John Kelly | May 12, 2025

Mark Zingarelli in 2023. Photo by and courtesy of Dale Schmitt.

Mark Zingarelli in 2023. Photo by and courtesy of Dale Schmitt.Mark Zingarelli, a prolific illustrator and cartoonist whose work appeared on the cover of The New Yorker and pages of Weirdo comics, died on April 18th. He was 72. The cause of death was septic shock and endocarditis, according to his wife, Kate Alexander Zingarelli.

Zingarelli's 1990 floppy collection of autobiographical stories, Real Life (Fantagraphics).

Zingarelli's 1990 floppy collection of autobiographical stories, Real Life (Fantagraphics).At the time of his death, Zingarelli had been suffering from several long-term health issues, including liver, heart and kidney disease, that possibly originally stemmed from a head-on car accident he was involved in decades earlier. He was on dialysis, his aorta had been replaced, and he had trouble eating and walking.

"It was 1972, he was just out of high school, and had a head-on collision in an MG Midget and broke his jaw, crushed his ankle, messed up his knee...and there was also trauma to his liver, his spleen, his kidneys, his esophagus," said Kate Zingarelli. "There was deep trauma from the accident and over the years it just manifested. What got him in the end was bacteria and it went to his heart."

In a 2017 blog post, Zingarelli recounted the injuries he sustained from the accident: "My jaw was broken, having bent the steering column with the thrust of my forward momentum. Left ankle was crushed, a result of the clutch pedal and brake pedal driven together on both sides of my ankle from the engine coming back into the firewall. My right knee was also smashed pretty good from slamming into the small metal dashboard in the MG. Most serious of all for me, a young would-be artist with a hope for a future as an illustrator or cartoonist, was the crushed thumb on my right hand. No internal injuries, but that finding would prove to be false many, many years later. Stuff like that has a way of catching up to you."

For many years, Zingarelli had been an active presence on Facebook with his posts about some of his favorite things–food, vintage cars, antiquated art supplies, architectural curiosities and beautiful women–but as his condition worsened, he had quietly retreated from the public.

"Mark just didn't want people to know how sick he was," said Kate Zingarelli.

When the news of his death broke on Facebook, comments tended to repeat two common themes–his talent as an artist and how nice he was as a person.

"Mark Zingarelli was as good as they get," wrote the cartoonist Pat Moriarity in a DM to me. "Mark went far beyond comics with his excellent illustration work. He was one of the most 'in Demand' working illustrators I knew in the 1990s and 2000s. Zingarelli had great taste in women and food. You could tell by his art but also the stuff he posted on Facebook. Photos of classic beautiful actresses and models, and also food porn. Ha! One of his last posts was a video of an outright sinful sandwich/hoagie. It's probably still there if you go look."

***

Mark Alan Zingarelli was born July 11, 1952, at Wilkinsburg Hospital in Pittsburgh, PA. He was the oldest child of Dipierro Zingarelli and Vito Alan Zingarelli and had two sisters, Lisa Zingarelli and Laurie Slotterback, and a brother, Vito Zingarelli. His professional comics career began in the early 1980s in San Diego when he began submitting work to the Reader, the city's alternative newspaper. Zingarelli's career took off while he was living in Seattle, WA, and he created a restaurant review series for the alternative newsprint magazine The Rocket featuring his Eddie Longo character, who would review local establishments in form of a comic strip. He would later move back to the Pittsburgh area and become a visible presence in the local comics community there.

Zingarelli's "Eatin' Out with Eddie" strip ran in Seattle alternative magazine The Rocket. Courtesy Jesse Reyes.

Zingarelli's "Eatin' Out with Eddie" strip ran in Seattle alternative magazine The Rocket. Courtesy Jesse Reyes.Perhaps better know for his countless comics-stylized illustrations for national publications–Rolling Stone, New York Magazine, Entertainment Weekly, Sports Illustrated, Esquire, Time Magazine, Newsweek, Business Week, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The Wall Street Journal and many others–Zingarelli contributed artwork to Harvey Pekar's American Splendor and Dennis Eichhorn's Real Stuff and was a frequent cartoonist for Seattle's legendary pop culture magazine, The Rocket. In 1990, Fantagraphics published an issue of his autobiographical stories (plus one written by Eichhorn) called Real Life. His stories appeared in several issues of Robert Crumb's anthology, Weirdo, during the years it was edited by Peter Bagge (1984-86).

"In Seattle, I was contributing to local papers and for The Rocket, I was doing a monthly comic strip called 'Eaten' Out with Eddie,' a comic strip character who was a food critic, and that was pretty successful," Zingarelli told Jon B. Cooke in The Book of Weirdo (Last Gasp, 2019). "I fell into the artist community and made friends with Peter Bagge and Dennis Eichhorn, and many others...[Bagge] introduced me to this whole new world. He said, 'These stories are great! I'm going to put them in Weirdo!'"

"I published him in Weirdo because he was really good," said Bagge in an email. Weirdo, and its direct connection to Crumb, proved to be a key factor in Zingarelli's career growth.

"Crumb had touted me to a lot of people and he opened a lot of doors for me," he said in The Book of Weirdo. "He introduced me to Art Spiegelman and Harvey Pekar and I had established a reputation because of his support. I'm still grateful for that."

Zingarelli 's art from Harvey Pekar's American Splendor #15, 1990.

Zingarelli 's art from Harvey Pekar's American Splendor #15, 1990.Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Zingarelli continued to work in comics, but his successful illustration career took center stage. There was a time in the mid-1990s when his illustrations seemed to be in just about every national publication.

