Greg Hunter | February 3, 2026

We’re in the multiverse now, inevitably, entering a dimension parallel to our own. The one critical difference? Last September’s Deadpool/Batman (Marvel Comics) and November’s Batman/Deadpool (DC Comics) are not only the publishers’ latest crossovers but their final superhero comics. The vanishing point of print superheroics. This is strange territory, but its lights can illuminate our own lands — the comics, our last, best lenses on the genre.

A unifying factor between this end-days dimension and ours: it’s been years since Marvel and DC have offered readers a team-up. Between that and the popularity of Batman and Deadpool, their profiles beyond print media, these two books mark as big an event as the Big Two can offer, which makes them a useful measure of public awareness. Comparing Deadpool/Batman and Batman/Deadpool to The Death of Superman or the launch of X-Men under Jim Lee and Chris Claremont suggests supercomics' diminished profile. Countless factors have contributed to this, many of them outside the publishers’ control. (Imagine the difference the continued presence of comics at gas stations and Targets would make for releases like these.) Still, the marginal visibility of these new team-ups reminds us of the publishers’ failure to convert viewers of the Deadpool or Batman films into readers.

In this dimension, Deadpool/Batman and Batman/Deadpool also document the final forms of superhero scripting and cartooning. What we see on the level of craft doesn’t tell the full story of an unrealized readership, but the problems the comics have are endemic to print superheroics. Despite big differences in their execution, Deadpool/Batman and Batman/Deadpool both have narrow visual horizons, with art subordinate to text. This persists despite the companies valuing writing differently at different times.

In this dimension, Deadpool/Batman and Batman/Deadpool also document the final forms of superhero scripting and cartooning. What we see on the level of craft doesn’t tell the full story of an unrealized readership, but the problems the comics have are endemic to print superheroics. Despite big differences in their execution, Deadpool/Batman and Batman/Deadpool both have narrow visual horizons, with art subordinate to text. This persists despite the companies valuing writing differently at different times.

Deadpool/Batman comes years removed from Marvel’s last major writer-forward moment. Brubaker, DeConnick, Fraction, Hickman — however a reader rates any of them individually, these writers shared a level of storytelling ambition, and built up equity with readers through their relatively novel takes on well-loved characters. Zeb Wells published his first Marvel pieces around the same time, but found a role closer to that of writers like Dan Slott, the steady-handed franchise stewards. He made his name on stories like the Amazing Spider-Man “Shed” arc, an example of the minor revisionism that has become one of superhero comics’ favored modes. Readers learn in “Shed” that Curt Conners actually likes being the Lizard. It’s a comfortably bracing ten-degree pivot, a shuffling-around of bricks that happens when there’s not much room to build, and about as much change a writer can give weekly comics-buyers before someone utters the phrase “ruined my childhood.” In Deadpool/Batman, Wells is coordinating the encounters readers know to expect, a comics scripter as professional meeter of expectations.

This first team-up gives the Joker a multiversal means of enlisting mercenary Deadpool to attack Batman, giving the villain a clear runaway for his latest evil plan. The story unfolds in a workmanlike manner: a first meeting, conflict, a couple upper-hand trade-offs, and then mounting who’s-kookier jealousy between Deadpool and Joker before Deadpool lands on the side of justice and the crisis resolves. The comic’s best gag reveals Deadpool’s awareness of the conventions of these team-ups, including the Batman-Captain America stand-off in JLA/Avengers. Swiftly outclassed during early sparring with Batman, Deadpool pleads, “Okay, wait! You’re right! We’re too evenly matched!” It’s simple, effective, and Wells drags it out:

Batman: I never said that.

Deadpool: Look, we all want to know which one of us would win, but the point is we earned each other’s respect. That much is clear.

Batman: Clear to who?

Deadpool: What I’m trying to say is …

Deadpool: I can’t bring myself to murder you, Batman.

Batman: At no point was I in danger of being murdered.

Repeating a joke that worked fine the first time is not flagrantly bad writing, but the moment captures a tension common to these comics. Any time a writer doesn’t give a story beat enough room to breathe, they likely aren’t giving a story’s art room to breathe either, warping the architecture of a page. The writing, as it undermines itself, undermines everything.

