Editor's note: Today we are pleased to provide an excerpt of Bob Levin's essay "See My Light Coming," about famed underground cartoonist Vaughn Bode, which was originally printed in The Comics Journal Special Edition Vol. 5 2005. This essay, as well as many other pieces Levin has written for the Journal appear in Levin's new book, Messiahs, Meshugganahs, Misanthropes & Mysteries, out this week from Fantagraphics.

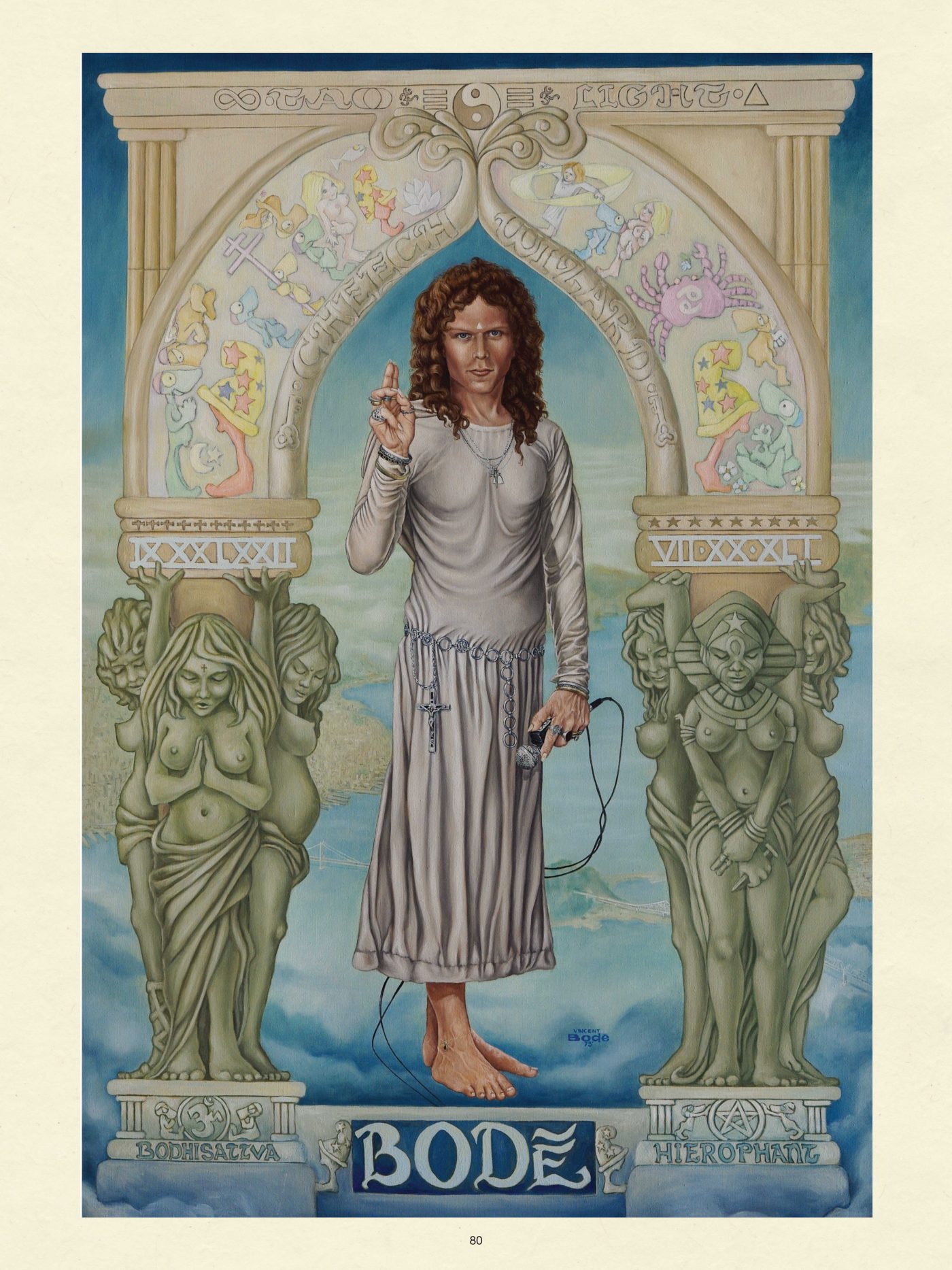

A 1973 portrait of Vaughn Bode painted by his brother, Vincent.

A 1973 portrait of Vaughn Bode painted by his brother, Vincent.At approximately 1:00 p.m., on Friday, July 18, 1975, the cartoonist Vaughn Bode came out of the bedroom of the apartment in San Francisco’s Mission District he shared with a lover who worked as a secretary at UC Medical Center, whom I will call Helene. He wore a monk’s robe and several necklaces. His light brown hair hung in curls to his shoulders. His blue eyes were lined and mascaraed. A white triangle was painted on his forehead.

“No phone calls today, Mark,” he said to his twelve-year-old son, visiting from New York. “I’m doing my God thing.”

“You look beautiful,” Mark said.

His father smiled.

“You see, Mark, I really am a high priest.”

He returned to his room. In the center, on the lid of a coffin, sat a Buddha, a Jesus, a Krishna, figures in the pantheon of a religion he was creating. Over the next few hours, to the accompaniment of Mozart, pausing only to slip $5 under the door for Mark to buy food, he worked through a series of steps as ritualized as a Japanese tea ceremony. He believed that each human sense was a window through which God communicated. This communication could be magnified by alternately silencing each sense. So he applied blindfold, ear plugs, gloves, apparatuses to mute taste and smell, each increasing his expectations and excitements as he approached a climactic extinguishing of his conscious self.

For this, he tied one end of a leather strap to a chinning bar braced on the doorway of his closet. He looped the strap around the bar several times and then wrapped it around his neck. He grasped the loose end of the strap in both hands and pulled downwards. He expected that, by cutting off of his air supply, he would black out and fall onto pillows he had lain across the floor. The strap would loosen, and he would regain his breath. But while unconscious, he would have been launched into a circumnavigation of the universe. He would have been in touch with worlds and visions he had pursued for most of his life. He would have melded into “everything.” He would have accessed Mysteries of the Light. When he awoke, he would have a harvest by which to enrich his art.

After he had performed this act for the first time, he had wept because he wanted so badly to return to the state it had yielded. Each of the five times he had done it since, he had gone further and gotten higher. He was four days short of turning thirty-four. Since Christ had died at thirty-three, he had told himself that when he passed that age, he would not cast this dye with God again.

