SPOILERS FOR BOTH MOVIES TO FOLLOW

I did something for the first time this week: I saw two movies in one day. The first was an early showing of Chistopher Nolan’s Interstellar on a very large screen (billed as IMAX but not actually); the second was a screening of Mufasa: The Lion King in both 3D and 4DX. A movie about outerspace and black holes made with practical models, and a movie about wild animals made with CGI: what a strange time to be alive and going to the movies.

As the first and most likely ONLY human who will ever experience Interstufasa, I felt I must commemorate the day.

Interstellar came out 10 years ago. Friends who saw it when it opened disliked it intently, which discouraged me from seeing it in a theater. A few years later, I watched it on my home TV and found it absolutely haunting. A recent IMAX re-release became the biggest grossing IMAX re-release ever – I wanted to see it on the truly immense screen of New York’s only IMAX but it sold out at all showings almost immediately. It’s become a bit of a cult classic over the last ten years.

Luckily it was playing at my local on a very large screen. Armed with a peppermint mocha from Starbucks that I smuggled in, I settled in for something I had been longing to see for years.

Christopher Nolan isn’t a cuddly filmmaker, and I’m hot and cold on his movies. (I haven’t seen the controversial Tenet.) The Batman trilogy grew on me – I wasn’t a fan of some of the editing – but I’ve seen The Prestige and Inception several times, and I enjoy unravelling their various levels of reality each and every time. Time, time, time. I think Nolan may truly be one of those people (Alan Moore is another) who perceives time a little differently than the rest of us. He’s certainly obsessed with it, from Inception’s cutting back and forth and spinning top mystery to Dunkirk’s real life ticking tomb bomb of storytelling.

With Interstellar, time is the subject, a malleable dimension that speeds and slows, unlike the forces that transcend it: gravity and love.

Time is very much my own dimension for experiencing Interstellar. When I watch movies on TV, they may or may not stay with me. Unlike those who find cozy couch distractions comforting (most people), it’s nearly impossible for me to concentrate on watching stories on my TV – it’s why I prefer seeing movies in theaters and always will.