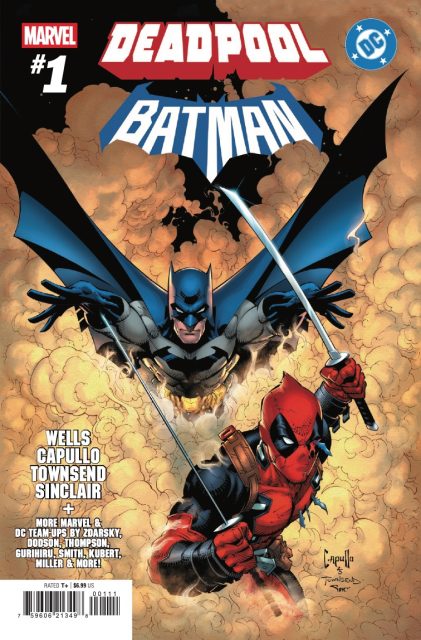

Page from Deadpool/Batman, written by Zeb Wells. Art by Greg Capullo, Tim Townsend, and Alex Sinclair. Lettering by VC's Clayton Cowles

Page from Deadpool/Batman, written by Zeb Wells. Art by Greg Capullo, Tim Townsend, and Alex Sinclair. Lettering by VC's Clayton CowlesIndeed, everything cartoonist Greg Capullo does feels circumscribed by Wells’s script. Capullo’s work reliably meets the story’s moments; it’s well paced and never confusing. But the comic’s most memorable visuals are mainly 2020s period signifiers like the Joker’s fade haircut. A trope of blog-era comics criticism was “Talk about the art,” with various writers-about-comics lamenting reviews that only analyzed superhero stories at plot level. This push, for all its good intentions, didn’t fully reckon with how utilitarian so much superhero cartooning continued to be. And despite the wish to think of superhero comics as a space of infinite possibility, it’s difficult to read Deadpool/Batman and think of what Capullo could have made more compelling out of the story’s formulas. Even one of Marvel’s great stylists from earlier decades — Steranko, Simonson, Marcos Martín — would be challenged to elevate something so committed to doing exactly what readers expect. This is the pyrrhic victory of the superhero scripter: to keep compositions at the mercy of excessive text and familiar incident.

A version of this has always been a feature of superhero comics, from the breathless narration of the normative golden-age comic book to the rhetorical flourishes of Alan Moore and Claremont. At times, powerful works have emerged. But even the genre’s high points over decades have often reinforced the fallacy of a need for overwriting, some false link between that and a comic’s perceived sophistication.

The Marvel method, most prominent during the publisher’s creative explosion of the 1960s, provided for more parity in storytelling between scripter and cartoonist, and for genre-defining collaborations such as Lee-Kirby and Lee-Ditko. Perhaps because it happened gradually, the reduced use of the Marvel method is not always treated as a discrete event in comics history. Here at the end, though, ultimate hindsight suggests Marvel’s phasing out of this approach is as pivotal a moment as any other. Given so many of the superhero genre’s fundamental strengths — color and shape, costume and design, dynamic movement — a reader wonders about a dimension where artists had more historical latitude as storytellers.

While Zeb Wells brings an oven-mitt safety to his team-up, Grant Morrison presents Batman/Deadpool with something like jazz hands, but both writers are the dominant forces in their issues. Morrison begins their contribution with a fractured in-media-res approach. The story cuts from a meet-cute between Marvel and DC’s embodied cosmologies to Batman following a lead from Gotham to Greece, and soon Deadpool is cradling the corpse of (a) Batman while pursued by cartoon ninjas. It’s not a million miles from Final Crisis, with a shaky readerly experience to match the contents of the story, but Batman/Deadpool features some cutesy apologetics as well: “Before you get all judgy,” Deadpool tells the reader, “that attention-grabbing opener comes with full context!” The story that unfolds is more of letdown than the one from Wells and Capullo, simply because Morrison at their best can do this all much better.

