Thomas Campbell | August 27, 2025

Cameron Arthur may be a new name to a lot of readers. He’s a Texas based cartoonist that splits his time in Pittsburgh, PA with veteran cartoonist, friend and mentor Frank Santoro. Arthur has gotten a bit of attention in recent years in certain comics circles for his self-published series, Swag – some of which is republished in this collection. The series consists mostly of taut short stories drawn in a barebones style. His work places a strong emphasis on quiet storytelling and human drama focusing on the buildup and aftermath of dramatic events. His drawing is stripped down and utilitarian almost to the point of being void of style. Paradoxically that becomes his signature style. The approach allows the flourishes that he does employ some additional gravity. The stories in Hidden Islands were drawn over several years and Arthur’s evolution as an artist is evident. Notably, Arthur does not post his work on any social media and doesn’t have an online storefront. Word of mouth has been the way to find his work, and emailing the cartoonist to see what’s in stock the way to obtain it. That’s changed now with the wider but decidedly still DIY release of Hidden Islands, Cameron Arthur’s debut collection from Bubbles. Following in the path of Bubbles’ previously released short story collection Stories From Zoo by Aanand this book offers a spotlight on a rising talent in literary comics.

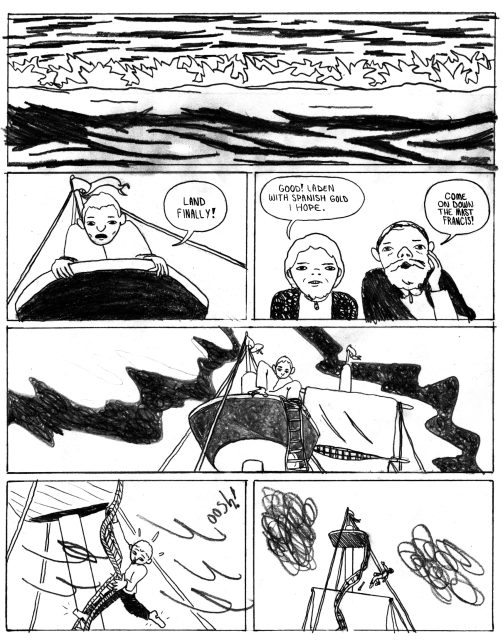

page from Hidden Islands by Cameron Arthur

page from Hidden Islands by Cameron ArthurIn the titular story Hidden Islands an unnamed man takes a job delivering supplies to an isolated community by boat. The people live alone or with their families in small homes off a forested river. The river is drawn beautifully with dark swirls flowing across the page. It’s a striking contrast to the thin lines used for the backgrounds and characters. This brisk story is shrouded in mystery. Questions arise and remain unanswered as packages are dropped off to the denizens of this remote community. What are they doing here? What are they escaping from or seeking out? The reader is kept in the mystery as much as the characters. The longest stop on the courier’s route finds him mixed up in family drama involving a carefully delineated dead wild hog. Dinner. The boatman says seeing the porcine beast is the first time he fears nature. Death can be frightening, but it’s being viscerally confronted with the social death the hog represents that is the true horror. The previous courier is described as a nut, but being on an island adrift on this monotonous task may have caused his insanity. The theme of isolated individuals, hidden islands, is one that Cameron returns to throughout the collection.

The maritime setting continues in the next offering, Waiting Treasure. A small band of pirates, men with hopes and delusions and not much else, sail to Tejas off the Gulf of Mexico in search of a rumored buried treasure. Degraded from earlier myths of a city of gold, their modest aim for ill-gotten gains is merely a buried chest of gold. Stylistically here Cameron leans more into the smudgy graphite of his pencil drawing – the pencil residue reflecting the dust and sand of roughing it on a sailing ship. It’s a futile trip, however, and few hold out hope as the odds stack against them. The captain, whether craven or loyal, stays on board with a dying man as the rest of the small crew venture ashore. There’s whispers of mutiny as the realities of this quest become clear to the men. They are living in a post-Colonial world searching for Spanish gold. They know deep down that they won’t find what they’re looking for. The myths of yore were at least grand and driven by chivalrous duty. This incarnation of seafarers are just mercenaries– willing to abandon each other and their goal when reality sinks in. It's an effective anticlimax as this doomed trip fizzles out. Each pirate slowly accepts their fate, while the captain holds on. This story allows Cameron’s prose to shine: “A seaman shouldn’t drown while still on the boat. Unless he’s going down with his ship of course. And a captain must treat his crew like it’s part of his ship. Therefore I mustn’t let you go down. Otherwise me and the crew might join you” the captain opines to a dying man across a spread.