He was at his professional peak. His work appeared in publications that ranged from the narrowest corners of the underground to magazines of worldwide distribution. Film production companies courted him. He had been only the third American to win the Yellow Kid Award from the International Congress of Cartoonists and Animators. His public appearances drew thousands. He had an agent at William Morris.

A necklace caught in his strap, and it did not release.

***

He had been born July 22, 1941, in Syracuse, New York. He had an older brother, Victor, a younger brother, Vincent, and a younger sister, Valerie. Their father, Kenneth, who was handsome, bright and unable to hold a job, was an unpublished poet and a drunk. Their mother, Elsie, was good-hearted, likable, and warm. She worked the assembly line at a GE plant in Utica. Because she worked and Kenneth was usually drunk, the kids ran wild. They were in and out of school, in and out of juvenile hall.

When he was sober, Kenneth would do anything for his children. But when he was drunk, he grew sad; and when he grew sad, he became mean. He beat Elsie; he beat the kids. He beat them while they slept, through their blankets, with a belt. To escape, they would sleep on the floor beneath their beds. When Elsie had been beaten enough, she filed for divorce. Vaughn was eleven, maybe ten.

Kenneth moved to Philadelphia. Valerie was sent to live with grandparents. Victor was placed in a children’s home and Vincent and Vaughn with different uncles in Washington, D.C.

The aunt and uncle who took Vaughn had a daughter his age. They were sure he would be her ruination.

“That Vaughn is no good,” they said in front of him.

“That Vaughn will never be any good.”

“That Vaughn will rape our daughter.”

It did not help his standing when they caught him in the basement masturbating amidst discarded automobile tires.

Nor had it helped that, when he was little, Elsie, who had wanted a daughter, allowed his hair to grow in ringlets and clothed him in dresses so that he resembled Shirley Temple.

Nor had it helped when his father mocked him because he was no fighter.

Nor when his mother forbade him to play with other children because they might do harm. There were times he did not know who the fuck he was, or what the fuck he was supposed to be doing.

Victor fled the home in which he had been placed and joined his father. From Philadelphia, he wrote letters to the rest of the family urging them to reunite the children. Finally, Elsie took custody and moved them to Utica, an aging industrial town of about 75,000 — Poles, Italians, Jews. Little Chicago, they called it.

A family offers models upon which to build a life. And it unleashes scalp-hunting savages against which to erect a fortress.

The Bode family contained strong contingents of Baptists, Catholics and Methodists. For a time, Jehovah’s Witnesses met regularly at their home. Vaughn saw that religion could bring meaning to empty lives, solace to aching hearts, courage to fearful souls. But no religion he met comforted him. At fourteen, he began to re-write the Bible — to tuck and taper its steamy blanket — to chip and chisel from its unwieldy weight.

At another point, he considered becoming a Jesuit priest. It was not, he later realized, the theology that had attracted him so much as the life of quiet contemplation, the channeling of sexual energy into the courting of God — the opportunity to wear a dress.

Then there was art.

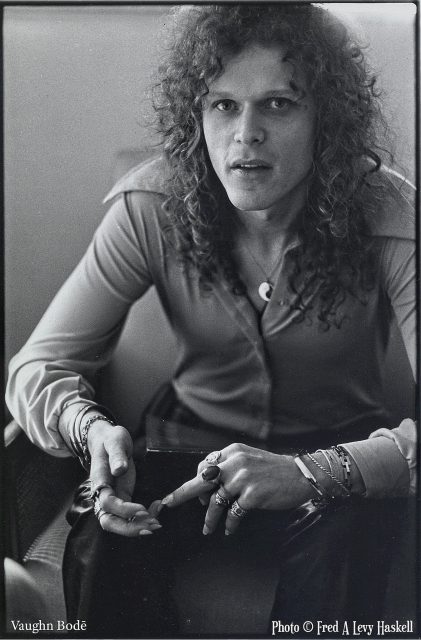

Photo of Vaughn Bode taken in 1975 by Fred A Levy Haskell.

Photo of Vaughn Bode taken in 1975 by Fred A Levy Haskell.He had drawn his first cartoon when he was five, his first comic when he was seven. No one else who came to supper or through a front door he was likely to step did that. This individualization strengthened his sense of a life apart. To the extent the drawing satisfied, the correctness of this course felt confirmed. Drawing drew him from where he was otherwise condemned to be. Its pencil lines and colors transformed his self as well as any other blank page.

He clipped his favorites from the paper: “Prince Valiant”; “Alley Oop”; “Pogo”; “Li’l Abner”; anything by Disney. He created his own characters, dozens, hundreds, perhaps thousands. Hobos found sunken treasure. Garbage men went to the moon. Mars and Venus were nearer than the corner store. He schemed out solar systems, populated alternate civilizations, every one more satisfying than the one to which he each morning awoke. He visited his worlds daily. The stretches during which he lingered lengthened. They were the only places that made sense or which he controlled.

At 13, he had his first “publication,” Samson bringing down the walls of the temple, on a church flyer. He plotted a career as a newspaper cartoonist. He intuited the need for a “front strip” the public would accept. It was not prepared for the worlds of his dreams. His first effort featured a man who resided in a trash can. Hobos. Garbage men. Trash can residencies. Smashed temples. His pages did not advertise a happy child.

If he had to be here, he thought, he must have a purpose. If he had a purpose, it must involve this talent that set him apart. And if his being apart exposed him to privileged visitations, he had a duty to lead others to places they could not find on their own.

At 16, at the kitchen table, he doodled two pipe-cleaner legs protruding from beneath a battered, extra large wizard’s hat. He cribbed his creation’s name, Cheech, from a nearby nut jar. A panel or two of combat left him shredded, lumpy, on his back. “What didcha’ expect, a dime store hero...?” he instructed. “Life ain’t at all lik dat, DOPE!”

***

Lenny Gotte met Vaughn in ninth grade — and became a lifelong friend. Gotte remembers him as quiet, calm, extremely creative, extremely ambitious, deeply involved with his cartooning. He was also interested in exploring, in thought and conversation, areas of the unknown. One of these areas, not revealed to many people, was sexual deviancy. “Nothing major,” Gotte says. “Closeted stuff. Not practicing anything. Just a lot of imagining and wondering ‘What-if...’ Trans-sexualism, S&M ... There was this book, The Seven Sins.”

