Bailey Duarte as Mike Diana in The State of Florida vs. Mike Diana. All photos of the play by Zach Rabiroff.

Bailey Duarte as Mike Diana in The State of Florida vs. Mike Diana. All photos of the play by Zach Rabiroff.About midway through The State of Florida Versus Mike Diana, the new play by Lenny Schwartz that ran recently at the Daydream Theatre Company in Providence, Rhode Island, a group of the title character’s persecutors gather in a courthouse to discuss the trial ahead. Among them is the judge overseeing the case, the prosecutor for Pinellas County, Florida, and the police officer who, under an assumed name, had mounted the undercover sting that brought Diana to trial. Depending on one’s point of view, they have come either to convict an amateur pornographer, or to plot the downfall of an innocent man.

“Time to pick a jury for the Michael Diana case,” says the prosecutor. “We have to make sure we pick carefully, though.”

“Yeah,” replies the undercover detective. “We don't want to pick anyone who is going to be sympathetic to this transgressive metalhead.” The judge, for his part, just wants to make it to lunch on time.

The scene is emblematic of the tone of the play, which proceeds as a series of increasingly fraught confrontations: Mike Diana vs. his fundamentalist schoolteacher, Mike vs. the undercover investigator, Mike’s attorney vs. a hostile judge and jury whose verdict is already preordained. The implication is of less a prosecution than a persecution: the hunting and flaying of a conspicuously unassuming and innocent comic book artist. That the artist in question was the creator of a book that, even 30 years later, is capable of causing readers to involuntarily wince is left strategically and politely off stage.

For a particular generation of comic readers (albeit, perhaps, a diminishing one), Mike Diana’s name will be familiar, though not for enviable reasons. In 1994, following a four-day trial in Pinellas County, Florida, Diana became the first, and to date the only, comic artist convicted on criminal charges of obscenity. The material that prompted the conviction was Boiled Angel, an eight-issue self-published zine that by its later issues consisted of some 80 photocopied pages of unapologetically sexual, violent, and religiously blasphemous pictures and prose. The zine was never sold or distributed in shops. Diana (who had been making his photocopies for a time by surreptitiously using the photocopier at the high school where he worked as a janitor) was selling the issues via mail order from his home when he received an inquiry from a prospective customer identifying himself as Mike Flores, who included in his missive the reassurance that “I am not a cop.”

Mike Flores was a cop; moreover, his name was not Michael Flores, which was a recurring pseudonym for undercover operations in Pinellas County. Diana had ostensibly been a suspect in a recent string of local murders, but was shortly to become a test case for his southern county’s strict and stringent regulations around the sale of obscene material. In March of 1994, two years after Diana’s indictment, the jury returned a guilty verdict.

Then and since, Diana’s case became something of a cause celebre within an otherwise cloistered comics world. New outlets in and outside the industry (the Comics Journal itself, but also Mother Jones, Wired, and Playboy). In 2005, his story was adapted to stage for the first time by David Johnston under the title Busted Jesus Comix. In 2018 it was the subject of a thorough and diligent documentary, Boiled Angels: The Trial of Mike Diana. The story has, in the meantime, become a kind of lingering cautionary tale for avant-garde comics artists: a reminder that artistic expression, whatever its romantic appeal, carries a very real risk of getting you snuffed out by the powers that be.

Playwright Lenny Schwartz. Photo courtesy of Citizens Bank.

