The term “replacement theory,” a designation for a Right-leaning conspiracy theory, didn’t come into vogue until French author Renaud Camus coined the term in 2011. In that context, Camus argued that vested interests in Europe were attempting to replace White Europeans with immigrants, legal or otherwise, the better to control the population. Camus made the interesting remark, derived from Brecht, that “the easiest thing to do for a government that had lost the confidence of its people would be to choose new people.”

In September 2025 I argued that many of the political disagreements in American society stemmed from a conflict between two ethical systems: the Ethos of Keeping and the Ethos of Sharing. In that three-part essay-series, I concentrated on explicating the idea first and then provided particular examples of the idea’s application in pop culture. This time, I’ll go the other way and start with an example.

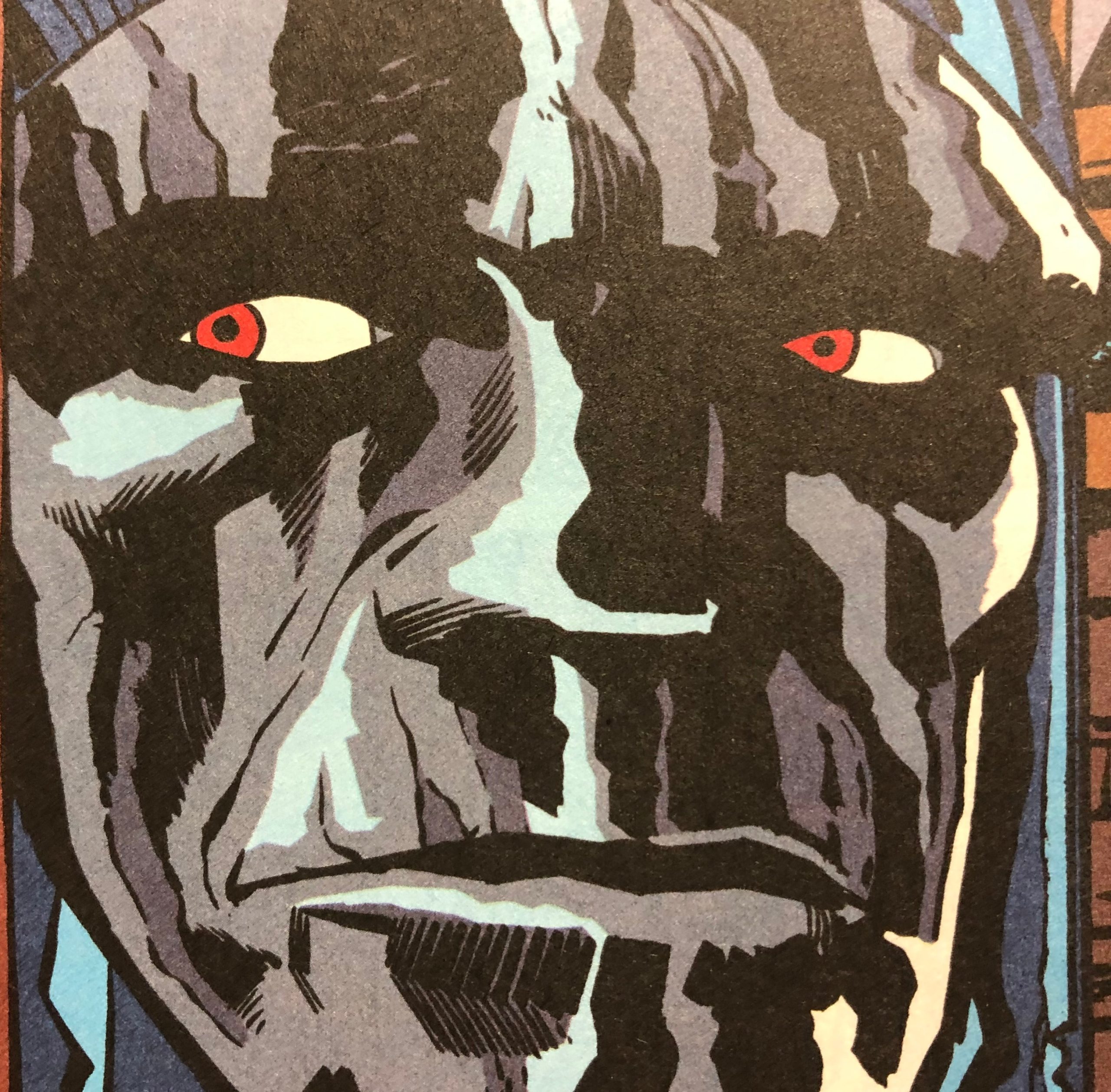

Since I won’t address “replacement theory” in terms of immigration law and politics until Part 2, here I’ll concern myself with “the superhero replacement theory” that arose at Marvel Comics in the 2010s. This was a loose editorial policy aimed at portraying the Marvel Universe as having been too dominated by the Dreaded White Male, a tendency that the new breed of editors, like Axel Alonso, proposed to correct. TIME thought it worth covering this replacement of old characters with new ones, supposedly more diverse in terms of race, ethnicity and gender– and all this roughly a year before the Marvel Cinematic Universe became heavily invested in its own replacement theory.

