Hank Kennedy | August 21, 2025

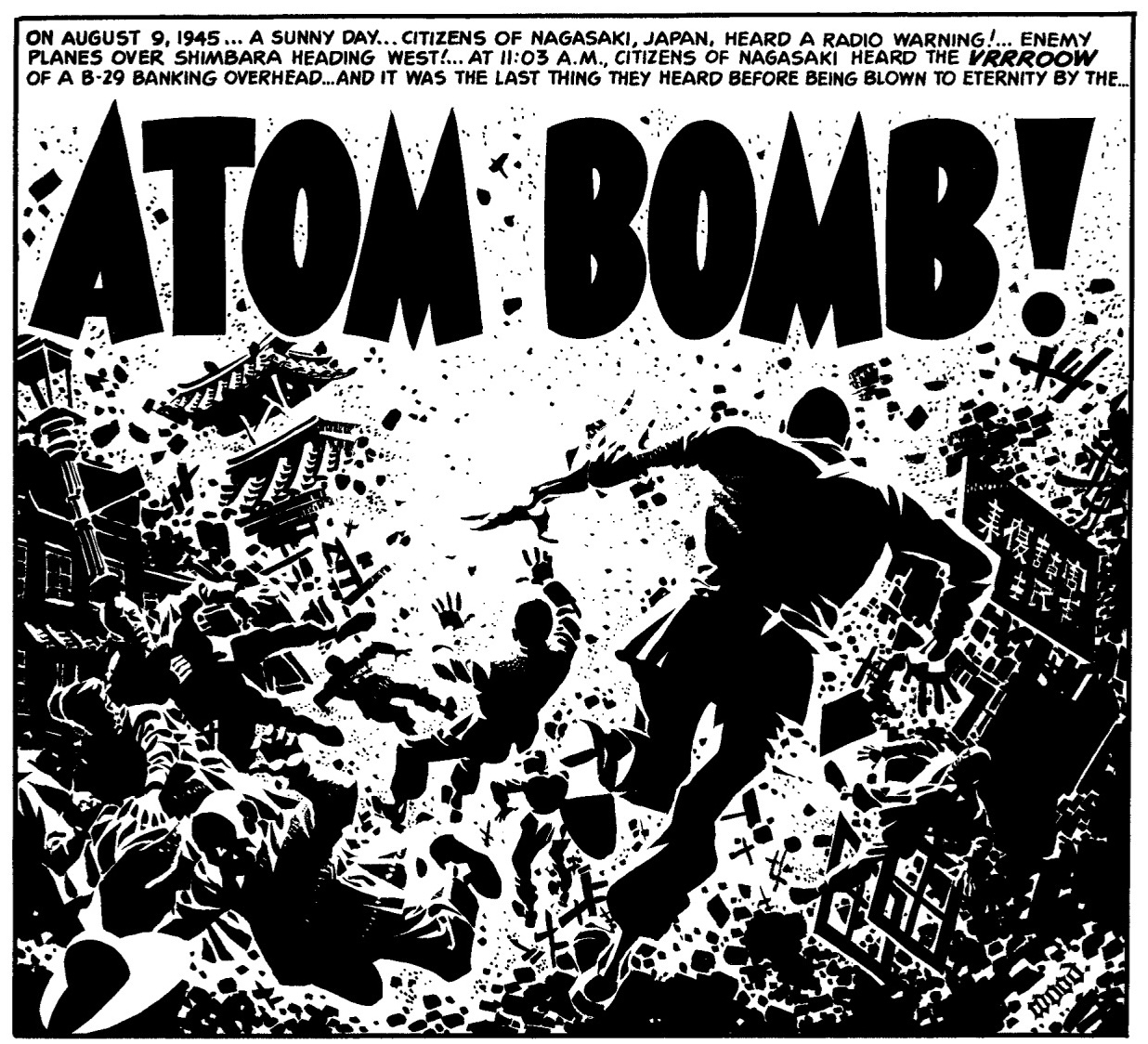

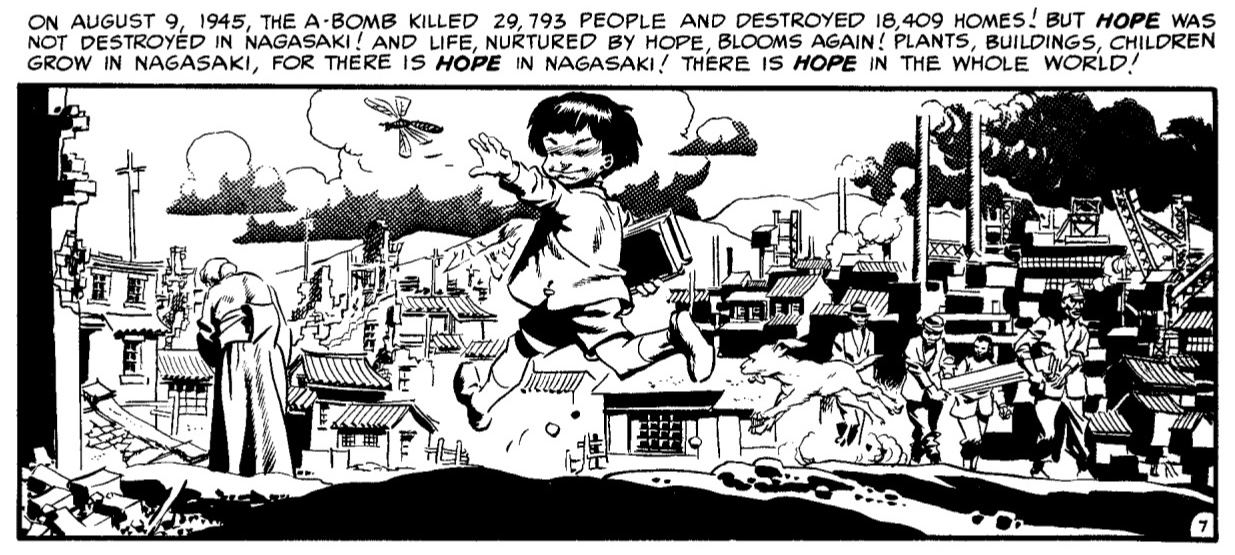

Title panel to "Atom Bomb" by Harvey Kurtzman and Wally Wood. Taken from the Fantagraphics collection Atom Bomb and Other Stories.

Title panel to "Atom Bomb" by Harvey Kurtzman and Wally Wood. Taken from the Fantagraphics collection Atom Bomb and Other Stories.“Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Moscow, too,

New York, London, Timbuktu,

Shanghai, Paris, up the flue,

Hiroshima, Nagasaki.

We must choose between

The brotherhood of man or smithereens.

The people of the world must pick out a thesis:

‘Peace in the world, or the world in pieces!’”

—Vern Partlow, “Old Man Atom”

In the aftermath of the atomic bombings of Japan (the 80th anniversary of which just passed), American popular culture had two responses, broadly speaking. The first was to warn of the dangers inherent in the new weapon; to world peace, to civilization, or even to the human species. The second was a call to stiffen the nation’s spine, and be ready, able, and willing to use the bomb against Godless, atheistic, monolithic Communism.

