Hank Kennedy | November 13, 2025

“Free speech is the right to shout ‘Theater!’ in a crowded fire.” — Abbie Hoffman, Soon to be a Major Motion Picture

“Congress shall make no law... abridging the freedom of speech or of the press.” Whether one learned those lines from a civics class or an Above the Law song, those words from the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution are the guarantor of freedom of expression for anyone in the United States. Well, unless certain powerful people get their way.

In 2021, NYU Press published The Fight For Free Speech: Ten Cases That Define Our First Amendment by media attorney Ian Rosenberg. That same year, First Second published a comic book version of Rosenberg’s book entitled Free Speech Handbook: A Practical Framework for Understanding Our Free Speech Protections, adapted by Eisner-nominated artist Mike Cavallaro. Those two books were released in the aftermath of the first Trump administration, and as we enter the second iteration, the Free Speech Handbook has likewise returned in a new edition.

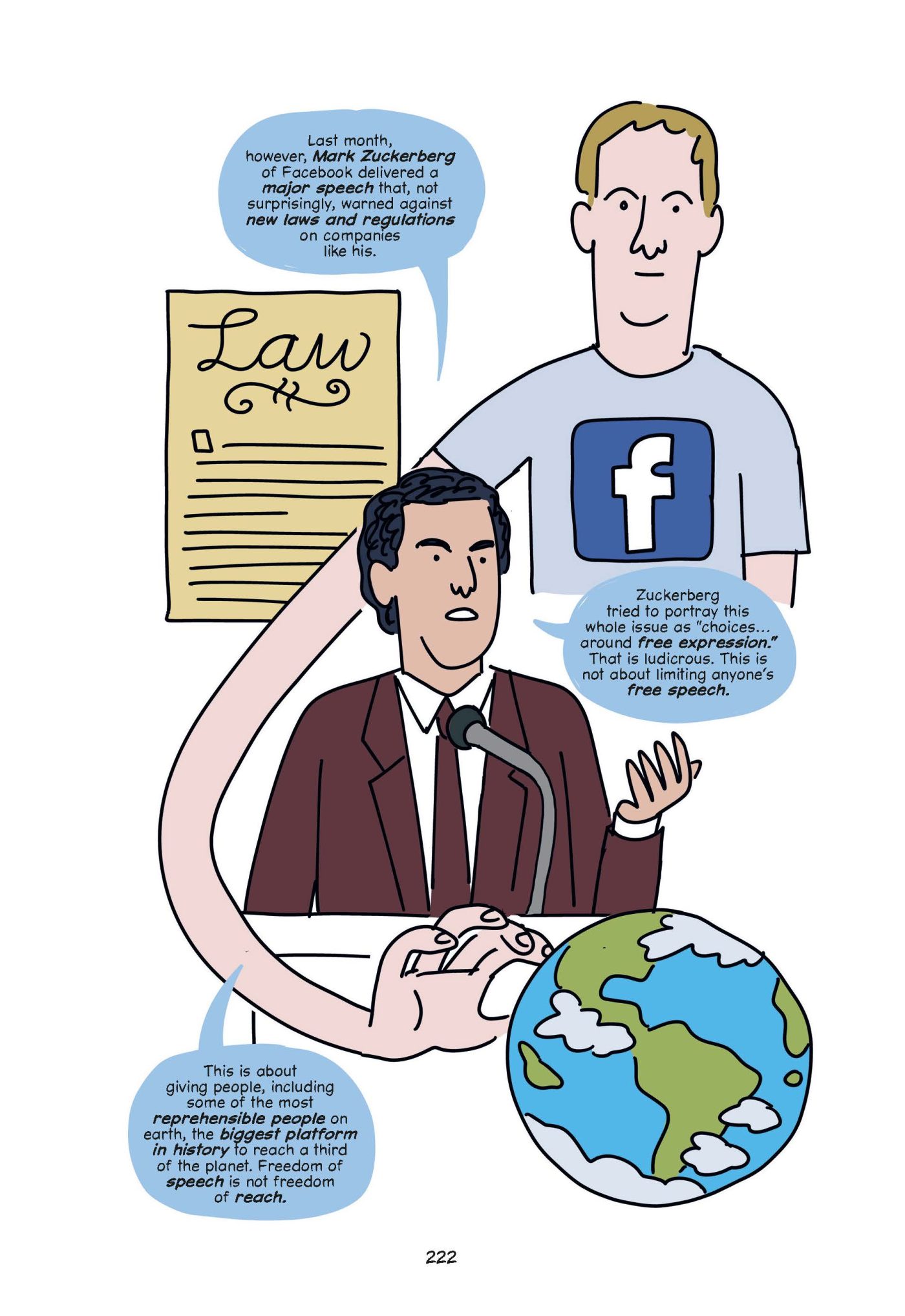

The comic looks at various aspects of freedom of speech exemplified by Supreme Court cases, arranged in chronological order. Topics include libel, obscenity, parody, hate speech, and the right of students to protest. Rosenberg guides readers with commentary along the way. There is an effort to tie these historical cases with more current issues, such as President Trump’s criticisms of libel laws, his attacks on Saturday Night Live, the Charlottesville Unite the Right Rally, and the March for Our Lives against gun control. Some are more apt comparisons than others, and attempts to draw comparisons between corporations and businesses punishing expression versus government doing the same mostly show how workers often check their constitutional rights at the door when punching in.

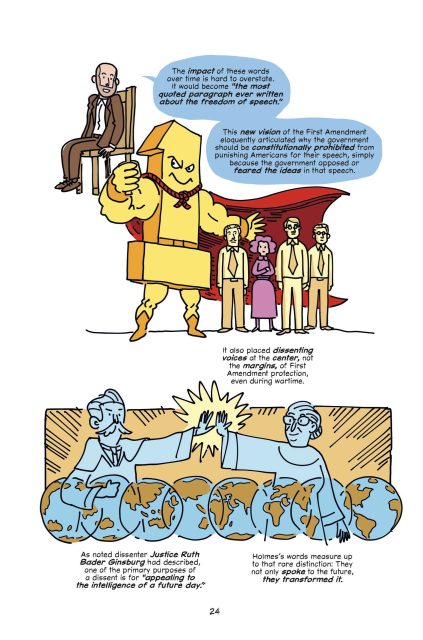

