Kevin Brown | August 12, 2025

Most lay people know Eadweard Muybridge as the person who took the picture of the galloping horse, if they know him at all. They don’t know about his other accomplishments or where he fits in the context of the technological innovations of the late 19th century, especially in terms of photography and motion pictures. Guy Delisle’s graphic biography focuses on that context, ignoring his younger life, as well as less consequential details of Muybridge’s life, such as his adoption of his name (he was born Edward Muggeridge, and he used various spellings throughout his life—his grave has him as Eadweard Maybridge). Instead, Delisle begins with Muybridge’s first trip to the United States, then follows him until his death, but he also drops away from Muybridge at times to show what his contemporaries were also doing, especially when they were building on his work.

Most lay people know Eadweard Muybridge as the person who took the picture of the galloping horse, if they know him at all. They don’t know about his other accomplishments or where he fits in the context of the technological innovations of the late 19th century, especially in terms of photography and motion pictures. Guy Delisle’s graphic biography focuses on that context, ignoring his younger life, as well as less consequential details of Muybridge’s life, such as his adoption of his name (he was born Edward Muggeridge, and he used various spellings throughout his life—his grave has him as Eadweard Maybridge). Instead, Delisle begins with Muybridge’s first trip to the United States, then follows him until his death, but he also drops away from Muybridge at times to show what his contemporaries were also doing, especially when they were building on his work.

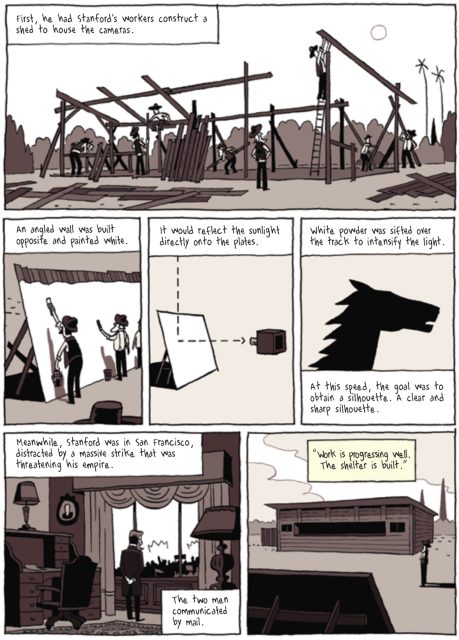

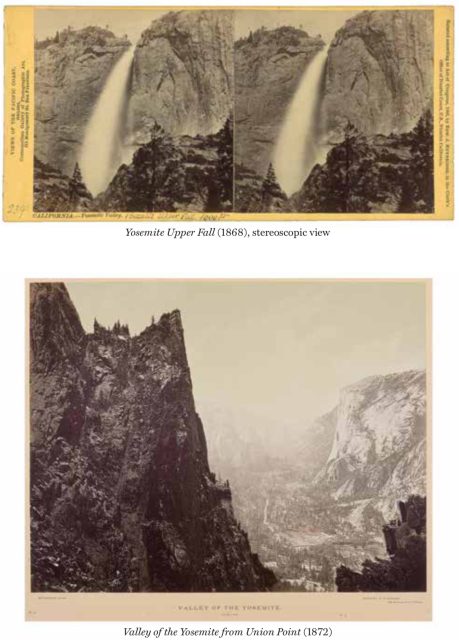

Muybridge’s most famous development—the ability to capture a moving object at a particular moment in time—takes up the first half of Delisle’s biography. He shows how Muybridge came to the U.S. to make his name, tries his hand at bookselling, learns about photography, sustains a serious head injury, returns to England, then comes back to the U.S., all in a few pages. The head injury seems to change Muybridge’s personality, which leads to a moment early in Muybridge’s life that could have changed not only the course of his life, but that of the technological innovations he’s responsible for.

