“To allow kids to see themselves as a creator, not in the model of somebody else, but in what inspires them and what makes them want to be storytellers.”

Best-selling, award-winning comics creators Scott McCloud and Raina Telgemeier have combined forces this year to create a new graphic novel, The Cartoonists Club, which combines their past work in narrative nonfiction and instructional comics to provide kids with a primer to making comics—and to thinking about how to approach comics storytelling and their own creative process.

In this interview, which ranges from their early introductions to comics to their recent book tour, Telgemeier and McCloud talk to The Comics Journal about how this book came to be—and their hopes for it as an inspiration for the next generation of comics-making.

–Gina Gagliano

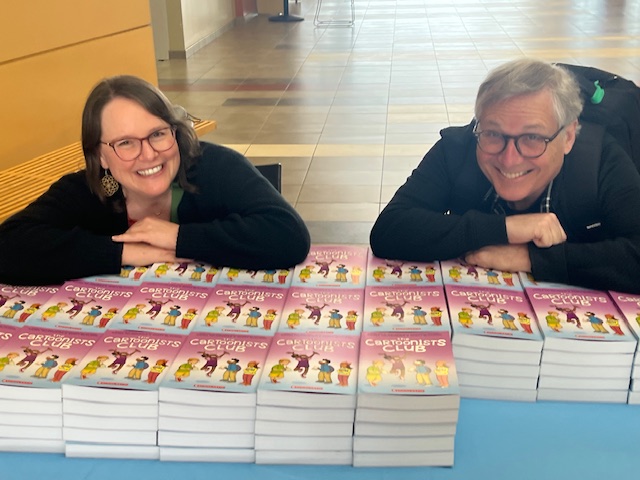

Raina Telgemeier and Scott McCloud

Raina Telgemeier and Scott McCloud

GINA GAGLIANO: When did you two first become aware of each other's work?

Raina Telgemeier

Raina TelgemeierRAINA TELGEMEIER: I’ll go first. Understanding Comics was published when I was sixteen. My dad was a comics fan, and kept abreast of what was going on in publishing. He read about it in Whole Earth Catalog, and he ordered a copy. After he was finished with it, he gave it to me to read. I was the other comics fan in the house—I was reading comic strips in the newspaper, drawing them for my own high school newspaper. I was making comics every single day, and my dad knew Understanding Comics would at least interest me. But it did more than that. It sparked my curiosity and my excitement about the medium, and I felt like, here was the nerdy book that I had been waiting for, with exactly the kinds of things I wanted to talk about. I loved it

SCOTT MCCLOUD: And props to your dad for also showing you Barefoot Gen around the same time; that’s quite a one two punch. Oh, the wonders of comics—and also: humanity is terrifying.

The first time that I became aware of your stuff was probably at the small press shows. Was it APE in San Francisco, your own backyard? And you were one of the fresh young faces just creating comics and embracing the positivity all around us in those days. I’m guessing 2004, but really, the whole early 2000s were characterized by that.

I saw you as part of a scene but, I don't think we quite understood the degree to which you were sui generis. You had something in you that became singular and very potent in triggering the next generation. But at the time you were just part of a very happy, supportive and enormous cohort of creators, many influenced by manga, a lot of you finding each other through the internet in the early days. And my whole family just fell in love with your comics, but we didn't yet know what you had up your sleeve. I also was running into your stuff through some of the online portals like Joey Manley's. Did Smile start on Girlamatic?

RT: Yes it did. It started on Girlamatic.

SM: And I didn't even get it at first. Gene Luen Yang was also serializing American Born Chinese. And all I saw was ‘oh, but it just looks like pages just put up on the internet.’ I didn't understand how important both comics would be later on, because I was still too hung up on the form.

RT: That’s interesting! I always knew that Smile was going to be a book. I didn't know if it would be a self-published zine or if it would be printed in twenty-four page floppy format, or if it would be picked up by one of the small press indie publishers that were also exhibiting at small press shows alongside me and my friends.

In the early aughts, it wasn't clear where things were headed for comics. I had my first conversations with Graphix in 2003-2004 and started working on The Baby-sitters Club for them, and at the same time I was putting Smile up on Girlamatic. BSC was my day job, and Smile was my project for fun on the side. I was having fun and just trusting that it was all going to make sense at some point.

SM: And it's a good example of editors mattering in the earliest stages, because you're one of those rare creators who actually had that ‘Lana discovered at Schwab's’ moment when David Saylor (the Creative Director of Graphix) saw the potential in what you were doing.

So we're in 2004, now we've moved on in years from the Whole Earth Catalog. Following that, when did you two meet each other?

RT: We had met once or twice at comic conventions and said hello, and it was always Scott and Ivy and the kids, and always a fun conversation. But then when Kazu Kibuishi first published the Flight anthology and gathered that group of people together, even those of us that were not in the first couple of volumes were often invited along to dinners and parties. I got to sit with Scott and family at Buca Di Beppo once during a San Diego Comic convention, and I feel like that probably sealed the deal.

SM: 2004 was the year that we had the famous 100-cartoonist dinner that Kazu organized. Raina had not yet appeared in Flight, but was going to shortly. And I very much thought of that as ‘the Flight generation.’

One of the reasons that I call 2004 a “summer of love” was because that was when the web was still a mostly positive influence on comics culture. Everyone was just showing up on LiveJournal; Twitter hadn’t begun yet; and they were showing up as themselves. Yes, there had been some flame wars—I was subject to one or two of them—but for the most part it was a very positive scene. And the social structure of comics communities was changing dramatically, too.

RT: There was a lot of cross-pollination between the web cartoonists and the indie and self-published cartoonists. We were basically just kids making stuff and making friends, finding our way. The industry as it exists today did not exist in 2004. People were starting to talk about things like e-publishing and e-readers and whether that was what webcomics were going to turn into. It was unclear, but we all had optimism. A lot of folks were making money by selling t-shirts, and they had fandoms and friend bases that were all gathering on forums and message boards, and yes, on LiveJournal, and in the comments sections of the Modern Tales websites. It was a nice time. We were all just finding our people, both in virtual spaces and then in real life spaces.

SM: And there were some vitally important tipping points. There was the tipping point of gender, for one thing. This was when it became virtually inevitable that women were going to be reaching parity with men and probably even eclipsing them—at least I was predicting it in those days.

And that began to flatten the social hierarchy. Instead of dudes jockeying to see who was on top, people were more focused on ‘am I on the outside or in the inside,’ and so not being a jerk was suddenly a priority. We also began stepping out of the zero-sum game mentality that had dominated until then. There was a growing awareness that markets could be created, that an individual coming into the community could be responsible for bringing an army of new readers, rather than simply cannibalizing the readers that were already there.

RT: I think that was reflected when Scott wrote Reinventing Comics. I remember reading it and feeling like my mind just been blown. The future felt so expansive, and comics could be anything you wanted them to be. I always felt like reading your work made me smarter, Scott!

SM: That's so sweet. Especially, of course, because I think of Reinventing as my troubled middle child.

RT: Then you made Making Comics, in 2006. You and your family were on your fifty state tour….

SM: Yes, yes, we were.

RT: I bumped into you a lot on that tour. You guys were all over the place! The Baby-sitters Club graphic novels started publishing in 2006. I was doing events for those, and Scholastic was partnering with bookstores and bringing me to this new kid audience. But it wasn't immediate. I was not an instant superstar.

I was still kind of climbing toward a goal I couldn’t exactly identify. I think it was just sustainability: ‘I would like to be a cartoonist, and I don't want to have to have a day job.’ By 2006, the BSC graphic novels were my full time gig, and that gave me the freedom to do more conventions and travel. I began to speak with audiences of librarians and booksellers. It was a lovely time.

