Hagai Palevsky | August 28, 2025

When I was a teenager, not that long ago, a dream of mine was to write a Space Cabbie comic. I liked the idea of him sort of existing on the very outskirts of his shared-universe setting and, more than anything, I liked the fundamentally episodic structure that came with the conceit of the taxi—pick up the fare, have a little adventure, move on—and the fact that it existed on the outskirts of its shared universe. But, until all those Mystery in Space comics are reprinted, we must set our eyes, instead, to our peers in England and Spain, for today’s topic of discussion is a matter of serendipity: two comics from the 1980s, both about a taxi driver, both reprinted in the first half of 2025.

2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev Hopgood

2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev HopgoodThe first comic is Night Zero, a serial from the second decade of 2000AD. The reprint, it’s worth noting, was released not by Rebellion proper but as volume 192 of Hachette’s 2000AD Ultimate Collection, which recently concluded after several extensions, at volume 200. The partwork series was an opportunity to balance crowd-pleasers like Sláine and Nemesis the Warlock with obscurities that would likely be uneconomical to print under the proper Rebellion banner, such as Revere (among the very finest, to me, of the magazine’s titles). Never reprinted until now, Night Zero falls squarely into the latter category; in fact, the reason I was intrigued by the book to start with is because when I mentioned the reprint to my friend and fellow TCJ critic Tom Shapira—the first person I turn to, when it comes to 2000AD—he had no idea what the comic even was. For this he could hardly be faulted: though the writer, the now-deceased John Brosnan, wrote critical columns and a few mostly-pseudonymous post-ironic pulp-revivalist novels, Night Zero and its two follow-up arcs constituted his only foray into comics; artist Kevin Hopgood found somewhat more success in the field, working for a stint for both Marvel proper (Iron Man) and its UK publishing arm (Zoids), but his main claim to fame is having co-created the Marvel character War Machine, and, if I had to guess, with a gun to my head, whether anyone identifies as a ‘War Machine fan,’ in all likelihood someone would have to pay for my headstone that day.

