Tania De Rozario | February 9, 2026

Weng Pixin photographed by E. Weng

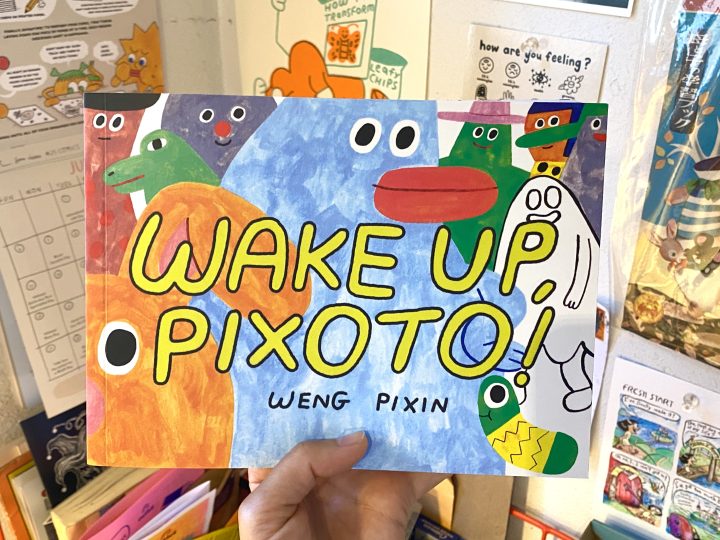

Weng Pixin photographed by E. WengWeng Pixin is an comics maker, illustrator, painter and educator born and based in Singapore. Her most recent work, Wake Up, Pixoto! (Drawn & Quarterly, 2025), chronicles her time as an art student, focusing on her gradual immersion into a cultish group led by her former art instructor. Pixin and I attended the same art college but didn’t really connect with one another while we were there - comics reunited us in recent years (thank you, Vancouver Comics Arts Festival!) and left us bonding over Singapore, our interest in cults, and of course, her most recent book. We talked about it in December 2025, the way any pair of writers might converse across miles of space and time in today’s digital age - over a hybrid combination of Zoom calls, Google docs, emails and Instagram messages.

TANIA DE ROZARIO: It is great to be speaking with you again. I’ve really enjoyed getting to know you and your work through this third book.

WENG PIXIN: It is lovely to be chatting with you also. I feel like I’m in very safe hands, considering the content or nature of my latest comic book…so I’m really looking forward to our conversation here. Thank you for doing this with me.

No, thank you! Autobiographical writing can make one feel so exposed. But sometimes talking about it can make one feel even more vulnerable.

I’ve learned to develop a somewhat thick skin to protect me, in the years of making autobiographical comics.

So you as may know, I have read all three of your books and it has been very interesting observing the trajectory of your work. The formal qualities of your work have changed a little bit along with your modes of narration - for example, moving from shorter separate stories to more longform writing. How else do you feel you work has evolved or stayed the same?