Scott, I’m curious about when you were working on and then finishing up Making Comics, did that feel like you had sort of completed your narrative arc?

SM: I think that Making Comics in some ways was me trying to keep myself busy on something productive after my Waterloo, trying and failing to reinvent the world economy and reinvent the shape of comics. Neither was going very well. Most web comics stuff wasn’t nearly as creative as I had hoped it would be, and the business stuff was already starting to scramble and sour a little bit. But the community online was fantastic. So I just thought, okay, all right. If I keep hitting my head against this wall, I'll go crazy. Let me do something that I know is productive, putting out some ideas for just how to make better comics.

But in other ways, comics was expanding as I always wanted it to. All of the stuff I talked about in the first half of Reinventing Comics—all the ways that comics could be better—that was actually happening. The digital stuff was not happening the way I wanted it to, but.the other stuff was. Sitting out there on the Sails Pavilion at SDCC, it was like the whole of comics was a giant sail and the wind was pushing it forward. But I tried to focus my attention where my attention would have a multiplier effect, instead of just becoming obsessed with my little hobby horses. Because I've seen other cartoonists do that and it didn't go well.

So you've all built the comics industry, and then having done that you were like, 'let's do a book together' How did that happen?

RT: Fast forward twenty years.

SM: Oh, God. Was it that long? Yeah well, it was.

RT: No, it's fifteen years. Or nineteen!

Lynda’s finished quanto comic

Lynda’s finished quanto comicIf you're saying you met in 2004 and now it's now it's 2025, twenty years later, you're reaping the rewards of all the community building, and work, and foresightfulness.

RT: One of the things that I have seen through my career is that as more kids are coming to comics, and many more graphic novels for kids being published, these kids want answers to their questions. Those questions are, ‘how did you do it? What gave you the inspiration to do it? How come it's so hard? Why does it take so long? What are your number one tips?’ I have an FAQ section on my website with all the questions that the kids ask over and over again. And in every single audience there’s that one kid, the nerdy one, the creative one, the one with the sketchbook full of ideas that goes, ‘So what advice do you have for somebody who wants to be a cartoonist?’

I have written essays, I have done lectures, I have done workshops. I felt like I had tried to be in so many places at once to answer that question, but there's no way for me to have a one-on-one conversation with every single kid that asks…unless I were to make a book about it. And I didn't want to do that!

I thought, ‘well, somebody else should make that book.’ And there are other books that have been published that are along that line, tips and tricks, ideas for how to write stories, how to draw panels, how to create characters. But I felt like what my readers were looking for was something very specific.

And I thought, if I could wave my magic wand, I’d conjure a book like Understanding Comics, but aimed at an eight-year-old kid. I kept hoping someone would make that book, like maybe Scott would create a young readers’ version of Understanding Comics. Or maybe Gene Luen Yang would write a book about how to make comics (he’d be so good at it!). And years continued to pass by, and kids continued to ask me the same questions.

Finally, I just marched up to Scott at a party. This was in 2019, we were at the Graphix party at San Diego Comic-Con. I was like, ‘Scott, just going to throw this out there: what do you think would happen if we combined Smile with Understanding Comics?’ And this was Scott's response:

SM: Well, as usual, I didn't instantly get how important this could be, but my family did because they were there with me. And as usual, Ivy and the kids, they basically told me, ‘you're doing this.’

And I very quickly saw the wisdom of it. And, yeah, it was a slam dunk. It was so obvious that this book needed to exist. That’s something that you want when you're embarking on a new project. When there's this whistling in your ear from the sound of the air rushing in to fill this hole in the universe where this thing should exist. It definitely had that feeling right away. It took us five whole years to do it. But it had that really satisfying feeling of a thing that should exist.

And meanwhile, you can't make a million new readers as Raina has without accidentally making at least a thousand new artists along the way. We had to be ready for them.

RT: I also thought about what nine-year-old Raina would have wanted. She wanted a master class. She wanted a teacher. She wanted a guide. Someone to sit with her, not to show her how to draw boxes and word balloons, but how to think about what goes inside of them, what happens between them, why they're interesting, the kinds of stories that you can tell with them. I figured it all out slowly and on my own, through a lot of trial and error, and that's a fantastic way to go about something. But it's also lovely to have a supplemental piece of work that you can refer to and that you can turn back to. People talk a lot about How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way, as being a foundational text.

SM: It's actually a good book.

