Greg Hunter | November 12, 2025

Note: The following article features sexually explicit images.

How do we read Gilbert Hernandez? The question gets harder, not easier, the more Hernandez adds to his body of work, including such recent releases as Lovers and Haters, the debut issue of Roy (with daughter Natalia), and, from a few years prior, books such as Proof That the Devil Loves You and the collected Blubber. In Gilbert’s craft, longevity, and the distinctiveness of his characters, he’s easy to pitch as a great American cartoonist. And yet compared to other canon-bound comics makers, he’s a slipperier figure. His projects across the years and the effects of his cartooning — what works and why — are harder to capture.

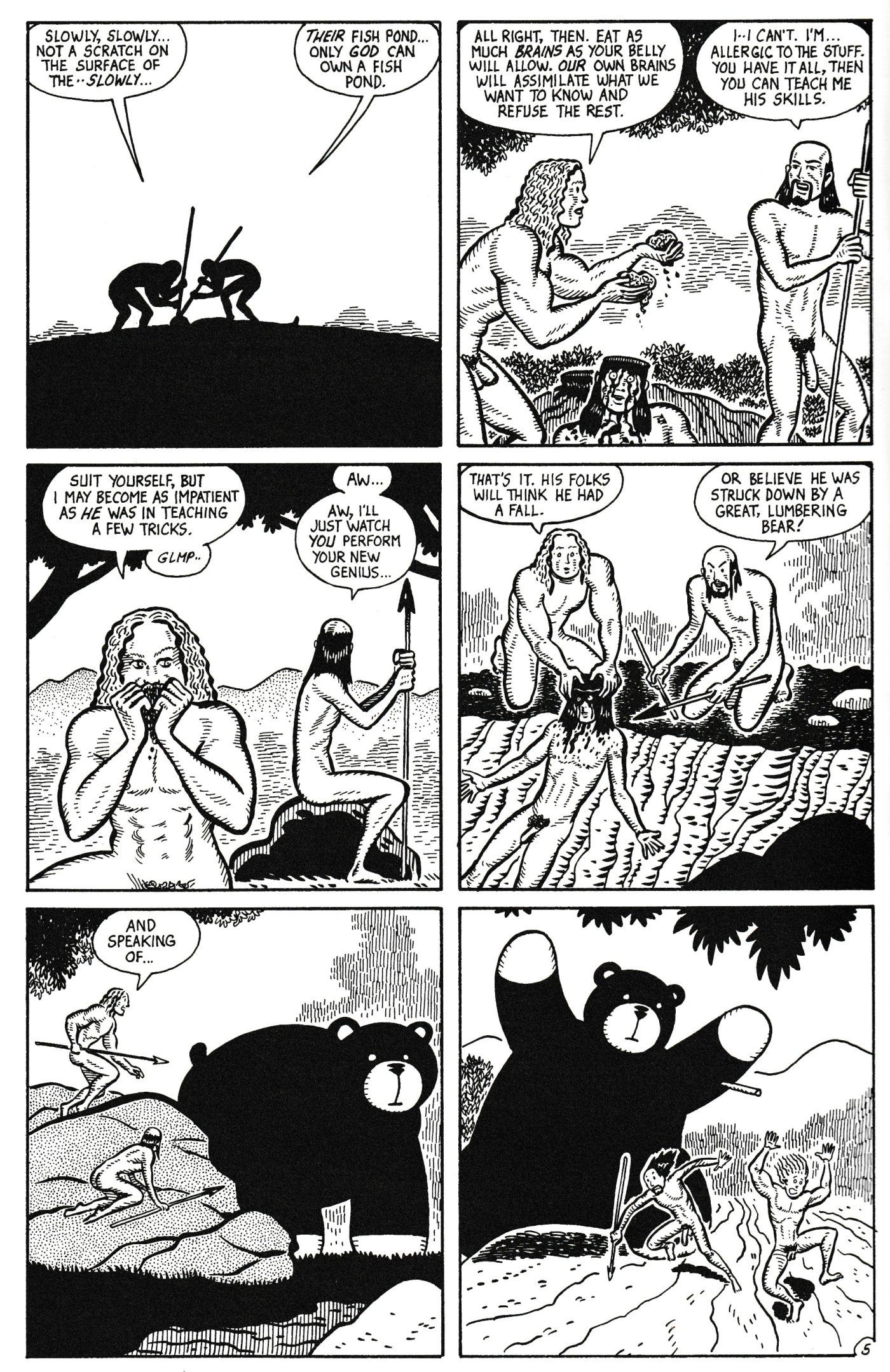

From Lovers and Haters.

