Sean McCarthy | September 10, 2025

In 2025, when most Americans seem to get their news from TikTok, newsprint may carry a whiff of nostalgia. Smoke Signal publisher/editor Gabe Fowler knowingly courts this charge with a series title referring to an even earlier, premodern form of ephemeral communication. Gary Panter is a dyed-in-the-wool postmodernist, and postmodernists have been accused of nostalgia for decades, at least since a split pediment appeared on top of 550 Madison Ave in 1982 — the year the Jimbo Raw One-Shot came out. I prefer to think of postmodernism’s engagement with the past the way Frederic Jameson did, as “an attempt to think historically in an age that has forgotten how to think historically in the first place”. Smoke Signal #44 — like its predecessors, an 11” x 17” tabloid newspaper printed on crisp, bright newsprint which creates a satisfying crackle every time a page is turned — allows us to watch Panter think historically and visually as he meditates on cartooning as writing, drawing, and illustration, as well as its relationship to 19th-century broadsheets and 20th-century funny pages.

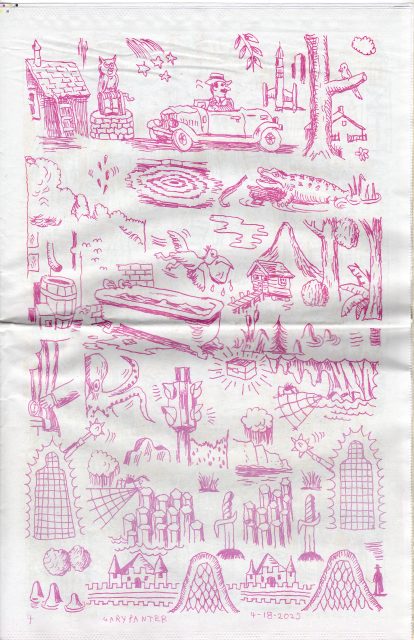

Smoke Signal is Brooklyn comics shop Desert Island’s in-house newspaper, free for visitors to the shop while supplies last (everyone else pays $10), a gift from Fowler to his patrons and a source of consistently high-quality comics and related artwork for 16 years and counting. Panter’s first contribution to the series was a drawing for the cover of issue #15 in 2013; twelve years and a few more appearances in its pages later, Smoke Signal #44 is entirely Panter’s own, a one-man dispatch subtitled Flycatcher. Its format invites comparisons to Fog Window, a newspaper Panter made as part of a broader project to recover a practicable utopianism from hippie culture without the seedy underbelly (a project that also included his last comic book, Crashpad). But Flycatcher achieves a kind of timelessness by casting a wider, deeper net. It’s a drawing monograph by a master draftsman disguised as a comics newspaper. Every drawing is signed and dated individually, something Panter does even in his graphic novels to remind the reader that each page is a work of art, both whole in itself as well as part of a larger whole . The drawings here are from a five-week period, 4/16–5/20/25; after layout, printing, and shipping, I was holding it in my hands on Aug. 1.

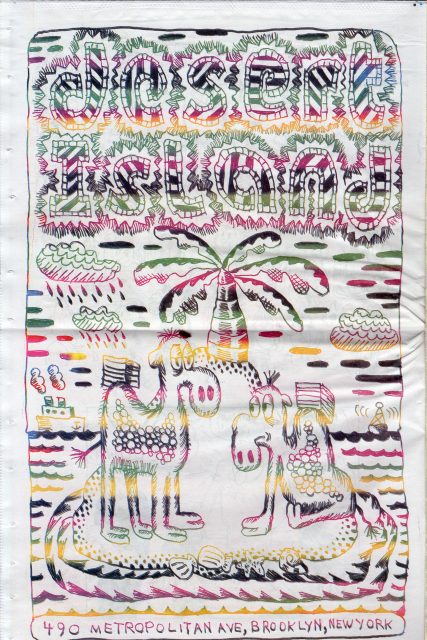

The rainbow-roll-printed cover features Astro Boy, but Mighty Atom (as he’s known in Japan) may be the more appropriate name here. He’s drawn as an agglomeration of particles and waves, a kind of avatar for the act of creation outlined in the prelude to Crashpad, which proclaimed “Art tries to grasp and pass on the cosmic order." Exuberant shapes play across his likeness: triangles that create figure-ground reversals in his hair, spheres in his brain like literal marbles, dots and lines growing and hatching across his face and exerting pressure on the legibility of the iconic image, increasing the degree of abstraction contained in all cartoons. Sparks of energy radiate out toward shapes like amoebas designed by the Memphis Group to evoke elemental building blocks of life and art. The back cover features a redrawing of John Broadley’s Desert Island logo, but the camels look distinctly nonplussed as circular growths fill their bodies and rainclouds gather above the horizon, hinting at some of the darkness contained within.

