Daniel Meyerowitz | September 3, 2025

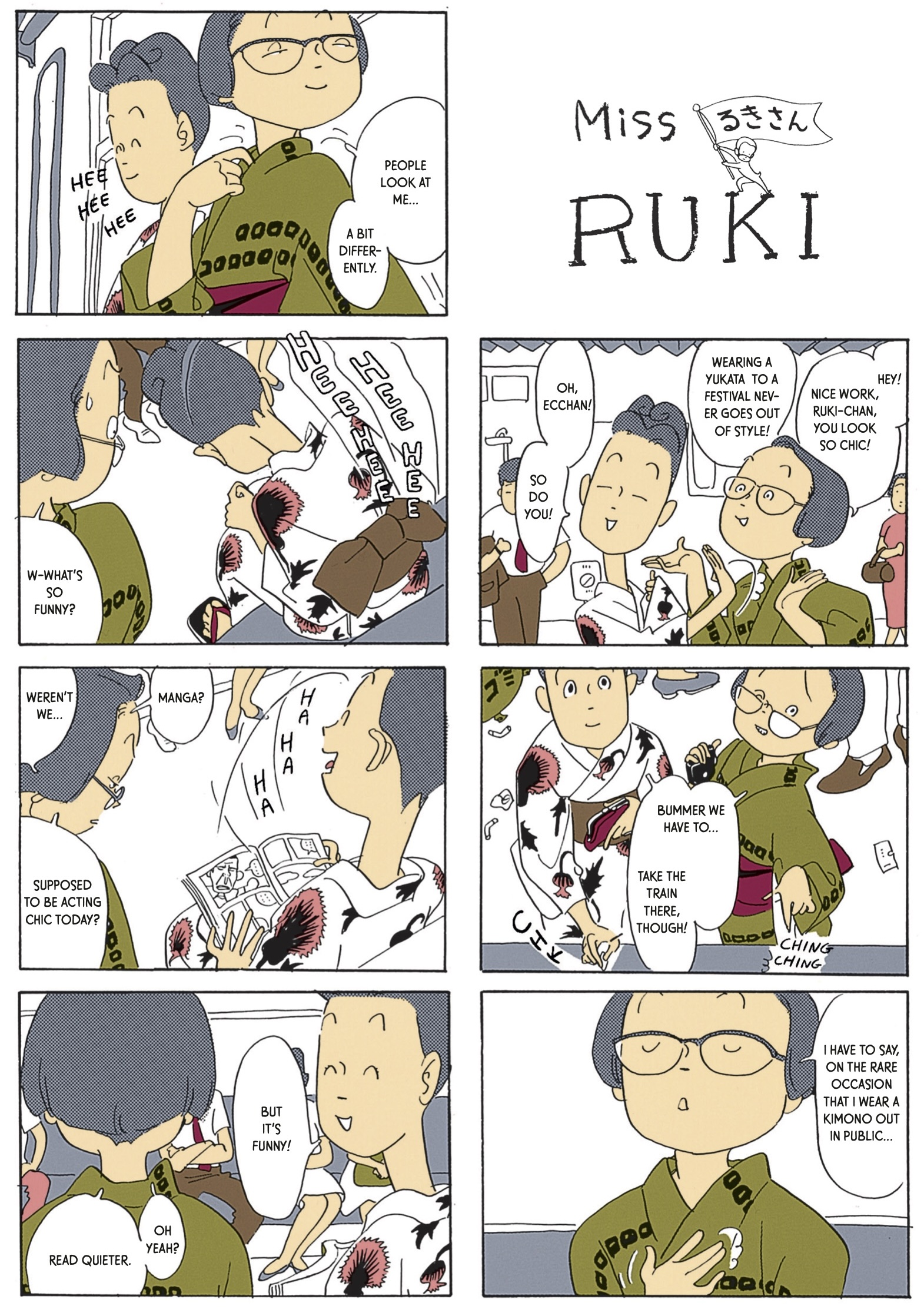

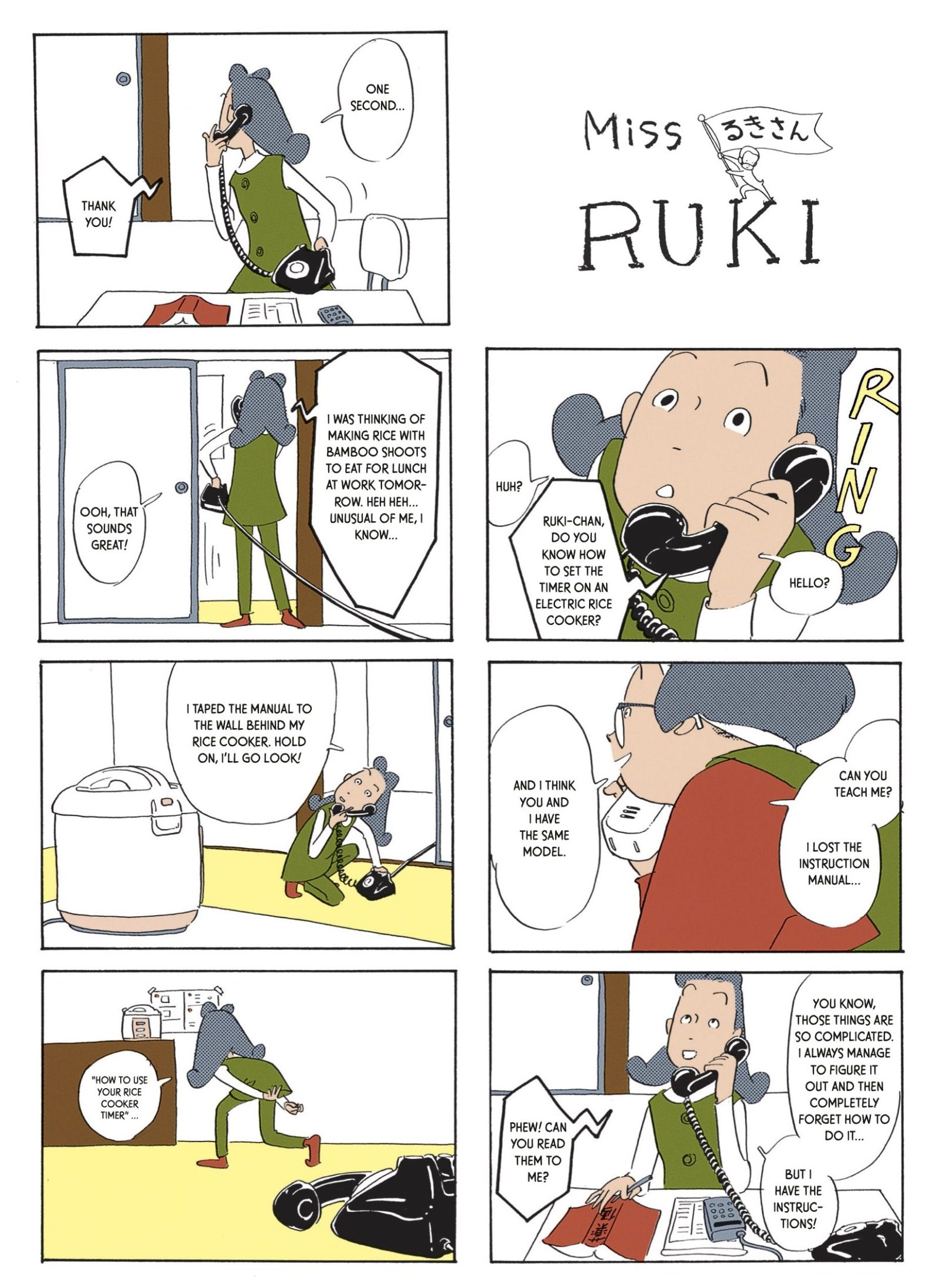

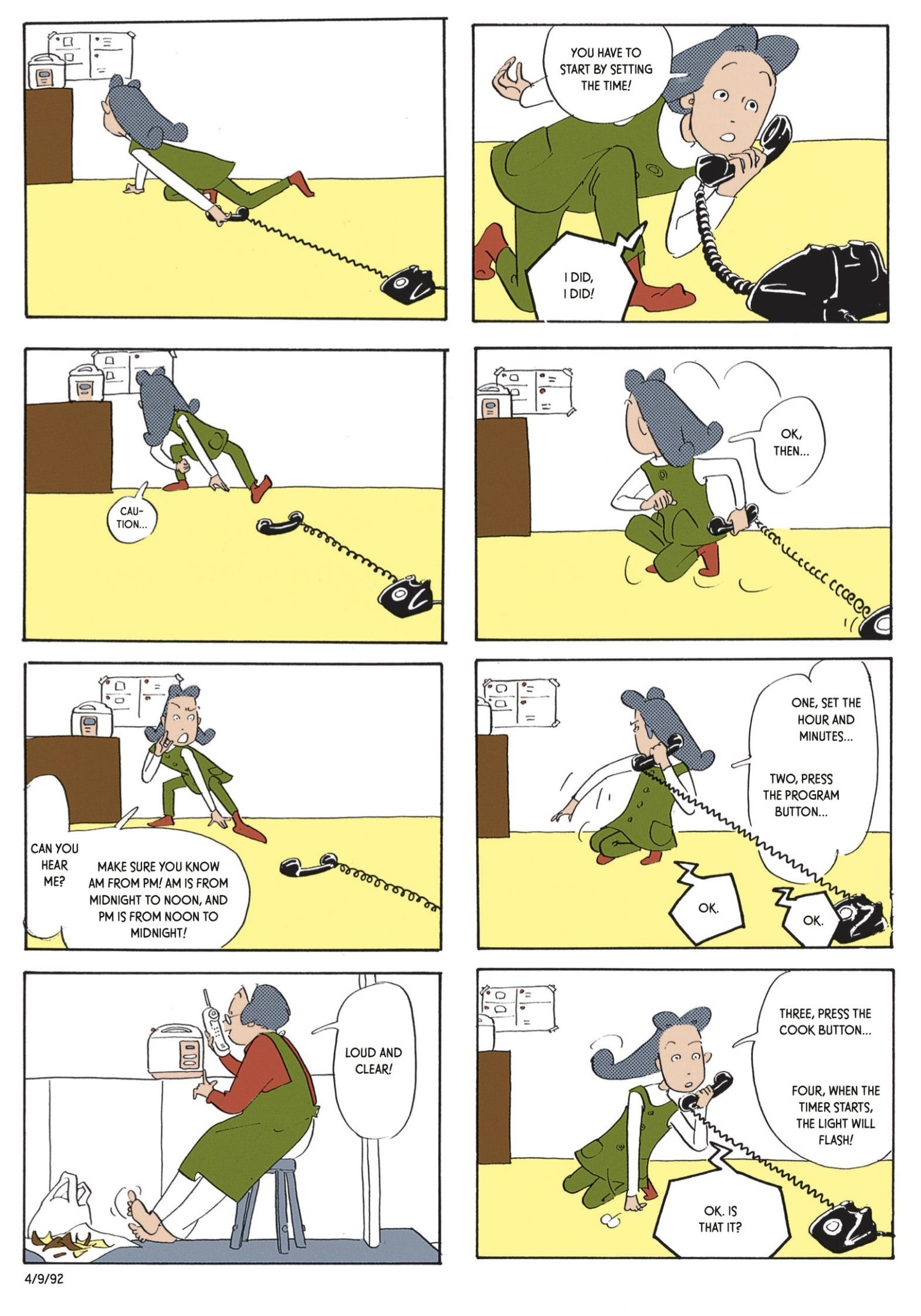

Note: All images begin with the upper right panel and follow vertically. Read right side dialogue first.

Note: All images begin with the upper right panel and follow vertically. Read right side dialogue first.Fumiko Takano is one of those artists who becomes everyone’s little secret. You stumble across one of her gorgeous, hard-to-find manga. You share it with a close friend. Before you know it, you’re both on the lookout for more.

But the hunt isn't easy. Takano’s books are seldom imported, and none are in English. Online coverage, scant as it is, only builds the suspense. First, the artist wins the coveted Tezuka Osamu Prize – Japan’s answer to the Eisner. Twelve years later, she claims the Iwaya Sazanami Literary Award, making her only the second managaka to receive this honor, after Tezuka himself.

Now at last, the wait’s over, the secret’s out. Fumiko Takano, manga poet and pioneer, has reached our shores. One of her most daring, delightful manga, acclaimed in Japan and Europe, is here, thanks to Alexa Frank’s sparkling translation of Miss Ruki, available from New York Review Comics on Sept. 16.

Imagine the faultless line of Hergé, combined with the elegant charades of Jacques Tati. Or marry the affectionate satires of Tove Jansson with the hilarious insights of Sempé, all through the lens of a manga master.

