Shaenon Garrity | July 16, 2025

Writing about My Hero Academia for TCJ, I called Weekly Shonen Jump the most formulaic of the big manga magazines in Japan, but that doesn’t mean it’s static. It has its trends — the 1980s spate of sci-fi-flavored battle manga, the 2000s turn toward adventure fantasies like Naruto and One Piece — and those trends often influence the rest of the manga industry.

Right now, there’s a trend in Jump manga I’m not entirely sure how to qualify. I’m calling it Chainsawin’, because I first noticed it in Tatsuki Fujimoto’s Chainsaw Man, which may be the exemplar of the type. Chainsawin’ manga are rude and crude, at least on the surface. They start from outrageous high concepts. The protagonists frequently are, or transform into, lanky, monstrous weirdos: teenage awkwardness embodied and made cool, not unlike 1990s American comic-book antiheroes like Venom and Spawn. Some of these manga run not in the Shonen Jump print magazine, but exclusively on the Shonen Jump+ app, which perhaps allows them to edge closer to the “Older Teen” end of the age ratings. (Chainsaw Man itself ran first on Jump and moved to Jump+ with the start of its second and current arc.)

But under the gasoline-powered edge, Chainsawin’ manga have heart and brains. The protagonist of Chainsaw Man might start as a simple bro with simple needs, but only so the manga can make him climb a shonen manga version of Maslow’s hierarchy (the need for sex is replaced by the need to see boobs) toward love, self-respect, and, ultimately, self-actualization. Via turning into a chainsaw man.

But under the gasoline-powered edge, Chainsawin’ manga have heart and brains. The protagonist of Chainsaw Man might start as a simple bro with simple needs, but only so the manga can make him climb a shonen manga version of Maslow’s hierarchy (the need for sex is replaced by the need to see boobs) toward love, self-respect, and, ultimately, self-actualization. Via turning into a chainsaw man.

Maybe this increasing complexity is the nigh-inevitable outgrowth of Jump manga being so damn long. The manga ostensibly under discussion in this column, Dandadan by Yukinobu Tatsu — a former assistant artist on Chainsaw Man — currently comprises 19 collected volumes, a piffle compared to, say, One Piece with its 111 volumes and counting. But 19 volumes used to be a healthy run for a shonen manga. In a publishing industry increasingly driven by blockbusters and less able to take risks, hit series are pushed to keep going as long as possible. Sure, the big shonen magazines have always had their 100-volume behemoths, but if Dandadan was Bobobo-bo Bo-bobo, it’d nearly be over by now.

And when comics go long, they often get complicated and dramatic. Back on the late, lamented blog Websnark, Eric Burns observed this phenomenon in long-running webcomics; strips start with two stick figures on a couch and end with 35 characters from six parallel universes fighting God, or start with two gamers on a couch and end with two gamers and an on-panel suicide. It’s how you get Loss. But it’s also, maybe, how you get Chainsawin’.

But I’m not here to sneak Loss into a TCJ column. I’ve been summoned here to talk about Dandadan, the story of a boy’s search for his stolen genitals.

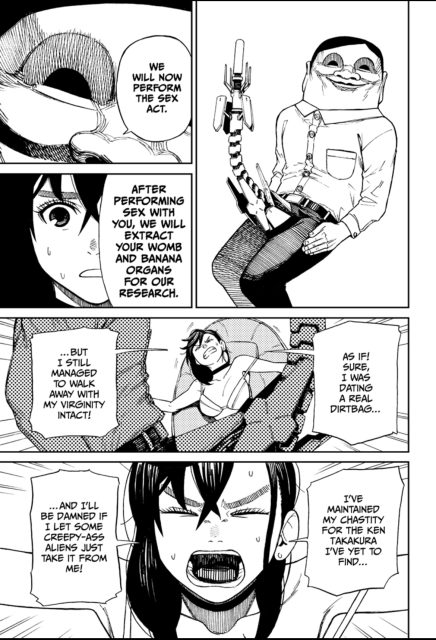

The boy, baby-faced teen nerd Ken “Okarun” Takakura, believes in aliens and other X-Files-type conspiracies. His tough classmate Momo Ayase, introduced to us while kicking a guy in the face, believes in ghosts and the supernatural. Each thinks the other’s beliefs are ridiculous, so they challenge each other to prove it. Within the first chapter, this results in: a) aliens abducting Momo; and b) a yokai called Turbo Granny stealing Okarun’s penis while yelling, “Let me gobble your schlong!”

But it’s not all bad! The alien abduction unleashes Momo’s latent spiritual powers, so she can “grab auras” and engage in psychic battles. And Okarun winds up with Turbo Granny’s powers, causing him to turn into a big skinny twisted monster thing with super strength and speed. Eventually he gets his penis back, but then loses his testicles. And so it goes.