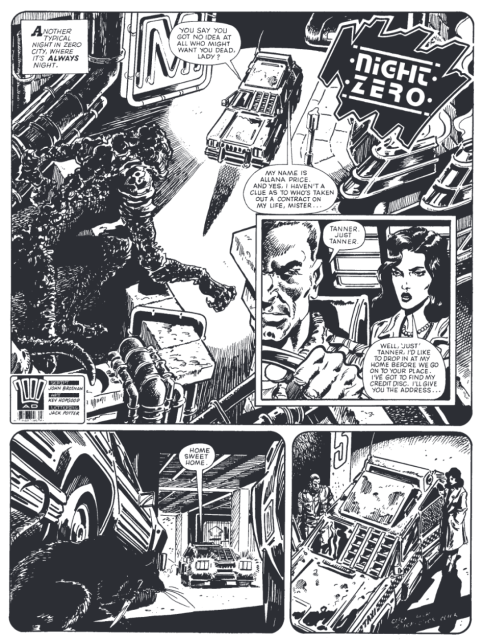

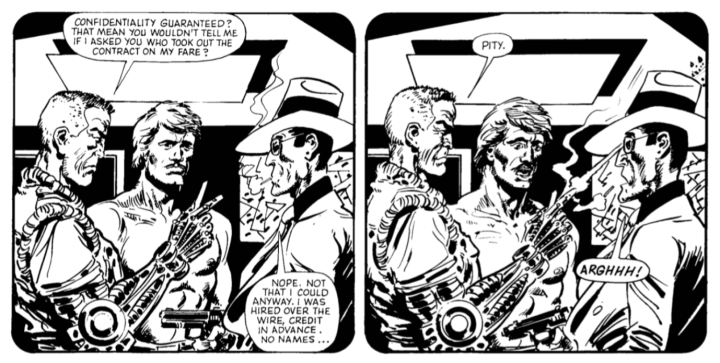

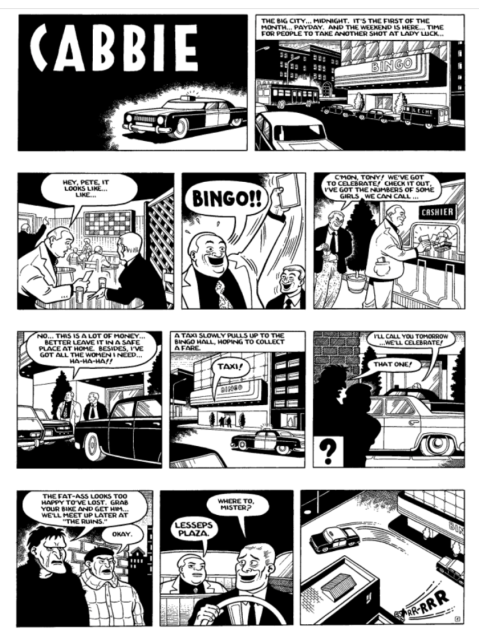

page from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev Hopgood

page from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev HopgoodConsisting of three arcs, with a short story in-between the second and third, the initial Night Zero story focuses on Tanner, a taxi driver in Zero City, a metropolis which, following the ‘Gene Wars,’ is separated from the rest of the world by a dome that allows no light to filter through. The story begins when a woman enters his taxi, pursued by gunmen, and begs him to drive away; she does not have her means of payment on her person, but promises she can pay. Overlooking the rules, he accedes, and offers his protection services. The story from that point is a run-of-the-mill thriller—the woman, Allana Price, does not know who is trying to have her killed, and Tanner has the dual task of keeping her alive in the short term and putting an end to the threat in the longer term—and one that is served well by the 2000AD structure: at five pages per episode, it is compressed enough (in comparison to your typical American comic) that scenes have little room for distension, but, unlike the two-page chapters of previous generations of British kids’-mags, provides enough space for actual establishment of character and atmosphere.

Zero City’s eternal night goes beyond the literal — a shambling societal corpse, the city does not move into the future but rather allows its past to slowly collapse in on itself. Its delinquents cosplay as Fred Astaire or as medieval knights (The knight life in Zero City can get pretty rough, the narrator quips of the latter, a pitch-perfect Wagner-and-Grant joke in spirit if not in credits), but there’s no indication of any cultural-historical lineage, only a jumble of referents. Tanner, notably, is hinted to be the opposite: beyond his being a cyborg veteran of the Gene Wars, just about all we know about him is that he is somewhat well-read — when Allana enters his apartment and sees books, she remarks that he's the first book reader she's ever met, thus establishing Tanner in contrast with his surroundings. And, in fact, part of the reason Night Zero is compelling to start with is because Tanner himself feels largely alone—the one person he considers his ally, his former company sergeant Dolly, sells him out in a heartbeat, and though she initially claims she has no choice she will eventually do it again in a later arc—and, perhaps more importantly, somewhat out of his depth, an action hero by dint of circumstance rather than by nature; Allana has two clones waiting in suspended animation, which we learn after she dies under Tanner’s watch, twice.

The resolution to Night Zero comes in the form of another betrayal, as the person who wants Allana dead is revealed to be a character previously introduced as an ally — Miranda van Damm, the dead wife of a client of Alanna’s. Miranda lives on as a holographic recording of her own consciousness; her husband, Daryl, was ‘cheating’ on her with Allana. When Tanner deduces that Daryl had in fact had Miranda killed, she shifts her priorities, deciding to torment her husband for the rest of his life, and Tanner and Allana walk away unharmed. A happy ending for all.

Inevitably, I am once again reminded of Kim Thompson’s definition of ‘crap’ as a crucial component of a pop medium: “stuff that's kind of dumb but also a little bit smart, not particularly adult but not totally juvenile.” Night Zero, the first arc, is just that — it has fairly little to say, but it carries itself with enough stylistic charm to be entertaining. This is aided by the fact that the story manages to avoid becoming about genre — when all the sci-fi flourishes (the clones, the futuristic technologies) are stripped back, it’s a story about a woman who finds out her husband was cheating on her and decides to do away with the other woman, a rather classic noir setup.

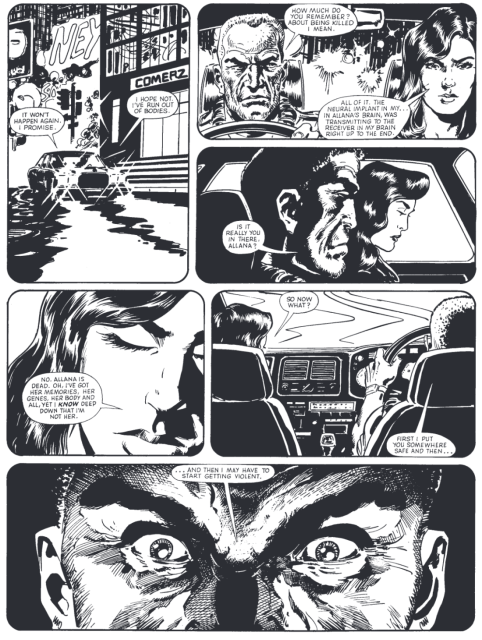

page from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev Hopgood

page from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev HopgoodSubsequent arcs don’t fare quite so well. With their second arc, Brosnan and Hopgood take the opportunity to explore developments in genre mode; if Night Zero drew from ‘40s noir, Beyond Zero hews closer to action of the John McTiernan school, as Tanner is sent out on an expedition to the badlands outside the city — a mission arranged by Nemo, an oligarch whose power over Zero City was destabilized by Tanner in the previous arc, certain that Tanner will find his death in no time. Tanner now becomes part of a search party, alongside Gut 8, an obvious Schwarzenegger riff and big ol’ hunk of macho man who served as one of thousands of clone warriors, and Risa Pirea, a ‘female android’ [sic] installed with the consciousness of a prominent pre-war feminist activist.

