John Kelly | January 19, 2026

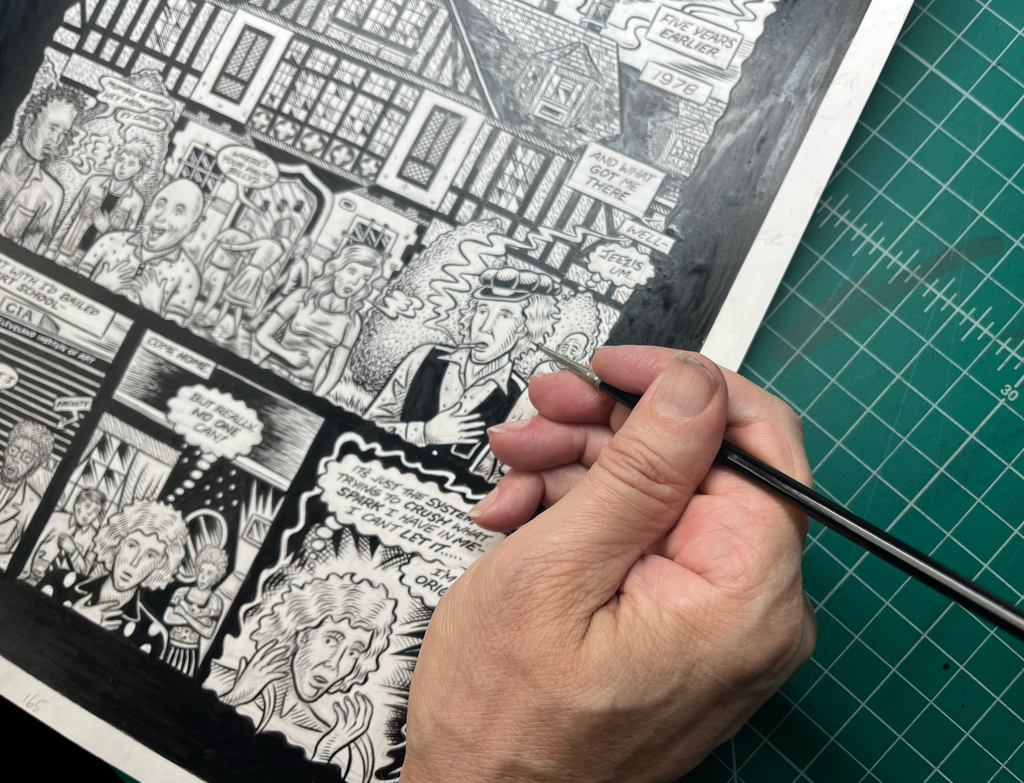

Glenn Head in his Brooklyn home, holding a page from his upcoming memoir Asylum (Fantagraphics). Photo courtesy Glenn Head.

Glenn Head in his Brooklyn home, holding a page from his upcoming memoir Asylum (Fantagraphics). Photo courtesy Glenn Head.Of all the cartoonists emerging during the 1980s, Glenn Head seemed to be the one most closely channeling the frenetic zeitgeist found on the pages of some of his beloved comics of the underground era. Read today, his early, wild, "true life" stories chronicling the New York he was living in at the time are a reminder that the city could be a scary place indeed. New York in the '80s could be extremely exciting. And very dangerous. Depending where you were at the time, one wrong turn could find you on a block that ... you shouldn't be on. And as a reporter, whose beat was his own life, Glenn told stories inhabited by his neighbors — drug dealers, corrupt landlords, call girls, and addicts. These early autobiographical comics were authentic accounts of life in certain neighborhoods in New York's Lower East Side and Williamsburg, back when Williamsburg was ... well, not what it is today. Some of this work was captured in his 1987 self-published Avenue D (later expanded and reprinted by Fantagraphics in 1991). The strips had plenty of booze, drugs and sleaze, but he certainly didn't glamorize it. As someone who walked those same streets at that time, I still find them to be accurate. And I really loved them. It turns out that this material was just setting the table for Glenn's stunning, mature memoir work that would emerge decades later.

His first book, Chicago (Fantagraphics, 2015) tells the story of teenage Glenn dropping out of art school to hit the road in search of his underground comix heroes and fame; along the way, fate has other ideas. It's as fine a first memoir as I can imagine. And he was only getting started. Chartwell Manor (Fantagraphics, 2021) came next and that book is something else altogether. It chronicles the abuse he encountered during his early years while attending a hellhole of a private boarding school run by a deviant psychopath and sexual predator. It is a story that is, in very many ways, unsettling and, ultimately, sobering. He is currently finishing his third memoir, Asylum, and in the interview below we discuss its contents and his process. Among many, many other things. All three books explore his early life and transformation into the master storyteller he is today. They recount his successes and struggles, some of which were self-imposed. At times the stories are comical and at others they are extremely harrowing. And they are always honest. Brutally so.

This is a wide-ranging interview that covers the entire arc of Glenn's life and career and was conducted in several sessions over the course of the past several years. Back in 2022, Tammi Morton-Kelly and I visited Glenn at his home in Brooklyn, N.Y., and while there we eagerly examined the early pages of Asylum. After an extended break, Glenn and I reconnected via Zoom to fill in some blanks and explore additional lines of inquiry. This resulted in many, many hours of conversation and the interview below was transcribed by Tammi, which was no small task. In the initial session, she made an observation about how Glenn handles trauma in his work, which leads us into a brief discussion about empathy, which, for Glenn, is a key to a successful memoir. Glenn and I would also like to thank Xeni Fragakis for her assistance with the editing of this interview.

In a 2022 Comics Journal piece I wrote about the death of Justin Green, who set the bar for autobiographical comics, Glenn said the following: "Justin's work was shocking because it went deep into his own traumas, rather than attempting to inflict them on the reader."

He could have easily been talking about himself.