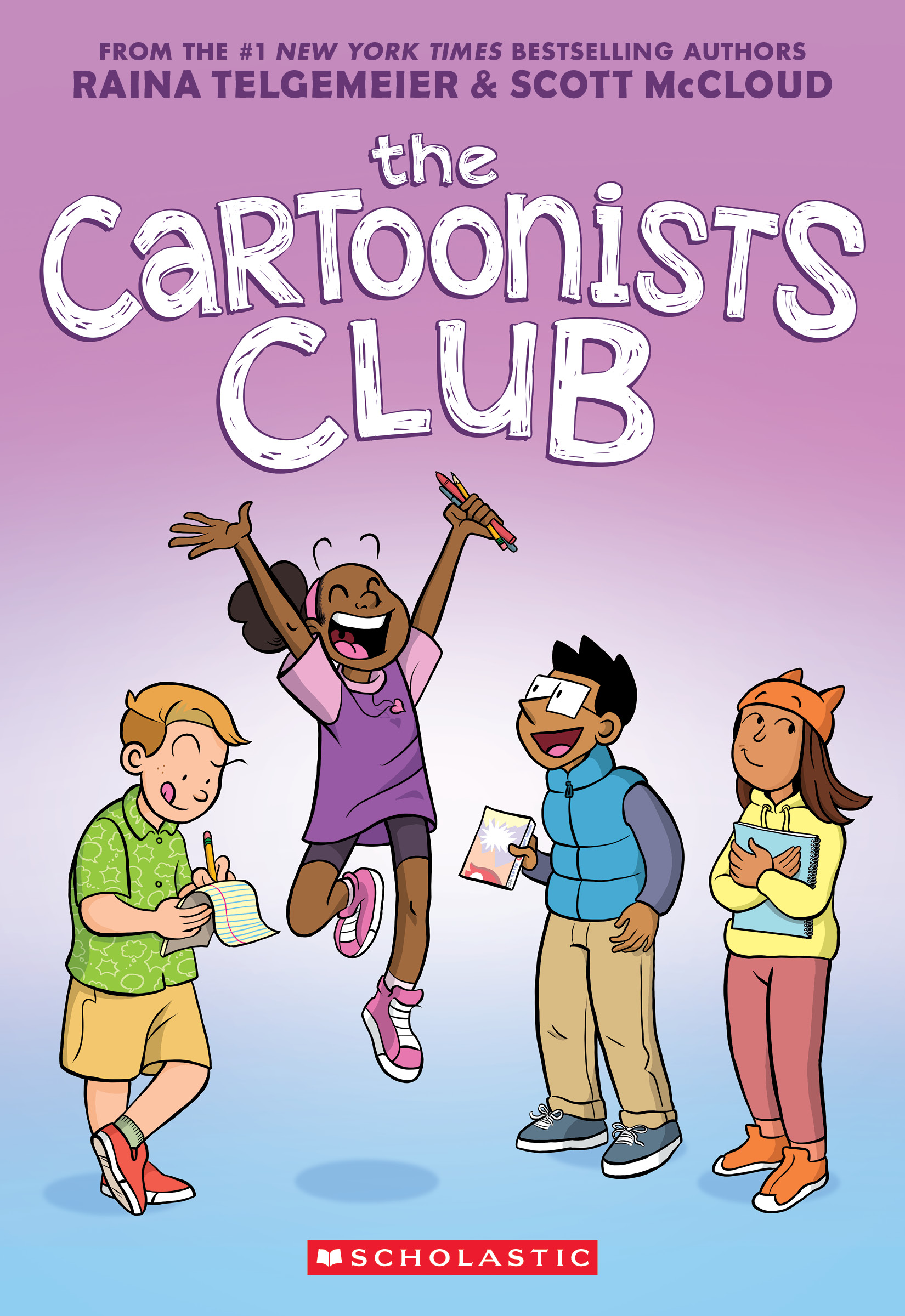

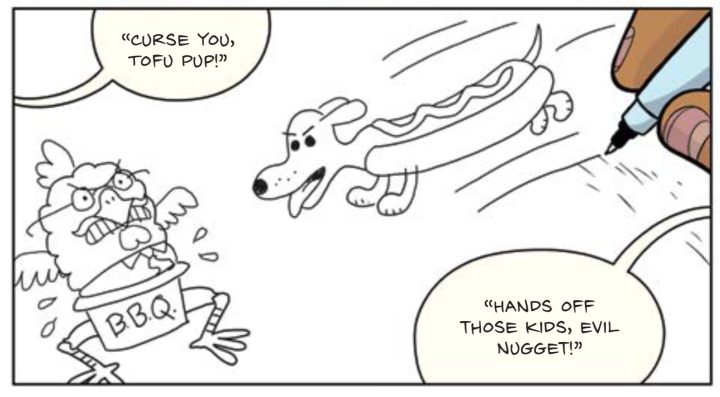

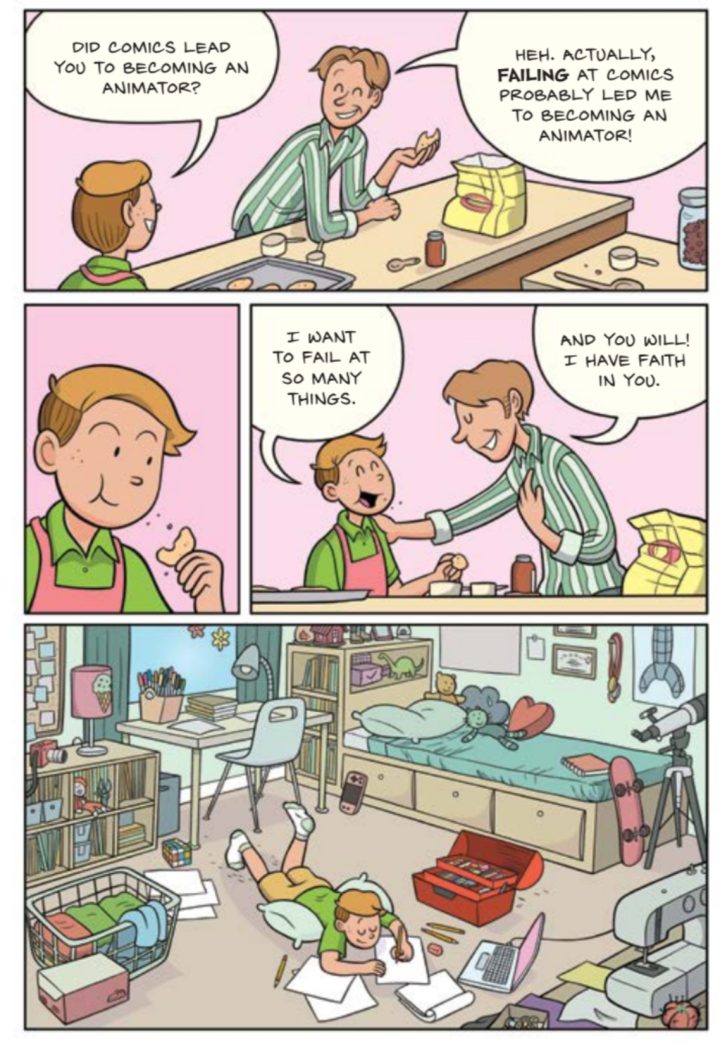

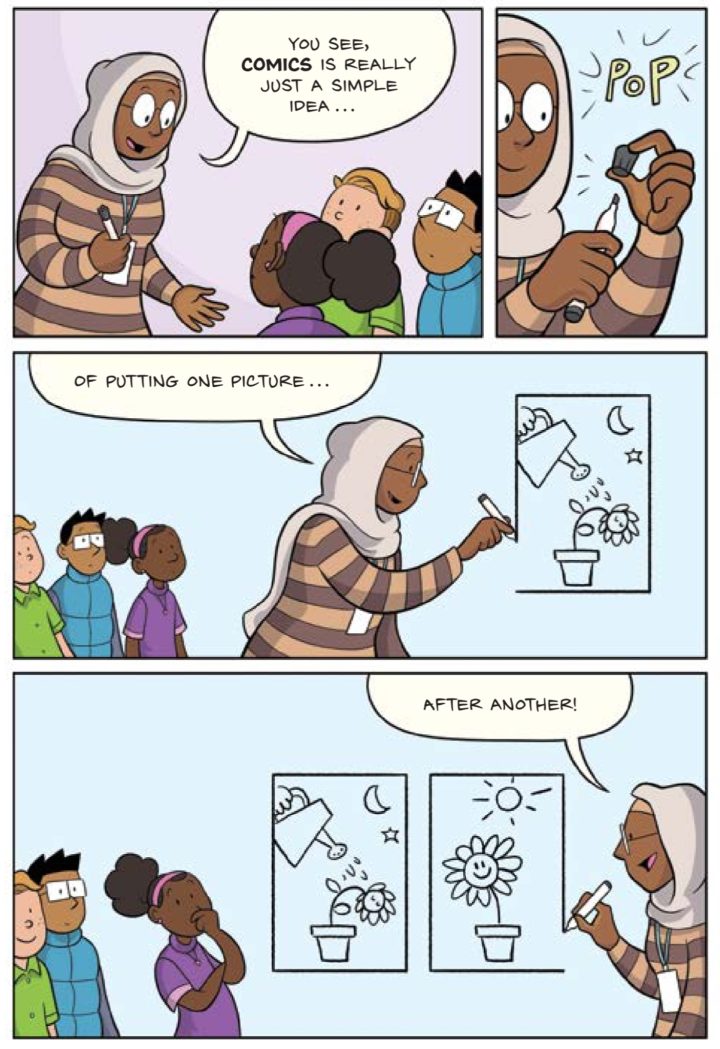

The Cartoonists Club by Raina Telgemeier and Scott McCloud (Scholastic, 2025)

The Cartoonists Club by Raina Telgemeier and Scott McCloud (Scholastic, 2025)RT: Yeah, but I never wanted to draw comics the Marvel way. I wanted to draw them the Raina way. And I think that's part of what we were aiming for with The Cartoonists Club, to allow kids to see themselves as a creator, not in the model of somebody else, but in what inspires them and what makes them want to be storytellers.

SM: Kids start off searching for tips and tricks on how to draw comics, but they're also looking for a philosophy of why to draw comics. And some kids are embarking on that journey alone. Not all of them have friends who are making art as I did. And one of the cool things that happened was as the book evolved, it became much more about the kids finding their own way rather than having wisdom fed to them like baby birds in a nest.

So this is the next step in your comics cultural domination plan.

RT: Yes! Haha.

SM: It's coming together haphazardly.