And not just manga. One thing you learn, seeking out her work, is how many Takanos there are. Like Joni, going from folk to jazz to oil painting, Fumiko Takano is always uncovering new facets of her muse. She'll win over the critics with her latest collection and despite that — or maybe because of it — devote years to learning a new medium for her next project: anime design, multimedia exhibits, or turning a Danish fairy tale into paper-cut sculptures.

None of these twists, however, prepare you for Miss Ruki. Over its four-year run, these 58 stories make up one of her most surprising — and subversive — manga.

In the late 1980s, the artist was invited to create a new series to launch Hanako, Tokyo’s leading women’s weekly. She accepted the assignment but, in a classic Takano turn, created a character who skewers the magazine instead. Issue after issue, Miss Ruki sends up the editors’ limited notion of a woman’s place in the world. The top brass might have been squirming, but readers loved it. This clearly autobiographical series uses Takano’s nimble humor to question Japanese society itself. And it’s something more besides — a searching, playful portrait of friendship, and freedom.

Golden snail

Though Fumiko Takano is a new name to many in North America, the list of her admirers is not. Katsuhiro Otomo (Akira) and Taiyo Matsumoto (Tekkonkinkreet) as well as more recent stars such as Keigo Shinzō (Tokyo Alien Bros.) praise her as an inspiration.

