Hank Kennedy | February 14, 2025

Photo of Martin Barker courtesy of Aberystwyth University.

Photo of Martin Barker courtesy of Aberystwyth University.“...comics are part of my and my children’s lives. And I now say this passionately: let us have as many of the things as we possibly can. In the face of the capital-calculating machine called Thatcherism which uses morality like murderers use shotguns, all the little things like comics matter.” – Martin Barker, Comics: Ideology, Power, and the Critics

Mass-media scholar Martin Barker passed away in September of 2022, yet I did not learn about his death until December 2023. The groups that I would have expected to offer him a eulogy or obituary were silent about his death. None of the major comics news and criticism websites wrote anything up about him. Neither did his former comrades in the UK Socialist Workers Party. His daughter, Rosie, did pen a heartfelt tribute in the Guardian, but that was it for mainstream media attention. This surprised and saddened me as a comics fan and political activist.

Barker was inspired to study comics from a debate impacting another media: film. In the 1980s, the UK was gripped by a moral panic over “video nasties,” horror films from the U.S. and Italy that were supposedly nothing but mindless violence without redeeming artistic merit. Critics like perpetual scold Mary Whitehouse argued that children especially needed to be protected from the nasties. Watchdogs critical of societal “permissiveness” thought that children would either model the violent behavior they had seen on film or that watching such films would desensitize them to violence. Anti-nasties campaigners frequently used emotive, charged language to make their points. Children were “violated” or even “raped” via exposure to videos. Today, these witch hunters would have said that their children were being “groomed.”

In response to the hoopla, Barker assembled the book The Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Arts, which was an attempt to counter a debate inflamed by the tabloid press and vote grabbing politicians. Barker worried that the Video Recordings Bill supported by anti-nasties activists would lead to “the biggest growth of censorship in this country in many years.” He viewed it as especially sinister to grant sweeping powers to censor to the UK Home Secretary “cloaked under the respectability of a bill designed to ’protect children.’” In a 1984 BBC2 documentary, you can see Barker (then a lecturer at Bristol Polytechnic) act as the sole voice of reason during the nasties debate. He accomplishes the rare feat of silencing Mary Whitehouse during a debate, however briefly.

If the arguments advanced by Whitehouse et al. sound familiar (and they should to anyone who remembers Fredric Wertham and Seduction of the Innocent), you are not alone. Barker thought so too, and he began researching the history of a similar moral panic: the anti-comics campaign in Great Britain. The result was A Haunt of Fears: The Strange History of the British Horror Comics Campaign, a predecessor/companion piece to David Hadju’s Ten Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare and How it Changed America. Barker's book, though, is much more explicitly political in its outlook and radical in its conclusions.

If the arguments advanced by Whitehouse et al. sound familiar (and they should to anyone who remembers Fredric Wertham and Seduction of the Innocent), you are not alone. Barker thought so too, and he began researching the history of a similar moral panic: the anti-comics campaign in Great Britain. The result was A Haunt of Fears: The Strange History of the British Horror Comics Campaign, a predecessor/companion piece to David Hadju’s Ten Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare and How it Changed America. Barker's book, though, is much more explicitly political in its outlook and radical in its conclusions.

A Haunt of Fears reveals the hidden hand of the Communist Party of Great Britain in condemning comics. The Communists had earlier assailed American culture, including comics as culturally imperialist. Comics, which the Communist Party publication Arena stated "portray fantasies of the future all fascist in character," were alleged to be a way that American capitalists were seeking to dominate the culture of the UK. Barker analyzed the comics of the 1950s and pointed out that EC Comics, the major target of anti-comics campaigns, had messages that should have endeared them to the Communist Party and other leftists but did not. In particular, Barker analyzed the EC story "You, Murderer" from Shock SuspenStories and finds that it was an attack on the McCarthyite conformity of the time period, not the endorsement that the Communist Party portrayed it as.