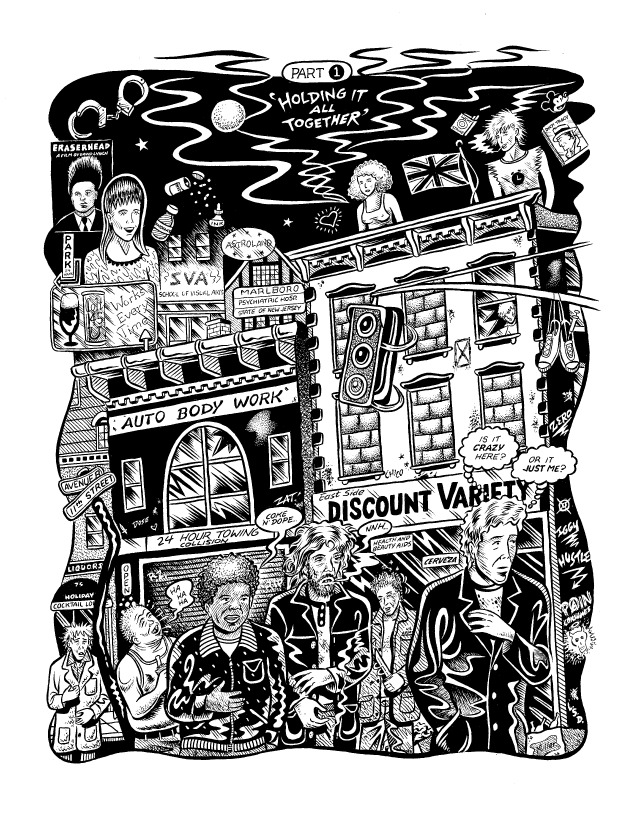

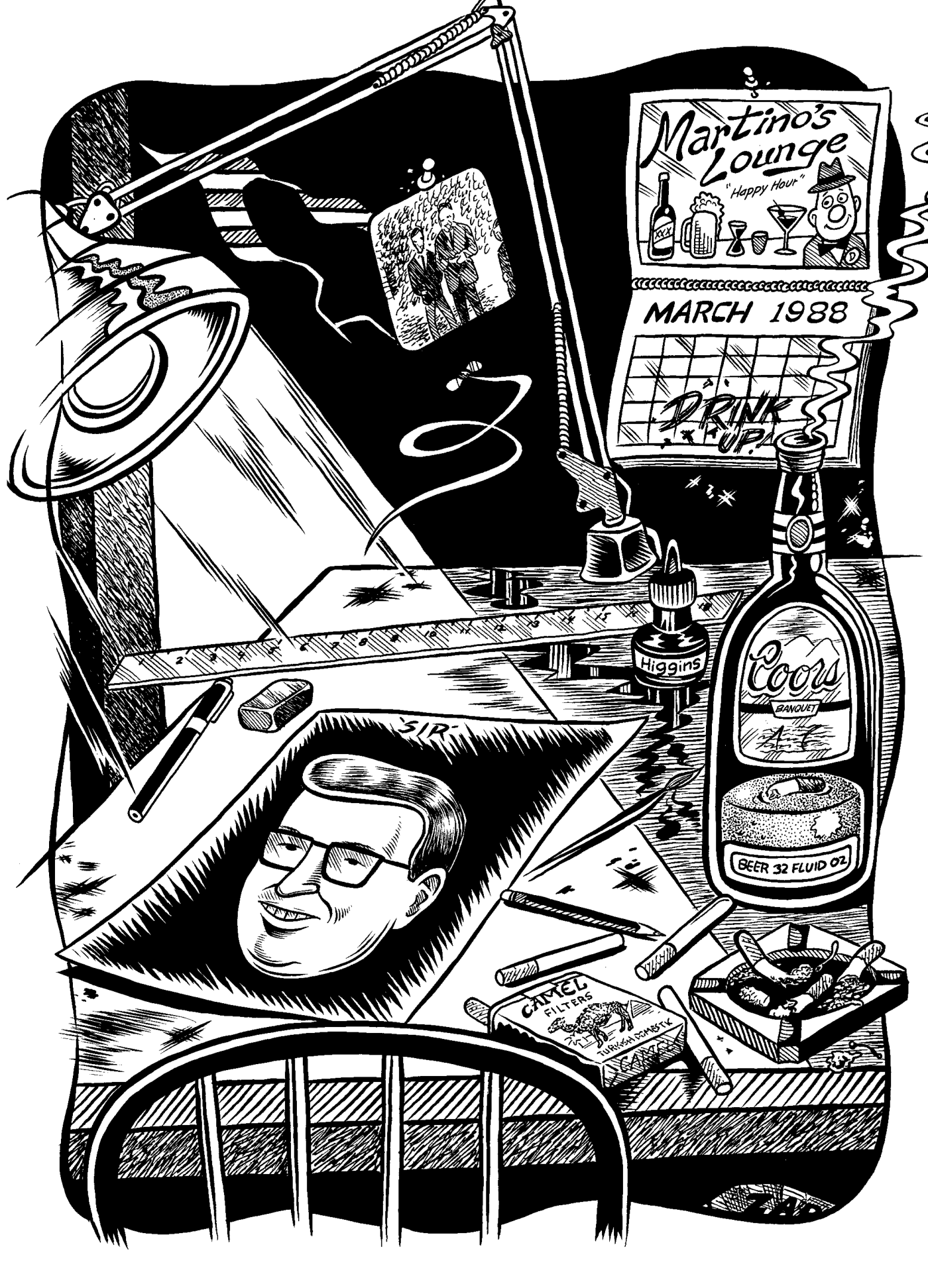

A page from Asylum. Courtesy Glenn Head.

A page from Asylum. Courtesy Glenn Head.JOHN KELLY: With a lot of my favorite artists, it seems like their target audience is ... themselves. There doesn't seem to be very much calculation over whether something will sell a lot of copies or be particularly popular. The pure motive to make it is that's just something they want to make.

GLENN HEAD: Yeah. This is my experience too.

So, with autobiographical comics — and I'm just talking about your own work now — I can't imagine that you go into that genre thinking, "Well, it's got to have this, and that, and this too," in order to be "sellable." Whereas so many other "popular" creators are likely taking into account countless standardized elements when they are creating their stories because they're producing ...

Entertainment.

Yeah, right. So whatever particular "thing" is marketable, at any given moment, can be what drives the work.

Exactly, exactly. Trying to find all the right ingredients.

Right. But the best memoirs seems to come from some deeper need to get that story out because it has to be told. When you're telling your own story, you can't really plug in elements in a calculated way in order to cross them off the "must have" list. Something either happened or it didn't. Unless you're making it all up, which is not unheard of.

I don't know how anyone could do that, frankly. I mean, that's what kills it. If you look at any really good autobiography, the key is always a matter of vulnerability. So you have to drop your guard and show yourself or it's not going to work. Your weaknesses, perhaps, maybe things that terrified you.

There’s a George Orwell quote that I like a lot. "Autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful." Like with Justin Green or Joe Matt. Because that's not the kind of shit you make up; that you masturbate too much or that Catholic guilt is eating you alive. I mean, why would you? So that's when you can trust it. You know what I mean? When somebody's trying to make themselves look good in autobiography, that really kills it. It's just not what we want from it.

And so when you read a memoir or autobiography, you want to see what's not being shown. That's the reason for its value to people, I would assume. You want to see the id!

Right.

I've had a real background in a lot of different kinds of comics, so I feel like I've learned how to apply what I've learned in genre comics, whether it's funny animals or stuff like that. One artist who inspired my early work was Kim Deitch, from whom I learned it’s always about story, trimming the fat, making it read. Genre stuff is really good for that, too. Beginning, middle, and end. The same goes with autobiography. It’s personal, but it’s got to be entertaining, too. So you apply those rules. Just because something’s happened doesn’t make it intrinsically interesting.

Right, right. But there have been some autobiographical works that have been popular where it later turns out that a lot, or at least some of it, was fabricated, right?

Oh, there's been a lot of bullshitters in the memoir game, from James Frey to other people. It happens pretty regularly. And nearly always when you read that stuff, it doesn't sit right. It's not believable. Like James Frey wrote this book, A Million Little Pieces, and a lot of it takes place where he's in rehab and he's hanging out with tough guys and he's a tough guy. And the worst thing you can be is a fake "tough guy," because it isn't really believable. People can really sniff out the falseness with this stuff. And so he wasn't able to get away with it.

I think there are things you can do in autobiography that may not be 100 percent accurate. I think there's other things where you can ... you can kind of integrate things that happened with different people into one person and make it work for the sake of the story if it's not crucial. But if it's essential to the story and you're making it up, you're really going to shoot yourself in the foot. You know what I mean?