Another kindred spirit is Yuri Norstein, the giant of Russian animation. Hayao Miyazaki calls him “a great artist”, but he's better known by another name: the Golden Snail. The care and time this Moscow animator puts into each film means his viewers must wait years, and sometimes decades, between cartoons.

Fumiko Takano is no different. Across a professional life stretching nearly half a century, she's released just seven manga collections. These days, she'll put out a new book about once every dozen years. Since the last one came out in 2014, fans are hoping the Fates (or Fumiko) will soon smile on their patience.

But guessing this artist’s next move is rarely a safe bet. Like the title character of this book, Takano constantly breaks barriers by ignoring them. Born in 1957, she came up in the ‘70s zine movement. First as an amateur, then a prize-winning debutante, she drew highly personal stories in a unique, self-assured style. She was also unusual in choosing where she wanted those stories to appear. While no stranger to the young women readers of shōjo manga, Takano became a trailblazer, leading the way for female artists to publish outside those magazines.

With this book, we’re meeting Takano in the middle of her creative career. Yet even as she’s inventing Miss Ruki, her most popular and widely read manga, she’s moving beyond it, drawing the evocative, black-and-white set pieces that will fill Bō ga Ippon (One Little Finger) and later, the prize-winning Kiiroi Hon (Yellow Book).