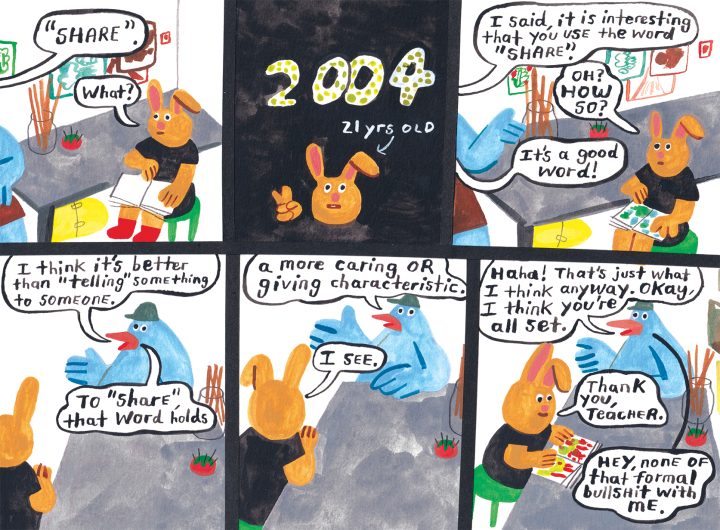

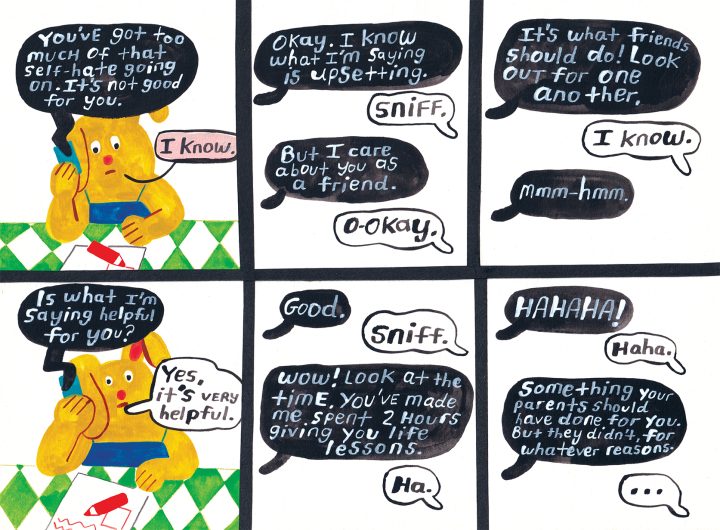

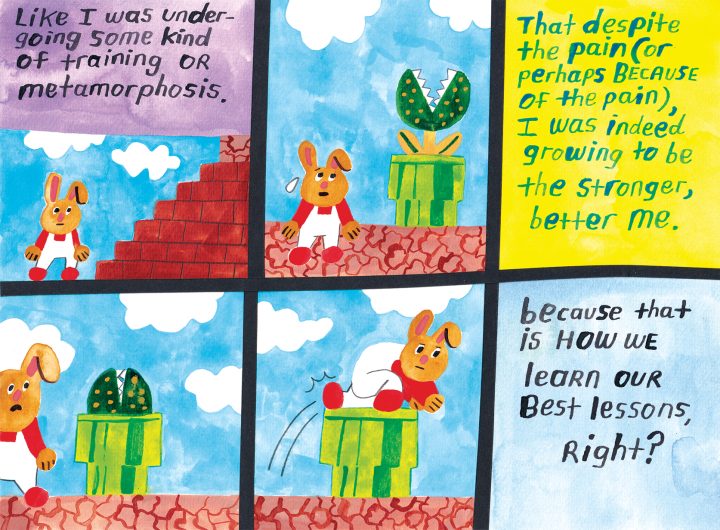

I often describe Sweet Time as a book that contains my experimental phase as a young comics artist, and Let’s Not Talk Anymore as a reflection of my interest in longer-form storytelling. In Wake Up, Pixoto!, I think I found a storytelling voice that combines “serious” and “funny” in a way that resonates for me. The ‘funny’ isn’t to dismiss or make light of the content of my story - rather, humour here functions quite like a bag of comfort food for my treacherous and uncomfortable hike up a mountain, so to speak. In my older works, I tended to let the voice of a younger part of me that I considered to be highly dramatic, romantic, seeking and yearning (but also somewhat a hot mess) be afforded the space to vent and express herself. These days, I tend to work with the curious and introspective part of me when making my comics.

the highly portable Wake Up, Pixoto! by Weng Pixin (Drawn & Quarterly, 2025)

the highly portable Wake Up, Pixoto! by Weng Pixin (Drawn & Quarterly, 2025)I see - this segmentation of the self. But would it be accurate for me to say that despite the difference in voice, one element that threads your stories is that you work primarily in nonfiction?

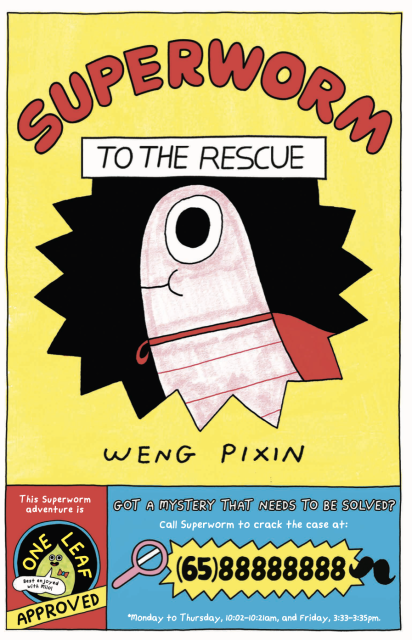

Yes, I work primarily in nonfiction and that my comics are largely drawn from my lived experiences. I wouldn’t say they are strictly 100% nonfiction, as I do occasionally weave in elements of imaginary, ‘what-if’ scenarios into some real stories - particularly in Let’s Not Talk Anymore and some short stories in Sweet Time. So far, comics made for young readers like Superworm #01: To the Rescue (originally published in French by Monsieur Ed under Super Lombric #01: À La Rescousse), are my more fictional works. I’ve not gotten into fictional comics and stories for older readers at the moment (and I don’t know why!).