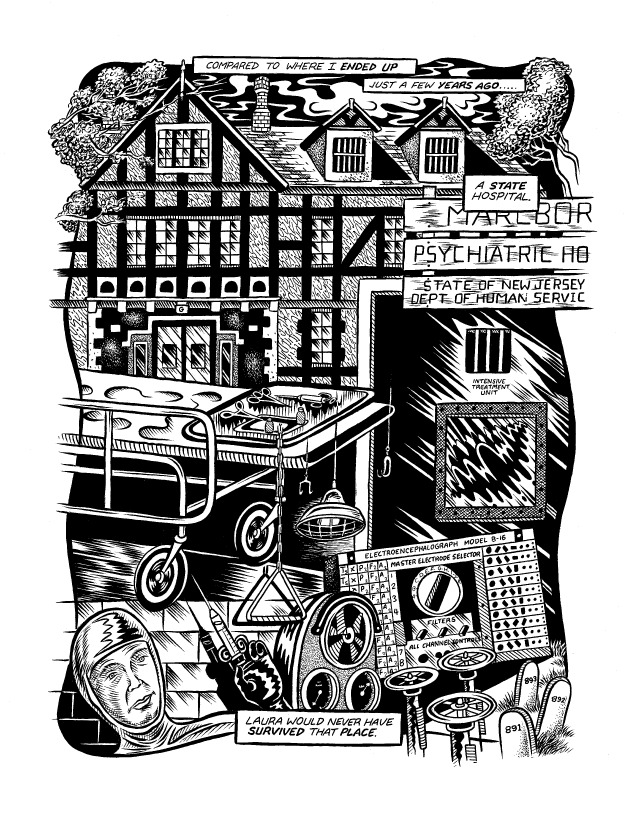

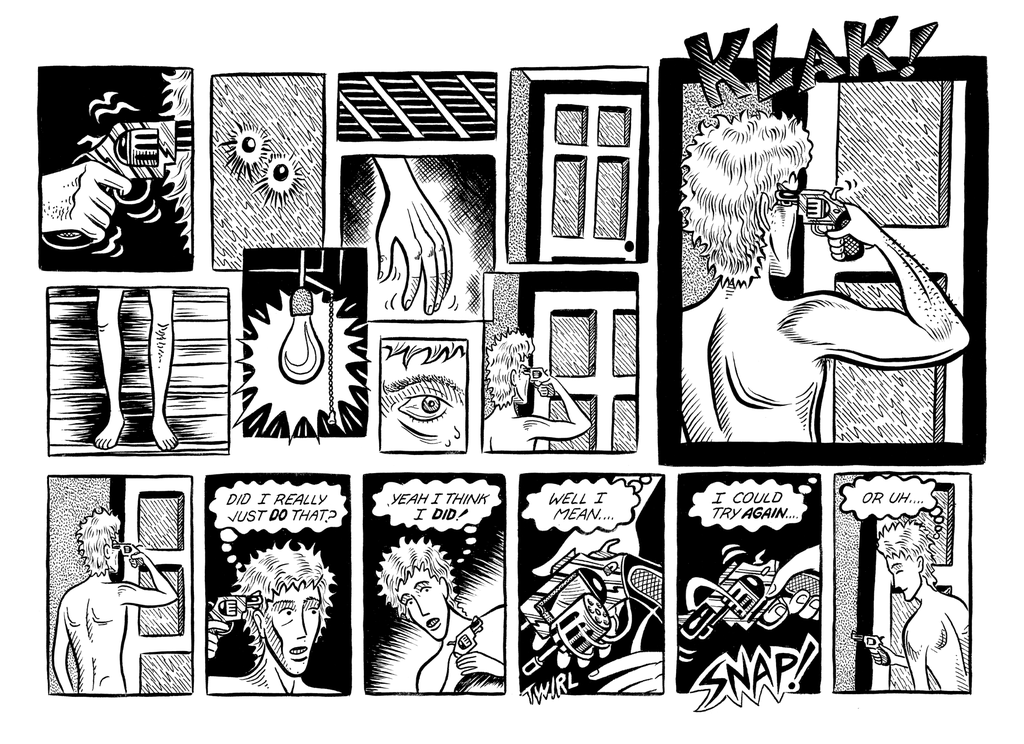

But there are certain things that really do have to be accurate. You know, like … the new book that I'm working on, Asylum ... there's 20 pages of me locked up in a mental hospital. If I made that up, it would be for shit. You know, it just wouldn't work. And there's also a scene where there's an assault with some policemen that I'm dealing with. I just try to draw it as accurately as possible and trust that it’ll communicate.

But there’s also stuff that happened around the same time in my life that I wanted to include but realized that those things didn’t serve the narrative, that they were distractions. It was hard to let some of that go. There was a lot of stuff about Keith Richards and Brian Jones — there's still some stuff about Brian Jones — and my wife was like, "Does this book really need that much Rolling Stones?"

It was my wife, actually, who helped me figure out what I was trying to say, how to sort of take the block that is my life and carve away the non-essential parts and leave the parts that tell the story I want to tell. Fiction writers are more like painters, they can keep adding more and more paint, but the nonfiction writer is more like a sculptor, trying to give shape to the block they've got.

Another page from Asylum. Courtesy Glenn Head.

Another page from Asylum. Courtesy Glenn Head.So with Asylum, as you mentioned, there's a longish section about time that you spent in a mental institution ...

That's right.

... and another key point of the story is dealing with the death of a friend of yours, a guy who was from England.

That's right. He was a British expat who came over here and he's sort of the live-wire character that upends everyone's life. And he's in the story in the first part of the book. He was working off the books, and he was a really dynamic figure and character and a little bit of a mixed bag. Not necessarily a good guy, but he was my best friend, and he dies in a construction accident. So a lot of it is a meditation on things of this sort because there's a lot of human frailty in the book on my part and some other people, some family stuff for instance, that's also in the book.

And it's a question of luck: who survives, who makes it, why do we? And often there's no reason at all. There was no reason for Rupert to die at the age of 21 — he just turned 21 — but bad luck. He took a construction job that somebody else had offered him, and he needed the money. And he took it. And then he died. And that was that.

As a character, Rupert was really interesting in that he was one of the most invulnerable people I'd known, seemingly invincible, so it was so was the last thing you would have expected, and yet it happened.

The title Asylum, though ... I mean, "asylum" can refer to a number of different things, right? When I initially heard that that was the title for the book I thought, oh, well, okay, so a character who's an expat can be seeking asylum, but I also know your personal history. So there could be a couple of different things that you could read into that.

Right, right. That is in there too. Asylum is a safe place, and that's what my sister who had mental and emotional problems and schizophrenia was also looking for. For Rupert, it was also asylum, but of a different kind than the usual kind. Rupert was actually not unlike a lot of people who come over to this country illegally, without a green card, and are looking for a better life. It's just that in England — to come to America from England, you pretty much had the world by the balls, especially if you were a good looking guy with a good sense of style and you're in New York and you're going to all the hip clubs. Everybody loves you. But it was still a thing of "asylum" where he needed to work. He needed to be here as opposed to England because there wasn't any work there. There wasn't any money to be made. It also connects to that.

But of course, the obvious connection is a mental asylum where you end up because everything else isn't so good, you know, and in my particular case I was a bit crazy. And anybody who's ever been crazy will tell you, I wasn't as crazy as them. But there I was, in this place as a result of this altercation with some cops. So, yeah, that's where I was for like six weeks.

