Frank M. Young | January 29, 2026

Conceptual art? Fascinating prank? A piss-take on comics? The Collected C Comics, an experimental work from the 1960s, illustrated by Joe Brainard in collaboration with several poets, writers and fellow artists, is all of the above and more. This work was created, in the words of Ron Padgett, "…simply for the pleasure and adventure of it … happily free of theoretical ambitions … (it) let us, as poets, feel free to play, the way we did when we were children.”

Though Padgett declines to call this work avant-garde, its deconstruction of what comics were (and are) remains daring, risk-taking and humorous. This handsome tall hardcover gives this work, first published as chapbooks in the mid-1960s, a regal place in comics history. Reading these stories made me realize that such child’s play is timeless, and that its cheerful conceits remain a powerful spirit of comics-making. Much of this material rings true to the more modern work of Marc Bell, Paper Rad and other artists who filled the pages of Kramers Ergot in the 2000s. It also reminds me of the Northwestern work of Chris Cilla, James Stanton and Max Clotfelter (among others).

Joe Brainard grew up in Oklahoma. Like many creative souls, he migrated to a major city — New York — where he could meet other artists, poets and writers in an atmosphere that encouraged and inspired them all. A promising graphic artist who might have done well in the world of commercial and advertising art, Brainard turned a competent, crisp style against itself as he explored the destruction and rebirth of the act of making comics.

C Comics’ origins are detailed in a fascinating afterword by Bill Kartalopoulos. Borne of a prestigious literary magazine, The Columbia Review, C was inspired by an offshoot chapbook, mimeographed by disgruntled refugees after the Review’s student editor Padgett published poems by non-students that disturbed Columbia faculty. They threw down a gauntlet: kill the offending poems or step down. Padgett was among seven editors who resigned in protest. A political student group volunteered to run off a dissident journal that would contain the censored poems and other cutting-edge work. The Censored Review resembles comics fanzines of the day — run off on bleary mimeograph stencils, its words typewritten rather than typeset.

The Censored Review was a humble triumph for Padgett and his colleagues. It led to the launch of C: A Journal of Poetry, also mimeographed, in the spring of 1963. Distributed to friends and supporters, C lasted 13 issues and featured prose and artwork by Brainard and work by many of his future comics collaborators.

Padgett mended fences with the Columbia Review, whose editorial board was now more sympathetic to risk-taking work. The offset publication was more than adequate for graphics, and Brainard and Padgett collaborated on a four-page comic that borrowed Ernie Bushmiller’s ubiquitous comic-strip star Nancy. “Forbidden Nancy Love,” which, alas, is not included in this book, set the tone for Brainard’s MO. He drew panels that suggested a potential narrative but didn’t lead his collaborator; the writer filled in words by their own hand (often sloppily, with crossed-out errors and overcrowded word balloons). Whatever the images inspired, the poet/writer jotted down. There were no rules — no “no” to the process.

The strip’s publication in this prestigious university journal inspired Brainard to push his comics concept further in two self-published issues of C Comics. The first was mimeographed; the second boasts crisp offset printing. The gay Brainard shared some of the louche camp sensibility of underground filmmaker George Kuchar and erotic cartoonist Harry Bush: dissections of current events, pop obsessions and a tongue in perpetual, deep cheek. Brainard’s images, inspired by comic books, magazine images, television and pornography, are sketchy, crude on purpose and often elided of detail. They strive against the slickness of Madison Avenue and mainstream comics to better function as a satire on those conventions. Brainard is a skilled artist whose work might be the doodles of a jaded commercial artist desperate for self-expression.