"I was forced to pull back from the comics work because I wasn't making any money doing it, because I wasn't fast enough or it took me longer to draw, and I had a tendency to labor over the material," he said in The Book of Weirdo. "Comics were paying unbelievably low page rates, as low as $50 a page, which I could get $2,000 for the same work from The New Yorker, where Art Spiegelman had gotten me on board as an illustrator, along with a number of other cartoonists/illustrators."

Zingarelli told me, and others, that his prolific illustration output led to strained relations with Crumb, who, Zingarelli felt, wanted him to focus on comics.

"[Crumb] presumed that I wasn't being serious about doing comics because I had to concentrate on paying work," he said in The Book of Weirdo. After an uncomfortable encounter in the early 1990s where Zingarelli said Crumb called his illustration career a "waste" and a "shame," their relationship ended. "It was as if I had disappointed my father."

While he utilized several classic styles, Zingarelli is primarily known for the precise, bold brush line work that reflected his love for EC comics and 1950s advertising art. His use of the brush came as a result of developing carpel tunnel early in his career. In his youth, he was a fan of MAD magazine, Famous Monsters of Filmland, Superman, Batman, Nancy comic strips, Jack Kirby's art, and war comics.

"Like a lot of kids, I quit reading comics at a certain age and my interest didn't start again until my first year of art school when a friend of mine took me into a head shop where there was a revolving rack of ZAP Comix," he said in The Book of Weirdo. "I had never seen anything like that...I had never heard of Crumb or known anything about the underground group of artists but, after that, I became a fan who searched out these comix because I was drawn to Crumb's style."

In the 1990s, hhe began employing a Pop Art style for many of his magazine illustrations that was reminiscent of Roy Lichtenstein's comic panel artwork. It was an approach he used for many national magazine covers and illustrations; countless other began doing it too.

"At the time, there were really only two of us doing that type of illustration work–me and Lou Brooks," Zingarelli told me a few years ago. "Then a lot more people started doing it."

Kate and Mark Zingarelli on their wedding day in 1989. Courtesy Kate Alexander Zingarelli.

Kate and Mark Zingarelli on their wedding day in 1989. Courtesy Kate Alexander Zingarelli.In 1987, while living in Seattle, Zingarelli went on a blind date with Kate Alexander and the two married in 1989. Soon after their wedding, the Zingarellis moved to Stanwood, WA, a small town about an hour north of Seattle. What they encountered there was a troubling story Zingarelli recounted in an eight-page comic for Mother Jones magazine in 1994, called "God's Country." The Zingarellis found themselves living in a community where the local public school district had been infiltrated by a religious right contingent from a large local charismatic church called the Camano Chapel. "God's Country" details the efforts by the Zingarellis and a few other families made to restore the rule of Separation of Church and State to their school district. It's a powerful piece.

Zingarelli's 1994 cover story for Mother Jones that recounted their effort to restore Separation of Church and State to their local public school district.

Zingarelli's 1994 cover story for Mother Jones that recounted their effort to restore Separation of Church and State to their local public school district."Mark and I had to have some serious conversations, between us and with supporters, as to whether we wanted to do this [story]...and put it out there nationally," said Kate Zingarelli. "There were only, maybe, six families in the whole city that a Stanwood and Camano Island that ever read Mother Jones, but it was quite the controversy. And it forced people to look at the power that the Camano Chapel had."

Member of the Camano Chapel served on the school board and instituted an "abstinence-only" sex educational curriculum. Outside speakers were brought into the schools and delivered Creationists beliefs–man existed at the same time as dinosaurs, the Earth is only 4,000-years-old–to students. The ACLU and the National Center for Science Education became involved; following the publication of "God's Country," the majority of the school board members were voted out or left their positions.

"I can never drive past Stanwood, WA, without remembering the ordeal he and his family endured there," said cartoonist Jim Woodring.

A career highlight came in 1994 when Zingarelli produced a cover for The New Yorker magazine, under editor Tina Brown and art editor Françoise Mouly. He also published many illustrations for the magazine during that era.

Zingarelli's New Yorker cover, 1994.

Zingarelli's New Yorker cover, 1994.A few years after their time in Stanwood, the growing family moved back to Zingarelli's hometown of Irwin, PA, just outside of Pittsburgh.

"He wanted his children to have the experience of growing up with family all around, like he did," said Kate Zingarelli.

In Pittsburgh, Zingarelli established himself in the local comics community and often participated in a regular comics salon that was run out of an Oakland comic shop, Phantom of the Attic. Other regulars in the drawing sessions included the late Ed Piskor, Jim Rugg and Tom Scioli, all of whom were in their early to mid-20s at the time.

"I have no idea how he learned about us but he started coming to our Wednesday get-togethers on new comics day, then down the street for coffee and to talk shop," recalled Rugg. "Mark fit right in too...he seemed to love hanging out and talking comics. A new issue of [Charles Burns'] Black Hole came out one week, and he was excited and so was I...Mark was so surprised that we knew Burns' work and were into it. It was a great night. Two generations celebrating an awesome cartoonist. I'm glad I got to know Mark. He was very positive. He didn’t judge us like we were kids or anything. I think he appreciated finding some people who respected the art form and we were happy to share that energy and ideas with a guy who was there and had done so much. Great talent. Wonderful human."

***

Zingarelli was a great storyteller and many of his earlier comics, which appeared in Real Life and elsewhere, were autobiographical or fictional ones he wrote himself. It's no surprise that an early ambition was to be a fiction writer. As of this writing, his blog was still active and is filled with many vivid personal stories, images and observations.