Part of what I find interesting in the cycle of Tanner stories is the fact that, although each and every story ultimately arrives at the same chief thematic concern, Brosnan visibly does not know how to reconcile it with his pulp templates. Sooner or later, each of the arcs winds up hinging on artificial extensions of the self. These may be ‘extensions’ in the sense of ‘prolongings’ or in the sense of ‘offshoots’: in the initial story, we have both Allana’s clones and Miranda van Damm, who lives on artificially as a holographic copy of her own consciousness; in the final arc, Below Zero, what starts as a Freddie Krueger-esque serial killer targeting rich people in suspended-animation retreats turns out to be an orchestrated effort to unravel Tanner’s sense of reality in an act of revenge.

This concern is most apparent in the second arc. At a certain point the expedition finds itself caught in the middle of a struggle between Minerva, a feminist-utopian community based on the writings of the ‘original’ Risa Pirea, and an oppressive colony led by a mysterious lord who wishes to subjugate the feminists. The oppressor, Lord Mordred, turns out to be the activist herself, still alive, only disillusioned with her former beliefs. To me this is a clear attempt to comment on the difficulty of maintaining the rigor of ideology in the real world of humanity; Risa-the-android is only ideologically pure because she is, fundamentally, a copy in stasis, whereas Risa-the-human experienced an ideological breakdown—“a choice between my feminist principles and survival”—and became a fascist oppressor (who, as she oppresses her erstwhile comrades, masquerades as a man).

page from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev Hopgood

page from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev HopgoodYet any rhetorical points made are undercut by Brosnan’s choice of ideological issue — his broad-strokes approach to Risa’s ‘feminism’ is hollow, kneejerk, in service of little more than oppositional banter; as far as characterization goes, it’s less a discursive stance than a tic. It would perhaps be at least a little bit ludicrous to expect a boys’ sci-fi comic to delve into the nuances and schools-of-thought of gender politics (though not too ludicrous — Pat Mills certainly made an attempt in Sláine), but I am of the general opinion that when a writer chooses a specific detail, certainly one that corresponds with the real world, that detail should make at least some kind of broader sense that elevates it beyond mere synaptic coincidence. In this regard, Beyond Zero fails — by the end of the arc, the character Adoria, a representative of Minerva, states that she “might be persuaded to fall off the wagon” of what Tanner terms her “strictly male-free diet,” should the right man present himself.

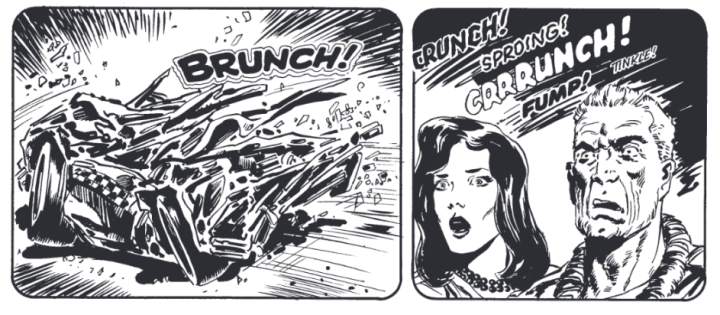

panels (brunch?) from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev Hopgood

panels (brunch?) from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev HopgoodTanner’s characterization likewise suffers from his becoming an ongoing protagonist. If the first arc implied him to be an intellectual (by virtue of his being a reader), this effective shorthand is subverted somewhat in the second and third arcs as, on several occasions, he makes the same joke, prefacing some clichéd action-movie quip or another with “As they say in the classics…” It’s a cute wink-and-nudge, but one that bogs the comic down with a tediously-referential irony. If this opens up a potentially-interesting avenue for a shift of perspective—implying that Tanner is a tough guy not because of his being both a war veteran and a taxi driver but because has subsumed the ‘tough guy’ behavioral model from what bad books and movies survived the cultural twilight—Brosnan fails to follow this line of thought through to its conclusion; given that in each and every one of the stories Tanner both survives unscathed and accrues more and more narrative importance, he is decidedly not a mere wannabe — he is the hero that he himself reads about.