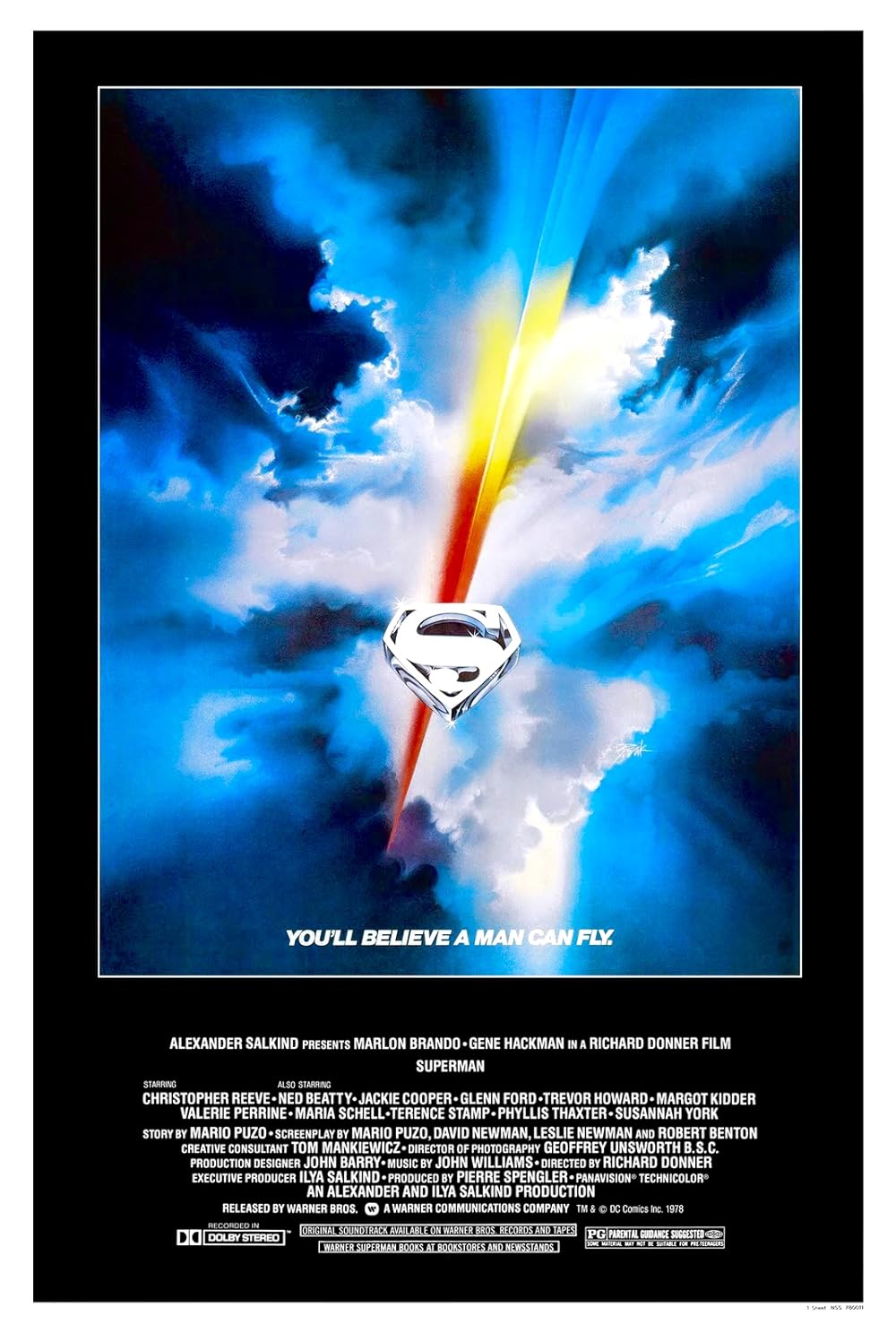

Playwright Lenny Schwartz. Photo courtesy of Citizens Bank.For Lenny Schwartz, the author of The State of Florida Versus Mike Diana, this particular moral is nothing new. Over the course of his 17 years as a playwright and screenwriter, Schwartz has written stage productions not only touching on the topic of shock and obscenity (an early play was entitled Accidental Incest) but also, separately, on some of the grimmer chapters of comic book history. His past plays have included biographical sketches of long-suffering Batman co-creator Bill Finger, and Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster (whose $300 sale of their copyright to DC Comics remains the lingering original sin of the comics business).