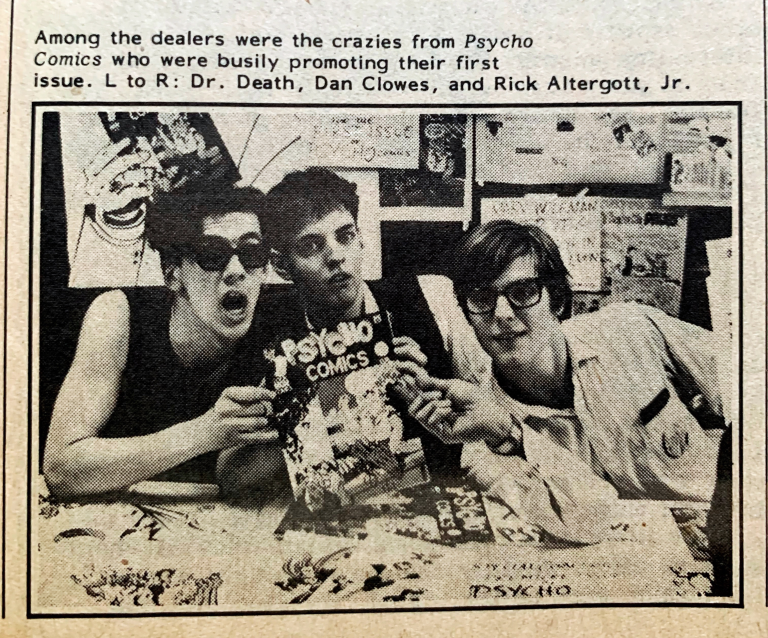

From Lovers and Haters.Gilbert’s work has a density achieved over issues and years. His designs as an artist aren’t legible in the way of Chris Ware’s schematics of despair, to name one cartoonist who emerged in the decade after Love and Rockets launched. Nor do Gilbert’s comics fit as smoothly into a fine-arts context as those of Gary Panter or C.F.. In its directness of meaning and mainstream visibility, his work is far from Alison Bechdel’s, and — turning to folks with roots in the underground — has no signature standalone piece equivalent to Art Spiegelman’s Maus. Robert Crumb is a useful reference point, both in the spread of Crumb’s comics across anthologies and decades and in exposure to the cartoonist’s id. But, as this piece will cover later, there are limits to the Crumb comparison.

All of this matters — the ability to locate Gilbert relative to peers and traditions — as far as keeping an artist’s work read and circulating matters. Context, however reductive it can be, shapes the support beams of cultural memory.

Surveys of Gilbert’s work tend to mention his brother Jaime, the other most frequent contributor to Love and Rockets. In understanding what Gilbert does, we might call recognition of the brothers’ shared project — the overlap between their achievements — necessary but not sufficient. The Hernandez brothers are comics heavies individually and as a duo, something like a miracle in the medium. Fans rightly celebrate their depictions of queer people and people of color, with special attention to Jaime’s Oxnard-esque Latino enclave Hoppers and Gilbert’s Central American community of Palomar. This, too, is a necessary but not sufficient way to assess Gilbert’s work, especially the provocations of his later comics.

A 2022 episode of PBS’s Artbound is a recent, typical, and particularly visible example of how Love and Rockets is discussed. Speakers move between the language of representation and the language of craft, outlining the impacts of both in the brothers’ works. A viewer could do a lot worse. And yet the documentary’s omissions will be conspicuous to anyone who has kept current with Love and Rockets. It avoids the most transgressive of Gilbert’s works completely, and is comical in how unprepared it would leave a reader for a volume of the comic released in the last fifteen years.

The documentary begins with the brothers noting that they’re doing some of the best work of their careers, to less attention. Then, it foregrounds the groundbreaking first decade of L&R, with more time on the brothers’ D.I.Y. origins than their perseverance through middle age. Some of this is generic convention — with a one-hour arts doc, you get what you get — but the view of Gilbert is most impacted by the narrowness of scope. Jaime, while an idiosyncratic artist in his own right, continues to produce work that a reader can comfortably approach via its skillful depictions of culturally bounded lived experiences. (The documentary’s discussion of recent L&R comics focuses on the aging of Jaime’s character Maggie and her peers.) Gilbert shares his brother’s positionality, but his works form an uncertain terrain, often grotesque and hypersexual in a way sources like the Artbound retrospective neither condemn nor acknowledge.