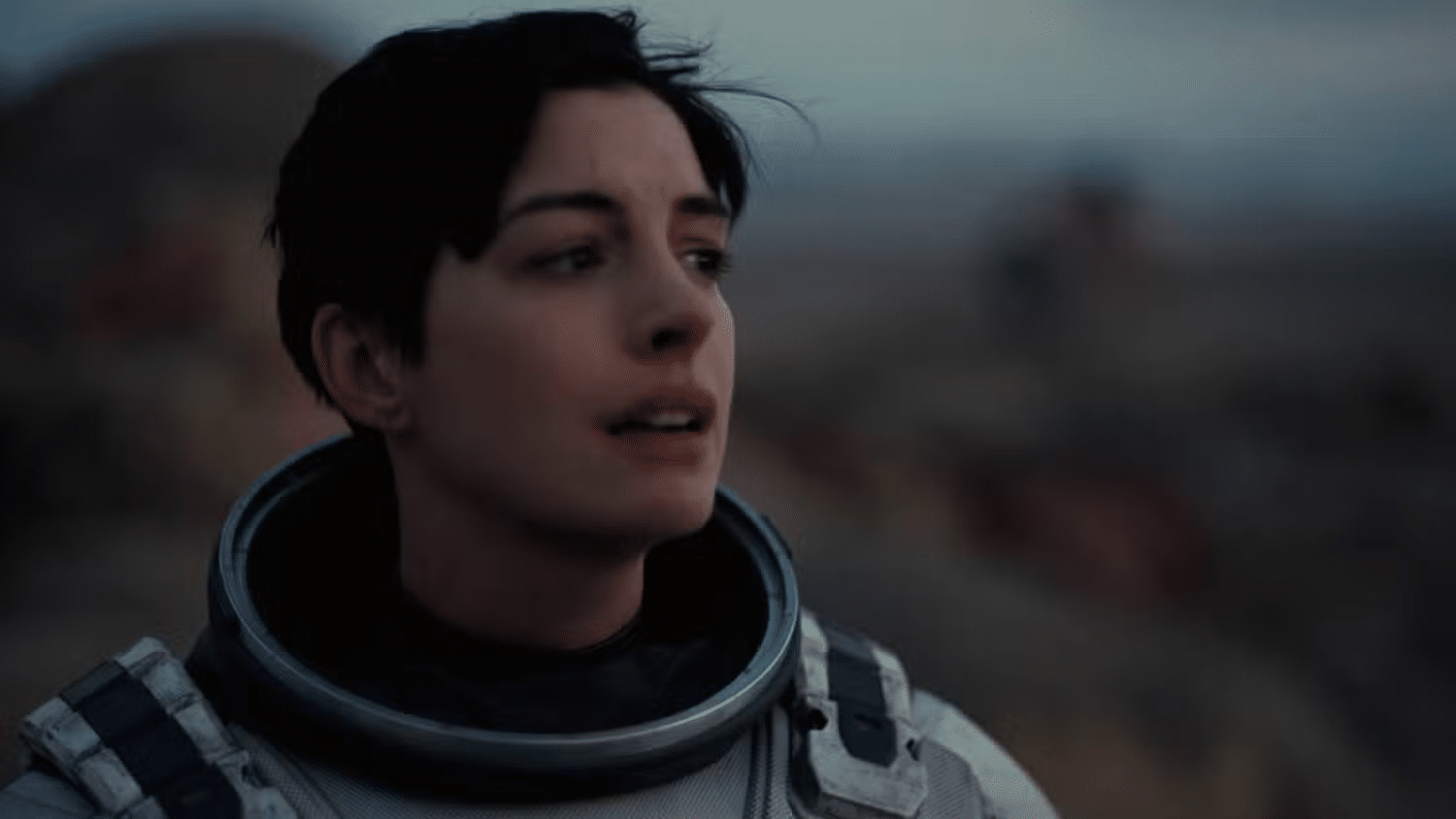

But Interstellar stuck with me. Anne Hathaway’s determined, hopeful face at the end pops into my mind frequently, a reminder that we can have hope and we can endure and one person can explore the majesty of the unknown and the power of love.

But let me backtrack a little to fill in the story: the film is set in an indeterminate dystopian future where resources – chiefly food – are dwindling, technology is faded and lies are the truth. From 2014’s viewpoint to 2024’s, Interstellar seems chillingly real and possible. A scene where a child is reprimanded for insisting the moon landings happened, and textbooks say it was a fiction plotted to drain Russian finances lands a lot differently today.

Matthew McConaughey plays Cooper, a widowed former pilot now a farmer, father to a son (I did not recognize Timothee Chalamet!) who is steered to follow in his father’s farming ways, and Murphy, a daughter who has a mind for science.

Through various plot twists, they discover that NASA still exists and has discovered a wormhole near Saturn – a wormhole planted by some unknown “They” who want Earth to find a new habitable world. To save humanity from this crumbling earth, 12 scientists have been sent through the wormhole to explore 12 possible planets in a single system. Only three are still viable: Cooper will pilot a spaceship to go through the wormhole to that far galaxy to find out if any of these planets work.

Cooper leaves Murph to save mankind, both of them in tears. The daughter is furious about being abandoned by her only surviving parent. Cooper knows he may never come back – the mission will take years and even more time may pass for the people left on earth than for the time-warping team.

But a strange thing is happening in Murph’s bedroom: books are falling off the shelves. At first they think it’s a ghost, but then they realize it’s a message from somewhere…a mystery unsolved when Cooper takes off.

What happens next involves scientifically plausible but unknowable matters: a black hole; a planet whose gravity is so strong that each minute that passes is a year for those in orbit; five dimensional space.

Cooper and his teammates – including Dr. Brand, played by Hathaway – explore two of the three potential planets, each event unfolding with a disaster of some kind. Fuel is exhausted, there is no way home….meanwhile, many, many years have passed on Earth and Murph is now a grown up Jessica Chastain and she is involved in the program to find a new planet. Cooper had continued to get updates from Earth via transmissions….but will they find a new planet, is the program even viable and most importantly, will father and daughter ever see each other again?

