, it’s a few things. As you know, I did PictureBox. I'd done these compilations of comics, Art Out of Time, Art in Time. I had curated exhibitions, did the Comics Comics blog and edited The Comics Journal by that time. But because there's something wrong with me I still wanted to write more about comics. [laughter] Chris, I had more to say.

Sequence from "Dumb," 1994. Reprinted in Existential Comics.

Sequence from "Dumb," 1994. Reprinted in Existential Comics.There's always more to say.

Oh yes. So first, I wanted to keep writing about comics. Second, as you all know, there are very few venues that offer any payment of any real kind for us middle-aged humans to live on, particularly in Brooklyn, N.Y.

When I started thinking about the project, there had been a recent spate of biographies of cartoonists like the Schulz book, the Tisserand Krazy Kat book. My all-time favorite prose books about comics, Michael Barrier's Funny Books is a group biography of Barks, Stanley and Walt Kelly, as as the story of Dell. It’s compelling and just lived in. And I feel like writing about comics needs that kind of lived-in quality, where you're writing about it almost from the inside.

I was looking at the shelf of books I had and thinking a lot about [how] this is such a great way to explore the history of the medium. You write a biography of a person and it expands out into their world—you can do a lot.And aside from the film, I was amazed that there wasn't one of Crumb. I had been thinking a lot about Crumbbecause Sammy Harkham and Ronnie Bronstein had been working for awhile on R. Crumb’s Dream Diary.

. It came to me as a slightly abstract idea and then I thought, well, why? And the why is essentially you can tell the story of 20th century cartooning through him. In a much longer book, I could go into much greater, snoozy detail. But in this book, I feel like you can read a huge amount of that history into him and then a huge amount of the contemporary history of comics and art out of him. That was enormously appealing to me 'cause I wasn't sure at that point – and this is like 2016 or 2017 – I wasn't sure if I knew how to write a biography, despite being an avid reader of them for years and years. But I knew that I could write about the ideas, the business, the milieu of 20th century cartooning, and I knew I could write about what came after. I knew that I could write a bit about Clowes or Panter or Groening or whatever.

So I just thought,I just have to do it. It was the only thing I could think of that met the criteria that I usually apply to projects, which is: does this fill a gap? Has this been done? Is it gonna maintain my interest? And so I just had to do it. Like with the other things I've done in comics, it just felt like this had to exist.

And if it's not me, it's gonna be somebody else and I didn't want it to be somebody else. I wanted to do it. I mean, the very first thing I tried to write for the Ganzfeld, way back in ’99. was about Mystic Funnies. So that had been on my mind for a very long time.

So anyway, that's a very longwinded way of saying I had this idea and I wrote to Crumb and six months passed and he wrote back and said “Well, if you're serious, why don't you come to France and we'll talk about it?” A month later my wife Elisa and I flew to Paris and took a train down to Robert and stayed with him for three nights.

And, you know on the second day we were there, the next morning, I was just wracked with anxiety and I said, “Robert, are we doing this or not? Come on. You’re killing me.” And he said “Ok, ok.” And then he imposed these conditions.

You start off the book with that, you talk about how he was very concerned about making sure it wasn't a hagiography.

Yeah.

Opening page from "Patton," reprinted in Existential Comics.

Opening page from "Patton," reprinted in Existential Comics.And I think people who are familiar with Crumb would be like, well, yeah, of course. But I think people who aren't familiar, who might be coming to this book cold, would be surprised by that just because most people would say, “Well, just don't make me look too bad. Ha, ha.” They wouldn't insist that you mention all the ugly stuff about their work and their relationships. … More of a statement than a question [Nadel laughs]

He is somebody who is keenly aware of his legacy and he's been archiving himself since he was eight or nine years old. By the time he's in his mid 20s he's giving interviews about what underground comics are as a medium and what he's doing and how he's doing it and what it means. But on the other hand, there are strips that really show him at his absolute most depraved or offensive.

So there's always this understanding that he's doing something unprecedented in the medium, but also the need to show himself in the worst possible light. He won’t allow one without the other, really. And it’s because he

in pursuit of truth and unvarnished honesty. He wants just to be honest, at all costs. It took me a while to realize this. Actually longer than it should have, because I'm so used to being the interviewer, but part of the relationship with him was me telling him things to show that I was honest too. Which is reasonable, he's giving me a lot and I'm just sitting there like, “Mmm hm, mmm hm.” So that was important.

When you say telling him things, you mean telling him personal things about yourself?

Yeah. Relating to things in a way that's not just me as the silent biographer. This will sound more cynical than it is, but he is aware that a hagiography would not serve his legacy. Because then the story's dismissible. And it's a great story and by making it warts and all it makes it true and relatable, and also I think, you can't just say, “he was an asshole, the end.” Not to excuse anything.

No, I don't think you do in the book. But there's two things you mention early on [in the book] that I thought were interesting that I hadn't really considered before. One is your description of him as this guy who constantly feels the need to self flagellate, to debase himself on the page, to the point where it goes almost beyond honesty to a need — I mean the cheap psychological take would be, “Oh, he’s got a Catholic martyr complex.” But you harp a couple times in the book on this need to really debase himself almost to the point where — and I'm gonna circle back around to this again — but there's a question of how true the incidents he portraying are when he's doing autobiographical comics because he's deliberately putting himself in such a negative light.

I think Robert is … he's a yarn spinner. So he's gonna tell the story that intrigues him the most. And he's also somebody who builds up a huge amount of steam and then is in a fury. If you read his letters on a topic that really pricks at him, you start to see him kind of fulminating and getting more and more into it and he can't stop and he's getting angrier and angrier or more and more excited. You see it about records or his conspiracy theories, for example.But the comics are a bit like that where I get the sense that he is so into something that he's following it down the road and that road might deviate from the facts. And for all his brilliance, like I say in the book, he doesn't always imagine what the other people are thinking.

