John Kelly | January 20, 2026

Photo booth shots of Glenn while he was a SVA student, ca. 1982.

Photo booth shots of Glenn while he was a SVA student, ca. 1982.In the second part of this career-spanning interview with Glenn Head, we focus on his childhood in suburban New Jersey, his time in and out of art schools, and the vast body of experimental work he created prior to returning to the autobiographical form. Included in this section is a look back at the time when I first met Glenn, when he was living in a seedy part of Brooklyn and editing (along with Kaz) the great alt comics anthology Snake Eyes. The late '80s/early '90s were a special time for those of us living in New York who were part of the fringe comics community. The New York comics scene has changed since those days, as has the city itself. And so has Glenn. As Mark Newgarden wrote in a 2021 Comics Journal interview with Glenn, "Glenn Head was the ink-brush Charles Bukowski of our little NYC comics scene back in the day." The Glenn of today has emerged as an artist in full command of his craft, and one who is making what are among the most compelling autobiographical comics...ever. As Robert Crumb said about Glenn's last book, Chartwell Manor, (which he also called a "masterpiece"), "Head has traveled a long way to get to this point." I greatly look forward to reading his next installment, Asylum (Fantagraphics, forthcoming), which we discuss in part 1 of this interview. I hope there will be many more. — John Kelly

JOHN KELLY: For someone who has written two autobiographical graphic memoirs that focus on your early years, this might be a curious line of questioning, but ... let's go a bit deeper here. Beyond what you've depicted in your books, what was your childhood like? What were your influences? What were you reading? What were you watching on television? What was shaping you at that time, growing up in the 1960s in the suburbs of New Jersey?

GLENN HEAD: Yeah, being a baby boomer kid, I grew up with all the obvious stuff. I was born in 1958, so, you know, the kind of shows like Gilligan's Island, Get Smart, all that kind of stuff that was a part of pop culture as I was growing up. But it's an interesting question because I've thought about this a lot. I have this theory that for any cartoonist, the DNA of what first hits you stays with you and has an impact on everything that you do after that. And I realized that what that was, in my case, was Peanuts, which was actually the first comic I ever read, and I read it intensely.

I didn't read it in the papers, because I didn't read newspapers. I was a little kid, but it was already collected in paperback, right? So, reading Peanuts was completely eye-opening and just kind of an explosive read for me as a kid because of the fact that it really captured childhood trauma in this way that I had experienced myself. So I felt this intense identification with Charlie Brown. And being in third grade and having a lot of those feelings about failure and all that, it just was really profound to read as a comic. It was also very funny. And being the master storyteller and joke-smith that Schulz was, you know, you could identify with other characters if you felt like it.

A Charles Schulz Peanuts panel.

A Charles Schulz Peanuts panel.But the point about Peanuts was that it was something with a great deal of childhood interiority, you know, in a way that I haven't seen better since, in terms of how it captured how painful kids’ lives are. The whole thing of what was going on, and Charlie Brown's life, and the failure and the sorrow — it was the first comic I read, and I read it pretty fanatically, and I think that had a huge impact on me. I think it probably really drew me to autobiography before I even realized it because it has anguish baked right in.

Before that, I really liked Dr. Seuss, which is another example, and you can maybe see some of that too in my work, because the fact is that there is a kind of surrealist weirdness and craziness going on in a lot of my stuff stylistically. It may even refer back to that unconsciously because that stuff was really a lot of fun, and like any kid, you’re looking for fun. I just think that this is why I mentioned that nothing else like Peanuts really existed as a way of reflecting what life was like for kids, so that was really the first comic I read that really, really hit me.

Well, it captured just how awkward and painful childhood could be for some. I think it was, at least superficially, somewhat autobiographical for Schultz.

It may have been. I don't know, and I didn't read the biography of Schultz.

I don't mean overtly autobiographical, right? It was just — he seemed like a fairly depressed person.

I think the main thing I'm referring to actually is the loneliness that that strip captured. I don't think loneliness had really been a theme or a topic that was dealt with in comics, especially for children. I think that's probably it, the sadness of it was kind of profound. I mean you don't see anything like that in Nancy. The emotional stakes in Peanuts are very high. You read that strip and you laugh, but you also feel something always, in my opinion. And they're all pretty sad characters, you know? Like Lucy is in love with Schroeder who doesn't really want anything to do with her, and Linus is getting beat up by his sister and he can't give up his blanket, and Pigpen is unwashed. For a comic about kids, it really had its rough edges, you know, and that captured something of what I knew growing up, and that's what we always respond to. Does this speak to me? Is this something I can identify with? And with that strip I really could, so it it hit me in a way that most other pop culture stuff didn't.

Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman's "Starchie," from MAD #12, 1954.

Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman's "Starchie," from MAD #12, 1954.Back then, when I read MAD magazine, it wasn't so much that any of that really spoke to me either, but it was also just kind of a ... it was a comic, and comics were "bad" for you, and you weren't supposed to be bringing it to school and it could get confiscated, right? But when I was in seventh grade, there was a lot of bad stuff going on in schools, a lot of aggressive bullying behavior. It was around this time that I got the MAD comics that were put out as paperbacks. There was a strip called "Starchie," and that strip was amazing because it really reflected a lot of the school stuff I saw around me at that time. This kind of juvenile delinquency behavior that was really off the charts violent. It was also kind of a proto-underground comic, so seeing that was also really an eye opener. A lot of what Harvey Kurtzman was doing in MAD was kind of grimy and dangerous seeming, a lot of it. That's sort of how it impacted me, all the crazy details and the energy of what Will Elder and Wally Wood were doing. And there was "Superduperman." That really affected a lot of kids. Everybody was doing their own version of "Superduperman," and that was just a really funny splash panel because it showed this muscle bound heroic guy beating up some cripple which was just so sick that that every kid liked it. I was attracted to this underside of things that were not shown much, but when it was in this context ... it was kind of off the charts and kind of not generally accepted.

What was going on in your life and your world that was making you identify with that loneliness?

I think it’s probably the universal thing in childhood, when you learn that the world is a cruel place, doesn’t necessarily care if you live or die. I think of that as essential to childhood. Somehow Peanuts communicates that. I was a pretty lonely kid in grade school, and I didn't like it much. And it was partly that. I mean, as I was just saying about “Starchie,” the violence in there was really grimy. It captured the world I was living in. With kids beating you up, attacking you in the hallways. Junior high school was just a hellscape for me. And this is before I went to boarding school!

I never read superhero comics or had any interest in any of it, and seeing that kind of behavior, which is really abhorrent, was something that I saw a lot of. I think I was just really attracted to that in a perverse way, that darkness. I guess I grew up around enough of it, that when I saw reflected back in comics, I was drawn to it.

And all this burgeoning craziness dovetailed with my interest in rock 'n' roll, which was coming on big. And a lot of the behavior there was risky, not good for you, and very attractive to me. A lot like the underground comics I would soon see. None of this stuff was good for you or meant to be.

What contributed to that loneliness, though, to put it into context?

I didn't do well in school, and this is in New Jersey. I had friends but we fought all the time. And that was allowed — a kind of "boys will be boys" thing. There was a lot of freedom, just be back for dinner by 6. But other than that, anything could happen, so it was kind of wide open. And boys' behavior back then was that you settled things with your fists a lot of the time. That's just what I grew up with. That's what there was when we were in grade school, and it wasn't questioned. It was just part of how things went. And, on the other hand, you were supposed to respect authority. And because I was a kid with ADD, I would zone out in grade school and just think about stuff that I wanted to think about, whether it was some TV show, like Man from Uncle, or some comic or the Batman show or something. I think I was developing a taste for escapism, and comics are the one of the best forms of escapism, because they're easy to read and they're selling you on excitement.