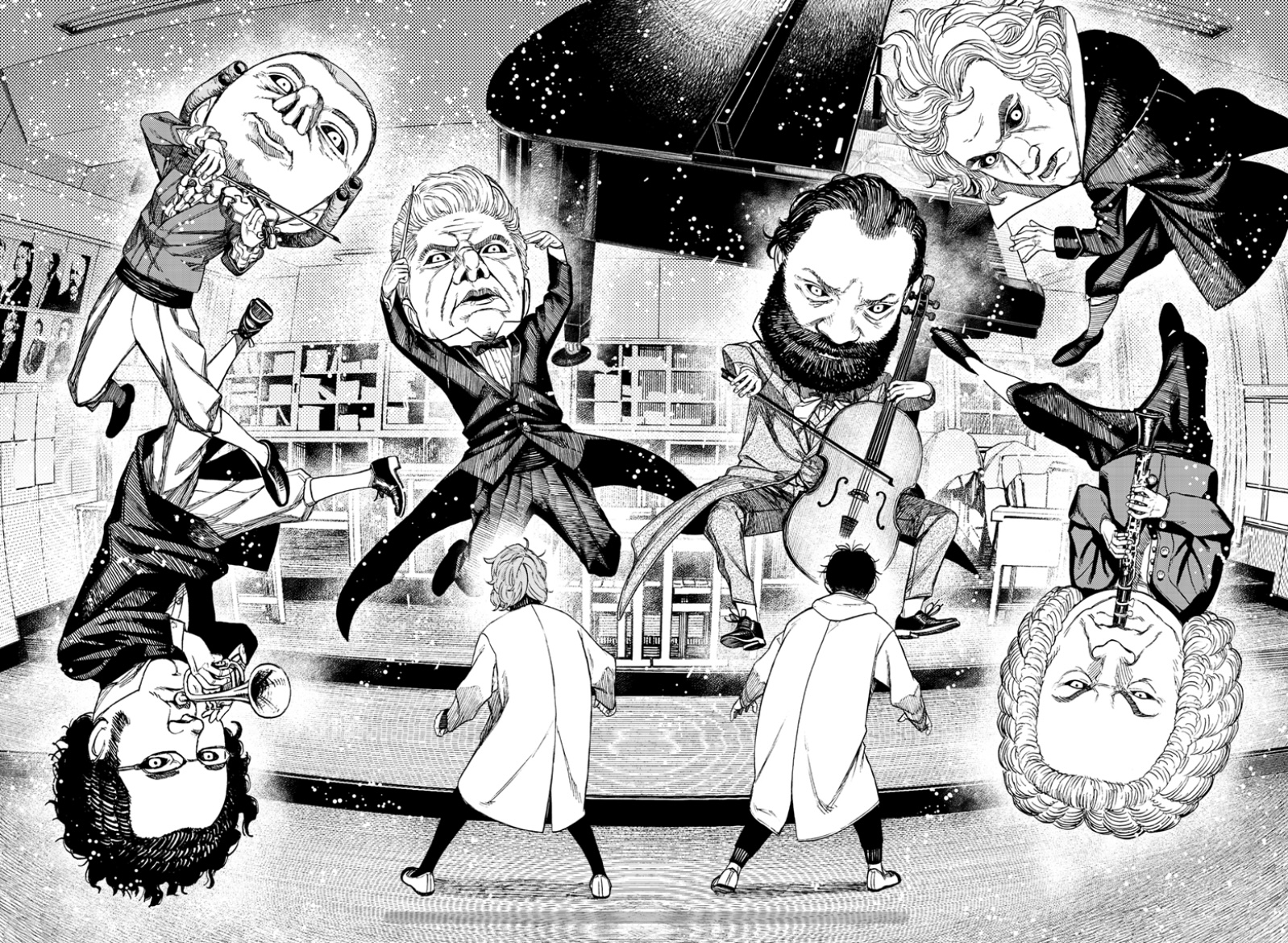

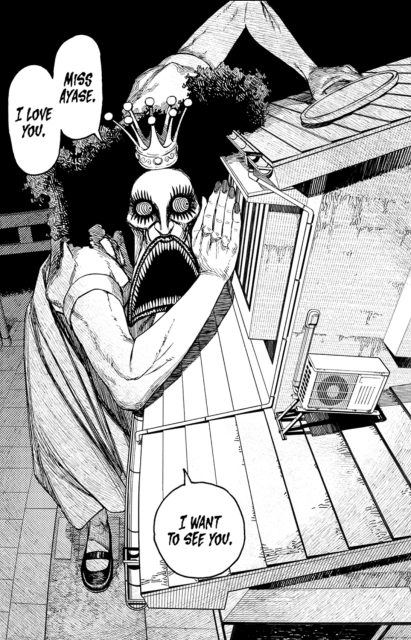

Big skinny twisted monster things are an important part of Chainsawin’. Dandadan is full of great creepy-looking creatures, even in the early chapters where the art is otherwise on the sketchy side. Okarun and Momo encounter a wide range of supernatural and paranormal entities: classic yokai, Japanese urban legends like the Slit-Mouthed Woman, Western cryptids like the Loch Ness Monster, a cattle-stealing alien, a space monster that looks suspiciously like Cthulhu, tulpas that take the form of European composers, a polka-dotted Giant Mongolian Death Worm …