No, And that's a criticism I sometimes have of [his work], especially when he's on a tangent about a particular topic like "Where Has It Gone, the Music of Our Forefathers." I feel like that's one of his weakest stories 'cause he doesn't consider that not everyone shares his opinion, the idea that, say, Robert Johnson wouldn't pick up an electric guitar if he had the opportunity to do so.

Yeah, exactly. It's a funny thing.It's a very particular mentality that we've all encountered. It's someone who spent a huge amount of time cultivating themselves. And to the extent that it may not be this way in everyday life, but when it comes down to putting pen to paper, they don't allow for a whole other way of thinking. Just a whole other perspective on life, like, “Hey, you know, I really like Neil Young.”

I don't mind listening to Bruce Springsteen every now and then.

Yeah. And I also like Charlie Patton. These two things are not incompatible.

But Robert, you know, is somebody who formed an identity entirely from the ground up. He is a creature who has invented himself in a way that was entirely based around things he was into and things he could make. That kind of identity and that kind of dedication doesn't always allow for other points of view to come in, and it does come out in stories like "Where Has It Gone," which I agree is one of his weakest stories.

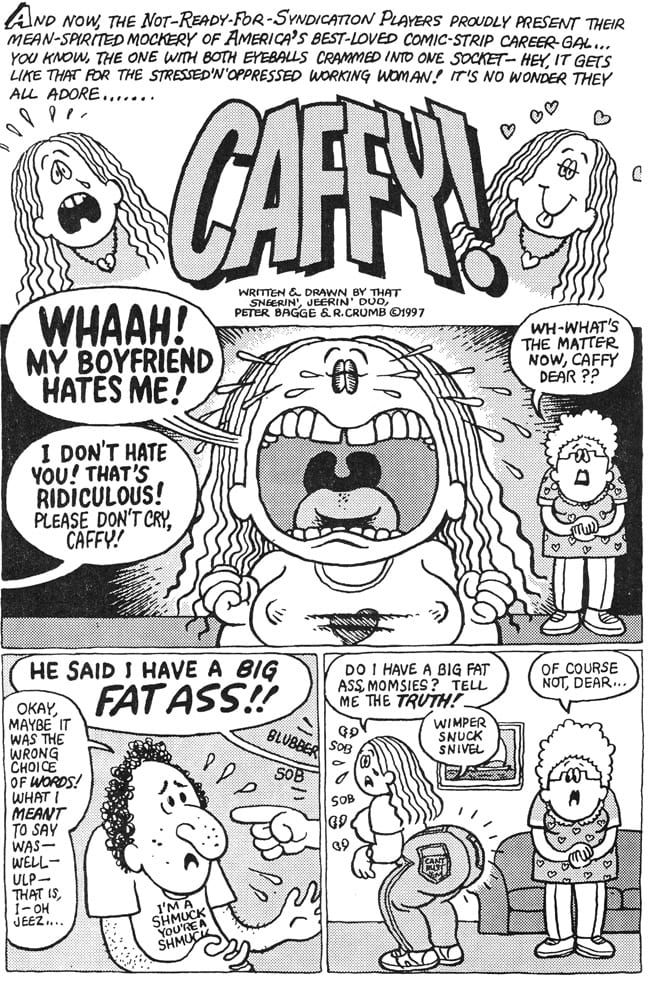

And there are other things like that where you just think “Alright, OK. I get it, but really?” But it was something that he needed to get off his chest. That’s aspect of him that I think is compelling as an artist. He'll do things like the Caffey story that he did with Peter Bagge or the Omaha parody, where you just think, “Why?” Because he just need to. He thinks through drawing. That’s the thing. He thinks it out on the page.

I think you're absolutely right. One of the things I've always found fascinating with him is that sense of compulsion, that I must get this down no matter what, and it doesn't matter how it affects me, my reputation, I must put this down.

Yeah.

Because most people, even artists, don’t necessarily have that that drive.

But circling back to what we were saying before about the issue of honesty. One of the huge revelations to me reading the book was [about] one of his most infamous stories, "Memories Are Made of This," where he portrays himself date raping someone. And you actually interviewed the woman in the story who says that's not true, that never happened, it wasn't like that at all. That seems like the primary exhibit A of him being the yarn spinner, debasing himself for the sake of the story versus portraying the actual incident.

I think it's fascinating. There are two things here. One is he loves to portray himself as the creep. You see it in those photo funnies. He loves that idea that he is the creep, that he's lecherous. And listen, he can be creepy. That’s real. But to go that far … I think it's the "tempting fate" thing. Given what happened on Monday [Donald Trump's inauguration], what was inaugurated on Monday, his warnings are very prescient. He is showing the male drive to power and domination and warning us, I think. I think that's the most generous read of it.

The less generous read is he is depicting violence against women for entertainment. I don't think that's what it is. Why he would do that, draw that story? It's the way he speaks as well. He is going over these stories in his mind, these memories and thinking about the lengths to which he would go for a record or for sex … really records and sex. And except in the case of of a couple of partners, it's always been very difficult for him to imagine a woman being as empowered by his kinks as he is. One of the very first interviews I did for the book was Lark Clark, who is is the woman he meets in in the late 1960s and has the affair with. Lark gave gave me this amazing interview where she was talking about how she really fell for him. She was this incredibly interesting woman in New York in the ‘60s who ran with the Fugs and the Holy Modal Rounders and was this sort of "it girl" of Lower East Side Bohemia. And Crumb’s whole rap was, “Well, she was only interested in me 'cause I was famous and blah blah blah.” And she said, “Yeah, that's how we met ‘cause he was famous, but then I was completely taken with how kind and lovely he was, and how thoughtful and blah blah blah.” And he couldn't imagine that. He couldn't imagine that a woman would fall for him on her own terms. Maybe I'm getting off track, but the self hatred, his own internal self-hatred is so strong that he can't see how a woman would have similar kinks to him, or even like him as a human being.