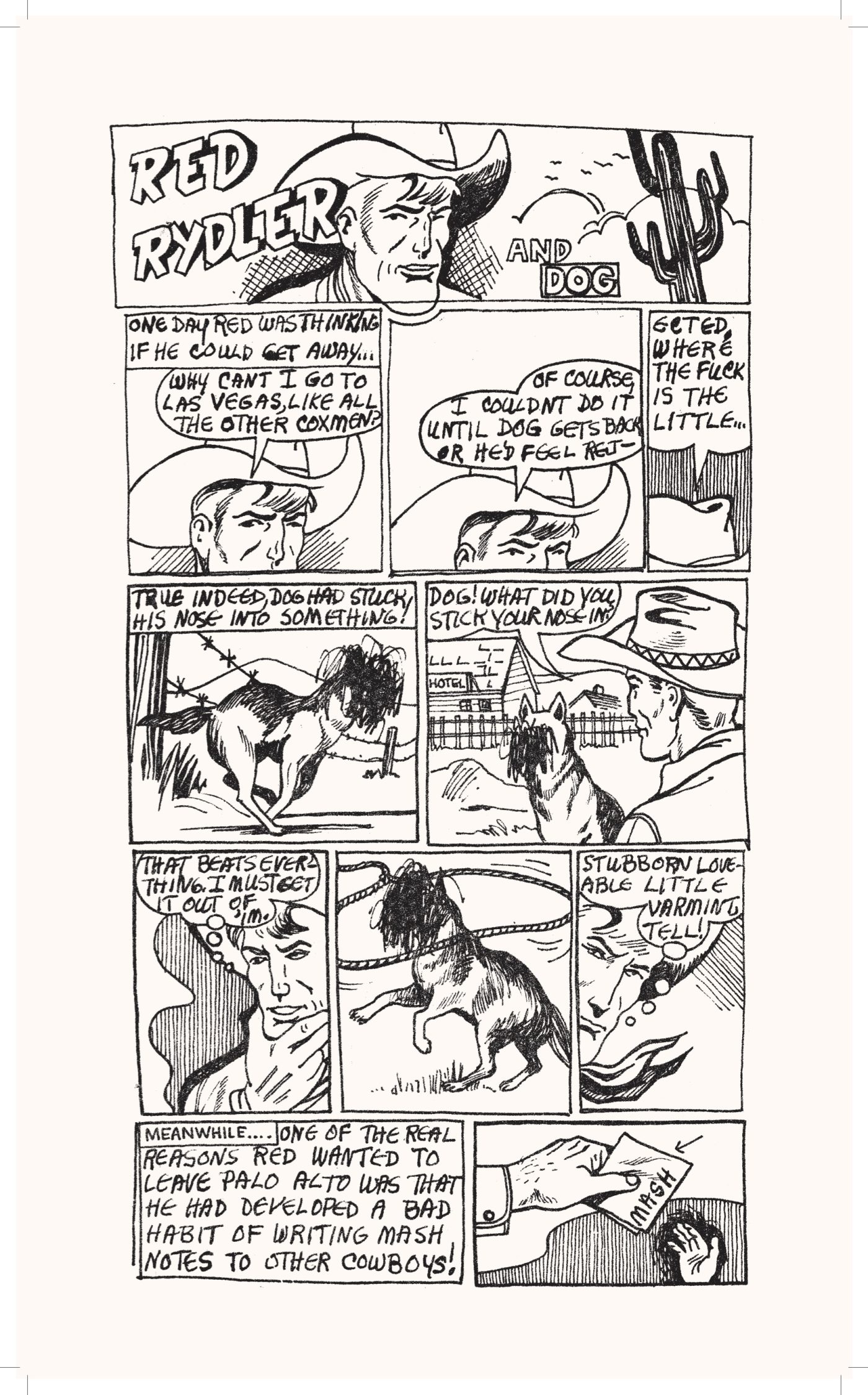

In the two-page strip “Red Rydler and Dog,” based on the primitive Western comic strip by Fred Harman, racism, gay longing and toxic masculinity do an uproarious dance. Brainard’s drawings capture the frank essence of generic graphic art while poet Frank O’Hara charges each speech balloon and caption with provocative thoughts and dialogue. It’s the essence of funny-sad with a chocolatey coating of absurdity, done with deadpan as if nothing’s awry. If this strip wins you over, you are C Comics material.