The rainbow-roll-printed cover features Astro Boy, but Mighty Atom (as he’s known in Japan) may be the more appropriate name here. He’s drawn as an agglomeration of particles and waves, a kind of avatar for the act of creation outlined in the prelude to Crashpad, which proclaimed “Art tries to grasp and pass on the cosmic order." Exuberant shapes play across his likeness: triangles that create figure-ground reversals in his hair, spheres in his brain like literal marbles, dots and lines growing and hatching across his face and exerting pressure on the legibility of the iconic image, increasing the degree of abstraction contained in all cartoons. Sparks of energy radiate out toward shapes like amoebas designed by the Memphis Group to evoke elemental building blocks of life and art. The back cover features a redrawing of John Broadley’s Desert Island logo, but the camels look distinctly nonplussed as circular growths fill their bodies and rainclouds gather above the horizon, hinting at some of the darkness contained within.

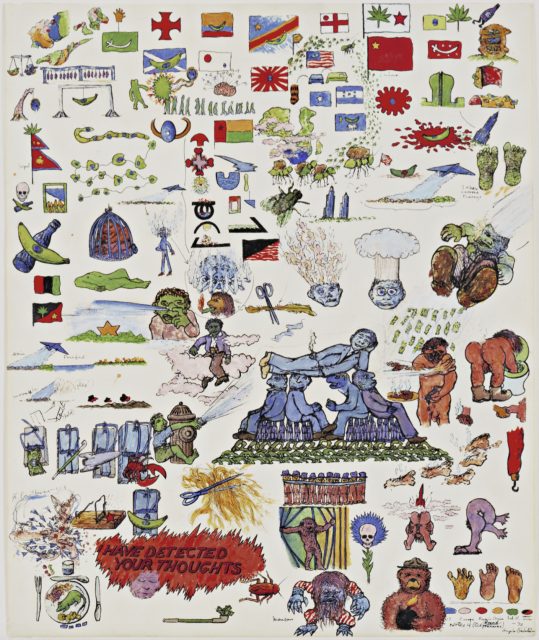

Öyvind Fahlström, Notes 4 (C. I. A. Brand Bananas), 1970. Synthetic polymer paint and ink on paper. Collection MoMA, New York.

Öyvind Fahlström, Notes 4 (C. I. A. Brand Bananas), 1970. Synthetic polymer paint and ink on paper. Collection MoMA, New York.Most of the drawings inside— printed in one color per page — are made of discrete pieces of imagery arranged in lines and grids, inevitably suggesting hieroglyphs. Öyvind Fahlström’s Notes series seem to be a significant precedent, and I also think of Philip Guston and his small paintings on masonite from the late sixties (once exhibited as A New Alphabet) that make up a kind of glossary of objects featured in his paintings of the next decade. Here Panter deploys cartoon images as building blocks in rows that function like sentences or paragraphs, whose explicit meaning is elusive. Donald Barthelme, a favorite writer of Panter’s, once said about a Rauschenberg combine, “What is magical about the object is that it at once invites and resists interpretation”. Flycatcher is a similarly magical object. The heart of all of Panter’s work is an open, associative, allusive web of images and words — this is true even of the graphic novels whose narratives are largely resolved picaresques. Panter’s eye, brain and hand form an open circuit that takes in American pop culture detritus, modern art, classic literature, underground music, etc., and creates agglomerations of pictures that traverse a space between semiology and spiritualism, where cartoons seem to exist as both semiotic signs and mystical sigils, spanning illustration and illumination.

