Tom Shapira | August 28, 2025

“[Munsky and McClure] were now selling magazines bellow the cost of production. They were able to do so because the big money came from selling advertising. Ads in turn were an artifact of the boom in mass-produced consumer goods” — Mike Wallace, Greater Gotham: A History of New York City from 1898 to 1919

Do you want to know how the sausage is made? Not me (I don’t even like eating them). I do, however, want to know how comics are made, and have read many a history and theory books about the subject. After all, comics aren’t hot dogs. Or are they?

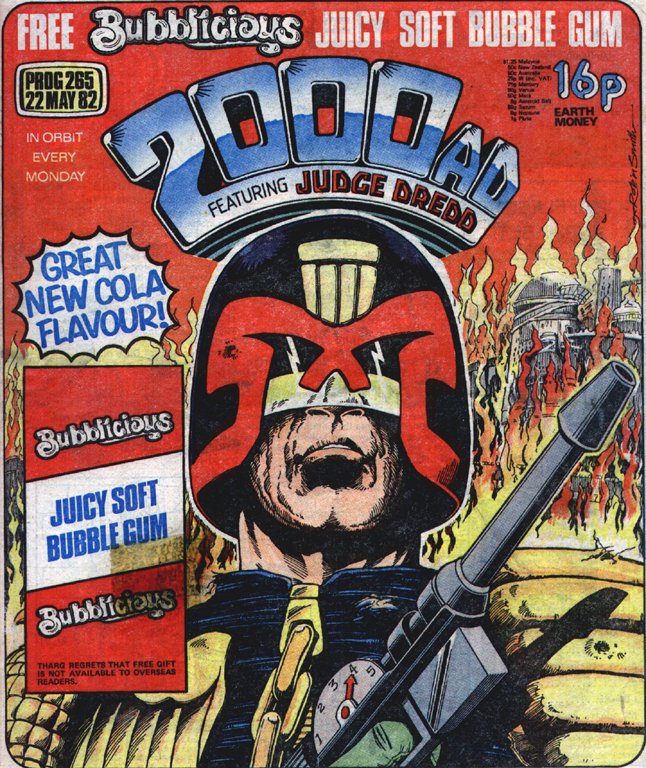

That is the main question to ponder while reading through Cover Story, half an art book and half rumination on working in commercial comics, written by artist Robin Smith (he of The Bogie Man fame). Smith is mostly familiar as a comics artist in the British industry, a Judge Dredd story here, a Time Twisters one-off there, but a large chunk of his work was behind the scene as art editor for 2000 AD. Which means doing cover design. This book presents the (until now unknown) fruits of his labor. Every double spread of Cover Story includes the finished cover, starting with prog #193 (January 1981) and ending with 2000 AD Annual 1987 (September 1986), alongside Smith’s original cover sketch (including the notes to the cover artist) and about half a page of text to accompany the images. These texts might include the actual artistic influence on the covers (a shot featuring the heroes caught in a searchlight was inspired by a late night encounter with a burglar), but mostly are just generic praise words. You wouldn’t be surprised to know that Smith thinks Carlos Ezquerra is a good artist, that Ron Smith is a very good artist, that Mick McMahon is a great artist etc. .