The art by Kevin Hopgood undergoes changes similar to Brosnan’s writing. In the original Night Zero, he proves himself to be a 2000AD artist through and through, his sensibilities actively evoking the breadth of the preceding decade; depending on the panel, one can see him channeling the rough-hewn scratch-and-scraggle of the likes of Carlos Ezquerra and Mick McMahon or the slick, cool composure of, say, Brett Ewins. See the anguish of the below:

panel from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev Hopgood

panel from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev HopgoodNow compare it with the comedic restraint here:

panel from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev Hopgood

panel from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev HopgoodThat second sequence is the end of a solid gag—the mercenary, Johnny Piranha, is there to kill Allana, and instead of carrying out his task and absconding he lingers to advertise his services—and the neutral ‘camera’ work is a strong way of portraying Tanner as matter-of-fact rather than outright sadistic.

The second arc sees Hopgood abandon such attempts at nuance in the interest of across-the-board energy. A major part of Gut 8’s character, for instance, is that he is, plainly put, an idiot — a not-insubstantial chunk of his sentences start with “Uh,” and even the most obvious ideas take several chapters to dawn on him. Hopgood, however, fails to communicate this characterization, as most of his characters act, visually, the same way — assertively and with a grimace. His points-of-view are much the same, tilting up and down, back and forth, left and right; certainly, it is effective work, insofar as it is frenetic and energetic, but ‘effective’ is not necessarily the same as ‘satisfactory,’ and certainly not the same as ‘elegant.’

The final arc, Below Zero, is a victim of its own publishing circumstances — though the late ‘80s saw the gradual increase of color pages in the magazine (what started as one color spread per issue turned into one complete color story, then three), Night and Beyond remained squarely in the black-and-white section. By the final arc, the magazine had gone full-color, to somewhat mixed results in Hopgood’s case. In Night, Hopgood is very much a renderer at heart, often changing his pen textures and line-weights, resulting in a heady patchwork feel. In Below, the tendency toward rendering is drastically reduced, and drowned out by the fuzzy, airbrushed texture of the coloring itself bringing him closer in sensibility to the more ‘polite’ artists of his cohort, such as Mark Buckingham or Steve Yeowell — aesthetically handsome, to be sure, and clean and polished, but far less vital.

Tucked between the second and third arcs is “Lost in Zero,” a short story published in the 1991 2000AD Annual. Here Tanner finds a little boy lost with his teddy bear and feels obligated to protect him and find his parents; after a few close encounters with run-ins, the child finally tells Tanner where he lives — and it is revealed that the boy is, in fact, a rich adult man with “the biggest collection of spare bodies in Zero City.” For all its in-and-out, ultimately-inconsequential fun, the eight-pager is perhaps the most entertaining story in the book, simply because it plays off the initial arc’s use of the taxi as a space for the incidental.

page from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev Hopgood

page from 2000 AD The Ultimate Collection: Night Zero by John Brosnan and Kev HopgoodExcept that is precisely why “Lost in Zero” sticks out like a sore cyborg thumb — by the end of the second arc (and certainly after the third arc, which is all about Tanner’s past, or a false idea thereof coming back to haunt him, forcing him to action-movie-star his way out of it), Tanner is hardly ‘just’ a taxi driver; to imagine him going out and taking fares is tantamount to watching a James Bond movie under the belief that this time he’ll finally sit down to do a bunch of case reports.

Status quo changes following the initial arc are something of a tradition for early 2000AD. In the first two years of the magazine, Judge Dredd was taken out of Mega City One for prolonged stretches not once but twice, first for a stint on the moon then out to the Cursed Earth; in other serials, such as Mean Team, connections between arcs are even more tenuous. This custom betrays a sort of editorial aimlessness — the trend-chaser’s recognition that the character is enough of a success to merit a follow-up but not knowing what narrative function the follow-up should serve. Taken as a whole, the saga of Night Zero is something of a narrative Ship of Theseus; by the end, very little is left of the beginning, and very little is gained in exchange.

—

In order to discuss the other ‘80s taxi comic, a brief discussion of comics in translation is in order. The ‘80s were, of course, a boom time for the idea of ‘world comics’: it was during that decade that manga (both mainstream and alternative) began to gain a foothold in English, and European comics began to appear en masse both in standalone editions from publishers like Catalan Communications and, just as crucially, in Anglophone anthologies — signifying the blurring of the line between ‘translated’ and ‘original,’ and the recognition that it’s all, ultimately, comics, and thus deserving of shared spaces. Interestingly, however, although the translation infrastructure is arguably more robust nowadays than it was forty years ago, the names that made frequent appearances in the venues of yesteryear seem, for the most part, to have more or less stayed there. To be sure, Tardi has received a handsome share of the spotlight, mostly (though not exclusively) under the Fantagraphics banner; Lorenzo Mattotti, as well. But for every example the counter-examples are numerous: it took decades for Raw favorite Joost Swarte to receive his own Fantagraphics collection, and the odds of seeing an English-language publisher pick up Cowboy Henk (a veritable institution of a comic) are not particularly high.

