Richard Pound | February 3, 2026

It’s probably fair to say that Milt Gross has always been something of a cartoonist’s cartoonist. His spontaneous, expressive line, frenetic sense of humor, and distinctive use of Yiddish-English dialect have made him a firm favorite of artists like Ivan Brunetti, Mark Newgarden, and R. Crumb, all of whom have a deep-rooted interest in the history of the medium. There’s something electric about his work which, even at a century’s distance, remains at once uniquely of its moment and utterly timeless. Despite being a quintessential product of the Jazz Age, it didn’t seem out of place in the fourth issue of Art Spiegelman’s avowedly modernist anthology RAW, where it held its own alongside young upstarts, including Charles Burns, Gary Panter, and Bruno Richard. And yet, despite being a fixture in major surveys of American newspaper comics since the seminal Smithsonian Collection in 1977, Gross has never been honored with the kind of multi-volume reprint series lavished on his more famous contemporaries like George Herriman, E.C. Segar, or Harold Gray.

It hasn’t helped that his best-known Sunday strips, Nize Baby, Count Screwloose, and Dave’s Delicatessen, were all short-lived, none lasting longer than four years, so they never had a chance to achieve the enduring, monumental stature of Krazy Kat, Thimble Theatre, or Little Orphan Annie. But it might also be because his sprawling oeuvre is not easy to quantify, let alone anthologize, encompassing not only newspaper strips but magazine cartoons, illustrated prose, wordless novels, and comic books (not to mention short stories, radio shows, animation, and even a brief stint as a Hollywood gag writer for Charlie Chaplin). There’s always been a sense that Gross’ body of work spreads over too broad a field to be summed up in any single volume, or even format.

Various publishers have cherry-picked his career over the past two decades, with new collections of his work popping up every few years. Fantagraphics reissued his 1930 wordless masterpiece He Done Her Wrong in 2005, Yoe Books followed up with The Complete Milt Gross Comic Books and Life Story in 2009, while New York University Press published a collection of his illustrated books, Is Diss a System?, in 2010. IDW resurrected the ultra-rare Milt Gross’ New York in 2015, and finally, in 2020, Peter Maresca’s Sunday Press compiled Gross Exaggerations, a monumental collection of his best newspaper strips that, for a while, seemed like it might be the last word on all things Gross.

And yet, while each of these has added a new piece to the jigsaw, the big picture has remained frustratingly incomplete. Which is precisely why this fascinating book comes as such a welcome surprise. The first of a multi-volume series dedicated to unearthing Gross’s "lost work," it’s an impeccably researched and well-presented collection, bringing together every strip he produced for the weekly satirical magazine Judge between 1923 and ‘24. As the subtitle Mastering Cartoon Pantomime suggests, these (mostly) wordless strips show Gross perfecting the skills which he would bring to bear on his mature work, especially He Done Her Wrong, just a few years later.

The book’s author, Paul Tumey, will be familiar to anyone with more than a passing interest in early American comic strips, having contributed essays to several collections from Sunday Press (including Gross Exaggerations) and also edited essential collections of Harry J. Tuthill’s The Bungle Family and the work of Rube Goldberg. Meanwhile, his magnum opus, Screwball! The Cartoonists Who Made the Funnies Funny (IDW, 2019) is probably the definitive account of the delightfully loopy and unrestrained style of verbal-visual humor that permeated the medium in the early 20th century.

As would be expected given such a CV, Tumey has spent a lot of time looking at Gross, and brings his expertise to bear on this project with close readings of the individual strips and illuminating insights into the artist’s working methods. Whether offering a detailed analysis of Gross’ page breakdowns or scrutinizing his unconventional mark-making techniques, his writing is expert without being overly academic, and colored by a wry sense of humor that suits the subject matter perfectly. More importantly, while obviously a Gross partisan, he brings a critical eye to the material and isn’t afraid to point out when a particular strip doesn’t work.