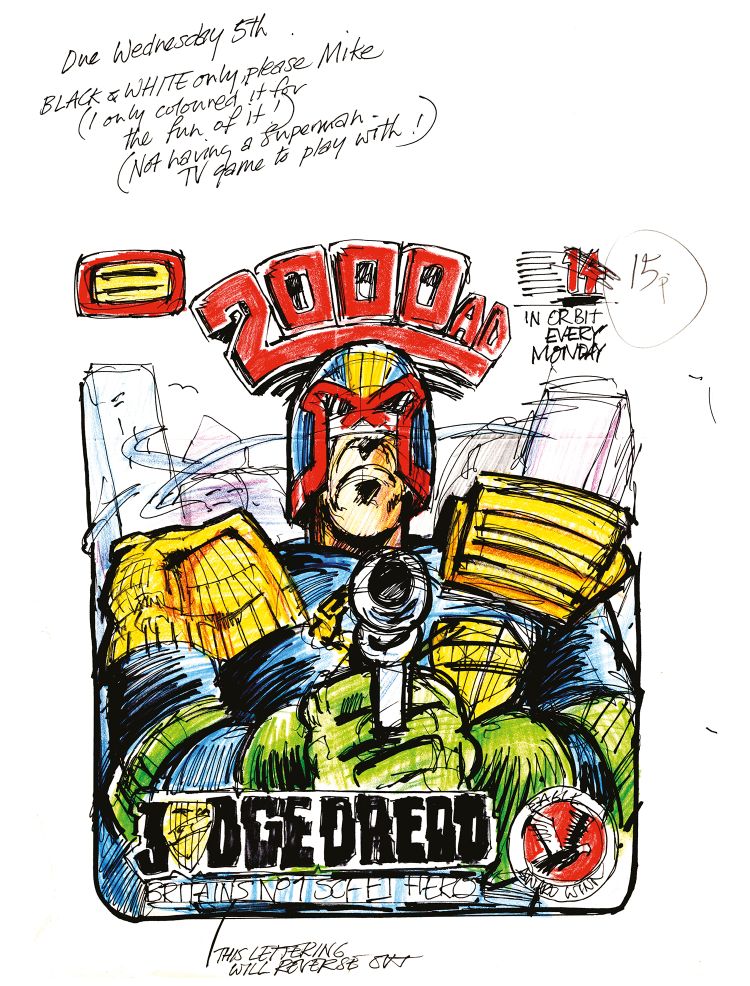

Robin Smith's process version

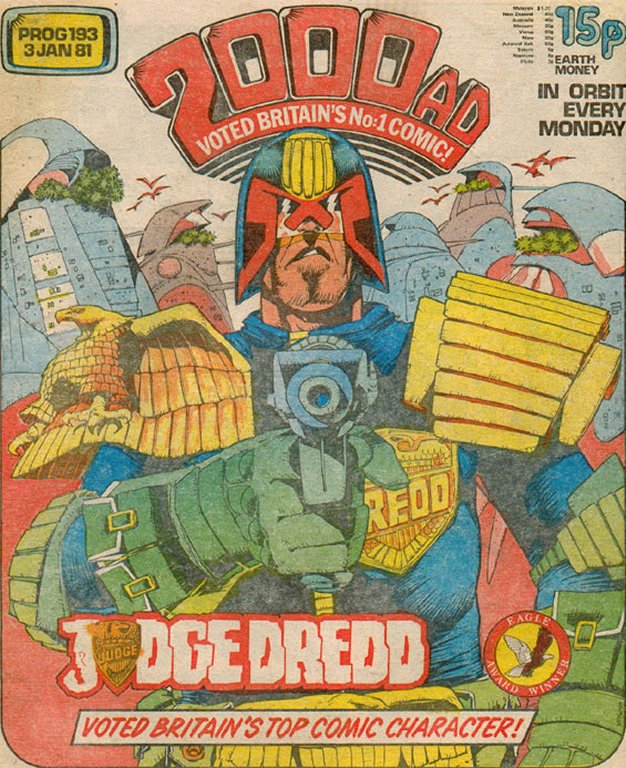

Robin Smith's process version Mick McMahon's published version.

Mick McMahon's published version.As a piece of comics history it’s a far cry from Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, as an exploration of the process of comics creation it’s not really in the league of How to Read Nancy. It’s a bit too nice, too close to the people involved with too little space to actually explore its subject in depth. Still, there is value to be found in Cover Story. If nothing else it shows how much is done behind the scenes: Smith’s cover sketches aren’t just a rough notion of an idea, they are often extremely close to the finished object; to such a degree that makes you wonder why he isn’t credited.

His sketch for prog #338, with Judges Dredd and Hershey breaking into an apartment of two random citizens on a "crime swoop," was near faithfully adapted by Ron Smith. In the finished cover Hershey’s pose is slightly different (hunched instead of standing ramrod straight), the surprised citizens are a couple of decades younger and the apartment has a slightly more 20th century sense to it. It seems like they could have saved a lot of effort by simply going with Robin Smith’s version (I prefer his take, with the glasses comically popping off the surprised citizen’s face). One could argue back and forth about the superiority of each cover — Smith seems to have an overall better sense of the interaction of the drawing with the textual elements, but no matter which version you choose one cannot deny his presence.

