Alex Hood, who draws under the handle Haus of Decline on X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, and Bluesky, is one of the internet’s most prolific, weird, and funny cartoonists. Hood’s cartooning shows a mastery of comics akin to Nancy’s Ernie Bushmiller, or Krazy Kat’s George Herriman. Her style is simple and cartoony, relying on largely minimalist figures with heavy black ink linework existing in large, white voids. Most Haus of Decline comics are four-panel gag strips similar in form to other newspaper strips, although their content would likely bar them from any widely circulated paper.

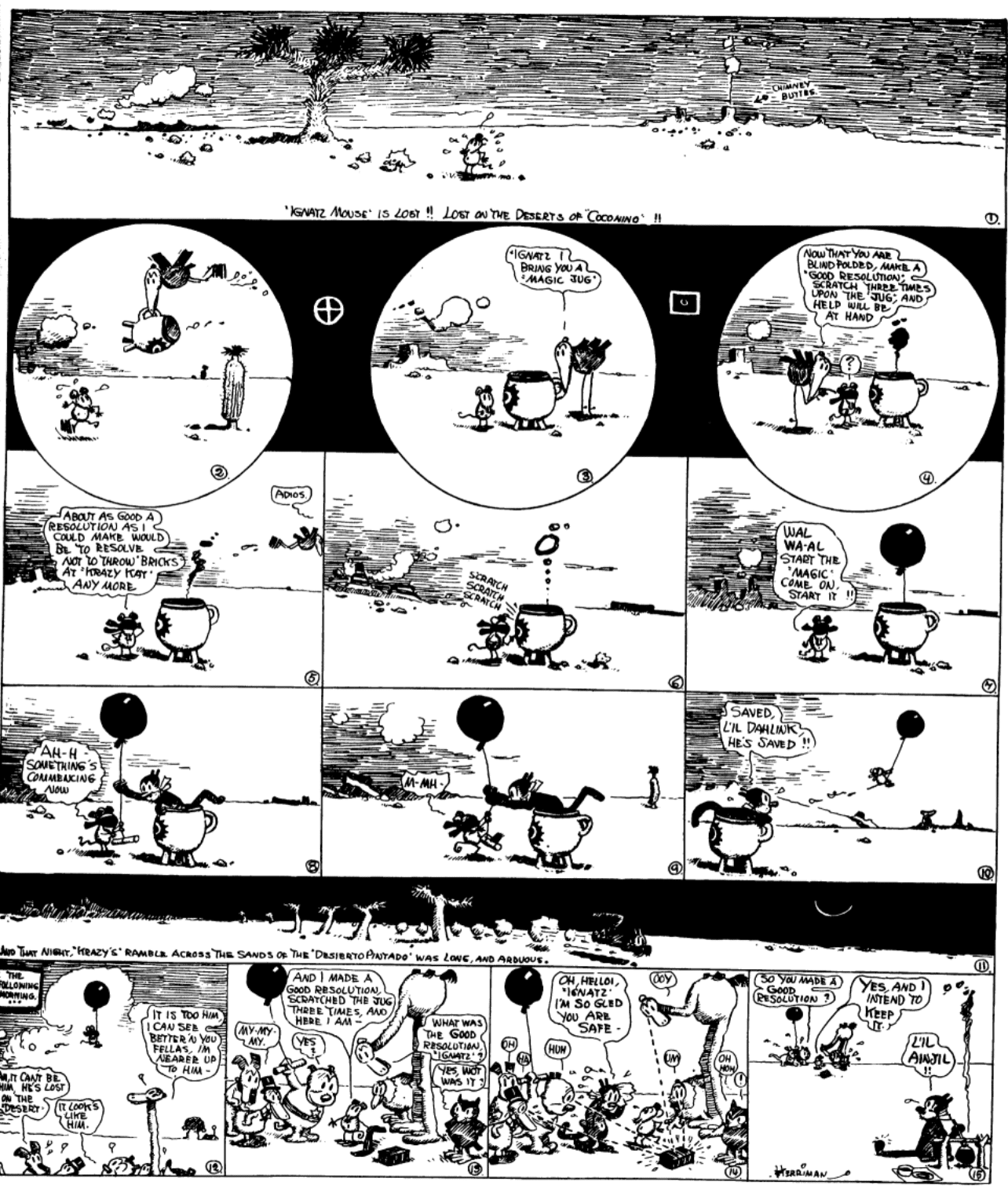

In much the same way that a syndicated newspaper cartoonist might forgo complexity in their style for hilarity of a joke and to meet the obscene workload of a daily strip, Hood’s style makes Haus of Decline all the more impactful. Hood has mastered the ability to provide a reader just enough detail in her characters and environments to make each strip tangible and give it depth, without distracting or overwhelming the eye. In our interview, Hood touches on the importance of interesting horizon lines, citing work by Herriman as the pinnacle of the practice. Herriman’s characters are often stranded in a vast, Dali-esque desert with a distant sketchy horizon, a setting which underscores the size of the full newspaper page Herriman had to work with.

Hood on the other hand, often opts to obliterate a definitive spatial or environmental horizon, drawing her characters in an endless void. The vanishing point of the comic becomes the top border of each panel, rather than a diegetic space, like “Chimney Buttes” in the Krazy Kat page below.

A page from George Herriman’s legendary newspaper strip Krazy Kat.

This kind of horizontal play is an example of the many ways Hood calls attention to the very form she works in. By creating a horizonless world—a spatial impossibility—Hood underscores the necessity of comics in creating the world of Haus of Decline. Just as Krazy Kat’s otherworldly horizon alerts us to a world in which a cat might pop out of a magic jug so a mouse can float out of the desert without batting an eye, Haus of Decline’s broad white expanse suggests a universe of infinite creative futures.