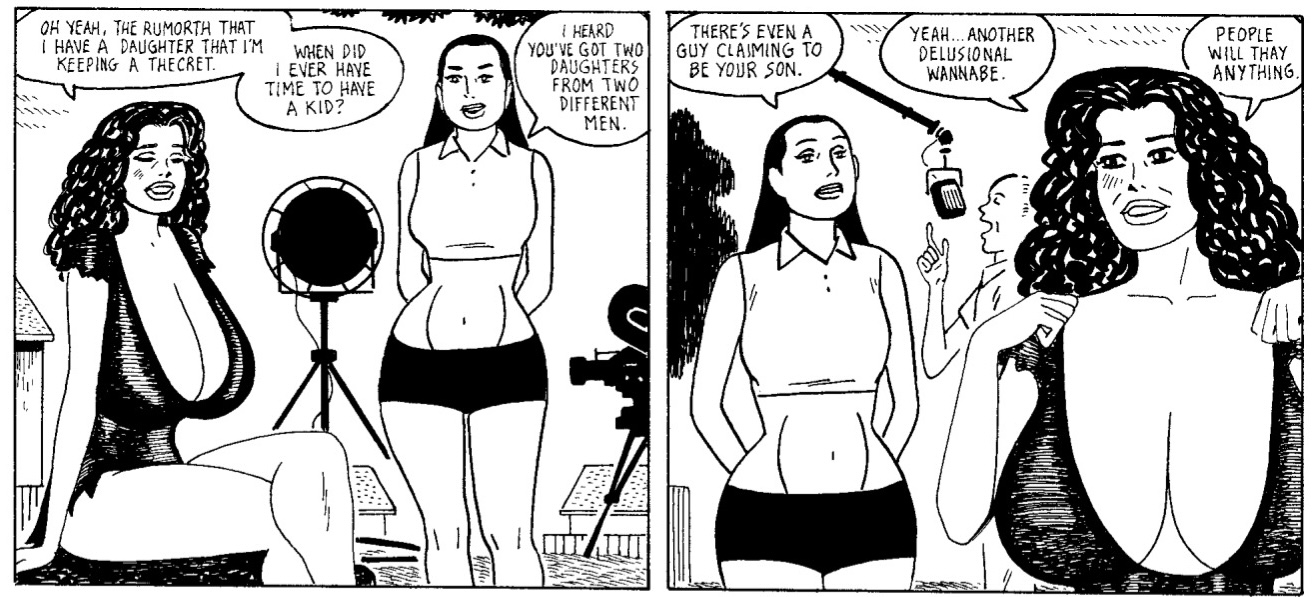

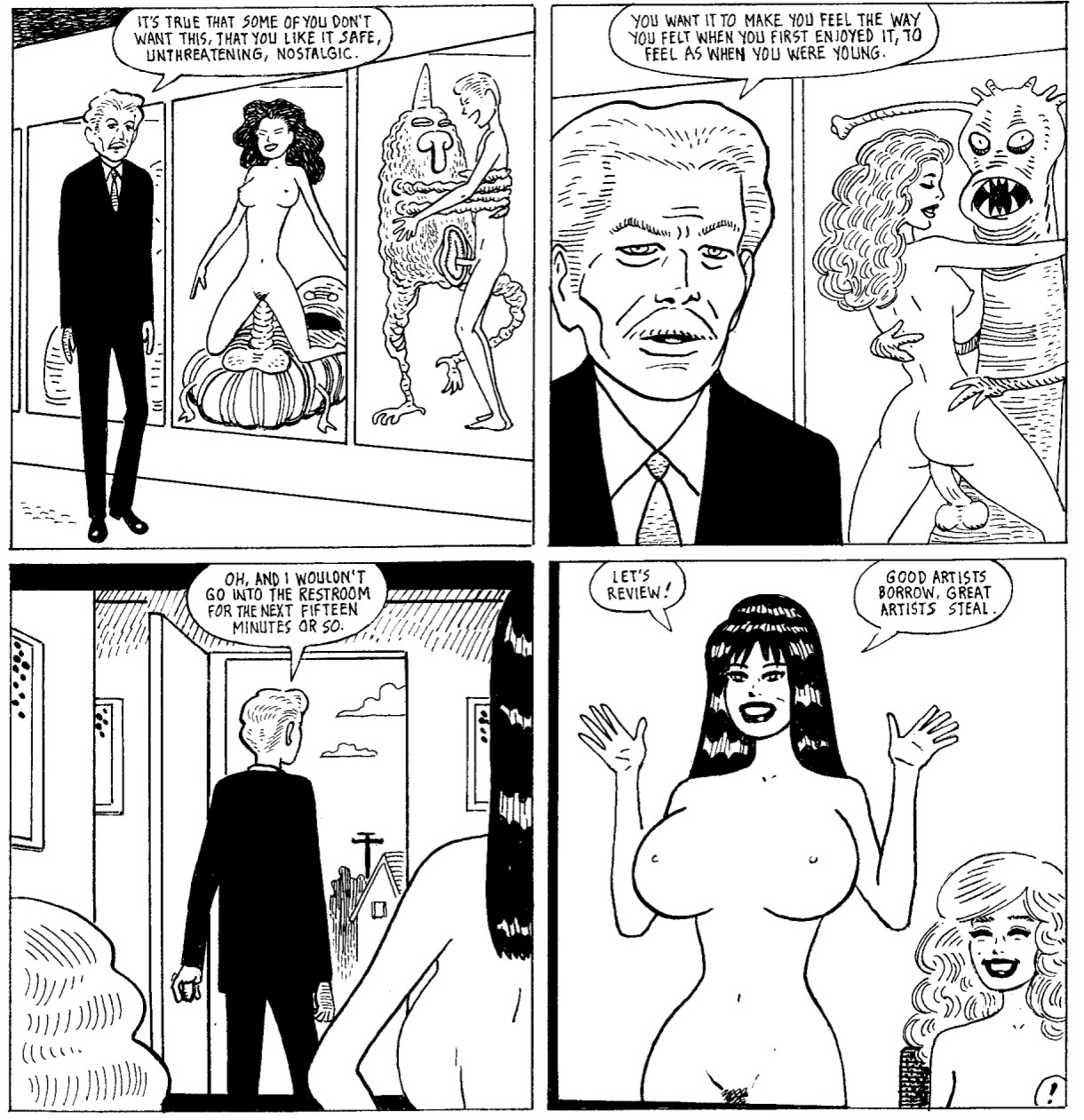

From Lovers and Haters.

From Lovers and Haters.Lovers and Haters, a collection pulling from Love and Rockets and Gilbert’s solo anthology Psychodrama Illustrated, is the latest book-length release to feature Fritz, his most prominent character of the last two decades. A sister to Gilbert’s earlier creation Luba, Fritz is also a psychotherapist turned B-movie icon, with a variety of adult performers in her orbit. Many of these figures, chasing Fritz’s star, have had elective surgery to transform their bodies, with extreme results and roles in fetish entertainment. To consider Gilbert’s renderings of these characters is to consider, in microcosm, the challenge of locating him as an artist. His comics are self-aware about the heightened anatomies of his figures, to the point of addressing them on plot level, and yet leave a strong impression that this is just what the guy’s into. Nor is the language of sex- and kink-positivity a match in an uncomplicated way. If the misogyny of R. Crumb is absent, Gilbert remains engaged in objectifying these figures. Still, there’s an attention to Fritz’s interiority that a cartoonist like Crumb never sustained in his objects of desire.

From Lovers and Haters.

From Lovers and Haters.Throughout Lovers and Haters, readers see people attempt to impose their wills on Fritz and her imitators. They are reliably small, seedy men. In other words, the comics address objectification at plot level too. This is not math — an in-story critique does not negate process — and so feeling the discomfort of contradiction is part of the reader’s experience. And readers find other contradictions in Gilbert’s recent releases: violence and play, abrupt swings between the silly and the serious. He’s working in irreconcilables, more and more so. For a lens that captures these tensions, we can look to, and through, a late style.

The origins of the late-style concept are appropriately fragmented: originating in the writing of Theodor Adorno, popularized by Edward Said, and further codified from Said’s lectures and essays after his death, resulting in the collection On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain. Like the final girl of Carol Clover’s Men, Women, and Chainsaws, the idea has gained a foothold in the culture and lost some of its shape in the process. The Said of On Late Style emphasizes an older artist’s consciousness of mortality, with particular attention to how “their work and thought acquires a new idiom.” The cases Said cites tend to include "intransigeance, difficulty, and unresolved contradiction” — works of disharmony that “leave the audience more perplexed and unsettled than before.” (Recent examples outside of comics arguably include Lou Reed’s varied, vexing final albums and the anti-nostalgia of Twin Peaks: The Return.)