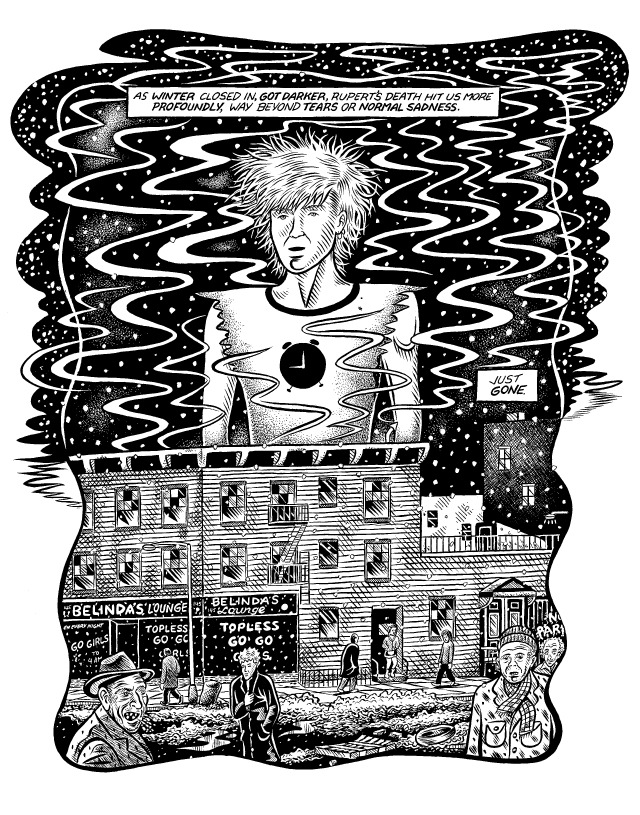

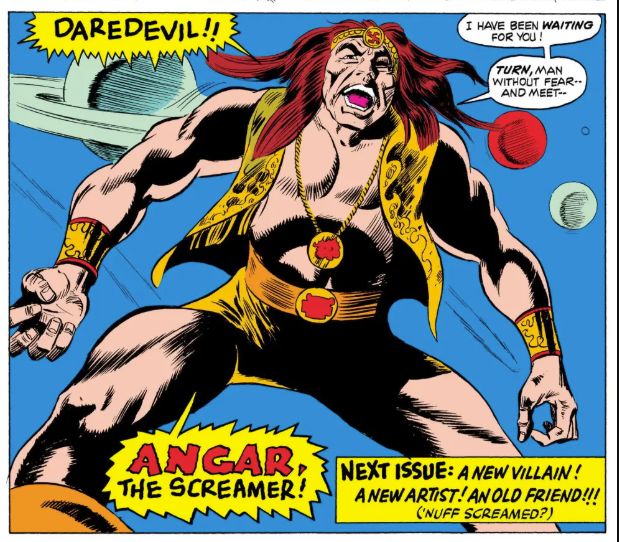

Chester (Glenn) meets Rupert in the story "Random Factor" from Glenn's 1996 collection GUTTERSNIPE #2.

Chester (Glenn) meets Rupert in the story "Random Factor" from Glenn's 1996 collection GUTTERSNIPE #2.Now, the Rupert story was first introduced in an earlier comics anthology, GUTTERSNIPE #2, in the mid-1990s. The story is called "Random Factor," and it introduces some of the themes that you're exploring deeper in Asylum — randomness, luck, the seediness of New York City at that particular time ...

That's right. Yeah.

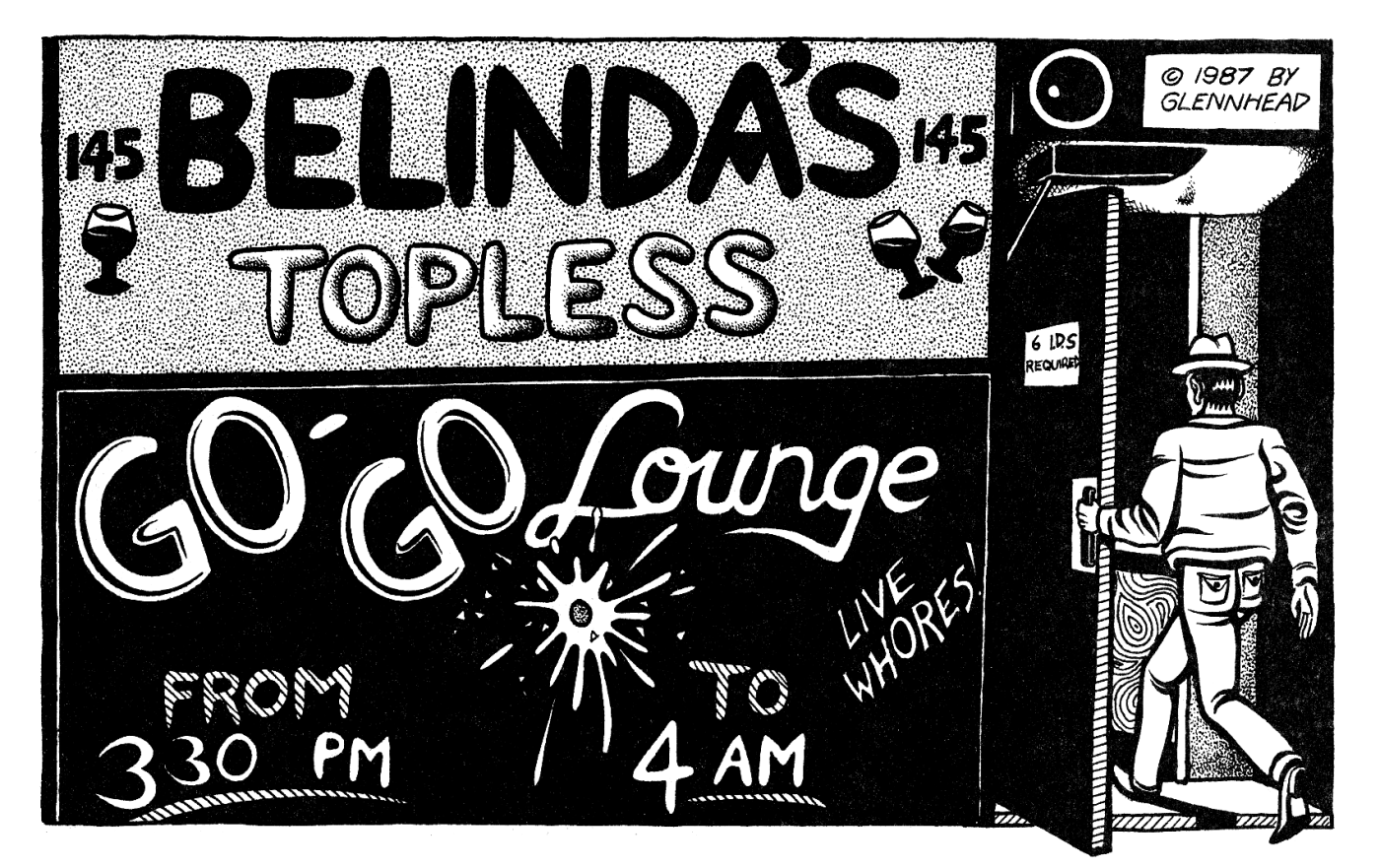

Glenn used to live above Belinda's, a Go-Go Bar in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. A number of his earlier stories took place in that neighborhood. Image courtesy of Glenn Head.

Glenn used to live above Belinda's, a Go-Go Bar in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. A number of his earlier stories took place in that neighborhood. Image courtesy of Glenn Head.That was a much shorter story that really just mentions Rupert's death. And at the time, you were living above Belinda's [a now closed topless bar in Brooklyn] ...

Yeah, that's where we found out that he was dead. This is one of the great things about the graphic novel, that part of the content can be time itself, and also the depth of character. So, like a big part of Asylum, the first part of it, is just knowing Rupert and showing him take me out of myself, and what that friendship was about. Whereas in the earlier story that you're referring to, it's almost like I was only able to introduce him to the story before killing him off. You know what I mean? So it showed just a couple of sides to him, whereas Asylum is really about relationships. That's what's really important to me, to try to put across how people get along, how they feel for each other, and the ambivalences that we can feel about people because Rupert had some kind of ... I guess I'd say quasi-fascistic sides to him that I am mixed about. And it was important to me to be able to show that in the book, that feeling of ambivalence about somebody who's your best friend. You know, we were close for a couple of years, and then to have that taken away is then very striking — to have somebody who's here with you all the time and then suddenly just gone. It's very unusual. It's not the way we usually know things to be, whether it's a parent or a grandparent or somebody who's ill, and then they eventually leave us. This just happened in the space of a day. Suddenly he was gone, you know?

Yeah, but you recognized a long time ago that there was something about that story that was worth telling and it's something that you went back to in much more depth. And that's part of what you do in Asylum.

Right. I mean, I really believe that with autobiography and memoir, for me, the things that affect us profoundly are probably our best material because they're going to want to be told. The things that happen to me on a daily basis, unless they connect to something profound, I'm not really all that interested in. And losing a best friend is going to affect one pretty profoundly. And likewise, so is being in a mental hospital, and this is the first time I've done anything with that material. That also really affected me. In a sense, it was kind of transformative because … one of the characters in there, who's sort of a counterpoint to Rupert, is my friend at this hospital, Conrad, who seems to be kind of a visionary and a very interesting fellow who, I found out later, died about a year after that. So that's the other counterpoint to Rupert.