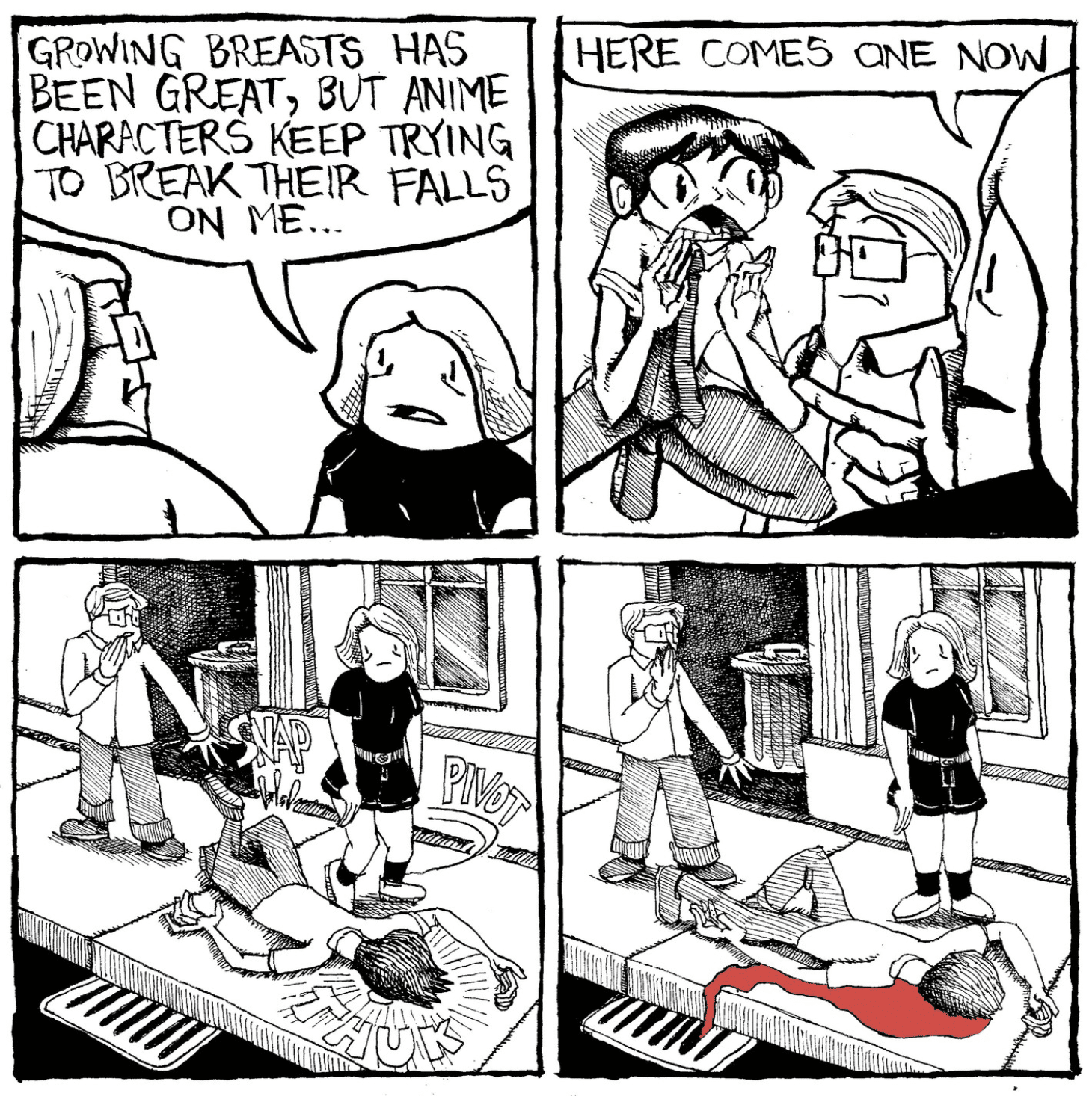

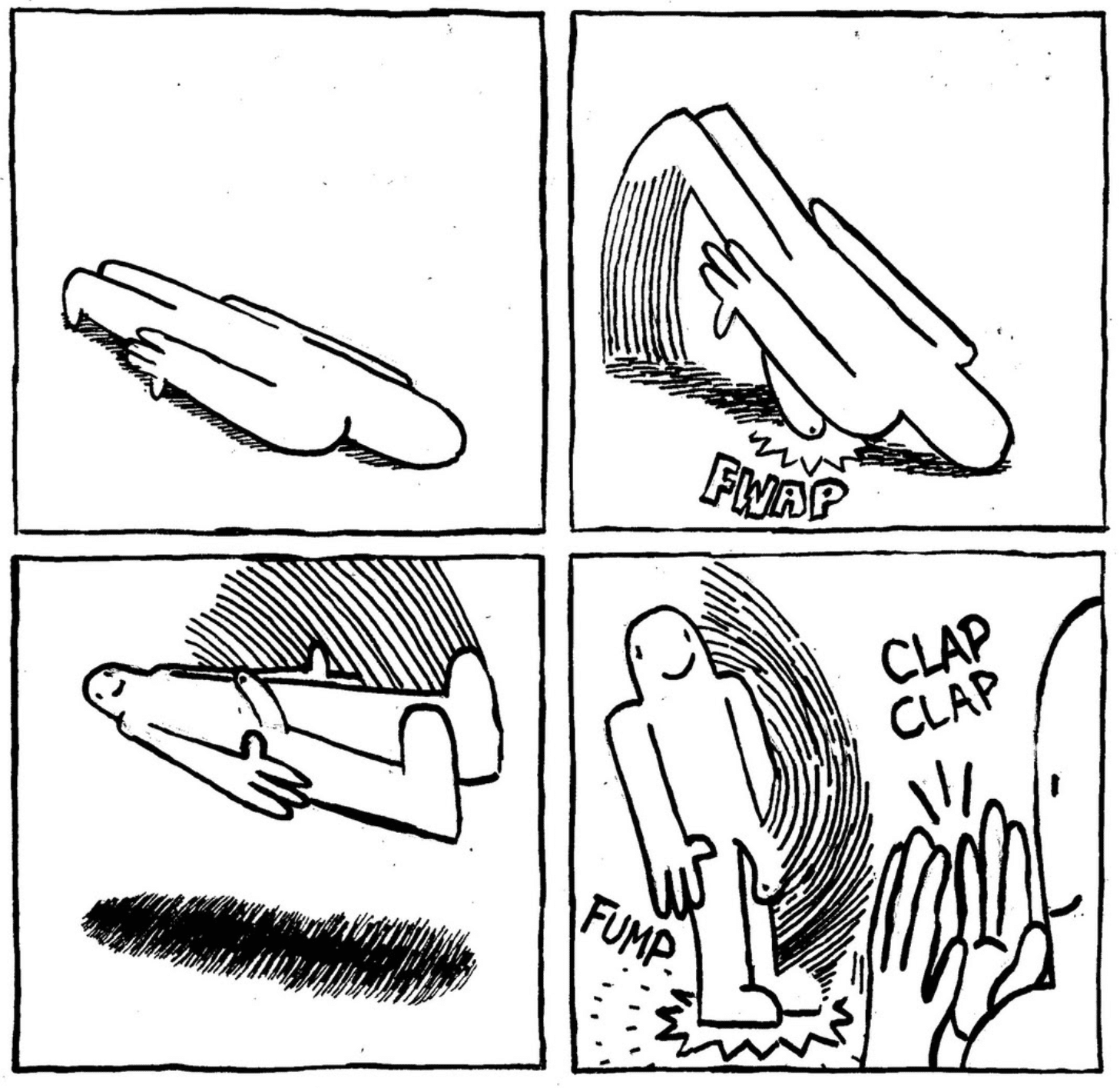

For Hood, the void is part and parcel to the kind of utopian world she builds in her comics. In Hood’s utopia there is not a liberation from trans- and homophobia, along with all other oppressive systems. Instead, Hood imagines and disseminates a world in which a person does not need to struggle to assert their identity, or the fluidity therein. Hood’s characters are suspended in a kind of timeless queer utopia, where the grotesque, lewd, and downright strange can exist without even the consideration of judgment. In Haus, there can be no sense of liberation, because there is no sense of oppression or restriction, only of constant boundless evolution. Anything goes.

In Haus of Decline, transness is often a central subject, but Hood rarely if ever chooses to focus on real-world difficulties of transphobia.

I sat down on Zoom to talk to Alex Hood in late October from her home in Toronto about her evolution as a cartoonist, her influences, and where she sees her work and comics culture as a whole going in the future. This interview has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

Tate McFadden: You don’t do many interviews.

