The Editors | July 17, 2025

Today we are very pleased to bring you an excerpt from author and manga scholar Eike Exner's latest book, Manga: A New History by Eike Exner. The book, published by Yale University Press will be available on Aug. 5, 2025. The publisher describes the book thusly:

The immensely popular art form of manga, or Japanese comics, has made its mark across global pop culture, influencing film, visual art, video games, and more. This book is the first to tell the history of comics in Japan as a single, continuous story, focusing on manga as multipanel cartoons that show stories rather than narrate them. Eike Exner traces these cartoons’ gradual evolution from the 1890s until today, culminating in manga’s explosion in global popularity in the 2000s and the current shift from print periodicals to digital media and smartphone apps.

Over the course of this 130-year history, Exner answers questions about the origins of Japanese comics, the establishment of their distinctive visuals, and how they became such a fundamental part of the Japanese publishing industry, incorporating well-known examples such as Dragon Ball and Sailor Moon, as well as historical manga little known outside of Japan. The book pays special attention to manga’s structural development, examining the roles played not only by star creators but also by editors and major publishers such as Kōdansha that embraced comics as a way of selling magazines to different, often gendered, readerships. This engaging narrative presents extensive new research, making it an essential read for enthusiasts and experts alike.

The section below, reproduced by permission, comes from Chapter 3, "1941-59: Transwar Continuity and theCentral Role of Monthly Kids' Magazines." We'd like to thank Yale University Press for allowing us to run this excerpt. — The Editors

***

Around the time when the Tokiwa-sō became home to multiple mangaka, in the mid-1950s, the trajectories of the Japanese and American comics industries began to diverge significantly. A chronic moral panic over comics reached a fever pitch in both countries at this time. In the United States, adventure comic strips that replaced cartoonish drawing and humor with more realistic styles and serious plots had emerged starting in the late 1920s, followed by a diversity of genres such as superheroes, crime, romance, horror, and Western. Such more plot-driven comic strips were soon published in so-called comic books of several dozen pages. Most comic book publishers, such as Detective Comics (DC) and Timely Publications (today known as Marvel Comics), were newly founded in the 1930s and limited to comics. This represented a stark contrast to comics publishing in Japan, where since the 1930s comics were primarily published in magazines issued by major publishing companies with more diverse product lineups. Nonetheless, American comics had celebrated a resurgence in occupied Japan, both in the form of comic books brought by American soldiers as well as translations. Princess Knight was preceded in Shōjo Kurabu by the American strip Little Lulu, for example, and in 1949 several issues of Detective Comics’ Superman comic books, featuring superhero strips like Superman and Batman as well as humor strips, had been published in Japanese translation.

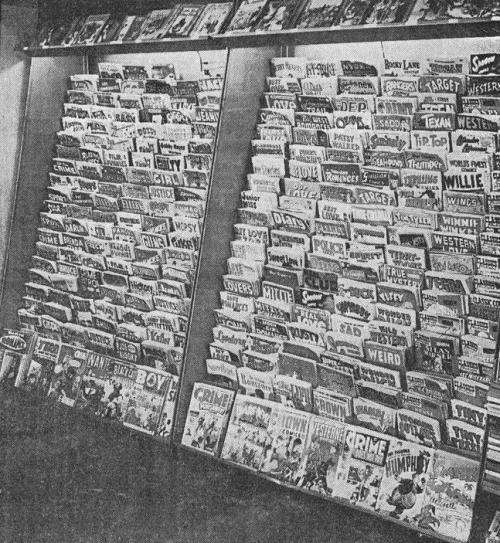

By 1954 crime and horror comic books, which often featured graphic depictions of violence, constituted “about a quarter of the total of 422 comic-book titles issued last March” in the United States, according to the New York Times. Critics considered the amount of violent material in comics an urgent social issue due to the popularity of comics at the time: In 1948 the size of the American comic book industry was estimated, in articles in the New York Times and Newsweek, at three to four hundred different titles selling a total of sixty to one hundred million (!) issues each month. Newsweek further estimated that “pulp comic books” (American akahon, if you will) were read by “probably three-fourths of all Americans between 8 and 30.” American visitors to Japan decades later would express surprise at the ubiquity of comics there, unaware that comics used to enjoy a similar degree of social permeation in the

visitors’ own country as well.