While Zeb Wells brings an oven-mitt safety to his team-up, Grant Morrison presents Batman/Deadpool with something like jazz hands, but both writers are the dominant forces in their issues. Morrison begins their contribution with a fractured in-media-res approach. The story cuts from a meet-cute between Marvel and DC’s embodied cosmologies to Batman following a lead from Gotham to Greece, and soon Deadpool is cradling the corpse of (a) Batman while pursued by cartoon ninjas. It’s not a million miles from Final Crisis, with a shaky readerly experience to match the contents of the story, but Batman/Deadpool features some cutesy apologetics as well: “Before you get all judgy,” Deadpool tells the reader, “that attention-grabbing opener comes with full context!” The story that unfolds is more of letdown than the one from Wells and Capullo, simply because Morrison at their best can do this all much better.

Until recently, a meeting between Deadpool and Grant Morrison seemed unlikely, but the character and writer have had oddly parallel trajectories. Both are examples of how the genre maintained some elasticity in its final decades. In the late 1980s, Morrison shifted from UK comics-anthology magazines to an attention-getting run on DC’s Animal Man before creating one of the defining titles of the Vertigo line, The Invisibles, in 1994. How we locate The Invisibles now is outside the scope of this piece, but whether a reader considers it a landmark intersection of genre comics and counterculture or a real you-had-to-be-there book, it made Morrison an unexpected candidate to return DC’s Justice League to the top of its superhero hierarchy. But they did, with Howard Porter and John Dell, in an excellent JLA run from 1997 to 2000.

From JLA followed projects such as Morrison’s New X-Men; the inspired, influential All-Star Superman, with Frank Quitely; and an ambitious multi-year, multi-series Batman run. The latter featured a variety of artists including Quitely and J.H. Williams, along with some career-best work from such cartoonists as Chris Burnham, and introduced characters (such as Damian Wayne) who became mainstays of the Bat-books. Although these works were published alongside creator-owned collaborations such as The Filth and Seaguy, they do not read like paycheck projects, nor do Morrison’s event books of the time. As much or more as Morrison’s other superhero works, Final Crisis and Multiversity deployed metafictional gestures, a purposeful disjointedness, and a general trust that readers could hang with something unfamiliar.

For all of that, Morrison’s greatest gifts as a superhero writer have been in dialogue and characterization, with formalism and metatextuality sometimes overshadowing their ability to write moments that are poignant, funny, and seem to reach a character’s core. With this new cross-company project, then, came the hope of the funniest Deadpool comic since issue eleven. Regarding Deadpool: it would be easy to write a bad-faith appraisal of this character, one that judges him by the measure of his most annoying fans, but this is less interesting than a reminder Deadpool was once the little comic that could.

In October 1998, around the same time Morrison dusted off Starro the Conqueror, Marvel held “Deadpool Month,” a marketing effort featuring one-shots designed to stoke the then-modest sales of the character’s monthly title, and a pretty remarkable reference point for Deadpool’s cultural ascendance in the decades afterward. It’s hard to hate any character that so effectively disrupted the genre’s rigid notion of its marquee heroes. Yet it’s easy to find Deadpool kind of a bummer, a concept that found its final form not in comics or even in blockbuster films but as a bumper sticker, a red-and-black glyph for the in-group signalling of people who still say “That’s what she said.” Even so, there are benefits to a self-aware superhero, one who’s designed to misbehave. How else do we get that moment when a hubcap dings Ed Skrein?

This was the modest promise of Morrison writing a Deadpool-Batman meeting. Grant can handle humor like few other superhero scripters. Even the “Hh” tic they gave Batman marks an ear for the character’s wry potential that few other writers have had. But what readers get in Batman/Deadpool is, if characteristically Morrisonian, a Morrison comic with the wrong nobs turned up. Cramped by history and verbiage, it is a work at the end of comics.