In his concluding chapter "The Forgotten Cause for Concern,” Barker argues that the racist and jingoistic war comics of the era were a far greater concern than the 1950s horror and crime comics. He uses the example of Battle Stories 4, which features the following dialogue from an American soldier: "‘I’ve got to do these Commies in – not only for myself, my buddies, my platoon, and my company, but for ... my girl, my folks, my home, my neighbors, my country. I've got to do this job right now for my way of life!" The GI continues, "I'm just an American soldier. I’m just a guy who'll keep on trying to make the Reds pay for the evil they have visited upon mankind!" Barker found it pitiful that through their focus on horror and crime comics, the Communists missed the "horrifying normality" of war comics.

Barker's book began a nearly two decade period of study of the comics form. In a 2002 article for the International Journal of Comic Art, Barker wrote that he had no particular love for comics before he started his research. He wrote that he “didn’t much read comics as a child ... and didn‟t at all as an adult, apart from a brief period of reading 2000AD.” Yet, despite this background, “comics, for seventeen years or so,” were the “focus of [his] intellectual life.”

Barker’s aforementioned political analysis came from his left-wing background. In the 1960s he was a member of the International Socialists. He maintained his affiliation when that group became the Socialist Workers Party in the 1970s. Barker wrote or co-wrote several articles for the Socialist Worker and International Socialism. Both A Haunt of Fears and The Video Nasties were first published by Pluto Press, then the Party’s avenue for publication. Rosie Barker wrote that her father was a “lifelong socialist.”

Barker’s aforementioned political analysis came from his left-wing background. In the 1960s he was a member of the International Socialists. He maintained his affiliation when that group became the Socialist Workers Party in the 1970s. Barker wrote or co-wrote several articles for the Socialist Worker and International Socialism. Both A Haunt of Fears and The Video Nasties were first published by Pluto Press, then the Party’s avenue for publication. Rosie Barker wrote that her father was a “lifelong socialist.”