One of the people who did not know of this interest was Barbara Hawkins, a shy, pretty, dark-haired girl, who resembled a teenage Sophia Loren. Barbara, who came from an abusive, strict, Baptist family, and who was a year younger than Vaughn, met him her freshman year of high school. They had classes together, which he passed by peeking at her test answers. She thought he was cute, funny — and, potentially, a “savior.” When she asked permission to go to a school dance with him, her father beat her. Her mother convinced him to relent, provided she was home by 11:00.

When Vaughn asked her out again, both parents said, “No.”

Vaughn’s cartooning was leading him nowhere. Barbara’s parents were thwarting his progress with her. Victor had dropped out of high school at seventeen, enlisted in the Marines, and already commanded a helicopter squadron. Well, Vaughn thought, Victor’s doing good. With Elsie’s consent, he quit school and joined the Army.

He served a year before going AWOL and receiving an honorable discharge, under medical conditions, on a psychiatric basis. Denny O’Neil, writing in High Times, a year after Vaughn’s death, says that he had blacked out several times from guilt feelings over homosexual acts. Mark says, “His commanding officer came onto him sexually and he freaked and ran into the woods.” Lenny Gotte says, “The service was just too harsh and violent for his personality.” Barbara says, “Vaughn simply was not a follower. He couldn’t take orders from anybody. He didn’t want to obey rules.”

He was back in Utica maybe a year, living with his mother, when he packed 15-pounds of his work into a portfolio and came to New York City, his hair brushed, his shoes shined, his tie knotted at his throat, determined to become “the hottest cartoonist in the Western World.” (Barbara had loaned him money for the trip. When her father found out, he hit her so hard he drew blood.) Vaughn visited newspaper strip syndicates and comic book publishers. He passed his rendered visions across the desks of balding, sweating, pot-bellied men who had room in their imaginations for boys of fire and invisible girls.

“Come back,” they said, “when you’ve learned to draw.”

He went home and burned several hundred drawings. He tried a Bible again but abandoned it after three chapters.

The first time he asked Barbara’s father for permission to marry her, he laughed in his face. “Like father, like son,” he told Vaughn. “Your father was a drunken bum, and so will you be.”

Barbara was still dominated by — and terrified of — her family. The only way she could be married, she knew, was at their church. So Vaughn started meeting her there, showing interest in the congregants, the service, the minister whose permission was necessary for any union. One Sunday, when the minister summoned the saved forward, Vaughn was among them.

“Are you certain?” the minister said.

“God has spoken to me.”

The minister had shaken the other people’s hands. He only glared at Vaughn.

The wedding, November 4, 1961, was attended by relatives and a few friends. Vaughn and Barbara found their own apartment. He went to work as a commercial artist for International Harvester but quit after a year. He and Barbara set off for California on a Vespa which he crashed in West Virginia. The rest of their savings went for train fare. After a brief stay with an uncle of Vaughn’s in Santa Barbara, they rented an apartment in Hollywood. Vaughn took a commercial art job, which he hated more than International Harvester, and at which he did not last as long. They returned to Utica and moved into a trailer — a small one.