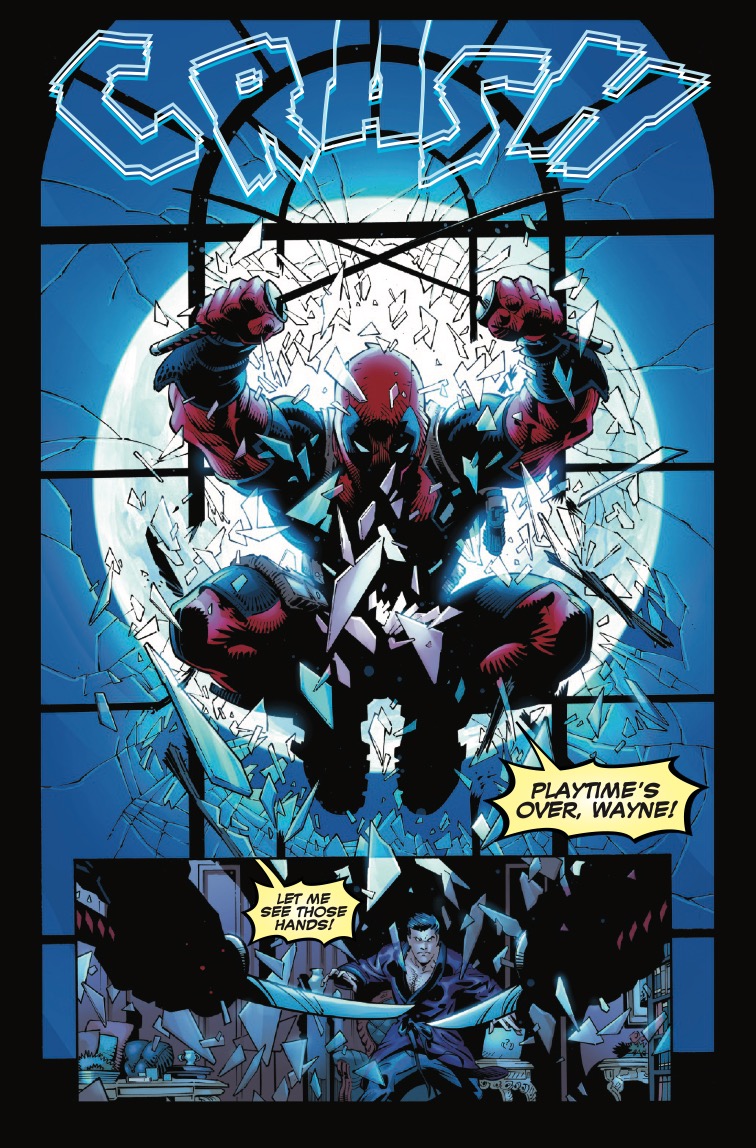

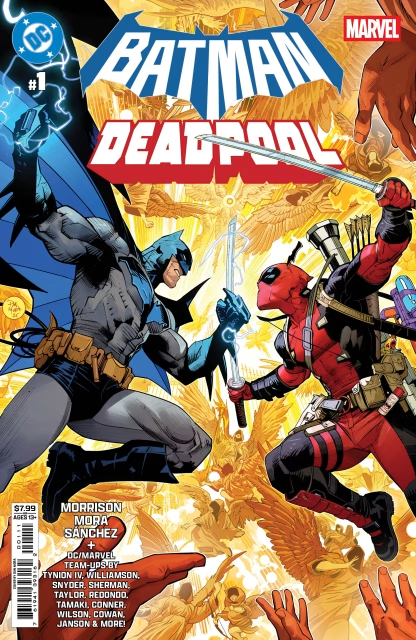

Page from Batman/Deadpool. Written by Grant Morrison, art by Dan Mora and Alejandro Sánchez. Lettering by Todd Klein.

Page from Batman/Deadpool. Written by Grant Morrison, art by Dan Mora and Alejandro Sánchez. Lettering by Todd Klein.The comic pits Batman against Morrison-Quitely creation turned onscreen Deadpool antagonist Cassandra Nova, both after the same reality-warping device. Batman has designed mental architecture to keep details of the device from interested villains (shades of Morrison’s RIP arc), and Deadpool, conscripted to stop Cassandra, encounters the other hero in this psychic territory. With various meta-commentaries along the way, including mention of Batman’s plot armor (oof), the hunt leads to the Writer, Morrison’s long-dormant DC self-insert, introduced back in Animal Man. Any pleasures here are complicated. The Writer’s appearance is probably a one-time occurrence, but a reminder that nothing stays buried at these companies, even when a scripter gives it the sense of an ending — not Damian Wayne, not Xorn, and evidently not even the Writer themself. Morrison’s move here reads vaguely like a process of converting a literary gambit from 1990 into Active IP, the step before something becomes a McFarlane Toys release.