The early chapters bounce around hyperactively without much of a plot or point. Tatsu sometimes seems to push the action to a breakneck pace, with lots of shouting and frantic explanations of what the hell’s happening, to cover up for his uncertainty about where the story is going. The first story arc ends neatly enough at Chapter 8, but it must have gone over well with readers, and Tatsu had to find a way to keep it going past one volume’s worth of manga.

Fortunately, Tatsu may not be much of a plotter, but he has a talent for coming up with eccentric characters and creatures for them to fight, and over time they accumulate to form not only an extensive cast, but a setting: a weird world where the truth is out there and every cockeyed belief humanity has ever held is real. One of the interesting things about Dandadan is that characters stick around, even those introduced as one-off baddies or background figures to move a plot along. The cattle-stealing alien becomes a regular, as does the Slit-Mouthed Woman. Some serpent-worshipping volcano cultists from early in the manga disappear for over 100 chapters, only to reemerge in recent installments to help fight a sharknado. (“What in tarnation is up with these darn sharks!”)

Meanwhile, Momo and Okarun acquire, in classic Shonen Jump style, a band of fellow teens with strange powers of their own, to help them win battles and discover the power of friendship. They gather at Momo’s grandma’s house, which sometimes turns into a mecha, and later start a club for unexplained phenomena at school. And I would be remiss to overlook Momo’s grandma, easily my favorite character. Like most old ladies who live on shrine grounds in manga, she has vaguely Shinto spiritual powers and knows ancient lore; unlike most of them, she’s hot and busty, an acknowledgement that grandparents of teenagers aren’t always that old and/or an example of Dandadan’s odd and random approach to doling out fan service.

Dandadan has its share of fan service (including, for the ladies, Okarun losing his clothes and dudes fighting in tighty whities), but, in the true spirit of Chainsawin’, it’s less into cheesecake than dirty jokes and cussing. A lot of rude language in Japanese is based on impolite forms of address rather than taboo words, which always presents a challenge to English translators. The Viz translation team is up to it, giving the characters absolute potty mouths:

“Human sacrifice can eat shit!”

“Space aliens … your ass is grass!”

“Who’re you calling a vampire, blockhead? I ain’t one of those turds.”

“If you had my wiener, would it save your son?”

Okay, that last one isn’t rude; I just like it.

Okarun belongs to a rich tradition of nebbishy shonen manga protagonists who get into sexually humiliating situations while surrounded by hot girls, but losing his genitals takes the trope to an extreme. Here the translation is simpler, as the English phrase “family jewels” has an almost exact Japanese equivalent, kintama, “golden balls.”

Tatsu’s art, as mentioned some paragraphs ago, starts out rough. The action scenes are exciting, but for a long time it’s debatable whether they’re well-drawn or just enthusiastic. (Read enough comic books, and you start to question whether there’s a difference.) As Tatsu grows more sure of his skills, fights engulf entire chapters and sprawl across two-page spreads with crowds of figures duking it out. Tatsu and/or his assistants are good at drawing architecture; buildings in Dandadan often warp into M.C. Escher patterns, twist like the city streets in Inception, or transform into robots. Realistic sci-fi technical illustration coexists with creepy horror art which coexists with cute chibi characters. A mecha stabs a kaiju with Tokyo Tower. Are you not entertained?

So far, the bulk of Dandadan has been taken up by a lengthy alien war plot. It kicks off around Volume 4, when the characters have a revelation: “These yokai and demons are what protect the Earth from alien invasion!” It turns out that Momo’s and Okarun’s preferred forms of weirdness aren’t separate after all; the supernatural entities of Earth are the planet’s antibodies against extraterrestrials. The pyramids of Egypt and Latin America are transmission devices, as are Japanese kofun burial mounds! Erich von Däniken was right! When “globalists from outer space” show up, Momo, Okarun, and their friends join this age-old battle, along with so many entities from previous storylines that, if you’re me, it’s hard to keep them all straight. But fear not, for the original premise of the manga has not been forgotten: Okarun’s stolen testicles can be used to power alien technology.