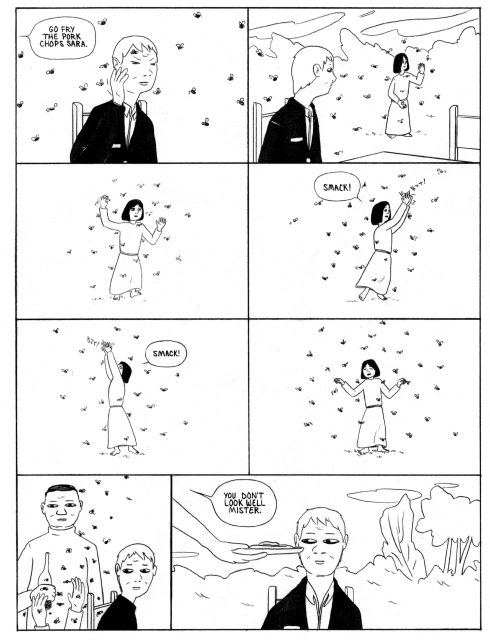

page from Hidden Islands by Cameron Arthur

page from Hidden Islands by Cameron ArthurIn Silent Fields we see the western trope of a mysterious stranger passing through. This is another story of living an isolated life. This time in a flat western landscape during the 1860s. Arthur adopts another variation on his drawing style, opting for a thick consistent line weight. A stoic style. Silent Fields finds a mother staying strong while awaiting her husbands’ return from the war that unbeknownst to her ended a year and a half ago. She’s a hardy figure as she handles household chores and looks after her son and his only companion, a chicken named Clucky. Arthur leans into his chosen style here to reflect the inner lives of these characters. Often seen in profile with minimal facial expressions, his line conveys the stiff upper lip demeanor of an isolated life on the frontier. It’s a difficult life, but not quite dire. Again here we see people living after the fact. The boom has ended. So when a man wanders onto the property Lola and his son take a leap of faith in trusting him. Given the circumstances, she is left with few options. There’s undertones of romance between the two lonely figures as they share time together, but both are dedicated to something else. Lola, to her husband; and the traveler to his journey. The mother’s trust is karmically rewarded when, after going missing, Clucky the old hen fills a hole in the ground with enough eggs to feed the family for weeks. It’s a hopeful story, but one tempered by low aims of subsistence. The best one can hope for in the stories in this collection. Again here we see Cameron hits that placid tone. The highs aren’t too high and the lows aren’t too low. These are just another set of islands.

In what is the most visually interesting story of the book, a would-be graverobber prowls a cemetery at night assisted by an inquisitive orphan. He’s a desperate man looking to steal a body part to pass off as a religious relic to parlay into a fortune that will help him woo a prominent woman in town. If that sound convoluted, it's supposed to be. Like the treasure hunters from earlier, this man is grasping out at any means of upward mobility. This strip is more claustrophobic than the other stories in Hidden Islands, dense with panels and looser, scratchy drawing. It’s a story that wouldn’t be out of place in an early issue of Crickets or as one of CF’s more grounded efforts. There’s a viciousness to False Relics that we don’t see in the other stories. It’s a portrait of one of Arthur’s characters pushed past their breaking point. Making one last desperate bid. Where his other protagonists still hold on hope, the graverobber is reckless and cruel. It’s what lies beneath when the stoic mask slips.

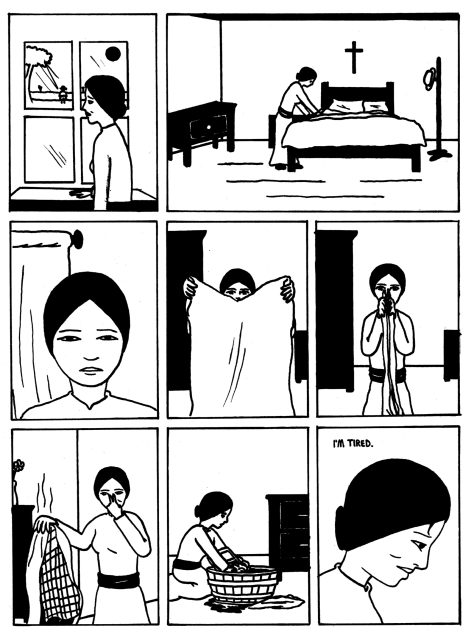

page from Hidden Islands by Cameron Arthur

page from Hidden Islands by Cameron ArthurThe final story in Hidden Islands, Night, is about a small family reunion where the adult children and their romantic partners are back under the same roof after an extended time. This is some of Arthur’s finest storytelling, but highlights some of the shortcomings of his drawing. The story shifts perspectives juggling the inner lives of the “kids” and their parents. It's a night soaked in booze for some, a celebration for others, and a stark call to reality for a few. Characters are drawn deftly, tension barely kept under the surface. Like the best of his work, Night has a strong vision and mostly pulls it off. There’s themes of alcoholism being passed down, refusing to leave the nest, and sticking with a relationship past its due date. Night is novelistic in scope, but highlights Arthur’s tendency toward restraint and leanness. This could easily have been his Bottomless Belly Button. But where Dash Shaw’s debut luxuriated in long decompressed sequences, the approach here is to infuse every panel, every line of dialogue with text and subtext. It’s a story that requires rereading, if not only because characters can run together in the way they're drawn, but because of the rich interplay of their connections. Night captures the complex family dynamics that resurface when you spend an evening back together. It's also some of the least visually interesting comics in the collection. Many backgrounds are blank. The subtleties in expression seen in earlier stories isn’t as developed here, and there’s wonky perspective and proportions at times. None of this is disqualifying of course. In fact it's quite interesting to see Cameron’s chops at different stages, and the way he employs style to different ends for the recurring themes of the stories.

The throughline for the book is a cartoonist working in a uniquely literary vein. As a storyteller Cameron focuses on spaces between. The drama and action happen off page, the reader is privy to the build up and the aftermath. Throughout Hidden Islands he sketches out characters who have missed their shot or never had a shot in the first place and societies past their prime. His storytelling is lean. Everything here matters and it’s defiantly not flashy. Subtle eye movements, underplayed “acting,” and variations on style show an artist experimenting and taking risks. Those risks don’t always completely pay off but when they do, they pay in dividends.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·