Magic, as it appears in fairy tales, is something we recognize but cannot analyze.

Why Cinderella must leave the ball at the stroke of midnight is not known. It is only known that this is the price named for the privilege of going to the ball adorned in gown and glass slippers.

Likewise is the reason why, in Darby O Gill and the Little People, a man may demand the captured Leprechaun grant three wishes, great wishes or small, but to ask a fourth wish is to lose them all.

Keep in mind, fairy tales differ from modern fantasy stories and from science fiction.

Magic as it appears in modern fantasy stories, as often as not, lacks this elusive and numinous quality. This is particularly true of tales following the spirit of Dungeons and Dragons by Gygax, where the magic is merely an alternate technology, used mostly as artillery of fireballs or lightning bolts, or, in Harry Potter, where the gift of levitation is used for an aerial form of rugby riding broomsticks.

In such stories, magic can be analyzed, and, for better or worse, it has lost its savor as magic.

In science fiction stories particularly, telepathy, teleportation, telekinesis are surely wondrous, but this is worldly wonder. The limitations the writer put on them are usually technical, not magical: a limit of range, or an inability to penetrate lead, not that they do not work in churchyards, or fail when the moon is full. Parapsychology is the paradox of unmagical magic.

So in science fiction stories, the disenchantment is complete: the wonder of technology, the wizardry of Jules Verne machines that fly and swim or H.G. Wells machines that reach the moon or travel in time, remains in full force (and this sense of wonder is indeed the sole point and virtue of science fiction).

But the point of the paradox of science fiction is to show natural settings and events of far worlds or future days — such as a visit to AD 802,701 — with the supernatural grandeur or horror of fairy tale — as when the Eloi are kept and herded by cannibal troglodyte Morlocks: these creatures have the glamor of elves and gnomes, made eerie by their separation from us across the gulf of eight thousand centuries.

Having said that, keep in mind that magic and wonder, even the grandeur of myth, may crop up in unexpected places in science fiction and space fantasy stories.