Susan Stern, Spain’s widow, said to me, “God, who on Earth is still hung up on being rejected by girls in high school? Like what is the deal?” And I wrote that to Robert and he was like, “I am.” I said, “Well, OK, but that's not the point. The point is you can't go through life with that as your prism, your lens on life. Now, of course, as it turns out, the world is now being run by men who hate women.

Page from "Memories Are Made of This," which originally ran in Weirdo #22, 1988.

Page from "Memories Are Made of This," which originally ran in Weirdo #22, 1988.Right. Deep seated resentments. The Rough, Tough Cream Puffs are in charge.

It also puts something else in my mind when I was rereading some of his comics, which goes along with what you're saying, which is that he frequently criticizes women being drawn to powerful, handsome men, but never acknowledges his own attraction to attractive, powerful women. Like he sees some kind of weird binary where it's really just this universal thing. He talks about it in the Crumb documentary too, where he's at a party and he mentions how women are attracted to powerful men. And I'm like, “You're attracted to powerful women.”

And also he's a powerful man. And he was powerful.

Yes. And he's personable. He's knowledgeable …

I can think of one other person I've met in my life who is as charismatic as Crumb. He is unbelievably charismatic. And if you talk to women like Lark Clark or lots of women who I spoke to [who knew him] in the ‘60s, they all say he was beautiful. He wasn't Jim Morrison. Fine. But he was poetic and had beautiful skin and was sweet and complicated. This was not the grotesque creep that he portrays himself as. He feels that way about himself. It's not a put on. He's in pain, but it's not necessarily how others saw him.

Sequence from "The Many Faces of R. Crumb," from XYZ Comics, 1972.

Sequence from "The Many Faces of R. Crumb," from XYZ Comics, 1972.Right. The other thing you talked about with Crumb early on, is this his mercurial nature, the idea that one minute wants to be left alone and the other he's charming and gregarious. And reading that called to mind the strip he did, “The Many Moods of R. Crumb” where he portrays this chameleon-like behavior. And I remember reading it at the time and thinking, "Oh, he's just exaggerating." But your book actually suggests, no, he's really got a chameleon aspect to himself that varies depending on his mood.

Yeah, he does. It's interesting. We meet people at all different stages, right? The Crumb I met in 2018 was warm and solicitous and kind and generous and talkative. Would he have been that way in 1998? Maybe not, but as he's told me, Robert has nothing left to prove. He did it. He survived. He's comfortable, he makes work, he does what he wants. That said, he allows himself to be – the kindest way to put it would be in the moment. Which is to say he'll say yes and if a stronger wind blows, he might say no.

Robert's not an operator, so he's not gonna sit there and negotiate the contract and he's not gonna go to the opening and glad hand and do all those things. But he will want what the contract offers. And he'll want attention whether he goes to the opening or not.

It all has to be on his terms. And he's also he's somebody who spent a huge amount of time cultivating an inner life. So he's focused on the kind of moment to moment existence. And I think he's probably always been that way. And had his priorities and a sense of survival.

I was gonna say that because we talked about his inner life, but he had to have that growing up in order to in order to get through childhood and adolescence.

Yeah. I mean, if he's mercurial, it's because. Robert needed to survive. His strongest instinct was to survive and make art.

Being mercurial, I think is a way of adapting to any given situation so that he can continue doing those things. I think that's a huge difference between him and other cartoonists of his generation and artists in general. He did not get hung up on various things that cartoonists or artists of all kinds get hung up on, nothing really slowed him down. And I think part of that is being mercurial, being able to say, “No, yes, maybe, I need to be quiet now.” He's doing these things to keep himself intact.

Tell me a bit about the research you did for the book. You say in your afterword how Crumb has this huge archive but I’m sure there were things you had to do beyond beyond that for the book.

Oh yeah. The archive was of course the baseline. I interviewed over 150 people.When I met with Robert and Aline together I had a list of who I thought I should interview. They added people to that list and as I got deeper and deeper, I'd find letters to people I'd never heard of or mentions of people I'd never heard of. And a chunk of his archive was also Charles’ letters, which have never been seen, which are fascinating and profound. And then his father's archive. You know, it's just like archive upon archive upon archive. I went through Robert's archive which includes a chunk of his late best friend Marty Pahls’ research for his introductions to the Complete Crumb volumes 1-3.

A few crucial interviews pointed me to deeper directions, like when I first met with Jay Kinney, he said, “You need to look at underground newspapers.” And I knew that I would have to in the back of my mind, but I didn't realize how important that context was. So then I spent a lot of time reading about the underground press in the 1960s and went through a handful of books about that and just going through those newspapers one by one, just seeing what the whole picture was. The Billy Ireland, of course, has Jay Lynch's papers and the Bergdoll brothers’ papers and Jay Kennedy's papers, all these troves, all these archives that helped me triangulate what was happening and when. Denis Kitchen’s archive at Columbia University was useful for that. A lot of this was thanks to these institutions that have maintained these archives and made them publicly accessible. The book wouldn't have been possible without Billy Ireland.

I knew there were certain areas that I didn't know that much about, underground newspapers being a big one. The politics of the Central Valley of California was another one. Just understanding what that was. I probably went way too deep into it for in my own research, given what came out, which was just a page.