Were you reading any other comic books?

No, none of the "classics" like Dick Tracy or Nancy. That happened in art school. Comics weren't really allowed much in the house growing up.

What was the issue with not allowing comics in the house?

They were disreputable.

As a teenager, I had this book called A History of Underground Comics by Mark James Estren that just blew me away, just a wild compilation of all these different artists: Wilson, Crumb, Osborne, Rory Hayes, the whole gang, with chapters like "Sex" and "Violence" and "Drugs." It was like a crazy visual orgasm seeing it. I was hooked. My parents were livid, but I managed to keep it. We fought about it.

Years later, I had a friend who told me that his mom had actually bought him that book when he was a kid! He was drawing comics, too, but he bailed on it. And I wondered whether the mom had killed his rebellion just by encouraging it!

Can you give an overview of what your image of your dad was at that time, when you were younger, and then describe him as you matured?

Well, my dad was very straight, this businessman, a Wall Street guy. I don't think he saw the craziness of the era, the '60s or '70s, or didn't want to look, maybe.

But my dad was really very loving, taught me how to read, because I just wasn't learning in first grade. He had this phonics book, and he sat me down with it, and when we finished it, I could read.

It's important to remember things like this, because human relationships are always a mixed bag, and of course things got much worse between us later. Neither of my parents really had the bandwidth to deal with or even admit what happened to me in boarding school. He spoke in platitudes. I got angry. From there it went south.

We're all products of our environment, obviously, and the one that he grew up with was a lot different than mine. So as I was getting older, if I might need answers to questions or anything, I don't think he was capable of delivering, and he might offer a platitude or something like that, and I might respond with sarcasm or hostility and we were drifting apart really quickly as time went on. And as a result of that, school wasn't going well, and I got sent to this boarding school, Chartwell Manor, when I was 13. And the thing about something like that is that whatever bad happens, you can't take it home with you and discuss it or get it straightened out because you are now someone else's problem. But so those are all things that factor in. I mean, I think personally I am somebody who has a built in distrust of authority. If anybody's telling me anything about how something is, my first response is to ask why, and if I don't like the answer I'm going to keep asking questions. From there, trouble may ensue if I don't like what I hear. So I think that's how I connect a lot of this. But also, as I was saying, life gets more complicated for you as you are no longer a little kid and that can make things difficult for you as a parent if you don't really feel like answering to it. I have four sisters, and it's much easier if everybody is just conforming and I wasn't really about to do that as might have been expected.

Was that distrust for authority innate? Did it stem out of something?

I think it probably related to the fact that my older sister was a bit of a drill sergeant to me and my three younger sisters growing up. So I became a bit rebellious. This was also an anti-authoritarian era, so from my side, it seemed cool to get into trouble, and I had an attitude.

This older sister, though, I was close with. We bonded over the music we were listening to: rock ‘n’ roll that was troublemaking. I think I was looking for a way out. Comics was also all about that. There was a bomb-throwing sensibility to the stuff I loved, a kind of assaultive nature to it. Going on the attack. I connect all of this to those early MADs.

My parents were transplanted midwesterners. They grew up in Iowa and Illinois, respectively, and when they came out East and my dad was working on Wall Street, he had these farms in Illinois that he was having farmed. So I'm from a wealthy upper middle class family. I guess the idea was it felt repressive. Without necessarily saying, "don't read this, don't read that, or don't be involved in certain things," there was the idea that you probably shouldn't be doing the things you were attracted to. One of the ways that I would contrast the era I grew up in with — not just my parents era, but especially the current one — is that when I was a teenager, I went to a local Madison Library and asked about this book I had heard about by William Burroughs called Naked Lunch. No one I knew had ever heard of it. This was in 1976 or so, and the library had it on closed access, so I was allowed to see it but I wasn't allowed to take it out of the library. I walked out with it, stole it, and I kept it. This really disjointed, fractured, anti-narrative — it broke every rule. And culturally, there were a lot of different corners that were there that you could delve into that not everyone knew about. You could really dive into them and they were there if you sought them out, but they weren't just going to jump out and alert you to them. So you have to find these things out and that was how I grew up and that's how I looked for things and found things.

I think about that and the culture I grew up in versus the one my sons — who are now all in their 20s — grew up in. When you and I were growing up, we had to work at finding things in a way that is different today. There was a lot more exploration, and human interaction, required if you wanted to find out about things. It was more of a treasure hunt where you had to actually go into places and talk to actual people — libraries, record and book stores — and not just type things into your phone. I'm not saying that one is better than the other, but ...

I was the only kid I knew who knew about underground comics. I was looking at them when I was 12 or 13 and this is around 1972, so nobody I knew really knew anything about them. So I kind of felt like I was the only person on Earth that read that stuff. I mean, I didn't so much think of it as cool, I just knew it was the stuff that I liked. In some ways, it made me feel like a bit of a weirdo, you know, like I'm the only person that knows this stuff. So, I think I was probably accepting not fitting in, because I was just going to take the stuff that really worked for me that's just how it was going. I figured they all thought I was some fucking weirdo, like I was on another planet, liking this stuff.

But, I guess, there's good weirdo and bad weirdo. There's the weirdo where you feel like nobody likes you because they all picked on me, and then there's a sort of a weirdo who can wear it as a badge of honor or something.

Which is what I eventually did. I mean, I started cultivating more of a rock-and-roll look, not wanting to be like any of these jocks or preppies or squares that I didn't like. Ultimately I have enough of a rebellious streak that I'm not really going to fit in, but on the other hand, as a teenager you really do want to fit in ... being a teenager can be kind of tough if you're not part of the status quo, not part of the crowd ...

How did you dress differently than your peers?

I looked for whatever cooler clothes I could find and I'd wear sunglasses in class and shit like that ... just the kind of stuff you're not really supposed to do. Anything that I could do to stand out enough that it might look cool and maybe be attractive to some of the cooler chicks in the class, of which there were not many. Just looking for some way to stand out and be a little bit different.