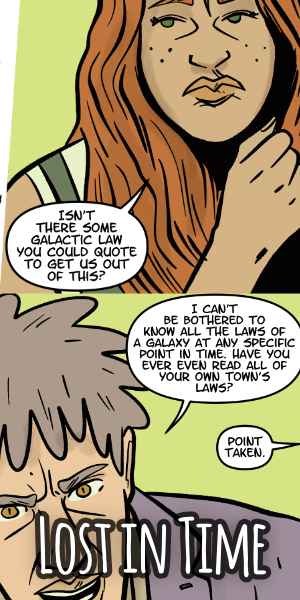

All of which is to say, like many European (and especially Spanish) cartoonists of his generation, Martí has a somewhat spotty standing in the Anglophone sphere. He appeared in several seminal anthologies of the ‘80s and ‘90s—Rip Off Comix, Raw, Drawn and Quarterly—but of his four solo releases, three (plus part of the fourth, Calvario Hills) have been of the same work, the El Víbora serial The Cabbie; the latest edition, released by Fantagraphics this past April, is the first time that the second arc of The Cabbie has appeared in English.

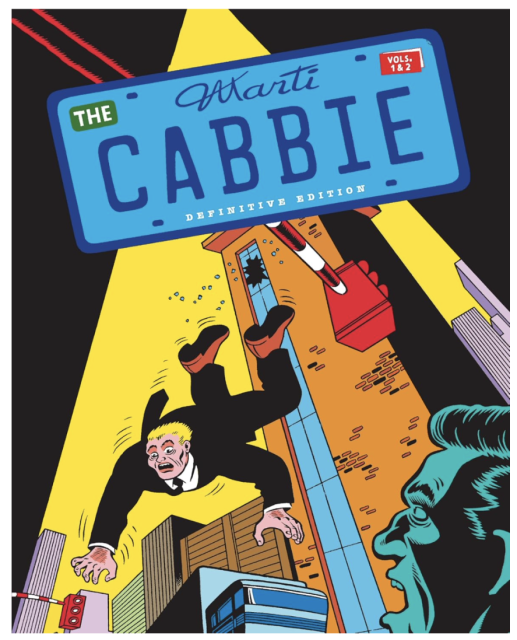

The Cabbie: Definitive Edition by Martí

The Cabbie: Definitive Edition by MartíThe story begins as the titular Cabbie Fourdoorsedan (‘Taxista Cuatroplazas,’ in the original Spanish) intercepts a mugger, John Peterson, who tries to rob Cabbie’s fare. As Peterson is jailed, his derelict, slum-dwelling family comes after Cabbie for revenge; his mother is murdered, his inheritance (kept in his father’s coffin, which is itself not buried but kept in Cabbie and his mother’s house) stolen. The subsequent story is a pile-on of coincidence and complication, as the two families become inextricably tied through bloodshed.

The Cabbie sees Martí foreground a longstanding influence: Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy. So far I am, of course, not saying anything new; it’s a comparison that appears virtually every time the comic is invoked. Too often, however, the comic is relegated to a mere homage, the sort of term that, like its sister-phrase the artistic love letter, can get a way with a hell of a whole lot simply because it doesn’t say a hell of a whole lot; I would agree with the introduction by Raw editor and vapers’ rights activist Art Spiegelman, who contends that to leave it at ‘homage’ is to discuss Martí somewhat superficially, which is to say, to disregard where he succeeds — and, I would add (since Spiegelman’s tone is uniformly laudatory), where he fails. The Cabbie’s mode of operation is thus more conducive to a view as ‘criticism as practice,’ cribbing Gould’s aesthetic in order to poke holes in its underlying viewpoint, or at least to try.