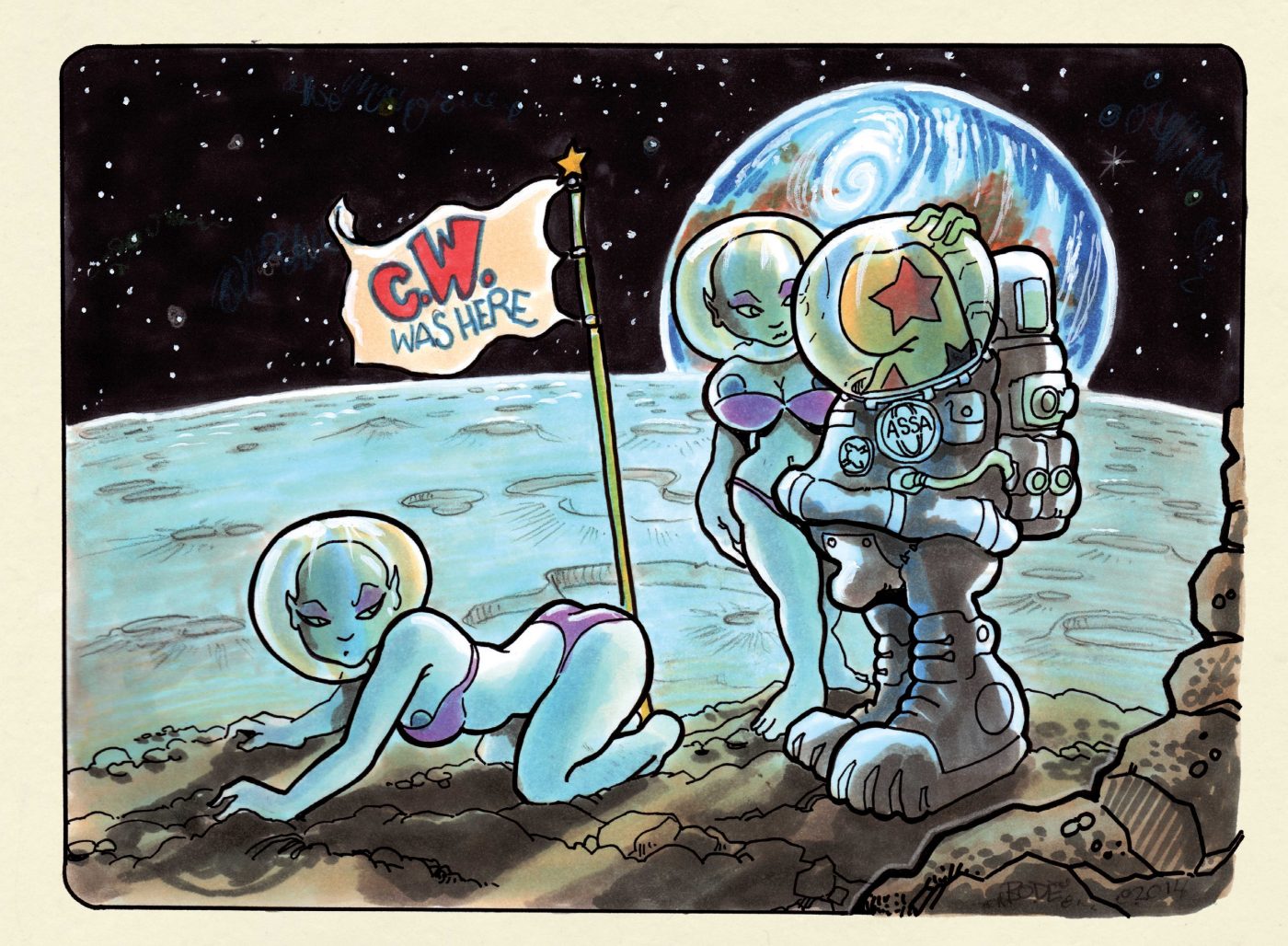

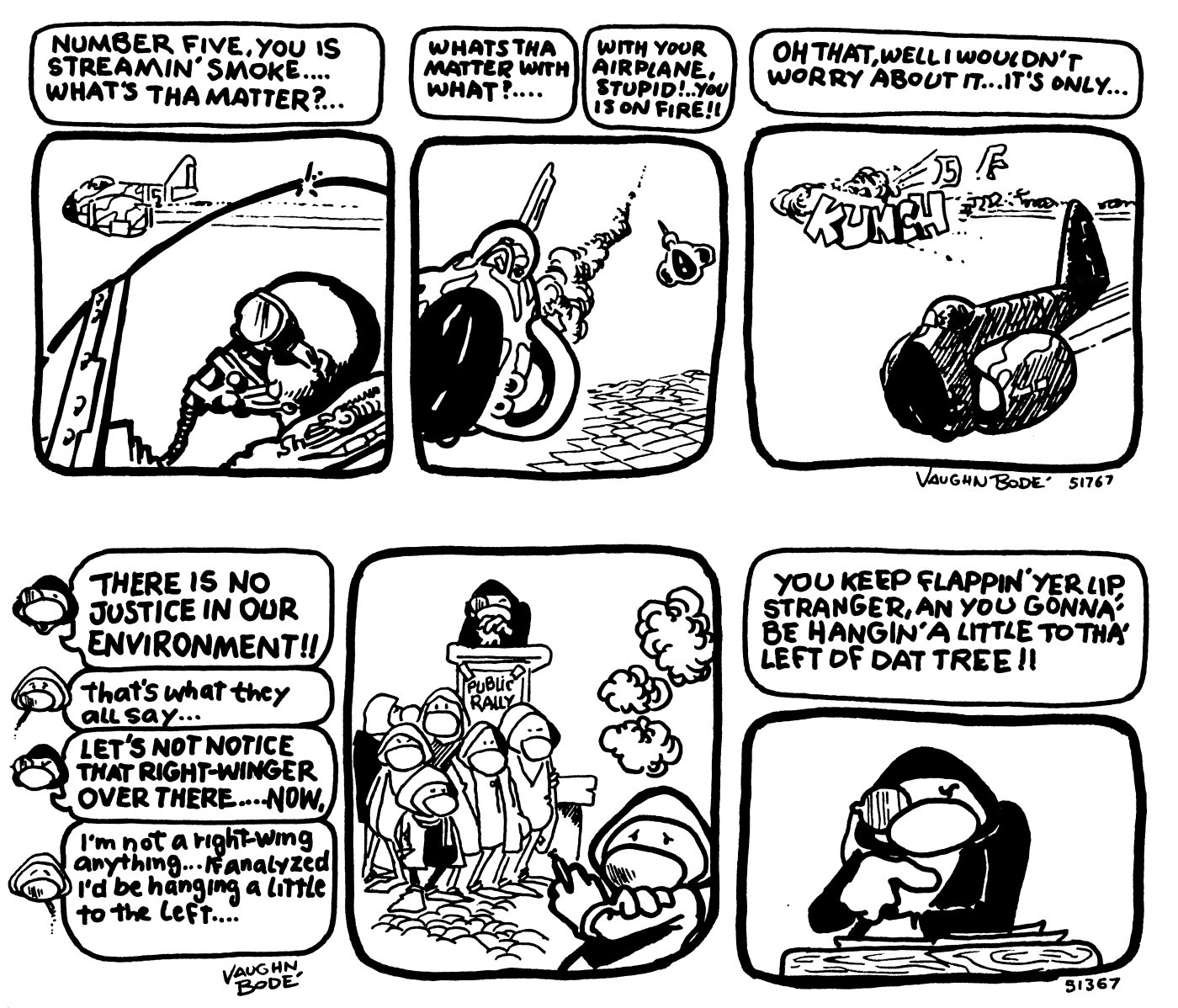

Image from Cheech Wizard's Big Book of Me.

Image from Cheech Wizard's Big Book of Me.***

“Nothing means nothing and Life is certainly an analogy to the Null,” Vaughn wrote in his diary the first day of 1963.1 He and Barbara, seven-and-one-half-months pregnant, were on welfare, living in a $20-a-month apartment. (Vaughn was pleased when she gave birth to Mark, since a son avoided the problem of “having a female as our next Messiah.”) He had been turned down by Utica College. He had unsuccessfully sought work at funeral parlors, state hospitals and as a stock boy. When he was hired as assistant manager of a downtown bookstore, he was paid only $1.15-an-hour and fired after eight months. More periods of unemployment and a short, unsatisfying stint at a commercial art studio followed. For additional income, he pawned his watch and Barbara’s razor. (He had already pawned their wedding set, her engagement ring, and wedding band.) His greatest success was an application to the VA for a service-connected, $46-a-month, psychiatric disability.

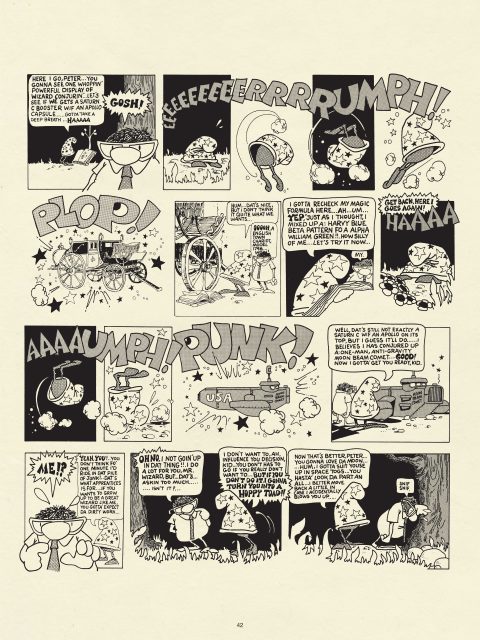

From Cheech Wizard's Big Book of Me.