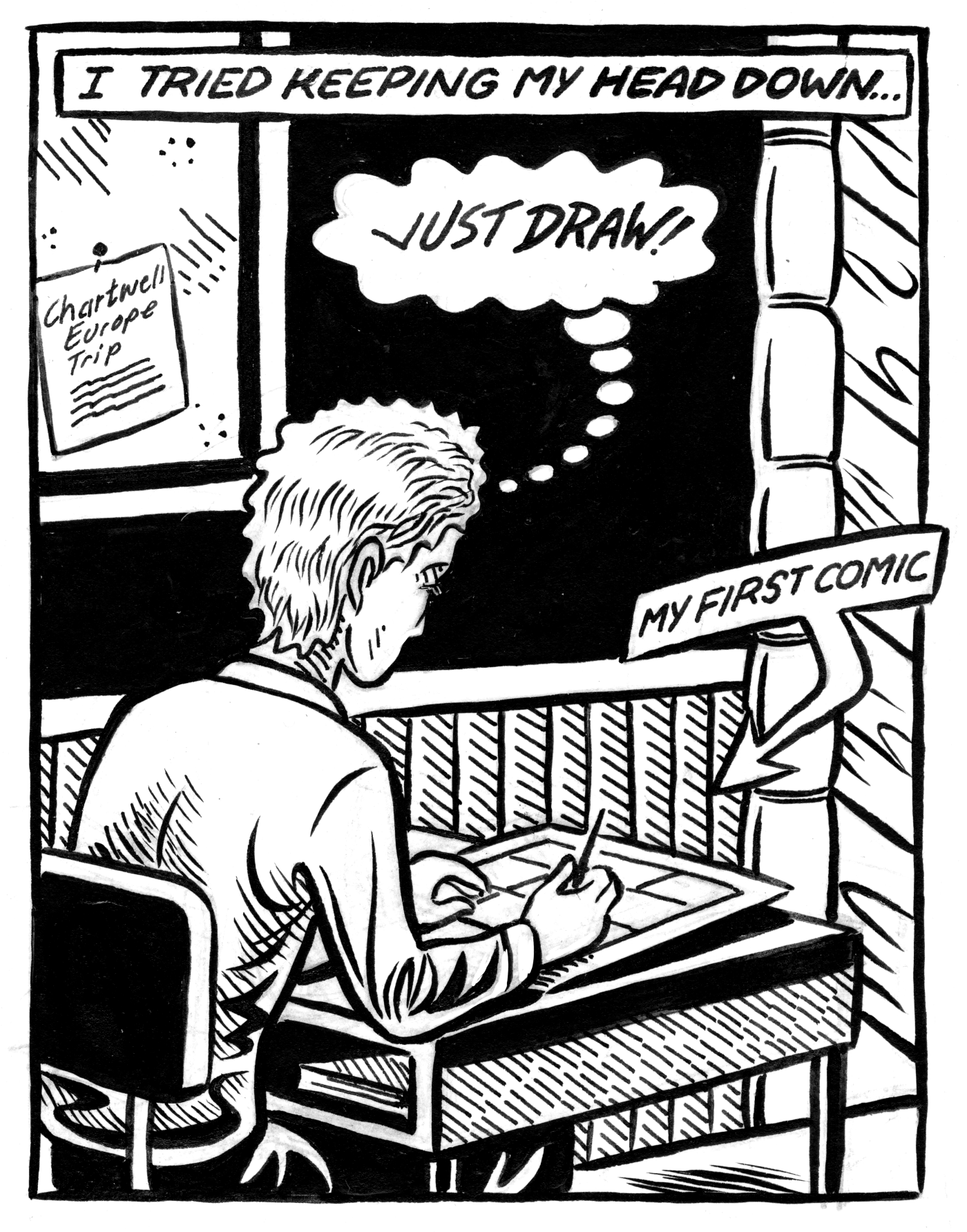

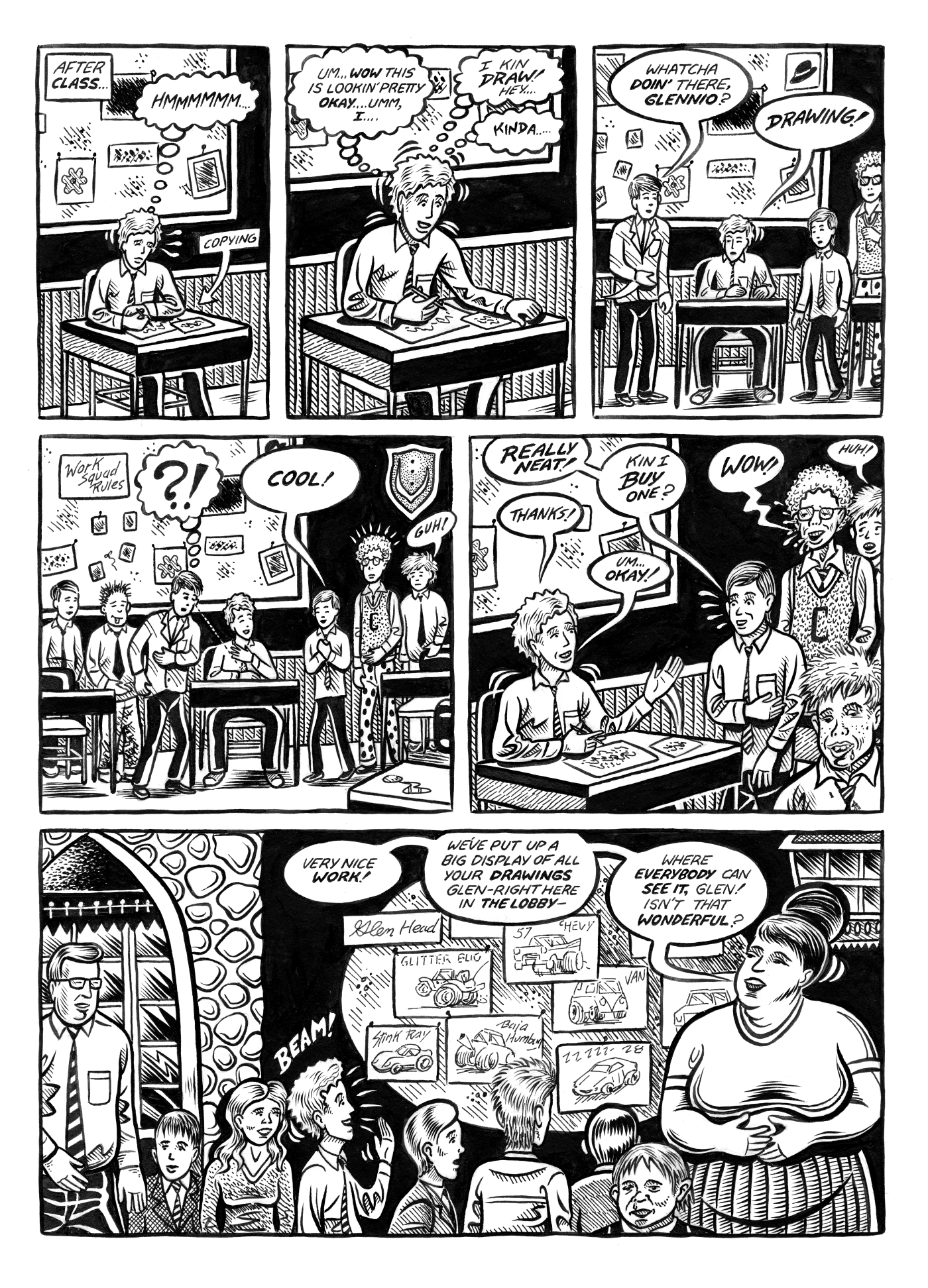

Glenn draws his first comic, from Chartwell Manor. Courtesy of Glenn Head.

Glenn draws his first comic, from Chartwell Manor. Courtesy of Glenn Head.And by this point, had you been drawing a lot?

Yeah, yeah.

So, you were drawing from a very early age?

Yeah. And this is in my book, Chartwell Manor, but what happened was that at that time I cultivated and fostered an identity as an artist just by, you know, drawing fast cars and things like that and I found that I could do it and the other kids liked it. So, the one thing that was the upside of being sent to Chartwell Manor was that became my new identity and I sort of forged that there. I was carrying my art around with me everywhere I went, showing it to people and, you know, cultivating that identity.

Was there anyone else among your peers who was also drawing a lot?