Throughout the story, Dan Mora’s art suits Morrison’s script. His work is tight and functional, in the tradition of artists such as the Kubert brothers, and like Capullo’s, always easy to follow. And yet nothing here sticks in the memory. While the psychic terrain that hosts much of the story is theoretically grounds for inventive cartooning, Mora’s art seems hamstrung by having to visually catalog the script’s various references (in-story, clues to the nature of the reality-warping device). The result feels like the artist walking readers through a mall display, working his action mannequins into dynamic poses.

A reasonable response to this critique might be, First time reading a superhero comic? The industry-peak skills of a Dan Mora, the unmemorable end results — it’s not exactly a new phenomenon. But this is what the universal collapse of the genre calls for: to measure its works not by expectations lowered across years of Wednesdays but by their greatest potentiality. By that latter measure, Deadpool/Batman and Batman/Deadpool produce something like a phantom pain — the sense of missed opportunities genre-wide, maybe better realized in some other dimension. These works have been executed skillfully, in a manner that’s at the high end of industry convention and yet far afield from the genre’s best stuff, everything operating within a narrow band of the visible spectrum of comics.

Both releases come with multiple back-up pieces, shorter team-ups that give their own insights into what superhero comics were. In Batman/Deadpool, a meeting between Stephen Strange and John Constantine gives an example of how an artist’s style becomes a genre-wide visual trope. The story’s three scripters, James Tynion IV, Joshua Williamson, and Scott Snyder, are writing for artist Hayden Sherman, and throughout the story, ask Sherman to do J.H. Williams layouts. A climactic spread has nontraditional, often curved panel shapes in a roughly symmetrical arrangement; the center-most panels show Strange and Constantine coordinating their magics while outer panels show other mystic figures (Swamp Thing and Ghost Rider, Mephisto and Neuron) fighting elsewhere. The spread resembles stained glass, and resembles Williams’ virtuoso Batwoman work.

This article is making the assumption, yes, that the directive came from the writers — not a certainty, but plausible given the number of them. The choice matters in that the spread is the same place where an artist might otherwise have the most creative latitude. The presence of Doctor Strange makes the problem feel acute. In early Strange stories, Stan Lee wisely focused on verbal flourishes, with Steve Ditko defining their visual language.

Spread from "A Magician Walks into a Universe" from Batman/Deadpool. Written by Scott Snyder, James Tynion IV and Joshua Williamson. Art by Hayden Sherman and Mike Spicer. Lettering by Frank Cvetkovic.

Spread from "A Magician Walks into a Universe" from Batman/Deadpool. Written by Scott Snyder, James Tynion IV and Joshua Williamson. Art by Hayden Sherman and Mike Spicer. Lettering by Frank Cvetkovic.In the same volume, Mariko Tamaki and Amanda Conner pit Harley Quinn and the Hulk against mutated hotdogs. Tamaki inhabits different modes as a comics writer, including collaborations with cousin Jillian on books such as the subtle, contemplative This One Summer, and if there’s room for growth at the end of Big Two superhero comics, it’s likeliest to happen through a writer with Tamaki’s gifts. Yet sometimes the genre brings a scripter to its level instead. (See: Jeff Lemire, who did his best work early, in the spot-black poignancy of the Essex County stories, then seemed to lose something as a writer with every piece of work-for-hire lore manufacturing.) When the talent is present, it’s tempting to take a zero-sum view of these works: that time spent writing this kind of comic is time not spent on art with more interest in form or human interiority.

Harley Quinn deserves a moment’s attention, however, as 1B to Deadpool’s 1A, second only to that character in her twenty-first century ascent. There’s even a feminist praxis embedded in Harley stories, the argument goes. While Deadpool shifted from cult character to franchise player, Harley went from mistreated costumed moll to the girl who gets to have fun, an unapologetic brat in the Charli parlance, not just avoiding a fridging but blowing up the fridge. All of this, conceptually: good. It’d be great if it had led to better comics. But the Harley-Hulk back-up, in its self-conscious irreverence, recalls the stuff Freakazoid used to crib from Madman, and reads like the work of a savvy writer who knows exactly how hard to try.

A figure with his own altered trajectory, Frank Miller, contributes a meeting between “Dark Knight Universe” Batman and "Old Man Logan" Wolverine to Deadpool/Batman. His name in fine print on the volume’s cover reminds us of his shrinking stature — in an earlier era, any piece from Miller would have been the project’s crown jewel — and that even the most fixed positions in the canon are changeable. The comic we get is brief, barely more than a gag cartoon, and most resembles some of Miller’s polarizing cover work from the last decade. A few of its panels, reveling in the craggy, brutalist qualities of Miller’s late-stage cartooning, are still as visually compelling than anything else in the book.