And it’s true that not everything here ranks alongside Gross’ best work. The pacing in certain strips can seem a little bit off, and some of the punchlines don’t quite live up to their promise, while the cramped layouts and tightly drawn figures (well, tight for Gross) are a long way from the boisterous, scrawled line of his more famous work. But that’s all part of the pleasure in a collection like this. Less of a "Greatest Hits" and more of an "Early Work and Demos" type of deal, it offers an invaluable opportunity to observe an artist gradually finding his feet. As a means of developing his craft, this period was clearly important for Gross, and Tumey highlights the many instances in which he reused the routines he worked up for Judge in his later strips, sometimes almost verbatim, but elsewhere judiciously edited or tweaked to make the gags land more effectively. We can literally see him learning as he goes.

Much of the work here is a direct response to the popularity of the British cartoonist H.M. Bateman, whose shadow looms large over the entire volume. His impeccably drawn, wildly exaggerated pantomime strips in Punch and The Tatler had brought him international fame during the 1910s, and in 1923 he had been hired by Life magazine to produce a series of strips specifically for the American market. It seems to be their success that inspired Judge to follow suit, encouraging its regular contributors (including Gardner Rea, Gluyas Williams, and Percy Crosby) to directly imitate his style. This happened to be the exact moment when Gross began working for the magazine (while also holding down a full-time job as a staff cartoonist on the New York World), so he went along for the ride.