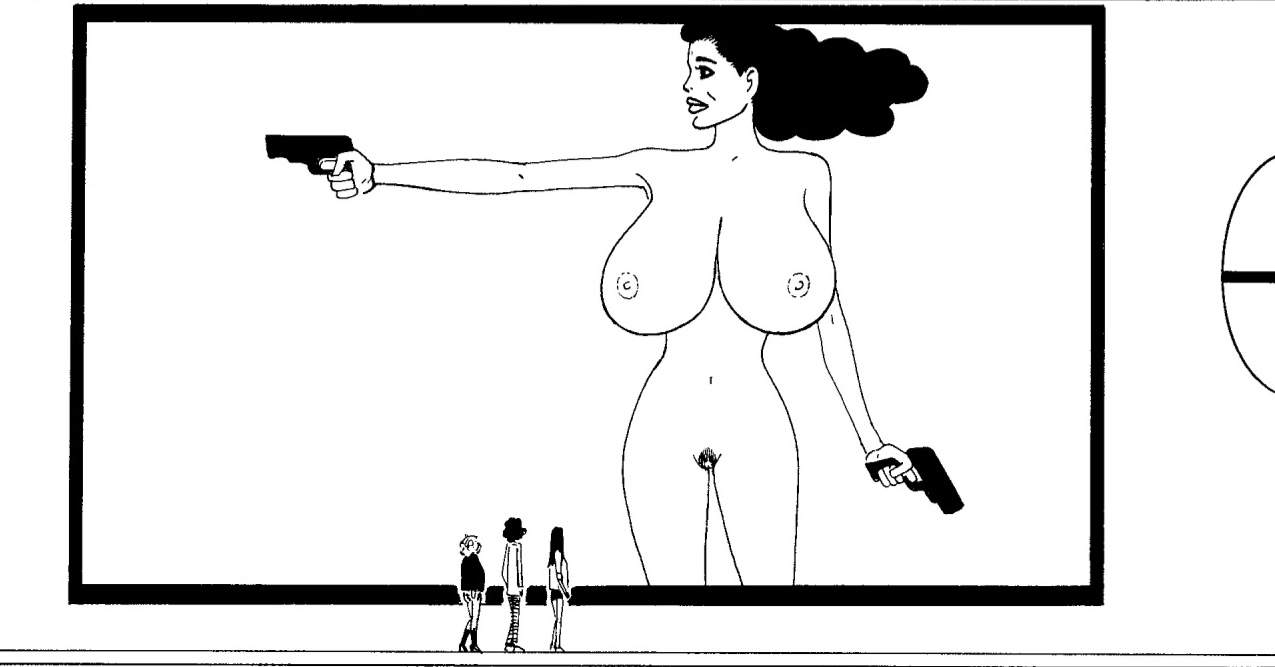

A sequence from one of Fritz's exploitation movies, as seen in Lovers and Haters.

A sequence from one of Fritz's exploitation movies, as seen in Lovers and Haters.Taking after Adorno, and citing Adorno’s writings on Beethoven, Said describes a form of exile for the late-style artist: a “contradictory, alienated relationship” with the established order. In the case of Gilbert Hernandez, the PBS documentary on Love and Rockets provides an unintentional staging of this phenomenon. Gilbert exists in a kind of compartmentalized exile, with parts of his bibliography already treated as legacy, celebrated in his lifetime, and parts ignored entirely. “For Adorno,” Said says, “lateness is the idea of surviving beyond what is acceptable and normal,” and if there’s a satisfying frame for the Gilbert of the last decade, it’s this.

The irreconcilables of Gilbert’s work form a vein throughout Lovers and Haters. The book’s publisher, Fantagraphics (also the owner of this website, etc.), once had an imprint, Eros Comix, devoted to pornography — and thus an institutional divide between sex comics and comics that might involve sex. With their sex scenes and eroticized nudes, Lovers and other Fritz releases can resemble cheap-thrills erotic fare (less so the tender crowdfunded-anthology kind of recent years) and for certain readers probably function just fine that way. And yet they resist the kind of categorization Fantagraphics once practiced, with a degree of difficulty a reader would not expect from a sex comic typically conceived. A disorienting doubling occurs, challenging readers to differentiate the variety of Fritz imitators. Gilbert also makes abrupt shifts in time, meeting his characters at different points across years; it’s on readers to catch up. Even set against other works that blur genre lines, such as the horny surrealist manga of Shintaro Kago, the Fritz comics don’t wrap up as neatly.