The good news was that while I was writing this book, I was the curator at large for a museum at the University of California, Davis, which is just 20 minutes from where Crumb and Aline lived in the late 70s and 80s until they moved to France. So being there and being able to drive that land and go see Bob Armstrong and their friends who are still there, that was enormously important. Just seeing the land, understanding what the landscape was, going and visiting Crumb’s house, stuff like that. That kind of research was really invaluable

I was really trying to understand what it would have been like to be moving through those worlds during those times. Luckily Aline had corresponded with a friend of hers for many years, and that friend had kept that correspondence, and that helped me enormously understand who Aline was in the ‘70s and what was driving her and Robert, what was beneath the public character.

Robert buried me in paper. Even if you just spent time with all of his introductions and all of his interviews, and all of the sketchbooks, even if you just did that, it's A lot. Then you add in his own archive of unpublished material, and it was just thousands of pages.

So I had a lot of material. And then talking to other people and putting it all together. I found some really interesting rabbit holes, like Cleveland Bohemia. American Greetings. Chicago tabloid publishing. Each one of these worlds he passed through had a rich history. The trick was saying enough about it to make it interesting and understandable without bogging down the narrative. I had to keep the book moving. I knew what it could not be. It could not be a list of facts. It had to be a narrative. Otherwise it's just dead in the water.

From the original "Treasure Island Days" by Charles and Robert Crumb, reprinted in Vol. 1 of The Complete Crumb Comics.

From the original "Treasure Island Days" by Charles and Robert Crumb, reprinted in Vol. 1 of The Complete Crumb Comics.That was really interesting, that aspect, which is something that’s never really been discussed beyond, “Oh, he worked at American Greetings for a while.” And you got a lot of really fascinating info on that.

There are a lot of really amazing revelations in the book, I thought. Stuff where just like I was like, “Holy cow, I didn't know that.” Starting with the revelation about Crumb’s mom and the relationship she had with her stepbrother.

Yeah.

And all this [information] you have about her and her family and Charles Sr.’s family. How did you find all that?

Robert had a lot of that information. Some of it was in his archives. Some of it just came out through very careful questioning of him. I mean, our interviews lasted days. We were just talking and things would emerge and then I'd sort of press on certain areas.

For the in-depth detail about life in Philadelphia at that time with his mother and her stepbrother, I spent a lot of time on ancestry.com.

[laughs] I was wondering if that was it.

Oh yeah, it was a huge part of it.

I made contact with cousins who are adults now. I found them on ancestry.com. They were also doing research, and they were lovely and super interesting and helped fill in a lot about that world.

I found some other people who did not want to be named because the Crumb film freaked them out so much, but I found other family members who filled in detail. There were people I was never able to get to as I mentioned in the afterword. It's a very sad story. You know, I really felt for her and for them and it’s a terrible story. So sad.

Well, reading the book, one of my big takeaways of the biography is this idea of family trauma. Where you have these things happening to Crumb's mother, Crumb’s father going through the war, and that is visited upon the children. And then with Robert Crumb and his idea of protection, locking himself off in ways and being a person who goes along to get along, There was one point in the book where — I think it's a Kathy Goodell story — where he's hiding in a bush. And I just wanted to reach into the book and pull him out and be like, “What the hell are you doing? Show a spine.” And with Crumb's own children this idea of intergenerational trauma passing through a family. I'm not saying it's intentional or it came out about consciously, but does that does that jibe with you?

Yeah, it does. It was not intentional. It sort of happened. I went into the book knowing that there'd be a high body count emotionally and physically. And I knew that had to be reckoned with. I was surprised by how much trauma there is. There is a lot more detail about his father that I left out for space reasons. It was bogging down the front part of the book, but I got access to his military record and I learned all sorts of things. And, you know, the trauma of how Dana was brought up.

Yes.

The trauma of Robert being a terrible father to Jesse. These are things that just kept rolling. And I don't quite know that there's a big takeaway from it. … The takeaway is that for Robert – unique among these characters – not only it is he an artistic genius, but he has this incredible instinct for survival. And it's so rare amongst artists, you know, he could have destroyed himself a long time ago.

Page from "Walkin' the Streets," from Zap Comix #16. Reprinted in Existential Comics.

Page from "Walkin' the Streets," from Zap Comix #16. Reprinted in Existential Comics.Well he’s got that other side of the coin in Charles, someone who was talented and smart. And again, another revelation: I knew it was brought up in the Crumb documentary a little obliquely, but wasn't aware just how bad his homosexual and pedophilic tendencies were, and that was very sorrowful. Disturbing, but also very sad.

So sad. I mean, he’s such a sad character. There's a moment around when the film came out or after where people were like, “Well Charles was the real genius.” And that's just not true. The difference between Charles and Robert is that Robert needed to communicate and needed to speak to people and to make himself understood, and that is a whole other level of art making.

Right.

Charles never transformed his childhood fixations.

No, that's true.

Robert transformed and transcended and kept moving. And Charles, yeah. he didn't make it out. But his mental illness was so much more profound than anything Robert has. I wouldn't even call Robert ill. He went through an extremely traumatic time, there’s probably some other stuff that if he was diagnosed today, who knows, but Charles was really ill. He never stood a chance. Much like Bea, who if not ill was forever traumatized by losing her daughter. And being beaten. And all sorts of horrible stuff.

Yeah, but again, it just builds up in this story where you see that through-line of people trying to cope and inadvertently making mistakes down the line.

Yeah. I don't think anybody's evil here. It was really important to me that people emerge as human beings, not as grotesque figures even if that’s been the default and Crumb himself has perpetuated it occasionally. I really wanted everyone to be – not relatable, but humanized. His father was not a great father, but he's not evil. It's just fucked up people trying to get by.

The thing I feel with Crumb’s dad is his kids reacted against his persona and he didn't know how to handle it. Didn’t know how to respond to it. And I think I think it’s something a lot of parents deal with.

Yeah.

And I think it’s difficult for a lot of us to roll with it and accept it.

Yes, of course.