Interesting! Do you create any nonfiction comics for younger readers?

At the moment, no! Although…come to think of it, most of my fictional comics for younger readers do contain some characters or elements that were inspired by real experiences. For example, Superworm is an earthworm whose super skill lies in its ability to locate its friends’ missing belongings. This stemmed from my experiences managing an art studio for kids, where, kids being kids, they very often leave their belongings behind after art classes: water bottles, caps, one sock (always very mysteriously, just that one sock!), a favourite plushie or toy…to name a few examples. And for Superworm #02: The Case of the Rosebud (this comic book is available by early-mid 2026, published in French under the title Super Lombric #02: L'Affaire Du Bouton De Rose), I was working on Wake Up, Pixoto! while plotting the ideas for it, hence there’s a character in there named Toby the Gnat, who is demanding, controlling and bullies its followers into doing all the work while he enjoys relaxing and making tons of farts. Quite like a typical, run-of-the-mill cult leader!

Yeah, cult leaders are totally full of farts!

Haha, they definitely are full-of-shit…in hindsight!

Superworm #01: To The Rescue by Weng Pixin (Epigram Books, 2025)

Superworm #01: To The Rescue by Weng Pixin (Epigram Books, 2025)Absolutely. But before we get into the heavy autobio stuff, I do have a questions I’ve been wanting to ask you about one of the formal elements of this most recent book, as well as the previous two. What prompts you to work in landscape format through all your work? I find this to be a less common choice in the world of comics. What drew you to this format and what keeps you there? I notice you tend to work smaller that a lot of other artists as well.

I’ve been trying to figure that out myself! I have some comics made in portrait-format, like my for-children comic Superworm #01: To The Rescue …but I’ve not come up with any proper answer to why most of my comics involve the landscape format while a few are in portrait mode. There is something about the landscape format that allows for emotions to emerge easier for me, whether it be the emotional resonance of a particular scene, or a character’s internal going-ons. That said, I’ve read comic works in portrait-style that are emotionally impactful and leave me with a sense of “Woah, I need to remember to breathe here because this is leaving me with so many complicated feelings right now”; where I’m really connecting to the story in such a heart-to-heart manner. So yeah, it remains a bit of a mystery why I’ve not utilized the portrait format very often when it comes to my own processes.

As for scale-of-work, Let’s Not Talk Anymore and Wake Up, Pixoto! were both made on A4-sized drawing papers and shrunken down for printing-purposes. The recent switch to using smaller papers is simply to offer myself a bit of difference or variety and to see where that takes me.

So many creative processes are a mix of analysis and intuition - there are some things we know by skill, others we know by gut. Oh! And speaking of analysis -critical analysis specifically- we talked about Singapore recently, and you mentioned that you didn’t feel there were opportunities in school or at home where you were encouraged or prompted to learn or practice healthy skepticism. You also mentioned that the act of questioning people who were in positions of authority was generally frowned upon. Has the act of making this book and putting it out into the world therefore felt counter-cultural to you?

I’d recently did an interview with the New York Public Library to talk a little bit about Wake Up, Pixoto!, and a teacher asked during the Q&A (and I’m paraphrasing here): “...but isn’t young adulthood a time to be learning critical thinking skills and also learning what types of adults to trust or not to trust?” I want to add that she mentioned her question came from a place of curiosity and not of judgement, which I really appreciated. It is true that I come from a culture that doesn’t provide me with much learning opportunities to question my elders and persons in positions of authority. One of the unhelpful lessons I learned as a child growing up in the 80s was that I had to be respectful of my elders - this included any person considered to be, hierarchically-speaking, “above” me. Like a teacher, for example. On top of that, and here is the part that I find to be deeply harmful: I was taught to also be mindful of their feelings. So even if they were just plain wrong, I was taught to not question them or to not say anything to hurt their feelings. I was left with the disorienting choice to keep quiet and walk away, and persons who had misused their positions of power could move on without knowing the consequences of their actions, facing little to no repercussions to their objectively bad behaviours.