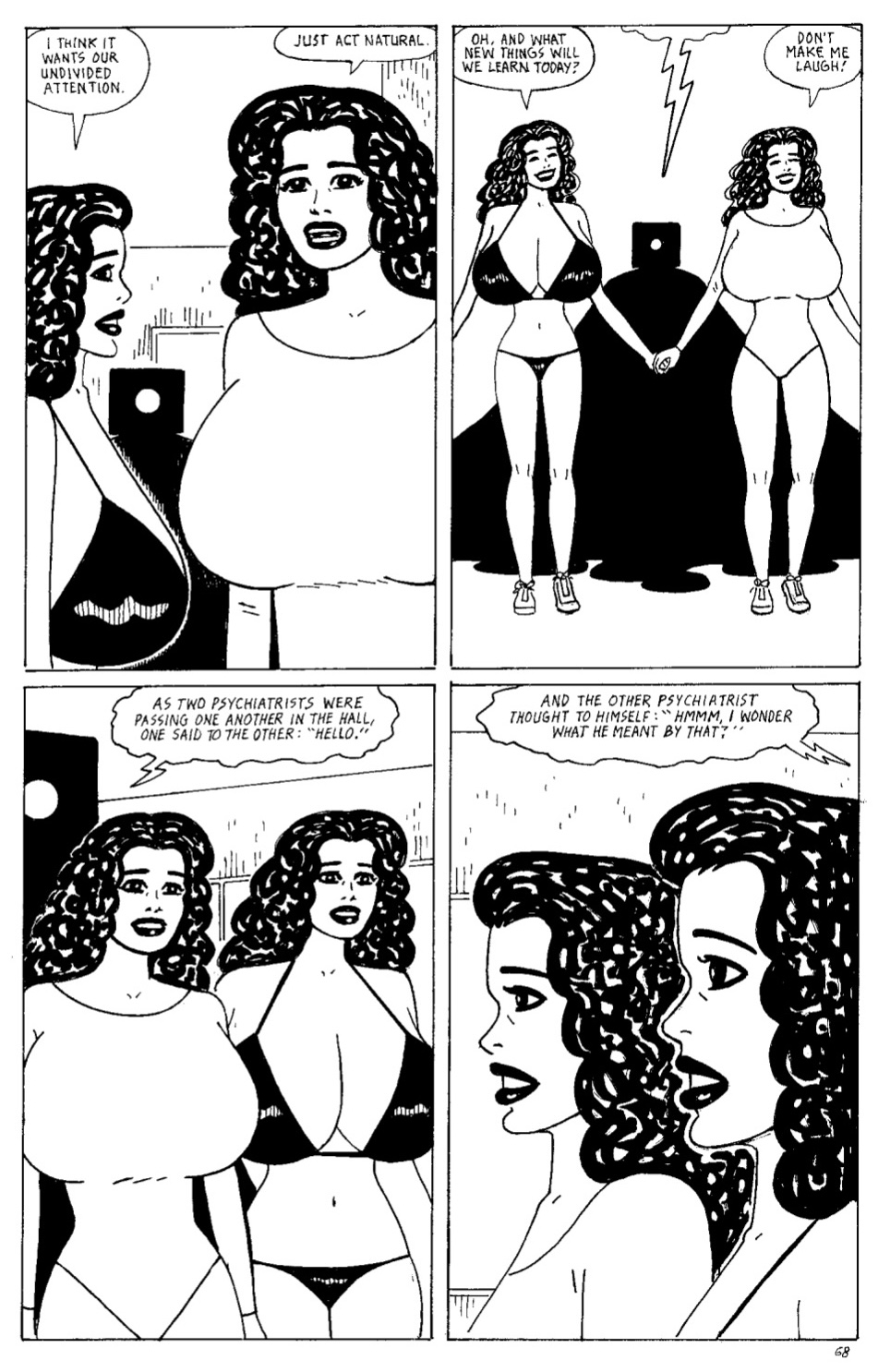

From Lovers and Haters.

From Lovers and Haters.Because of the settings in which many of Gilbert’s characters operate — sex work, low-budget films — discussing his comics as late works brings to mind similarities between the language of late style and the language applied to exploitation media. Said and Adorno stick to elevated examples, and to group Beethoven with Lloyd Kaufman would be to ignore the way On Late Style analyzes artists with control of their craft, at the edge of their medium. Yet there’s still room to observe a cross-cultural rhyming here. Adult- or B-movie makers exist, as Said says of late artists, in their own “kind of self-imposed exile from what is generally acceptable.”

Some of the effects of exploitation storytelling — confusion, repulsion, fatigue — may result from technical or financial limitations, not grappling with mortality. And Said’s analyses explore the routes on which artists pursue late works, i.e. their applications of craft, as much as the results. But in considering Gilbert’s recent comics, layering the lens of exploitation atop the lens of late style has a powerful clarifying effect. He’s making art in the intersection, taking exploitation media on the level of subject and setting but also allowing for crassness, puckishness, and brazen sexuality in his artistic mode, while cartooning at an elite level — and all of this against the backdrop Love and Rockets’ accumulated prestige, in a medium with a historically lowbrow profile. Call it latesploitation.

Discussing the late style of a living artist can feel uncomfortably like mourning them prematurely. In Gilbert’s case, let’s hope that a long period of continued creation follows his recent releases. With that proviso set, the way death appears in Gilbert’s recent works aligns with late-style criteria too. Said cites works by director Luchino Visconti (for their themes of degeneration) and novelist-playwright Jean Genet (for the abundance of death imagery) in exploring this area of late style. These works are saturated with death, he argues, even when not engaging with it directly. Earlier, he quotes Adorno making a similar point: “Death is imposed only on created beings, not on works of art, and thus it has appeared in art only in a refracted mode.” Proof That the Devil Loves You, one of Gilbert’s recent releases, engages in this kind of refraction.