Speaking of that, one of the things I appreciated in the book was the discussion of Crumb’s relationship with [his son] Jesse, because I always thought it was extremely interesting and sad that Jesse only appears once in any of Crumb’s comics, and he's like three at the time.

Yeah.

Jesse Crumb's lone appearance, from "Aline 'n' Bob's Funtime Funnies," 1974.

Jesse Crumb's lone appearance, from "Aline 'n' Bob's Funtime Funnies," 1974.I mean, Sophie is [in his comics] from the moment she's born. His mom appears a bunch of times. His dad sometimes appears. In recent years I feel like he's made more appearances, more as a shadowy figure than a character. But Jesse's never there. So I thought it was very revealing. Again, sad and traumatic but I appreciated being given that that viewpoint of that relationship. I also thought it was interesting how Crumb takes on the blame for abandoning Jesse at so many key moments and not being able to handle him because in Aline’s book, Need More Love, she defends Robert and puts the blame on Dana. I'm sure you came across all this.

Yeah, I mean, God. It's hard. It’s much easier when you're younger to make snap judgments. If you and I were in our 20s talking about this, it would be a whole other thing.

Yeah.

I didn't know Dana. And I only spoke to a few people who really knew her well because she was pretty isolated by the end. I think that Jesse's story is probably not dissimilar to a lot of other kids who grew up with famous “countercultural” parents in some ways. Neither Dana nor Robert was ready to be a a parent, even though Dana thought she was. Robert really didn't want to be a parent, full stop.

It's funny, these questions, because I know all this stuff is in the book, and I thought about it a lot, but when I think about the book, that's not what it's about. And I don't know why that is. [laughter]

Well, this is the stuff that came to me because I had a perception of Crumb that you both reinforce and subvert in the book. There's things I wanted to know. Like Crumb has said in interviews he's never [made comics] about Jesse because he just couldn't find a way to square that circle, he couldn't make it light.

Right.

He couldn't make it into a joke like he does with his sexual mores or other things because it's just too painful. Which again, I always found fascinating and in a prurient way wanted to know more about. So there's things I came to the book wanting to know.

But when you think of the book what are you seeing it as?

Sequence from "Uncle Bob's Midlife Crisis," reprinted in Existential Comics.

Sequence from "Uncle Bob's Midlife Crisis," reprinted in Existential Comics.It's so funny when I think about it, I think about cross hatching. Or I think about how I am still fascinated by how fluid his body language is in cartooning. I think about, Uncle Bob's Midlife Crisis or I think about Genesis or I think about Mystic Funnies.

I think about these comics that are unique in the history of art and communicate so much not only about being alive but also what’s possible to communicate with drawing.

I remain even after all these years of working on this thing fascinated and kind of blown out by what he did with comicsThe unassuming fluidity of that cartooning and how much is baked into each panel, without it ever seeming effortful, without it ever seeming like, “Oh, look at me.” There's no flash to it. It's this unbelievable synthesis of of Carl Barks and Kelly and Stanley. And this language of comics that I'm still just obsessed with.

Yeah, you talk about it in the book, but he seems to have absorbed not just the art style but the method of storytelling through making these comics with his brother for years on years, so that you when you do get to Mystic Funnies, it's just so incredibly …

Yeah, it just breathes.

Yeah, exactly.

It's funny, the family stuff was the story. That's the drama of the book, that's the meat of it. But my dessert was getting to talk about how much drama Robert's able to put into a sleeve. That kind of stuff. You see that level of information in Dan Clowes, maybe Herriman, maybe Schulz. But it's so rare.

If I was daydreaming about the book, a big chunk of my brain was thinking about that, and then the other part of my brain was thinking about how to describe the networks of contacts that made Robert possible. You wouldn't believe the amount of time I spent thinking about William Cole, the guy who first brought Robert to Viking and published Head Comics. I thought about him so much. And Mike Thaler, who who gave Robert his loft when he took that acid trip. And Woody Gelman –

And Tom Wilson of Ziggy fame.

Tom Wilson. And then parallel to them, there's people like the Schenkers and Don Donahue, these networks of culture that recognized what he was doing and had a functioning system in which to place him and put him out there. I mean it's kind of unthinkable now. If you if you really think about Head Comics, it's kind of a miracle. Why on earth would a mainstream publisher put out Head Comics? I get it, they were trying to appeal to the youth, but it's a pretty radical book in 1968. It's still a radical book. And the fact that the guy who put it out was deeply invested in picture stories and publishing Shel Silverstein and Jules Feiffer and Milton Glaser. That's fascinating to me.

Right. Because if one person isn't there, one thing doesn't happen, if the pieces don't fall into place, then what?

Yeah. It was also more of a monoculture then, so if you made it in, then things could hit across all quadrants much faster.

Crumb makes John Stanley's influence obvious in a sequence from "Don't Tempt Fate," reprinted in Existential Comics.

Crumb makes John Stanley's influence obvious in a sequence from "Don't Tempt Fate," reprinted in Existential Comics.That's something I think about a lot because, and I think it's true when when we were growing up too, but you do have this idea of the United States culture. And if you pursued anything beyond what television or mainstream movies or anything offered, you were the counterculture just by default. And it was like you were taking a stance. It was definitely true of the ‘60s counterculture but even when we were growing up, listening to The Smiths is a statement in a way, because other people are like, “Never heard of them, don't know what you’re talking about.”

I remember my girlfriend told me this story about how she discovered the band The Housemartins, and she was like, “Oh, this is mine, this is me. I'm not like the rest of you.” And she was at an amusement park and they played “Happy Hour” and she got really upset. She was like, “Fuck you, this is my song.”

I tell that story because I think it shows how lines were drawn culturally. Not just in the ‘60s, but even into the ‘90s. And, especially with comics, that is not the case at all today. It's so much more heterogeneous.