In a sense, every manga she draws is a snapshot of where she is, and where she's heading — much like the dilemma she poses for two old acquaintances, meeting in Miss Ruki.

Gonna party like it’s 1989

As kids back in the countryside, Ruki and Ecchan (eh-chan) ran in different circles. When this book opens, seven years later, they’ve run into each other again. This time, they’re enjoying an independence their mothers could barely have imagined: single, employed, and living in their own digs. Along with millions of other young women in the late ‘80s, they’re in Tokyo, at the height of Japan’s prosperous bubble economy.

As adults now, are they interested in getting closer? Renting in the same neighborhood, they certainly live close by. So near, as the wonderful Japanese saying puts it, you could carry hot soup over without it getting cold. They stop by with other hot stuff, as well: gossip, delicacies, differences.

Lots of differences. To busy fashionista Ecchan, one thing's obvious already: Her free-spirited acquaintance is as clueless about guys, gowns and life in general as she was when they were kids. Deciding that Tokyo is Ruki’s last chance at style salvation, Ecchan takes the ignorant waif under her wing.

With that, the book’s off and running. As the two spar over fads and fashion, we join them exploring the capital. There are stories at parties, on bikes, and in the metro. There are shopping epics, bowls of udon and pots of tea, and a handful of bath cartoons, all gems, each one topping the last. (Of Ruki’s bathing, even her friend realizes it’s “part of some kind of ritual,” so best not to get involved.) These manga are such binge bait, don’t be surprised if you down this Japanese Jane Austen in one gulp.

Then, almost imperceptibly, on the third read, or maybe the fifth, counter melodies come into focus, just below the surface. Like some stereopticon trick, your perception goes from 2-D to 3 and you’re following these stories on several levels at once. More on that in a moment, but suffice it to say, this manga is lyrical, satirical and, though the topic barely gets a mention, sexy.

At first, Ecchan won’t so much as lick a postage stamp in front of her new acquaintance. But eventually, they’re teasing, tussling, and bribing each other for sleep-over privileges.

As the two become more attached, so do we, invited into their beds, their baths, all the intimacies and indignities of closeness.