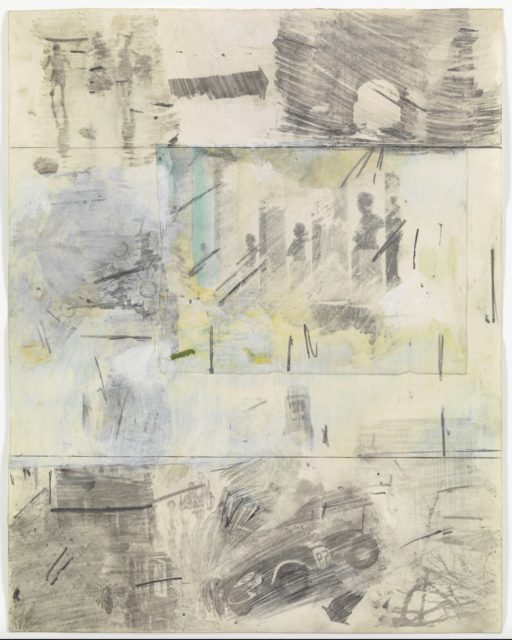

Robert Rauschenberg, Canto IV: Limbo, Circle One, The Virtuous Pagans from the series Thirty-Four Illustrations for Dante's Inferno, 1958. Solvent transfer drawing, cut-and-pasted paper, pencil, gouache, and watercolor on paper. Collection MoMA, New York.