From Cheech Wizard's Big Book of Me.The New Frontier had America floating on a rising tide of hope and vigor. But Vaughn lived like someone in a backwater shack. Reading his diaries for these years for clues of how he would burst forth is like staring at a sparrow’s egg and trying to forecast a phoenix. He bowled. He built model planes. He believed The Nutty Professor “delightful” and Gunfight at the OK Corral “really fine.” He compulsively bought — or shoplifted — books at the Salvation Army: a 1909 Webster’s Dictionary; a 13-volume history set; old National Geographics. He considered night school, a career in nursing, and — craving “some conformist movement” — the Air Force Reserve. He took long walks through the cemeteries of his rusting city and unappreciative culture. “The wind is howling madly...,” he wrote. “(I) walk in it for hours and think of Death.” He wondered if it held “beauty in its timeless voids.” He could not tolerate that it might not. “Nothing means anything if only blackness awaits.” He was wracked by unspecified “unbearable truths” – conflicts between “what my body wants, what my mind wants, and what everybody else wants.”

He sought relief through new sensations. He enrolled in a school for commercial pilots and logged flight hours. He joined a club which taught its members to make parachute jumps. In the clouds, he felt closest to his imaginary worlds. Each time he jumped, he considered not pulling the cord. Each time he waited longer.

But he always pulled it.

His dreams of artistic glory continued. Taking stock, he noted his “mechanical craftsmanship,” “rich writing ability” and “millitary (sic) trend,” as well as an inability to blend these into a commercial form. The strip he submitted to the Utica College newspaper was not run. The gags he sent to Dude, Gent and 1,000 Jokes were rejected. The queries he directed to art schools and agents, strip syndicates and comic publishers led nowhere. He displayed 49 drawings in a local art show, sold one, and won a blue ribbon in a category with no other entries. Jealous of the success of Charles Schulz’s saccharine Happiness is a Warm Puppy, he turned out his own, acerbic Das Kamph Is..., a hundred pages of captioned illustrations, such as “War is making a parachute jump behind enemy lines and forgetting your gun.” With money borrowed from his brother Vincent, he reproduced 100 copies in book form; but sales were minimal. In another creative burst, in one night, he produced 17 pages about a caveman he called Man. “I like the stupid little fellow,” he wrote, “but I imagine no one else would.”

He was, for long stretches, too nervous, depressed or beset by headaches to work. He was torn between his aspirations and his reality. “Am I good or am I bad or am I great? The latter must be true, or I wouldn’t have existed.” He believed he had been granted his talent in order to delight and instruct others. His inability to deliver was driving him mad. He feared he might never bring into existence his

21 creatures and their worlds. In his worst moments, he could write, “I can hate no one with more vengeance and discust (sic) than which I hold for myself.”

During the summer of 1964, America began to crack apart. The Gulf of Tonkin allowed Lyndon Johnson to plunge Vietnam into her belly like a sword. The murders of Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman confirmed that her racial fissures would not be bridged by singing “We Shall Overcome.”

In August Vaughn applied for admission to Syracuse University’s School of Fine Arts. Bathed in cold sweat, he hitchhiked from Utica to be tested, interviewed and to have his portfolio reviewed. “God of Gods,” he prayed, “be merciful.” When his acceptance came, he was overcome. “A whole new world is opening up for us. ... If only I can be worthy of this honor.” He was 23 — two years older than the seniors. He had his father’s beatings, his mother’s coddling, his army breakdown, his professional failures, the responsibilities of a wife and child on his back.

He also brought a destiny to seize.

“Bodē’s Consciousness” was first published in Vaughn Bodē’s Index, edited by George Beahm, 1976. Illustrations from “Bodē’s Underground Cartoon Concert,” promotional materials, Batam Lecture Bureau, 1973 and Bodē’s sketchook.

“Bodē’s Consciousness” was first published in Vaughn Bodē’s Index, edited by George Beahm, 1976. Illustrations from “Bodē’s Underground Cartoon Concert,” promotional materials, Batam Lecture Bureau, 1973 and Bodē’s sketchook.***

He found a $12-a-week room. He ate peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. He studied Light and Figure Drawing and planned to become an illustrator. And he sought ways to make himself known. He would give Syracuse something to think about besides Larry Csonka and Dave Bing.

The school paper, The Daily Orange, rejected his submissions; but, in December, Sword of Damocles, an off-campus humor magazine, accepted a six-page story, “The Masked Lizard.” Its protagonist, a four-foot-tall extraterrestrial, lives in the sewers beneath the university and subsists on nicotine and alcohol. He is also a CIA operative, who is shot multiple times, has a dozen grenades explode in his mouth, and is buried alive. But — death not being an end — is left singing in his coffin. The Sword sold out its 2800-copy print-run, but Vaughn was not impressed. “Wonder if I will ever be what I want. Seems hardly likely that I will shake the foundation of my rotten society. I suppose it will be enough if I shake the foundation of my own social sphere.”

For the next two-and-a-half-years, his work rocked the campus. The Orange ran a half-dozen strips. The art students’ magazine, Vintage, ran cartoons and stories. The Office of Student Publications published three cartoon books. The campus welcomed Vaughn’s bickering beatniks, warrior lizards, plots to blow up the Vatican. It embraced Rudolf, a bearded fanatic, whose efforts to restore dignity to a dehumanized, conformist society result in his being machine gunned and incinerated. It hailed the arrival of a Cheech Wizard, who had evolved into a police defying, profanity spouting anti-hero. (Like O’Malley, the god-father in Crockett Johnson’s comic strip “Barnaby,” his idea of a good way to demonstrate his powers is to perform card tricks.) Having been expelled from Sorcerers’ University (SU), Cheech spends his time at a local tavern. His world is full of ineffectual Communists, stupid ministers, evil rulers, and five-cent-a-hit assassins. At one episode’s end, those who see his face are rendered catatonic because they cannot “accept the truth.” But Vaughn’s greatest achievement may have been the “stupid, little fellow” he had created 16 months before.