"At one point, I was writing a lot and submitting short stories [to magazines] that would be rejected, and then I didn't know what to do with stories," he said in The Book of Weirdo. "And then it came to me–'Why don't I just illustrate these myself?'"

During the later part of his comics career, he mostly worked with other writers for his stories. Beyond collaboration with autobiographical writers like Pekar and Eichhorn, he contributed to a 2015 series of comics called Chutz-Pow!, which was done for the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh. In Chutz-Pow!, Zingarelli and other artists set the stories of Holocaust survivors in comic book form. A 2014 collaboration with the late writer Joyce Brabner, Second Avenue Caper, told the true story of a group of New York City artists and activists during the AIDS crisis of the early 1980s.

"I did a lot of comic strips for a lot of magazines, but few were drawn from my own storytelling," he said in The Book of Weirdo. "On reflection, I became too obsessed, too much a perfectionist. And all it did was put me in a procrastination mode that haunted me for years. Of course, I was also raising three daughters and trying to make a living as an illustrator for those years as well. They were not unproductive years, except in doing my own comics stories."

His family was extremely important to him.

"Mark was part of a large extended Italian family of grandparents, cousins, aunts, and uncles, too numerous to even begin to name," said Kate Zingarelli. "He was exceedingly proud of his family and his Italian heritage. Anyone brave enough to ask him about his family was in for a treat and great stories."

Zingarelli had a lifelong love of drawing and was encourage to do so by his father, Vito.

"My father was my first art teacher though he wouldn't have considered himself any good," he said in a 2011 interview. "Never stop learning from the experience [of drawing]. A lifetime isn't enough time to do all of it so enjoy the time you have and make the most of every second you are able to draw."

Like his father, Zingarelli passed along his love of art to his own children.

"I would spend endless time circling around his studio or sitting on the stairs, watching him work," said his daughter, Zea Elkins, in a Facebook post. "He would eventually get annoyed and tell me to go find something to do. But he never missed an opportunity to explain what he was working on or share an insider tip."

Essentially self-taught, Zingarelli took some summer art classes as a boy and after high school briefly enrolled in Pittsburgh's Ivy School of Professional Art.

"I learned to spec type for typesetting and had a marvelous figure drawing instructor [there]," he said.

Zingarelli's Laugh Finder from his childhood Cartoonists' Exchange instructional materials.

Zingarelli's Laugh Finder from his childhood Cartoonists' Exchange instructional materials.In his youth, he enrolled in the Cartoonists' Exchange of Ohio's mail order instructional course and studied those materials. He held on to them (and many other things) too. His personal collection of those artifacts were included in the 2016 "Draw Me!" exhibit I organized at Pittsburgh's The ToonSeum, a small museum of comics and cartoon art. As part of the show's programming, Zingarelli gave a talk to young cartoonists about the step-by-step process for using such forgotten art supplies as Zip-A-Tone, Letraset and Rubylith. He also collected many books of vintage clip art catalogs, deceased artists' swipe files and other ancient advertising and artist materials. After studying art and filmmaking at the University of Pittsburgh, he managed an art supply store in San Diego.

"He never missed an opportunity to add to his collection of supplies," said Kate Zingarelli. "Mark never met a paintbrush, pen, or pencil that he didn't require for some project."

"In art school, I had recently been recently introduced to the technical pen and I recognized that Crumb was using the same pen," Zingarelli said in The Book of Weirdo. "While I enjoyed [Crumb's] stories, I was more captivated by his drawing style. That's when I started to do comics-style work."

***

A 2017 car wreck drawing by Zingarelli. Courtesy House of Zing.

A 2017 car wreck drawing by Zingarelli. Courtesy House of Zing.In 2017, Zingarelli began posting on Facebook some of the drawings of car wrecks that he had been making.

"Wrecked cars have been a fascination of mine for much of my life," he wrote in a blog post, adding that at the time he began drawing them, he wasn't consciously doing them as any response to the serious car accident he suffered as a teenager that possibly contributed to his later health problems. In the post, he talked about the orthopedic surgeon who worked on him following the accident.

"I remember that he was first person who actually told me how lucky I was to have survived that accident," he wrote. "He told me he knew of my artistic aspirations and told me that I had been given a second chance, and that I should go out and be that artist that I dreamed about....Even today, when faced with setbacks of any kind, or losses that seem unbearable, I remember that I was given a second chance. That I didn't die in a car wreck at 19."