It's much more heterogeneous and lines are drawn in different ways. Lines are drawn along identity lines or along political lines or aesthetic lines, but not so much thebroader cultural landscape.

What's interesting to me about Robert is, there’s a world in which he could have been Shel Silverstein or Jules Feiffer, but he just kept pushing the medium. He's such a restless artist that as soon as he had a weekly strip in the Village Voice he's like, “I hate this, I can't do it anymore, I gotta get out of this.” But there is this world, this parallel universe, where he's Feiffer or Silverstein or one of these guys who is mainstream counterculture in the sense that, you know, Feiffer was fully assimilated into New York lit/film/theatre culture.

Right, he had successful plays and movie adaptations and children's books.

Yeah. And Robert just refused to do that. But on the other hand, he also refused to be just underground. He would also do perfectly mainstream things. I guess what I'm saying is he's not a zealot on either side, which is interesting.

No he's had stuff in Premiere magazine and Entertainment Weekly and things like that.

Yeah, he shows at one of the biggest galleries in the world.

I mentioned revelations. Was there anything when you were doing working on the book that was a major discovery or revelation for you?

Let me consult the book. [laughter]

Or something that surprised you.

If anything, honestly, I was surprised at the depth of his friendships. I was surprised and moved by his friendship with Marty. I had no idea that Al Dodge and Robert Armstrong were so close with him, were so much a part of his life, and they became friendly acquaintances of mine.

I was constantly surprised. I was surprised that some of the most insightful interviews were with women who loved him in one way or another and understood him in a way that almost nobody else does. That was a surprise.

I must say I was really, really surprised by how fast and how hard he hit in the fall of 1967, that was shocking to me. I had no idea that Robert was so internationally known by the end of 1967. Then Zap comes out in February ’68, Head Comics comes out in October ’68. By the end of ’68, he's really, really famous. And known for being essentially an avant-garde artist. And he was unclassifiable, like he's in a Whitney exhibition, he’s in a gallery show, he’s in the East Village Other, he's in Rolling Stone. He's across all media. That was really surprising.

I was amazed by that and I was amazed by how he hit all these audiences individually. He hit the old school cartooning heads like Mike Thaler or William Cole or Harvey Kurtzman or Woody Gelman. But then at the same time, Ed Sanders loves him. You know what I mean? It's this unbelievable breadth of culture. That was really surprising.

Page from "R. Crumb, 'the Old Outsider,' Goes to the Academy Awards," which originally ran in Premiere magazine.

Page from "R. Crumb, 'the Old Outsider,' Goes to the Academy Awards," which originally ran in Premiere magazine.Yeah.

And that was the brilliance of Jay Kenny's suggestion to me that I really look at the underground papers because that's where you can also track his ascension. and see the difference between what he's doing and what everybody else is doing. That was that was a real surprise. Another thing I hadn’t accounted for is how they lived. I said something to Aline like, “God, it's funny you guys live so far out” or something. I don't know, I said something dopey. And she was like, “Well, you know, Robert only lived in a city for a handful of years and I've only lived in the city for like two or three years. We’re country people. We’re not city people.” It makes a certain amount of sense. In other words, they're not operators. They're not part of that thing.

They're not urban. They’re not part of the New York sophisticate.

Or San Francisco sophisticate or Chicago or whatever. That's not their world.Robert got out of San Francisco in ’69. He moved to Cleveland in ’62. So, really [only] seven years of city life in his adult life. That's it. City life is a different mentality.

Is there anything you wish you had more time to go into in the book? [Nadel laughs] Well, pick one thing. You mentioned earlier about all the people who passed away that you never got a chance to talk to, What is something you wished you had [explored] but for understandable reasons — space or trying to service the narrative — that you'd you would have liked to have gone back and and explore more.

Unfortunately, I did explore a lot, I just had to cut. [Nadel laughs]

There's a lot there.

There are things I would like to have known, very particular things that I think are important and may just be unknowable about distribution networks. Walter Bauer would have been fabulous to talk to about the East Village Other. There just weren't a lot of people still around who encountered Robert the aspiring artist, as opposed to Robert, who they knew from Cleveland, or Robert the lothario. Just on a professional level, it would have been great to talk to somebody at EVO who saw him come in the door, but all those people are gone. It's amazing how many are gone. And if the book could be twice as long, I would have probably done more on the whole underground scene, deeper into all those personalities. And probably more on American Greetings for that matter.

And more a part of that world than he is a part of Spain's world on some level. It’s interesting. It's a different thing. I guess if the book could be longer, it would be maybe be more of that. There's a version of this book that’s 100 pages on Dell Comics and 100 pages on Kurtzman.

Crumb takes on Donald Trump in "Point the Finger," from Hup #3, 1989.

Crumb takes on Donald Trump in "Point the Finger," from Hup #3, 1989.I'm assuming that's going to be the sequel.

[Nadel laughs] No. I wish. I wish there was an audience for that.

Maybe a website?

Yeah, I've heard about these websites. Tell me more.

They're fraught with problems.

You write very movingly at the end of the book –

I'm a big softy, Chris. You know me. [laughter] It’s a secret.

Movingly I thought, chronicling all the deaths that occurred [in recent years] and then Aline’s death from cancer and being there with Crumb at the end when she died. You're very present at the end there. And I wanted to know, was that a concern of yours, about having too much of a personal relationship with Crumb? Was that something you were on any conscious level worried about interfering with the book?

Yeah, absolutely. You know, this stuff is so tricky. I feel enormous warmth towards Robert. I like him. I don't always know how he feels about me. It's not like we're best friends.

The Crumbs do a jam piece celebrating their many years together, from 2007.

The Crumbs do a jam piece celebrating their many years together, from 2007.Right.

I mean, he likes me enough to have signed off on a book and come over and do an event.