The anti-comics fervor in the United States entailed congressional hearings and public burnings of comic books. Out of fear that distributors might stop carrying their comics altogether, comic book publishers reacted to this pressure by self-regulating via a Comics Code in 1954. Among stipulations regulating the size of the word crime on covers or mandating that “divorce shall not be treated humorously nor represented as desirable,” the code included blanket prohibitions on “sex perversion,” “sympathy for the criminal,” and “the word horror or terror,” as well as requirements that comics never “create disrespect for established authority” and that “in every instance good shall triumph over evil.” The prevalence of superhero comics in the United States following the 1950s was the direct result of the Comics Code, as other genres were devastated by the new restrictions. Comics publishing in general was decimated: Between 1954 and 1956, the number of comic book titles issued in the United States fell by over 50 percent.

In Japan the furor over inappropriate reading material for children encompassed more than just comics and became known as the banish bad books movement (akusho tsuihō undō). It was also milder than in the United States, with reports of book burnings involving comics being primarily anecdotal in Japan. The movement’s furor reached its zenith in 1955–56, and this temporal proximity to its American counterpart was no coincidence. In his autobiography, Osamu Tezuka blames the Japanese anti-comics movement of the 1950s in part on the Japanese translation of the American book The Game of Death: Effects of the Cold War on Our Children. Though not exclusively concerned with comics, The Game of Death featured an entire chapter on them (“Niagara of Horror”) and quoted the infamous anti-comics psychiatrist Fredric Wertham. The Game of Death pilloried comics as a medium that, according to the author, familiarized children with death and killing to turn them into future soldiers. Providing evidence for Tezuka’s thesis, the depiction of guns and swords was repeatedly cited as evidence of comics’ harmful nature by Japanese anti-comics activists at the time.

Just as there had been congressional hearings on the danger posed by comics in the United States, the Japanese prime minister’s office’s “central juvenile issues council” in 1954 began investigating the need for legislation to restrict the content of children’s magazines. But unlike in American comics, blood, murder, and overt sexuality were extremely rare in Japanese ones at the time (ironic, given criticism of manga as particularly violent and sexual today). Furthermore, whereas American comic book publishers had been divided because most of them specialized in specific genres, and hence would be affected by regulation to different degrees, Japanese publishers of children’s magazines were aligned in their interests and coordinated their response.81 In 1955 eight major publishers, including Kōdansha (Shōnen Kurabu/Shōjo Kurabu), Kōbunsha (Shōnen/Shōjo), Shōgakukan, Shūeisha (Omoshiro Bukku), Shōnen Gahō-sha (Shōnen Gahō), and Akita Shoten (Bōken’ō), founded the Japanese Children’s Magazine Editors’ Association and began issuing a monthly newsletter to counter criticism of their industry. And while these publishers conceded that some content was inappropriate for children, their refusal to establish formal restrictions akin to the Comics Code in the United States enabled Japanese comics to continue growing in manifold ways that were now closed off to their American counterparts.

In addition to the full-throated embrace and defense of comics by major publishing houses, another development with long-lasting effects for the future development of manga occurred in the late 1950s. Between 1954 and 1959 the now-common assistant system began to emerge. A large factor in this development was the high demand for comics created by proven star authors, and the practice by some of these stars to take on more work than they could reasonably handle: Overwork had been a presumptive factor in the death of Eiichi Fukui; the Fujio Fujiko duo missed several deadlines in 1955, which almost ended their career; and most famously, Osamu Tezuka was constantly hounded by editors of the multiple publications for which he was simultaneously drawing comics — usually around ten different publications in the mid-1950s. Early on, Tezuka had solicited help from his mother and editors for more

mechanical tasks such as filling in black surfaces in panels. As mentioned above, in 1954 Tezuka was also assisted by Shōtarō Ishinomori and one of the Fujio Fujikos.

Tezuka reportedly finally began hiring full-time help in 1957, and according to one former assistant he usually employed at least five by 1959. By then, he was publishing in twice the number of magazines, which makes obvious the need for assistants. Tezuka would generate the pencil outline for each story and draw the main characters as well as some objects, while his assistants filled in the rest and presumably inked some finished pencil drawings as well. The contrast in Japanese comics between relatively simple character faces (drawn by the named creator) and detailed backgrounds (drawn by one or more unnamed assistants) later noticed by foreign observers partly derives from this system of production. Another effect of the assistant system was that it produced a continuous supply of experienced creators. Aspiring mangaka honed their skills and acquired firsthand experience of the business under the

tutelage of an established star, who could then vouch for them and recommend them to editors who trusted his (and eventually also her) judgment.