***

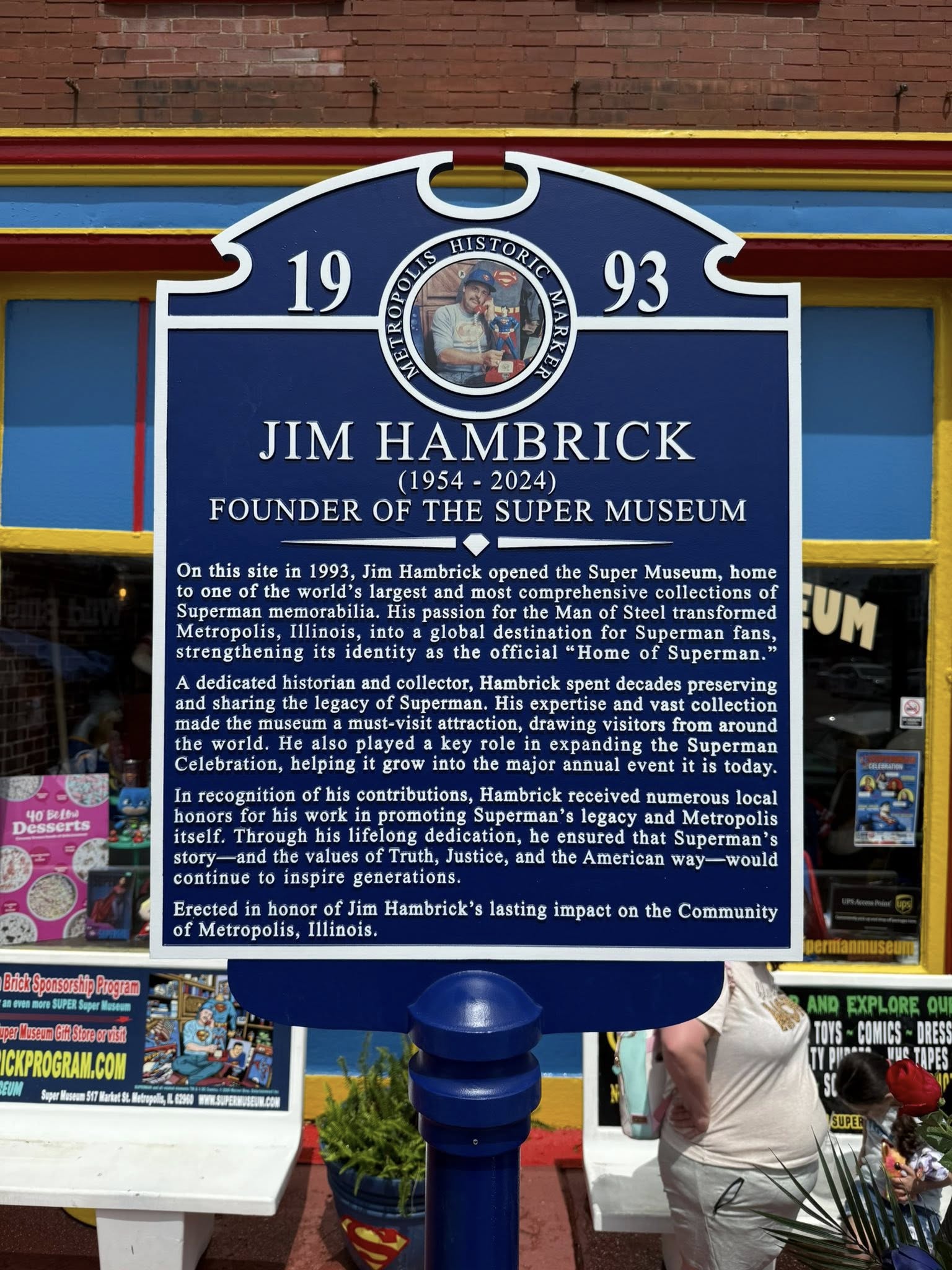

The Zingareli's home after the 2024 fire.

The Zingareli's home after the 2024 fire.In 2024, as Zingarelli's health continued to decline, the family was dealt another blow. On September 21st, an electrical fire caused massive damage to the Zingarelli's home in Irwin. No one was injured in the blaze, but the entire interior of the house was destroyed.

"The fire gutted the living room and the bedroom above it," said Kate Zingarelli. "It went into the attic and so they had to fight the fire in the attic. So the whole second floor was damaged from water and pulling the ceilings down."

Water seeped down the walls, which eventually led to mold throughout the house. The only part of the house not damaged by the fire or its aftermath was Zingarelli's studio, which contained his artwork and archives.

***

Zingarelli is survived by his daughters, Jessie VanSickle, Zea Zingarelli-Elkins, Stella Hutson and Isabella Zingarelli, several grandchildren, his brother and sisters, and his wife, Kate. A previous marriage ended in a divorce in the mid-1980s.

***

In the space below, some who knew and worked with Zingarelli share some memories about him.

***

Zingarelli in 2023. Photo by and courtesy of Dale Schmitt.

Zingarelli in 2023. Photo by and courtesy of Dale Schmitt.Robert Newman

art director via The Rocket, Entertainment Weekly, The Village Voice, Details, and others

I first met Mark Zingarelli when we were both in Seattle, working at The Rocket magazine, where we published his amazing "Eatin' Out with Eddie" illustrated local food reviews. But we actually got friendlier and did more work together after I moved to New York City and started art directing at various newspapers and magazines. Mark did assignments with me for the pages of the Village Voice, Entertainment Weekly, New York, and Details, among others, and his work was always beautifully drawn. He was always a joy to work with, but even more fun were the long, long phone conversations we had that were ostensibly about an assignment, but wandered off into tales and gossip of all kinds. He had a big personality and an even bigger heart. My favorite project with Mark happened in the early 1990s, when I had just been at Entertainment Weekly a few months. They wanted to run a four or six-page comic review of Nancy Reagan's memoir and had an in-house writer, but no artist. I called Mark in Seattle and offered him eye-popping money with the catch that he had to fly out to NYC the next morning and stay for a week. He was on the first plane the next morning, and spent the week holed up in a fancy hotel with the writer, working around the clock. The piece was a big hit, and we celebrated at a swank restaurant and ran up a huge tab. We laughed about that assignment (and the meal) for years afterwords. Mark was a great pal and a great comrade and I'll miss him a lot.

An undated photo of Zingarelli. Courtesy Kate Alexander Zingarelli.