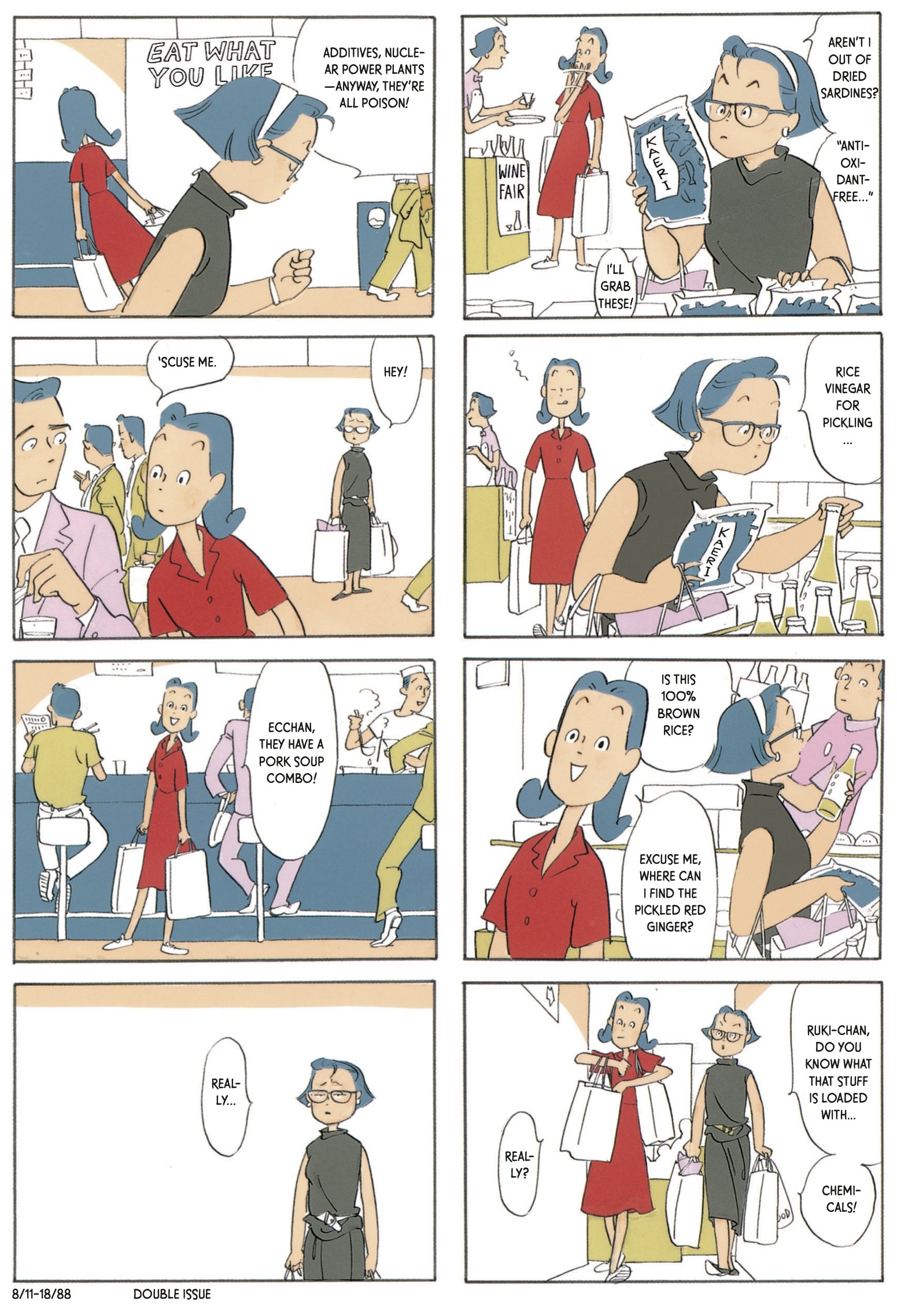

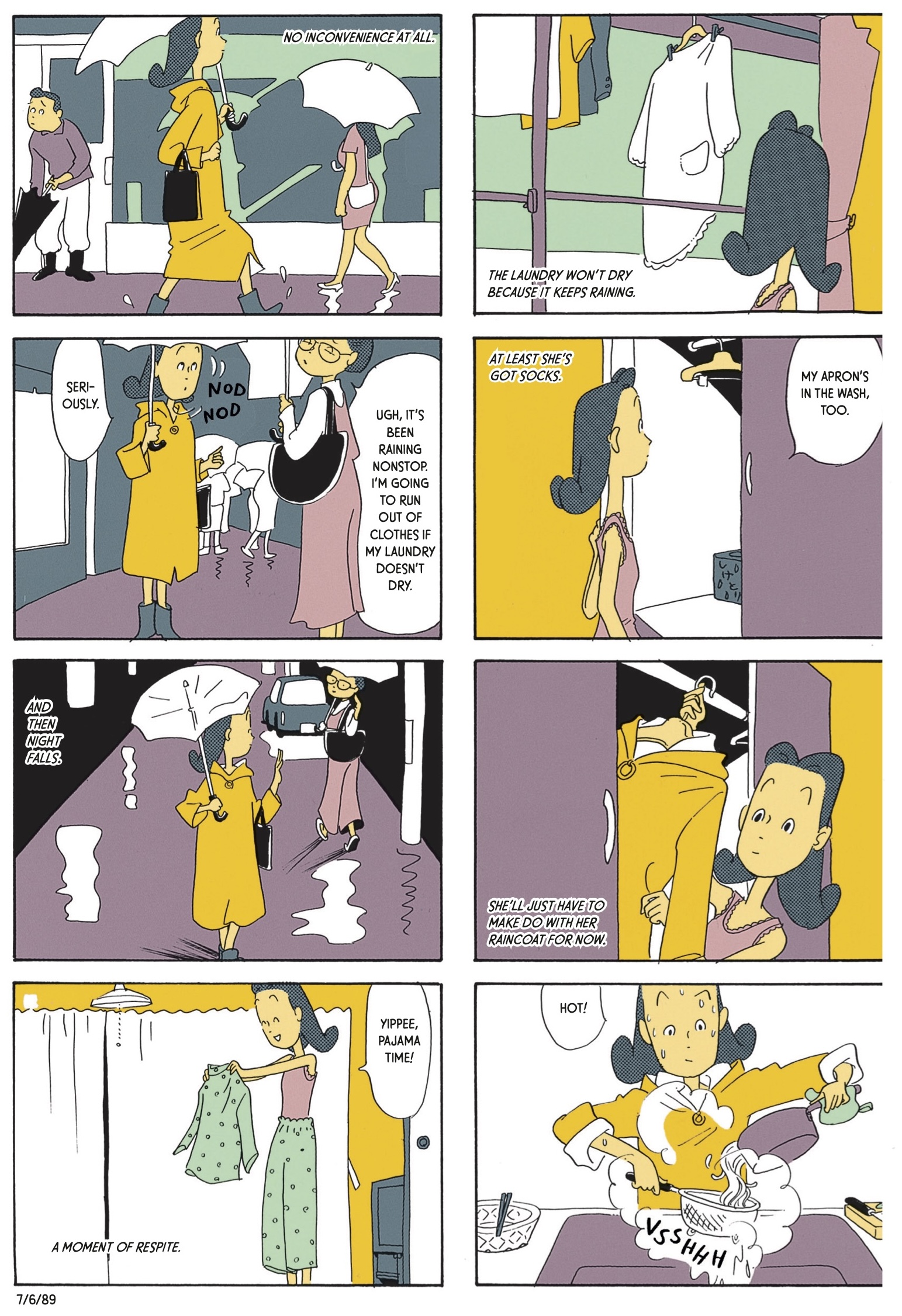

But sexiest is the series’ irrepressible joie de vivre. Is the bathtub your happy place? Then cram the entire apartment in there. Did every stitch you own get soaked out on the line? No problem, do the town anyway, wearing just galoshes and a raincoat. And while Ecchan falls to pieces over every handsome stranger, Ruki’s too busy making hot gyoza to notice hot guys.