First getting people to read comics, then getting them all to make comics. So those 1,000 people will create a million more comics readers each.

RT: I like the math.

SM: I do too, yes.

What was it like working together? What was your process – how did you go from being at that Scholastic San Diego Comic-Con party to actually getting work down on paper?

SM: Well, it's important to keep in mind that we both write and we both draw, and that's how we approached the collaboration, too. We both do rough versions of the comic in the earliest stages. So, we talk about story and make notes, but when the work really begins, we start doing doodle drawings of the characters with word balloons right in the panel. And that's how the script is worked out. Raina would do a few pages, I would do a few pages. We'd toss them back and forth. We'd suggest revisions to each other. It was very much a collaboration of both art and story, because we both like to be able to read our comics before we draw them. So we did an entire draft that way of back and forth and back and forth and back and forth.

RT: All as thumbnails.

SM: Yep, just as thumbnails.

So this seems super intense because okay, looking at the book which I have here, you have the bit at the end which is ‘how we made this’ and you have the part where it's like, we have a page and Raina drew panel one and four and Scott drew panel two, three, and five. How did this work? Do you have a collaborative document that you both had access to that you were simultaneously drawing in? Were you passing things back to each other one panel at a time?

SM: Well, that rough page in the back of the book was from the third draft, when it had gotten mixed up even more. That’s why it seems almost as if I draw a panel, Raina draws a panel, and so forth. But actually, what would happen is Raina would do maybe nine or twelve pages, and I would come back with a bunch of others. But it's when we started to revise and make changes and adjust each other’s work that you started to see those things where our panels were right next to each other, where they were cheek to jowl. That's because we were constantly making changes to it, suggesting changes.

RT: There was a lot of Photoshop.

SM: Yeah, a lot of cut and paste. Raina's much more organic, like ‘I'm just going to draw this on a piece of paper and scan it.’ I had my draft on a elaborate series of little shelves in Photoshop so that I could keep track of everything. So it looked very different on my screen than it looked on Raina's screen. But, basically it was the same process. Like a story conference at a company like Pixar, where you're just looking at the storyboards on the wall, and they're just looking at what's already been done and saying, ‘hey, wait a minute. On panel two, what if it was like this?’ And they actually go up and they draw a new version.

RT: It was the digital equivalent of sitting in a conference room together and sticking Post-it notes over each other's pages and saying, ‘wait, wait, let me redraw that one facial expression. Or I think I could make this line of dialogue better here.’ I admit, it was a little intimidating to overwrite the great Scott McCloud!

SM: [laughter]

RT: I feel like he needs a t-shirt that says, ‘genius at work.’

SM: It was intimidating for both of us because I was on Raina's home turf. So whenever our styles differed, I knew in the back of my head that one of us had the track record. I had to learn to loosen up and go with the flow so that when we were talking about more general ideas that I had to be more general too. I had to allow my characters and my drawings to be more about the general tone, because it was that looseness that allowed it to be more organic in the long run.

RT: We have different approaches to writing and storytelling, but the technical way that we do things is the same.

SM: Yeah.

RT: We both thumbnail, we both plan a little bit and then just jump into thumbnails. And I don't really have a plan when I'm doing that, and I think Scott does. But because we were kind of going off to tackle one chapter apiece, and then we would compare and then stitch them together, in the end we wound up with something that felt like a true combination of both of our voices. We went through three drafts of editing the story, it went through a lot of changes. But I think the end product is kind of like the third head in our two-headed-monster. The amalgamation of Raina and Scott.

SM: And the most encouraging thing, the brass ring for me, was when we got to the end and David Saylor, who had been part of the editorial process along with our editor, Cassandra Pelham Fulton, David said that he had read the finished version five or six times at that point. And he said it felt “seamless” to him, and I think both of us took a bit of a mental victory lap when we heard that.

That's great. I want to talk a little bit more about this process and the other people that you worked with. I want to talk about editors, but I also want to talk about the other art people who helped you out. Looking at the book’s credits, it looks like you worked with Ray Baehr on inks and Beniam C. Hollman on colors. And then Jesse Post on letters. So how did that go? How did finding those people and working with them, how did that all come together?

RT: Ray is an old friend from my New York days. We both went to SVA. We were both in the mini-comics scene for a long time, and I reconnected with them at Comics Camp in Juneau, Alaska a few years ago. I knew I wanted to work with an inker on this project, which would save me at least six months of time, and my drawing hand would thank me. And since Scott and I were doing so much cross collaboration, I figured Ray might end up inking some of what Scott was drawing as well—Scott, did that happen? I don't actually remember.

SM: I worked with Ray in a couple of spots, but for the most part, I inked all my art. We should actually go back just a little bit and explain the breakdown.

RT: Yes! I knew I was going to be drawing the settings and characters. And I knew that Scott was going to be adding the art that the kids drew. We thumbnailed out the basic shape of Scott’s art together. Moving from thumbnails to finals, I supplied all the pencils for characters and settings, and then Ray inked what I drew. Then we sent those files with the big blank spaces over to Scott.

SM: Yep, and I just basically I drew what the kids drew, so I had to impersonate four different middle schoolers and their art styles, along with the somewhat diagrammatic, explainable art of Ms. Fatima, their librarian and media specialist, and occasional other oddball floating objects. But all of the real world scenes were drawn by Raina, and I think it kind of helped that because we had Ray and Beniam helping you out with that, it also allowed you more balance to it, having another party do the finished inking and coloring so that it didn't feel like the division of labor was too lopsided. I don't know; it just felt right. It felt like it gave you maybe more freedom or something.

RT: Beniam came through a recommendation from a friend. Any time you're working with somebody who's enhancing your own art, you definitely want to try them out and do some tests. I tried out a few different inkers on the project too. Jesse came in towards the end of the process, as lettering was the last step. All in all, as a team, we can call ourselves a real cartoonists club! We really appreciated our team.

SM: Indeed.

RT: That also includes our editors (David Saylor and Cassanda Pelham Fulton), and our art director (Phil Falco), and the whole publishing team at Scholastic. Our agent, Judy Hansen, was the book's first champion. Well, she was the second champion; I think Scott's wife, Ivy, was the first champion! But Judy immediately understood and got it. She's worked with both of us separately for a very long time, so bringing us together and finding us the right team to work with felt like she was part of the club too.

We could have put a whole extra chapter in the book about agents and the graphic novel business, but we wanted to make sure the book still hit at the kid level. There's time for all that stuff, but it doesn't necessarily have to happen on day one of your middle school cartooning club. Everything in the book is meant to be something that a kid can pick up and benefit from immediately.

Raina, you've been working with Scholastic for a long time, but Scott, this is your first book with them. So I'm curious about how that process went. And Raina, if you have any new thoughts to share about working with Scholastic now that you're working with them on a different book, and Scott your thoughts of working with this new-to-you publisher-

RT: I don't know if I have any new thoughts. But my ongoing thoughts are that they're a great team, they have top-notch editorial, and when they give you feedback, it's not just ‘oh, change the wording in this panel’ or ‘fix this tangent.’ It's not just on-the-surface edits. They're really asking questions about the meaning of the work and what our intentions are as creators.

After our first draft they basically came back and said, ‘it's not working. It's not kid-friendly enough, it's not ready. We think you're on the right track, but you need to keep going.’ So we did two more drafts, and between drafts one and two, the book went through a massive tonal shift. The first draft had Raina and Scott as characters, talking to the kids, introducing them to the concepts of comics, leading them through exercises. It felt too adult, too teachy. It just wasn't right.

SM: It was didactic.