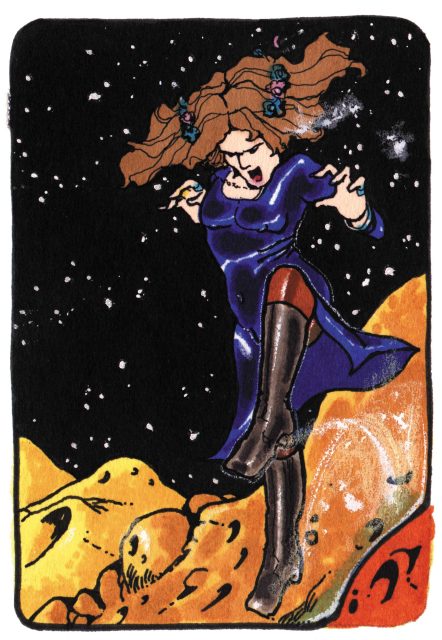

Bodē/Schizophrenia” reproduced in color from originals in Fantagraphics’ Schizophrenia, 2001. Originally published as Schizophrenia in B&W by Last Gasp, 1974.

Bodē/Schizophrenia” reproduced in color from originals in Fantagraphics’ Schizophrenia, 2001. Originally published as Schizophrenia in B&W by Last Gasp, 1974.“The Man” ran in the Orange, from October 1965 until February 1966, and was reprinted in book form the following year. Man led a simple life. He killed, and he ate. He had one friend, Stick, a spear, with whom he held one-sided conversations. When he found a second, Erk, a reptile, another caveman killed and ate it. (Man then killed him.) The loss of Erk left Man feeling like the wind, empty, cold and crying. But he can go no further in articulating or accounting for his feelings. He can neither bear nor transcend them. They teach nothing. They lead nowhere. He can only exclaim — and here the story ends — with Man atop a rocky crag, arms wide, mouth gaping, even Stick fallen into the void, “...I AM ALONE.”

“The Man”’s narrative distance was masterfully balanced in order to sustain a shifting, implicating moral complexity. Readers both identified with and were repulsed by this stunted being struggling to cope. They smiled, and they winced. Their grins spread, and their tears welled. He was all they had to hold onto; yet he was as if thorned. Vaughn had set before them a creature whose differences

were off-putting, but whose core humanity was magnetic. His anguish was one any of them — eyes opened, heart unshielded — had to share.

Larry Todd was already a published science fiction writer and illustrator when he entered Syracuse in 1966. Vaughn was, by then, at the heights of college cartooning, publishing widely, pissing people off. He was developing artistically through color experimentation, simulated 3-D technique, working on both a giant scale and through reduction glass; and he was manipulating the G.I. Bill to drop in

and out of school at will. (He would not graduate until June 1970.) “There was a tremendous energy boiling inside Vaughn,” Todd says. “But you could not tell in what direction it would go. It took a couple years for him to become seriously bent. Hell, it took a couple years for the idea of being seriously bent to even come up. At first, he just seemed another science fiction-Buck Rogers guy playing the game: ‘Anything you can think, I can think weirder. I can think anything weirder than you.’”

Vaughn, however, was putting some thoughts into practice. When Barbara and Mark had joined him, they rented an apartment in a large, sprawling, two-story house, before moving into married student housing. While he went to class and developed his art, she worked as a secretary, first for an insurance company, then a marketer of air conditioning. She enjoyed her new experiences and the people she met. But Vaughn was a celebrity, and his fame presented him with opportunities to explore areas previously confined to fantasy. One of these explorations involved having sex with Barbara’s best friend while she was in the next room. Another compelled him to describe to Barbara the sex he had with someone else. (He explained that these descriptions demonstrated how much he loved her.)

Then Vaughn began making requests. He wanted Barbara in 19th century lingerie. He wanted to use various “sex toys.” He wanted her blindfolded – gagged – bound. She liked the lingerie. She did not care for the tight leather garment with the hood. Once, after arousing her, he locked her in a trunk and left for another woman. When he returned, he kicked the trunk, off and on, so Barbara would know he hadn’t forgotten her. She was inside six hours.

“I took a while to convince, but I always did things for him,” she says. “I wanted regular sex, but I had never had sex, and he told me this was normal. And he balanced it by always having loving sex immediately afterwards. So I got what I wanted, and he got what he wanted. And we both enjoyed the second one. ”

Then he wanted to be worshiped during sex. She laughed at that.

A psychiatrist at the V.A. to whom Vaughn described his acts and fantasies said that if he did not stop, he would kill himself. But when you are young and coming into your powers, words like these have the effect of warnings that masturbation will drive you mad. And Vaughn had stronger fears.

The most disturbing thing Vaughn had ever read was The 50-Minute Hour, by Robert Lindner, M.D., which reported the psychoanalytic case study of “Kirk,” a nuclear physicist, who is “cured” of his insanity by having his inner, fantasy worlds permanently sealed off from him. Vaughn required his capacity to create his art in order to tolerate his life, but he could only create art by visiting his inner worlds and reproducing what he found there. And the only way his inner worlds could exist was if he nourished them with the adventures the outer world demanded of him. Later, Vaughn would introduce one of his works with a quote from Rimbaud

that, only by shattering the senses through exposure to “(a)ll forms of love, of suffering, of madness,” can a poet become a visionary. It does not matter if he is destroyed, for then others can stand upon him and see further.

The psychiatrist told Vaughn his contributions would enrich society — and prescribed Elavil. (Vaughn liked it because it left him feeling in control. Later, he would learn what things he wanted to control and what he didn’t.) The doctor also diagnosed him as a paranoid schizophrenic.

“(I am) Schizophraniac (sic)...,” Vaughn exulted, “full to the brim with fantasy worlds and ideas ... desiring to exist in another galaxy or another time.”