Alex Hood: As you’ve found out, it’s hard to reach me. I’m very itinerant and I’m bad at self-promotion because I get scared of branding. Everything pushes you to be a fake version of yourself. I got to 15K followers on Twitter, and I immediately started Millennium Actressing. I was like, who is real, and who is the role? Who is I? That’s why I have these Bill Watterson crank ideas about merch or self-promotion because I see other people doing it. And even just the culture where if you’re a trans woman, you post a selfie, maybe you look good and even that is a constant contribution to this culture of essentially capitalist self-reproduction. ‘Look at me, look how glamorous I am, look at this sort of aspirational lifestyle.’ And do I want to play a part in that? So that’s why I don’t do interviews. Also, I’m very neurotic, so you ask, ‘why don’t you do many interviews?’ And here’s my 7-hour answer to that.

I post a lot of selfies because I’m very narcissistic. I like it when strangers tell me I’m pretty. It’s very nice. But the compliments are also part of the sickness, right? Why is this a normal social interaction? To post a picture of myself. And then people share it. Why is someone, for example, retweeting a photo of me because as far as I understand Twitter, you use it for blogging or whatever, so I’m just part of someone’s blog now? Just a woman? It’s kind of depersonalizing in some sort of way. And I don’t think anyone else needs to have the neuroticism about this, but to some degree, I do feel like a lot of tech giants just tricked us into engaging our own sense of narcissism in order to collect data about our appearances and locations more easily. It’s like ‘Ooh, I get a lot of free dopamine from this, and all I have to do is allow someone to make deepfakes of me.’ Which they have done. People have made deepfakes of me.

McFadden: You made it, you’re huge.

Hood: I’m huge now. People have stolen my appearance in order to make very disturbing things. I knew that would happen, and once you do that, you can’t go back, right? I call it self-brand, but everybody does that on social media. Everyone has become a corporation unto themselves. You’re not just you, you’re the Wendy’s version of you. You know that episode of Community where Subway is a guy? Everyone has become that version of themselves. I’m ‘Subway me.’

It’s weird, you find people acting like that persona in real life, too. It’s not just something that they take online, they take that sort of cloud networking, hustle mentality, and it pervades all social parameters so that this detachment, or a lack of tenderness is very apparent in their behavior and I catch myself acting like that if I’m not careful.

McFadden: A lot of the people who make swipe comics use that as a jumping-off point to move to physical media. You have a zine or two out there, but you’ve mostly stayed online. Have you thought about that transition at all?

Hood: The answer to why I haven’t is sheer laziness. It’s also my sick anti-merch sentiment, which is ‘Don’t Buy Shit.’ It’s already online for free, you don’t need a little fucking piece of shit clogging up your house arteries. It’s getting real for trans people. You gotta cut and run. You can’t be weighed down by no Haus of Decline book, you know? You might have to cut and run at any fucking time. And I know that’s stupid, I know that’s this incredibly ludicrous anti-consumption mentality.

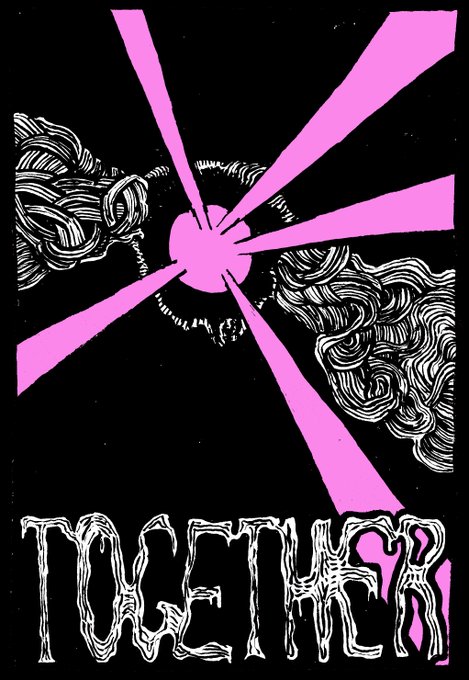

I was going to do stuff. I have a slow pace and I really lost pace with work upkeep due to mental problems. I had just assigned myself this crazy amount of consistent daily work, including the comic and making a podcast, and doing commissions and trying to organize IRL shows. So all of this stuff was happening in the background and the book that I wanted to do, and I had planned to do, was my graphic novel Together.

I guess I should explain that I wrote a book. My first ever graphic novel. I’m very proud of it. It’s rough around the edges because I’m an amateur, but I’m proud of it. I think it’s good. The premise is that a couple wakes up and they get their fingers stuck together, and they’re slowly gooping into each other as time goes on, and what’s the mystery behind the gooping? Will we find out? How does it progress?

Then this movie comes out with Allison Brie and Dave Franco, the good Franco, the noble Franco. And it’s the same premise, and it’s also called ‘Together.’ And at first, I’m freaking out, because what the fuck? But it turns out the guy who wrote and directed it had a script registered with the WGA[2] since 2019, so I can’t even complain about this. What’s also weird is that another movie sued the Together movie for plagiarism. It was embroiled in another plagiarism scandal, to which the guy that did Together said, ‘No, I’ve had it registered since 2019. You’re not the first to come up with this premise.’

So I didn’t want to fucking publish the fucking book anymore. I got so bummed out, because people are gonna think ‘ah, you took it from the movie.’ The thing that I really need to do, though, is just publish a compilation of the cartoons. I see value in that. I need to get off my ass and do that sort of thing.

McFadden: Maybe you’ll have a Fantagraphics library after you die. Like how Gary Groth published The Complete Peanuts.

Hood: Oh, I would love that. Yeah, in a big square book.

McFadden: Some of the forwards are big, too. Like, Barack Obama did a forward for the Peanuts book. You could have Bernie or something.

Hood: I don’t know, soft Zionist Bernie Sanders, we’re not getting Bernie… what politician would I get? Who is my dream forward? George Corpse Grinder Fisher. From Cannibal Corpse. What if we had a different soft Zionist? How about Jack Black? I keep doing Zionist Jack Black.

McFadden: Has that appeared in a strip yet?

Hood: No, no, I don’t make Palestine jokes. Before October 7th I made jokes about it but those are rough jokes right now and I haven’t made any comics that joke about it because I haven’t found a way to do that that doesn’t make me sort of sick. It’s fine to joke about it, you’d see Palestinians making them even as they were facing hell. Guys like Refaat Al Areer[3] up until they fucking killed him, were making jokes. I don’t want to begrudge other people for doing that, but especially in the comic form, where it’s gonna be there forever, I haven’t figured out a way to thread that needle where it’s funny, but also spiritually righteous.

It’s like the way the phrase ‘spiritually Israeli’ has become this sort of meme thing. I get it, we all have an idea of what that means. It’s become sort of a new version of Reddit. Just to say that something has the chintzy quality of Israeli culture, it comments on the sort of fake dead-eyed quality of the people that are attracted to Israel. The Michael Rappaports, Brett Gelmans and Dicaprios. That sort of cheap, smooth and very consumptive quality, but [‘spiritually Israeli’] has also become this sort of jokey shorthand as well. People talk a lot about irony poisoning. I don’t even think this is irony. This is more like a total inability to take any event seriously. You should joke about stuff, but for [irony to be] your first and only reaction to it because you essentially feel powerless is to diminish its power in your mind.