Free Speech Handbook gets off on the wrong foot immediately. In discussing the prosecutions of World War I dissidents under the Sedition Act, Rosenberg bemoans the cliched overuse of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ adage “You can’t shout fire in a crowded theater,” the source of Hoffman’s above joke. Most have long since forgotten that Holmes actually meant that it was unprotected speech to falsely shout fire in a crowded theater. To do so would cause unnecessary panic violate the “clear and present danger” exception to free speech.

Free Speech Handbook gets off on the wrong foot immediately. In discussing the prosecutions of World War I dissidents under the Sedition Act, Rosenberg bemoans the cliched overuse of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ adage “You can’t shout fire in a crowded theater,” the source of Hoffman’s above joke. Most have long since forgotten that Holmes actually meant that it was unprotected speech to falsely shout fire in a crowded theater. To do so would cause unnecessary panic violate the “clear and present danger” exception to free speech.

Yet, this glosses over the real issue with Holmes’ thinking and decisions. Legal scholar Zachariah Chafee said the situation of anti-war activists was more comparable to a “man who gets up in a theater between the acts and informs the audience honestly ... that the fire exits are too few or locked ...” Howard Zinn asked in A People’s History of the United States whether the war was “a ‘clear and present danger,’ indeed, more clear and more present and more dangerous to life than any argument against it? Did citizens not have a right to object to war, a right to be a danger to dangerous policies?” Rosenberg does not acknowledge these criticisms.

In showing another instance of dissent’s vulnerability in wartime, Rosenberg makes concessions to what was then-prevailing taste. In a section on Unitarian high school students who protested the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands to school, Rosenberg writes “anger directed toward the young protesters must be considered (though not justified) in the context of the national attitude toward the Vietnam war at the time.” This comes after a section detailing threats to the high school students and their families by people favoring the war. Its an odd choice for a supposedly pro-free speech book.