The first response could be seen in films like The Day the Earth Stood Still and Them! Aliens from outer space took time to threaten humanity to give up our nuclear weapons. Giant ants resulted from reckless nuclear testing. If the bomb didn’t get us, irradiated mutants would.

The second was showcased in 1952’s low budget Invasion USA and the 1947 MGM film The Beginning or the End, produced with the help of the U.S. government. Containing several distortions of fact, this was the version of history the establishment wanted people to believe. The film showed President Truman agonizing over the bomb, when in truth he boasted over how easy the decision was, and falsely showed Japan was about to complete its own nuclear weapon. An Enola Gay crew member remarks “We’ve been dropping warning leaflets on them for ten days now,” referring to the people of Hiroshima. No such explicit warnings were given. Reviewing the film for the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, Harrison Brown described that sequence as “the most horrible falsification of history.”

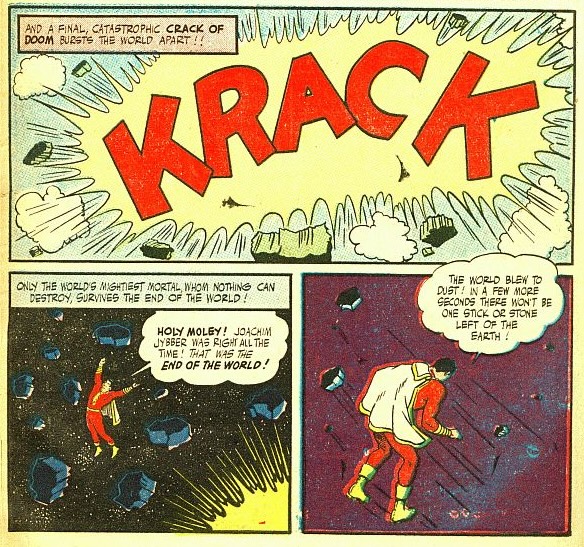

Sequence from Captain Marvel Adventures #71.