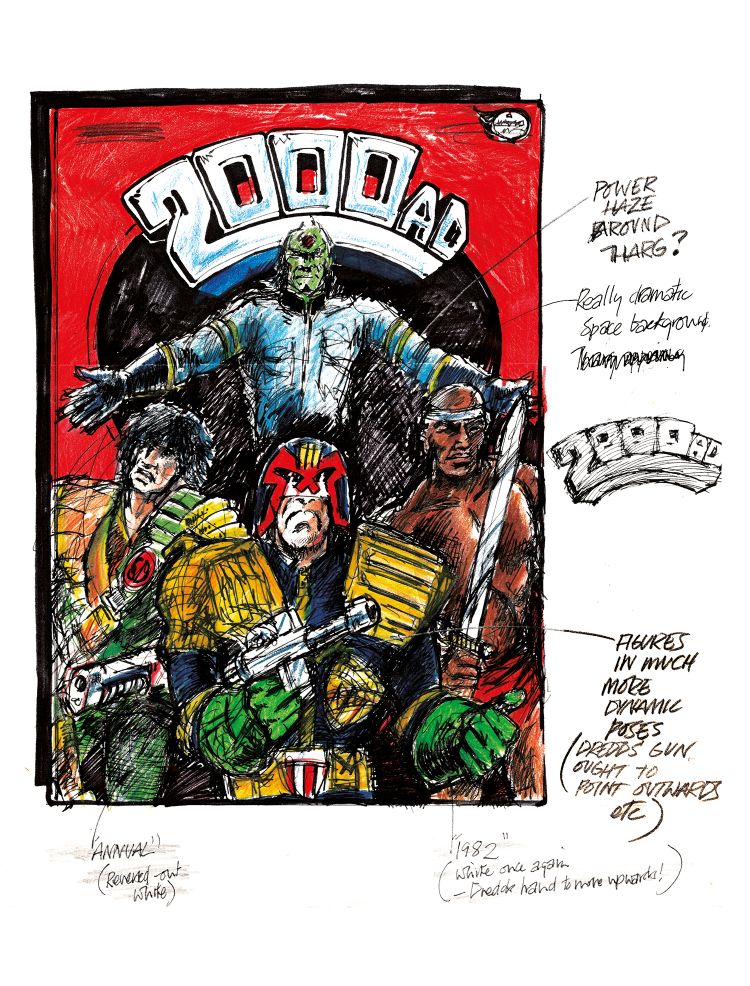

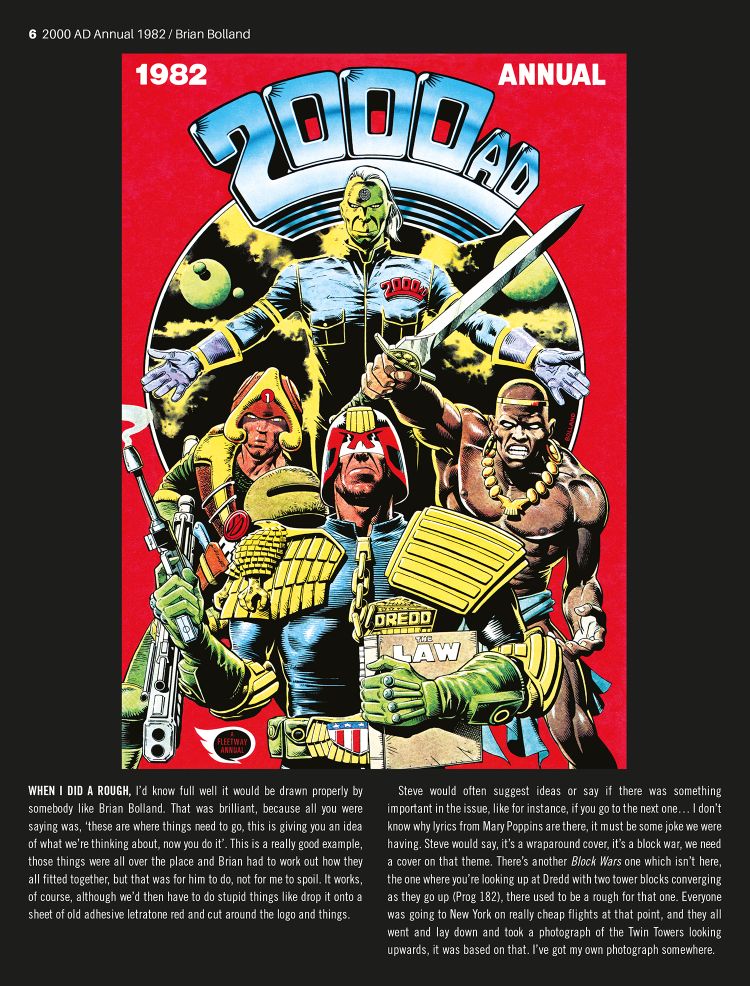

Robin Smith's version of 2000 AD Annual 1982

Robin Smith's version of 2000 AD Annual 1982Leafing through this book is a good chance to gain new appreciation to the people whose names are in the credits but usually aren’t really considered direct part of the "creative process." Cover Story is a reminder about much of comics is a package deal, that many hands are involved and that — unless given that peek behind the scenes — one can never be sure who came up with which idea. All of this is purely sub-textual, at no point does Smith suggests he deserves more credit than he got; most of the actual text pieces are closer in spirit to blog posts than proper analysis.

That is the problem with the book. It makes a promise it does not doesn’t really fulfill. It promises a deep dive but stays in the shallow end of the pool. A better book, might present fewer covers but give the readers more insight into the creation process of each one. Or it might leave some room to discuss the place of the cover in commercial comics, its paradoxical place as piece of art that is also a commercial to the stories hidden inside.

"Commercial" is a necessary word here. While the stories within the covers of 2000 AD are works of commercial art, the covers are commercial art. They are, first and foremost, a sales pitch. Smith mentions it off-handedly when discussing the first cover of the book (prog 193, drawn by Mick McMahon): “I redesigned the logo when I became art editor […] it always stayed central, because remember in those days there were lots of comics on the newsstands, so you have to stand out” There’s little discussion about the realties of "selling" the issue, the covers are either "good" or "bad" in terms of the artwork involved, as if divorced from the tawdry reality of the enterprise.

To me the tawdry reality is what makes the idea of this book fascinating. Take the cover for prog #415 (another one by Ron Smith): it is typically excellent work by both Smiths, big and bold and eye-catching, with literal eyes even! It's so good that it is easy to ignore that this piece of art contains not one but two ads for products other than the comics itself: the top line mentions “Free inside! 6 ‘Masters of the Universe’ stickers,” while the bottom right corner boasts “big prizes to be won in KP alien spacers competition.”