So is Ruki gay? Absolutely, in a sense of that word we’ve all but forgotten how to use.

Ruki-chan

In Japanese, add “san” to a name to show respect, such as with Takano-san. End with “chan” instead, and it’s a mark of affection, as in Ruki-chan.

Whichever suffix you prefer, a lot of ink has been spilled in Japan, trying to figure Ruki out: What makes her so different? How did she get that way? And how does she get away with it? It’s anyone’s guess, since we’re given almost no backstory about our heroine, we don't have much to go on. For her part, Ruki doesn’t spend a moment on self-reflection. Well, except for one surprising sequence, when she speaks to the camera, addressing us directly.

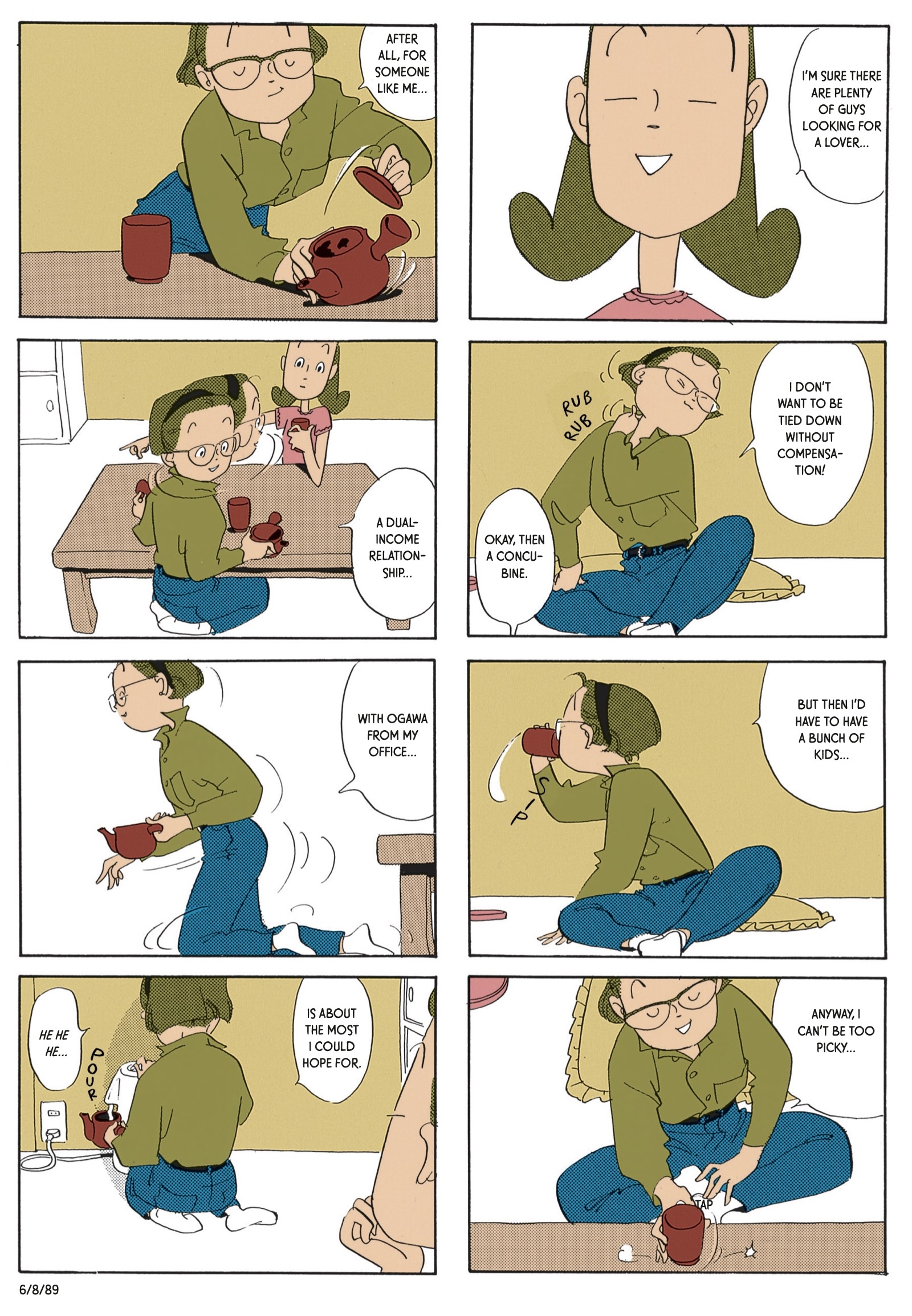

Other than that, she a lifestyle guru without a philosophy. An influencer who doesn't count followers. Ruki just is, defying gravity, and gravitas. But, like the rest of us, she does have to earn a living.

That's where it helps being a adding-machine whiz. As a freelancer, she carries home a month's worth of insurance claim forms to process. Four weeks later, she delivers the finished paperwork. Since her grateful boss never asks, Ruki doesn’t mention that she’s powered through thirty days of work in just seven.