To be in a hospital like that, at least from my experience, is to see the world through a different lens because, basically, most of the time in life, we're dealing with an agreed upon reality. You know what I mean? If I walk across the street without looking both ways, I might get killed, for instance. And these are the things that don't necessarily enter in the same way if you're hospitalized. All these people are really in their own worlds, with their own theories, their own visions of what life is, what it has to be. They're also on a lot of medication. But they're not dealing with reality in the way that we all normally deal with an accepted reality. And that hit me very hard. And as I say, it was kind of transformative to me, seeing that. And I count myself lucky that I only had that experience once.

It's never a good idea to get into the system, as it were. It's not good to spend too much time in jails, hospitals, mental hospitals, places that can permanently alter your way of thinking or living. I didn’t make a habit of it. But for me, this was kind of a fascinating experience, especially in retrospect. And it was some time ago.

That's sort of "rule number one," maybe, with memoir. It helps if you can process these things. It helps if you can delve into them with some objectivity and distance.

Sure, sure. How long were you in the hospital for?

It was six weeks. The summer of '78.

In places like that, you're in a completely different bubble and surrounded by people who have a lot of problems. Everyone there is there for a reason, and they're all seeing things through their own lenses which for the most part are also tinged by some sort of medication. It's an interesting and strange experience.

You're right also in that … all of this stuff, I think, is best served by time. Like, for instance, you certainly couldn't have written Chartwell Manor a second before you started working on that book. But you were at the right point in your life and career and your skills and everything else, for it to come together so perfectly.

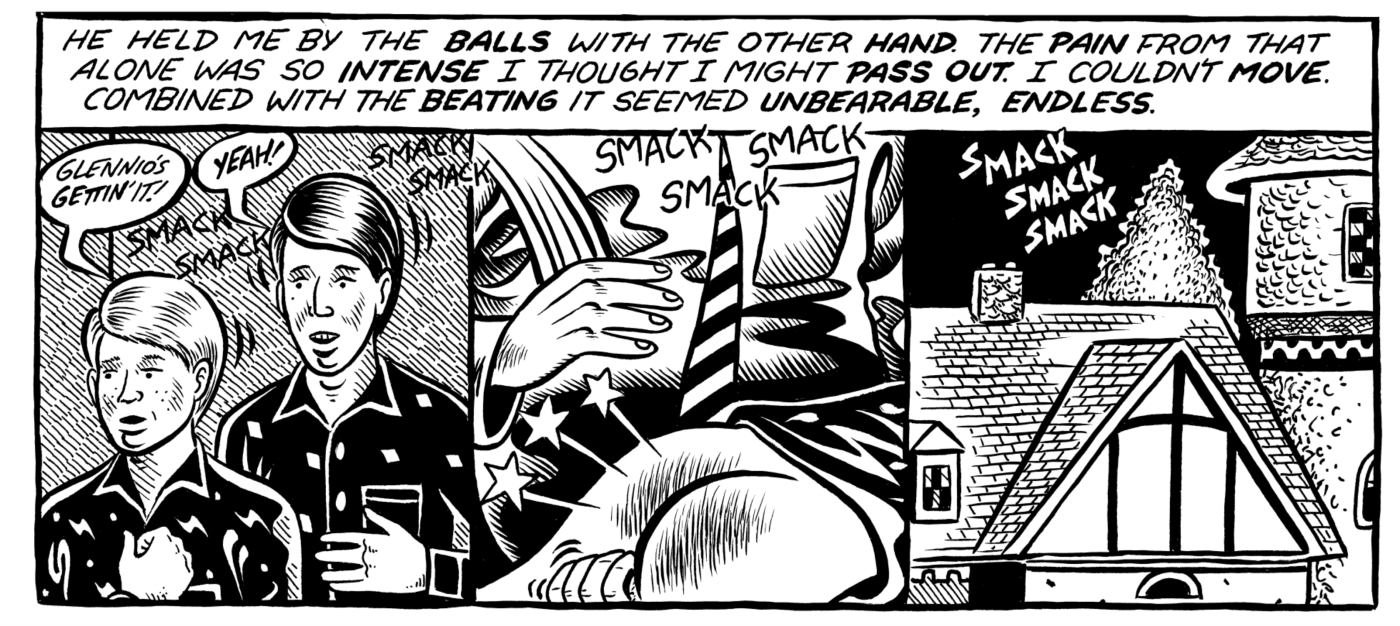

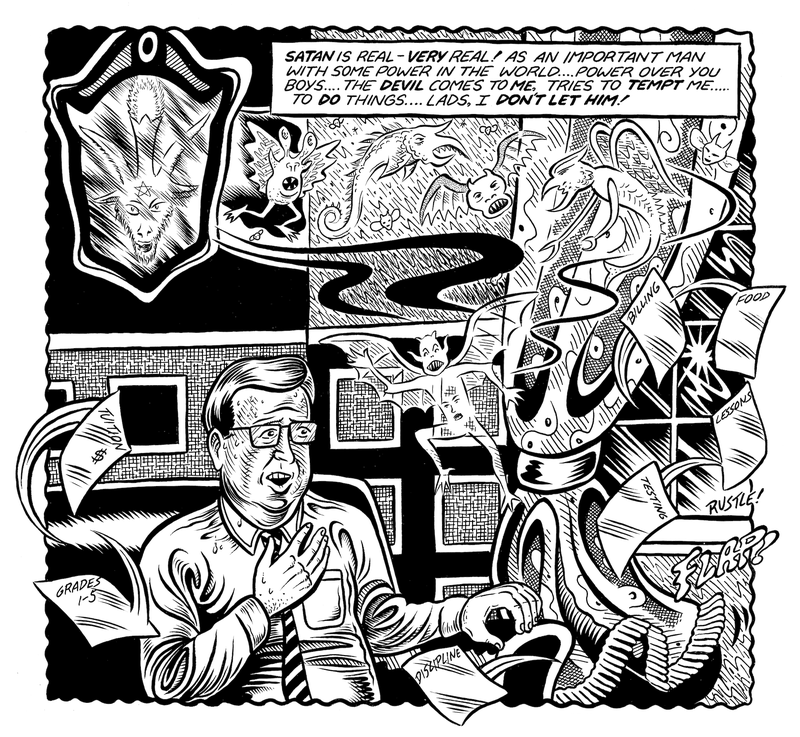

A page from Chartwell Manor. Courtesy of Glenn Head.

A page from Chartwell Manor. Courtesy of Glenn Head.Right. Yeah, I had actually tried it before as a 32-page comic and it wasn't working and I put it aside. It wasn't going to work in that short a format, which I didn't realize, but I knew I couldn't do it yet. In fact, with that one, I had probably started thinking about doing it from the time I was at the school because the school was so atmospheric and haunting and it felt like a horror comic. It had a spookiness that sort of hit me. But yeah, to be ready to deal with this stuff, you really have to be.