There are different ways to address this sort of thing, right? Because on the one hand, of course, as a teenager, I idolized him and all this sort of shit. It kind of goes back to your first question. The best way to show that art has meaning is to take it seriously and to separate yourself enough to have a perspective on it and to write about it with honesty and care.

That said, having those experiences with him and feeling what I was feeling, which was very real, it would have been dishonest of me to pretend that I wasn't suddenly involved. I needed to write that. This sounds hokey, but that's just how it came out. I needed to do that. I needed to be able to make sense of it for myself. The book has been a really moving, profound process for me. It's not something I take lightly. And I felt enormous affection for Aline, and I do for Robert and I think that's OK.

One of the things I read in the beginning of the process was this book by James Atlas about writing biographies. He writes a lot about his relationship with Saul Bellow and how fraught it was. There's a famous story about Saul Bellow’s funeral where all the sons are there but the sons are James Atlas and Martin Amis and a bunch of other people circling around, trying to be his son. I don't want that. I know what the lines are. But it was important to me that I acknowledge that there's a person writing this book.

And I think that comes through in the choices I made about what I said, the choices I made about the structure of the book and what I'm saying and what I'm talking about. If Aline hadn’t died, I might not have done that. But it just felt like the only way I could make sense of it. And yeah, if people feel like it's too intimate or cozy, you know, what can you do?

I didn't feel like it was too intimate. Like I said, I did find it very moving. It did spur the question in my mind, which I think is always an issue whenever you're writing a biography of someone who's still alive — you have to have a relationship with that person in order to do the book. And what shape does that relationship take? And it's very clear, like you say, that you had affection for him and that you were present in his life at a very difficult time.

Yeah.

I know for me personally that would be in the back of my head all the time. Am I being objective enough? Am I being critical enough? Am I being too kind? Especially when the subject of your book has already told you, “Don't be too kind.”

Yes. I just went on instinct. That was in the back of my mind, but it wasn't present as I was writing every page. This sort of thing is such a funny process, because if I had to reconstruct how I did it or what I was thinking about, I don't know if I could. I knew what the mandate was. I had my priorities. And the thing about Robert – this is certainly bearing out in people contacting me on Instagram – everybody feels close to Robert. That's part of his magic. It's part of his thing. I write in the book that Aline is critical of him for it because everybody in business with Robert feels like he's their Robert. And that's dangerous.

That's a good segue. One thing we haven't talked about that is whenever you’re writing about Crumb, you have to deal with the racism and misogyny that's in his work. And I felt like in the book you were very frank and up front about discussing it, just being straight ahead, “Yes, this is racist, yes, this is misogynist,” even if you're talking about the value it has. But I feel like it's a very tricky business to talk about why Crumb matters. [His work] has this warm, cartoonish appeal, especially his early work, but can be so –fraught with racial and sexist and misogynist [material] that people will just say, “No thank you. I just can’t.”

It's not even necessarily a willingness, just “I don't want to subject myself to that” or “I shouldn't have to,” especially if you are a person of color. “That's just straight up offensive and shouldn't be done, even if it's even if it's satire.” I've been thinking a lot — even before I knew you were writing about him — about Crumb and what he means to me.

There's a scene in the documentary where he's talking about this drawing he did of these cute, little anthropomorphic bottles and cans, and he's saying how he drew it and this woman came up and said, “Oh, that's so cute.” And he said, “I thought this was a horror show. I had no idea what she was talking about. Cute? This is horrible.” He was drawing something he thought was terrifying and she thought it was adorable. And I feel like that gets at the core – I'm using this interview as a way to expound on my own theories here …

No, please. It's really interesting.

– but I feel like that gets at the core of why I think Crumb is worthwhile. Because I think at its core, even when he's dealing with [racist material], it's this cri du couer of: “What the fuck is wrong with me?” But in his best work you extend that to: “What the fuck is wrong with this country? What the fuck is wrong with humanity? Why is everything like this?”

Yeah.

The problem with him is many times he wants to have his cake and eat it too. I feel like that is the issue many times, especially during the ‘70s [with] Angelfood McSpade or some of the other stuff.

Does that make sense? Would you agree with that?

Absolutely. Yeah. I think there's a couple things. Robert has spent a huge amount of time thinking about himself and his vision of America and the world and all that. … I’m trying to think of something to say. How am I trying to respond?

Well, I can hone this a little.

Yeah. What do you mean?

I'm trying to articulate the struggles that I think that come with talking about Crumb, Crumb’s aesthetics from a critical angle where you have to confront the fact that he is openly dealing with racist and misogynist material. Sometimes it's satire, sometimes he's trying to confront his own racist and sexual urges, and sometimes it's just him indulging. And there’s all these things in the mix which can make his comics very interesting, but make it also make it difficult for a lot of people.

Yes, absolutely.

And as someone who's writing about his work — we’ve both written about Crumb before, you know, squaring that circle, to use an old cliche —

You can't.

You can’t, exactly.

No, and I'm OK with that. What I would say is he's a very, very complicated artist. You don't get “Uncle Bob's Midlife Crisis” without Angelfood McSpade. You can't disentangle these things.

R. Crumb drawing from Zap #2.

R. Crumb drawing from Zap #2.Right.

This is a guy who spent his entire life thinking about his own consciousness and using that as a kind of jumping-off point for an exploration of all of culture, basically, and all of morality and all that jazz. I don't have a problem with somebody making that work in the context of a larger project, I think it's just part of it. I would encourage people to accept the complications inherent in making challenging art. You don't have to like it, you don't have to read it, but I think it's important that people reckon with Crumb as an artist, full stop. I don't think it's wise or particularly interesting to dismiss an entire artist's body of work because you think that Angelfood McSpade is horrible. You have every right to, just like he's allowed to draw it. It goes both ways. But I don't think there's any disentangling. I don't think we get to say, “Oh, Robert made a mistake.” That's not what it is.