Schwartz comes by his interest honestly, having been a comic book reader since childhood, and a follower of Diana’s story in particular in the pages of trade journals and fan magazines at the time it happened. But where his earlier plays told stories that, for all their tragic overtones, ended with moments of reassuring triumph (Siegel and Shuster were eventually credited and given a modest stipend for their creation, as, albeit posthumously, was Finger), Diana’s saga lacks that particular reassuring cast. Though Mike Diana remains a working artist, his conviction has not, to this day, been overturned. The note of loss on which the play must end is still an unresolved dramatic thread.

It’s a thread that Schwartz has been tugging on for the past three decades. “I’ve always been interested in Mike’s story, probably since I first saw it in old issues of the Comics Journal,” Schwartz says. “I always felt like this would make a good play, but I didn’t think I had the sort of skill to write it at any point over the last 30 years. [But] I kept thinking about different things and different aspects of it, and just last year I reached out to Mike and asked, ‘Is it okay if we actually wrote something about it?’ And luckily he was wonderfully nice to say, ‘Hey, you know what, go for it.’”

Those Journal articles, along with some subsequent conversations with Diana after the latter gave his sign-off to the play, ended up providing the bulk of Schwartz’s research. He had, he says, access to a smattering of court transcripts and contemporary mainstream news reports of the trial, but, “I always find court transcripts [compared to] normal human life to be so dull. What I was trying to present, more than anything, was the heightened reality of that. So I kind of get the gist and the pull quotes from them, and give it this kind of musical rhythm.”

Geoff White as the Police Officer and Bailey Duarte

Geoff White as the Police Officer and Bailey DuarteThus, the characters in The State of Florida Versus Mike Diana tend to embody a certain surreal exaggeration compared to their real-life counterparts. In one early scene, moments after a school-age Mike has completed an art assignment by drawing the members of his family naked, his harried teacher swigs a shot of liquor at a parent-teacher conference before hustling off the stage. This can go a bit too far on the page — in scenes like the one quoted above, in which Diana’s nemeses gather to plot his downfall, the dialogue can come off uncomfortably reminiscent of the Paul Haggis film Crash, and not to its credit. But on stage, embodied by actors, it all seems to work somehow: the dialogue, in its very absurdity, takes on a black comic edge not wholly unlike that of Diana himself.

But the play’s most memorable moments really do owe themselves to absurd reality. On stage, the play’s biggest laugh comes a line taken from the court transcript when Diana was asked what he had learned from his experience: “I learned I don’t want to be in jail.”

For Schwartz, Diana’s story, ending as it does on a note of bittersweet survival albeit not victory, presents perhaps a more timely theme for the current moment. The rise, fall, and redemption of Siegel and Shuster were an optimistic story for a more optimistic age: the gritty survival of Mike Diana is a tale for the new age of Trump.

“Especially in the political environment that we’re in, my sense is that there’s nobody who can tell you not to create,” Schwartz says. “If there was a theme of the play, it was to push past that and still make your art, because whatever’s important to you matters.”

That theme, more than Diana’s art itself, became the dominating force of Schwartz’s play. In terms of genre, it is much more a traditional courtroom drama than the Künstlerroman of a budding artist – a kind of black-comedy To Kill a Mockingbird on the subject of homemade dirty books. It is conspicuous that in the 90-odd minutes of the play’s run time, the legally actionable images of Boiled Angel appear not even once.

“I thought about that,” Schwartz says. “I don’t have a problem with putting in nudity. I don’t have a problem putting in swearing. I don’t have a problem pushing the envelope, because it doesn’t scare me to do that. I actually thought about that starting out, and I said, ‘How can I get this [play] to do just what Mike did?’ And I decided that would be a disservice to the story. I think that if you’re going to do something like this, you’re going to tell a story about Mike and his case. You want it to be something classy; something that a normal person could take. … We could have easily gotten special effects [of] people getting their hearts ripped out, or had babies coming out of someone’s stomach, and really pushed things. But the person who would show up to that show would be people [already] into the genre, rather than the people who need to see it and understand why the case is important.”