Sequence from Captain Marvel Adventures #71.Criticism of the decision to drop the bomb came from Christian publications like the Christian Century and Commonweal. The former warned in 1945, “Our future security is menaced by our own act.” That same year, the latter argued, “The name Hiroshima, the name Nagasaki, are names for American guilt and shame …” Left-wing critic Dwight Macdonald wrote in his journal Politics that such “atrocities as The Bomb and the Nazi death camps are right now brutalizing, warping, [and] deadening the human beings who are expected to change the world for the better.”

Military leaders also made their misgivings public. General Eisenhower stated in his 1948 memoirs he “disliked seeing the United States take the lead in introducing into war something as horrible and destructive as this new weapon.” Presidents Roosevelt and Truman’s chief of staff Admiral William D. Leahy wrote in his own 1950 memoir that “in being the first to use it, [the United States] had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages." The U.S. military’s own Strategic Bombing Survey concluded, “Certainly prior to 31 December 1945, in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered, even if the atom bombs had not been dropped, even if [the Soviet Union] had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.”

Comics made their own responses to the bomb. At first, most showcased the fear and apprehension that developed in the shadow of the mushroom cloud. Captain Marvel Adventures No. 71 contained “End of the World.” Here, an Asian mad scientist builds a Proton bomb, a super-powerful atomic weapon strong enough to destroy the world. Captain Marvel fails to prevent him from detonating it and the world is obliterated. Fortunately, the hero had been on a parallel Earth and his own planet survived ... for now. In Wonder Woman No. 44, the superheroine battled Master De Stroyer, a criminal who has stolen enough nuclear weapons to blackmail the world. When he is annihilated by his own bombs, Wonder Woman comments, “Those who live by violence are more than likely to meet a violent end!”

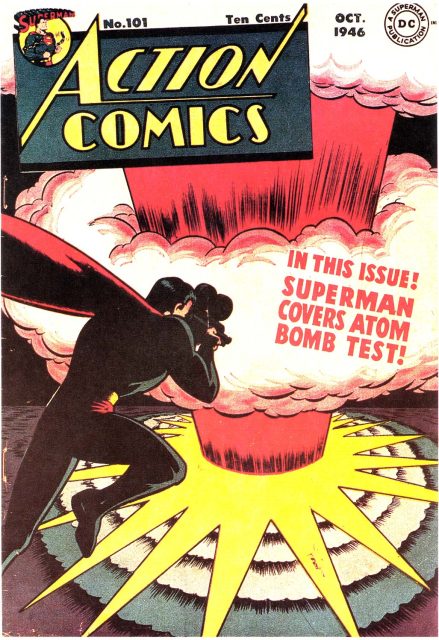

Cover to Action Comics #101

Cover to Action Comics #101The Last Son of Krypton was an exception to this general trend. Action Comics No. 101 from October 1946 performed two important functions. First, it assured skeptical readers that the Man of Tomorrow could survive an atomic explosion. Second, it signed Superman up for the Cold War. Superman offers to photograph the Operation Crossroads atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll. “The photos will be a warning to men who talk against peace,” Superman proclaims.

After the Soviets developed their own atomic bomb in 1949, and even more so after the Korean War began, comic messages like these dropped away. In the nation’s editorial pages, the cartoonist Herblock halted drawing cartoons on the menace of the atomic bomb for fear his work would be “mixed up with a carefully twisted viewpoint” expressed by “Communists [who] were plugging their” own opposition to U.S. policy. Instead, comics appeared that argued for a nuclear high noon showdown that would end the Cold War.

A comic that reassured the capitalist West that nuclear war was not only survivable, but winnable was Atom-Age Combat from St. John Publications. The short-lived series followed Buck Vinson and his “Atlantic Police Commandos” in their struggle against “the ruthless Red Asians.”. Despite the presence of atomic machine guns, atomic rifles, atomic artillery, and atomic grenades, these weapons are seemingly no more dangerous than their non-radioactive counterparts.