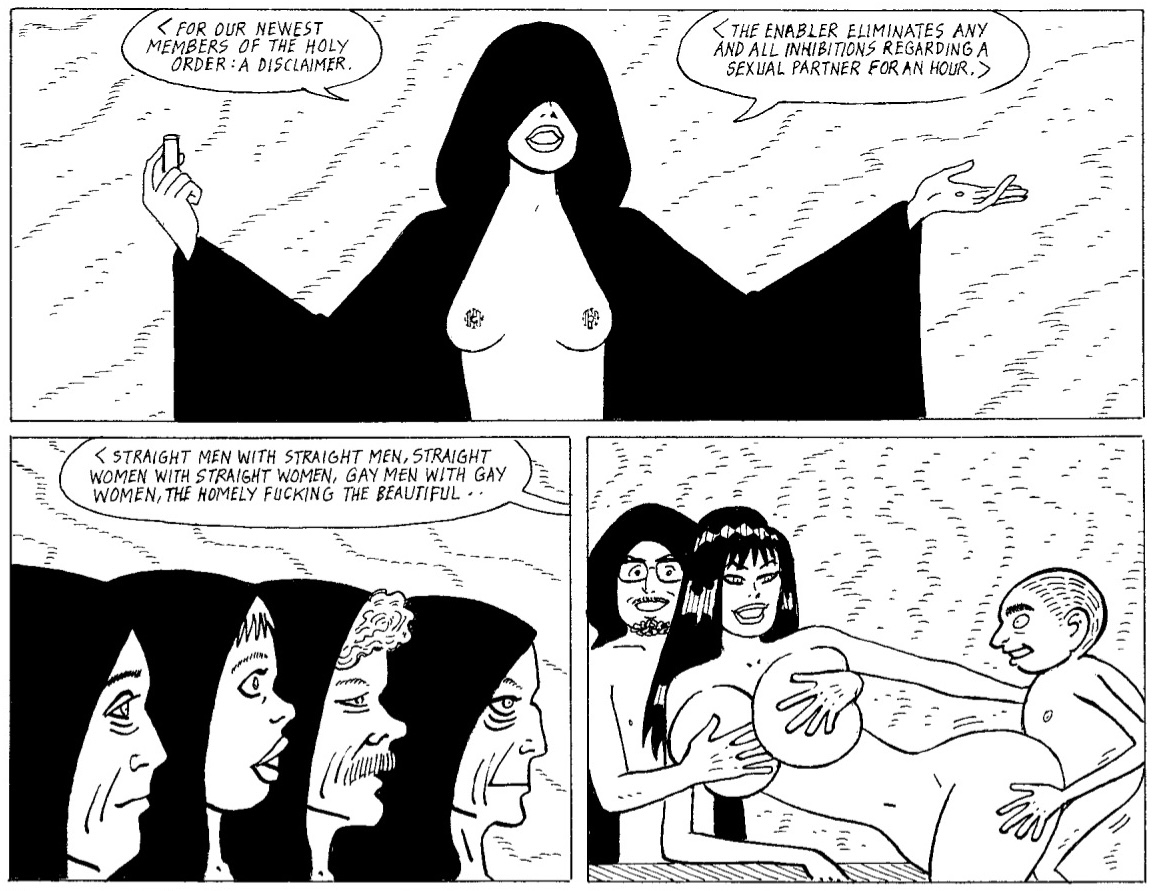

From Proof the Devil Loves You.

From Proof the Devil Loves You.The book depicts moments from Fritz’s fictional filmography but closes with Fritz, off camera, reflecting on aging as an actress. Before that, Proof sends readers on a dreamed or remembered journey across multiple Fritz movies, including a surreal meeting between multiple Fritzes as they attempt to find their places within her body of work. Only at the end does the book reveal Fritz’s interiority as the context connecting the previous scenes. As the design of the book comes into view, so does frank talk of decline. In its closing scene, the (ostensibly real) Fritz urges a companion, “Let’s enjoy what’s left of our brains.”

The aging of recurring characters is one of the most lauded features of Love and Rockets, and one of the most self-evident ways Gilbert’s work addresses mortality. What’s useful, even energizing about applying late style to Gilbert is that his non-L&R projects — often unserious, sometimes baffling, superficially dismissible — begin to seem almost essential. In Blubber, Gilbert runs cartoony, made-up creatures through violent and/or sexual comedic vignettes against spare fantasyland backdrops. There are traces of Looney Toons, Krazy Kat, nature documentaries, and Tijuana Bibles. The result is easiest to categorize as the artist blowing off steam, Gilbert at his least concerned with legacy. Most notably for this piece, life in Blubber is cheap. Death is always just around the corner — probably following an encounter with a giant phallus.

Death is not strictly diffuse in Blubber; it is scattered the way buckshot scatters. But it exists in an atmosphere of irony and unreality. This too suits a reading of recent Gilbert comics as late-style creations. Said, citing Adorno on Beethoven, describes how death appears as irony in such works. Across the landscapes of Blubber, it wears a willfully unserious guise, within perversions of midcentury children’s entertainment, and it’s everywhere.

Blubber’s ironical treatment of death intersects with sex in face-value ways — again, there’s plenty of imaginary monsters being crushed by penises or burned by scalding ejaculate — but also through Gilbert’s larger approach. In collected form, the comic’s slapstick sex scenes proceed with such repetition that objects threaten to lose their meaning. With this, Blubber merges sex and death on a level beyond narrative incident, iterating both until it has negated the expected on-page effects. This is another way we might define Gilbert’s latesploitation: he’s pulling from familiar, if transgressive, modes, but with an insistence that pushes scenes to less recognizable places.

Sequence from "The Fabulous Ones," from Comics Dementia.

Sequence from "The Fabulous Ones," from Comics Dementia.Writing about these later works means acknowledging that, yes, Gilbert Hernandez has always made weird comics. Collections such as Comics Dementia and Amor y cohetes include numerous cartooning experiments from outside Gilbert’s usual settings and ensembles. But late style is, if anything, helpful in articulating what’s different about the last ten-plus years. A comic such as “The Fabulous Ones” (from 1996, in Comics Dementia) features nude figures, imaginary creatures, and a fantasy wilderness backdrop, but also has hatch marks and more abundant dialogue that, in a relative way, ground the piece. Throughout Blubber, and more recently the first issue of Roy, Gilbert’s rendering of landscapes and figures is simpler by degrees, though skilled in its execution, with story beats stamped to blunter points. Looking only at Gilbert’s oddball one-offs still takes a reader deeper into the deep end across decades.