I do this all the time. I am just as guilty of this as everybody. You can’t not laugh about it sometimes, just in order to live and in order to not get bogged down with pessimism. Just so you can move?

McFadden: Making art about trans people or queer people is, of course, a political act in and of itself. How do you see your work within the realm of political action? Do you consider it activist?

Hood: I’m always thinking about this because I don’t know if you have the thing where it’s like, ‘Okay, the world’s on fucking fire. I’m not good with rifles. What’s my skill? What skill can I apply to, like, trying to make the world better?’ And what if you have a very weird specific skill?

I am kind of good at mass communication somehow. I don’t know how that happened, I was very lucky. So there’s that idea in your head. You get that weird sick ContraPoints idea in your head, which is like, ‘I can talk to the great unwashed. I will be the one to articulate my humanity to the great unwashed.’ If you’re starting from that point you’re gonna lose. If you think that you’re going to be persuasive. I think you need art in order to articulate. You need it as propaganda, but not just as propaganda. I think it is worth it to try and find the right combination of words to evince your humanity in order to avoid a bloodbath. I think that is a noble goal.

Because there is that sense, right? In the current climate, the vampiric nature of capitalism will yield class violence in an unprecedented way that we haven’t seen since the early 20th century. Having grown up in relative comfort, I would like to avoid that if possible.

Trans people have become the figure of microscopic hatred amongst the current ruling class. And as little Sartre says ‘anti-Semitism is the socialism of fools.’[4] It’s the same thing, transphobia is the socialism of fools. All these have been ground down to a fucking nub. by the current late-stage mode of capitalism, but we are in a society which tells us ‘capitalism is good. If you fail in capitalism, it’s your fault.’

So then, whose fault is it? It’s trans people’s, right? Then there becomes that desire to demystify oneself, to actually say ‘I’m normal! Look at me! Don’t worry about me!’ But easier said than done. I’m not going out with my big sandwich board to, you know, Greensboro to do ‘Ask a tranny anything you want to know!’ That’s not happening, I’m not doing that. There’s this illusion that if I just articulate my humanity in a casual way enough then maybe I can win people over. But I don’t think you can consciously do that. If you’re going to try to do that consciously, you’re gonna fail. You just sort of have to live and be a cool person, self-evidently. You can’t tell people that you’re human, you have to show people, unfortunately.

McFadden: That touches on the pressure that anyone in an oppressed minority group who is writing about their community has to make themself legible. The pressure to make myself transparent for you, explain everything to you. So much of what you’re making references really eclectic or niche trans or queer cultural touchstones. It seems to me that pressure and those references are at odds, how are you engaging with that?

Hood: So I’m very much inspired by the work of Keith Haring, obviously. Anyone that managed to, sneak in gay culture into the mainstream just by being hella fucking cool like Rob Halford. Guys were dressed in leather and studs like in Judas Priest as if this is the most heterosexual shit on Earth. And there is a question as to whether that actually does something about activism. Whether this hidden queerness that Keith Haring represented, where you’d go to Nebraska and you’d see people with Keith Haring sweaters in the 90s, just because that was the style at the time. It was just the mode, not knowing that even embedded within those characters, I see this inherent queerness, to his art. What I liked about it was it was this expression of pure joyfulness. Even in the midst of AIDS, it was this idea of freedom, and that [Haring] was envisioning that, in our base state, we’re these sort of innocent animals. And I love that.

Something that stopped me from being trans for a while was there was this sense that you had to be some sort of mystical ethereal elf thing in order to make it work, as opposed to me, who’s just some Midwestern rat bag. You had to be educated and erudite and I didn’t see any archetype that represented where I was coming from and where I still wanted to be: gross and dumb, even after I became a lady. What helped me was Eddie Izzard said, ‘I’m a male tomboy.’ I first heard him say that, and I was like, okay I’m that. God, it’s sad whenever you see her on, like, interviews where she’s caping for all of her very transphobic friends.

I think the first and sole archetype that I was sold of trans women was ‘glamour princess.’ Either that or Buffalo Bill.[5] It’s one or the other. It’s either Hunter Schaefer or Serial Killer. I always wonder why there doesn’t seem to be a ton of prominent media where trans people are hanging out, and nothing is super dire. They just sort of exist in society. And not just amongst trans people, they’re, integrated within their communities

Canada, for some reason, loves exporting cozy pastoralism, it’s like our bread and butter. Schitt’s Creek, Corner Gas, Letterkenny, even our best offerings in Trailer Park Boys have that air of cozy pastoralism to them. There’s something about ‘we’re solving mundane problems in a small town.’ Canada keeps pumping out this one show over even shows set in urban settings, like Kim’s Convenience, have that quality of ‘Oh, we’re just a little small town in Toronto, and we’re just getting by day to day.’

Whereas American shows are all like ‘we’re all dying right now, but we live!’ There’s that real sense of direness and urgency to [American TV]. A lot of these shows will incorporate queer characters, but oddly for a rural setting, the characters will be entirely accepted and their identities will not be a source of tension within the community. And I love that fantasy. I love that weird Canadian woke pastoral fantasy. We had a show called Little Mosque on the Prairie, and it’s exactly what you think it is. I think there is some value in showing idealism, a vision of peace. A vision where your issues can still exist, but your identity is sort of secondary to you just existing within the community?

McFadden: How do you see that sort of appearing in your own work?

Hood: One thing I like is that my characters basically all look the same. There is a very little differentiation between the male and the female characters such that usually, even if there’s tension in the strips, everyone appears the same. There’s another guy that has this quality, Pants. The essence of his cartoons is that everyone exists in this world where there are these whimsical social mores. And that was sort of my beginning of the cartoons with the penis guys, that everyone just sort of exists in this world where no one is ashamed of their body.

A Haus of Decline strip from August, 2024. Hood’s work often features incredibly simple ungendered characters existing in a blank void completely nude.

Everyone just gets to go around being weird and gross without fear of hatred or repercussion. There’s a sort of freedom aspect of that, but as the comics evolve and I transition, they become ‘My Femcel Trans Chungus Life’ comics because it’s like, ‘Oh, I’m a person now!’ I feel like I can write about my own experiences and not feel like I’m lying anymore so you start seeing more detail in the comics.

My ‘Trans-Chungus Autobio Fun Home Bechdel’ comics are my bread and butter. That’s what most trans artists are doing, but I see an immense value in doing that. I think that is our trans webcomics pastoralism. I also see an immense value in not only doing that, but I’m always encouraging the kids. ‘Do physical media!’ Because then you can put it away somewhere, and the Nazis can’t erase it. Algorithms can’t do it. More than anything else there just needs to be documents that you existed. Be comfortable being mundane and documenting your mundanities Not everything needs to be like Ethyl Cane, or SOPHIE. That image of glamour lady where everything is fucking heightened.I want to deliberately push against that, because I see it as the maintenance of the system that’s designed to keep us down. It’s a capitulation to the idea that our lives need to be this epic money-spending ceremony.