It's fully intentional. He doesn't disown any of it. He may regret some of it. He may think that it was juvenile, or he might think that it wasn't really well baked, but he's not suppressing it. It is all out there. As I write in the book, reckoning with this stuff is a big part of reckoning with the racism all throughout baby boomer counterculture and even right through to our beloved edgelord 1990s.

I'm on a text thread with some friends, and sometimes we’re like, “God, Can you believe the magazine Answer Me? Culture is filled with things that are troubling or difficult. It should not be taken as a given that people are cool with Angelfood McSpade. People shouldn't be cool with Angelfood McSpade. Of course not. And I'm not gonna prescribe to anybody how they should react, but in my case, I have the perspective and really the privilege of taking it as part of a greater body of work. I also have the privilege of, with a couple exceptions, not feeling like a target of his work. I think what's fascinating about the response to Crumb in recent years is that he lives in this funny zone. I mean, Scribner is publishing this book and it’s gotten a lot of nice attention, and he’s a canonical cultural figure. But I know that in certain pockets of deep comics world, he's anathema, which is hilarious to me. That world doesn't exist without him. And that should be reckoned with in a more constructive way. Because there's no SPX without Crumb, there's no small press comics without Crumb. But then, there are lots of “difficult” people embedded in any medium. Hs historical centrality also, again, doesn’t mean anyone has to engage with him. And yet, again, I don’t demand anyone do anything other than have a real considered think.

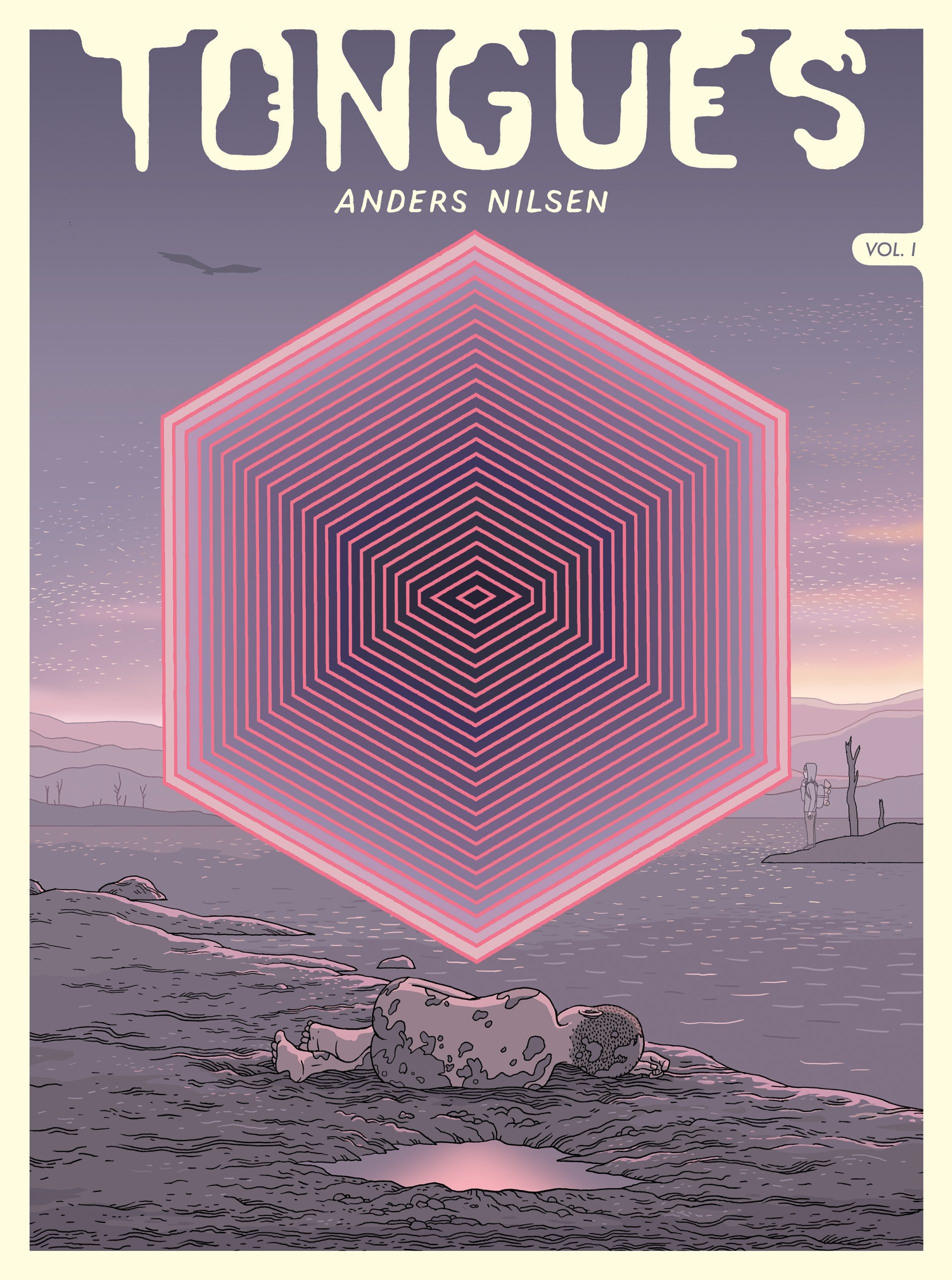

I don't think it's terribly interesting or helpful to throw out somebody's entire body of work because you saw something on Twitter.. I’m hoping that my upcoming compilation, Existential Comics, which reprints the best of his work from 1979 to 2004, will offer a helpful way into his work.

Opening panel from "Walkin' the Streets."

English (US) ·

English (US) ·