With an envelope of cash in hand and three weeks off, the world’s her oyster, her eel, her artichoke – or whatever she fancies. What she does with her freedom, and how it contrasts with Ecchan's pursuit of the good life, is one of the delights of this series. In a snub to the cosmetics companies (whose ads paid for this manga in Hanako magazine) Ruki even refuses to obsess about her body, except the fingers that punch her calculator and the toes she nimbly uses to unplug it.

The few strips where Ruki is left on her own are different than the rest. Even the drawing style is simpler, sketchier. With no one to question her choices, Ruki goes rogue, indulging in daydreams that rival Little Nemo's.

Like one of those reveries, leaping off the page and onto my desktop, each time I type her name, the auto-correct on this computer changes "Ruki" to “Rubik’s”.

And a puzzle she is — to the kids at the library, the men who keep falling for her, the other passengers on the train and especially, to her friend Ecchan.

Ecchan

Leafing through this book for the first time, you’d be forgiven for thinking Ecchan’s the main character.

Clearly, she thinks so. Not out of vanity, mind you, but necessity. Without her, who’s gonna clue in Ruki about men, mood lighting and the other necessities?

There are many episodes where this is Ecchan’s book, the spotlight trained squarely on her. She makes good use of it, showing us tears and tirades that her beatific friend can't muster. Soon, like Donald eclipsing Mickey, and Haddock, Tintin, it’s Ecchan we more easily relate to, since she shares her every emotion with us.

Like the night she invites Ruki to her office Christmas party. Risking an early curtain on their relationship, Ecchan scolds and shushes Ruki all the way to the ball, unsure if her country-cuz neighbor will be presentable at the company HQ. But when they finally arrive, one of Ecchan’s junior employees walks right up to them. He asks to be introduced to Ruki. Why? Because, he informs her, Ecchan has been entertaining the whole office with “the best stories about you.”

Fatal besties’ betrayal? Hardly. For all her seeming innocence, Ruki has supreme self-confidence. She hardly notices when Ecchan chides her to her face, so why should she care if her friend’s entire workforce is laughing behind her back?

After this, familiarity breeds closeness, rather than contempt. Having weathered the party, the two are side by side the very next day, nursing Ecchan’s hangover. A few weeks later, they’re together once more, donning kimonos for the New Year.

This soon leads to a story, singled out in Frank’s excellent translator’s note, which is also a personal favorite. It starts with some juicy gossip: Ruki’s landlord has a mistress. Far from passing judgement, Ecchan wants to know if it’s still open season for sugar daddies like that.

What follows is one of the best portrayals in comics of two people getting to know each other. With touching nuance, Takano draws us into the personal ballet of these two, advancing and retreating with little signs, stretches, semaphore. If this were a love story, the artist would show us the usual succession of romantic milestones. But charting the almost invisible signs of a deepening friendship requires a different set of skills. This is one of Takano's gifts, a constant in her widely varying catalog.

This book is a master class in revealing character, rather than explaining it. Take one little pantomime, carefully set beneath the main action in this mistress episode. Ecchan is holding forth about her own romantic prospects. Unrelated to what she’s saying, we see her craning her head from side to side, while Ruki points across the room. In the next image, Ecchan is shuffling off in that direction, still talking about life and love. In the final shot, she’s refilling their pot of sencha.

What just happened? Takano has used an unspoken coda to let us in on a revealing moment – Ecchan has spent so little time in Ruki’s apartment, she doesn’t yet know where to find the electric kettle. In both women’s homes, this is heart and hearth, where the two will soon spend countless days to come, sharing tea and talk. But not yet – Ecchan is still finding her way there.

The book is rich in grace notes like this, cues to the subtle moments when a threshold is crossed, an in-joke born, slowly building to the kind of friendship where these two will burst in on each other without knocking.

Few of these occasions use words, which is one reason why translation software has been of so little help to Takano’s foreign fans. Miss Ruki is so layered, visual, and full of ‘80s references, with panels in which the shake of a head says more than the dialogue, Google and AI are out of their league. Instead, we readers-to-be had to wait for a translator as perceptive as Alexa Frank to come along and unlock this gorgeous manga.

Lost in scanlation

Some outstanding manga aren't released in English because their biggest fans give them away. For those new to the manga-verse, this is known as scanlation. Devotees will scan the pages of their favorite manga, replace the original Japanese with amateur translations, and post the results online for all to see.

The manga world is still debating the ethics of these self-styled Robin Hoods. But one thing is clear: few publishers will pay to professionally translate and print a book that readers can get for free.

The fact that only one of Takano’s works has been “liberated” in this fashion may be, in part, because so much of her storytelling is about what’s not said.

This also posed a challenge for Fulbright scholar Alexa Frank, the talent behind this English edition. “Whenever I read her work,” Frank told me, “I’m in awe of how she’s able to capture the most fleeting gestures and feelings. In our own lives, we hardly notice when we send these tiny signals. But to those who know us well, those moments are some of our most revealing.”

Finding words for these subtle exchanges wasn’t Frank’s only challenge. “There’s an infectious quality to the drawings,” she writes in her afterword, “that sometimes made translating a struggle.”