McFadden: It’s a very utopian vision. There’s no sense of sexual liberation in your work because everyone’s just living their life.

THAT scene from Gummo

THAT scene from GummoHood: In that respect, this is going to be an odd comparison, but it’s like Harmony Korine movies. Harmony Korine is an objectionable guy and I’m not saying you gotta like Harmony Korine, but I am a sicko that enjoys Harmony Korine movies. If I ever make a movie, I’m gonna have a scene in it where they’re watching the scene in Belly, where they’re watching Gummo. What I like about Harmony Korine movies is that his characters don’t have arcs, they just exist and you’re just seeing vignettes of their lives that are already very fulfilled. They don’t need to change as people. That’s the beauty of one-panel comics, too, is you’re just given glimpses into this other world. This world that is, perhaps, better than our own, because people are integrated and their desires are fulfilled in a way that our desires cannot be, because our desires are constantly mediated by our relationship with this hegemonic overlord of capitalism. Whereas in the town of Xenia, Ohio, in Gummo, they got a whole different measure of what is and what’s not success, and you sort of, like,

Or in Trash Humpers, it’s like, ‘why are these people doing this? It seems like they’re doing this just because they’re doing this.’ And I think that’s the idea. You can just be something without regard to your overall place in the capitalist superstructure.

That’s what’s beautiful about the Addams Family, is that they love each other, and I mean, that’s the gag, is that they are a well-adjusted horror family, you know? This other world where people are fulfilled, but what makes them fulfilled is an entirely different ruleset than what you’re used to. When I was on the outside looking in on the world of trans people, there was that sense of ‘You found joy using a different set of rules than I have become accustomed to, so what if I just changed the rules for myself?’ That was a big revelation. The idea that you didn’t have to be married to this code that had been implanted in you, or that that code was illusory and can be changed at any time. Which is why I like visions of this other world where people have found joy subscribing to a different ideology.

McFadden: A lot of cartoonists in general, but especially cartoonists making swipe comics blur the line between memoir and fiction. It’s a predecessor to the swipe comic, but Allison Bechdel’s Dykes Watch Out For is an example of that. Your work feels very lived and true to life in many ways, despite its absurdity, are you thinking about that fact/fiction boundary when you’re working?

Hood: I think memoir is absolutely an apt term. I call it my ‘femcell trans chungus life,’ but memoir is a much nicer term for it. My friend Remy [Boydell] wrote The Pervert[6] and it sparked a huge Twitter discussion of, ‘why are comics so uniquely good at autobio?’ Or ‘why do autobio comics tend to be like Fun Home, or The Pervert, or Maus, even. I was thinking about it hard, and I think, to me, what comics are uniquely good at is capturing the perceived quality of memory.

Whereas if films are capturing the perceived quality of dreams because they flow like dreams, because they move continuously like dreams, comics have that Proustian sense of trying to recall something. And it’s an image, and there is a phrase associated with that image. Like, the very format of words and pictures mimics the way that memory works. And maybe I’m just saying that because comics have influenced the way that I perceive memory, but I think a lot of people who aren’t comics-influenced have that when they think of memory. They think of a phrase associated with an image or a sense, or a touch, or something like that, but usually there is some sort of linguistic marriage to some other sense, some synesthesic thing has happened. I think comics do that really well, better than any other medium, by virtue of the fact that you’re obligated to have words and pictures in the same piece of art.

McFadden: You’ve mentioned that as time passes since your transition, your comics become more detailed, perhaps even more naturalistic or realistic. What do you think of the juxtaposition between minimalist cartoon figures and your other absurd, even grotesquely detailed style?

Hood: I get that from problematic fave John Kricfalusi. Ren and Stimpy was—unfortunately, we know [Kicfalusi] is a bad guy. All of my comics series from the 90s. Oh, what’s Doug Ten Nappel up to? Oh, jeez! What’s Dave Sim up to? Ah, jeez, you know? Why am I- why are these guys like this? Why am I picking these guys? Is there something wrong with me? R Crumb, especially…I thank God my subconscious is a bit goofier than theirs, it’s a little less intense.

I think sometimes the drawing can be the joke. Sometimes a punchline won’t work until you have the accompanying drawing with it, and then it works. That’s the maddening effect of comics—I don’t know if a name has been given to this—But it reminds me of the Kuleshov effect in film, you know, the Kuleshov effect?

Early Russian filmmaker Lev Kuleshov noticed that if you take a guy with a neutral expression, and then you put happy scenes surrounding him on either side of him, then the audience will interpret him as happy, and if you put sad scenes on the either side of him, the audience will interpret it as sad. So it’s basically making a point about how using montage contextualizes different images. All the images are contextualized within each other. And in the same way if you have words with different pictures, [they] mean entirely different things. I think that’s also the quality of comics, which is sort of special, that you can really manipulate the meaning of words by showing a character do an entirely different expression. You can make something much funnier, for some reason. Even though it’s the exact same phrase, and the phrase itself isn’t very funny. That’s the gag a lot, when you have these simple characters, but then their faces morph into these grotesqueries. I think that provides that visual punchline, which you also need. I mean, I have these for what makes a good comic.

I try to abide by these, and I’m always breaking them, because you have to:

There needs to be at least one sort of visual element, or one visual gag in it. It can’t just be talking heads. As much as you’d like to do talking heads. There’s plenty of people that do talking heads comics, and it works. But this is for me. If you’re not using what the medium is capable of constantly, i.e. the visual aspect of it, then why do comics at all? Why couldn’t this have just been a post? So there needs to be a visual element.

There needs to be a punchline. It can’t just be that no punchline is the punchline. There needs to be a little hit. That is the reason. And this is just for four-panel gag comics. This isn’t for any other format other than this very, structured format.

Avoid references as much as possible. Especially specific internet references. If you have to make a reference, do something that stands the test of time. Otherwise, your comics will age really quickly and untenably and cringely, you know? And I’m always breaking this, I’m always making reference to things that are popular within the moment. That’s the game, because you feel motivated by the algorithm: ‘Everyone’s talking about this, so I have to say my little piece on it, too.’

So, sometimes I end up making funny jokes as a result of that, but I try to avoid that, because I also see it as cheating a little. If you do a comic on a subject that’s really popular in the moment, of course it’s gonna game the algorithm. So, if you can manage to do it, if you can manage to do something totally unrelated to whatever the current discourse is and it still hits, then that’s the good feeling.

I emphasize simplicity. Simplicity is good.

There was a whole internet debate about too many words which I got really angry about, you know, because that adage isn’t even correct. You should, you know, turn your mind towards editing and being concise, but in that case, there weren’t too many words.

McFadden: You mentioned a few of them like Dave Sim and Ren and Stimpy, but can you tell me about your early comics influences?

Hood: A lot of that stuff came later. In terms of childhood stuff, I’d say that the first guy who I really loved, and his influence is evident in my work, is [Gahan Wilson] because my mom was a fan of New Yorker comics. She bought me a Gahan Wilson retrospective which is a very odd book to give a kid, but he had done children’s illustrations, too, for those kids’ horror books that were popular at the time and I loved that. I still have my childhood copy of the Gahan Wilson, Still Weird collection. The morbid jokes, the really grotesque, foldy, chunky characters…that’s so good.