Art by Brian Bolland, text by Robin Smith.

Art by Brian Bolland, text by Robin Smith.This is hardly the first, and certainly far from the most intrusive, commercials for various knickknacks on the cover. After all, the very first issue of 2000 AD dedicated about 80% of its cover space to a “free space spinner” gift. The first cover Robin Smith draws himself in this book, prog #265, has a typical stern-looking Judge Dredd, right next to a bubblegum advertisement with a new cola flavor. It almost reads like a subversive take on the silliness of the Judges, but no – they just got stuck with ads and smith had to fit it in somewhere, somehow. To me, that’s fascinating. A much better subject than a dozen "good" covers that exist (according to this book) as a piece of art almost separate for the story, transcending crass commercialism.

Cover by Robin Smith

Cover by Robin SmithIt is when crass commercialism invades the world of art that Cover Story comes alive. It's a reminder of the constraints that forces the hands of the artist. You can try and do the best work you can but you always end up serving several masters at once. That doesn’t mean "art" is impossible to achieve in such conditions, some of the covers therein are (to me) very fine pieces of art. But they are not "fine art." They are something else. Not a hot dog, but not a painting aiming at the eternal. These ads on the cover are a reminder of the birthing process of comics, across newspapers and magazines, as part of a giant commercial enterprise. These occasional reminders of the reality of comics-as-a-business are what gives Cover Story whatever artistic value it has beyond just another recycling of the past. You can bask in the glory of "what was" but never forget the context in which it was made.

These comics aren’t sausages. Not even the finest cook gave so much personal attention to any singular sausage. But they are part of the same process in which sausages are made. I like a good Judge Dredd story as much as anyone, and I think they have a lot to offer; still, even today, when ads on the covers are a thing of the past. That element hasn’t been replaced by l'art pour l'art. Cover Story helps to remind you that Judge Dredd might be “a warning, not a manual” (according to Molcher), but he is also an occasional gum salesman.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·