In Atom-Age Combat 3, Air Marshal Boris “The Butcher” Kasilov battles the heroes in an African jungle. “Take cover, he’s going to toss a hydrogen grenade,” Vinson yells to his comrade. Fortunately, “a massive tree trunk shielded the pair from the radioactive blast.” Kasilov himself is no worse for wear after the grenade goes off. Another title, Youthful Magazines’ Atomic Attack, also blithely introduced a host of atomic weapons. These were about as effective as the armaments in Atom-Age Combat. Atom-Age combat, comic book-style, was little different from what came before. Call it a kinder, gentler, atomic holocaust.

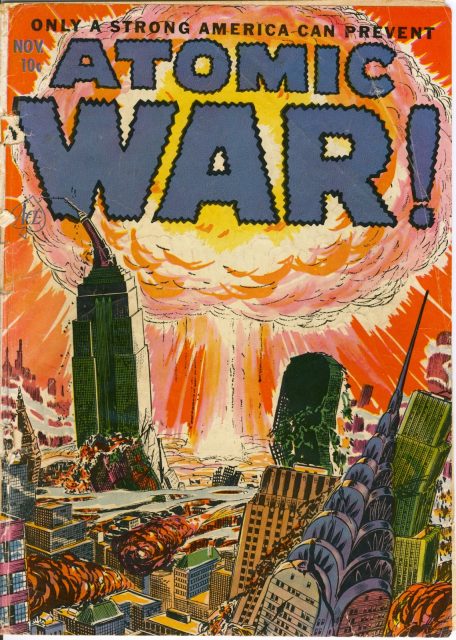

Cover to Atomic War #1.

Cover to Atomic War #1.Ace Publications followed up their World War III tale “The War That Will Never Happen, if America Remains Strong and Alert” with Atomic War! The title exhibited doublethink that would make the Party in 1984 proud. Text in the comic stated it was meant to illustrate “the utter devastation that another war will bring to all, the just was well as the unjust.” The first issue concludes with this declaration: “This magazine was meant to shock you — to wake up Americans to the dangers, the horror and utter futility of WAR!”

Nevertheless, readers are shown that the Soviets cannot be trusted, that “only a strong America" can prevent World War III, and that those looking for arms control talks or negotiations are merely taking up the part of Neville Chamberlain from the previous global conflagration. Nuclear weapons are shown as a viable means of waging war. One story concludes with a U.S. pilot returning from dropping a nuclear bomb on Moscow, beaming “We’ve changed the map of Russia!”

Captain Marvel comics continued their earlier skepticism of the Bomb. In Whiz Comics No. 150, the Captain travels to South America to halt a nuclear war between super-intelligent wasps and ants. To head off future wars, the two species create United Insects. Captain Marvel reassures the arthropods, “Like our United Nations it will promote peace here in your insect civilization.”

But it was EC Comics that really took up the challenge of frightening readers about the dangers of the nuclear arms race. Weird Fantasy No. 11’s “The 10th at Noon” depicts the well worn fantasy premise of a camera that takes pictures of the future. In the concluding twist, a photograph is taken of New York City. The photo shows the metropolis devastated after a nuclear attack. In Weird Science No. 12, “The Last Man” shows a survivor of World War III seeking out a woman with which to repopulate the world. When he finds her, it is his own sister. Rats inherit the Earth after human beings wipe each other out in a nuclear exchange in Shock Suspenstories No. 8’s “The Arrival.”