Alongside the normalization of assistant labor during the mid to late 1950s, comics in boys’ and girls’ magazines began to diverge. The popularity of Princess Knight already during its original serialization from 1953 to 1956, together with the appearance of comics-centric magazines for girls such as Nakayoshi and Ribbon during this period, started a tradition of comics tailored to female audiences beyond the gender of their protagonists. A central factor in this development of a strand of manga specific to girls’ magazines was the work of the illustrator Macoto Takahashi.

Takahashi had started drawing Tezuka-influenced akahon comics in 1953, before transitioning to comics for the rental market. In contrast to Tezuka, Takahashi was less interested in comics as a medium than he was in illustration. In his rental comics, he began to draw female characters less cartoonishly than was common at the time and made them more akin to so-called lyrical pictures (jojōga) of girls gazing melancholically off-screen, a common element of girls’ magazines since before the war. Tezuka had already included some white highlights in Sapphire’s eyes in Princess Knight, but Takahashi increased their number and detail, along with the overall expressiveness of the eyes. Similarly, while Sapphire was portrayed as attractive within the context of the story (largely via other characters’ referring to her as beautiful), she was still obviously a cartoon character. Takahashi started to draw his characters as elegant, beautiful figures that resembled fashion illustrations.

His love of illustration also led Macoto Takahashi to devise three further innovations in his comics that would be imitated by others:

(1) extradiegetic decorations, especially flower petals, within and outside of panels; (2) free-floating extradiegetic narration and transdiegetic thoughts next to close-ups of characters’ faces, without enshrining them in text boxes or thought balloons, as was established practice; and (3) so-called style pictures (sutairu-ga or sutairu-e): vertical panels featuring characters from the story not as part of the narrative but to showcase their beauty and fashion. As a Francophile, Takahashi also frequently used European settings and ballet in his comics, which would help establish both features as popular material for girls’ manga. One concrete benefit of foreign locales was that they made it more acceptable to editors to depict kissing or hand-holding than stories set in Japan.

In 1957 mainstream magazines such as Shōjo began to solicit comics from Takahashi, greatly increasing his influence. Style pictures quickly proved popular with several mangaka and with editors who encouraged even more artists to adopt them as well. One of the reasons for their popularity with editors was that style images could be used to encourage readers to send their own drawings to magazines, which allowed editors to measure how popular individual serials were. Although decorations like flower petals would largely remain confined to comics in girls’ magazines, free-floating thoughts and figures of characters outside of or layered over panels would later also appear in comics in boys’ magazines. Note, however, that even girls’ comics making heavy use of the above elements pioneered by Macoto Takahashi constituted a minority of the manga published in girls’ magazines until the early 1970s. This is important to keep in mind because the term shōjo manga (girls’ comics) is sometimes used synonymously with such comics, but styles used in girls’ comics at this point were still diverse, and even manga that did make use of flower decorations and style pictures usually consisted primarily of conventionally paneled pages, including those by Takahashi himself.

When considering gendered differences between “shōnen” and “shōjo” manga, one must likewise keep in mind that differences were not purely a natural result of their readers’ desires, but shaped by primarily male editors, some of whom held rigid notions of what was appropriate for boys on the one hand and girls on the other. Editors, for example, insisted on overly feminine speech patterns that were more conventionally “girlish” than the language used by their actual readers. And when Takerō Makino, the editor responsible for the creation of Princess Knight, joined Shōjo Kurabu’s editorial team in 1951 and proposed including a Japanese dictionary as a supplement, a colleague reportedly scoffed at the idea, asserting that “girls are interested only in pretty things and cute things” (even though, when Makino’s idea was eventually adopted the following year, the accompanying Shōjo Kurabu issue sold out). Similarly, when male mangaka Tetsuya Chiba in the late 1950s felt tired of the constant demure and passive depiction of girls, he drew a comic strip for Shōjo Kurabu in which a girl slaps a boy bullying her, only to have an editor insist that Chiba would have to change the scene. But Chiba did not finish the edit in time and his original draft went to print, leading to a heap of fan mail from readers who appreciated seeing a girl act so assertively. As is evident from the contrast between such editors’ attitudes and actual readers’ reactions, the kind of reading material that gendered magazines considered appropriate for boys or girls not only was not necessarily reflective of readers’ preferences but sometimes directly contradicted them.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·