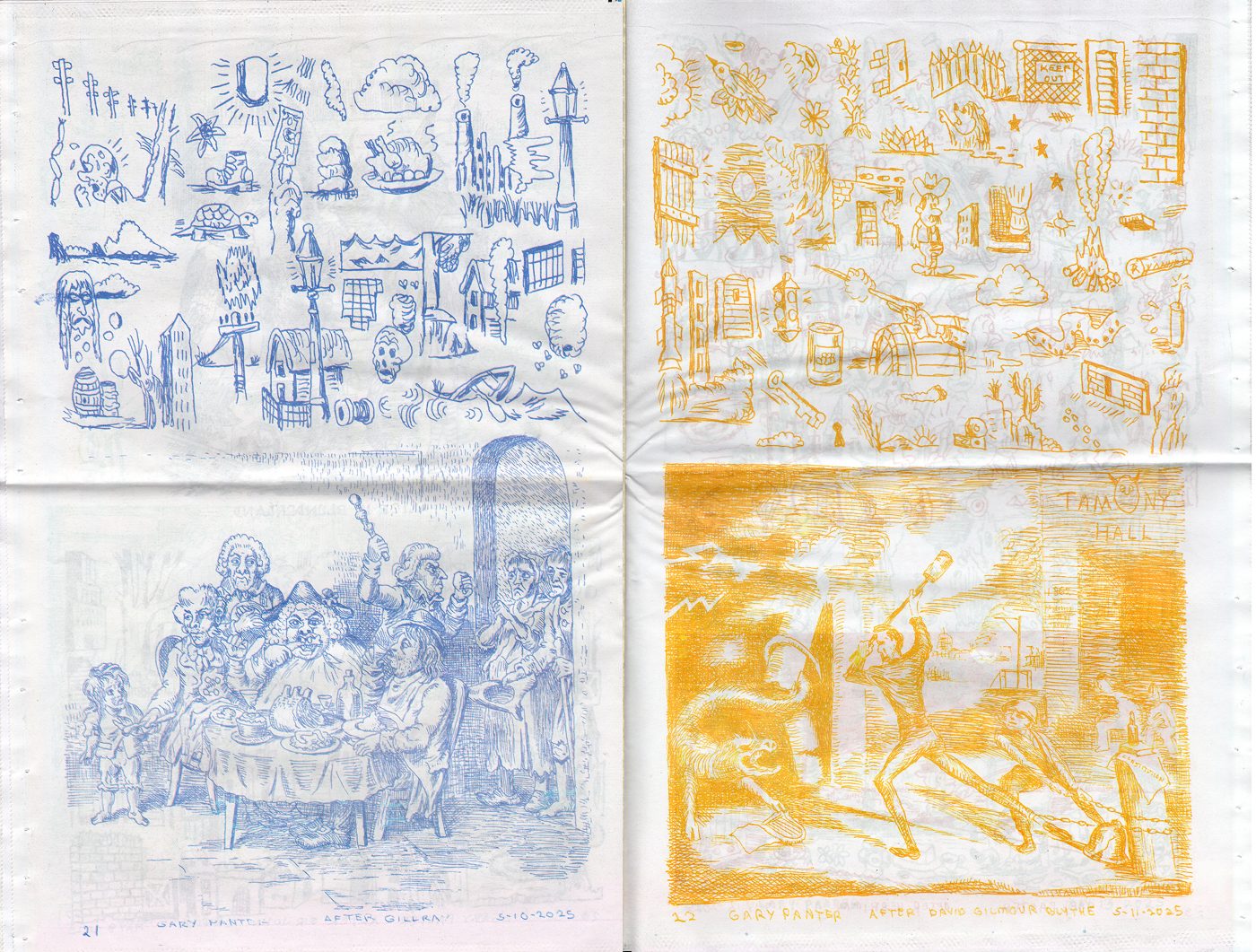

Robert Rauschenberg, Canto IV: Limbo, Circle One, The Virtuous Pagans from the series Thirty-Four Illustrations for Dante's Inferno, 1958. Solvent transfer drawing, cut-and-pasted paper, pencil, gouache, and watercolor on paper. Collection MoMA, New York.The signs and sigils that fill most of the 32 pages of Flycatcher include machines, buildings, mountains, clouds, prison yards, animals, robots, cartoon characters (Woody Woodpecker, Chilly Willy, the Jeep, Charlie Brown ), vehicles (cars, spaceships, the Batmobile), food, disembodied hands holding bags of money or pressing buttons or painting lines, and sinister grids like the ones that follow Satan around in Songy of Paradise. They are drawn in ragged, unfussy lines close to those of handwriting. Some of the drawing fragments have the absolute minimum representational information necessary to read, like a handful of short vertical marks above a longer horizontal mark for rain, for instance. Tiny amounts of linear perspective are contained in little blocks—almost as soon as you enter, you exit back into the void again. Negative space is hugely important and carefully calibrated; a street light flashes toward an octopus, but across an interval disrupting space and time like a gutter in a more conventional comic. Space and time are disrupted at a larger scale in these drawings as well, as Panter invites us to try to read something like an ancient hieroglyphic text — say, the Egyptian Book of the Dead — made up of images of our own relatively recent pop culture past.

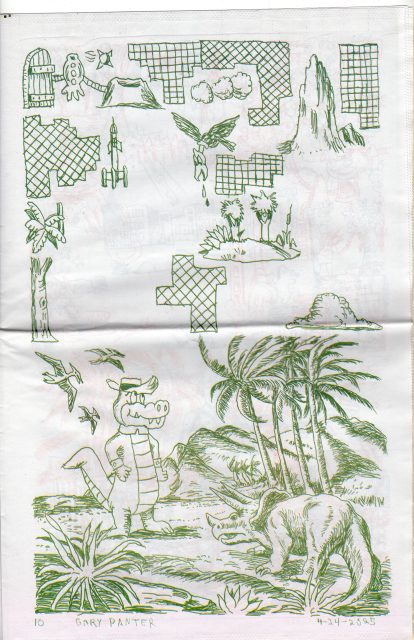

About a third of the way through Flycatcher the drawings begin to split into two around the fold across the middle of each page, with loosely defined rectangles stacked one over the other like in a Rothko painting. Here space and image start to cohere into a series of tableaus, the first featuring Wally Gator in the Crateceous facing off with a triceratops while a trio of pterosaurs glide on the breeze. A few pages later some of the hieroglyphic layouts also start to cohere thematically. One features icons of the desert (mountains, cacti, vultures, skulls, desperate dudes crawling toward a mirage of a cooked turkey); in another, cowboys fire guns indiscriminately into fragments of frontier landscape, giving way to more dinosaurs below.

Flycatcher also contains several more or less faithful renditions, in Panter’s imitable hand, of pictures by other artists, including several sociopolitical satires of the 19th century, such as Thomas Nast’s drawing of Boss Tweed as a defeated emperor from 1871; Cruikshank’s “Tremendous Sacrifice” from 1847, featuring seamstresses fed into a giant sausage grinder which turns them into clothes and money; a James Gillray drawing of a gluttonous upper-crust family feasting while their servants beat beggars away from the door; and “Lincoln Crushing the Dragon of Rebellion,” an oil painting by David Gilmour Blythe, sending up Tammany leader Fernando Wood’s bad faith attempts to hamstring Lincoln’s fight against the Confederacy. Even the Tenniel drawing of Alice in Blunderland comes not from one of Carroll’s books but from a satirical article in an 1880 issue of Punch. While the most recent of these is almost 150 years old, their timelessness (or timeliness) will be obvious to anyone appalled by contemporary American kakistocracy, oligarchy, and corruption.