It’s all good dirty space-opera fun for a while, but a turn toward serious violence in Volume 12 casts a pall over the invasion and triggers a lengthy flashback showing the devastation the alien globalists have wreaked on other planets. The stakes are high and the war has weighty emotional consequences, even when Momo is unleashing a psychic attack she developed by working at a maid cafe and Okarun is astral projecting through telephone wires. Is this … is this the power of Chainsawin’?

It is.

One part of Chainsawin’ is getting dark and gritty, but to avoid mere edgelordliness, a Chainsawin’ manga has gotta have heart. The emotional core of Dandadan is the relationship between Momo and Okarun, opposites who inevitably attract. It’s hard not to root for a couple of weird kids to get together, and over the course of their adventures they progress from nervous hand-holding (including what may be the only scene in a shonen battle manga that could accurately be compared to Scorsese's The Age of Innocence) to increasingly confident declarations of love. To add depth, other characters receive flashbacks to traumatic or touching backstories, but the two leads are wisely kept light on baggage.

One part of Chainsawin’ is getting dark and gritty, but to avoid mere edgelordliness, a Chainsawin’ manga has gotta have heart. The emotional core of Dandadan is the relationship between Momo and Okarun, opposites who inevitably attract. It’s hard not to root for a couple of weird kids to get together, and over the course of their adventures they progress from nervous hand-holding (including what may be the only scene in a shonen battle manga that could accurately be compared to Scorsese's The Age of Innocence) to increasingly confident declarations of love. To add depth, other characters receive flashbacks to traumatic or touching backstories, but the two leads are wisely kept light on baggage.

The sentimental side of Dandadan has come out stronger in the stories following the end of the big invasion arc. Post-invasion, a bishonen new teacher shows up at our heroes’ school and is revealed to be the immortal Count Saint-Germain, up to no good. Soon paranormally powered students and teachers are wreaking havoc, one foe at a time. The tournament-style plotting feels like a more conventional fighting manga, with details that seem designed to evoke Shonen Jump classics: power attacks get elaborate names like in Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure or Hunter x Hunter, and a spiritual power called the “Id Cosmos” is teased, triggering happy associations with the Cosmo of Saint Seiya. We get hints about something called Dandadan, which has not previously come up anywhere in the manga except the title.

But this new focus on face-offs and collecting powers is balanced with growing character development and more complex personal stakes. (SPOILERS: This shift is marked by a resolution to the two most basic stakes in the series: Okarun gets his balls back.) Following a lengthy Momo-centric storyline, Momo is shrunk to doll size and begins to vanish from people’s memories (a surprisingly common manga plot device that could be the subject of a whole 'nother essay with a whole lot of CLAMP references). Naturally, this happens just as she and Okarun are on the verge of resolving nineteen volumes’ worth of romantic tension. Now the heart of the story is not just Okarun’s feelings for Momo, but everyone’s feelings for her. Perhaps this was always the way for a manga that treats every weirdo who shows up as important.

Plot-wise, Dandadan could go on forever. The premise of “everything that’s ever been questioned by skeptics is real” allows for endless possibilities. (In a recent chapter, Okarun brings up genuine government cover-ups like MK Ultra and the Tuskegee experiments. Could Momo and Okarun come to the U.S. and get justice for Henrietta Lacks?) If there’s a natural conclusion to the story, it will grow out of the characters. The cast of Dandadan is dynamic: these kids are growing up. Shonen Jump can stretch Dandadan out for a long time, but eventually Okarun and Momo will hook up, and the other characters will figure out their lives, and they won’t be the misfit, weirdness-hunting teens that this manga is about. The weirdness will always be around. The kids won’t.

Tom Spurgeon once opined that the saga of Spider-Man, a character whose creepy-crawly design and angsty personality may make him the proto-Chainsawer, should have ended in 1975 with Amazing Spider-Man #149. (This is important. All thoughts about Spider-Man from Tom Spurgeon are important.) In that issue, Peter Parker moves on from the death of his first girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, and commits to an adult relationship with Mary Jane Watson. The Amazing Spider-Man is the story of a teenager learning to handle adult power and responsibility, so when he leaves his teenage life behind, his character arc is over. And that’s why most Spider-Man comics since then, good, bad, and indifferent, have felt … inessential. Spider-Man is a dynamic character trapped in a static comic book universe.

But even popular manga are allowed to end, so dynamic characters can grow out of their stories. Chainsawin’ cuts through the stasis. Dandadan has a possessed lucky cat statuette and an alien girl in a Godzilla suit and guys who run into a fight yelling, “Boobies!” It also has teenagers learning about the weird, wide world and figuring out how they want to inhabit it. That’s manga with balls.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·