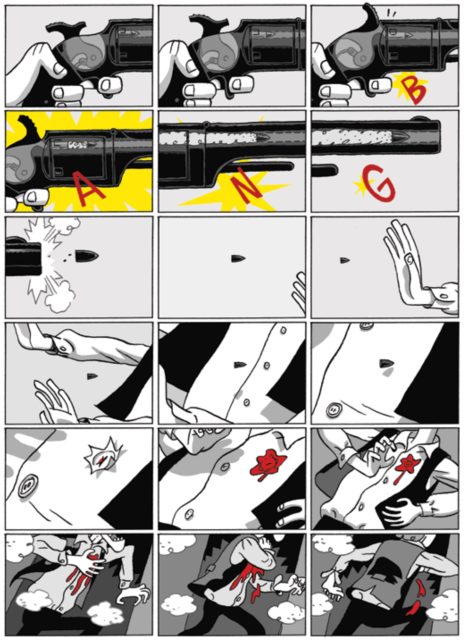

Muybridge had married when living in England, and was often away traveling to the U.S., leaving his wife alone. She began seeing another man, and, when she gave birth to a child, Muybridge believed it wasn’t his. Delisle does point out that everybody who saw the child, whom Muybridge put in an orphanage, looked like Muybridge, further questioning Muybridge’s actions. He becomes outraged, so he kills the man. However, he is found not guilty, not due to insanity, which was the defense lawyer’s strategy, but because it’s "what a man would have done at the time", such was the reasoning the all-male jury gave in their decision.

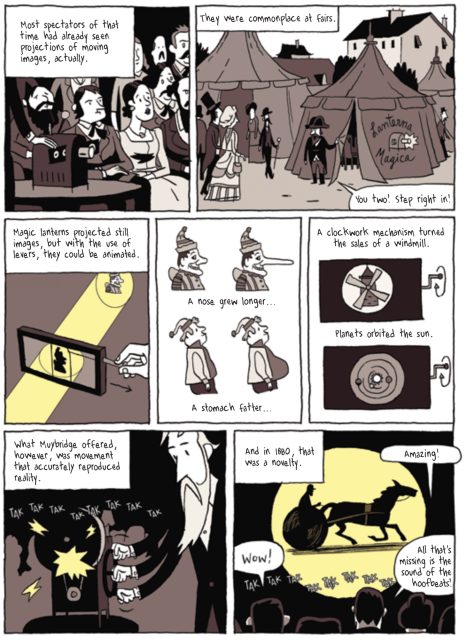

Delisle’s layout changes during the murder of his wife's lover and during Muybridge’s death, portraying each of those dramatic scenes as if they are happening in a movie, eighteen small panels per page to mimic the frames of a motion picture reel. Similarly, when Delisle shows how Muybridge was able to capture the horse’s motion using twelve different cameras, he inserts a reference to the “bullet time” sequence in The Matrix, showing how Muybridge’s work lives on in the Wachowskis’ work. Late in the biography, Delisle even breaks the fourth wall, drawing himself as he traditionally appears in his autobiographical works talking about when he first bought a book of Muybridge’s work in 1987 when he was learning about animation. Such decisions reinforce the idea of setting Muybridge’s achievements in a wider tradition of technological and artistic development.

Delisle also shows the broader context of various responses to the rise of photography, briefly pointing out how Muybridge’s developments affected the wider artistic scene of the day. He quotes Charles Baudelaire’s dismissal of photography, while also writing, “Despite his scathing criticism of the daguerreotype, Baudelaire sat for portraits by renowned photographers like Nadar and Carjat throughout his life. . . . The very portraits I used for this caricature [of Baudelaire].” “Caricature” is a good way to describe Delisle’s overall style, but, more importantly, these layers of art come up repeatedly throughout the work. During Muybridge’s attempts to capture the galloping horse, newspapers followed his progress. However, they were unable to print a photograph. Instead, they ran what Delisle describes as “an engraving of a photograph of a painting based on the original photograph,” raising the question of what art can capture. Also, just before Muybridge is able to capture the galloping horse, Delisle alludes to a group of artists who were kept out of the 1874 Paris Exposition, a group that rented space in Nadar’s (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon’s) photography studio, where “the story of those who would come to be known as the Impressionists begin,” an irony Delisle briefly comments on. Photography changes the approach to painting, a change which begins in a photographer’s studio.