A couple of kids I knew, including a guy that I still run into on occasionally. Yeah, there were a few kids. It a funny thing and I think about it sometimes is that the artist ego is such that you want to be the best artist in your school. You want to be the best artist in your crowd. The ego stuff asserts itself really quickly. As soon as you're making art you want to be the best. You want to be better than those other schmucks, no matter what stage of development you're at. And at Chartwell Manor I was! Of course, that’s like being the tallest man in a midget contest. Still, it was something.

Glenn the "class artist." From Chartwell Manor. Courtesy of Glenn Head.

Glenn the "class artist." From Chartwell Manor. Courtesy of Glenn Head.Well, I think, to a certain degree, being competitive can be a very helpful thing.

Yeah it can be helpful. I'm just saying one way or another, it's very potent. As soon as you start making the art you struggle with it then it starts getting good and you're like "wow, this is great I'm the best ever," like that, it really comes with it.

Even during the RAW and Weirdo eras, I think some of those artists would see what others were doing and, even if they have a completely different style, they were like, "oh, look what he did ... next time I'm going to go even harder," or something like that. I think that's like a healthy competitive …

Absolutely, yeah that definitely happens, for better or worse. S. Clay Wilson had this enormous impact by pushing the envelope about what was acceptable to draw or not and then after that everybody pushed it even further, so those things are always happening. That's how art circles develop.

Supposedly, or at least the way I heard it, a lot of people have that reaction ... for some of the other underground artists, when Crumb arrived and he was doing everything that they were thinking about doing, or were just considering doing, it really blew them away that he had gotten there first. They had all grown up on Kurtzman and E.C. and then Crumb arrives and not only can he do what they're only imagining doing, he's doing it a million times better than they realize they'll ever be able to do it. On a completely different level. It's funny how it works, because, you know, I could look at people's work like Kaz or Pascal Doury and I'd be blown away and think, "wow, this is on another level that I can't do," but on the other hand, it would really inspire me to try. So it would be very exciting. There's a part of it that might be intimidating when you see people that are that great, but on the other hand, it inspires you to want to be as great as you can be and to make your work better.

When you were later in art school, what was it like to be around other artists your own age?.

I had a really checkered art school career, starting with the Cleveland Institute, where I got thrown out for being crazy. And then I ended up on the streets and wound up in Chicago and that's what my graphic novel Chicago is about. I met Skip Williamson, Crumb, and all these people and had these very intense experiences about what the whole underground comics thing was. That hit me on a really deep level, like what's it like to be on the street? How low down does life get if you follow this pursuit?

What was the Cleveland Institute like?

It was a very straight place. It was like a five-year thing, and I just went there because I didn't really know what other art school to go to and they took me and it was thought to be good and I went there. It seemed to me really repressive, but I just wasn't in any kind of headspace. I was 19 and in no way was I capable of being disciplined enough to show up for class and do all those things that you're supposed to do to really get that kind of education. I was incapable of realizing that I had a lot of things I had to learn, I just wanted to get out and do shit, which I did by going to Chicago. Of course I created a lot of upheaval for my parents. They didn't know where I was. They had no idea what I had gotten up to. So these were really explosive experiences that took place instead of going to art school.

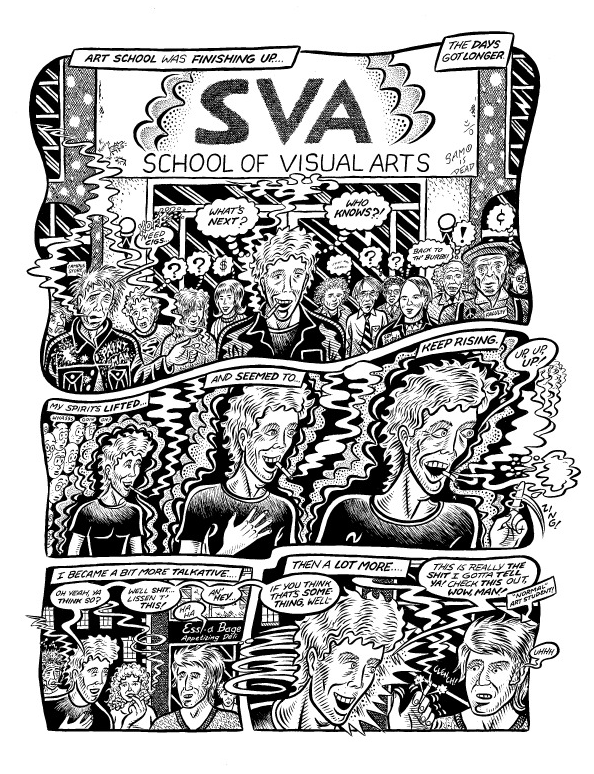

SVA days, from Asylum. Courtesy Glenn Head.

SVA days, from Asylum. Courtesy Glenn Head.I went back to school the following year to the School for Visual Arts, and I managed the neat trick of actually getting thrown out of SVA for being pretty crazy. And finally, at age 23, I went back to SVA. I think it was the fall of 1982, possibly '81 — I took Art Spiegelman's class, and I think of it as being very telling and very important that I did all that crazy shit earlier and I won't say I got it out of my system, but what I did get out of my system was the idea that I was not going to have to struggle to learn anything. Because when I took his class, I found out in short order that all I had done was cultivate bad drawing habits and I was going to have to start from scratch. And he was pretty rough about it, as was his way as a teacher. So it wasn't the kind of thing like, "Your work is really good here and here, but you need to do some work here." It was more like, "Your work isn't any good at all" and that's how Art put it across to me. So, because I was 23, and not willing to throw it all under the bus again, I would come back and take more abuse each week and get better. That's what I dealt with a lot at that time, for three years. My friend Jayr Pulga, who was in my class then, he was the man to watch. He was a real prodigy and a major talent and became my best friend. He didn't produce as much work as everyone would have hoped for. He's my best friend and a great artist and so that was the context. Early ‘80s. Kind of a blistering experience. But a formative one.

I won't probe you on it, but Jayr's one who I really wish did more comics.

You and everyone else. And, actually, he is working on a collection that Mark Newgarden and I and Jayr are putting together. There's a lot of great work in there, both the old stuff and the new.