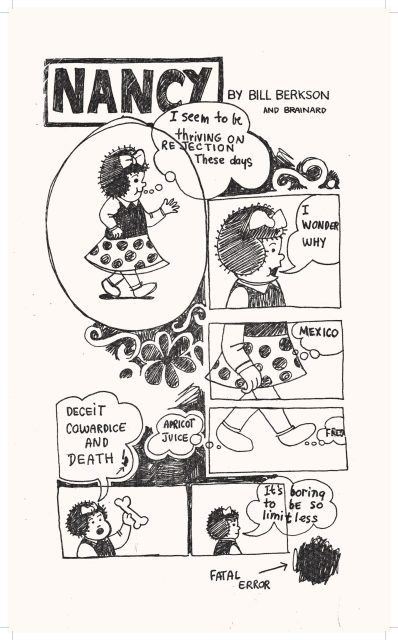

Brainard’s fondness for Nancy continues through C’s two issues. As Mark Newgarden and Bill Griffith would later understand, Brainard saw Bushmiller’s iconic character as a divine conduit of the ugly, off-putting and harsh ways of the world. A “Nancy” collaboration with Bill Berkson begins with a deformed-looking Nancy who thinks, "I seem to be thriving on rejection these days." The strip ends with her declaration, “It’s boring to be so limitless.” This dada one-pager is among the highlights of the first issue of C Comics.

Brainard’s fondness for Nancy continues through C’s two issues. As Mark Newgarden and Bill Griffith would later understand, Brainard saw Bushmiller’s iconic character as a divine conduit of the ugly, off-putting and harsh ways of the world. A “Nancy” collaboration with Bill Berkson begins with a deformed-looking Nancy who thinks, "I seem to be thriving on rejection these days." The strip ends with her declaration, “It’s boring to be so limitless.” This dada one-pager is among the highlights of the first issue of C Comics.

Most of the strips in these two issues are stand-alone experiments. “Skree,” in issue one, plays with the devices of sound effects, comics panels and captions and random imagery. Its final page is a thing of inspirational delight. “Food and Things,” a one-page collaboration with Gerland Malanga, confronts the reader with a spray of abstract and familiar images distributed on the page with playful elegance.

The first issue has the excitement of first love as Brainard and his collaborators experiment and dig deep into their shared subconscious. The difference between this work and the more high-profile Pop Art is noted by Kartalopoulos: Brainard suggests the shells of familiar figures, characters and settings. He leaves much to the reader’s consciousness to complete. One sees appropriated figures from comic books, as in the brilliant “What to Do?”, a collab with James Schulyer that suggests a berserk Edward Albee in its suburban, gender-bending menage a trois scenario, bolstered with Brainard’s repeated imagery.

The longer second issue delivers on the first’s promises. Mimeo murk becomes clean, sharp offset. Brainard’s artwork takes greater risks, and its 112 pages are a deeper dive into the witty, fragmented and reflective mindset of all its creators. Brainard’s imagery becomes more suggestive (in both senses of the word: it gives a rough essence of what it depicts and it goes further into sexual material). The results suggest that it might be considered the first great underground comic book.

I love the loose, reckless feeling of Brainard’s art. He draws freehand and his figures often distort as a result. A few fudged drawings are scritched into oblivion; others achieve a tentative, airy vibe that is fascinating for what it doesn’t contain. The 12-page strip “The Nancy Book,” by Padgett and Brainard, breaks a traditional comics narrative into a million slivers; the reader admires the rubble as they take a cautious stroll through it all. Its splash page, with a supe-hero drawing aborted and scribbled out, defies all principles of professional style. The seventh page, with a proud, striding Nancy who proclaims: “It freaks the atmosphere of my glands” (no period) is the best page of comics art I’ve seen this year.