RT: Yeah! Everybody knew it wasn't quite working, but it wasn't clear why that was. I decided to tackle draft two myself just to see whether coming entirely from my pen and working with what Scott had initially written, the tone could change. That's not to say Scott's tone wasn't good. It was good. But Scholastic was waiting for that magical kid-friendly spark, whatever it was.

SM: Yeah, and when they described it to us, they had said something about wanting it more like Raina’s other books. And at first, Raina and I were a little worried that they just meant that they wanted it to be more ordinary. But that isn't really quite what they were going for. I'm not sure they entirely knew, which is okay. It's all right to have just a vague idea, even if that can be disappointing when you first get feedback like that.

The fact that I'm such a control freak on my solo projects actually makes it easier for me to be pretty laid back about stuff like that. So I was actually ready to say ‘okay, all right. If this is how it's going to be, let's just go back in.’ When Raina dove into that second draft and finally realized that what we had to do was kill our darlings and get rid of Scott and Raina themselves, everything just became so clear. I think both of us, by the end of draft two, felt like it had been absolutely necessary and that all of that energy was now flowing in the right direction.

Now the kids were discovering things on their own to a large extent, they still had the help of Ms. Fatima but they were also learning a lot themselves. It’s like we were trying to teach the kids in the first draft, and by the second draft, the kids were teaching us what the story had to be about and everything just started to feel right. And we still did a third draft because, you know, you want it to be right-right. But that was the key moment I think: Raina jumping back into draft two and making that crucial change.

So you started making this book in 2019. Obviously, we've had some key global things happen in that meantime. You mentioned you were mostly making this virtually; part of that presumably was because we were all dealing with a global pandemic. But can you talk about how the global events are playing into your work process and the process of making this book?

clockwise from top left: Raina and Scott’s process for thumbnails, layouts, pencils, inks

clockwise from top left: Raina and Scott’s process for thumbnails, layouts, pencils, inksSM: For my family, COVID was something of what we call a cozy catastrophe, drawing us together. And I don't know, Raina, that you and I would have necessarily had a lot of IRL brainstorming if it hadn't been for COVID. I think that it still would have been mostly remote. Sure it can be fun to be in one big room with an endless stream of coffee or tea or Dr Pepper or whatever. But it just kind of works to be able to be on your own, figuring things out and then sending it out, seeing what the other person thinks.

RT: I mean, a graphic novelist’s job is socially isolated anyway, unless you work in a studio, which I don't. I've been making work basically quietly in my own studio since 2005. So this wasn't that different in a lot of ways. It's like COVID just showed other people what my life was like anyway, and I was all about it. I guess it was a cozy catastrophe. I lived alone, I had my two cats, I had a lot of family and friends nearby, but we mostly played Animal Crossing together and occasionally sat in a backyard and looked at each other from several feet away. But then as always, I went back inside and worked.

It was nice to have something to focus on during lockdown, I'll say that much. It was like, ‘well, the rest of the world is going crazy out there, but I've got this cool project and it's with someone who I really like and respect, and it's so fun to exchange ideas’ and to have – I don't think we had a weekly meeting, but we definitely had a semi-regular check-in phone call or Zoom. We weren't even Zooming before COVID! It's like we all learned how to use video chat effectively. So we were still able to sit and talk over Zoom as the book was coming together. I would have ordinarily only seen Scott once or twice in a year at comic conventions, so that amount of face time actually felt generous.

SM: Yeah, it was kind of cool, and I forgot who said it originally, but cartoonists kinda invented social distancing.

RT: That's right.

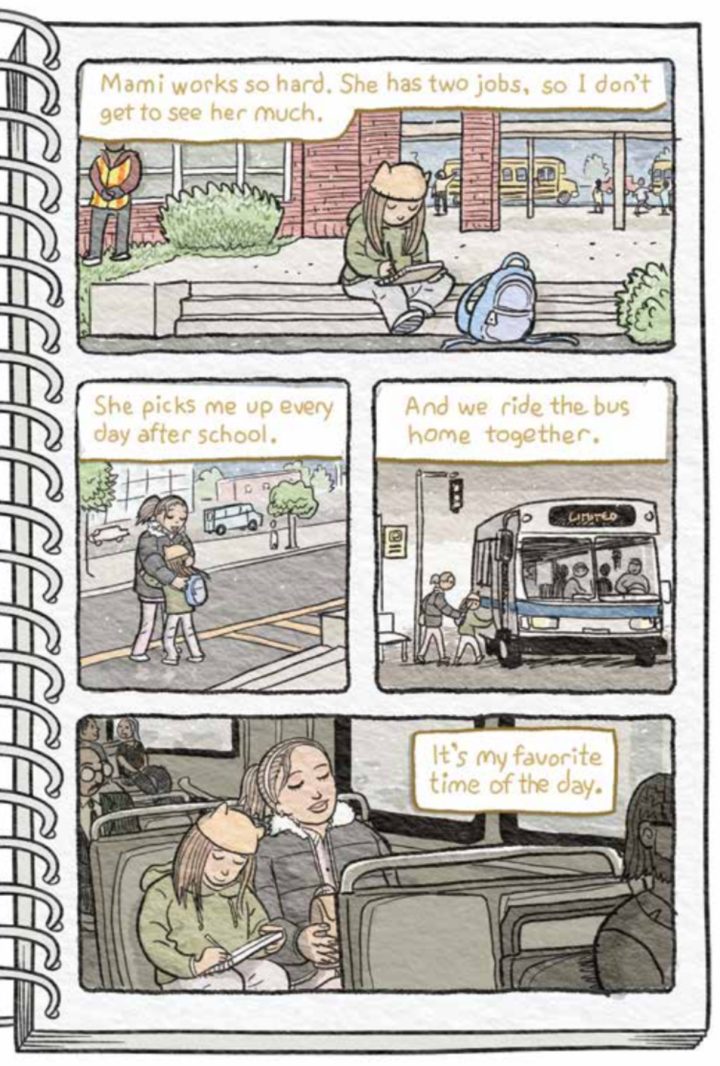

a page from Lynda’s autobio comic

a page from Lynda’s autobio comicSM: My family, we were aware of our privilege in that regard. That none of us, in fact, had the kind of job where we had to be out exposing ourselves, risking our health, as a lot of people with those essential jobs did. My daughter was working 2am at Joanne's stocking stuff, but she was pretty far separated from her coworkers.

RT: We did have a COVID storyline in the first draft of the book. We had our character, Lynda, who we knew was going through something with her family, some sort of illness. We figured, ‘well, her mom has COVID and she's in the hospital.’ The plot was sort of abstract, we didn’t know whether she would pass away or if she was just very sick, but it felt timely.

We weren't really thinking about the fact that the book would take five years to complete and publish, and that five years later things might change. Of course, they have. So in the final book, Lynda's father has passed away. It's unclear from what, just that he became sick and he is no longer with us. And Lynda only reveals that part of her story when she draws a comic about it and then shows it to her friends and they all go, ‘oh my gosh, we didn't realize you were going through all of that.’

But I think there’s truth there, in that cartoonists’ work is often what reveals their whole selves to others, or they're able to say things in their work that they wouldn't say in person.

I'm curious about how it felt for you to go from autobiographical work to more instructional work. I mean, I feel like this is a combination of fiction—which you do some of, but you’re much less well known for than your autobio stuff—and straight on how-to. How did you figure out, ‘okay, this is how I'm going to be tackling this’?