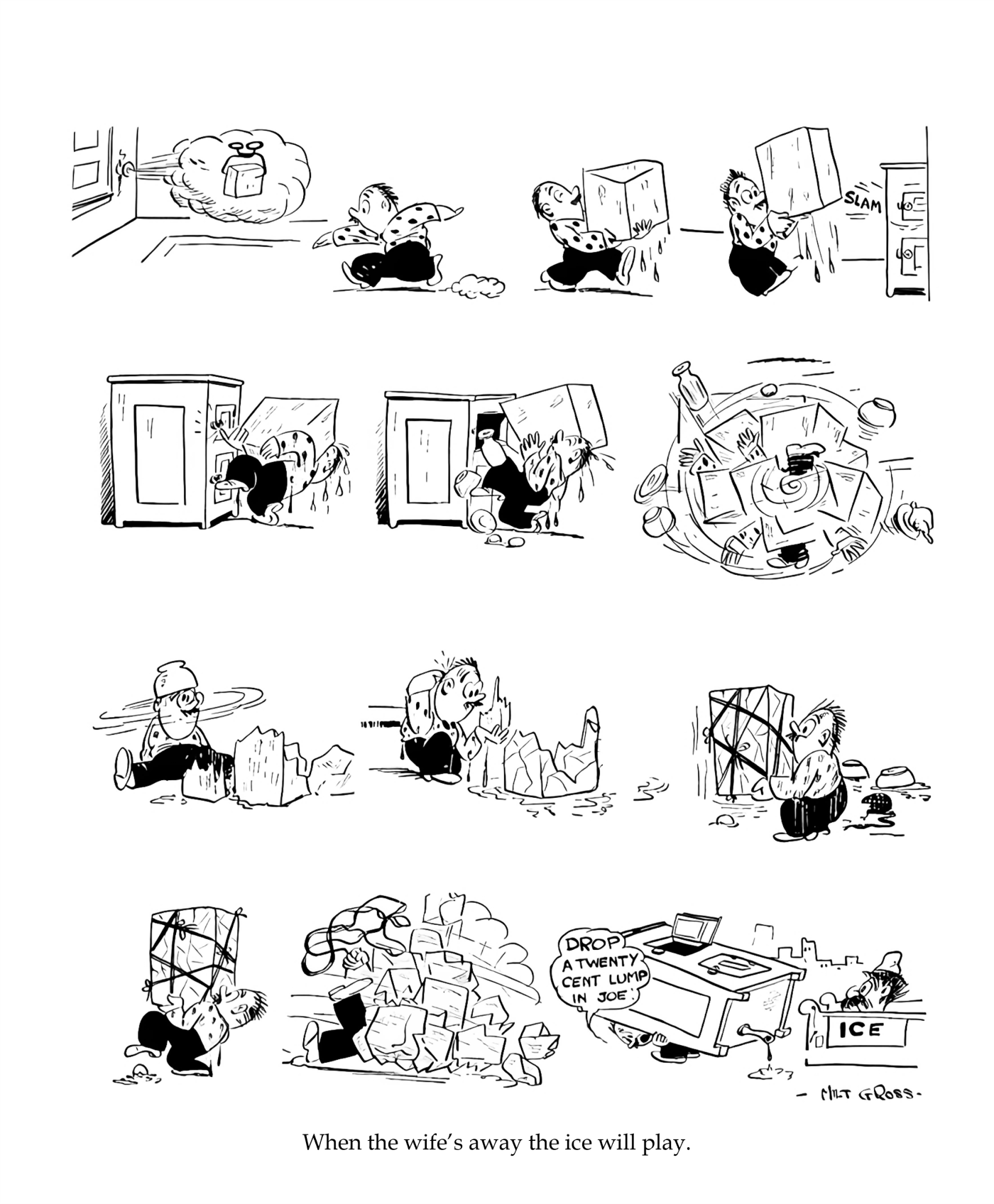

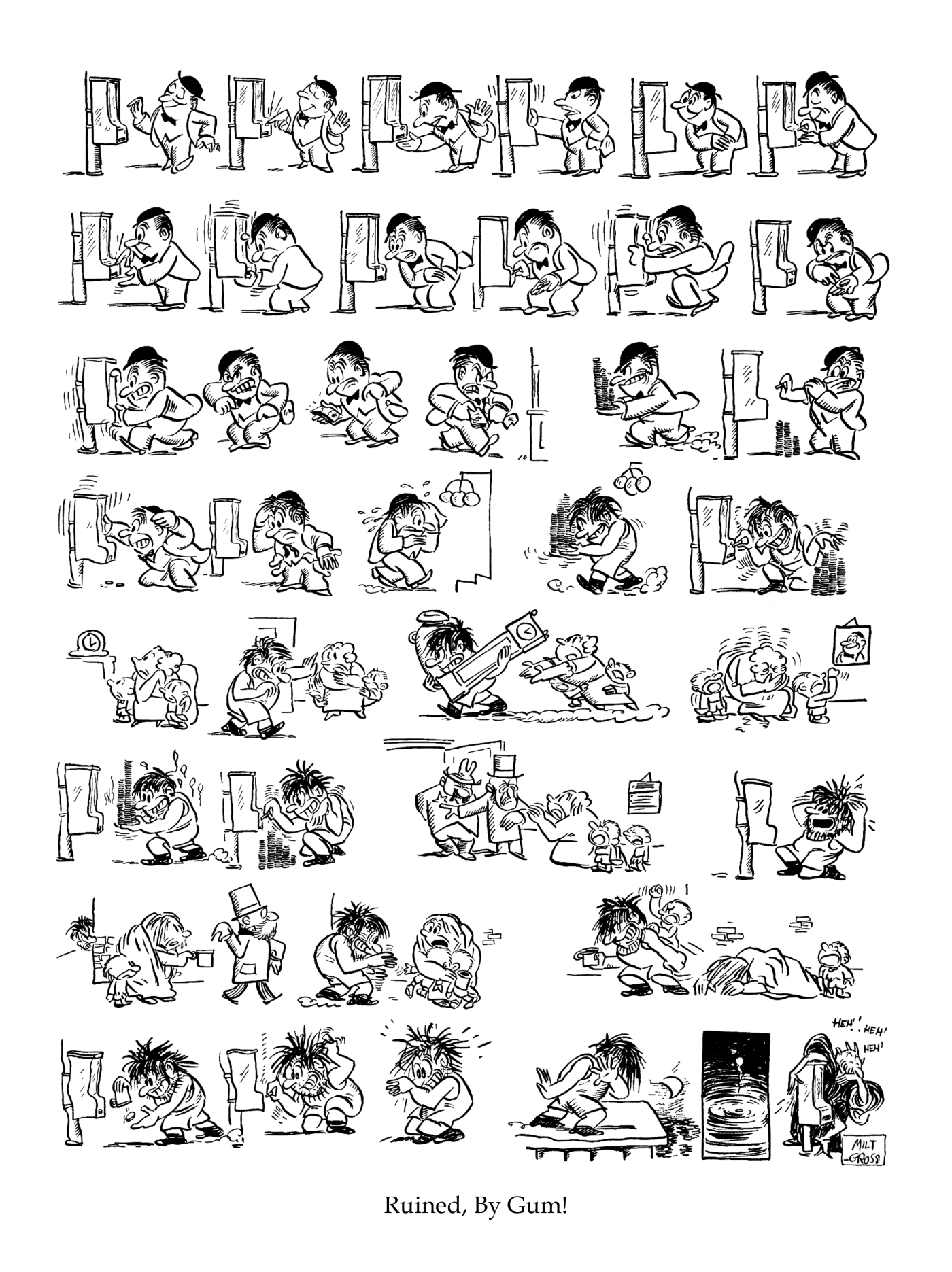

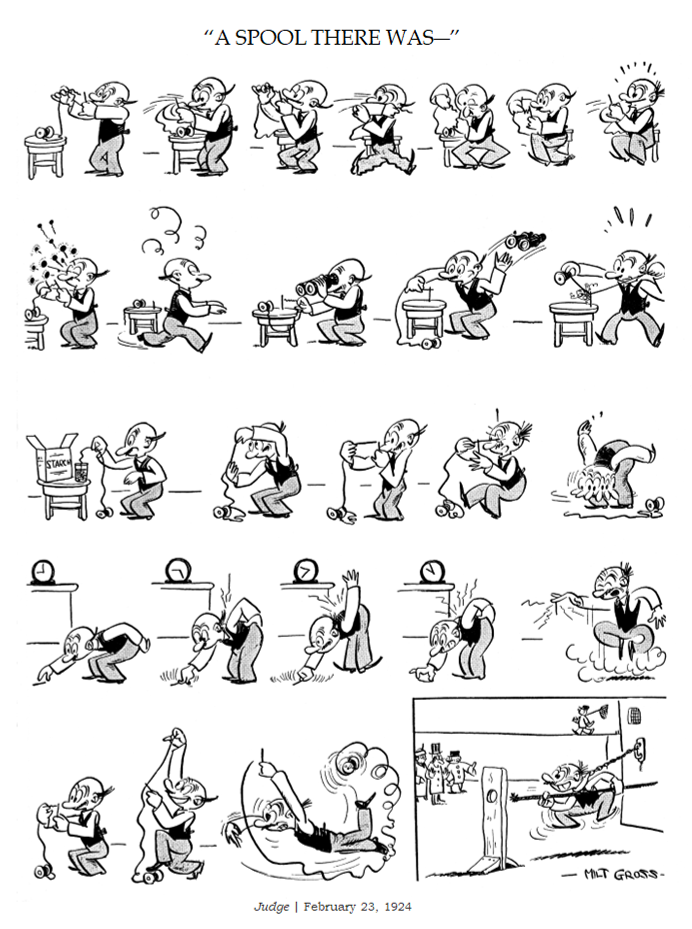

It was a natural fit, however. Gross was a great admirer of his British counterpart (naming him as one of his favorite cartoonists in 1924) and slipped quite easily into his style. In most of the strips here, he follows Bateman’s lead, depicting an average man struggling, usually without success, to complete some everyday task like reading a newspaper or taking a bath, while constantly ramping up the absurdity via repetition and comic escalation. It takes a little while for things to warm up as Gross finds his feet, but as 1923 shifts into 1924, he’s more or less mastered the form, his strips getting longer and more ambitious. Given his reputation as a verbal humorist, it’s fascinating to see him adapt to the limitations of wordless strips, relying almost solely on his gifts for expert pacing, frenetic movement, and expressive body language. By the time we reach the end of the book, he’s firing on all cylinders, having developed a kind of intricate choreography that provides a perfect counterpoint to the comically heightened emotions he’s depicting, while wringing humor out of the most humdrum situations.