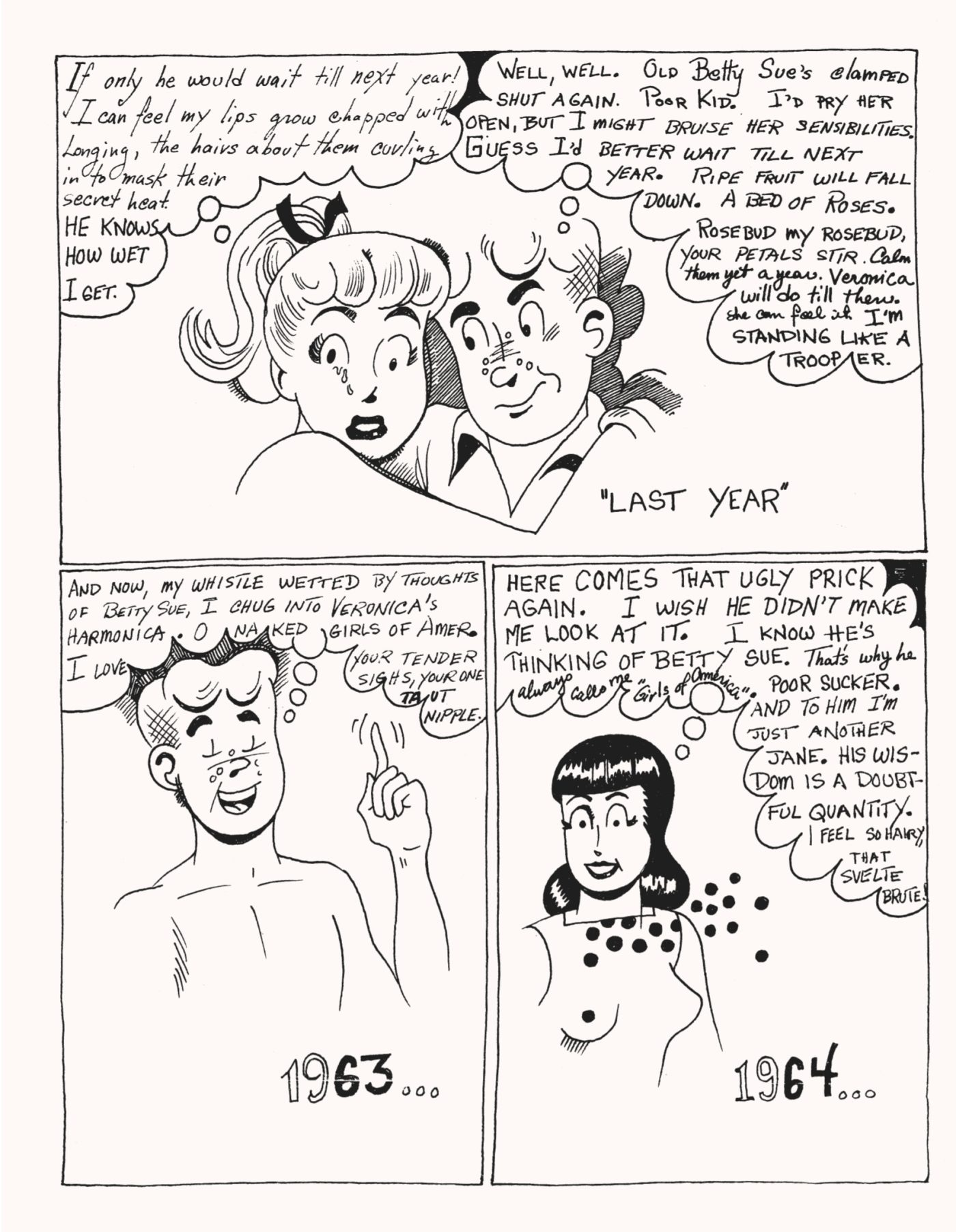

The adolescent cast of the Archie comics universe is pilfered in the confrontational “Betty Sue’s Biplane,” a collaboration with Dick Gallup that lays bare the erotic subtext of these wholesome teen comic books. It’s a seedy experience, with Brainard’s suggestive imagery (which uses open space as a virtue) and blurring of other comic-book genres into a heated evocation of male sexual arousal. Unlike Crumb’s sexually explicit work, this has an anthropologic detachment that makes its characters’ horniness a parody of desire — something to view with caution and concern rather than excitement.

A brilliant conceptual piece, “Pay Dirt” (words by Kenward Emlslie) is a conversation of stylized footwear that achieves a graphic and verbal beauty, panel by panel, page by page. This and the issue’s final story are masterpieces of Brainard’s visual conception and execution.

“People of the World: Relax!” is a solo Brainard work loaded with citations of the familiar (a deformed head of Dick Tracy; the Trix cereal rabbit; Dennis the Menace and, of course, Nancy) and a still-powerful message to all who read it. “This is a good life … sit down in the grass. It will not hurt you … do not kill ants. They are your best friends,” Brainard states with sincerity.

This is eccentric, assured, elastic and inspiring work — vital reading for anyone who longs for comics to break out of their ruts and run screaming through the fields. As such, The Complete C Comics is a major addition to the comics canon and an ideal gift for the non-conformist(s) in your life.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·