Contrasts between earlier and recent works appear in comics with Gilbert’s longtime ensemble too. From a story such as Love and Rockets X (drawn from 1989 to 1993) to the newer comics of Lovers and Haters, readers see Gilbert easing up on narrative density within a given page. He moves from tight nine-panel grids to grids of six or eight panels — in other words, moving compression to expansion. If some of this happens for ease of drawing, the shift is still compatible with the tenets of late style. The idea of late style as a kind of exile allows for a correlation of lateness and space. In this case, we find Gilbert the exile, Gilbert apart, making his own territories, with open skies and other negative spaces appearing frequently across the newer works.

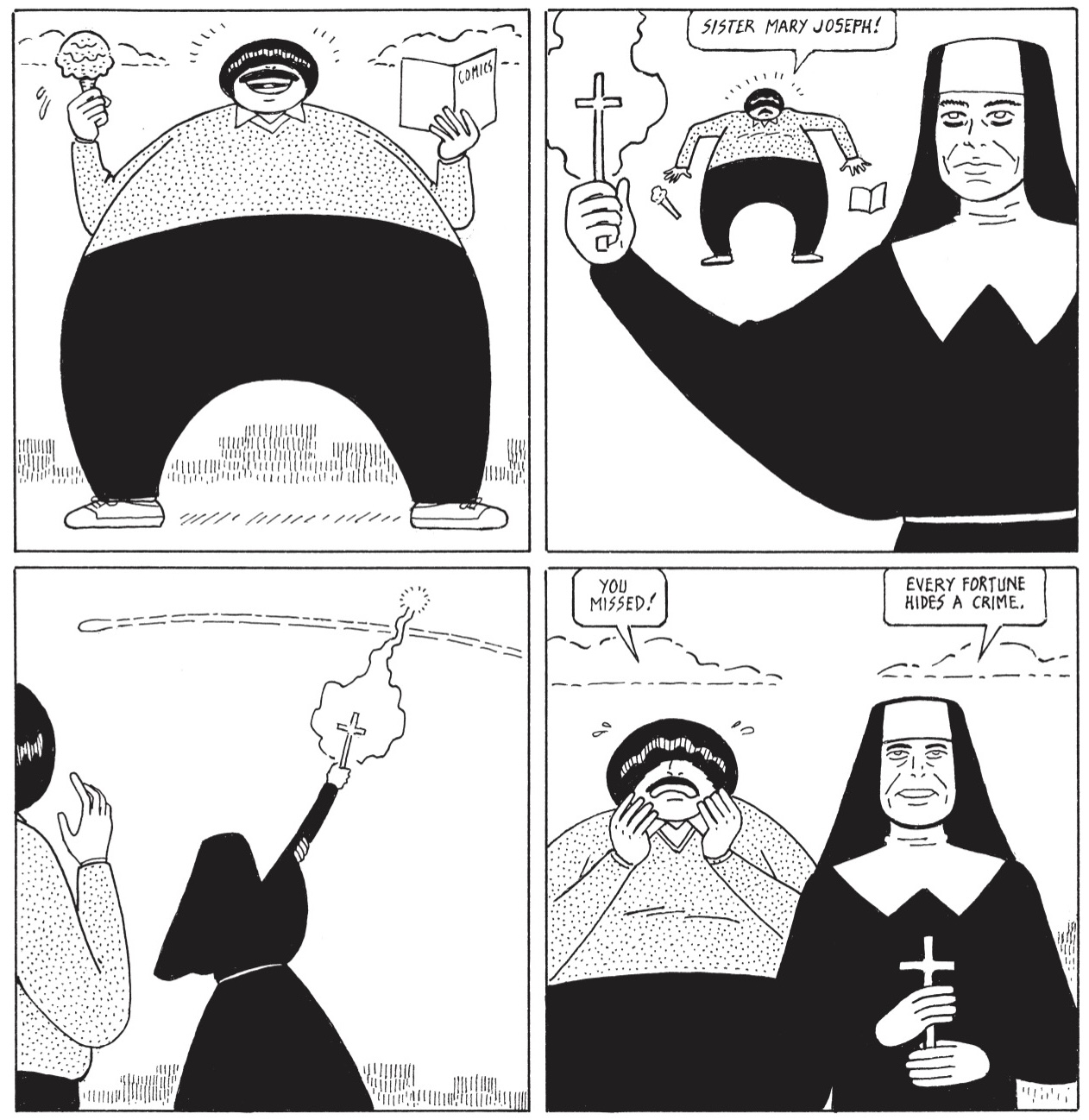

A sequence from "Red Tempest," collected in Blubber.

A sequence from "Red Tempest," collected in Blubber.In his introduction to On Late Style, literary scholar Michael Wood is quick to mention anachronism as a feature of late style, and readers can treat Gilbert’s landscapes as sites of anachronism too. The Hernandez brothers have always synthesized their influences and acknowledged their artistic debts, from Owen Fitzgerald or Dan DeCarlo quotations in their figure drawing to the shades of Herbie Popnecker in Gilbert’s recurring character Roy. In the Hoppers stories, Jaime interpolates sixties kids’-comics aesthetics into an L.A. punk milieu so effectively that it’s easy to take the innovation for granted. Jaime’s gifts include the ability to make these moves look effortless, and to turn a counterintuitive choice into a frictionless readerly experience. Yet Gilbert’s toying with influence is striking and discordant within Blubber. One particularly fetishistic piece, “Red Tempest,” features facial expressions out of Archie comics and a monster that (minus its immense, craggy penis) could pass for a Jack Kirby creature, all folded into a surreal superhero sex vignette.

Sequence from Blubber.

Sequence from Blubber.More so than most moments in Love and Rockets, this comic exists in high contrast, with Gilbert placing anachronistic, silver-age imagery against the unreality of his hypersexual slapstick scenes. To the extent a piece like this achieves some balance, a moment later in the collection disrupts even that. Valus Droog, a character from Gilbert’s Fritz stories, appears midway through Blubber to admonish the reader: “Some of you don’t want this [...] You want it to make you feel the way you felt when you first enjoyed it, to feel as when you were young.” Gilbert’s late comics function like a mousetrap this way — first the bait of nostalgia, then the snap of the impossible return.