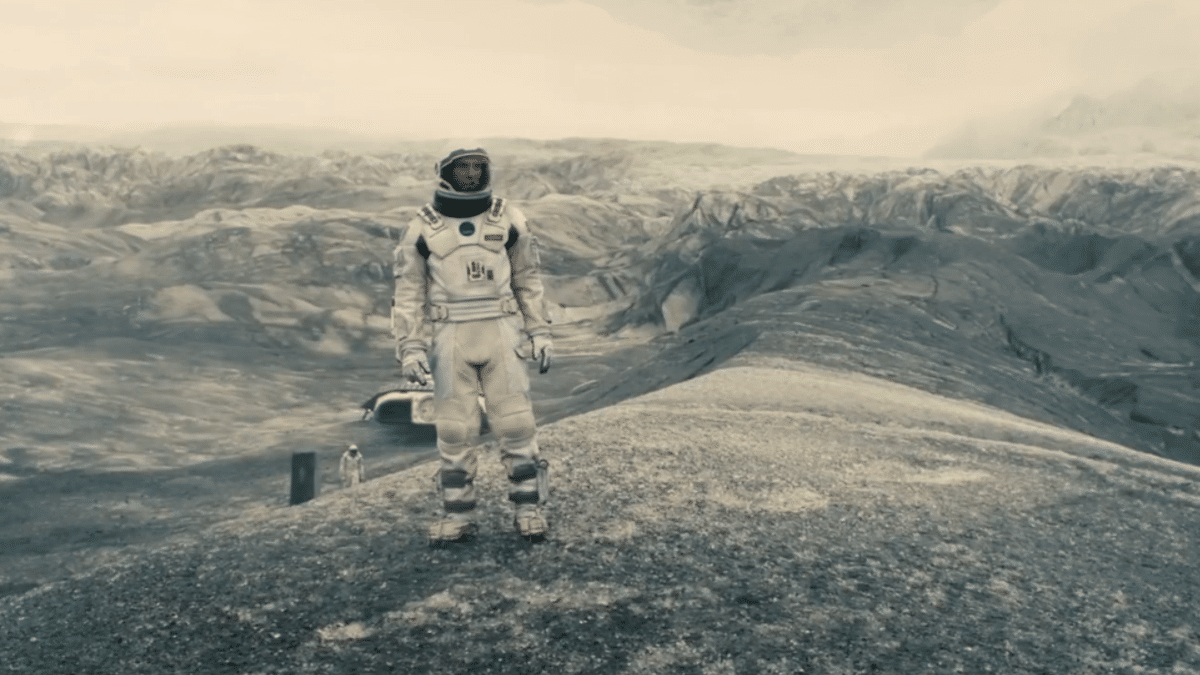

Interstellar is really a three way collaboration between director Nolan, cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema and composer Hans Zimmer – the latter two both Nolan regulars. It will come as no surprise that the film looks insanely good, and the frequent shots of a tiny spaceship against the vastness of space are stunning, as are the two major set pieces of the planet landings. The first is on a world covered by a shallow ocean – the image of the team in their spacesuits wading through water is instantly ominous and unforgettable. The second is an icy planet, shot on real icy terrain in Iceland. Zimmer’s score is a luminous thrum throughout, punctuated by occasional organ blasts that signify the most important moments.

When I said Interstellar haunted me, it was all these things that I remembered. The mystery of the three planets is an irresistible plot device, driven by the tragedy of separation and the noble struggle to save humans. There are a bunch of robots (AI is our friend, you’ll see) but cleverly non-humanoid ones, with distinctive characters, and played by the great Bill Irwin. They are tragic and brave and unforgettable in their own way.

But for me (and I think Nolan and his collaborator brother screenwriter, Jonathan Nolan) the real key is Dr. Brand. Cooper discovers halfway through the mission that Brand is in love with Dr. Wolf Edmunds, one of the three scientists whose planet may be habitable. This throws her desire to check on that planet into dispute with the rest of the team – after a speech where Brand states that love transcends time and space. She is aware that he is already likely dead, but “The tiniest possibility of seeing Wolf again excites me. That doesn’t mean I’m wrong.”

That Brand’s love for Edmunds is viewed with suspicion – while Cooper’s desire to save Murph is his one true goal – is one of the ironies that the film plays with. I admit that I’m a sucker for doomed love – both paternal and romantic. Maybe that’s the thing that made me love this movie so much. Nolan’s work is precise but often remote and so is the film – Hathaway’s immense quivering eyes and Chastain’s disdainful clenched jaw do a lot of the work, although tears were frequently flowing from McConaughey as well. Their emotions, set against the pristine filmmaking, make it clear what is at stake….and how desperate their mission is. And the payoff is cathartic. Cooper and Murph do reunite, in a wholly satisfying way.