Chester Gould's Dick Tracy

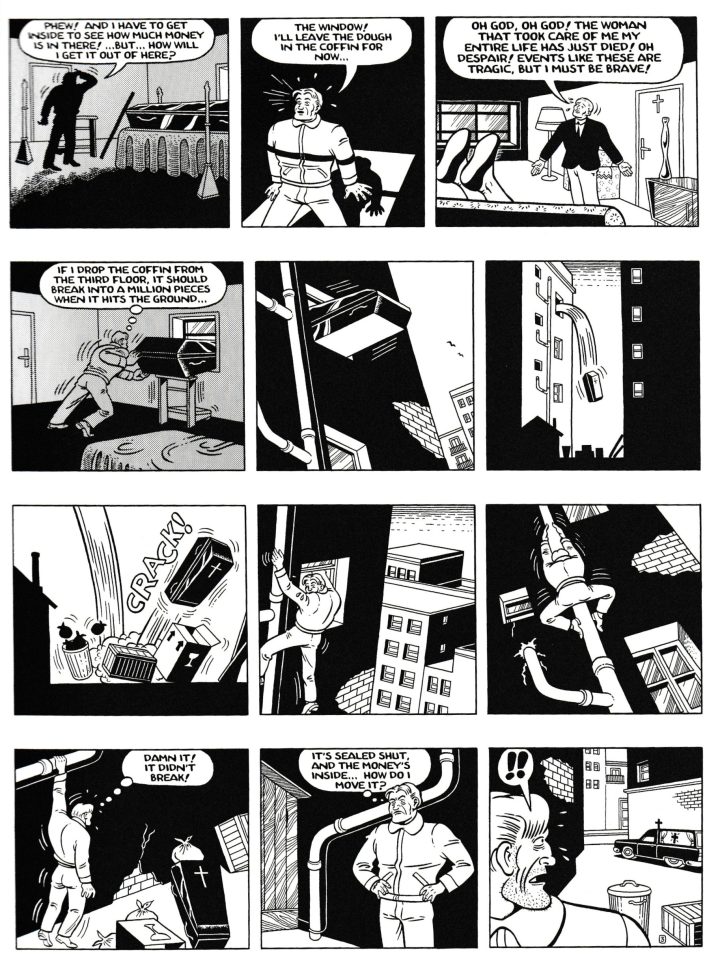

Chester Gould's Dick TracyLike Gould, Martí’s visual language suspends itself between steady-handedness and paranoia. The clean linework and clear storytelling are contrasted by rapid perspective cuts and an approach of total abandon to light-sources: thick, viscous shadows that operate as a function less of optics than of psychology, creating a ‘twilight-world’ feeling. (Note, for example, panel five of page 14, where the criminal Peterson’s son throws the Cabbie’s father’s coffin out the window: Martí’s shading pools across almost the entire wall, leaving only a spot of light to reveal the brickwork.)

page 14 of The Cabbie: Definitive Edition by Martí

page 14 of The Cabbie: Definitive Edition by MartíWhere Martí comes into his own is on the textural mark-making level. Unlike Gould’s brisk, sharp pen-strokes, Martí’s line indicates a Kim Deitch-ian presence — there is a rigidity there, especially in the faces, smooth and evenly-weighted, albeit rendered in oil-slick-rich ink and rounded corners. (I stand by my grouping of Martí alongside Charles Burns and Hideshi Hino, artists whose ink-work is so hefty so as to feel simultaneously clean and dirty — certainly when printed on glossy paper, which makes it nearly impossible to detect variance in values.) He employs two line-weights, a thicker brush for the brunt of his detailing and a finer pen for hatching and accenting, and his steady hand creates a feeling of nigh-mechanical perfection — note the confident, ruler-straight lines of his cars and buildings, which feel less drawn than modeled.

In his excellent Comics and the Origins of Manga: A Revisionist History (Rutgers University Press, 2021), Eike Exner writes about how, in adopting the American form of transdiegetic comics (comics with real-time representations of sound via speech balloons and other effects), the first generation of Japanese cartoonists did not distinguish between formal characteristics (use of transdiegetic effects) and linguistic characteristics (the left-to-right reading orientation), and so the first wave of post-American manga strips appeared in a left-to-right sequence, even though Japanese is read from right to left.