Edward Gorey, too. Anything morbid, I was attracted to. Morbid crosshatching was a frequent obsession of mine. I got Amphigorey[7] when I was a kid, and I read that over and over and over again. The Gashlycrumb Tinies.[8] They all die in horrible ways and their children. And Gorey was probably some sort of queer, but we don’t know. Actually, that’s one of my big ‘HRT-could-have-saved’ right now.

We talked about Allison Bechdel before. I really like Allison Bechdel. It’s funny that people just know her from the test,[9] because she’s actually a top 5 living comics author. She’s really good. She’s a master of the medium. I was looking at old Dykes to Watch Out For the other day, and they’re gorgeous looking. There’s a great mastery of li ae and form. Once again, chunky. I love how chunky her characters look, how, like, three-dimensional they end up looking as a result of her cross-hatching. I can’t paint worth a lick, I can’t do any painting, but I’m very inspired by a lot of painters. I read a lot of Mad magazine when I was a kid. I even have my Mad magazine 9-11 issue right there. It’s one of my prized possessions. My favorite 90s Mad artist was a fella, Hermann Mejía. He’s kind of obscure but he had this quality to his painting, which I call, the paper bag quality, where his stuff would look almost polygonal, but still that meat or heft to it.

Swamp Thing by Phil Hale

Swamp Thing by Phil HaleAnother artist like that is Phil Hale, the fantasy illustrator. He also has this chunky paper bag quality to his work, and I find that stuff irresistible. If I could paint, I would want to paint like that. And I try to render my crosshatching stuff with that type of texture or quality in mind.

Other people…George Herriman, God I love Krazy Kat.

McFadden: Who are you reading now?

Hood: I inherited a bunch of old Creepys from my dad. He went Catholic, and he was like, ‘these are all infected by the devil, do you want this collection of old [Creepys]?’ and I said, ‘fuck yeah, give me your old Creepy comics.

If I could draw like anyone, I would draw like Wally Wood. I’m not a hyper-technically gifted artist. I composed a lot of stuff together, and I’m very self-taught, but I’ve got a shaky hand. But those old 50s compositions of someone like Milton Caniff and Alex Toth, and fucking Wally Wood, and John Severin. Those are the guys. Those are fucking comics.

All these Creepys look so good. People are always asking ‘why do manga comics always outsell Western comics. What’s the deal there?’ I think one of the facts is that, because of the expectations for everything to be hyper-gradient and have that realistic coloring style, in the similar way that film has that gray verisimilitude thing—that Russo Brothers verisimilitude. It resulted in [comics] being, like, way less legible, because there’s no contrast between dark and light in the way that there are in old comics. There’s no bands of color with which to delineate background and foreground more easily, so you end up with compositions that are cluttered where your eye is not drawn to anything specifically.

And that’s because the coloring, by virtue of its realism, ends up making it sort of flat and too detailed to really pay attention to. You just read an old Kirby comic, where the background is a color. And it’s like, ‘oh, these are so much easier to read I’m not struggling to, like, drag my eye across the page.’

People tell me, ‘get into Chainsaw Man, you’ll love Chainsaw Man.’ I’m sure I would. I see the compositions of that guy [Tatsuki Fujimoto], and they’re legible. One, because it’s in black and white, and two, because it has contrast between blacks… It’s why Mignola compositions are so arresting because he makes a part of the frame really dark. People knew this in movies a while ago, and then they forgot it for some reason. They forgot that the frame needs to be split up into two bands of color. And that will determine the way that your objects are oriented. That’s what I’m talking about with George Herriman, too. Coconino County is a perfect articulation of comics composition, because it’s just a horizon, right? And the frame is dictated, just like in the Fablemans. If the horizon is at the bottom or at the top, it’s interesting. If it’s in the middle, it’s boring as shit. Coconino County would always be separated by that foreground, by that light and dark, or just even the line in the middle representing the horizon being that band of dark that delineates characters in space.

That sense of composition has been lost. It’s why, uh, manga hasn’t lost that to some degree. They still have that sort of cinematic compositional identity, or the classically cinematic compositional identity.

McFadden: What’s your process like? What are your steps for drawing a strip?

Hood: Every day, I’m just naturally thinking of jokes, which is why I do this. I’ll be in the shower and I’ll have an idea or a phrase will come up into my head like ‘I haven’t made a basketball joke. What’s funny about basketball?’

It used to be that the process was much simpler, because, in the early days of the comic, the idea was to just make a lot, so much, so many comics it was bewildering. And I had one joke, basically, which is, ‘what if Dick was X?’ And that fueled, like, 800 comics, and you see less of the dick comics, because I burnt out on that joke. You draw 800 of those, and it’s like, ‘okay, I think I’ve done most conceivable variations of this. I’ve gotta move on. What about relationships?’

That was the process of coming up with ‘what if Dick was xylophone.’ Now I’ll be thinking of something funny, or I’ll get an idea in my head, or something will happen to me in real life. The other day I was out with stubble, but still dressing in my booty shorts, which is a look calculated to drive a certain type of person insane. I was walking past, and somebody called me an abomination. I was like, ‘wow! That’s… that’s old school,’ And I’ve been trying to think of a funny angle to this. How do I make a joke out of someone calling me an abomination?

McFadden: Is your stuff digital, or is it paper?

Hood: It’s all on paper. I also encourage people to draw it on real paper, because I make a decent chunk of my income that way because I got to the point where I can charge $125 per original drawing, and sell 25 of them a month. And I have a backlog of literally 1,800 of them so it’s a very consistent and reliable way to get [paid] and also to sell stuff that I believe in. Here’s a piece of original art that could stand to be of value if I get more famous or, you know, do something weird. So I do see a value in that, otherwise they’d just be rotting in a box in my fucking house. That’s why I encourage physical media as well, because it’s something you can set. It’s like an NFT, but in real life. There’s an original piece of art, and it’s valued by virtue of being the original.

I do it through Big Cartel, whenever I just need to scrounge up funds. That’s easier said than done, because I was grinding out free shit for a couple of years before I got the type of notoriety that would make people want to buy my stuff like that. But once you’ve ground it out for two years, suddenly you have this backlog of shit that you can sell. So, it’s this accumulatory[sic.] process.

McFadden: Are comics your main job now?

Hood: Yeah. This is what I do. Between Patreon and selling original art and commissions, I can live wretchedly. But that’s so much better than office, holy shit, you know, this was the dream. Piecing together a life where I don’t have another adult correcting my grammar even if they were right, I couldn’t take that anymore. I’m very lucky.