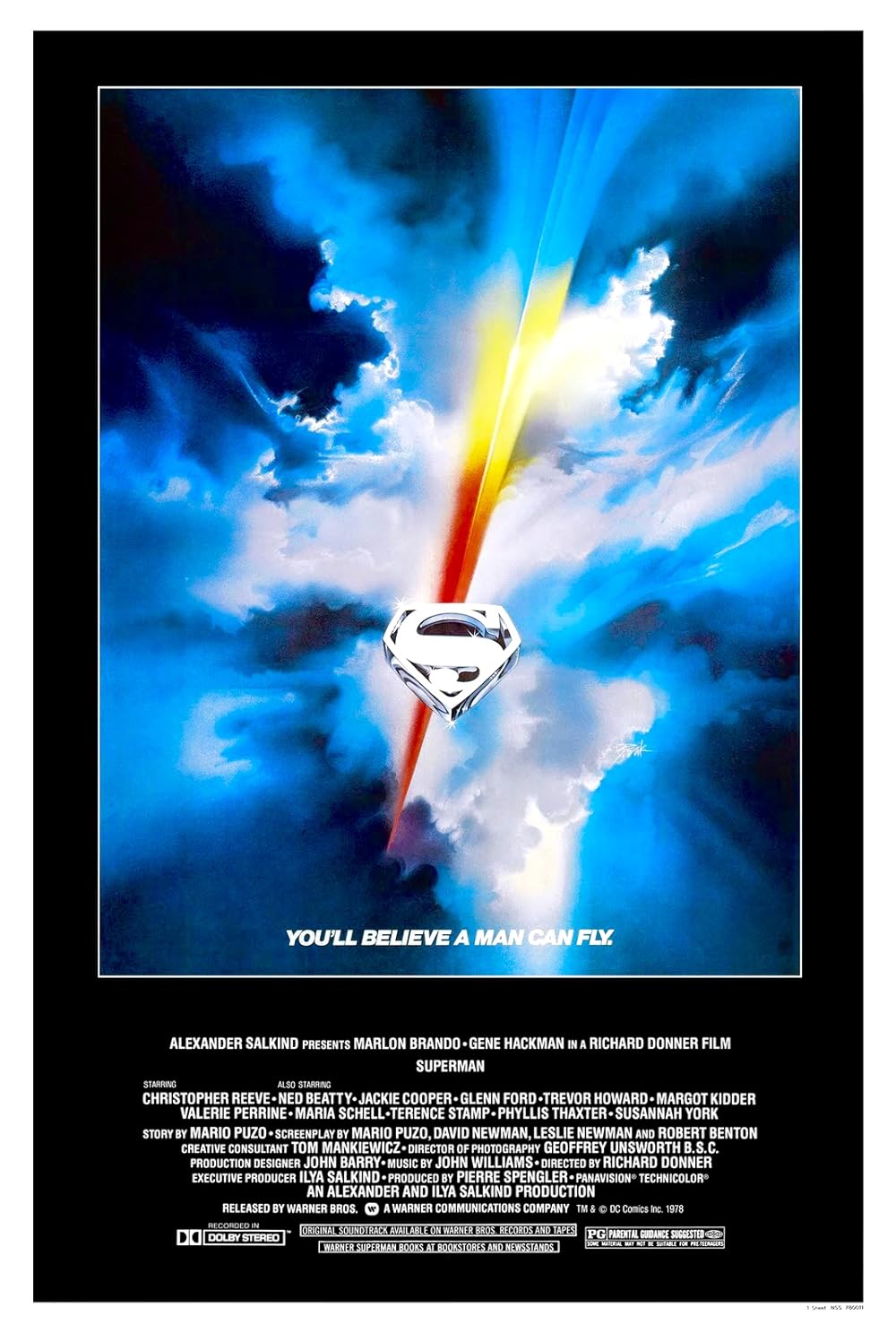

And I also really wanted to apply that experience to the experience of what underground comics do, which is really throw you for a loop. And into this world of demonic sexuality, which was also what was going on at the school. So it takes a while to see that those things might mesh, which is what I did when I wrote that book. It was important to me that those two worlds connect the world of underground comics and boarding school. There was even a comic back then that I read, which I'm sure you know, Crumb's "Joe Blow" comic [ZAP #4, 1969], which is this incest comic, and that I could easily sort of you know, conflate with the boarding school experience of all the sex abuse that was going on there.

So, but yeah, that's just by way of saying that all these things have to be sifted through for quite a while before you can make art out of them. I share some panels from that 32-page comic in Mark Newgarden’s class [at SVA], and it’s to point out that my characters looked a lot like Kim Dietch's in those pages, with those wide eyes, and I knew there was something not right about it, not even that it was derivative, but that this story needed to be grounded in a more realistic world if it was going to land. But if I'd continued on that path, I wouldn't have been able to do it. You're right. It was at that point my work moved into realism, I think.

Back in 1972, when he was 24 or 25 or something, Art Spiegelman did the first version of Maus in Funny Aminals, and it's just a couple of pages long, but it was the genesis of what would come later, right?

Exactly. It's the equivalent of a novelist who takes a short story and realizes there's much more here. This could be a novel. It was just like that.

Yeah, but he wouldn't have been prepared at that point to have gone into the painful depth required for what he later accomplished, right?

Oh, yeah.

Just like you wouldn't have been prepared to do the book that you're finishing now back in the Avenue D days.

There's no way. I look at it as filmmaking. It's one thing to make a short film. You can do it. You can get some of those scenes in there and it might be an okay short film. But to really make that into a movie, you've got to have all your chops down. You've really got to have the right screenplay. You've got to have everything together. You've got to know what you're saying. Plus, you’ve got to be willing to take the time that's needed to make that happen.

The other thing is, back in the day, with people doing underground comics or you know, the stuff that we were doing in the '90s, like Snake Eyes and stuff like that, you'd have to set aside all this time — not do any illustration work, not contribute to other people's comics — and just work on a graphic novel. That's done all the time now. But back then, you wouldn't do that. You couldn't do it.

There would have been a number of reasons why it would have been more difficult.

Right. I mean, you know, it helps that the graphic novel at a certain point became the only game in town. So that was the thing to do. Which leads to its own problems, because you see young people, talented people, fresh out of school, say, "I'm going to write a graphic memoir." And they're not ready to do it, and the work feels unprocessed. I got into doing it at the time when I was ready to do it. You know what I mean? You have to want to do it. You have to have a story you really want to tell. And it has to be the right time to tell it. And it has to be the kind of story that needs that treatment, you know?

What I really think about is the truthfulness of the work. And this isn't just about getting the facts right, but about looking at it through a self-critical lens, like where am I in all this? How am I complicit? I mean, what I don’t like in autobiography is trauma being invoked without being processed. It's a label in place of insight. The question always has to be, "Why does this still matter to me? What did this experience mean?" Without that, it's just a string of anecdotes, or a car crash on the highway. It's an artistic and even a moral imperative, I think, to ask these questions, to go beyond some pageantry of suffering to something deeper.