An undated photo of Zingarelli. Courtesy Kate Alexander Zingarelli.Mary Fleener

cartoonist

One thing I've noticed in the last few days is no one, and I mean, no one, has a bad thing to say about Mark. There's a good reason for that. He was a gentleman, and a sweet man. I only met him one time, and that was in the late '80s at Pete and Joanne Bagge's house in Seattle. That was 1987. My husband, Paul, and I were on our way to go to Expo in Vancouver, BC. I was already a fan of his work that I'd seen in Weirdo. Mark had a distinctive style that was cartoon-like but had all the good things about comic art that grabbed my eye and my attention. I would call it "Ink Noir." He knew what CONTRAST was and, in my opinion, was a master of black and white. His cover for Denny Eichhorn's Real Stuff was perfection and he inspired me. After seeing that cover, it was tempting not to copy him.

The last time I was in Seattle was 1994. I had a show with Jim Woodring. My husband came with me. We had a great time. When we got to the airport to go home, it was raining buckets, as only it can in the Pacific Northwest. I was anxious about the flight, but then something happened. We saw Mark's art all over the airport! Big, huge reproductions! It was instantly recognizable. I forgot about the rain and my fear of flying.

Zingarelli and Rick Geary, ca. early 1980s. Courtesy Rick Geary.

Zingarelli and Rick Geary, ca. early 1980s. Courtesy Rick Geary.Rick Geary

cartoonist

I first encountered the Mark Zingarelli in 1982 in San Diego, where we both contributed our work to the city's alternative weekly paper, the Reader. His open, friendly nature immediately drew me in, and I found we shared a similar dedication to the pursuit of pen-and-ink illustration. As we got to know each other, I found that we also shared a fondness for pulp authors and noir movies, as well as all aspects of true crime. All this was reflected in the graphic stories we did for various comics anthology publications.

A few years later, after he had moved up to the Seattle area, my wife and I visited him there, and he gave us a tour of his favorite spots in the city.

Over the ensuing decades, we exchanged greetings and messages through email and Facebook, as he moved back to his childhood home outside Pittsburgh, and I moved to the wilds of New Mexico. During this time, he had become a familiar contributor to national magazines. When I visited Pittsburgh in 2016, he was kind enough to attend a presentation I gave downtown at the ToonSeum. There we caught up on our lives, relived our Reader days, and reaffirmed our admiration for each other’s work.

Zingarelli and Bill Griffith in Pittsburgh at a 2016 ToonSeum event, The original art for the Zippy strip in Griffith's hands depicts Scotty's Diner in Wilkinsburg, PA, Zingarelli's birthplace. Courtesy Kate Alexander Zingarelli.

Zingarelli and Bill Griffith in Pittsburgh at a 2016 ToonSeum event, The original art for the Zippy strip in Griffith's hands depicts Scotty's Diner in Wilkinsburg, PA, Zingarelli's birthplace. Courtesy Kate Alexander Zingarelli.Jon B. Cooke

comics historian

I probably maintained a connection to Mark Zingarelli the same way many did–via responding to his engaging Facebook posts. But, of course, I knew of his work for many a year and I loved his artwork and his lush inking technique. I held him in the same esteem as I did any number of artists unafraid to lay in the blacks and feather the details with their brushwork. Y'know, like Bernie Wrightson, Wallace Wood, Greg Irons, Dave Stevens... rich and mood-evoking. And boy, the Zing could do moody atmospherics! Comics noir…

And I grew to like the guy as much as I enjoyed his work. A really good egg, he was. And I was particularly happy to feature him in my Book of Weirdo, about his work for Crumb's humor mag, where most people were first exposed to this Zing guy. It was a long telephone interview (from which I derived his testimonial) and he didn't hold back his ambivalence about the comics life, and I was impressed with his forthright, self-deprecating candor. Mark recounted how Crumb championed his work at first and Peter Bagge would basically publish anything he submitted, and he and his first wife would have the Crumbs and Bagges over for dinner and they all got along fabulously. But then, after his new career as commercial artist was in full swing, there came Misfit Lit, a gallery showing of alternative cartooning. It was there Mark encountered a disappointed Crumb, who wouldn't make eye contact or talk, resenting Zing for focusing on actual paying work to raise his family after a divorce and not doing enough comics. Aline pulled Mark aside and said Robert had looked upon Mark as a protege. He never got over that disapproval.

Mark was enormously likable and, just before the pandemic hit, I embarked on a trip that included a stopover in Pittsburgh , where I spent time with Wayno, David Coulson, and the Zingman. The latter two and their charming spouses took me out to dinner, and the overall highlight was to spend an afternoon with Mark, endlessly chatting–on the record, as I recorded it all for a possible podcast– and damned if he wasn't as lovable as ever. But that low self-esteem was still there and I did my best to try to pump him up, suggesting we do projects together…something, anything…let's get you drawing comics again…He was such a great guy, so many loved him, and his "film noir on paper" was stunning work. It was a great day. I loved that guy.

See ya when I see ya, in that great diner in the sky, Zingster, where we'll talk about what American state had the best weiners (no contest, sez I, it's New York Style weiners, oddly only concocted in Rhode Island, celery salt and all). Maybe Eddie will be on the stool next to you and I know there'll be a '40s Plymouth or two parked out front, one with a smoking P.I. at the wheel...

Bruce Chrislip

cartoonist

I first met Mark Zingarelli at one of Peter Bagge's parties in Seattle in the mid-1980s. He was very friendly and easy to talk to. What you'd call a "people person." In conversation, it turned out we had something in common. He'd grown up around Pittsburgh and I grew up in a suburb of Youngstown, Ohio which was not too far away. My brothers and I watched Pittsburgh television programs all the time and I was familiar with Bill Cardille on Chiller Theatre broadcast on Saturday nights (or, as they called him in the intro, "Chilly Billy Cardilly") and Studio Wrestling on Saturday afternoons. Mark told me that one of the wrestlers on the latter show was his uncle–Jumping Johnny DeFazio! How cool was that?