So to a certain extent, Schwartz is making the calculus that Diana famously never did: tempering his outre art to the societal standards of the average theater-going Rhode Islander. Results suggest the calculation may have been a successful one — the play was a modest hit in terms of box office, and in late November was nominated for a New England Theater Award. But there remains a question of whether the production could have gotten away with pushing things further, stomach-bursting babies or not. After all this wasn’t 1991, and Providence, Rhode Island, wasn’t Pinellas County.

***

Sibyl W.eber as SB and Louis Stravato as the Judge

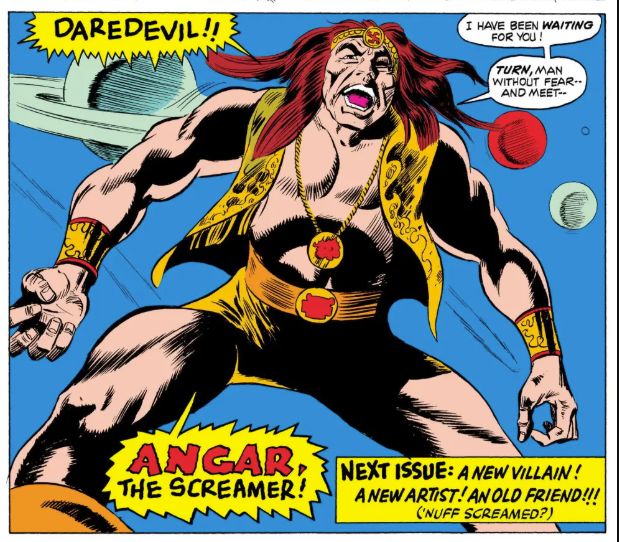

Sibyl W.eber as SB and Louis Stravato as the JudgeIn a manner of speaking, comic books have been outrunning obscenity convictions since the moment they were born. In the 1930s, mayor Fiorello La Guardia launched a wave of vice investigations into the fly-by-night pulp publishing business in New York City, prompting a number of nervous owners (among them future DC Comics founder Harry Donenfeld) to take refuge on the safer shores of child-friendly comic books.1 This was a reprieve, but only for a time: by the late 1940s, the growing preponderous of crime comics, alongside a general wave of postwar paranoia over juvenile delinquency, prompted another wave of threats, investigations, and ultimately court cases. By the early 1950s, it was the humor comic Panic, of all things, that resulted in E.C. Comics receptionist Shirley Norris being brought up on charges of “send[ing], lending, or giving away…any obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, indecent or disgusting book, magazine, pamphlet, newspaper, story paper, writing, paper, picture, drawing, photograph, figure or image, or any written or printed matter of an indecent character.” (The judge dismissed the case.)2

This overall crisis, too, was averted — in this case by means of creatiing the punishingly stringent Comics Code Authority — but that only meant that the hunt for dirty comics moved toward the outré fringes of the business. First, it was the seedy, mysterious world of erotic and pornographic fetish comics, where publishers like Leonard Burtman and Irving Klaw tried, not always successfully, to stay one step ahead of the vice squad.3 Then, in the late 1960s, it was the emerging world of underground cartooning that became the target. Among the bookstores, head shops, and independent dealers arrested for selling comics like Zap! was future direct market pioneer Phil Seuling, busted in 1973 for allegedly selling indecent material to a minor at his own monthly comic book show in New York City.4

Then, in 1986, a comic shop owner named Michael Correa was arrested while working at a shop called Friendly Frank’s in Lansing, Michigan, for selling obscene materials within range of a nearby school — the items in question being issues of Heavy Metal, Omaha the Cat Dancer, and Weirdo. The resulting trial received widespread publicity, and prompted publisher Dennis Kitchen to organize an ad-hoc group of creators to raise funds for Correa and the shop’s legal defense. This effort became the nucleus of an ongoing effort to provide legal support to figures in the comics industry facing charges of obscenity and indecency: the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.5

Thus far, all of the many cases of comics-related obscenity had fallen on the publishers and retailers of the materials (the direct censorship of artists being a much higher bar to clear under most statutes), but it was tacitly understood that it was only a matter of time before someone tried their luck. It was equally understood, at least by the CBLDF, that such a case would be likely to attract attention. And so, in 1992, Mike Diana placed a call to the Fund, and they in turn made a phone call to a Pinellas County lawyer with a sharp eye for publicity named Luke Lirot.