RT: I have been each of the four kids in TCC. I was a kid who wanted to make stuff. I was a kid who liked to draw. I was a kid who felt a little bit lost, but had big ideas and big passions and really wanted to share them with others, and so on. Some of the things that the kids write and draw are reflective of things that I've written and drawn, or are the kinds of comics that I might have made when I was younger. But a lot of what I wanted to do with this book in particular was to create the framing device of the characters in their realistic world, and then leave a lot of blank space with the instructions, ‘Scott does cool stuff here.’

So anytime there was explaining to be done, or charts, or graphs, or science, or explanatory anything, I would just leave it wide open and say, ‘all right, Scott, you get to finish this chapter.’

SM: And those are the places where it's easiest to tell who did what.

I feel like the part where I was reading about the infinite space situation, I thought, ‘this seems like a Scott section.’

SM: I definitely steer clear of using the word ‘infinite.’ But yeah, we do definitely talk about the blank page. The blank page to me is a pretty powerful symbol for what it's like to be a kid who's just beginning to create a rough draft for their own world. And because I've been around long enough to see generations evolve, as we were talking about, I also have come to understand that those little doodles kids make, those rough drafts do turn into the real thing in adulthood—they point to the kind of world they're going to make as adults.

On the road with Raina kids will come up and say, ‘I'm going to make comics,’ or even hand us the comics that they make, and they're deadly serious. I take them at their word. They're not kidding around.

How was that? You just have come back from a whole tour traveling all over the central and western United States – how did it go? It sounds like you met lots of kids who are excited about comics and excited about making comics.

RT: At the beginning of the tour, most kids we were meeting hadn’t read the book yet, but as the weeks progressed, more and more of the readers were like, ‘I made a comic for the first time, and I'm excited to share it with you.’’ Then they would hand us their beautiful, handmade original mini-comics. And we were like, ‘wait, wait, wait, did you photocopy this yet? Did you make copies of it for yourself at least?’’ But it was really sweet to see. We've gotten a lot of great feedback from people on social media saying, ‘my kid read this book and they just went ahead and made something. Look at how inspired they are.’

We love to see that, what kids have been inspired to make after reading.

SM: I also get to be witness to the kids—and sometimes parents and kids both—who are fans of Raina's and where her work has been passed down from generation to generation. That's pretty wild, because Raina is only beginning to see that. I probably have at least a few grandparents passing my stuff down, because I've been around so ridiculously long. But, Raina, you're just getting to that generational divide now where you have kids who might have been twelve or thirteen when Smile or Baby-sitters Club was coming out, who were now introducing their kids to you. That's pretty exciting.

Scott, have you encountered the phenomenon of these comics events with excited giant rooms of small children previously or is this a new experience for you with this tour?

SM: It's all very new. Starting in April, we did our first appearances for several hundred people, all parents and children. Our events just got larger and larger as the tour went on. So that was great. I hadn't seen anything quite like that before. And then class visits, where it's mostly just kids and a few teachers, I experienced that for the very first time a few weeks ago, when we were in Alaska. Those were the very first class visits that I did, where it's just a bunch of squirmy kids, and I think we managed to hold their attention pretty well. They were pretty awesome. But that's new for me. Obviously not new for Raina at all.

RT: It's a special thing to be able to visit schools and give kids a break from going to math class. They're super excited. And then they get to learn about something new, and see that this is a job, this is something that they could maybe do someday. I think it's really important to show my drawings that I did when I was their age, and show them that my work looks just like theirs. It's not like I sprang from the womb as a talented artist. But rather, I've been practicing and working hard my whole life. They can do the same thing. They can pick up a pencil today and keep drawing and get to that level.

SM: We want them to take away something they're going to remember. And what Raina was just saying is a really important part of that: when we were kids, we were doing something a lot like what they're doing now. Raina even gets to show a drawing of the Baby-Sitters Club characters that she did when she was just a kid. That's a really important moment. I could see a lot of kids remembering that. It's like, wait a minute. Hold on. Raina was drawing the Baby-Sitters Club, dreaming about the Baby-Sitters Club long before she had any idea that she was going to be doing that professionally.

I like to trigger their imagination if possible. We have an interactive thing where they're imagining stories from two or three random pictures projected on the screen. And we talk about our fears too, because every kid is self-conscious. They're not sure if they want to show their stuff. We want them to know that we experienced that, too. I talk about my fear of the blank page when I was a little kid. You never know what little thing they're going to remember, twenty or thirty years later.

RT: I remember magicians coming to my school, and dance troupes, poets, people doing creative, interesting things. And we felt like, ‘wow, you could actually be a poet someday. That's so cool.’ So we’re paying that forward: ‘Hi, we're cartoonists and we love it. You don’t even have to wait until you're older, you can make comics right now.’’ I truly wish that I could give more workshops and do more hands-on teaching, but making more books seems to be the best place to put my energy. Class visits are still nice to connect the actual person with the cool thing that you like, or that you've read, or that you see on the screen. It's very gratifying.

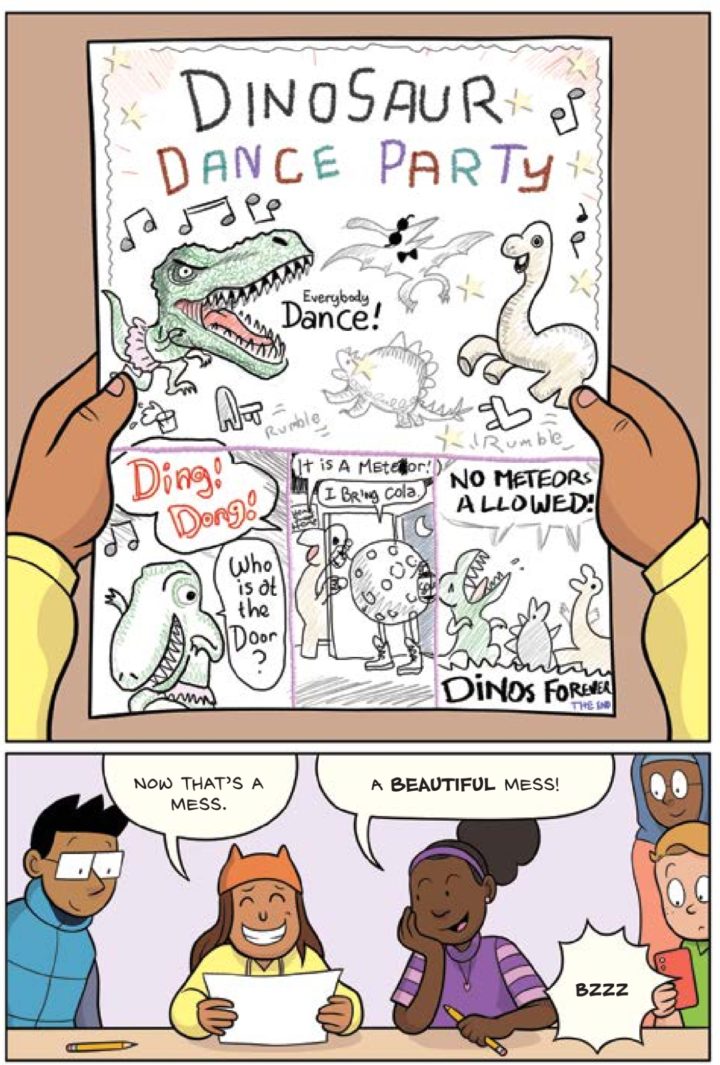

Howard’s interpretation of lunch

Howard’s interpretation of lunch

You've been working on this book for together for six years now. Did you learn new things about each other while you were on the road?

SM: There weren't a whole lot of surprises.