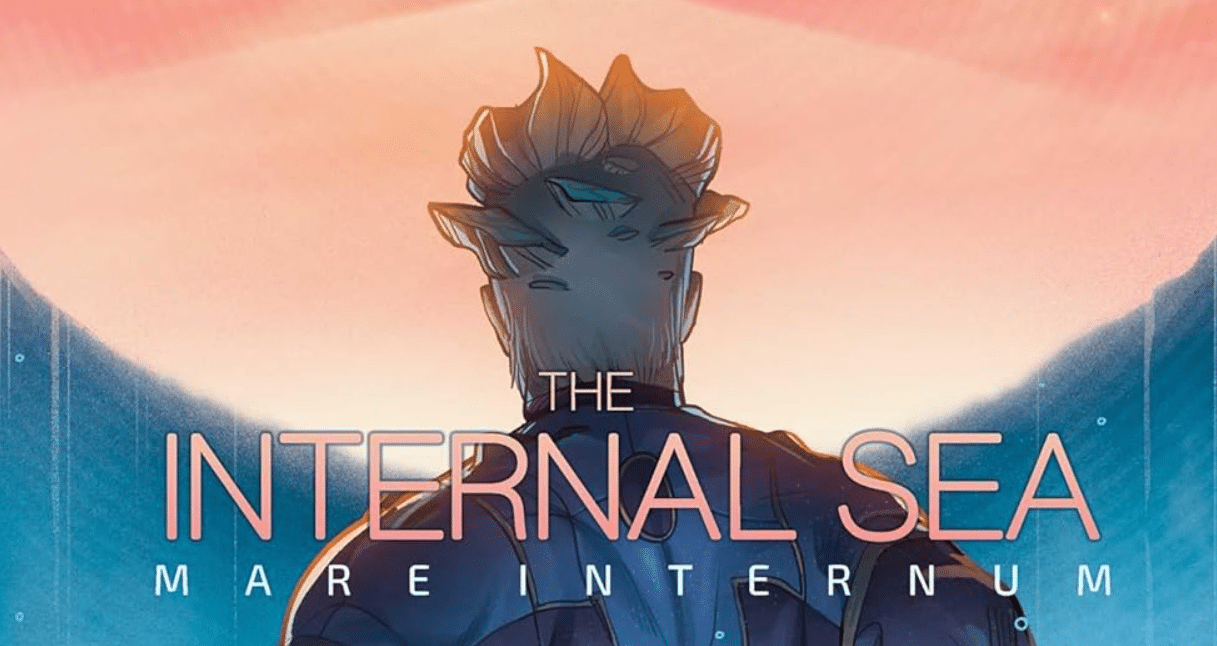

Unlike the science-fiction offerings, Harvey Kurtzman looked back at the recent past. “Atom Bomb,” written by Kurtzman and drawn by Wallace Wood, recounted the bombing of Nagasaki from the Japanese perspective. The comic works as a companion piece to John Hersey’s Hiroshima. That nonfiction book detailed the horrors of the bombing in Hersey’s clear, precise prose — the eyeballs melted, the people vaporized into shadows on a wall. Methodist Minister Kiyoshi Tanimoto attempted to rescue people lying on a riverbank. “They did not move and he realized that they were too weak to lift themselves. He reached down and took a woman by the hands, but her skin slipped off in huge, glovelike pieces. He was so sickened by this that he had to sit down for a moment. … He had to keep consciously repeating to himself, ‘These are human beings.’”

Sequence from "Atom Bomb."

Sequence from "Atom Bomb."Despite the general EC reputation for gore, the comic does not recreate images like these. Instead it creates horror by following members of the same family going about their day-to-day lives before “they were blown to eternity” by the bombing. Two children are shown killed, a boy in the blast itself, a girl slowly via radiation poisoning as she “coughs and spits blood.” When the father of the two, a POW in Siberia, gets a letter with news of his dead children, he dies of grief on the spot.

Yet “Atom Bomb” ends on a note of almost manic optimism. One of the POW’s sons has survived, to be raised by his grandmother. Because of this, the concluding narration informs readers that “hope was not destroyed in Nagasaki! And life, nurtured by hope, blooms again! Plants, buildings, children, grow, for there is hope in Nagasaki! There is hope in the whole world!” In part, the hope of “Atom Bomb” comes from its vast undercount of the dead. Kurtzman writes that 29,973 were killed. In truth, the number is between 60,000 and 80,000. Kurtzman once admitted that his anti-war stories were too “subtle by comic book standards.” The U-Turn ending of “Atom Bomb” provides some evidence for that view and Two-Fisted Tales printed no responses to “Atom Bomb,” so what readers made of the story remains a mystery.

From "Atom Bomb."

From "Atom Bomb."In the decades that followed, nuclear weapons remained a part of comic books, as they were a part of culture at large. In the late '50s, Mad offered a parody “Hit Parade” of post-apocalyptic ditties that “young lovers of future generations will be singing as they walk down moonlit lanes arm in arm in arm in arm …” Marvel’s the Hulk was born out of a Gamma bomb test. In Japan, the manga Barefoot Gen and I Saw It showcased the Japanese point of view of the bombings. Nonfiction comics Bomb, the Bomb, Fallout, and Trinity have all retold the story of the Manhattan Project and the decision to use “the gadget” on Japan.

For the fortieth anniversary of the bombings, historian Gar Alperovitz wrote in his The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb and the Architecture of an American Myth, “To be silent about the past is to accept the decision silently, with no challenge. It is thereby also to sustain and silently nurture the idea that nuclear weapons can and should be used or threatened to be used.” Comics have heeded Alperovitz and refused to be silent about the history of nuclear weapons or the threat they pose to human survival.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·