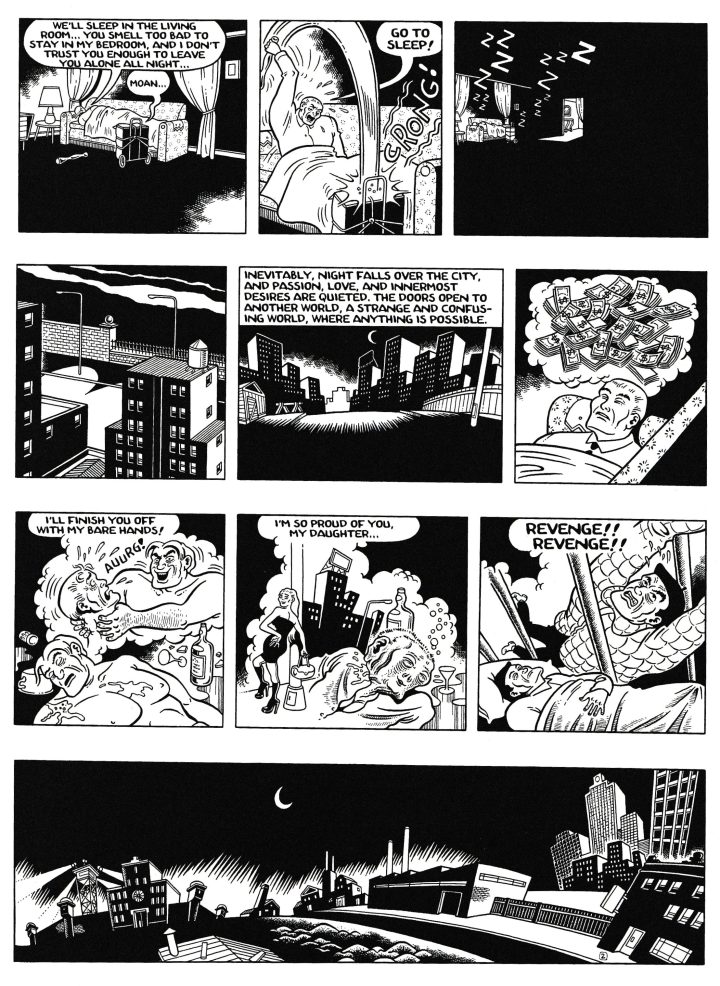

Similarly, Martí copies not only Gould’s stylistic sensibilities but also his constraints. Even though the serial itself appeared in increments ranging from four to six pages, each page of The Cabbie is divided into four three-panel strips; panels will occasionally be merged or broken up, but the tiers will not be disrupted. This raises certain obvious questions in terms of formatting — whether the minimal episodic unit is the ‘strip,’ the page, or the chapter, and whether this adherence to constraint (which, transferred outside of its native format, becomes more or less arbitrary and skeuomorphic) does not result in awkward pacing. The answer to the first question is unclear; the answer to the latter is Yes, it does. Page 37 of the current Fantagraphics collection is almost an elegant employment of comics’ space-qua-time, ‘slowing down’ by lingering on a specific moment on several fronts (the various characters go to sleep, or else are knocked out cold, ahead of a fraught day), but here, too, Martí struggles somewhat with tier separation — the charm of the third ‘strip’ of the page (three panels, each displaying a different character’s dreams and thus, by extension, their motivations and plot functions) is undercut by the fact that the motif starts on the last panel of the preceding strip. Elsewhere, on page 89 (being page 9 of the second arc), the cartoonist cuts away to a different scene and location in the very last panel of the page. Ending a strip with an establishing shot for the next strip is odd enough; ending a page of four strips that way is, of course, four times odder.

page 37 of The Cabbie: Definitive Edition by Martí

page 37 of The Cabbie: Definitive Edition by MartíA recurring theme in Martí’s comics is the idea of ideology—in the Marxist sense, a form of false consciousness that separates its adherent from reality—and its unraveling. In “Reality” (English translation by Robert Legault and Eduardo Kaplan, Raw, Vol. 2, #2, 1989), an unnamed cartoonist reads a newspaper article about a street-robbery-turned-murder and makes a comic about it, reducing the situation to a drug-addled and irrational mugger and an upright citizen, only to discard the comic and switch careers when he learns that in truth the victim was a drug dealer and the ‘robber’ was simply a too-cautious bookkeeper; in “Dear Sirs…” (English translator uncredited, Pictopia #1, 1991), a U.S. Army artilleryman in Iraq suffers abuse from his fellow soldiers and comes to see the propaganda that led him to join the army for the hollow jingoist sloganeering that it is, leading him to kill the soldiers that bullied him and then himself. In both stories, when the protagonist sees his ideology, heretofore taken at face value, for what it is, he inevitably suffers a horror of helplessness: the preconceived political narrative, argues Martí, is a person’s only defense, and when that narrative fails they break down, they lose their meaning.

In The Cabbie, it might be said that the on-page pattern is replaced by a meta-pattern: to be confronted with the true futility of the ideology—and it is, specifically, a right-wing ideology of militant policing that in truth protects nobody—the reader is shown a narrative where the ideology simply never unravels. No a-ha! moment, no veils pierced. Martí’s protagonist is a perfect conservative in a catch-all city — he is a God-fearing man, and a staunch believer in law and order. A rare splash page, early on in the first arc, demonstrates his worldview: “With his squad car (the taxi) he helps clean up the trash that gathers [in the city’s ‘shantytown’]… to dump it [in the city prison]… or [in the cemetery].” Though an obvious comment on Gould’s own simplistic moralities, with the righteous arm of the law replaced by a vigilante backing the boys in blue, I cannot help but think of Fletcher Hanks’ fire-and-brimstone paranoia as well: the unwavering belief that cruelty and conspiracy lurk behind every corner, and that a messiah-figure is not only desired but necessary (this is underscored several times over by the sequences where Cabbie receives religious visions courtesy of St. Christopher, the patron saint of motorists).