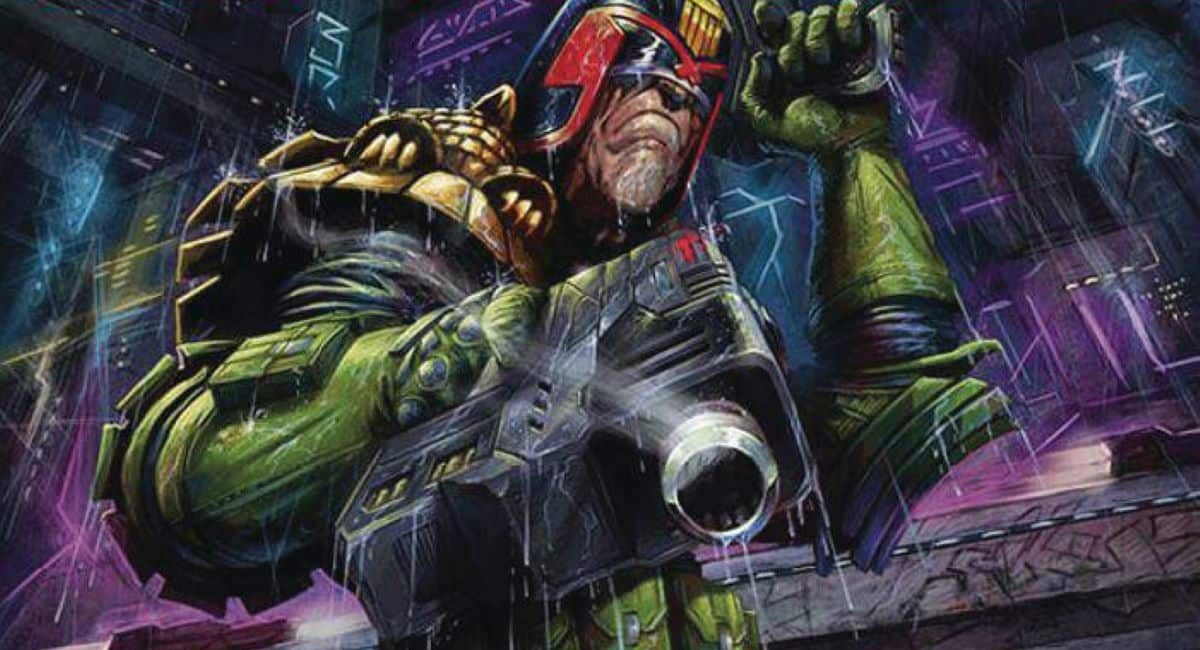

Although Barker was a proud socialist, his analysis differed greatly from that of his sometime comrades. The anti-comics viewpoint embodied by the Communist Party had not dissipated by the 1970s. In the Socialist Challenge, Janice Mills wrote that 2000AD offered instruction on “how to raise goons.” She viewed Judge Dredd as encouraging “an almost mystical view of the law” and said that the purpose of the series was “to produce fear of authority.” Over in the Socialist Worker, Dick Larkin claimed that Action and 2000AD were “poisoning young minds.” Larkin argued that with “Action and 2000AD we’re more than halfway there” to the sort of right-wing propaganda comics put out by the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile, featuring comics’ favorite waterfowl Donald Duck.

Barker went beyond these simplistic readings, which were reminiscent of the arguments made by the Communist Party creation of the 1950s, the Comics Campaign Council. Despite the variety of socialist and radical perspectives, seemingly all agreed about the worthlessness of comics and their reactionary character. Barker didn’t. He viewed attitudes like these as elitist. The Communists and Socialists who made them were embodying Trinidadian Marxist C.L.R. James’s critique that to see popular art as nothing more than a device to brainwash the masses was to see “people as dumb slaves.”

Barker’s books on comics were appreciated by comics fans themselves, certainly more so than the screeds published in Socialist Challenge and Socialist Worker, which would have been rejected on their face. In the Comics Journal #123, reviewer Dale Luciano called A Haunt of Fears “lively and readable” and “a fascinating book.” In the UK’s Escape a reviewer evaluated A Haunt of Fears as “a thorough, insightful study, which raises questions relevant today, not only to the controversies over pornography and video nasties, but also to renewed concern about the harmful effects of comics.” A writer for the same publication, Ed Pinsent wrote that Barker’s follow-up, Comics: Ideology, Power, and the Critics, which had a cover by EC great Jack Kamen, “will enhance and enlarge your comics reading experience.”

That follow up might be more difficult reading for Americans. For one, rather than focusing on EC Comics, the subjects are comics native to the UK. Titles like Action, Scream, the Beano, and Jackie might be well-known in the UK, but their fame has not traveled to the U.S. Even the references to Dennis the Menace are to the UK creation, not the American one. For another, Comics is written in a much more academic vernacular than A Haunt of Fears. As Barker collaborator Roger Sabin put it, Comics is Barker’s “least accessible but most academically influential work.”

The one American comic addressed by Comics is Donald Duck, via Barker’s overview of the left-wing cult classic How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart. Barker shares a common political goal with those socialist writers, but he is unafraid to point out their shortcomings. How to Read Donald Duck, in his estimation, presents comics wrenched out of historical context, ignores that multiple writers and artists worked on Donald Duck comics, and implies a shared Chilean national interest to resist American imperialism. Given the successful 1973 coup in that country, the last of those is the most obviously untrue. Barker concluded that “The Disney comics are neither ‘innocent’ nor ‘guilty’. They are too diverse and complicated for either.”

The year 1990 saw the publication of Barker’s final book length work on comics, Action: The Story of a Violent Comic. This was natural territory for Barker, as Action was itself subject to the sort of tut-tutting and moralizing that Barker had already written about. Future video nasties foe Mary Whitehouse attacked the comic as a symbol of the “permissiveness” leading to the UK’s national decline; the Sun referred to the title as “The Sevenpenny Nightmare.” Barker, as you can guess if you have read this far, thought differently. He viewed Action’s stories of desperate anti-authoritarian heroes as something relatable for readers dealing with “the world of punk, of post-1960s pessimism, of the rise of Thatcherism. If they weren’t on the dole, they probably would be soon. Authority was against them, they had few resources of any kind except a feeling of who and what they were. Action spoke for them.” He added that without Action, there likely would have been no 2000AD, concluding “for what Action did, in its brief life, let it be fondly remembered.”