Alonso, a journalist turned modern-day mythologist, is leading the world’s top comics publisher during a time of great disruption. In an industry historically dominated by caucasian males, Alonso is breaking the laminated seal of stodgy tradition by adding people of every ilk to the brand’s roster of writers and dramatis personae. Under his watch, the Marvel universe has expanded to accommodate costumed crimefighters of myriad ethnicities: a biracial Spider-Man, a black Captain America, a Mexican-American Ghost Rider, to name a few.– “Meet the Myth-Master Reinventing Marvel Comics,” 2017.

It’s ironic, though, that the TIME essay appeared in 2017, for by that time, the most famous/infamous replacement– that of White Captain America by Black Captain America– had utterly failed. According to the first collection of SAM WILSON CAPTAIN AMERICA, there were about a dozen stories in which Sam Wilson, formerly “The Falcon,” assumed the mantle of star-spangled avenger. Following those dozen appearances, Marvel launched CAPTAIN AMERICA: SAM WILSON. This title lasted 24 issues from 2015 to 2017, with all scripts written by Nick Spencer. Spenser made his biggest splash with the notorious “Secret Empire” plotline, in which White Captain America was revealed to be an agent of Marvel’s Nazi-adjacent terrorist cabal. Hydra. But I only read the first six issues of Spenser’s WILSON, which just happen, in a serendipitous manner from my POV, to concern illegal immigration.

Spenser doesn’t bestow individual titles on any stories in the six-issue arc. So because Wilson-Cap’s main opponents are the Sons of the Serpent and the Serpent Society, I’ll give the arc the arbitrary Marvel-style title “Serpents in Eden,” albeit with the caveat that my ideas of who the serpents really are isn’t the same as Spenser’s. I’ll pay Spenser a small compliment: while “Serpents” is a one-sided Liberal take on immigration, it’s not nearly as stupid as either of the MCU stories focused on Wilson-Cap: 2021’s teleseries FALCON AND THE WINTER SOLDIER and 2025’s CAPTAIN AMERICA: BRAVE NEW WORLD. But Spenser is unapologetic about slanting his discourse on America’s unsecured borders by relying on that hoary old Liberal cliche. the “Honest Juan” paradigm.

So, Wilson-Cap is approached by the grandmother of one Joaquin Torres about her missing grandson. I think Spenser meant to imply that both Joaquin and his grandma were US citizens, though the writer doesn’t actually say so. But Joaquin does resemble just about every other illegal-lover in American pop culture. Joaquin sets up resources to help migrants survive their attempts to illegally cross the border– which proves he’s a good guy, because he’s saving lives but not directly providing aid in said crossings. (The grandma is careful to say that Joaquin is not a coyote.) Wilson-Cap soon discovers that a new incarnation of the Sons of the Serpent– originally an American-nationalism group introduced in the 1960s– has been kidnapping migrants to use for the subjects of mutation experiments.

However, these Sons are only hired thugs, working for the Serpent Society, rebranded as “Serpent Solutions.” The new snake-fiends are oriented upon getting rich White conservatives to invest in their villainous schemes– because, as we all know, there are no Liberals who ever promote massive illegal schemes. In the midst of all this politically tinged superhero actions, not much is said about most of the migrants victimized– except Good Samaritan Joaquin. As it happens, when he gets mutated, he gets turned into a guy with natural arm-wings, so that by the climax of “Serpents,” Joaquin gives up helping illegals and assumes Wilson-Cap’s old ID of “The Falcon.” Not that Wilson-Cap ever totally dropped the avian part of his identity. I think two crusaders with wings, but not with a mutual bird-motif, feels a lot like gilding the lily, but that’s me.

There are certainly some entertaining bits in “Serpents.” Wilson-Cap has a “will they-won’t they” thing going in these six issues with old femme-favorite Misty Knight, and for a good portion of the story the hero gets transformed into a wolf-man, which is a callback to a nineties CAPTAIN AMERICA arc, “Man and Wolf.” But naturally Spenser’s political take on illegal immigration is completely dishonest. He puts into the mouth of the villains’ leader the standard claim that objections to illegals is all about xenophobia: “Afraid of losing your job? Perhaps you’d be interested in a border wall to keep out immigrants who might undercut your current pay.” The presumption here is that average Americans ought to be willing to let their wages be cut by greedy corporations– the same ones Spenser excoriates– because the presence of cheap scab labor makes such wage-cutting feasible. As with most Leftist racial theories, the persons thought to be “marginalized” are incapable of causing harm, even unintentionally. They can only be framed as victims, even if real-world victimage doesn’t involve getting turned into human-animal hybrids.

As an ironic conclusion to this particular part of Marvel’s replacement experiment, after the final issue of SAM WILSON CAPTAIN AMERICA in 2017, another group of raconteurs came out with an eight-issue FALCON series running from 2017 to 2018, possibly in an attempt to please the readers who wanted Sam Wilson to return to his previous super-ID. However, Axel Alonso was only credited as Marvel’s editor-in-chief for the first three episodes of this series, and by issue four he had been ousted from the position by his successor C.B. Cebulski, whose editorial credit appears on the remaining five issues. I didn’t read this series any more than I read the rest of the Spenser issues of WILSON, so I don’t know what rationale was used to restore the status quo. But clearly the failure of Wilson-Cap indicates that the Marvel readership wanted to “Keep” Steve Rogers as their Captain America and didn’t support the commandment that they ought to “Share” their entertainment with Liberals seeking to rewrite superheroes to be one-dimensional expressions of political correctness.

Next up: more stuff about “Sharing” when it takes the form of shoving messages down the mouths of consumers.

***

English (US) ·

English (US) ·