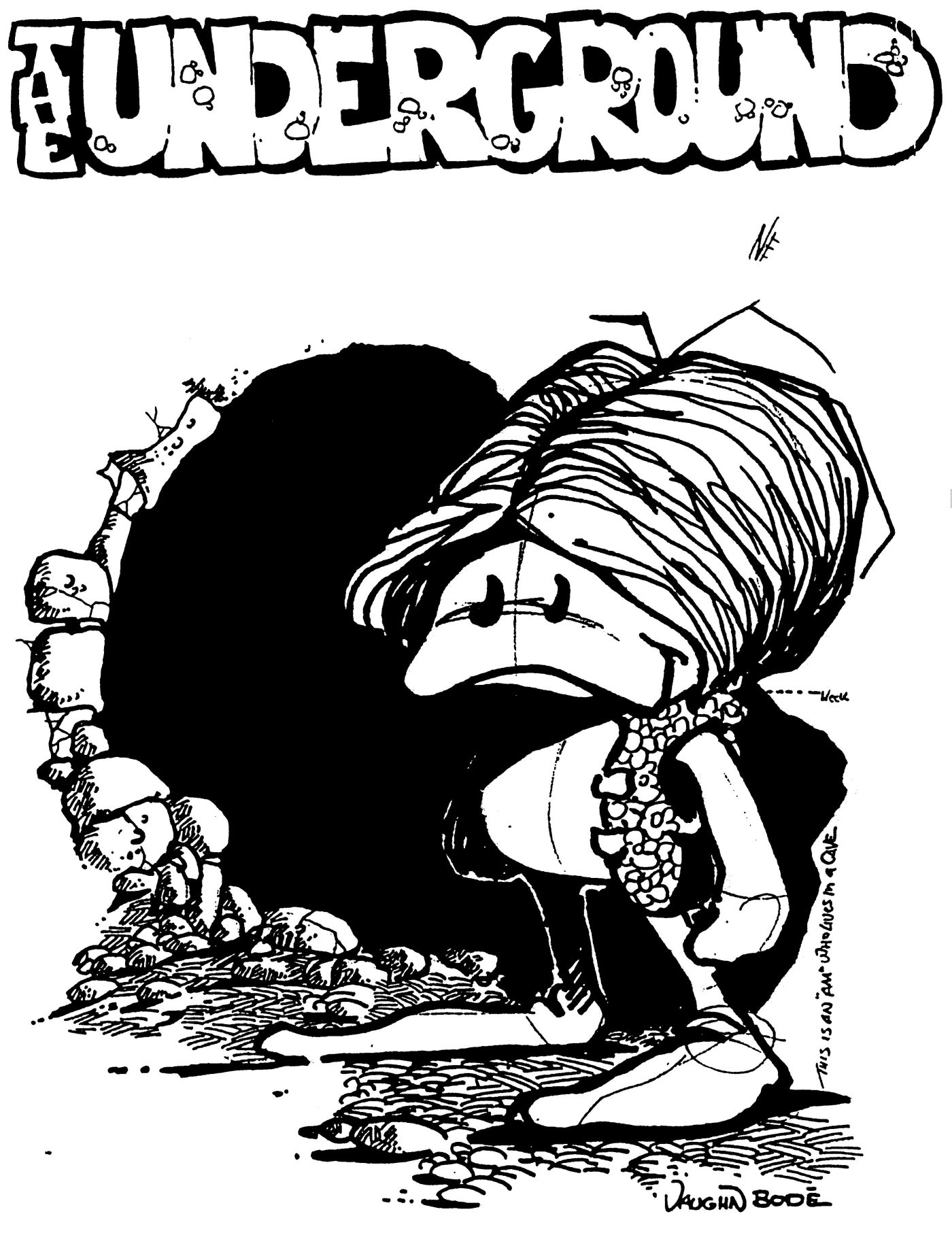

Cover drawing for Wayne Finch’s The Underground fanzine, 1969.

Cover drawing for Wayne Finch’s The Underground fanzine, 1969.***

The upheavals of the late 1960s had cast into being newspapers that printed cartoons sexually and politically unlike any before. In early 1968, Larry Todd showed one of these papers, The East Village Other, to Vaughn. It had work by Robert Crumb.

By this time, Vaughn had spread his work beyond Syracuse. He had been art director for a public relations firm, where he had created animated commercials, displays for trade shows, and a comic book, Powermowerman. He had contributed to dozens of comic and science fiction fanzines. (In two of these, Shangri L’Affaires and Witzend, he would post one of his most powerful narratives, “Cobalt 60.” It tells the story of another isolate, a hideous, homicidal mutant, who roams an Earth stripped and sterilized by nuclear war into dust and bones and empty winds. His contribution will be the slaying of the last woman capable of conception.) He had done promotional material for fan conventions and drawn covers and illustrated stories for the sci-fi magazines If and Galaxy. (After he won a Hugo in 1969, as Best Fan-Artist, Galaxy launched his cartoon serial “Sunpot.” But when editors, who objected to its sexuality, rewrote an episode without his consent, Vaughn killed his characters and was fired.)

Now he sent pages of original art to EVO. The staff regarded these strange lizard soldiers, who burned hooches and machine gunned children, and from whose mouths, when they died, butterflies spewed toward the sun, with awe and wonder — an attitude that did not insulate the pages from being left on desks and tables, while coffee stains upon them mounted. Finally, Trina Robbins, whose “Suzie Slumgoddess” the paper already ran, wrote to the artist. “Your stuff is amazing! Get down here!” No one she knew drew like that. All the underground cartoonist in New York influenced each other, and all of them were influenced by Crumb. But here were a unique conception and style. Here was an entire world, riven with horror and destruction, but rendered with a humanity and a compassion

that was heartbreaking.

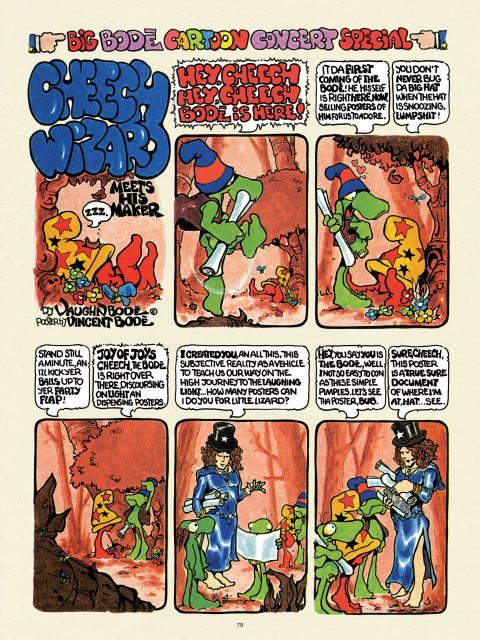

A Cheech Wizard strip, from Cheech Wizard's Book of Me.

A Cheech Wizard strip, from Cheech Wizard's Book of Me.Vaughn arrived, shaved, short-haired, and overwhelmed by the East Village. Robbins took him to lunch at a Polish restaurant, and all she could convince him to eat was an apple strudel. “He was so-o-o-o straight,” she says. “Then, of course, he ended up more weird than any of us.”

Vaughn had already published most of his EVO contributions at Syracuse; but he did plant several new, memorable images on its front page: a city erected atop a skull; a policeman shooting a newspaper; a terrified child huddling against the tomb stone of PEACE; Nixon offering help to “niggers”; a lizard desiring to “ball da entire womans (sic) liberation movement.” He also convinced EVO’s publisher to release Gothic Blimp Works, an all-cartoon tabloid. Vaughn envisioned it as a place for underground cartoonists to make their art known and earn money from it. He edited the first three issues, then resigned. Except for a few, scattered appearances, he was through with EVO too. Shepherding a flock of hippy cartoonists into the pastures of plenty required more than he could commit. And ideologues were calling for the UG press to toe lines he was driven to cross.