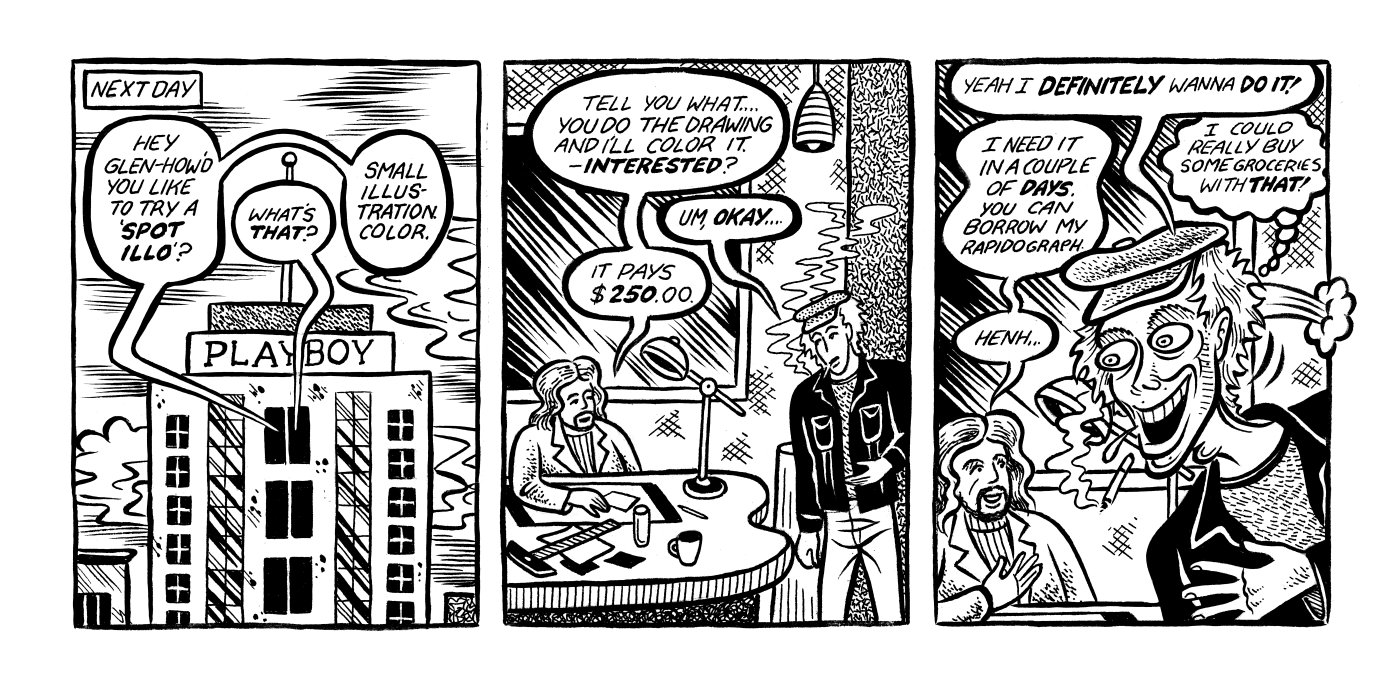

Top image: Nineteen-year-old Glenn gets an assignment for Playboy from Skip Williamson, from Chicago. Above. The illustration that ran in Playboy. Images courtesy Glenn Head.

Top image: Nineteen-year-old Glenn gets an assignment for Playboy from Skip Williamson, from Chicago. Above. The illustration that ran in Playboy. Images courtesy Glenn Head.Well, it can be good to have some version of a gun against your head. You can be very productive if someone's got a threat over you.

(laughs) Yeah, I think that's true. I think that's been my experience, that gun gets pulled out, and I'm like, "Draw!"

I guess that might be the best case scenario: You get published in Playboy as a teenager and then you think you're hot shit, or you've done it all already, and then reality actually slaps you in the face. And now the real work begins ...

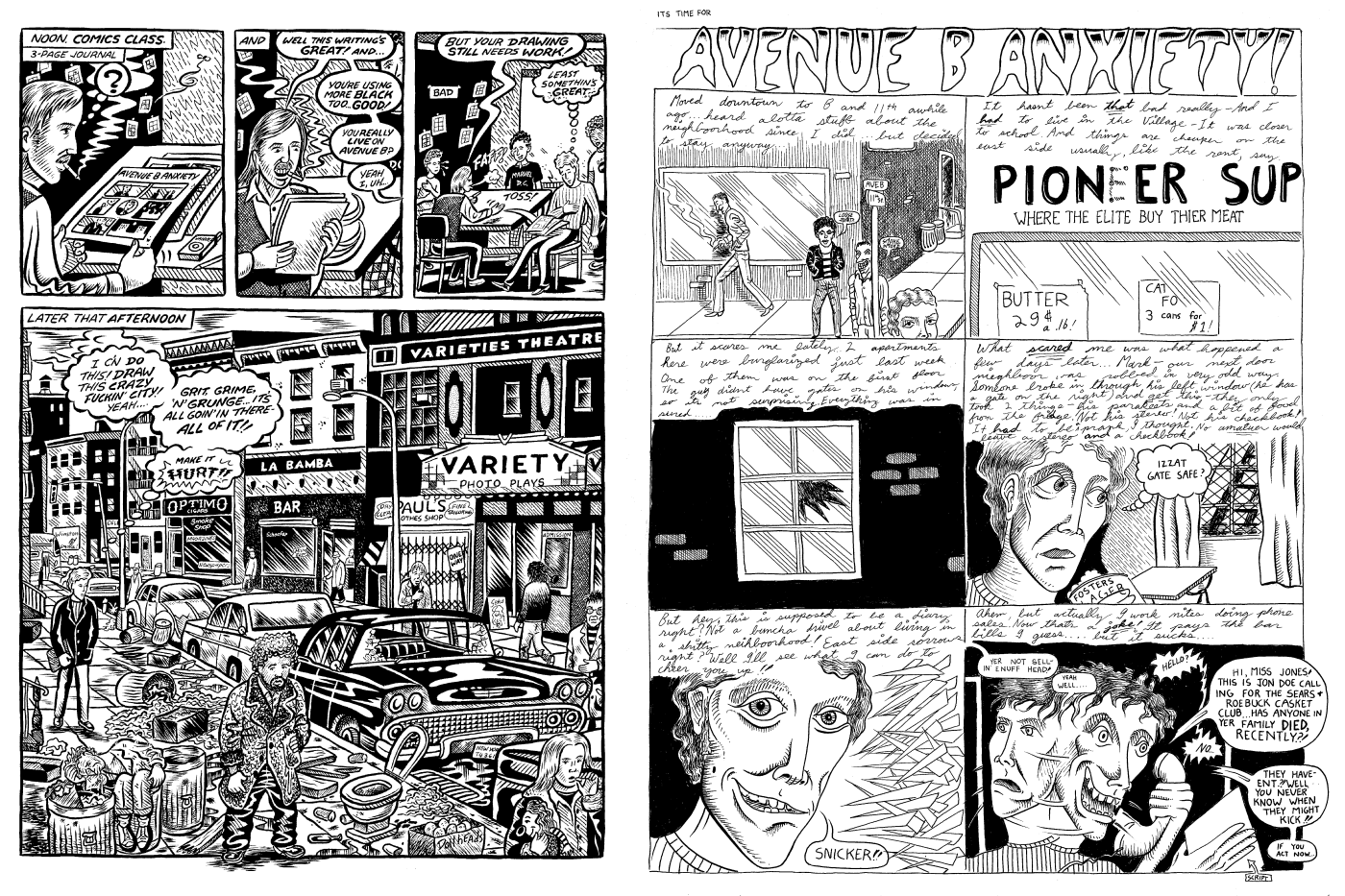

And also in art school you're there to do things that you don't necessarily want to do...like the thing that really got pushed on me early on was autobiography, and it was the first thing I did that got over with him, too, which was a strip about living on Avenue B. Art still knocked it for the drawing, but he said that the writing was great. So you know, I was an art student. You should always be paying attention to what is it that they're telling you what you're good at, and autobiography was what was being pushed on me. So even though I didn't really love autobiography ... back then I wasn't a big Harvey Pekar fan, you know? That was a little bit too dull for me. I wasn't that interested in it. But the whole thing of doing, like urban crime stuff about where I was living, that's something I sort of fell naturally into. So that was the other thing that was good about it, you know? You find your way.

Above left: Glenn's first autobiographical comic, an assignment for Art Spiegelman's class at SVA, as recounted in Asylum. Right: A page from the actual class assignment.

Above left: Glenn's first autobiographical comic, an assignment for Art Spiegelman's class at SVA, as recounted in Asylum. Right: A page from the actual class assignment.How did that come about though? What do you mean by saying they were pushing autobiography on you? Was that an assignment?