Where Miller has landed is a phenomenon that shames the artist and a large segment of superhero readers alike. Although he has developed odious social-political views, and alienated some fans as a result, his lost prestige seems to have as much to do with the geometry of recent works — cartooning that’s simply too weird for a sizable readership, the one that thinks of contemporary comics art in terms of improved video-game graphics. Good-bye to all parties involved.

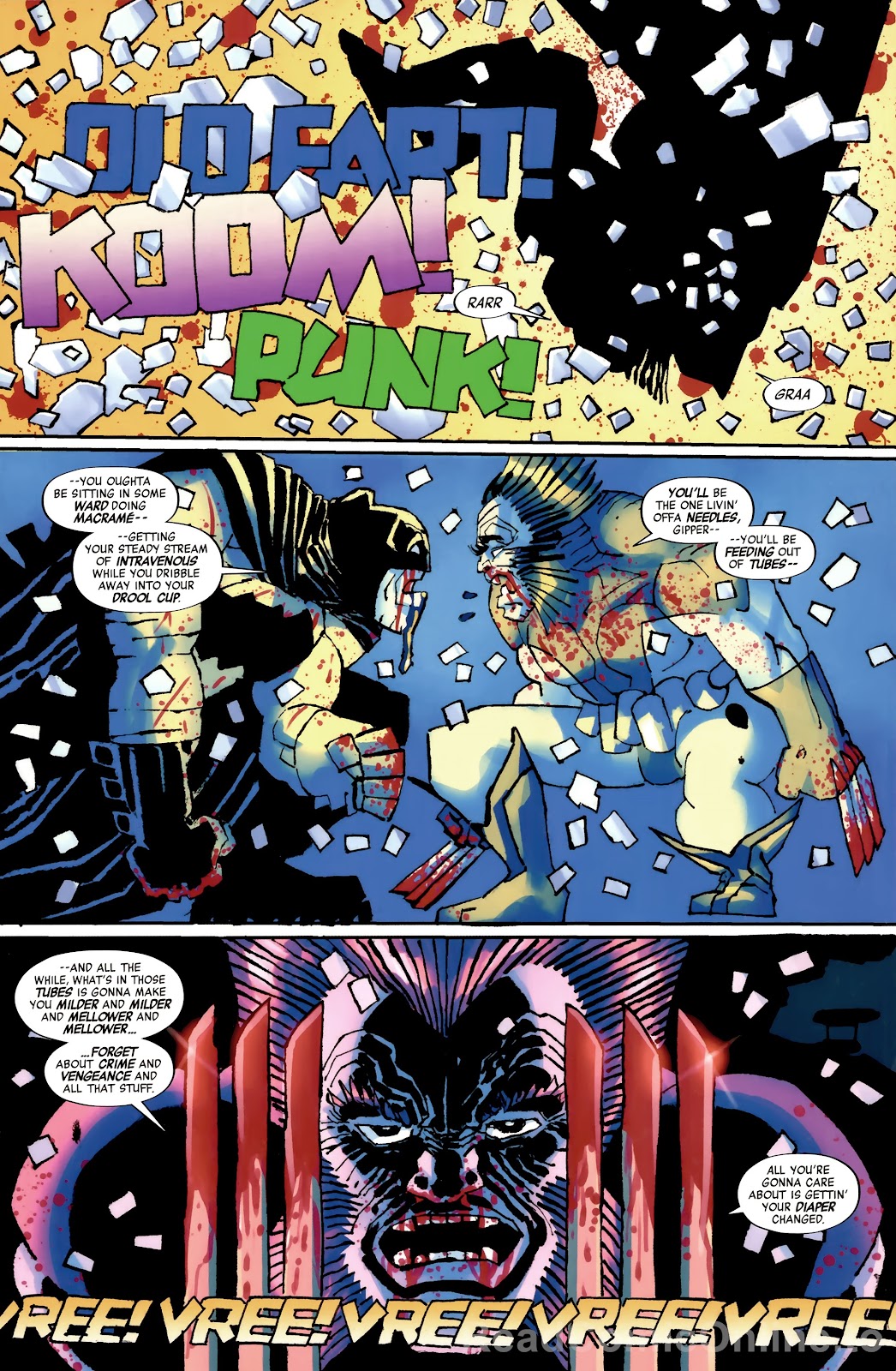

Page from "Showdown" by Frank Miller. Colors by Alex Sinclair. Lettering by VC's Joe Caramagna