Zingarelli loved to draw cars, as seen in this story from Real Life, 1990.

Zingarelli loved to draw cars, as seen in this story from Real Life, 1990.And Mark really owned that yellow 1961 Cadillac that appeared in his Real Life comic book (above) published by Fantagraphics in 1990. One wintry evening while departing from a party at Peter Bagge's house, Mark demonstrated how he utilized a small spray can to de-ice the door lock. As he started the car to warm it up, a big cloud of smoke blew out of the exhaust. My wife Joan asked, "How does that ever pass the state emissions tests?" To which Mark replied, "It doesn't have to. Cars this old get an exemption!"

Sometime in the late 1980s, Mark started drawing a restaurant review comic strip for The Rocket featuring his alter ego Eddie Longo. It was called "Eatin' Out With Eddie" and specialized in publicizing small family-owned restaurants, cafes and diners. Real blue collar food. Somewhere in this time period. Mark even portrayed Eddie Longo on one of the local Seattle radio stations. He really got into it, emphasizing his native western Pennsylvania accent by referring to groups of people as "younz" and "stuff like 'at 'ere" while rhapsodizing about some of his favorite restaurants. Sometime during the hour, Peter Bagge disguised his voice and called in to ask if Eddie ever went to delis. (At the time, Pete's wife Joanne was running the Fill Yer Belly Deli on the east side of Seattle).

There was always lots of activity on the local comics front back then. Sometime around 1988 or 1989, a local gallery brought in a traveling cartoon art exhibit called The USA-USSR Cartoon Exchange which featured the work of both American and Russian cartoonists. Several of the Russian cartoonists were visiting Seattle in conjunction with the show. I remember trying to converse with some of them but their English was limited and my Russian was non-existent. Mark, however, bonded with the cartoonists and actually spent a night out drinking vodka with them. He tried to keep up as best he could, but it was a lost cause and he later told me that he ended up with the worst hangover of his entire life.

Hearing about Mark's passing brought back lots of pleasant memories of a Seattle comics scene that is now long gone. I consider myself lucky to have met him and saddened that I won't see him again. He was a great cartoonist and a great guy.

Zingarelli loved to draw monsters. Some classic horror movie faces, ca. 2022. Courtesy House of Zing.

Zingarelli loved to draw monsters. Some classic horror movie faces, ca. 2022. Courtesy House of Zing.Wayno

cartoonist

Mark Zingarelli was an unsurpassed illustrator and cartoonist, and a beloved member of Pittsburgh's arts community.

In 2017, I had the privilege of presenting him with the Nemo Award from Pittsburgh's (now defunct) ToonSeum. My introduction (with slight updates) follows:

Zingarelli and Wayno in Pittsburgh. Image courtesy Kate Alexander Zingarelli.

Zingarelli and Wayno in Pittsburgh. Image courtesy Kate Alexander Zingarelli."An award doesn't elevate the status of the recipient. Rather, the significance and legitimacy of any award reflect the quality of those it recognizes. Tonight, the Nemo Award is greatly enhanced by the artist being honored.

"Since 2008, a select group of artists have received this award. Among them are Jerry Robinson, Ron Frenz, Trina Robbins, and Bill Griffith.

"This award goes to an artist who has advanced the art of comics and graphic storytelling for over forty years. His work is honest and compelling, informed by his experiences as a loving husband and father, a devoted friend, and a mentor to many other artists.

"In addition to being a master of his craft, he's generous, gregarious, and kind-hearted: our friend and colleague Mark Zingarelli."

There's not much to add other than the fact that Mark will be missed by the cartooning community worldwide and by those who knew and loved him.

I treasure the many hours spent with Zing discussing comics, music, food, and Italian families over coffee, hot dogs, or "sangwidges."

A Rocket cover from 1989. Courtesy Jesse Reyes.

A Rocket cover from 1989. Courtesy Jesse Reyes.Peter Bagge

cartoonist

There was 4-5 year period when I was very close friends with Mark Zingarelli. This would be in Seattle in the mid to late '80s. His food review comic started appearing in the Seattle Rocket at the time I moved out here, and I was amazed at how skilled he was, so I immediately tracked him down. I'm sure that anyone who knew him could tell you what a friendly and gregarious guy he was. Mark liked to cook, as does my wife Joanne, so we went to each other's houses for dinner constantly. Mark also once did a rave comic review for the Rocket about the deli Joanne co-owned at the time–after which the then-editor of that mag accused us both of "corruption" and "unprofessionalism" once he made the connection. Ha! Mark and I even took up tennis briefly (Seattle was filled with unused tennis courts back then), but that ended when Mark developed a deteriorated disc in his spine. I used to taunt him and call him a pussy every time he complained of the pain in his back. Turns out he could have been paralyzed if we had kept playing. Oops!

Our relationship took a difficult turn after Mark got divorced from his first wife, which understandably left him traumatized. We tried very hard to remain friends with him, but he seemed determined to cut all ties with us and move on, which he did. We still had many mutual friends, so I would occasionally would get updates about him, but we never communicated directly ever again. It never made any sense to me. Oh well. RIP.

Zingarelli loved to draw wrestlers. And women. Courtesy House of Zing.