There was an assignment where we had to do a three-page journal about what was going on in our lives, right? The only stipulation was that it had to be exactly what happened on those three days. And I immediately broke that rule and just took all the wild, crazy shit that was going on, and put it in those three days, and this is how I continue to work! I would never want to stick to a straight autobiographical narrative. And then the following year, we were putting out a magazine called Bad News, and Art pushed me to do more autobiographical work for that, so I have him to thank him for that. Drawing all of this grimy street stuff.

Mark Beyer's cover for Bad News #3, 1988.

Mark Beyer's cover for Bad News #3, 1988.Yeah, Bad News started at SVA and was kind of ... not a sibling, but maybe an offshoot or a variation or whatever of RAW.

For my money, personally, the early RAW had a kind of self-generated excitement happening in it. In the early issues, if you look at the work by Kaz and Drew Friedman and Mark Newgarden and Mark Beyer, the magazine doesn't feel as if it's completely found itself yet, but it's generating itself and it's evolving and it's finding what it's going to do. A lot of that grew out of SVA because [several of] those guys were students there and so that evolution was exciting to watch happen. It hadn't become hermetically sealed yet, which it was soon to do, in my opinion. They may disagree with this, but as it became more of a polished gem, it was also a lot less like, say, Weirdo. Weirdo allowed for a lot of things to happen — a lot of different artists got in, it had different editors, a lot of different kinds of styles developed. But RAW was always getting more and more polished. This was already in the process of happening by the time I got to SVA in the early eighties and by the time of RAW #3 [1981], there were no SVA students in it. It had Jerry Moriarty's SVA ads, but it was changing. All this coincided with Bad News starting up. I think that Art probably really enjoyed seeing his students develop and come up that way because he is an excellent teacher. Anyone who could deal with him and take his criticism really benefited, myself included. Seeing that development and seeing these artists come together in Bad News was exciting for everyone that was involved in it. And I remember it was referred to by Art as ... Bad News was Panic to RAW’s MAD or something like that. But he was kind of kidding, right?

This is why it's always exciting seeing these kinds of projects happen because it really was a very organic thing that just happened in the class and some of the other art students dropped away and then other people who had already graduated from SVA came in. By this point, Kaz had dropped out, but Mark Newgarden and Drew Friedman, Paul Karasik, too — they got really involved in the second issue and Mark took over the editing for the second issue, and it improved enormously. It had become a very professional anthology by that point and then there was some disagreement between Mark and Art and then it was killed and stopped, which was not good for me, you know, because I knew I wasn't going to get into the RAW, but Bad News was a good magazine for me. There's a lot of really top-notch work in there.

It's very important for projects, especially with a lot of people in them, to branch out, try new things, risk disaster. And when a magazine, a comic, is starting out, it will often take those chances, be adventurous, like with a new band or something. The development, the evolution happens before your eyes, and the novelty is a thrill. The energy, of course, begins to dissipate when things get nailed down. Everything’s been figured out. The evolution stops at this point. Things get frozen in place.

I understand there's an excitement and energy when someone doesn't know what they're doing. That's where creativity comes out of, when you discover that you can do something that you didn't know that you could do.

I think that's when it does happen. I mean, typically, if I'm working on something and I run into all kinds of frustration about it that I just can't seem to get right and I think I'll never get it right, that's the moment where I'm just about to make that breakthrough because I've had to step into some unknown territory that I don't understand. And because of that, I have to find my way into it and when that happens, that's usually when the best work happens because I'm doing something that I didn't know I could do.

Kaz's cover for Snake Eyes #1, 1990. Kaz and Glenn co-edited this important three issue anthology. Courtesy Glenn Head.

Kaz's cover for Snake Eyes #1, 1990. Kaz and Glenn co-edited this important three issue anthology. Courtesy Glenn Head.At some point, Bad News basically evolved into a different thing. Snake Eyes.

Well, Bad News got killed, and I needed to do something. It was that simple. So I stuck my neck out and said, "I'm starting this project!" There was nothing else I could see to do. I'd given up drinking about a year before and needed to focus my energies if I could.

To my great surprise, Kaz got on board, and we became partners in the project. We called it Snake Eyes, and in the moment it was really the best thing that could have happened. Because it forced me to take responsibility for something that had a lot of people contributing. I had to really deal with a lot, making it all happen. Kaz and I both edited it together, but, ultimately, I was the one holding the bag for it. I laid out the book, signed off on each issue.

Glenn and Kaz at a Snake Eyes launch party, ca. early 1990s. Photo courtesy Glenn Head.

Glenn and Kaz at a Snake Eyes launch party, ca. early 1990s. Photo courtesy Glenn Head.So the thing that was really wonderful about editing was that it really put a gun to my head, because in no time at all — first of all, Kaz gets involved and he brings in this great strip called "The Tragedy of Satan." It was like the best thing he'd ever done up to that point, and by this time all these other artists are coming over to my place every weekend practically, like Doug Allen, Jonathan Rosen, Bob Sikoryak, Gary Lieb. You know, a weekly thing with people hanging out and just discussing what we were going to do. It organically formed. I had been somewhat critical of RAW before that — I liked a lot of it, but I thought some of it was kind of pretentious. What Kaz and I wanted was a kind of new American Underground comic, like Zap for the ‘90s. We were looking for something a bit more pulpy than RAW. We wanted something that was more down and dirty. Not "Comics as Art." Comics are already art. That was how we looked at it. And we wanted to get the best new cartoonists on their way up, and that would include Mack White, Roy Tompkins, Brad Johnson, and some of these other people who weren't that well known. We had that kind of arrogance and desire to really want to do something that was going to be its own thing and have the best work that each artist could do. That's not to say that everything in those three issues of Snake Eyes was great, but it was the very best that everybody in there was capable of. So that was a really big breakthrough for me, in terms of making a comics project happen. It was also my first real dealings with a comics publisher, because I didn't really know how to deal with them.

A Snake Eyes party invite, early 1990s. Art by, and courtesy of, Glenn Head.

A Snake Eyes party invite, early 1990s. Art by, and courtesy of, Glenn Head.I called up Kim Thompson at Fantagraphics because they had published the third issue of Bad News, and it was a funny conversation. I called him up and and asked him how that last issue of Bad News had done and he said, "Bad, which we expected," and it did! So I said, "I guess you probably wouldn't want to do anything else with us," and he was like, "Oh, no, we definitely would!" It was just, you know, he had an attitude like, "This is a losing game, just horrible, but let’s see it!” So that was also very fortuitous because it really got my foot in the door, and I’ve had a good relationship with them ever since. But it was good to be bringing something to them that wasn't just about my ego. It was about a lot of other good artists, too, and I had to be responsible for all of them. It really forced me to grow up.