RT: No, I just continue to be incredulous that Scott is always Scott. Scott is always excited and thoughtful and observant and telling stories and engaging with everyone that he comes across. Our last dinner of the tour was just as interesting as our first dinner of the tour. We had a lot of lovely things that happened during our month on the road. We got word that we were on the Indie Books best-seller list. Then we had an interview that ran in USA Today, and we had a nice write-up in the New York Times. So we got to be together to celebrate those moments, and it brought joy to every single day. After a month of travel I was tired, but I wasn't tired of the work.

SM: Yeah me too. And yeah, I didn't feel worked to death. I mean, like, I've done some tours where they definitely picked me upside-down and squeezed me for the entire run. This didn't feel like that. It was a very compassionate schedule. They took good care of us. But yeah, I agree. I mean, it was just very natural, and it’s always fun talking to Raina and all the other people we would meet along the way. We were accompanied by cool people from Scholastic and other friends who would join us along the road. We would do crazy things like the Alaska Comics Camp, which was my first time, not Raina’s.

Sure, there are times when you just have to go off and be by yourself. I think that happens for everybody, but we anticipated that, and built that into our schedule so that each of us could have a little bit of alone time. I was worried that I can be ‘a bit much’ as I describe it, because I'm always a little too excited about things. Kurt Busiek once told me, ‘Scott, everything is too important to you.’ But I built that in, in advance. I said, ‘okay, we're going to have a code word so that anytime you need to be on your own, like at the airport or something just say this, and then I'll know that it's time to take a little break.’ And that seemed to work pretty well, actually.

Art gets encouragement from their dad

Art gets encouragement from their dadRT: Scott would play Wordle with his daughter. I would walk terminal laps at the airport, or go get an airport massage. Then we'd get back together right before we got on the plane. We also did rehearsals at the airport. We rehearsed our talk, I don't think every single time we presented, but we would definitely run through it beforehand every single time, just because there were tweaks that we needed to make and things we wanted to improve upon as we went. I think we got it pretty darn tight by the end.

SM: Yeah. You were very kind and accommodating with my various obsessions with presentation philosophy. I have a lot of ideas about how to put together a fun presentation. And I thought you were very sweet in allowing me to pontificate about my various ideas and to contribute quite a few of your own. And I think, yeah, in the end, we collaborated on the talk in much the same way we did on the book.

RT: Yeah.

SM: I like where it's at.

RT: I was also on deadline the entire time. I was working and drawing and keeping myself to a pretty tight schedule. Anytime we did have free time, I was like, well, ‘gotta go draw, gotta go sit in my hotel room and/or be on the plane and be working.’ But that's the life that I've given myself, as I'm usually doing too many things at once. So it was not just a book tour, it was a working book tour.

SM: And I'm in awe of Raina for drawing on the plane. I could never, ever do that. I got my twenty-ton Cintiq sitting here that I couldn't live without.

RT: I designed my workflow so I wasn't dragging a Cintiq along with me, just an iPad. So it was pretty mobile. I actually really like drawing on planes, it keeps me from thinking about the fact that I'm in a metal tube 35,000 in the air, surrounded by coughing people.

I’m curious about this presentation philosophy that you have cobbled together jointly.

SM: Well, very briefly, because we don't want to open that Pandora's box too wide, I believe that cartoonists are all born presenters if we just unlock that ability. And to do so I encourage an approach in which for every new idea there's a new image. Whenever you go from one idea to the next, you should see that reflected in the pictures. And in our talk, we used many images from the book, but we still managed to talk about much more than just the book. We brought up a lot of our general ideas about how comics work, how art works, our personal fears, the imagination that we bring to comics. So it was all very on-point as far as the book goes, but it managed to be about many, many other things. I do have this pocket rule that I try to approach all presentations with, and that is, if I don't need to think about it, I don't need to see it. I feel very strongly that an image shouldn't be hanging on the screen after you're done talking about it.

And that means that Raina and I were able to always have something to say, that the images were like flash cards at the beginning, reminding us of what we wanted to say, and that gradually we develop that into something a little bit more like a script where we would actually memorize the best way to say it after we had done it a few times. There is something very gratifying about having your presentation in such shape that you can just speak your mind in a very natural way, and the images just slide up to match what you're thinking at the time. I think that makes presentations easier to remember, pay attention to, and less likely to bore the hell out of people.

RT: It's like a good comic. The words and the images and the person on stage all need to be working in sync. In my opinion, Scott is one of the best presenters I have ever seen in my life. He's just so good at being on stage. It's rapid fire. It's a slide a second. It's what he's saying, perfectly timed to what you're seeing on the screen. It's joke heavy, it's relatable. It's so engaging, it's almost like you've missed half of it until later when you think about it and you go, gosh, he was talking about something really important when he showed those six hundred slides. I wanted to bring a level of that to our talk. Just like with our writing process, I was like, ‘here's the basic skeleton structure of what I know needs to be in a kid-friendly presentation. Then I stick in a big blank space that says, “Scott does something brilliant here. Scott does magic here.’”

SM: Of course, the funny part is that for most kids, all they're going to remember in a year is that we debated which of our pets was cuter, because I show my dog, Raina shows her cat, and all hell breaks loose because they are both very, very cute.

Raina's cat and Scott's dog- both are cute but only one can be cutest: comment below

Raina's cat and Scott's dog- both are cute but only one can be cutest: comment belowRT: The most important thing you can do in a kids’ talk is talk about your pets. Because if you don't, during Q&A, the first thing they'll ask you is, do you have any pets?

SM: Yep.

RT: What's your favorite color? Do you have any pets? What's your favorite book that you've written? Do you have any tips for making graphic novels? We wanted those to all be in the talk.

SM: Yeah, very much so.

We've been talking a lot about how you made the book and work together, but I want to pull out some of the themes. So the first one is libraries, obviously a big focus in the book. Can you talk a little about libraries and why they're cool and important and why you were like, ‘let's make this a central component of this book that we're writing?’

SM: This is a real great case of synchronicity, if we can use that ugly word in its intended meaning. Because as things turned out, the book debuted right before National Library week, and we had the honor of being spokespeople for National Library week. During that week, we got to speak at the brand new St. Louis Public Library and had a wonderful talk there. As you mentioned, it's a theme in the book. Ms. Fatima, the library media specialist at the school, is a major character and helps lead them through. The library itself is a resource, not only for knowledge, but also just as a gathering place. So yeah, and I think it was partially a love letter to libraries, because librarians, like teachers, like many parents, have been so tremendously supportive of comics from that summer of love till today, over these last twenty years, which corresponds to the twenty years of Graphix as well. Libraries have been part of the revolution.

RT: It's almost a cliché at this point to say, ‘the superhero librarian.’ Librarians have been championing comics for a really long time, and they have been some of our biggest supporters from the early days. A lot of librarians are geeks and love comics, love to dress up, and love to attend cosplay contests. Many libraries have started hosting comic conventions that are free to their communities and encourage kids and families to come in and take drawing workshops and have their own costume contests. So there's this proverbial image of the librarian as a superhero.

And in my head, Ms. Fatima is secretly a superhero. She's the most magical character in The Cartoonists Club. She's the one that can pull rabbits out of nonexistent hats, and she can sweep the kids off into the galaxy to show them how time and space work. She has magic up her sleeve. Of course, because I'm working with Scott here, the whole thing is very meta. Stars appear when she talks about the magic of comics and the kids are going, ‘oh look, stars, why are they hitting us in the head.’ But it's really nice to now hear back from librarians who are reading it with their kids, and they're feeling that sense of pride, like they have a character who's as cool as they know they are—that the cliched ‘shhhh’ librarian is not what most of them do in their daily lives. They're really out there being superheroes for the kids in their library and for their whole communities.