Page from "Showdown" by Frank Miller. Colors by Alex Sinclair. Lettering by VC's Joe CaramagnaKevin Smith, another comics celebrity of sorts, scripts a Green Arrow-Daredevil meeting for Adam Kubert, in the two volumes’ worst and weirdest offering. (This is despite the best efforts of Kubert, who shows up in fighting shape.) “The Red & the Green” reads like Smith using the limitations of a back-up-comic to attempt team-up banter under compression, a bizarre hyper-patter: “Now that my case is closed, what say we leave this foreign fat cat and his flunky friends for the cops and go get us a drink, Red? I’m buyin’.” “Then I hope you have some green, Arrow.” For those of us advocating for adventurous work within the genre, Smith’s script is a humbling reminder of what such a call can bring.

The run of back-up pieces throughout Deadpool/Batman is mostly memorable for how it invites readers to imagine: what if Cap settled for a stern finger-wag on the cover of Captain America #1? Chip Zdarsky’s contribution, with art by Terry and Rachel Dodson, pairs Captain America and Wonder Woman, and takes an approach similar to Zdarsky’s Spider-Man project Life Story, tracing an imagined shared continuity across decades. It begins during World War II, with Steve Rogers poised to kill Adolf Hitler, and Diana encouraging him to reconsider. The piece attempts a nuanced look at the difference between justice and vengeance, animated by the idea that retribution against even an evil as great as Hitler’s ought to follow due process. There’s also, with Wonder Woman’s call for restraint, a form of accidental super-camp in the tradition of “My ward, Speedy, is a junky!” While this article’s stance on extrajudicial killings is against, the Zdarsky-Dodsons comic is too sentimental to effectively prosecute its case; less morality play than moral burlesque, its clumsiness is a disservice to its politics.

The gift of their piece, here in this collapsing corner of the multiverse, is a final reminder that the genre has always been a wildly unreliable way to engage with dilemmas of more than a modest degree of real-world complexity. Even the most celebrated examples tend to be worse than they appear in the genre’s self-serving collective memory. Superhero comics often reduce big questions down to their own generic terms, rather than opening them up, with Zdarsky’s story the latest and last example of scripters’ chronic inability to resist discourses that demand tools the genre doesn’t provide.

A vexing element of this is that decades ago, Jack Kirby intuited how to handle moral concerns within the super idiom, around the same time his clod colleagues were calling him Jack the Hack. Works like The New Gods or his return to Captain America capture moral conflict on the level of intensity and emotional meaning, recognizing that the genre’s strengths are in the heightened, the operatic. These comics provide a model through the tension they convey in the artist’s line — dynamic, distinctive, morally charged. Here as elsewhere, Kirby is king.

This is the thing: the potential of the superhero genre is not strictly theoretical. There are examples of how to nail these stories, not just in the largely self-directed cartooning of Kirby and Ditko (and later the best of Miller and Simonson) but in other works that leave artists the freedom to flourish. The superhero genre has gone further than most other comics traditions in differentiating story and art, often subordinating the latter, which at least leaves the possibility that these values can be adjusted. Grant Morrison’s work at its best achieves a satisfying balance — through their writing to the strengths of an artist like Frank Quietly, yes, but also in Morrison writing nimbly within greater restrictions. JLA, for example, featured a sense of play, attention to character, and generous staging grounds for Howard Porter’s porcelain gods, Porter’s figures are unreal enough to distinguish them from Dan Mora’s mannequins. Deadpool/Batman and Batman/Deadpool mark the superhero tradition’s last crisis, but this time it’s a hostage situation, the genre pinned down by creators and readers who seem most preoccupied with whether Batman’s utility belt looks lore-accurate.

Imagine the best version of the end, then: what might follow a scorched earth. This hope is only logical, after all. Nothing here dies forever, but an ending would be useful right about now.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·