Zingarelli loved to draw wrestlers. And women. Courtesy House of Zing.Bruce Simon

Cartoonist

I only knew Mark online but an unfailingly nicer and more positive guy would be hard to find. He never failed to impress with his versatility; not many cartoonists straddled the underground and commercial spheres like Mark did and resolutely remain his own man. I remember walking past a newsstand in 1994 and being knocked out by his New Yorker cover of beach goers raising their umbrella like the Stars and Stripes at Iwo Jima, a high point of any cartoonist's career. A great and generous guy who'll be sorely missed.

Zomgarelli loved to draw women. Cover for a Penguin Books publication, The Last Manly Man by Sparkle Hayter, ca. 2001. Art direction and image courtesy Jesse Reyes.

Zomgarelli loved to draw women. Cover for a Penguin Books publication, The Last Manly Man by Sparkle Hayter, ca. 2001. Art direction and image courtesy Jesse Reyes.Jesse Reyes

art director via The Rocket, The Village Voice, Penguin Books and others

A memory of Mark that comes to mind is a fairly recent though trivial one, but it kinda captures "him." A little background: Most of us who were Seattleites at any given time—homegrown like myself or one-time transplants like Mark—have a deep affection and an affinity for Seattle's beloved, fast-food restaurant chain, "Dick's Drive In." An unapologetically stuck-in-time holdover from the late-1950s. Small menu, but amazingly consistent over the decades—notably its burger—with its distinctive sauce as its signature characteristic. It's allowed the small chain to not only survive against the fast-food national-chain burger behemoths, but to thrive (adding five new locations to their original six, ca. 1954-1974, in just the last 14 years—an explosion of growth by their standards), retaining not only their core menu, but their 1950s-to-early-1960s "Googie" building structures and distinctive retro signage, and migrating that look to its newer locations.

But if, like me, you've moved away from Seattle, other than the occasional visit requiring a pilgrimage, you are out of luck in getting a comparable "Dick's" fix. Maybe if you moved to SoCal you could adapt to fellow Mid-Century holdouts In-N-Out Burger or Bob's Big Boy, but otherwise nada.

That is, until Mark made a remarkable culinary discovery. About five or six years ago we were talking, reminiscing about the old days in Seattle and the things we missed (I live outside of New York City and Mark had returned to his hometown south of Pittsburgh) when Mark said, "Guess what? I've figured out 'Dick's' burger sauce!" Call me flabbergasted, it was like revealing he had found the Holy Grail at a junk store. Under cross examination, he testified he'd been experimenting for years trying to get it right. He insisted that not only was it accurate, but the recipe held up to scrutiny after multiple tries. He passed it along to me—in deference to "Dick's" and their IP, I will not reveal it here—and I immediately tried it out that night. Mark was spot on. I was transported to my youth and many happy visits to "Dick's," a welcome and needed respite after many a midterm exam, art school overnight (the Capitol Hill "Dick's" was two blocks from my art college) and Rocket magazine deadline. I was amazed!

Last summer I was talking with my boyhood chum, the Hip Hop DJ and record label pioneer, "Nasty" Nes Rodriguez (1961-2025), a Seattle-expat living in Los Angeles. He too expressed longing for "Dick's Drive-in" and its unbeatable burger, despite SoCal's own, aforementioned native fast-food icons. I told him of Mark's recipe, and passed it along. Nes eagerly rushed out to gather ingredients and try it for himself. I can happily report that Nes, like myself, achieved the same result—a much-missed taste of home.

Mark's comics alter-ego, neighborhood-joint foodie "Eddie Longo," would be proud.

A 1990s issue of the Seattle Star featuring Zingarelli's work. Courtesy Jim Blanchard.

A 1990s issue of the Seattle Star featuring Zingarelli's work. Courtesy Jim Blanchard.Wayne Wise

writer/collaborator via Chutz-Pow!

I met Mark Zingarelli while working at Phantom of the Attic Comics in Pittsburgh. While I know I had seen his work prior to this, this was when I discovered the breadth of his remarkable career as a cartoonist. Over the years we developed a genuine friendship. I had the profound honor and privilege to collaborate with him on several of the Chutz-Pow! stories, published by the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh. His wonderful artwork brought to life my words and the lives of Holocaust survivors. Working with Mark was an education. Though I had written for comics before, Mark had more of an innate understanding of text on the page and pacing. His edits were thoughtful and he always talked to me about the choices he made. The stories we told were stronger for his input. Mark was an example of gentle and affectionate strength of character. His sense of humor and his fierce love for his family and friends informed his consummate professionalism. He and his wife, Kate, his daughters Zea, Bella, and Jessie became family. He was, quite simply, one of the single best human beings I have ever known. Rest in peace, my friend.

Zingarelli's art for a story in Chutz-Pow!, a comic series done for the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh. Story by Wayne Wise.

Zingarelli's art for a story in Chutz-Pow!, a comic series done for the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh. Story by Wayne Wise.Marcel Walker

cartoonist/collaborator via Chutz-Pow!

There are two complementary modes in which I tend to think about Mark Zingarelli: Mark as an artist, and Mark as a person.

Having collaborated with him professionally several times over the years, including as a ghost-penciller and as his editor, I've analyzed Mark's artwork time and again and come to appreciate elements of his work that also reveal his character: He was meticulous in his process and really thought through every element of what went on the page and where it belonged. His understanding of anatomy and body language displayed keen social observation. Mark was also unafraid to incorporate new skills into his practice and was just as adept with traditional tools of the trade–paper, pencil, ink, rulers, and light boxes–as he became with digital tools. Witnessing his flow from drawing table to scanner to image editing software was an art lesson for any aspiring creative.