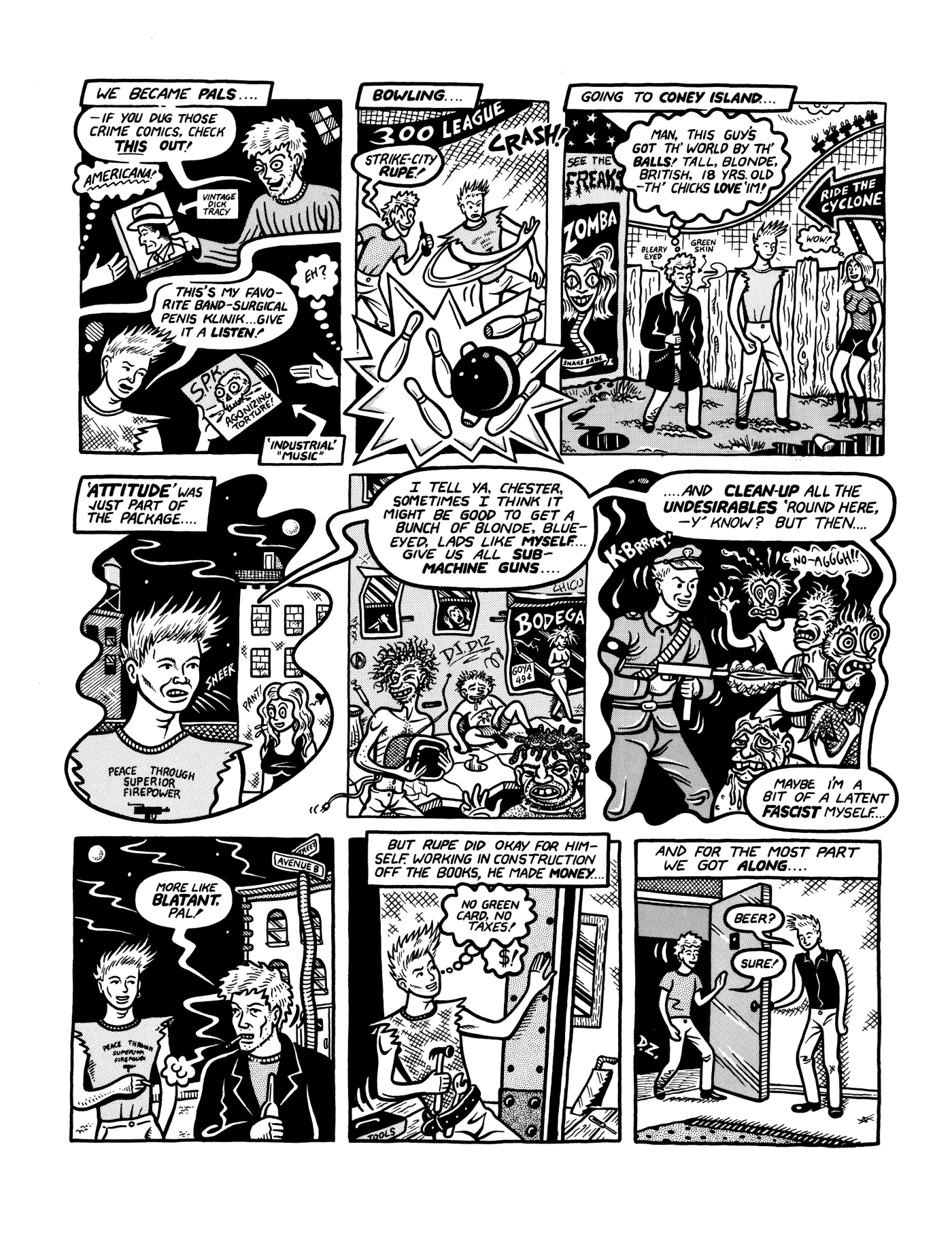

Bad times at boarding school, from Chartwell Manor. Courtesy Glenn Head.

Bad times at boarding school, from Chartwell Manor. Courtesy Glenn Head.Yeah. And you never know how your story is going to impact someone else. One thing I wondered, with your last graphic novel memoir, Chartwell Manor, did people reach out to you and say it struck a chord with them? The book deals with predatory sexual abuse and there are many people who, sadly, personally related to certain parts of it. But I also had people, some of them complete strangers, ask me about the book or about you, maybe because they knew we've known each other for a long time. I'm not sure. But many of them said how important the book was to them because it told their story. Not their exact story, but their story in a different way.

So, that's the other thing. I got a lot of what you're talking about. A lot of people contacted me saying I told their story. In some cases, literally. In other cases, not literally. And in some cases, people really related to it even though they didn't have anything like that happen to them. Which, you know, was really nice to hear. Yeah, there's a lot more people out there that have had things happen to them than they're willing to admit. And I also think that we live in a time — and maybe it's always this way — where things are getting a little bit more opened up than they once were. If I think back on the decades I grew up in, things were different. But by the '80s, for instance, there was much more of an awareness about child abuse that was coming out. And that continued to happen. And it wasn't stuff that people were necessarily going to be talking about. And yet, on the other hand, they kind of were and it became more of a thing, so people did want to hear about it and hear stories that they knew were true and how it affected those it happened to.

I didn't get into comics to get that kind of sympathetic human reaction from other people or have other people try and make me feel better about what I've been through or anything like that. But I also wouldn't turn my back on it either or say I don't want it. I mean, I'd say a lot of cartoonists are this way. We want to tell fun stories. We want to make cool art. We want people to like us. We want to get over in that way. You know what I mean? We want to deal with that level of being a cartoonist. Which I think is actually sort of an evolutionary kind of thing that you go through as a cartoonist because you have to be able to tell an entertaining story. You’ve got to be able to do that. I mean, you know, somebody like Justin Green isn't great just because he put all that [personal stuff] out there. He's great because he could put that into a format of comics, which no one else had done before that, but it was also entertaining. People wanted to read it, wanted to know his story, and they found it a kind of page turner. And that was the thing. One of the things that I was really happy with with Chartwell was that a great many people said they read that in one sitting. That's what I like in comics. The kind of thing that I was growing up with with comics. It was a lot like rock and roll. Or like, you know, you'd be driving, you turn on the radio and if there's a good song, you listen to it, then maybe you turn it off. Just fun, you know?

And comics have that kind of quality. The stuff that we used to see in Weirdo and other comics — maybe not RAW, but a lot of places — in a lot of cases comics were sort of selling themselves as disposable entertainment. Trash that was fun, and I love that aspect of it. But you're not just an entertainer if you're telling really personal stories. You know, Maus obviously isn't just an entertaining story. Art might hate this word, but it's really an important work. Maybe he wouldn't hate it, but it is an important work in comics and in literature. Holocaust literature even. I think the medium has really shifted gears.

Like they used to say, comics aren't just for kids anymore and that became a joke. And the more there became of the graphic novel, it seems like the more that has become accepted. That you know like a graphic novel can be just as good as a novel. Better. There's a lot of terrible novels out, so you know.

There's a lot of terrible ... everything. Anything that you can possibly think of, most of it's going to be bad.

That's the metric. Eighty percent of any given genre is going to not be good.

Yeah, but it's the twenty percent that are good, that go above, that draw you in. And that's what brings people back to them. And, obviously, this is all subjective too, right? Because my view of what's good is just that: my view. People can like whatever they like.

And they will. One way that I look at some of this is that, in a sense, art is always escapism. Comics is always escapism. It's a matter of what you feel comfortable with and what you find enjoyable. And how far you want it to go. Do you want it to go David Lynch weird? Because that’s another escape. For other people, it might be something much more personal and revealing. That's for me. So different tastes. You know what I mean? We're going to go after the stuff we're going to go after.

I think the good news is that the comics medium is still pretty well and alive and kicking. That people do want this stuff and I personally believe that we really have underground comics to thank for that. I've been reading Dan Nadel's Crumb biography and seeing how he would not sell out as an artist. That, I think, is in the DNA of alternative comics, or at least the best ones. That they, essentially, are not supposed to "sell out." They're supposed to be the best art they can be. It's kind of art for art's sake. Because if Crumb had sold out, if he had made a bunch of movies of his comics or if he had done whatever he had to do to have graphic novel bestsellers and shit like that, everyone else would have followed that. That would have been probably the next thing that everyone else did too. I think his influence impacted everyone that followed, you know what I mean? I think you can see it in all the other graphic novels that are very successful just on their own terms. And that's the point that these things were supposed to be good on their own terms–first and foremost. That's one reason why he's still such an inspiration to so many people, you know?

From Asylum. Courtesy of Glenn Head.

From Asylum. Courtesy of Glenn Head.In what ways has Asylum changed from when you first started working on it?

Well, it looks better now that I've inked it.

But the general guts of it and everything? I had seen your early pages. Is it pretty much the same?

I think it is. But what you saw is different from what the book was looking like for a while. I’d already penciled a lot of the early pages when I showed it to my wife. She’d helped me figure out how to take those things that were preoccupying me from that time my life — friendship, insanity, art, death — and sort of yoke them together in a narrative that could help me make sense of what I had gone through. But when I showed her the early pages, she was like, "This is not working."