Like Takano-san, Frank is drawn to the widest variety of stories, translating everything from indie queer dramas to cat manga. (Yes, that’s a thing.) Interviewed in Asymptote, she explains her approach. “Translation, to me … feels very amorphous. I’m almost gliding over each panel and touching everything like a ghost.”

Across the range of books she translates, Frank works with admirable humility, letting the manga shine rather than calling attention to her contribution. Publishers don't always match her modesty. If their next release has a pulse and a few dozen pages, they’ll likely call it a graphic novel. But this book, Frank points out, fully lives up to that title. For all its high spirits, Miss Ruki is widely regarded as a work of literature.

Frank cites esteemed novelist Hiromi Kawakami. The author notes that, when it comes to capturing moments in the inner lives of women, Takano conveys through manga what writers struggle to express in text.

Frank goes further. Without abandoning graphic storytelling, she observes, “Takano’s work can transcend manga.” One example is the artist's unique use of color.

Only her hairdresser knows for sure

For all this book's literary qualities, Miss Ruki also deserves to be gobbled up like dessert. Sometimes it’s a Pavlova, light and luscious, no matter how often you come back for more. Other times, it’s a mille-feuille, challenging you to discern each layer.

There are so many, I’ll highlight just one. Takano is known for using every shade in her box of paints. But in Miss Ruki, she frees up color the way Herriman liberates landscape in Krazy Kat — changing the look of things from story to story, and sometimes, panel to panel.

Yet Takano pulls this off deftly, and the effect is something you feel more than see. The color combinations can be so ingenious, in service of the drama at hand, it took me years to notice that some of these stories are like manga on acid.

Take hair color. During the ennui of November, everyone’s hair is as grey as the weather. A month later, at the Christmas get together, each party goer sports a flaming orange ‘do. Come March, Ecchan has gone from bright to brunette, bawling over unworn outfits, swearing to change her free-spending ways. Weeks later, the only thing that’s changed is her hair. It’s green.

Does this Wizard of Oz hairdo distract us from the story line? No, we barely register it, since Takano has altered the shade of clothes, floors and else everything in the frame to highlight one thing – Ecchan's prized pink cardigan.

Leprechaun hair, Andy Warhol walls ... even Ruki’s apartment walls go from drab to dayglo, depending on what the artist wants our eyes to track in the foreground. In stories with flashbacks, changing hues differentiate past from present. Like learning a new word, once you discover this color aikido, it’s everywhere.

Fifth Beatle

If there’s another source of gravity, influencing the orbit of our central pair, it may be Godzilla’s playground, Tokyo. Like her two characters, Takano was raised in a small town. She uses these 58 stories to revel in the freedom of her adopted city. Never imagining that this manga would attract a global following, she indulges in hyper-local scenes and wordplay, with Tokyo references that even Japanese from other cities may not recognize. But like the Israel portrayed in Rutu Modan’s superb Exit Wounds, the Japan conjured here is so richly human, we soon recognize ourselves in it. The local, we discover, can feel universal, and '80s Japan, like last week.

Besides the capital city, another invisible hand at work in launching this series was Hanako magazine. Ecchan is repeatedly shown leafing through its pages, absorbing guidance on the latest clothes, trends and tech. But if she stands in as the ideal member of the Hanako tribe – as the magazine’s upwardly-mobile readers really were called – Ruki is their anti-matter. One wonders how advertisers liked sharing space with a manga that questioned the need for buying make-up, or even a mirror. And what did the management make of this series, gleefully biting the hand that fed it?

So if there is a fifth Beatle, it might actually be Takano’s husband. Put in charge of choosing manga artists for the new magazine, he nominated his wife. This wasn’t nepotism — Takano was already a rising star, familiar to Hanako readers from their shōjo-reading days. Still, it's hard not to think Fumiko Takano created Miss Ruki as a double insurrection, teasing not only her employer, but her husband. Both knew well enough what sort of free spirit they were unleashing.

Speaking of rebels, to understand the enduring appeal of Ruki and Ecchan, it's worth considering another indelible pair from the same years — Calvin and Hobbs. Though worlds apart in temperament and technique, the two strips trafficked in the same essential vitamin: Undermine the status quo by finding where it's ticklish.

It's been decades since either Takano or Bill Watterson drew their strips. Yet both are as popular as ever, and not just among those who remember when they were first published. Without movies, merch, or one fresh story to pull in new readers, legions of first-time fans keep digging up these treasures, and claiming them as their own. To see these characters skipping along, alive and kicking, look no further than the closest bulletin board, the newest reprint, and even tattoos, peeking out on arms and ankles.

Perhaps Keigo Shinzō (Tokyo Alien Bros.) best describes the latest cohort, discovering this masterpiece:

Miss Ruki is a manga that I’ll always keep in the most precious corner of my library. To read it is to grasp something of the essence of Japan. These divine angles, these elegant colors, this lightness that Miss Ruki has in her way of life. This work drawn 35 years ago hasn’t aged an inch. It is too universal to ever go out of style.

Wait, did I say, the latest cohort? Shinzō and friends, please pass the torch. There’s another crowd eagerly waiting — in America, Australia, England and beyond, ready for their chance, at long last, to take on Tokyo with Ruki and Ecchan.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·