The remainder of these renditions are of panels by master cartoonists of the previous century, including Herriman, Segar, and Dirks. In context even these have a somewhat sinister cast — including the panel from Krazy Kat, whose lovely, quiet nocturnal scene features, at a closer glance, some worms escaping a cycle of death as bait for fisherman Offisa Pup, while Ignatz sits behind bars in the Coconino County jail.

Other tableaus — all of which float above or below additional evocative arrangements of cartoon fragments — are pastiches of more or less familiar characters in more or less identifiable scenes, combined to unsettling effect: Gigan sweats as he’s led into a nicely appointed living room reminiscent of the one in Richard Hamilton’s Just What is it that Makes Today’s Homes so Different, so Appealing? by a bucktoothed Beaky Buzzard, while Porky Pig walks on the ceiling (putting me in mind of the Prussian Archangel from the 1920 Berlin Dada Fair); Foghorn Leghorn is a Trojan Horse dragged by several Eeyores — seemingly commanded by a squad of Droopy Dogs — toward a citadel filled with Borises from Bullwinkle. An armadillo tank fires on a platoon of clockwork mice; elsewhere a bucolic scene is overrun by creatures and characters in a cacophony reminiscent of Bruegel’s Netherlandish Proverbs. Exuberant irrationality runs through all these pictures, generating humor and horror in roughly equal measure.