I’m sorry that you experienced this. When you say you come from a culture that did not provide you with too many learning opportunities to question authority, are you referring to Singapore culture at large, or the culture you inherited from the family you grew up with?

Hmm. I would say, Singapore culture and specifically Singaporean-Chinese culture (that’s where I’m from) and within my own family - yes to all that. Where there appears to be more value placed on ‘maintaining harmony’ than on truth-telling. I feel that the notion of ‘harmony’ here isn’t quite built on sufficient openness or acceptance, but rather, on a bed of discomfort, compliance and moreso, fear.

So in a sense, yes - it does feel counter-cultural from where I come from, to tell the story I am telling. Making the book went against the grain of my upbringing, which in and of itself also felt counter-cultural. Making Wake Up, Pixoto! meant meeting the younger, pre-cult me whose upbringing held lessons that were not helpful and put her in harm’s way. It also meant meeting the cult-me who gradually became more vulnerable, confused and helpless. Wake Up, Pixoto! allowed the older, stronger me to speak on their behalf. I cannot change the persons in power and authority who misused their power, which in my case was my former teacher. But I can at least empower the younger me who felt stuck and harmed within the coercive and psychologically-shredding system, and offer her a voice to speak, instead of staying silent and walking away.

I love this for you. For all versions of you.

Thank you!

I think something very special about engaging with memoir is the fact that we are often travelling back into the past to engage with our former selves in a way that is very symbiotic - often, our past experiences inform our current insights and our current insights, in turn, give new meaning to our past experiences. These come together in ways that help us navigate the future.

I agree with you completely! Especially with how current insights can grant new meaning to our past experiences…and that’s what I love so much about art, in its offer for us to create and transmute life into something more. It was pure coincidence that I decided to write Wake Up, Pixoto! almost a decade after my (cult) experience. In hindsight, it was a good coincidence as sufficient time had passed, and the distance provided the capacity for me to approach the subject and its contents in perhaps a more responsive rather than reactive manner.

Absolutely! For me, time is always essential to the telling. Some experiences require more time, some require less. I know that one thing we both spend a lot of time thinking and reading about is cults - religious and otherwise. And one thing we’ve always come back to is how there are many misconceptions about what makes someone susceptible to recruitment. Could you speak more to that?

Yes…unfortunately one of the biggest misconceptions is that a person’s lack of intellect is the cause of them falling into a cult. This is likely due to a mix of little-to-no education around coercion and undue influence, and newspaper headlines and documentaries that sensationalize the practices and consequences of dangerous cults, which of course make most people think “there’s no way I would choose to do that.” I was certainly one of them until it happened to me. These headlines or shows tend to neglect ‘the how and why’ by not clarifying a person’s initial attraction to a group’s beliefs and values. Sometimes, they even skip out entire much-needed conversations around gradual coercion and how that presents itself, which typically involves a progressively slow process of withholding options and choices - this withholding is often rationalised as (or twisted into) something supposedly beneficial for the member.

The more accurate reason why people get themselves tangled up in a harmful cultic dynamic or group is a person’s vulnerability at a certain point in their life. This can be caused by stressful life circumstances like a job loss, a move from one country to another, divorce, break-ups, being diagnosed with a serious illness…and many others. Think about the recent global COVID-19 pandemic, for example. I am sure some people have stories to share about how they were surprised to discover that someone they know (a family member, a friend, an acquaintance, a colleague…) was expressing beliefs in the deeply irrational or illogical during what was a very scary and stressful time in many peoples’ lives. Other times, it could be a matter of finding yourself wondering or feeling like you just aren’t doing enough, or that you are not hitting some goal you’d hoped to have achieved by some point in your life. This can leave one with increased amounts of self-doubt, loneliness and in a more concentrated search for quick meaning and answers.

Now add one of those situations above with just the plain bad luck of meeting a person or group that claims to be available to offer you support, community and answers to whatever is troubling you when you are already pretty isolated, scared, exhausted or overwhelmed…that is what makes a person more susceptible to falling into a questionable situation.

In my case, I did initially keep my distance from TL (the pseudonym I used in Wake Up, Pixoto! when referring to my former art teacher) despite his bids for friendship during and even shortly after my graduation from school. My gut alarm system was working better when I wasn’t under significant mental distress. What led me to TL’s orbit was a very difficult break-up two years after I graduated. He found out about it and offered his time and guidance during this particularly difficult period of my life. Of course, what I did not anticipate was that I would eventually come to be stuck on some tediously long path of ‘self-growth’ which ultimately left me feeling hollowed out, like a mug with no bottom.