Lirot was an unusual figure in Pinellas County, albeit the kind of eccentric outsider who not infrequently tends to appear within the most hardline Southern communities. Like Diana himself, who had moved as a child from New York state to suburban Florida, Lirot was a quasi-outsider. Though a native Floridian, he had spent much of his life on the beaches of Southern California before moving across the country to take up his legal practice. For several years prior to Diana’s arrest, Lirot been the in-house counsel for a strip club owner named Joe Redner, who had himself been the target of prosecution by local authorities, taking cases all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Lirot was a talented lawyer, but he also had an eye for the limelight, and this as much as anything is what brought him, alongside his co-counsel on the case Scott Boardman, to the CBLDF’s attention.

The Lirot who appears in The State of Florida Versus Mike Diana cuts a reserved figure: a bespectacled, straightforward defender of the law who presents a kind of straight man against the simple-country-lawyer theatrics of the (unnamed) counsel for the prosecution. In the play, Lirot puts forward a simple argument in defense of Diana and his art. The operative case law for obscenity was the Supreme Court’s so-called Miller Test, which stipulated that a work deemed obscene, “taken as a whole,” must lack “serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”

Thus, the Lirot of the the play explains:

Mike Diana’s comic books are art. He is an artist. You may not like the art. You may not like the artist. But his work is valid. It has a point.

When the judge then asks what, exactly the point of Boiled Angel is, Lirot replies:

It is a comment on modern society. The world we live in. The people who inhabit that world.

Today, in the real world, Luke Lirot makes much the same impression as he does in the play. There is, perhaps, more gray in his hair and mustache, but he presents an otherwise surprisingly ageless figure, with the animated but straightforward mannerisms (and unusual combination of So Cal intonations and faint Florida twang) of his stage counterpart. And his recollection of the defense counsel’s strategy is much the same.

Derek Laurendeau as the Prisoner and Bailey Duarte as Mike.

Derek Laurendeau as the Prisoner and Bailey Duarte as Mike.“The component of the Miller Test that we felt would be appropriate was that it has to lack any kind of serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value,” Lirot says. “And Boiled Angel, from our perspective, wasn't just a couple of drawings. It contained a number of articles. There were a lot of contributors that had basically expressed themselves in somewhat graphic ways, but on some very, very important political and scientific issues.”

To that end, Lirot and Boardman brought in a host of experts to testify to the artistic merit of Diana’s zine, a parade of personalities that appears in Schwartz’s play as well. “They went through [the comic] page by page,” Lirot says. “We put up posters. We had them explain that while some of these images may be somewhat repugnant, some of them are very humorous, and they're all within the context of the work as a whole.”

But what was that context? What statement was Mike Diana ultimately trying to make? On this question, 30 years later, Luke Lirot still seems less sure of putting it into words.

“I think that basically the message was that there are ways to express concern with humanity that aren't always as peaceful, and American as apple pie,” he says. “There are ways to really hit you in the face and still get that message across – to even get it across with more success because you have been grabbed by the throat; you've been shown an image that's absolutely shocking, and you're not looking at or thinking about anything else other than what is depicted in that image. And I thought that that was certainly worthy of respect. And I still do.”

In a sense, Lirot and Boardman’s argument turned the Miller Test on its head. The shock Boiled Angel presented to community standards was the artistic statement; its flirtation with the forbidden made it not obscenity but rather a protected statement of art. This was a bold argument, and perhaps a brave one, but it was also doomed from the start.

Lirot remembers the play’s portrayal of a sort of kangaroo court as a true one. “That judge did everything he could [to disadvantage the defense],” Lirot says. “He would not let us knock people off the jury who were clearly not able to be fair and impartial.”