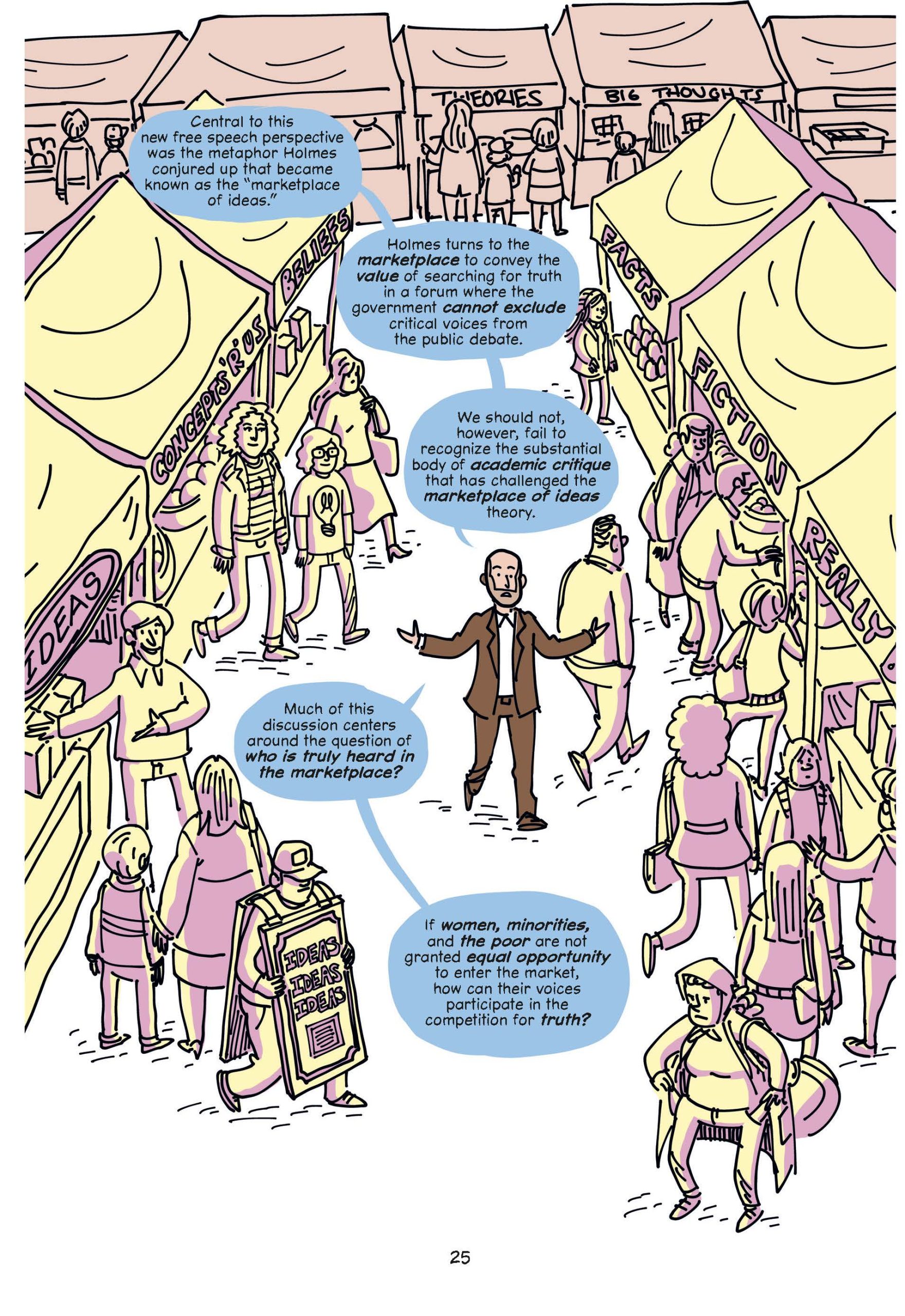

If other sections are less politically disagreeable — and one on Jerry Falwell’s suit against Larry Flynt is quite amusing — the way the book is presented makes most of them difficult reading. Although Publishers Weekly’s reviewer claims the book “keeps speechifying to a minimum,” this is incorrect. Free Speech Handbook is weighed down by an overabundance of text on each page. For the most part, these are not speech balloons or narrative captions, just block after block of text. Rosenberg quotes extensively from various lawyers and judges, who are already a verbose bunch.

Cavallaro’s cartooning never gets much room to breathe given how wordy the pages are. His work is exaggerated, yet simple and his choices are sadly typical for a nonfiction comic. There are many talking heads and portraits floating in a white void. Occasionally, there are more creative choices, like President Trump as the Twitter bird or Jehovah’s Witnesses in a red, white, and blue prison cell. More often than not, though, the crowded pages are of lawyers and Supreme Court justice’s faces swimming in motions, verdicts, and dissenting opinions.

It’s not that legal proceedings necessarily make for boring comics. A counterexample is Len, A Lawyer in History, illustrated beautifully by Seth Tobocman, a longtime contributor to World War 3 Illustrated. It does require a willingness to let images do more of the job of communicating, and a quicker, more fluid structure. The present volume is never able to build up much momentum and remains a slog.

First Second, the initial publisher of Free Speech Handbook (the new release is from 23rd St. Books), also published Dictatorship!: It’s Easier Than You Think which I was definitely not a fan of. This comic is more politically to my liking, but I was constantly asking why this needed to be a comic at all. The medium added little to the proceedings. Today, Americans face an assault on the First Amendment rivaling the darkest days of the postwar Red Scare. It’s more important than ever for dissidents to use our rights to freedom of press, assembly, and speech now, to ensure that we will continue to have them. Unfortunately, this comic is not the best introduction to these issues.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·