I am very drawn to what you said about your gut alarm system working better when you weren’t under significant mental distress. It reminds me of how chronic anxiety and distress can significantly weaken and dysregulate our immune systems. Maybe our gut alarm system is what keeps us immune to bullshit!

You mention susceptibility as well. Do you think there might have been any factors outside yourself that might have helped lessen susceptibility? Is there something you know now that you wish you knew prior to the moment you were recruited, that you think might have helped you avoid being trapped or maybe helped you leave earlier?

Looking back, it would have helped if therapy wasn’t so stigmatised in Singapore in the 2000s (though it is better now) - I would have sought therapy earlier when trying to cope with my heartbreak. Unfortunately, there are also cases of people falling into therapy-type cult dynamics or groups led by clearly unprofessional and unethical therapists. So this is where I feel a practice of checking-in with myself would have helped a little. Asking “What do I feel right now?”, “What do I need?”, could have kept me more connected to who I am instead of leaving me pressured to feel and think in TL’s prescribed way. Instead of dismissing my immediate feelings whenever TL said or did something that left me feeling weird, uncomfortable or some type of odd way, greater awareness and connection to my emotions –and by extension, greater trust in my gut instincts– would have at the very least, helped me acknowledge and make note of what I was really feeling, - even if I had yet to cognitively understand or recognise what had happened. I do believe a more robust emotional awareness and emotional intelligence creates better protection against people like TL. They can attempt to twist your mind into thinking a particular way to suit their needs, but that would have been all the more difficult if I was more connected to my body and emotions, and listening in to my alarm bells’ rings and dings of “something’s not quite right here”.

I totally agree with you. Simply recognizing and taking note of an emotion can make all the difference in a multitude of situations. I also agree with you about therapy being stigmatised in 2000s Singapore! As someone who was dealing with a lot of trauma in the 90s and 2000s, I would add that therapy also felt extremely inaccessible. I ended up turning to art and writing as way of working through that trauma. I wonder whether the initial impulse to make this book sprung from a similar desire?

I know you can’t see me, but I’m simultaneously nodding and shaking my head to what you’ve mentioned, like one of those bobbleheads. I relate to the helplessness you’ve described here, and I am frustrated that you’ve had to experience all that.

Traumatized Bobbleheads unite!

In thinking about my impulse to make Wake Up, Pixoto!, I recall a line from your beautiful and at times very heartbreaking book of essays, Dinner on Monster Island. I have a number of favourite essays, and one of them is titled I Hope We Shine On, where the story begins with you receiving an email from someone, and the complicated stirrings that emerged from there. Towards the end of the essay, you wrote “…the past always present, always requiring acknowledgement, tending to, overcoming, in order for the monster to be defeated”.

I love the inclusion of “always requiring acknowledgement”. It had this feeling of ‘here I am’, and of ‘wishing to be seen or received without judgement’. It is a beautiful wish and request that gets misunderstood quite often also, and I loved how you thread that into the story’s tapestry. For me, Sweet Time holds more pieces of my work where I was indeed working through a lot of really messy experiences prior to seeking professional help…whereas in Wake Up, Pixoto!, the impulse was more akin to the feeling I connected with in I Hope We Shine On- one of honouring my past’s request to be seen, so I can meet it and truly move on.

Thank you so much for the kind words about Dinner on Monster Island. As you know, that collection is also one in which I am in conversation with several past selves - as such, I am wondering what the process of making Wake Up, Pixoto! looked like. Did research overlap with creation? You have mentioned having conversational-research with several individuals drawn as recurring characters in the book. Did these conversations take place over the course of the book’s creation? Were they formal interviews? Did participants have direct input in any of the content?

The process was mostly unstructured and organic. I spent some time having informal conversations with former friends (members) of TL, most of whom were ex-students of his too. It was interesting how a number of them used the word ‘weird’ to describe their memory of TL. I often opened our conversation with a prompt like, “What’s your memory or impression of your past connection with TL?” and within their first sentence, the word ‘weird’ would pop up. I sometimes wondered if the word ‘weird’ was used to maybe describe being gaslighted, coerced, being made to listen to TL’s very lengthy monologues that wove a mix of universal truths alongside his rather questionable opinions touted as ‘truths also’, of being guilt-tripped or simply absorbing TL’s projections…to name a few examples. But if one isn’t sure what these phenomena are called (like I was!), it would make a lot of sense to use the word ‘weird’ as a handy descriptor.