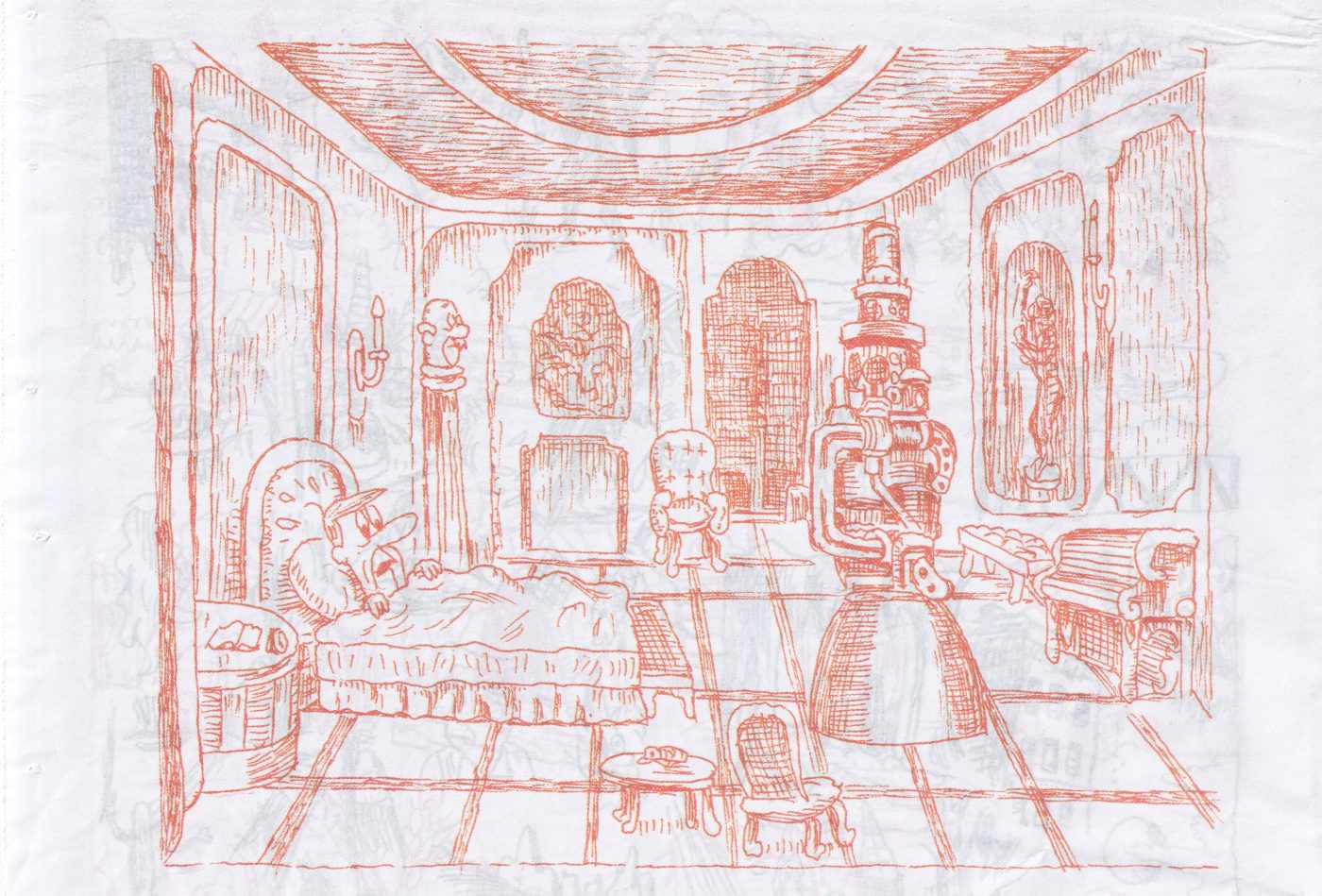

In addition to political corruption and war, mortality seems to be another preoccupation: Flycatcher features Panter’s version of Bosch’s Death and the Miser: Yogi Bear, fearsome and unkempt, with his “pic-a-nic" basket under his arm and an ominous dragonfly on his belly, takes the position of Death entering from the left. Ranger Smith, at right and wielding bear spray, takes the place of the angel; the miser, in bed in the center, is perhaps already a corpse, stinking and drawing flies while his riches — records and toys, mostly — are strewn around the floor of his crumbling home. (Is that Officer Dibble lying there dead on the floor as well?) Meanwhile, George Jetson (family man and personification of mid-century techno-optimism) is also lying in bed in the uncanny rococo room from the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey, past the psychedelic light show of “Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite”. In place of the monolith — itself an image of mortality, the awareness of which it brings to the apes and jumpstarts their evolution to the terrifying tune of Ligeti’s Requiem — is a robot I couldn’t identify, perhaps Rosie as a kind of Dalek or a sculpture by Eduardo Paolozzi. Otherwise isolated from his family, George, like astronaut Dave Bowman in the film, is at the end of his life, but also the beginning of his rebirth.

In addition to political corruption and war, mortality seems to be another preoccupation: Flycatcher features Panter’s version of Bosch’s Death and the Miser: Yogi Bear, fearsome and unkempt, with his “pic-a-nic" basket under his arm and an ominous dragonfly on his belly, takes the position of Death entering from the left. Ranger Smith, at right and wielding bear spray, takes the place of the angel; the miser, in bed in the center, is perhaps already a corpse, stinking and drawing flies while his riches — records and toys, mostly — are strewn around the floor of his crumbling home. (Is that Officer Dibble lying there dead on the floor as well?) Meanwhile, George Jetson (family man and personification of mid-century techno-optimism) is also lying in bed in the uncanny rococo room from the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey, past the psychedelic light show of “Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite”. In place of the monolith — itself an image of mortality, the awareness of which it brings to the apes and jumpstarts their evolution to the terrifying tune of Ligeti’s Requiem — is a robot I couldn’t identify, perhaps Rosie as a kind of Dalek or a sculpture by Eduardo Paolozzi. Otherwise isolated from his family, George, like astronaut Dave Bowman in the film, is at the end of his life, but also the beginning of his rebirth.

The tone of Flycatcher is is alternately playful and melancholy, fun and elegiac; all of it is drawn with the love, joy, and enthusiasm Panter brings to all his work. At the end of this enchantingly troubling meditation on cartooning and meaning, Alice the Goon exclaims in panicky, indecipherable scribbles while the Sea Hag yells “AW PIPE DOWN!” Perhaps now I’m suffering from a kind of paranoia induced by semiotic overload, but from here my synapses fire from PIPE DOWN to Popeye’s pipe to Magritte’s (not a) pipe, which of course appears in an artwork entitled The Treachery of Images.

Paranoid or not, these are connections made in the brain of a living reader experiencing a physical object containing work made by one of our greatest living artists. Flycatcher is a product of a lifetime of looking, reading, thinking, feeling, and drawing. Panter was once a child entranced by cheap comic books carried at his father’s five-and-dime store; he once told Tom Spurgeon that his paintings all begin with the question “Where’s the water,” an urgent concern of all biological life. It's a question much on the minds of our would-be overlords in Silicon Valley too, who need staggering amounts water for their AI centers to realize a sad, empty dream of art without artists. While they're leveraging what they can steal from our collective cultural past and our ecological future — betting the house on a population too indifferent or distracted to care about the difference between art made by a human and probabilistically determined images made by a machine — Gary Panter takes a long view and shows us the difference again and again, line by ratty line.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·