I’m probably gonna relent and try to get some sort of literary agent soon. I’ve been trying to coast on this without doing fully DIY for a while now, just because it feels weird to try and incorporate oneself and pursue something on that level. This started out as hobbyism, and suddenly, I became a professional. And I didn’t notice it happening

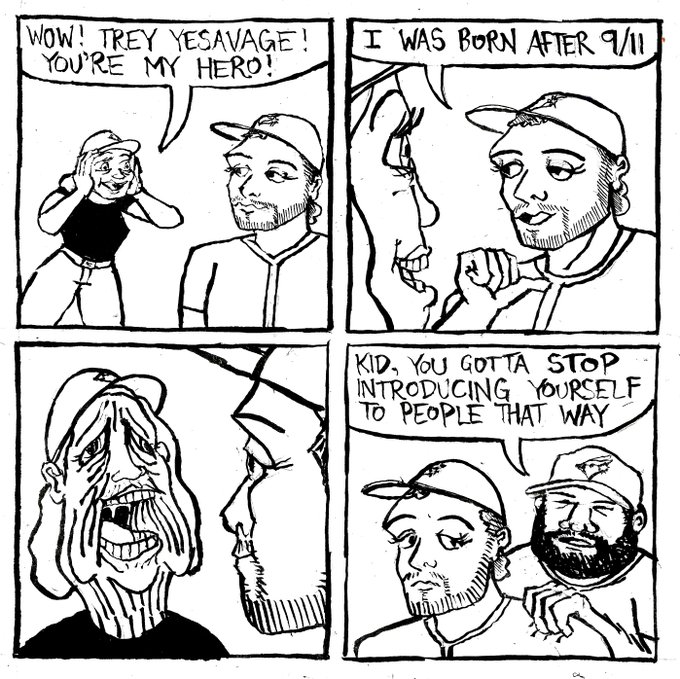

I went to TCAF [Toronto Comics Art Festival] this year. The other thing about being e-famous is that I love it when people come up to me, and they’re very effusive about the comics. Young people who it becomes apparent you have thrall over. And they think you hung the fucking moon. So then there becomes this immediate task to say ‘kid, I am an idiot. Please don’t look at me like that.’

I shouldn’t reject that as much. I did a show recently, a live show with poetry and my band. And someone was talking to me, and she was in tears, about my book. It’s very intense, and I loved it. Honestly, I’m glad. In fact, that’s the goal, right? To affect someone that much. But it also is very…wow. You could probably do something like this. There is that sense of at once joy that your stuff is reaching people, but this sense of mortification that you have somehow played an important role in someone’s life without realizing it. I’m getting used to it. The fear I have is that I’ll get used to it, and I’ll see it as a given that I’m beloved, when no one should get used to that idea. That’s not a normal thing.

You should be liked in that way because you have an intimate relationship with somebody that you’ve worked at for many years. I also think the reason why I’ve pulled back from social media, or feel guilty about the selfies is because we traffic in e-celebrity, this is the way that you put your art out there. So, I made this conscious decision that I’m gonna be the thing that is commented on and not the commenter, in order to hawk my wares. I’m going to be the source of discussion, and that was a bad idea. It’s good because it allowed me to live off of my art. It served that means to an end. But now I’m here and I find myself having done something that I think people probably shouldn’t do, which is pursue that sort of small fame celebrity thing on the internet. I think that’s a problem, which is easy for me to say, because it worked out okay for me. But it’s made life weird. in ways that you can’t anticipate, and ways that I don’t want to downplay, because it makes interaction strange. If you do do it, keep your real persona as separate as possible from your internet persona, which is something that I didn’t do either.

McFadden: What’s your dream project? If someone reached out and said ‘here’s a bunch of money, do whatever you want.’ What would that look like?

Hood: What’s great with comics is you don’t need a bunch of money to do your dream project, you just need time. I really want to make a movie, but I’m so cranked that I hate spending money at all. So the idea is a movie that’s not something like Derek Jarman’s Blue that can be made on the cheap. I haven’t figured out the clever puzzle of how to do my ultra-low-budget feature length yet.

But my dream project is whatever the next one is. I’ve had a lot of movie ideas tossed around in my head. I want to do a neo-noir…things in this genre, things that really expose the psychogeography of Toronto as well, because I see no movies about Toronto. We got Atom Egoyan and [David] Cronenberg and stuff like that, but I want more. There’s so many movies about Chicago, and New York, and, you know, even where you are in Oakland, there’s movies that explore the geography and the unique qualities of that city.

I think in terms of the next comic project, which is something that I want to get on, I’ve had this harebrained idea for a Mission Hill fan comic where Kevin turns out to be trans. And I’m writing my own Mission Hill storyboard, essentially, because I love that show so much, and it’s always in development hell in terms of getting a Gus and Wally reboot.

I love the character design so much, and I have so many jokes that are already obvious to me in my head. Maybe getting the attention of [Bill] Oakley and [Josh] Weinstein[10] senpai who’ve interacted with me before because they’re online. Honestly, it’s a big deal. I wish it weren’t as big of a deal when my cis heroes were people that accept me. But when Charles Barkley said, ‘trans people, you’re all right,’ I fucking cried! That shit was really important to me for some reason. I don’t know why. I loved him as a kid so much, and it meant a lot to me that he said that. So, there is this desire to get Bill Oakley and Josh Weinstein to be like, ‘trans rights!’ and make a comic of quality. Get some Simpsons writers on board. So look out for that in the future. That might be coming sooner than you think.

McFadden: A lot of indie cartoonists are being handed the reins to the classic newspaper strips, for instance Caroline Cash is doing Nancy now. What strip would you want to take over?

Hood: If I were to get the reins of, like, a classic, [I’d choose] Dilbert. I would want to write my trans Dilbert. Can you imagine, like, writing Dilbert and then it going to your head that that much.