Mark was the first and, to date, the only graphic-prose artist I've met who lettered his comics artwork before doing the drawing. I saw pages of his narratives composed with every panel containing word balloons and captions, perfectly in place, and nothing else. The effect was ghostly! He labored over the lettering with precision, which speaks to his commitment to detail nearly as much as the element of his art which I assert truly defined him…and that's his textures.

Through the years, Mark had been around and seen quite a bit, and possessed a low-key cosmopolitan air which came through when he spoke about work, family, the places he'd lived, his cultural reflections, and more. His verbal stories were full of rich texture, so it's only natural that his drawn ones were too—gorgeous, varied textures throughout every sequence of every page, distinguishing water from rocks, earth from sky, tree bark from bricks, and a multitude of fabrics from one another. If you strip away every other component of his illustrations, it's his textures, rendered in exacting ink lines, that most reveal his thoughtful understanding of the world.

The depth of Mark's humanity was in the details. When Mark saw you, if he liked you (and he didn't like everyone—he was relatable in that way), you could hear it in his voice immediately. And if he loved you, it was unmistakably felt. Mark provided one of the finest examples of affectionate masculinity that I've ever personally witnessed. There aren't many men in my life who've actually kissed me with paternal warmth, particularly men from earlier generations than mine. But Mark did, every time we met or said goodbye, and I already miss that. It was an expression of love clearly born from the traditions of Italian families, and I was humbled that he extended his family's warmth to me.

The texture of Mark's masculinity was gritty enough to sand down a pencil, smooth enough to glide knowingly through conversations with peers, and soft enough to embrace loved ones with joy. Mark embellished my artwork and my life, and I perceive the world in more detail because of him.

Zingarelli's poster for a The Pirates of Penzance poster for Seattle's Fifth Avenue Musical Theater, ca. late 1980s. Image courtesy and art direction by Art Chantry.

Zingarelli's poster for a The Pirates of Penzance poster for Seattle's Fifth Avenue Musical Theater, ca. late 1980s. Image courtesy and art direction by Art Chantry.Art Chantry

art director via The Rocket and other projects

I've known Mark Zingarelli for around 40 years. He was a great friend and collaborator and all-round good fella. He had a great garbage mind as well–a lover of common-man foods and weird little diners, detective noir paperback novels, pro wrasslin', old Cadillacs, you know–all those great contributions from America to the entire world. KULTURE!

I met him through one of my early stints as art director for The Rocket magazine, where he developed some of his styles working virtually for free. I also tried to get him to collaborate on poster work as much as I could. I discovered he had a love for old musicals! I was working on a series of posters for the Fifth Avenue Musical Theater company, presenting old warhorse material like Oklahoma, Sound of Music, Unsinkable Molly Brown, Mame–that ilk. I wanted the posters for the plays to look like those old newspaper ads for movies back in the 1940s. I called up Mark and he knew exactly what I was talking about–and he adored crappy old musicals as well. Every single poster in that season series we worked on he knocked out of the park. Beautiful stuff.

Surprisingly, he also was a Gilbert & Sullivan geek. When I called him up to work on an image for a Pirates of Penzance poster for the Seattle G&S Society, he responded by actually singing the first song from the play over the phone! I was sold immediately. He quickly sent me a concept drawing of a singing pirate via fax (remember those things?). It was a beautiful pencil sketch that the fax machine pixelated automatically so that after I photocopied the fax a few generations. the resulting dirty pencil stroke looked exactly like a real dirty pencil stroke–but was easily reproducible line art! I used that fax image gimmick as my 'photostat' for the poster! Over the years Mark and I designed around nine posters for the Gilbert & Sullivan society using that sketchy fax machine gimmick to produce the finished imagery. It was beautiful.

A jam cover for The Rocket from 1987 with art by Zingarelli, Peter Bagge and the late Michael Dougan. Art direction by Art Chantry. Image courtesy Jesse Reyes.

A jam cover for The Rocket from 1987 with art by Zingarelli, Peter Bagge and the late Michael Dougan. Art direction by Art Chantry. Image courtesy Jesse Reyes.I just remembered this cover of The Rocket that Mark worked on. It was our "summer fun" issue in 1987. At that point, Mark, Micheal Dougan and Peter Bagge used to regularly get together for backyard BBQs with friends and family. I'm not sure where the idea of using those BBQs as our "summer fun" cover image, but I immediately thought that might be a great place to do an exquisite corpse approach with these three dramatically different stylists.

I cut the cover into a "pie shape" and started with Mark. His intensely crosshatch style ended up setting the standard and the others followed suite in a way, trying to get their drawings to blend in with Mark's (which was not my "vision" for the project) but who's complaining?

Mark on the right, Pete on the left and Michael in the middle. "On the fence" are Denny Eichhorn and Cathy Croce. I'm not sure who exactly "drew" the masthead lettering (could have been any one of us, actually). Their drawings were inked line drawings in black and white. I added all the color with Rubylithe overlays and mixing process colors in some basic 20 percent builds (sounds hard, but actually pretty easy to do). Turned out beautiful.

Last time I saw Mark, I was speaking at the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh and he took me on a grand tour of the city and several of its amazing weird little eateries. In fact, I had the best fish sandwich I ever ate hanging out with Mark on that trip. If nothing else, that sandwich was a blessing from Mark. Thank you for everything, Dood.

Zingarelli with one his favorite things–a great sandwich. Courtesy Kate Alexander Zingarelli.

Zingarelli with one his favorite things–a great sandwich. Courtesy Kate Alexander Zingarelli.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·