All of them expressed the wish for their experiences with TL to be kept private and confidential. These conversations weren’t facilitated to gain content for my work, but rather as a way for all of us to take the time to share, and to close this particular chapter in our lives. Importantly, it was also to remind some of us how we weren’t ‘weak’ for declining to think or make choices in a manner that fit TL’s version of ‘the idealistic artist life’, and that it is okay to live in a way that honours our own needs and desires. Once conversations with former members were completed, I spent some time recording my memories in a notepad, and limited my exposure to many cult-related documentaries and cult survivors’ memoirs so I could stay with the act of writing my experiences in my own words. The only book and helpful resource I would occasionally refer to during the making of Wake Up, Pixoto! Was An Everyday Cult, a memoir written by Gerette Buglion. Gerette is an educator and cult-survivor who wrote of her experiences of being inside what she called ‘an everyday cult’. An everyday cult is one where you have the freedom to be at any place you wanna be, wear whatever outfit you wanna wear, meet whoever you wanna meet - you have a basic sense of autonomy and independence, and yet, you are still under the undue influence and control of a cult leader. My experiences are a lot closer to Gerette’s, so her book was very helpful to refer to sometimes whenever I felt somewhat lost in trying to find the words to describe something intangible.

In that sense, there’s not much direct input from former members on the final work and its contents. But speaking of input, some conversations with my non-cult-friends were the ones that did make it into the book. For example, Jam Ham (pseudonym of course), my then-roommate, would ask me questions like “Why would you stay in such a situation?” or “What would happen if you declined to help him?”-- questions which I imagined somebody else might be wondering too. So I included those and provided my answers to them. There were many more instances like these where a friend would ask something which I felt was important to discuss. Or we would be chatting and I’d be reminded of yet another thing TL did that I felt would be helpful to further explore in the story. This was going on while I was writing and painting the comic pages. The comic was like a living creature inhaling and exhaling, absorbing and occasionally throwing up while it grew to become who it came to be.

Wow. This idea of a book or story or comic inhaling and exhaling and throwing up is very resonant! I also like the idea of art throwing up because it suggests that for art to live and grow, it must be fed. What feeds your practice? Both the creative, intellectual elements of your practice, as well as the practical, logistical elements of your practice (such as making time to actually create, and protecting your body from repetitive stress).

I have a memory of how, some years after cutting contact with TL, I gradually grew aware of the fact that I was experiencing immense difficulty trusting myself and others. This was inadvertently affecting my art also. For the first time in my life, I was experiencing little-to-no joy nor motivation to create or work on anything art-related, which was very worrying.

I confided in my Dad, telling him how I was really struggling but I hadn’t a clue as to what was causing my pain. At that time, I hadn’t put two-and-two together about how I had left a cult-like situation, or how I hadn’t made sense of a number of troubling experiences even prior to my recruitment into the cult. Whatever I had swept under the rug before had now accumulated into this suffocating mass of terror and helplessness. My Dad turned to me and said that one of the earliest memories he had of me as a child was of how brave and fearless I was. According to my Dad, I was about three or four years old when he took me along to visit his best friend, who had just gotten a new pet - a German Shepherd named Bravo. My Dad spoke of how he was very surprised to see me walk right up to Bravo and without hesitation, offer my hand for Bravo to sniff. Our conversation ended with my Dad saying something to the effect of, “I know this brave and fearless you, is inside of you.” Putting aside the possible loopholes to his story, I think it was my Dad’s belief in me which gave me a bit of much needed strength.

Weng Pixin's work table

Weng Pixin's work tableEventually, I did reconnect to this ‘brave fearless me’ with the help of an incredible therapist, M. The process of recovery felt like I had discovered my own Calcifer (like the fire character from Howl’s Moving Castle) who had been living inside of me all along, but had been dimmed by past wounds and harmful lessons from my upbringing. M helped point out to me where the logs were, so I could reach over and grab some, and ignite my own fire again. I don’t know where my Calcifer came from though, but I do know that she is very alive and is generally responsible for feeding my practice as an artist.

This makes sense. You reached back in time to give your younger self a voice, and she reached right back towards you, and helped you make this book. What an honour it has been witnessing the work you have made together. Thank you for having this conversation with me.

Thank you for your lovely questions and having this conversation with me also!

English (US) ·

English (US) ·