It’s arguments like this, embedded in releases like Blubber and Roy, that make these superficially frivolous late works impossible to fully dismiss. For all the provocations of recent Fritz stories, their literary merit is clearer by comparison, and their connections to Gilbert's most celebrated comics is more direct. But in appreciating the range of his current output—the uncomfortable interaction of freedom, amusement, reference, and hostility — Blubber and its ilk are, again, nearly essential.

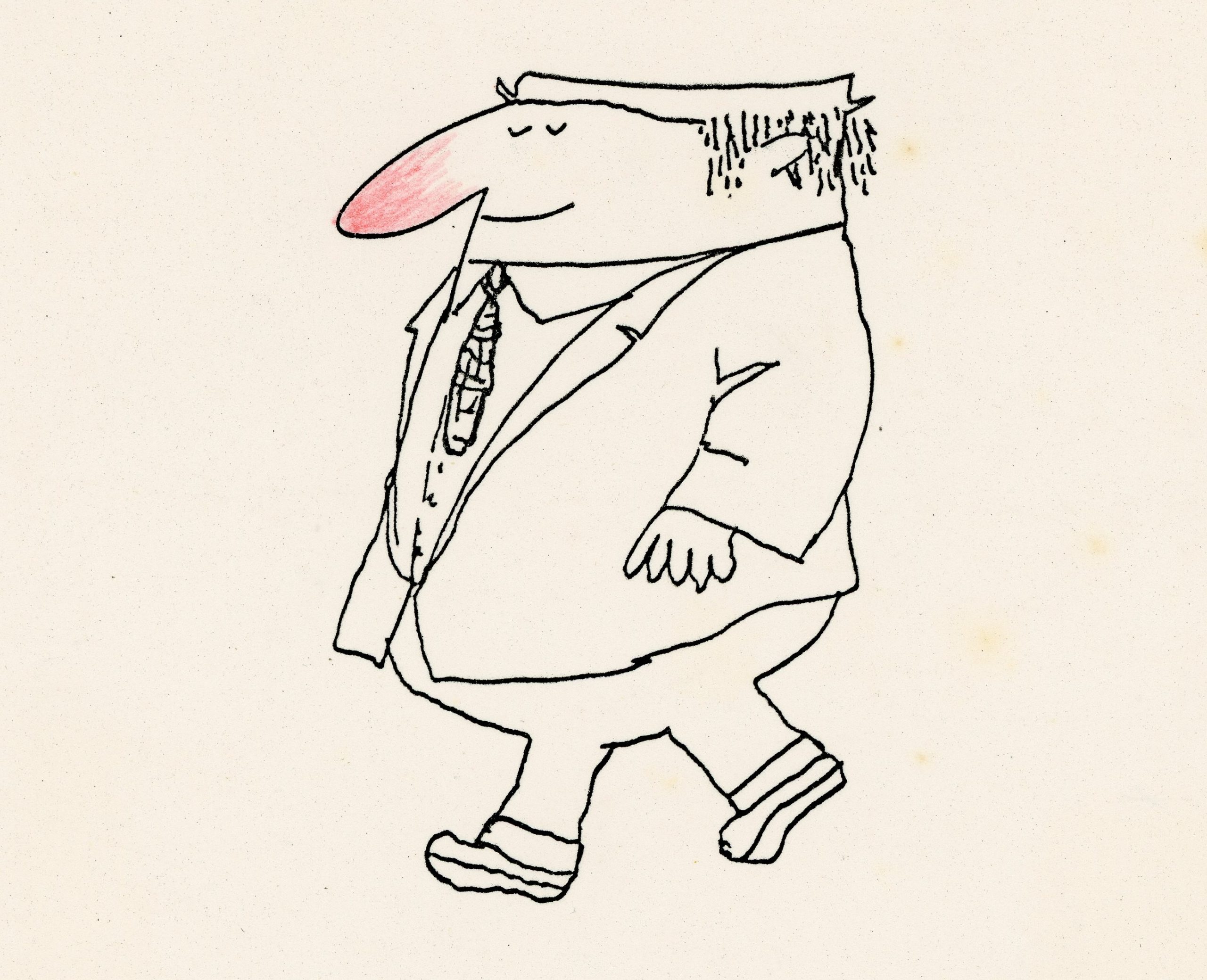

Sequence from Roy #1.

Sequence from Roy #1.A late-style reading of Gilbert Hernandez’s comics does not resolve all tensions in the work, much less suggest that each part is fully effective. Lovers and Haters, for example, has the good and bad of the latest piece in an ongoing project. Readers find the weight of characters’ histories, Gilbert’s unmistakable style, and his trust that they’ll orient themselves to his scenes. But it has an awkward shape as a discrete work — collection seems to exist because it was time for another L&R book, not because it gives the sense of an ending to any part of Fritz’s story. Similarly, readers may see in Proof That the Devil Loves You a compelling puzzle or a long walk to brief moments of emotional directness. And yet these books and others reliably feature moments that are poignant, masterfully drawn, or bracing in their unpredictability.

There’s no one with an output quite like this, not even Gilbert’s brother and longtime collaborator. Nor is it an exaggeration to say the unwieldy shape and unapologetic idiosyncrasies of Gilbert’s output are part of his art, and are staggering for that. He exists lately in, if not a purposeful exile, than the territory one finds while privileging creation over legacy. Late style offers one way to locate him, which is a valuable thing. With Love and Rockets and with Gilbert’s work especially, we already have evidence of how selective the public memory can be. Let’s not be late in navigating his comics, in all their rewards and hazards.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·