One of my favorite episodes of the original Star Trek was “The Tholian Web” in which a dimensionally displaced Kirk floats with his transparency turned way up, with no one able to see him.

It’s a haunting and scary image – hitting right in our primal fear of not being seen or heard. It’s another thing that has stuck with me for many many years.

Interstellar radically ups that image with Cooper trying to contact Murph with the only means he has, a ticking watch (the central conceit of all Nolan films) and the frantic distress of a father trying to reach his daughter. For all his limitations, Nolan knows how to build a climax (think of the rocket launch in Oppenheimer.)

Another frequent complaint about Interstellar is that there is too much talk about love – a complaint also leveled against The Matrix movies. (The Edmunds romance plot twist is not even mentioned in the film’s Wikipedia page.) As I watched the film, it did not escape me that the phrase “wke grbage” did not exist in 2014 (what a happy time) and a movie where Anne Hathaway and Jessica Chastain save humanity (with a lot of help of Matthew McConaughey) would today be endlessly mocked by YouTubers who make a living off of hate. Luckily such concerns have not always existed, and perhaps someday they will exist less.

I think Interstellar is a perfect movie FOR ME, but I acknowledge it is not a perfect movie. There is a lot of science fiction mumbo jumbo – humans could not survive on a planet with such strong gravity that it warped time so severely, to name one thing. This is not a realistic documentary about black holes, so don’t expect it to be. And yes, it is clearly very influenced by 2001: A Space Odyssey, as well as many many SF classics that deal with the same themes. (Also, Titanic.) But they are good themes, and people should use them over and over to tell new stories.

It is rare for a movie to lodge itself in my memory the way Interstellar has; to be able to walk out my front door and see it on the big screen a few blocks from my house, be transported to its austere world building, and emerge into the real world again was a beautiful experience for me.

AND BAM! Back in the real world, I had a screening of Mufasa: The LIon King a few hours later!!! In 4DX!

But now we must go back in time again. It is 1993/4 and I work for the Walt Disney Company and I am co-editing the comics adaptation of The Lion King. This requires me to see the movie many, many times, starting with a rough animatic version. (I don’t think this is the case any more, with spoiler sites and whatnot. I can’t IMAGINE having the early access to Disney or any other studio stuff today that I had 30 years ago, when I would traipse in and out of the Animation Building at will and see all the movies that were in development.)

Anyway, that’s to say that after a while, I got sick of The Lion King. I knew it was great – one of Disney’s biggest successes ever, and a story that has become part of our culture. I saw the Broadway show early in its run, confirming that Julie Taymor is a genius and the songs are great and people love lions and they love this story. But I felt no need to revisit it for 30 years.

BUT I get invited to these 4DX screenings, and they are fun. I’ve written here about the life changing, fundament rattling experience that was seeing Twisters in 4DX. I knew Mufasa wouldn’t be that, but I felt maybe it was time to return to the world of The Lion King and maybe find out a bit more about where Mufasa came from.

As anyone who was ever a parent or a child knows, Mufasa is the father of Simba, the star of the Lion King, and voiced by James Earl Jones, he is kingly and wise indeed – until he dies a sad death in the Disney tradition. And that’s all we need to know!

Which is to say, the material that director Barry Jenkins (Moonlight!) and screenwriter Jeff Nathanson had to work with is a bit thin. Mufasa is a lion and he becomes king, and his adult brother turns out to be villainous scum. But how did he grow up? It turns out a lot like Simba in The Lion King.

There are early scenes of Mufasa with own dad and mom, Masego and Afia, head of their own pride. There is another tumultuous natural event that separates Mufasa from his kin – in this case a flood not a wildebeest stampede – and there is a foster brother named Taka with….an English accent? Hm. I wonder where this is going.

Taka’s pride sort of takes Mufasa in (with caveats) but then they have to escape another gang of very awful and mean WHITE lions (the leader is voiced by Mads Mikkelson so you know they are bad.) Mufasa (Aaron Pierre) and Taka (Kevin Harrison Jr.), are now young adult male lions, able to sing songs about their relationship but without their full manes. They wander around in search of a mostly likely mythical paradise, and then run into a brave lioness named Sarabi (Tiffany Boone), and a secretary bird named Zazu and a mandrill named Rafiki and…..look, everyone knew where this was going.