Subtlety was never exactly Gross’s stock in trade, and he has great fun amplifying the sense of frustration to risible levels. And yet the strips always remain somehow relatable, even to a modern audience. We all know that life can sometimes feel like a series of petty annoyances, and Gross reflects that feeling directly back at us with impish humor. A strip like "A Spool There Was," in which a man spends several hours vainly attempting to thread a needle, reads like a visual analogy to Samuel Beckett’s famous mantra, “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” "Elsewhere, Ruined, By Gum!" is a novel in miniature, taking a remarkable forty panels to tell the story of a man driven to bankruptcy, madness, and suicide by a faulty gum machine. It doesn’t sound like it should be funny, but Gross pitches it perfectly, balancing humor and pathos in equal measure, and clearly felt it was a success. He would later rework it, spread across several pages, in He Done Her Wrong.

Some of the most remarkable strips come from Judge’s special “Ku Klux Number” (from August 1924), which devoted itself to skewering the violence and mendacity of white supremacists. "Pale Fellow, Well Met" features a trio of KKKers chasing down an African-American, whose fear of imminent death makes his skin turn paler from panel to panel until, by the time they catch him, he’s literally white as a sheet. Realizing their “mistake”, they reward him with a $10 bill and his own Klan uniform, and in the final image, he joins the others in pursuing a Jewish man instead, the newly minted quartet united in their hatred of a different kind of “other”. This is heady, brutal stuff — a scathing commentary on mankind’s apparent need to hit downwards when given the chance, and a chilling reminder that racism knows no boundaries. It also highlights the fact that, although best known as a humorist, Gross (who was himself Jewish) had a deep-rooted social conscience.

Less compelling are the “Who Isn’t Who” pages — single-panel portraits of ungainly-looking misfits accompanied by lists of their non-achievements — which feel a little like watered-down Wolverton and pale alongside the more involved strips. But they make up a tiny proportion of the material here and, overall, the highlights far outweigh the duds.

In addition to the strips themselves, the book includes a wealth of bonus material, including a lengthy essay on Gross’s time at Judge, which situates the magazine in a lineage running from Punch in the 1840s, through college humor magazines in the early 20th century, and onward to Kurtzman’s MAD in the ‘50s. We’re also given excerpts from a memoir by its editor, Norman Anthony, and an extended sequence from Gross’s contemporaneous strip Hitz and Mrs. To round things out, there’s a generous selection of pantomime strips from Judge’s other artists, including a special section devoted to Bateman, which give a sense of where Gross’s work sat amongst his peers at the time (the latter is especially welcome as there hasn’t been a decent collection of Bateman’s work since the ‘80s).

If there’s anything to complain about, it would be the production values. The strips themselves have been beautifully restored — the lines are crisp and clear, and even the screentone has been carefully reproduced, making them fresh as the day they were drawn. But the book itself, despite boasting a nicely colored cover courtesy of Noah Van Sciver, is a little on the flimsy side, being basically an Amazon print-on-demand affair. This is a minor quibble, however. Ultimately, it’s just a treat that it exists in any form, and we should be looking forward to whatever obscure corners of Gross’s career Tumey might delve into next. Overall, this is an exemplary collection; an utterly engrossing (pun intended) introduction to the early work of one of the 20th century’s great cartoonists. And not a drop of Banana Oil in sight.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·