We were away in Philadelphia, and we were talking about the book in this restaurant, and I was miserable. And the food was miserable. And I was kind of glad in the end because I never wanted to go to that restaurant again. She thought I could actually use a lot of the material I'd already penciled but that it would have to be rearranged. And it took me a long time to figure out how to do that. And it wasn't, at least according to my wife, it wasn't a very pleasant place, our house at that time.

Basically, I had introduced Rupert within the first few pages, but my wife was saying that we had to get to know me better, get to know my environment better, to appreciate how vulnerable I felt at the time. I was living in the East Village, which was a genuinely dangerous place in the '80s, and I was struggling in art school, and if the reader doesn't know that, then they can't appreciate what someone like Rupert, someone with that kind of brashness and confidence, would mean to me. It's the old stranger comes to town trope. And I think that's where experience with genre can come in. Those conventions have become conventions for a reason. They work. And they're also a way to ground the reader so that they’re invested enough to go on a wilder ride with you. This is why the mental hospital chapter is toward the latter part of the book. I sort of needed, I think, to gain the reader's trust. So that they would know the world they were in was a safe place to walk around in. I think people are frightened by mental hospitals, understandably. And if you start a story with, "I got this mental hospital story, you're going to love it," they're going to maybe be a little bit like, you know ... So that took a lot of work and writing the characters of myself and Rupert was something I spent a lot of time with, because I had to make myself vulnerable. I had to make Rupert the leader, the guy who was in charge, which is pretty much accurate. But I even turned the volume up on it and made myself a little more vulnerable than I would have been just for the sake of the story. A lot of time went into putting that together and making that really believable, making that friendship really believable.

The thing you want with a story with characters is when people read it, they think: "It could not be otherwise." Of course those characters would get along that way. Do you know what I mean? Like that needs to be set up. I guess I'm just saying that a lot of work went into getting this narrative exactly as I wanted it.

It's key with any comic, but it's really key with a graphic novel, I always think in terms of screenplay and that's what I was doing here. I just, you know, for me, it's just about taking as much time as is required to get it to be exactly as good as I think it can be. My whole process of working, especially with a graphic novel, is really all about the writing. I think of myself as a writer who draws and I spent a lot of time writing this and conceiving the structure of it and what was going to work best.

Glenn working on a page from Asylum. Photo courtesy of Glenn Head.

Glenn working on a page from Asylum. Photo courtesy of Glenn Head.Yeah. So what about the experience of having done two previous autobiographical graphic novels? What are a couple of the things that you learned from doing those first two that is informing how your process with this one?

Well, you know, I learned that what you learned writing one book might not apply to the next book! But I think the main thing is that I have become much less fearful about going as far as I need to in telling the story. Showing whatever parts of myself I feel like showing. I'm not afraid to do it. And that's what you get from doing this kind of work. There's a part of you that can be kind of fearful about self-exposure, but when you get a good reaction, instead of a bad one, it makes you think, well, I can continue doing this.

From Chicago. Courtesy of Glenn Head.

From Chicago. Courtesy of Glenn Head.My first book, Chicago, I'm in these extreme states, starving, on the streets, meeting my comix heroes and coming away disillusioned. And I end up in the attic of the family home, naked, with a handgun at my temple! You think, "Man, what're people gonna do with this?"

That was how Chicago, my first book, could lead up to Chartwell Manor, because people reacted favorably to that. And so I knew I could do something that really put things out there — like sex abuse and alcohol and sex addiction and things like that — into the mix and use them as material. And the more I've used this kind of material, the better I feel about using it. And the better I feel about it, the more time I can spend drawing it, which is good because graphic novels take a long time to draw.

So that's been my experience. I think it was de Kooning who said, "how far can I take this?" And that was in relation to the fact that he had done a lot of painting. He had even done what he knew were good paintings. And then the question became, how far can I take this? How much of myself can I put into this? How far can I push this? And obviously, I couldn't do the book I'm doing now as my first graphic novel. It would be too out there. And I don't know that people would have been willing to go with it, but it's a question of building towards things, you know? That's how I see it.

TAMMI MORTON-KELLY: In the introduction to Chartwell Manor, you write that you use the word trauma just once throughout the entire book. But in page after page after page, trauma resonates. As a reader, when I look at the expression on the Glenn Head character, I can immediately identify what he's feeling in each scene. It does speak to trauma, but you're not overtly saying it. It's the aftermath, and it comes out very clearly on the page. I can tell, "Oh, that's the perspective I'm taking."

I'm glad that's how it's coming across. That's what I'm trying to do. It's not enough to present trauma: "I was incested." "I was abused." The great memoirist Vivian Gornick talks about the situation and the story. The situation is the trauma. The story is how did I grow up with it, grow through it. What meaning did I make of it?

From Chartwell Manor. Courtesy of Glenn Head.

From Chartwell Manor. Courtesy of Glenn Head.You could not have written Chartwell when you were 25. You could have written something, right? It wouldn't be what it ended up being. So there's years of perspective, distance, and healing.

The other word is processing.

There's no vivid image of the ultimate trauma — the sexual abuse — in Chartwell. You didn't feel the need to present that and that makes it even more powerful, in my opinion. Not presenting it evokes empathy.

What's really important to me is that the reader experience what I experienced. That's what I'm really trying to make happen, so when they read it they get what I got, or they get something like it in a way that they can handle. I would never have been able to do anything like this book in a much earlier point, you know, like these other artists we were talking about earlier. Like Phoebe Gloeckner and Justin Green. It's amazing to me that they were doing that kind of work when they were in their twenties or early thirties. I think — this is just a theory — but I think that took everything out of them, because Phoebe hasn't done any comics since then. I think that the impact of facing that work on the page is just a lot [to deal with]. But in another way, for me it was truly liberating and cathartic. Chartwell was the most enjoyable comic book I've ever drawn in my life. Like, there's this one scene towards the beginning where my headmaster is telling a bedtime story about Satan worship and it's just off the charts. Man, it's just so fucked up and I'd been waiting my whole life to draw it. Because it was just weirdly Gothic and terrifying for little kids to hear! Even as a kid, it really appealed to this part of me that liked monsters and haunted houses. Drawing those kinds of scenes was really enjoyable but I would not have been able to do it at a younger age. I just don't think I could get my hands around it and make it work.

I would tell anybody that's going into memoirs, either in comics or prose, that one of the first things to do is try to find a way into empathy for everyone. Not just you, not just the antagonist or whoever it was who fucked you up, but the more empathy you can find ... it's just like an actor who's trying to play a character. If all you can find is the villain in that person, it's going to be a shit performance, so you really have to find ways into vulnerability for every person. Because if you do that, people are going to feel for those characters. That's really what you want. Like, I didn't really want anybody hating Lynch. The real drama in the book is between me and my parents. It's really, it's a family story, and that's where the drama is. Lynch was like a rattlesnake in the room. It's just a rattlesnake. This guy was a pedophile and that's just what a pedophile does.

A rattlesnake does what a rattlesnake does.

That's exactly right. I've known some evil people who weren't good to me in my life and I don't take it personally because if it wasn't me, it would have been somebody else. That's just what they do. So I can look at things that way, at least a lot of the time, and I can get that kind of philosophical distance from it and just see that the world has such things and such people. I think it's necessary to try to get there if you're going to work with this kind of material. You shouldn't be trying to get anybody on your side, you know what I mean? You're not actually trying to make friends. Comics are, at a Bedrock level, entertainment, and if you're not meeting that level, you're really screwed because nobody's going to read what you're doing. But you need to meet that hurdle and get over it so that you can get to what anybody is really looking for in a memoir, which is insight. That's basically what they're paying for. Can you show me, truthfully and faithfully, what happened in your life and show insight into those experiences? And will that that insight resonate for me? Will I be able to fathom what you mean and what you experienced?

English (US) ·

English (US) ·