Delisle also shows the broader context of various responses to the rise of photography, briefly pointing out how Muybridge’s developments affected the wider artistic scene of the day. He quotes Charles Baudelaire’s dismissal of photography, while also writing, “Despite his scathing criticism of the daguerreotype, Baudelaire sat for portraits by renowned photographers like Nadar and Carjat throughout his life. . . . The very portraits I used for this caricature [of Baudelaire].” “Caricature” is a good way to describe Delisle’s overall style, but, more importantly, these layers of art come up repeatedly throughout the work. During Muybridge’s attempts to capture the galloping horse, newspapers followed his progress. However, they were unable to print a photograph. Instead, they ran what Delisle describes as “an engraving of a photograph of a painting based on the original photograph,” raising the question of what art can capture. Also, just before Muybridge is able to capture the galloping horse, Delisle alludes to a group of artists who were kept out of the 1874 Paris Exposition, a group that rented space in Nadar’s (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon’s) photography studio, where “the story of those who would come to be known as the Impressionists begin,” an irony Delisle briefly comments on. Photography changes the approach to painting, a change which begins in a photographer’s studio.

This larger context-setting makes up much of the second half of Delisle’s biography, overall, though the first half sets it up as well. Delisle includes a good deal of information about Leland Stanford, the man who hired Muybridge to try to capture the picture of the galloping horse, as Stanford wanted both to win the debate about whether all four of a horse’s legs left the ground at the same time and to improve training practices, as he was a competitive horse owner. There’s even a hint that Stanford might have helped Muybridge during his murder trial. Stanford shows up in the second half of the book, but in a much more negative light when he doesn’t give Muybridge credit for the work he did when working with Stanford, even though Muybridge didn’t take a salary for that work.

Muybridge travels around the country giving lectures about his photography, which is when he begins to develop technology that will help lead to what people first called moving pictures. Muybridge created a projector that made it appear as if the horse were actually galloping, astounding audiences of the time, quieting skeptics of his accomplishments in what some critics referred to as the most significant cultural event of the time. Throughout this part of the book, Delisle shows Muybridge meeting with and influencing a variety of inventors, photographers, and scientists who build upon his work, whether that’s Jules-Étienne Marey, who used photography for scientific development or George Méliès, Alice Guy, and the Lumière brothers, all of whom helped developed motion pictures by building on Muybridge’s work.

Delisle goes into greater depth in describing Muybridge’s meetings with Thomas Edison, whom Delisle describes not only as a “great inventor,” but also an “unscrupulous businessman.” Rather than working with Muybridge, Edison only meets with him once, then tries to replicate his projector on his own. In fact, every time Edison meets somebody working on a projector, such as Émile Reynaud, he takes whatever knowledge he can from them, then tries to create it on his own rather than working together. Delisle’s book, then, is another piece of evidence in the long-running debate about how much credit Edison deserves for his supposed inventions, given how much he took from other people. Fittingly, there’s even a brief reference to Nikola Tesla and Edison’s attempts to discredit him, as Delisle points out that Edison essentially invented the electric chair to try to show how dangerous Tesla’s approach to electricity was.

Delisle goes into greater depth in describing Muybridge’s meetings with Thomas Edison, whom Delisle describes not only as a “great inventor,” but also an “unscrupulous businessman.” Rather than working with Muybridge, Edison only meets with him once, then tries to replicate his projector on his own. In fact, every time Edison meets somebody working on a projector, such as Émile Reynaud, he takes whatever knowledge he can from them, then tries to create it on his own rather than working together. Delisle’s book, then, is another piece of evidence in the long-running debate about how much credit Edison deserves for his supposed inventions, given how much he took from other people. Fittingly, there’s even a brief reference to Nikola Tesla and Edison’s attempts to discredit him, as Delisle points out that Edison essentially invented the electric chair to try to show how dangerous Tesla’s approach to electricity was.

Even though, late in the book and in Muybridge’s life, it appears that Muybridge is “yesterday’s news,” as he thinks of himself, Delisle’s book shows the continuing impact that Muybridge’s work has on animation, motion pictures, even graphic works including Delisle’s own. By setting Muybridge’s work in this historical context, he can show how a self-taught photographer influenced approaches to representing motion, whether in photography, on the page, or on a screen during his time and for generations to come. Delisle’s work pays homage to one who has clearly influenced him and so many others, as he wants Muybridge to get the credit he deserves.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·