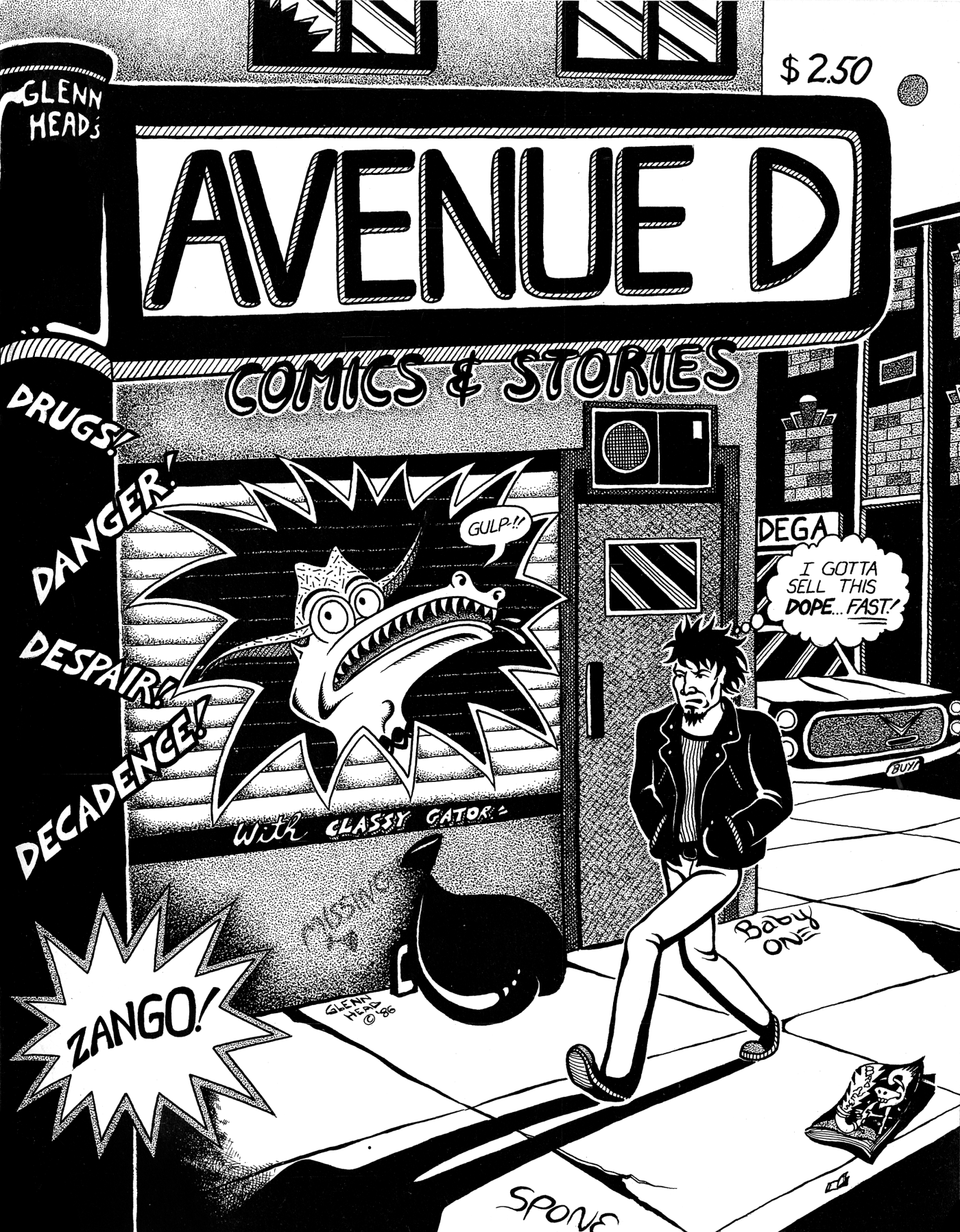

Glenn's self-published Avenue D, 1987.

Glenn's self-published Avenue D, 1987.You would self-publish ...

I had self-published Avenue D...

... that later got re-published by Fantagraphics.

– because I had a foot in the door with Fantagraphics. I was like, "Oh, would you republish it?" And I put some new work in it and stuff like that.

What year was that?

I self-published Avenue D in '87. I managed to get the money together to get it photo-stated and then take it to a comic book printer called X Speedy who did a good print job of it and it was a pretty well received underground comic in it's time back then.

I think I bought it at See Hear [a long-gone NYC fanzine store in the Lower East Side].

Yeah. Probably. They sold both the self-published and the Fantagraphics version. So, for me, I looked at it as, "how am I developing? What's the next stage of the development?"

If you look at the history of autobiographical comics, you can start with Justin Green, then maybe Aileen Kominsky and Crumb himself and a few others, like Harvey Pekar. And then, there's a kind of a gap until people like Chester Brown, Seth, Joe Matt, Julie Doucet and some others created a new wave of them. By that time, your own work was more experimental and psychedelic and surreal and I think your older autobiographical work gets passed over somehow. When Chicago came out, I remember some people saying, "Oh, now he's doing autobiographical work." I was like, wait a minute, he's going back to that work. You were just taking it to a whole new level. I remember Mark Newgarden saying, "Glenn's best work is always going to be about Glenn."

It's a line that I quoted. It's actually in my book Chartwell Manor where, like, I'm showing him something surreal like that drawing, and he's like "It's okay, I guess but I think the best comics by Glenn Head are going to be comics about Glenn Head." And this is one thing I'll say just referring back to art school days: what's really just as important, more important, really than if you have a great instructor, which I did, is hanging out with your peers because Mark would say that kind of thing to me all the time. He was always pushing me much more in the direction of autobiography and telling me that's where I'm going to find my audience, not with the other stuff. So he's somebody that when he talks, I'll listen. I take him seriously.

He’s had me come into his comics classes at SVA and lecture about my work. And one thing I really push the students on is the importance of listening to criticism and suggestions they might not want to hear.

When Kaz and I were working together on Snake Eyes, he was very tough-minded. We didn’t always get along, which was unfortunate because there should have been more Snake Eyes, maybe six issues instead of three. It was like the Velvet Underground, a band that couldn’t stay together but released some good shit that had a big influence on the people who heard it. But he said something to me I always remember and it really hit home, He was telling me, “You've got this way of looking at it like this is an autobiographical comic and this is a surreal comic and what you really need to do is find a way to merge the two of them together.” And it was really an almost profound point that I kept in mind. I didn't really know what to do with that advice when he said it, because we weren't always getting along, but it was very valid and when he said it I just thought, well, you know, “Crumb does Fritz the Cat and then he does an autobiographical comic, so what are you talking about?” But I think he was really right and I do try to blend the two in some of my more recent autobiographical work. With the memoirs, I'm not interested in the mundane. I'd rather there be some level of comic book excitement going on in my autobiographies and that's probably why what I have to start with is a really engaging story. I'm not interested in documentary, not interested in journalism. I'm really trying to capture the psychic state and depict the feeling of what the experience was, to have the surreal elements really capture the truth of what’s going on beneath the surface.

Yeah, with your early autobiographical stuff, which were about where you were living at that time – the dirtiness of the city and dangerous situations that you put yourself into — the drawing style is much more gritty and appropriate for the stories you were telling.

I think the limitations of my drawing ability may have worked somewhat to my advantage. When you’re first finding your voice, there can be a crudeness to the work that communicates directly. An immediacy.

And as you expanded through that period of time, and go back to that earlier era of life, it's informed you as you've grown as an artist so it all comes together. It's been pretty wonderful to watch. And it's great that it happened, and that you've continued. Not everybody continues, right?

They don't. That's one thing I think about too.

Or they go off and do other things. And you can wish they were still doing comics, but it's their life. It's pretty cool that Kaz, for instance, was still doing comics for at least a few years after he started working on SpongeBob. I wish he still did them, but ... he sure did plenty of them.

The thing about his work is that it was so wonderfully creative that it seems like a real loss to not see more.

I agree.