The year 1990 saw the publication of Barker’s final book length work on comics, Action: The Story of a Violent Comic. This was natural territory for Barker, as Action was itself subject to the sort of tut-tutting and moralizing that Barker had already written about. Future video nasties foe Mary Whitehouse attacked the comic as a symbol of the “permissiveness” leading to the UK’s national decline; the Sun referred to the title as “The Sevenpenny Nightmare.” Barker, as you can guess if you have read this far, thought differently. He viewed Action’s stories of desperate anti-authoritarian heroes as something relatable for readers dealing with “the world of punk, of post-1960s pessimism, of the rise of Thatcherism. If they weren’t on the dole, they probably would be soon. Authority was against them, they had few resources of any kind except a feeling of who and what they were. Action spoke for them.” He added that without Action, there likely would have been no 2000AD, concluding “for what Action did, in its brief life, let it be fondly remembered.”

Although Barker wrote on his website that in the mid-1990s he had “left the field of comics studies, to others far better equipped” to handle the subject, that wasn’t entirely true. David Huxley claimed in his obituary for the International Journal of Comic Art that Barker was less motivated by his lack of ability than by the lack of funds available for comics research. Regardless of the stated reasons, it’s untrue that Barker entirely stopped writing about comics after the mid-'90s. He contributed a piece on a fascist fan of 2000AD’s Judge Dredd for the book Trash Aesthetics: Popular Culture and its Audience. He contributed two chapters to Pulp Demons: International Dimensions of the Post-War Anti-Comics Campaign – one revisited the British anti-comics campaign through the legislative wrangling over the Children and Young Person’s Harmful Publications Act; another reappraised Fredric Wertham as an “unhappy humanist.” His final writings on comics appeared in 2012, “Doonesbury Does Iraq’: Garry Trudeau and the Politics of an Anti-war Strip,” co-written with Roger Sabin, and “The Reception to Joe Sacco’s Palestine.”

Barker may have shifted his focus, but his work continued to explore pop culture and audience identification with a political twist, as best seen in his A Toxic Genre: The Iraq War Films, a 2011 survey of how films depicting that increasingly unpopular war evolved. His academic career took him from Bristol Polytechnic to the University of Sussex, before he settled at Aberystwyth University, where he retired as a professor emeritus in 2011. In 2003 he launched Participations, a journal of audience studies that continues today.

Was Martin Barker a comics fan? He himself didn’t think so. His daughter was instructed to respond to friends saying “Your dad reads comics” with “No, he studies them.” Nevertheless, there are certain tells that show Barker was more of a comics fan than he let on. EC great Jack Kamen was enlisted to illustrate the cover of Comics. Kamen’s “the Orphan” had been lovingly analyzed in A Haunt of Fears. Roger Sabin reported that Barker kept signed comics drawn by Swamp Thing great Steve Bissette. Whether an identified fan of comics or not, it’s clear that Barker had an affection for the medium, and yes, a love for certain titles.

It is unfortunate then, that some of his writing remains so unavailable. While A Haunt of Fears has remained available for readers, Barker’s other two books on comics, Comics and Action are long out of print. Action in particular fetches sky-high prices on Amazon and eBay. Video Nasties, also out of print, is priced on Amazon as though the book is made of gold. Perhaps with Barker’s passing, some enterprising and conscientious publisher will take the opportunity to reprint these important works.

My admiration for Martin Barker springs from a few places. For one, he showed that socialist media analysis is not synonymous with obtuse elitist. I would rather have one Barker than a dozen Larkins or Millses. For another, he took a brave stance against moral panics regarding protecting children from “harmful” media. As those of us in the United States deal with another rash of book bannings of titles ranging from Maus to Gender Queer, I hope that Barker’s scholarship can serve as a guide.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·