Still, Lirot says, it wasn’t a total loss. “When you look at the grand scheme of things as disappointing,” he says, “It is from a constitutional perspective, and certainly I hate to lose a case no matter what. But I think that the notoriety [and] clear misjustice that attached to his conviction has basically made him famous. People respected us in defending him, even though we lost significantly more than the state attorneys that convicted him. In fact, I think [the state prosecutors] got a lot of negative publicity from any number of sources. So it wasn't really the step up professionally that they hoped it to be. I think it really caused them some heartache in the long run.”

So, then: a legal Streisand Effect in action. A spotlight on Lirot, a spotlight on the CBLDF, a blemish on the prosecution, and a comics reading public that suddenly knows the hitherto obscure name of Mike Diana.

But who is Mike Diana, and did he want any of it at all?

***

Photo of Mike Diana by Zach Rabiroff.

Photo of Mike Diana by Zach Rabiroff.Mike Diana doesn’t immediately strike you as a threat to society. Slouching slightly in a worn Levi’s jacket, he speaks softly and unassumingly – at no point in conversation does he ever raise the level of his voice. This is how he appears in The State of Florida Versus Mike Diana, too; shyly narrating his story to the audience, he often fades into the background of the colorful characters and allegedly obscene art populating his case. He seems a cipher in the midst of personalities who wanted to be larger than life.

This is how Lirot remembers him as well, and there is an inevitable contrast between who Diana was (or appeared to be) and both the art he made, and the circles he moved in. On the latter point, Lirot says that at the time of the trial, Diana was engaged to an exotic dancer (and local public access television personality) who went by the name of Suzy Morbid. “They would be in the courtroom, and the good luck kiss was usually a French kiss of about 11 minutes,” Lirot says. “It was just a very, very intriguing aspect of this trial. And they were definitely avant-gard, cutting edge, you name it.”

“He ran with a circle of friends that were pretty eclectic,” Lirot tells me. “My recollection is that when going into court, his group of friends would have to go through the metal detector, and apparently they had portions of their anatomy with spikes and things like that that they couldn't take out in public. So it was a long time for them to get through security until they took the items away from their private parts, which I thought was fascinating.” Yet as for Diana himself: “He was very quiet, very reserved, very polite,” Lirot says.

These days Diana lives in the less prosecutorial environs of Queens, in an apartment owned by unusually absentee landlords. The building has been in the process of being sold for several years, he tells me, and the apartment above his own has been vacant during that time. So Diana has been using it as a makeshift studio for his current projects. He’s not worried about voiding his lease, though: “They don’t seem like the kind of landlords who will find out,” he says.

Diana’s goatee is gray today, and he has long since lost the full head of blonde Jeff Spicoli hair he sported during his trial, but he otherwise comes off much the same as his stage counterpart. I wondered if he and the actor who portrayed him in the Providence production, Bailey Duarte, had spoken to help Duarte prepare for the performance. Diana says that they did, but, characteristically, is quick not to take any credit for the results. “I talked to him on the phone,” Diana says. “He wanted to get an idea where my mindset was, or where I was coming from. And I think he was responsible for a good amount of that, just being right [in capturing] me and what my intentions were at the time.”

Truth be told, Diana has spent quite a lot of time thinking about the trial ever since it happened. That’s only partly because of the people – playwrights, documentarians, reporters – who keep asking him to relive it. It’s also because he knows as much as anyone how the saga of his trial and conviction has come to convey a statement as meaningful as anything else his art has had to say.

And what it had to say in the first place, Diana says, was about connection. “I could go out of my community, in a way, without leaving,” Diana says of his work on Boiled Angel. A skinny, reserved kid, an artist at heart, feeling like an outcast in a Southern and deeply Christian community, comics and zines were his bridge to a world more like his own. That — not shock, or blasphemy, or pornography — was the statement Boiled Angel was trying to make.