I really feel like he was one of the very best cartoonists doing good work in the 1990s. For my money, he was the best thing in Snake Eyes and he was also a really good editor. He brought in a lot of people I wasn't aware of. And that's why it was weird that we we didn't get along, because we were always happy with what we ended up with, but it was just maybe a clash of personalities or something. I think that there's a real tendency for cartoonists to quit at various times because, if you go with the idea that a cartoonist is a writer who draws well, writing all the time is not living. So you think of a cartoonist that is at a drawing table and they're chained to it and they're working all the time, that's not living. So somewhere, usually between the ages of, say, 20 to 35, a cartoonist will quit for years at a time just because they have to go out and do other stuff. It's really hard to stay focused and to continue to do your best work.

And it's not an easy way to make a living. And we're living in a different time compared to when you guys were doing Snake Eyes and things like that. Back then people could sustain themselves as an artist by doing commercial work and illustrations for alt weeklies and magazines.

Yeah, and all of us were doing that stuff back then. One of the best things to happen to Snake Eyes was to get somebody who was a sort of fine art/illustration person like Jonathon Rosen. He didn't have a comics background so his attempt at doing comics was slightly off and weird, but it was cool and it didn't look like anything else. Kaz gets the credit for bringing him in. Kaz was terrific that way. Into a lot of weird music and films I wasn’t yet aware of. So you could get people from different worlds that might also do interesting comics. The time you're describing, I think it began to completely tank by the end of the '90s, because that's when the dot com bubble burst. And there were all these magazines that had been around forever and everybody was doing illustrations for them. Everybody was getting work and the money was there and rents were still reasonable.

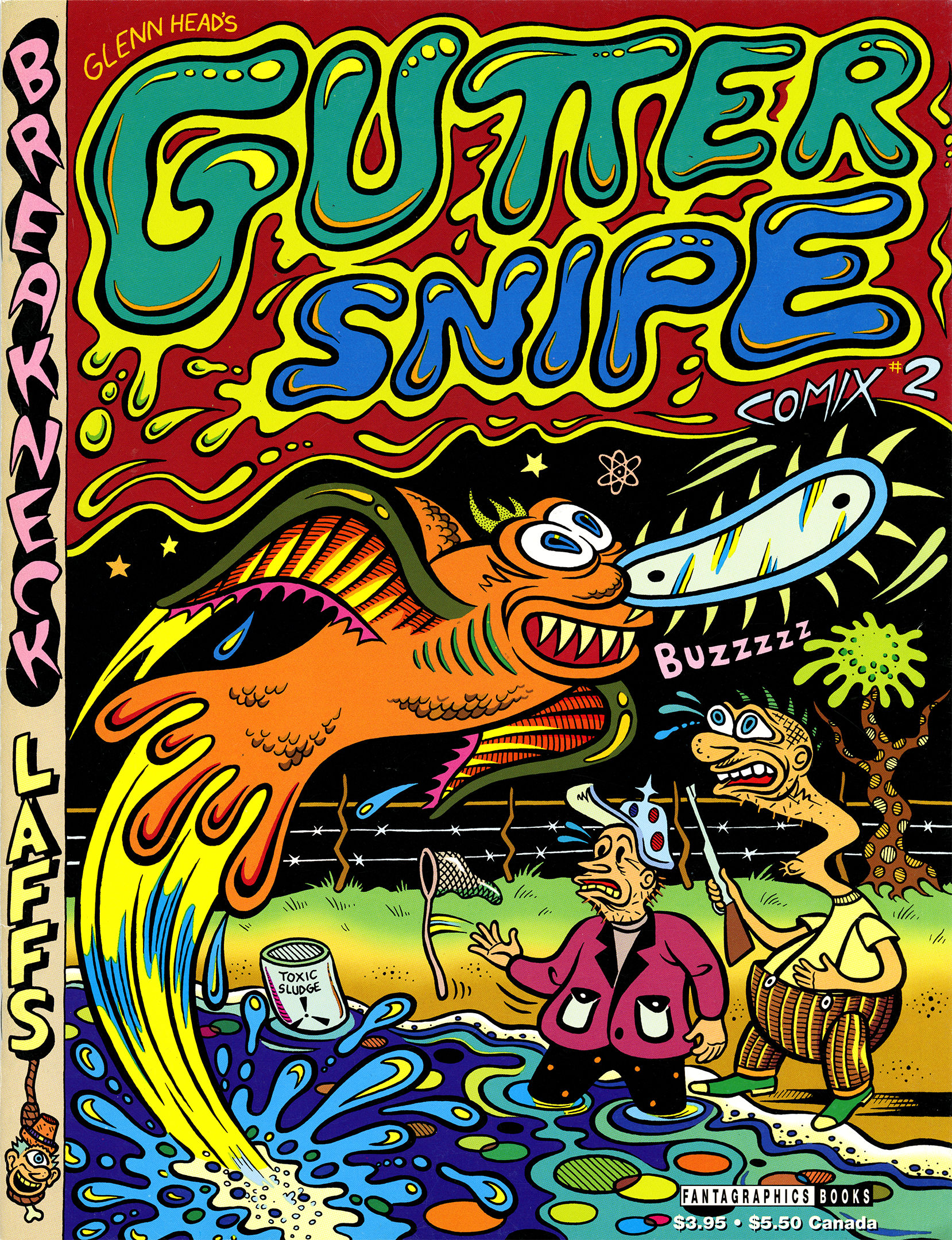

Glenn's art for the cover of GUTTERSNIPE #2, 1996. Courtesy Glenn Head.

Glenn's art for the cover of GUTTERSNIPE #2, 1996. Courtesy Glenn Head.It's just a different world. Today, people are using multiple platforms for sharing their personal stories.

The whole idea was that you were always trying to evolve, to get to the point of making it into a legitimate publication of some kind or other. You're always doing that. At SVA, you learned how to do an eight-page comic where, you know, you folded it over and you stapled it, and each page was a panel that was a book, and you try that and then move up that ladder from there. For most of us, it became almost unconscious that that's what you were trying to do. The point was that as your work developed and you were going to be taking criticism from your peers while you were doing that, and as it developed you would move further along and get into better publications, the pinnacle being, say, RAW or Weirdo. And then at some point, you'd collect enough of your work into one book and get that out and continue to develop. I'm not sure that anybody doing this Instagram stuff is necessarily looking at it like that. I've heard of art students speaking about their work as a kind of therapy, which I can't imagine because, basically, what I was referring to was essentially a kind of ambition. Which isn’t to say Chartwell Manor wasn’t cathartic, but it was also ambitious! People back in the day really wanted to get their work out there.They wanted to be the next whatever. They weren't sure what it was going to be, but they wanted to be that. I don't know if that's how people look at it now. I'm not sure how they look at it, but I don't get the impression that they look at it the way we did.

It's interesting. We were talking about competition before, how healthy competition can create great work. I wonder if that exists anymore? If your ultimate end game is self-publishing something online, what are you competing against? Likes and followers? Algorithms?

I don't know. Ultimately, you're always competing against yourself. I'm always looking at the new book I'm working on in terms of how it relates to the last one. Is it better? Hopefully, a lot better. That's how I really look at it. With my last book, I was drawing about my childhood experiences and boarding school and how it affected me and and how it affected my adult life and I had to get that right. I waited a lot of years to draw that, so I couldn't afford for any of it to not be exactly as it happened and as I wanted it to be and for the art to be the absolute best it could be. So, you know, I can't see doing this stuff just for fun. I just can’t. I find the more of myself I put into it and the harder I work, well, the more I can do.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·