SM: Yeah, that institutional awareness is definitely a part of that. The revolution of the last twenty years is that museums, libraries, schools, all these different institutions have just been on our side. They've been our allies. Not every single one of them—and.yes, there are the occasional comics-allergic teachers or librarians or parents—but that's okay. And in fact, we even have a parent who is skeptical of comics because it's not an unreasonable position to take for a parent.

RT: In the story.

SM: Yes, in the book. But they come around somewhat during the course of the book. As we've found many parents have, when they see their kid beginning to read and developing a love of reading from comics.

RT: What we didn't know when we started this project is that it would debut in 2025, where books are being banned, libraries are being challenged, and librarians are being told that by simply doing their jobs they are a danger to readers. It's weird that TCC landed in this atmosphere, where people are feeling a ton of fear and concern. But we've written a love letter to libraries and why they're essential. So it stands as a counter message to all of that, at least I hope.

SM: We stand out a little just somewhat accidentally. Ms. Fatima wears a head scarf. Our kids are a fairly diverse bunch of kids. This was not any massive, deliberate decision on our part.

RT: Nope.

SM: It just seems to stand in more stark relief now in 2025 than perhaps we realized when we were making the book.

Making art that accurately reflects the American population is now a polarizing choice.

SM: Yeah, and reflecting the nerd population, this is our community. We know these folks.

Community: we've talked about it before, but also it's a big theme in the book itself. Is there more that you want to say about comics and community and the importance of comics and community? You've been talking about just getting back from Comics Camp Alaska, and the community there; I think it's something that you've kind of found throughout your careers in a number of different ways.

SM: The only thing I'll add to what we've said so far is that at sixty-four, I'm carrying out a plan that I really hatched when I was in my twenties, which was to continue to think of community in multigenerational terms. Because the older artists, people like Will Eisner, that I had met, seemed to internalize that idea that the kids just coming in were their peers. And I had already felt a sense of kinship with artists who were very old or even dead when I started making comics. And so I knew that if I was to stay healthy, I would gain more benefit from my community if I saw it as this flat, non-hierarchical fellowship of the people who make comics. We talked about that a little bit up at Comics Camp. There were some very young artists, some older artists. (The older artists were me. I was probably the oldest.) But we were all peers. And I hope it continues this way. There’s a strong sense of collegiality right now. It's good, it's healthy, and it keeps me from feeling old and depressed.

So I also want to talk about comics art festivals and small comics festivals, because that's a big theme in the book, too. It ends with a comic show at a library where the kids get to show their own work. Can you talk about how comics and festivals are important to you and the work that you do?

RT: One of the big inspirations for the book is a real comic convention at a real library. That's A2CAF, in Ann Arbor, Michigan, which used to be called Kids Read Comics. I've been attending since the late aughts. I can't remember the exact first year that I went, but it was right around the time Smile was published. It was put on by two comic shop owners, a comics librarian, a comics teacher, and a comic book writer, and they got together and said, ‘let's make something free for kids.’ They started hosting this event every summer, and I started going. That’s where I really felt the kinship and community that we've been talking about.

The most important thing was that the organizers wanted to erase the space between the person behind the table, and the person in front of the table. They wanted it to feel like a kid could have a conversation with somebody who was really famous and feel that they were their equal. And that pro could come around from behind the table, and sit down on the floor with you and make a drawing. Creators were given free tables with the expectation that we would do activities, workshops, and panels with the kids. So the spirit of giving was there. The spirit of community and equality were there. It was chalk drawings on the sidewalks, and making funny hats together, and doing readings.

Another lovely thing about it was that kids could table. Jerzy Drozd, who is a comics teaching artist, had all these cartooning students in classes that he was teaching. The students were making their own comics, and often they would come and they would exhibit at A2CAF. They would be sitting right next to somebody that had been making comics for forty years, and they were on equal ground. My cartoonist friends often brought their own children to sit behind the tables with them, not just as ‘oh, this is my little assistant,’ but ‘this is my fellow cartoonist.’ I can't explain how much it has meant to me to be a part of that, and to see that and the love and the joy that everybody brings to it because they know that it's important for these kids. A2CAF was the first place I saw it happen. Now they are everywhere. The library con is a real thing, and I wanted to pay homage to a place where families and kids can go and learn and share. And where maybe that one parent, who's a little skeptical about graphic novels, can take their kid because they know he’s going to love it and then walk away so, so excited because they found a mini comic together about ornithology. I always feel so invigorated by that environment and that community. I wanted to show the kids in our story really coming into their own in a similar space, where there was no difference between them and the really famous cartoonists sitting next to them.

It's a place I return to again and again, simply because I like to be there. I went a few years ago and didn't announce that I was going. I just quietly snuck in, wearing a mask because it was high COVID times, and sat in the back and watched Gale Galligan give their presentation as a special guest at A2CAF. I just basked in the love and glow of kids and cartoonists in the same space.

SM: I should mention that Thousand Oaks, California, the town that I was living in until recently while I was doing this book, just had a library con that they began just in the last two years. Their first guest was Jen Wang and their second guest was Kazu Kibuishi. So I got to see a couple of my old friends be headliners at the Thousand Oaks Library Con. It's hitting home for many Americans.

RT: It used to feel like you had to go to San Diego to find that community. But now that community is probably somewhere very easily drivable from where you live.

Makayla and her fans at the comic-con

Makayla and her fans at the comic-conSo what are you working on now, and is there anything that you want to share about that?

SM: I'm still working on a massive book about visual communication. It's several hundred pages long. It's gone through four drafts. There may be a fifth. We'll see. And it may or may not be one book, we're just making the final determination on that one. So it's a gigantic project. I like to describe it as dragging my ship over the mountain. These things, sometimes they take years. But in the middle of it, I did The Cartoonists Club. So every once in a while you can do two things at once. Apparently I can walk and chew gum at the same time. But yeah, I'll be getting back to that gargantuan undertaking pretty much immediately.

RT: The next thing for me is Facing Feelings, which comes out in October. And that is the companion book to the art show, Facing Feelings, that was up at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum in 2023.

Another library space strongly associated with a comics festival.

RT: That's right. The gallery show was curated by Anne Drozd, and it was incredible to be a part of. It was a retrospective of my career and not only showed original art from the work that I've published, but also work of mine that has never been published: mini-comics, childhood art, inspirations, ephemera, and the story of my career, but also comics through the lens of emotions. There’s a big interview Anne and I did. And Scott actually wrote the foreword to the book, which is pretty cool! And the whole thing has my annotations from the exhibit. So for the kid that wants to learn about the stories behind the stories, Facing Feelings is it, and it's being published by Graphix in partnership with the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library. It's a project I've wanted to be out in the world for a long time, and thanks to the show and thanks to the Billy and Scholastic, it's almost here.

Final thoughts?

RT: I'm just proud that The Cartoonists Club exists. We made this book because we wanted it to exist. I'm so thankful that we saw it through and put it out there. It truly felt like something that I had to make to happen in my career, before I could move on to the next thing.

SM: And I am proud that it has a coherent identity, because it's hard for a control freak like me to allow for the kind of creative process that just lets something come together in its own time, with many variables, and through collaboration. I like stories as a reader where you only fully appreciate what the story was about when you’ve turned the last page, and from a process standpoint that describes this as well; that it was in the making of it that we discovered what kind of a beast this was. And there's something very gratifying about that.

The post ‘What do you think would happen if we combined <i>Smile</i> with </i>Understanding Comics</i>?’ Raina Telgemeier and Scott McCloud have the answer appeared first on The Comics Journal.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·