The screening was full of young kids who loved this movie, and yelped with joy whenever a reference to the OG Lion King was made. There’s a framing device that shows Rafiki narrating the story to Kiara, Simba and Nala’s cub, while Timon (Billy Eichner) and Pumbaa (Seth Rogan) joke around in annoying fashion, so there are many references to the OG.

I’m sure this movie will do well and please those who want more Mufasa. It was made in a photorealistic animated style, however, and….I find it impossible to get drawn into the story with this presentation. The lion cubs were very cute and everyone (myself included) went “awwwwww” when they did something adorable, and it looked really good in many ways. People like lions, I love cats of all kinds, so this had everything going for it on paper.

However, as someone who worked on the ORIGINAL Lion King……COMICS adaptation…I prefer the storytelling flexibility of “traditional” animation. It’s hard enough to make cartoon animals talk and sing….when they are photorealistic, your mind keeps wondering HOW does this work? I’ve been writing about The Uncanny Valley for as long as I’ve been doing The Beat, and while the style of Mufasa is on the upswing of the technique, my brain still doesn’t comprehend it on a deeper level.

In particular, I remembered a scene in the original where Scar points one claw at Simba. It’s an ominous move, easily accomplished in drawn animation (and with the great animator Andreas Deja’s masterful work on Scar). Such a gesture is impossible in realistic animation. There are a thousand cartoon gestures and expressions that made The Lion King a beloved classic that kids still watch 30 years later, that are impossible in a realistic style.

So I don’t know if it’s that Mufasa’s story was that thin or just that I couldn’t get into it. (Reviews are mixed.) Maybe it’s really just me. The children, raised on hours of staring at iPads, had no uncanny valley to traverse, and loved it.

A few more notes: the songs are by the now somehow wildly out of style Lin Manuel Miranda. An interesting recent piece in Vulture suggests that not using him for Moana 2 is Disney’s loss, Miranda was responsible for Disney’s biggest song smash of recent years “We Don’t Talk About Bruno,” and you might find him annoying but he’s still got it. I haven’t seen Moana 2, and I didn’t leave the theater humming any of Mufasa’s tunes, but the love ballad was good, and a song called (maybe) “Bye Bye” for Mikkelson clearly wants to tread into Bruno territory.

The film was shown not only in 4DX but in 3D – a duo I had never experienced before. The 3D was fine, and actually made the animation style more effective – perhaps the accepted artificiality of the 3D process removed a little of my inherent unease with photorealism. The 4DX was really minimal for this movie, and not needed. There are some scary (bloodless) lion fights, and some water spray but not one of the more notable outings for the format. I was not holding on to my seat in terror as I did with Twisters.

I’m sure that the animation style used on Mufasa can be applied judiciously for other purposes but call me when they figure it out. I did not see Jon Favreau’s realistic 2019 remake of The Lion King because, as I mentioned, I have used up all my Lion King tolerance for a lifetime – and also the original 1994 Lion King is a perfect animated movie. Mufasa is not bad, it’s just unimaginative. I’ve already forgotten it, and unless someone starts knocking books off my shelves on the other side of a wormhole to tell me about it, it’s likely to stay forgotten for me.

But why did Interstellar stay with me for years while Mufasa has already faded after a few hours? One is just far superior filmmaking, but some of it has to do with Nolan using so many practical sets and effects. It’s a real glacial lake for the water planet (a setting also used for A View to a Kill, Die Another Day, Batman Begins and Lara Croft: Tomb Raider), a real glacial mountain for the ice planet. The spaceships are large models. It’s a real house. It’s a real cornfield. Even on my small by modern standards TV screen, my mind knew this was real, and this made the jeopardy more real.

In Mufasa, we know that no matter how great computer animation is at rendering fur and water (but not yet wet fur), it’s not real. Combined with the conceit of talking/singing lions, it’s an uncomfortable experience, at least for this movie goer of a certain age. This being a Disney film there is no real violence, and a significant death happens so off screen you have to be told repeatedly what happened. The camera pans endlessly around various beautiful but imaginary valleys and mountains, but nothing sticks in your mind. Nothing is real and there is no danger….except hearing more bad jokes from Rogan and Eichner.

So that was Interstufasa. My takeaway: movie going is still a great thing to do. I am happy the children at Mufasa were happy. Going to the movies is a shared and powerful experience for people, and we mustn’t let Netflix take it away. Leave your house and you may find some wonderful things in the world.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·