Many of the cartoonists with whom Vaughn worked — Trina, Kim Deitch, Spain Rodriguez— moved to San Francisco to join its freewheeling underground comix scene. But he stayed in the east, where professional prospects seemed greater. He continued to contribute to sci-fi mags and fanzines, drew for the Cryonics Society, did cartoon ads for Douglas Records (He saluted its offerings of Richie Havens, Lenny Bruce and Eric Dolphy as capable of causing “worms, diarhea (sic), chest phlegm, terminal halitosis, and five years in purgatory”), and turned out covers for the horror mags Eerie and Creepy. Two were collaborations with Larry Todd. One was with Jeffrey Catherine Jones, a New York City-based illustrator known for his sci-fi/sword-and-sorcery work.

Another new friend was Berni Wrightson. Wrightson had come from Baltimore, where he had drawn editorial cartoons, to New York, hoping to break into comic books with a style that combined Frank Frazetta and Graham “Ghastly” Ingels. He met Vaughn at a comic convention in 1969. (In 1971, when Vaughn was busy with other projects, Wrightson illustrated and lettered installments of his “Purple Pictography” series for Swank.) Wrightson recalls Vaughn as very collegiate then, still very much the straight arrow. “He had a wide range of philosophical and religious interests, but he was no zealot. He seemed to gather and assimilate information only in order to enrich his work. He was pre-occupied with landing the next job, with securing good accounts. He was very intense and very confident. He envisioned himself becoming the Walt Disney of underground comics.

“We used to joke about Vaughnbode-land with rides that ended in horrible deaths.”

Vaughn spent the bitterly cold winter of 1969 at the far end of Long Island with Barbara and Mark. He took the train into Manhattan to deliver his assignments. When he returned and reported what he had gathered and assimilated beside a paycheck, Barbara learned how open her marriage had become. “I wasn’t too happy about it. It was pretty heartbreaking really. I knew he loved me more than the other women, but it’s hard sharing a husband, to say the least.”

Vaughn had complaints too. Most of these women wanted to skip the restraints and lingerie and just get it on.

Vaughn had broken into the slicks with Cavalier in May 1969. A Playboy cousin, with chewed fingernails and stains on its raincoat, it may have lacked sophistication; but it had edge; and it paid better than the underground or fandom. For a while, it also had quality. It published Crumb, Art Spiegelman, Harlan Ellison. When Crumb quit contributing because of a negative article it had run on UG comics, Vaughn took his slot. The editors promised not to censor anything he submitted unless it could get somebody jailed. He produced four black-and-white or halftone strips per issue. They were six-to-nine panels long, in a form he named “Pictography,” which left the word balloons outside the panels and the art uncluttered. The series was entitled “Deadbone.” In April 1970, it switched to color.

Deadbone was a four-mile-high, volcanic mountain, populated by lizards, toads, and bare breasted, big hipped objects of sexual desire (and vessels for its easy fulfillment) that came to be called “Bode Broads.” Deadbone was “an evil and insane society,” created a billion years ago as a rehearsal by the “murky mysterious forces” which created our own. It was a blackly comic world of bashed heads and ripped out hearts, overseen by gods who studiously ignored or flippantly destroyed their worshipers. Death came from meteors and submarines, rifles accidentally discharged and monsters lurking around corners. Deadbone’s citizenry were pushed off cliffs and squashed by overly passionate robots. Since women were ridden like horses, they were shot if they hurt a leg. Others were bound during lovemaking, turned into “lumps of leather and rubber,” and buried alive. Among Deadbone’s populace were a lover of clouds who falls to his doom when he steps out on one; a preacher who murders children in order to speed their passage to heaven; and a mourner for a lost brother who, sitting alone, on a rocky crag, in a cold night wind, concludes, “...(L)ife is a good thing to be, even if we got to be dead tomorrow.” There was also a lizard who holds his breath underwater so long that he achieves an

expanded consciousness — “the “Grooviest thing I is ever done” — and drowns.

Sequence from Bode's "Cobalt 60" story that ran in Witzend #7.

Sequence from Bode's "Cobalt 60" story that ran in Witzend #7.Vaughn’s solution to the casual, inevitable destruction his work posited was absolute sexual indulgence. His cartoons rippled with celebratory references to cunnilingus and fellatio, masturbation and S&M. His call had a philosophical/theological basis. “(W)e don’t just ball each other,” he wrote. “We ball life.” Repressing sex causes us to obsess about it. These obsessions block our minds so that we can not receive God. Vaughn wanted to open everyone to this reception. Something must fill us besides what he knew otherwise to be there.

He also used his strip to address political issues. (His take on Kent State was a duel between reptiles, one armed with a brick and the other a machine gun) and to work over personal concerns (a troubled marriage; a father’s death.2 He achieved poignant episodes, like “River Meat,” in which a corpse wonders, “what I was before I got to be a bobbing, bloated, floating thing.... I might have walked on top of the actual ground and waded through autumn corn. I could have heard a different drum.” And he presented deconstructive riffs, startling in their originality. “Self,” for instance, plays within an artist’s mind, with characters investigating the stored memories which triggered their creation. In the next-to-last panel, they peer out through the eye that drew in the perceptions that begot them. Then the point of view reverses; the last panel, shot from the outside, reveals the full being in whose eye they stand: the author as a teary child, naked but for a strait-jacket, to whom electrode-like wires attach.

But ghosts shadowed Vaughn. They hung in the corners. They hid behind doors. Men and women acted towards one another only as sexual aggressors or exploiters. Friends only abused and debased. Where was the child on the knee, the wife hand-in-hand, the comforting touch, the reassuring word? The ecstatic license he projected entailed a remove from gentler social comforts that he could not will his art to span. He had been cast too far by a childhood he could not extract. It sparked his achievement; it would command his demise.

The post ‘See My Light Come Shining,’ an excerpt from Bob Levin’s <i>Messiahs, Meshugganahs, Misanthropes and Mysteries</i> appeared first on The Comics Journal.

![Ghost of Yōtei First Impressions [Spoiler Free]](https://attackongeek.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Ghost-of-Yotei.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·