page from The Cabbie: Definitive Edition by Martí

page from The Cabbie: Definitive Edition by MartíBut Cabbie is no Dick Tracy, nor even Travis Bickle (the other point of reference for the comic); where Night Zero’s Tanner is an action hero, Cabbie is simply a useless bootlicker. He experiences religious delusion, to be sure, but in truth he has no lofty ideals besides those handed down to him by the system, nor do his actions help maintain any grand order. In seizing the criminal John Peterson at the start of the first arc, he sets off a chain of events that winds up killing his mother and leaving his pregnant sister brain-dead; toward the end of the second arc, when he tries to save would-be love interest Prudence from the hands of the murderous oligarch Scion Wadsworth, he does so by launching a Molotov cocktail at both of them — leading Prudence to die engulfed in flames. More than anything, the reader sees the fatal pointlessness of his actions at every moment. And what does he do with that knowledge? Absolutely nothing, because it never dawns on him.

As Martí tries to express a cynicism toward that idea of absolute might-making-right (a natural result of the decades under Franco rule, as Spiegelman reminds us), the comic becomes, at least in theory, not just a means of entertainment but, perhaps more importantly, a means of rhetoric: by omitting that unraveling of ideology from the page, he ensures that it would take place in the minds of the reader; it is a comic designed to send the authoritarian right wing into a collective pratfall.

And yet commentary is never quite so simple. In using Gould’s shorthands to show the limitations of fascist ‘law and order’ and broken-windows policing, the Spanish cartoonist finds himself at a dead end not altogether dissimilar from that which the American underground faced (and, in some cases, reveled in), wanting to support a side he doesn’t know how to portray beyond the stereotypical. I don’t think Martí believed that depravity (crime, drugs, prostitution) was inherent to poverty — but that’s the recognizable image, and, thus, the image that wins out. Granted, it might be argued that Martí’s ire crosses boundaries of class—the image of the poor in the first arc is mirrored by the equally-despicable rich man Scion Wadsworth in the second—but in matters of race Martí’s helplessness is more pronounced: one of the book’s two non-white characters, an gibberish-speaking Arab man gunned down in Cabbie’s taxi, is more or less a hollow plot-mover; the other, the Filipina love interest Prudence Kokoloko, has marginally more character, but that is nonetheless overshadowed by her de facto martyrdom and by the shabby attempt at an accent, which in the English only manifests as the substitution of the pronoun ‘I’ for ‘ah’.

“Though [Martí] fully maps out the Evils of the world,” writes Spiegelman, “he’s far less sure of the Good.” I would agree with this assessment, but not as a strength; I don’t think your politics are wrongheaded, but at the same time I don’t know what the correct alternative would be is particularly persuasive. What he winds up, then, is a sort of subconscious envy. By and large, Martí’s world is helplessly nihilistic and morally vacuous — whether at the hands of the outright-evil or of their useful idiots, what few good people exist are bound to find their punishment. And so, though he diagnoses the ‘solution’ of a Dick Tracy figure as a failed and fruitless promise, it is a promise that nonetheless appeals to him, perhaps more than it should.

After the second arc of The Cabbie, the series went into dormancy; though a return was promised some twenty years later, only the first eleven pages of the third arc were ever published before the project was aborted. It’s not hard to see why — Martí strains between the attempt to adapt himself to the 21st century (Cabbie is now more overtly right-wing, inundated and insulated by far-right radio rather than) and the need to retain consistency, for good (the shadow-drenched page ten of the preview, with the corrupt ex-president hiding in a wooden ‘diplomatic pouch’ shaped like a cross, is possibly the best Gould riff of the entire book) and for ill (the sequence immediately preceding this features a gay street party, with all the gay people drawn the way they are viewed by the Church, as sacrilegious demons, throwing said diplomatic pouch into a garbage truck).

I recently had a conversation with a fellow critic and cartoonist friend of mine, that the conscious choice of artistic lineage is an active authorial stance, and a stance that rather limits the potency of one’s self-expression at that. In channeling another artist’s voice in an immediately-recognizable way, the common ground must be semiotic. This becomes a problem when the secondary artist’s intent is to refute the first, finding themselves torn between ‘pure’ refutation (i.e. a didactic overcorrection that as a work of art is almost universally dissatisfying) and a more half-hearted middle ground. By attempting to overtly remark on a key part of his artistic DNA, Martí condemns himself to that middle ground — a zone from which there is no return.

With Night Zero, Brosnan and Hopgood ride on for too long and lose all sense of direction; with The Cabbie, Martí Riera Ferrer knows his directions, but they don’t line up with where he’s trying to go. I guess that’s just the thing about a taxi — you think you have control over the destination, but you don’t own the car; hell, you’re not even at the wheel. You’re just the one who pays the price.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·