When the play premiered in Providence, Mike had tickets to opening night: after driving up the theater in a car filled with pizzas for the cast and crew, he watched his own life play out in front of him all over again. It was, he admits, a little intense. “I knew they were pushing 30 years [in prison],” he says, remembering his trial. “Jail time is one thing. It was three misdemeanors. Luke said that they could have prosecuted as felonies — he doesn't know why they didn't. It was madness. I mean, I was always nervous all the time.”

Like Lirot, he remembers his chances of succeeding with the jury being slim from the start. At one point, he remembers, the prosecutor had images from one of Diana’s comics blown up for the jury to inspect. “He started to describe it, and he said something like, ‘I like the way he drew this part here,’” Diana says. “I couldn't help it. I was not expecting him to say that, or whatever. And I kind of laughed for a second, and my lawyer looked at me and I went, ‘Oops.’ And my lawyer later told me that one of the jury members looked over at me right when I chuckled, which might've been a big mistake. Maybe that cost me the whole case.”

Others I had spoken to had suggested that many of the players involved in the case — the prosecutors, the CBLDF, Lirot himself — had kept at least one eye on the publicity that would come out of the case, and when I suggested to Diana that he didn’t strike me as someone particularly eager for the spotlight, he laughed.

“Of course not,” he says. “I mean, I was keeping this a secret on purpose. I knew everyone in my community was a jerk and that it was a very religious community. … That [being exposed] was my worst fear, in a way. I had stage fright. And going to court, having to defend yourself, that's the worst [outcome] of that. And having my artwork, which I consider just my private drawings … if I knew people were going to be reviewing it that way, I probably never would've drawn it. And that's troubling in itself, too: how people censor themselves thinking about what others might think. That'd be like you don't write truths in your diary because someone might read it someday.”

The cast from top left clockwise: Derek Laurendeau, Sibyl Weber, Louis Stravato, Geoff White, Lionel LaFleur, Stephanie Sivalingam, Dennise M. Kowalczyk, Bailey Arruda, Bailey Duarte, Jamie Lyn Bagley, Jeannette Lake, Gayle Furman, Padriag Mahoney, and Bailey Goff.

The cast from top left clockwise: Derek Laurendeau, Sibyl Weber, Louis Stravato, Geoff White, Lionel LaFleur, Stephanie Sivalingam, Dennise M. Kowalczyk, Bailey Arruda, Bailey Duarte, Jamie Lyn Bagley, Jeannette Lake, Gayle Furman, Padriag Mahoney, and Bailey Goff.You might think, then, that watching The State of Florida Versus Mike Diana would be a whole different sort of trial for its titular figure. It is, after all, an extended and personal confession of his art in literary form; a public diary-reading of sorts. But Diana seems enthusiastic about what he saw on stage, and about the work Schwartz and the cast did to capture his story. He was impressed with the play’s accuracy, though he does note a few of smaller deviations from the historical record (at one point in the play, officers of the court ask the Diana to remove any jewelry before he’s sent to jail, and he hands over a necklace he’s wearing; in real life, Diana says, he had come to court that day jewelry-free).

Indeed, the play may have inspired Diana to finally take the leap in telling his story himself. “Actually, ever since the trial, I always wanted to do my autobiography,” Diana says. “For a long time I felt like it was so close to the trial that I didn't even really want to think about it too much. But now it's been enough time where I can tell it in my own words. Like a comic, maybe trying to capture the original style [of Boiled Angel]. But I know I can do it.”

In the meantime, Diana always has new projects to work on. He’s doing a new comic called Slug with fellow artist Ryan Vella, and he’ll be re-releasing some vintage ‘90’ movies that he filmed on a VHS camcorder, this time available on blu-ray through his website. And, he says, he did get a few sales off of Schwartz’s play.

“I brought some zines [to the theater],” he says. “Some people bought some. It was good.”

Maybe Mike Diana got his payoff from all the publicity after all.

The post Playing Dirty: <i>The State of Florida Versus Mike Diana,</i> a new drama about a notorious comic book obscenity case appeared first on The Comics Journal.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·