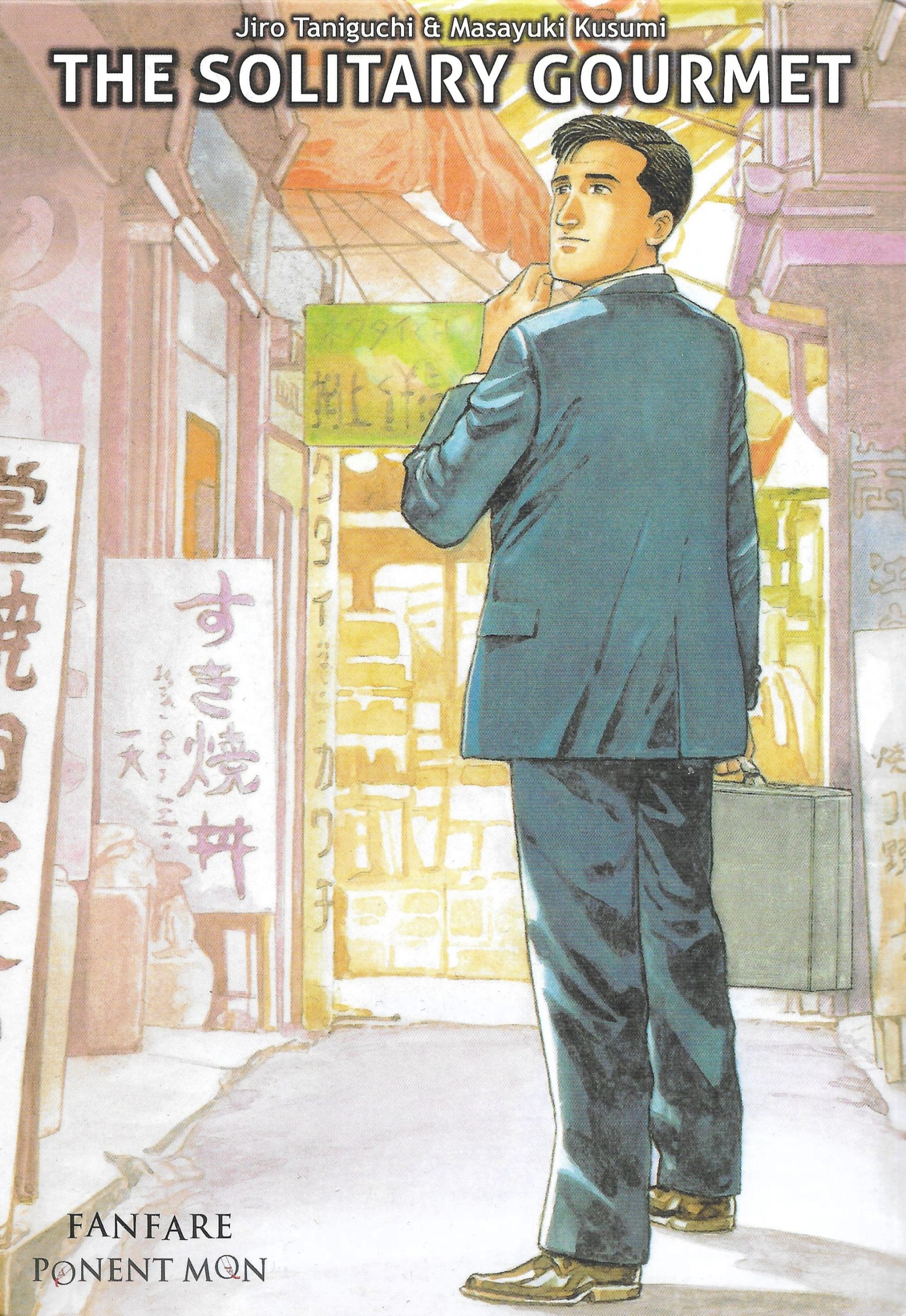

Lynn Johnston’s For Better or Worse

Lynn Johnston’s For Better or WorseI’d love For Better or For Worse, but I wouldn’t want to revive it. It’s perfect as it is, and needs to stay that way. It would have to be something that takes more to revive, something that has a rebootable quality. Whereas, For Better or For Worse was too diaristic

Honestly it would be awesome to get Garfield. If I could get Garfield and get weird with it, that would be fucking cool.

God, if I could do Krazy Kat, that would be my dream. If the Herriman Foundation is like, ‘You! You seem like a good opportunity’, and for some reason, newspapers have decided to give you gigantic blocks, like they did to George Herriman back in the day. Obviously that would be untannable now, because Krazy Kat depends on the fact that it had such space to work with.

The Onion‘s recent success with print media, where it offers basically a to-order subscription service as opposed to printing a lot, and then making its money through advertising, where the thing that you’re paying for is the print, as opposed to the ads as a new model for print media is actually pretty useful.

Obviously the market’s gonna be way smaller, but there is a big enough market for people that value physical media and collecting physical media, especially because the internet has created a market for that as well. People are so unenamored with the fact that everything is easy.

It’s dead internet theory. Websites fall away, they disappear. That promise of permanence on the internet was not founded. So I think people are rediscovering the value of physical media, and I see a way forward for that. Your max subscription base will be something like 20K, but that’s still enough for a small publishing house, right?

I’m not gonna be the one to do that. You need a person who’s good at logistics and unfortunately, sourcing a logistics person in the comics industry is like being a service top, you’re cleaning up, baby, in the trans community. So if you’re a person that knows distribution and just how to source newsprint and how to print it expediently, please find us helpless morons, because I need your help, all I do is draw, the only thing I know how to do is cartoons.

McFadden: If you had to pick three cartoonists living or dead that you think everyone should read, who would they be?

Hood: I’m gonna give some, like, basic-ass answers, but like I said before I’m not particularly well-read. I’ll start with the stuff that really influenced me, and that made me want to make comics that I think of as little sparks in my head.

Everyone says Alan Moore, you love Alan Moore, Alan Moore is the best, Grant Morrison is this sort of Erzatz version of Alan Moore, but here’s the thing about Alan Moore. Alan Moore did not write queer characters, ever—almost ever. But the first ever empowering representation of a trans woman I ever saw was Lord Fanny in The Invisibles. I love the Invisibles, and Grant Morrison is not a cartoonist, they’re a writer. So that’s not even an answer. But I love Grant Morrison. Invisibles is a big, long fucking anthology, but the other Morrison that I read around that time, which is a little easier and also incorporates an artist who’s one of my guys is Bill Sienkiewicz who did Arkham: A Serious House on Serious Earth. I love that book so fucking much. Because Arkham is this id-like fantasy. This vignette-like exploration of a subconscious. And that’s my favorite type of shit, this disconnected nightmare that wouldn’t work if it didn’t have that Sienkiewicz art. It also has my favorite conception of the Joker in it, where Joker is super sanity. He’s not insane, it’s just that he adjusts himself every day to the new reality of life, which is because Grant Morrison was obsessed with unifying all the Batman timelines, so how can Joker be like a Cesar Romero type guy, a jokey guy, but also beating Robin to death with a pipe, and that’s because he’s a different guy every day. And I always like that idea. Sienkiewicz’s stuff is marvelous. The entire breadth of it has that heft and that grit, and that reality, but emotion. The sort of hyper-realism guy like Alex Ross, who I love, because of the formality of the work, it lacks that expressionistic quality that Sienkiewicz has.

Pogo by Walt Kelly

Pogo by Walt KellyI think everyone should read Pogo. Here’s the thing about Pogo. They are not fun to read. It’s not like… I don’t think Pogo is necessarily good. But it’s really historically important, and Walt Kelly’s art I’m surprised I don’t meet more furries who are Pogo heads, because it’s like the ur-furry art. Furry art is this massive sect of comic art. More massive than we’re willing to admit, because there’s still some sort of weird Puritanism about them. But right from the very beginning you have characters whose ideas are better expressed through the innocence of anthropomorphized animals interacting, right? I love it. I think it’s very charming. It’s a hard pitch. They’re always talking in weird accents that are spelled and the jokes aren’t funny. You very much need that sense of 50s ‘things are just happening, and they’re just saying anything right now.’ I see [Walt Kelly] ignored a lot in terms of the historical pantheon of cartoons, and I would like to draw people’s attention more to Pogo as a piece, because from Pogo springs Omaha the Cat Dancer. Even in non-furry stuff, like Love and Rockets, where the simplicity of the characters is contrasted with their real adult problems through their real dialogue, and their lived-in character representations. I think Pogo influences a lot of that surreptitiously without people noticing it. So I’d like to see a return to Pogo scholarship. Not even just that, but talk about autobio and the way that the characters spoke in [Pogo} was so naturalistic.

Honestly, I mentioned her before, but Lynn fucking Johnston. I think For Better of For Worse is due for a re-evaluation in terms of how significant of a work it is. People were impressed with Boyhood, or people are impressed with Dave Sim for that upkeep, but this is a lady who did a consistent story for 25 years. She was talking about gay rights before anybody else. She killed a fucking dog!

![Ghost of Yōtei First Impressions [Spoiler Free]](https://attackongeek.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Ghost-of-Yotei.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·