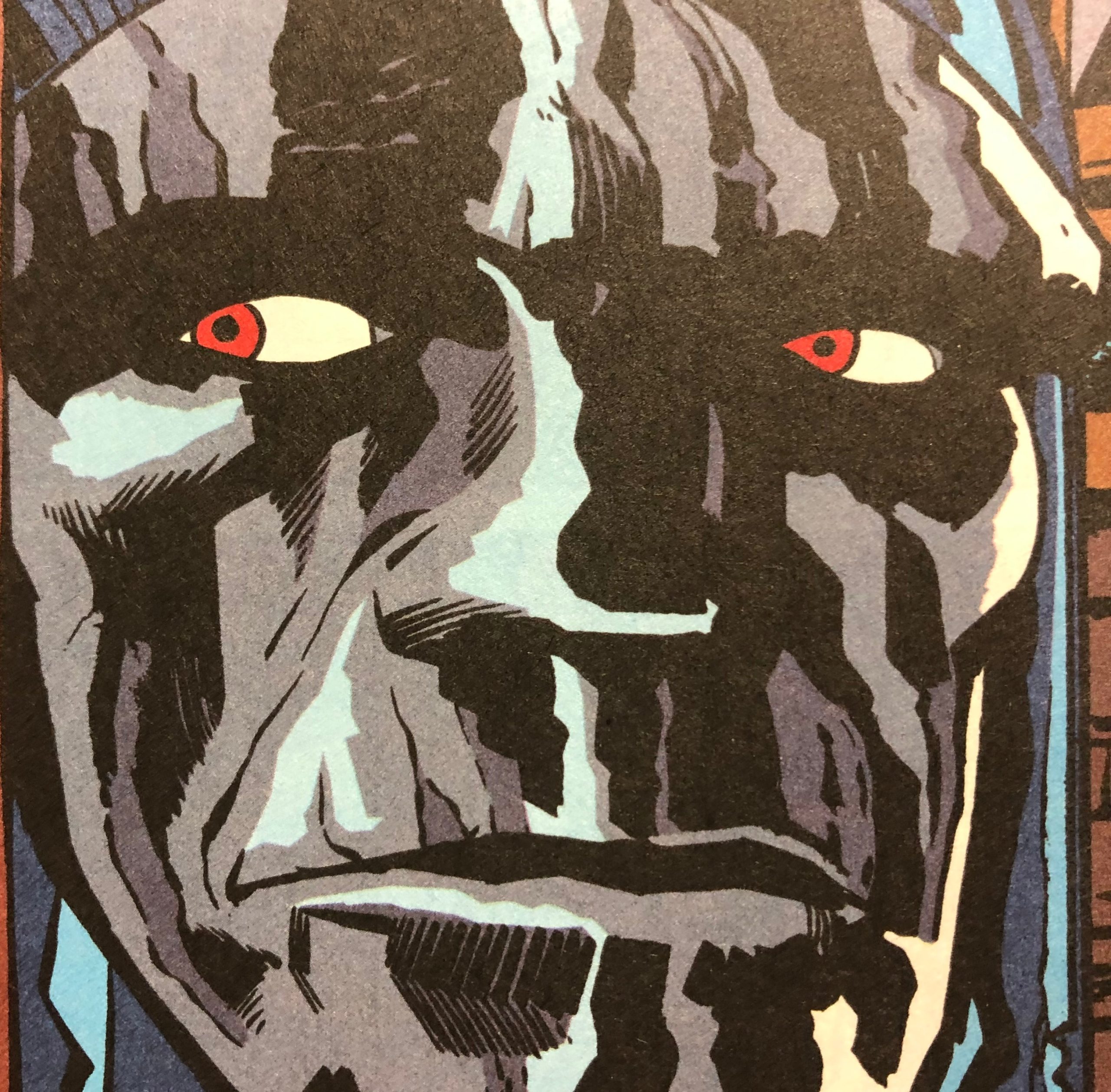

The mere whisper of the name of the dread and dreaded homeworld of the Shadows from BAYBLON FIVE, for example is Z’ha’dum — a name to conjure with!

And likewise, the grim character of the cyclops in the space fantasy KRULL is explained by the shameful confession that the race once had two eyes, but they bargained with the Beast of the Black Fortress. The Beast granted them the ability to see the future in return for the loss of one eye. But the Beast cheated them, so that the only thing they could see in the future was the day and hour of their own death.

This has all the grandness, grimness, and strangeness of fairy tale. Never make a bargain with The Beast!

In science fiction, it is perfectly in keeping that Sleeping Beauty could be wakened from her sleep by Dr. McCoy doing something clever with the transporter machine to reconstruct her body. But in a fairy tale, only true love’s first kiss breaks the spell, and nothing else will do.

So it may be otherwise in Science Fiction or modern Fantasy, but in fairy tales, the rule is simply the rule.

Fairy tales are artifacts of something more primal in man than the mere appetite for flights of fancy or speculations about other worlds and eons.

Children do not know the reason for the rules they are given, and, indeed, sometimes the adults do not know either, the thing having been proved by long custom to have its own weight and dignity merely by being customary.

Historian Elting E. Morison tells of a time when, during the Second World War, an antique field gun dating from the Boer War was put back in commission. The old gun had originally been on a horse drawn cart, but now was pulled by a jeep or truck. By custom, the five man gunnery team ran through its choreographed motions with speed and efficiency, each man doing his part, but that, when the gun was ready to fire, two would stand at attention. Asked why, they soldiers replied that this was as they had been trained. It was not until a veteran of the Boer War was asked that the answer emerged: those two men originally had been stationed there to hold the horse during the moment of firing to prevent them from bolting.

Sadly, we live in an age so enamored of progress and evolution that customs of long standing whose purpose has been forgotten are assumed either to be anachronism (as when gun-cart horses are replaced by jeeps, but the soldiers stand by nonetheless) or assumed to have had a hidden sinister purpose (as when marriage is dismissed as an oppression of the patriarchy, or private property dismissed as an oppression of the capitalist.)

Let us quote at length from G.K. Chesterton, from his 1929 book The Thing:

“In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

“This paradox rests on the most elementary common sense. The gate or fence did not grow there. It was not set up by somnambulists who built it in their sleep. It is highly improbable that it was put there by escaped lunatics who were for some reason loose in the street. Some person had some reason for thinking it would be a good thing for somebody. And until we know what the reason was, we really cannot judge whether the reason was reasonable.

“It is extremely probable that we have overlooked some whole aspect of the question, if something set up by human beings like ourselves seems to be entirely meaningless and mysterious.

“There are reformers who get over this difficulty by assuming that all their fathers were fools; but if that be so, we can only say that folly appears to be a hereditary disease.”

Fairy stories, in addition to all others benefits and wonders, rebuke the arrogance of men who think they know so well how the world works that they need not heed the rules of fairy godmothers or leprechaun kings about overstaying the ball or wishing too greedily for more wishes.

Fairy tale magic is a child-sized version of a miracle, a glimpse of grace into the greater world. Something numinous has been communicated, but its meaning eludes us.

For, like miracles, fairy tale magic comes from somewhere and points to something, and has a meaning, meant to do good to the good-hearted and visit evil to the evil-hearted, even as the curses of witches and evil fairies mean the opposite.

But, at times, the elfish glamor of the perilous realm that lurks beyond the edges of our maps, or in the abyss of outer space merely evokes wonder and strangeness, to remind mortal men that not all aspects of creation were meant for him. Those things were never given names by Adam, and may not have even been meant to be under the dominion of man. Adam named the beasts and birds and fish, after all, but not the stars and planets.

Originally posted here

English (US) ·

English (US) ·